Principles of Groundwater Flow | Engineering Hydrology - Civil Engineering (CE) PDF Download

Introduction

In the earlier lesson, qualitative assessment of subsurface water whether in the unsaturated or in the saturated ground was made. Movement of water stored in the saturated soil or fractured bed rock, also called aquifer, was seen to depend upon the hydraulic gradient. Other relationships between the water storage and the portion of that which can be withdrawn from an aquifer were also discussed. In this lesson, we derive the mathematical description of saturated ground water flow and its exact and approximate relations to the hydraulic gradient.

Continuity equation and Darcy’s law under steady state conditions

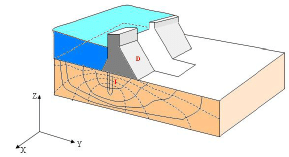

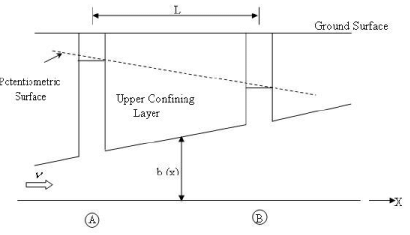

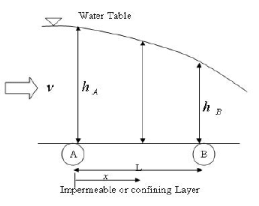

Consider the flow of ground water taking place within a small cube (of lengths ∆x, ∆y and ∆z respectively the direction of the three areas which may also be called the elementary control volume) of a saturated aquifer as shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Infinitesimal cube for deriving the equation of continuity of flow of ground water

It is assumed that the density of water (ρ) does not change in space along the three directions which implies that water is considered incompressible. The velocity components in the x, y and z directions have been denoted as νx, νy, νz respectively.

Since water has been considered incompressible, the total incoming water in the cuboidal volume should be equal to that going out. Defining inflows and outflows as:

Inflows:

In x-direction: ρ νx (∆y.∆x)

In y-direction: ρ νy (∆x.∆z)

In z-direction: ρ νz (∆x.∆y)

Outflows:

In X-direction:

In Y-direction:

In Z-direction:

The net mass flow per unit time through the cube works out to:

or

(2)

(2)

This is continuity equation for flow. But this water flow, as we learnt in the previous lesson, is due to a difference in potentiometric head per unit length in the direction of flow. A relation between the velocity and potentiometric gradient was first suggested by Henry Darcy, a French Engineer, in the mid nineteenth century. He found experimentally (see figure below) that the discharge ‘Q’ passing through a tube of cross sectional area ‘A’ filled with a porous material is proportional to the difference of the hydraulic head ‘h’ between the two end points and inversely proportional to the flow length’L’.

It may be noted that the total energy (also called head, h) at any point in the ground water flow per unit weight is given as

(3)

(3)

Where

Z is the elevation of the point above a chosen datum;

the pressure head, and

the pressure head, and

v2/2g is the velocity head

Since the ground water flow velocities are usually very small,v2/2g is neglected and  termed as the potentiometric head (or piezometric head in some texts)

termed as the potentiometric head (or piezometric head in some texts)

FIGURE 2. Flowthrough a saturated porous medium

Thus

(4)

(4)

Introducing proportionality constant K, the expression becomes

(5)

(5)

Since the hydraulic head decreases in the direction of flow, a corresponding differential equation would be written as

Q = -K.A. (dh/dI) (6)

The coefficient ‘K’ has dimensions of L/T, or velocity, and as seen in the last lesson this is termed as the hydraulic conductivity.

Thus the velocity of fluid flow would be:

(7)

(7)

It may be noted that this velocity is not quite the same as the velocity of water flowing through an open pipe. In an open pipe, the entire cross section of the pipe conveys water. On the other hand, if the pipe is filed with a porous material, say sand, then the water can only flow through the pores of the sand particles. Hence, the velocity obtained by the above expression is only an apparent velocity, with the actual velocity of the fluid particles through the voids of the porous material is many time more. But for our analysis of substituting the expression for velocity in the three directions x, y and z in the continuity relation, equation (2) and considering each velocity term to be proportional to the hydraulic gradient in the corresponding direction, one obtains the following relation

(8)

(8)

Here, the hydraulic conductivities in the three directions (Kx, Ky and Kz) have been assumed to be different as for a general anisotropic medium. Considering isotropic medium with a constant hydraulic conductivity in all directions, the continuity equation simplifies to the following expression:

(9)

(9)

In the above equation, it is assumed that the hydraulic head is not changing with time, that is, a steady state is prevailing.

If now it is assumed that the potentiometric head changes with time at the location of the control volume, then there would be a corresponding change in the porosity of the aquifer even if the fluid density is assumed to be unchanged.

What happens to the continuity relation is discussed in the next section.

Important term:

Porosity: It is ratio of volume of voids to the total volume of the soil and is generally expressed as percentage.

Ground water flow equations under unsteady state

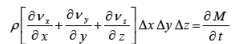

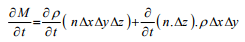

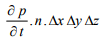

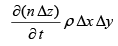

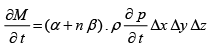

For an unsteady case, the rate of mass flow in the elementary control volume is given by:

(10)

(10)

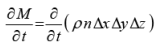

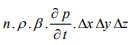

This is caused by a change in the hydraulic head with time plus the porosity of the media increasing accommodating more water. Denoting porosity by the term ‘n’, a change in mass ‘M’ of water contained with respect to time is given by

(11)

(11)

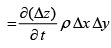

Considering no lateral strain, that is, no change in the plan area ∆x.∆y of the control volume, the above expression may be written as:

(12)

(12)

Where the density of water (ρ) is assumed to change with time. Its relation to a change in volume of the water Vw, contained within the void is given as:

(13)

(13)

The negative sign indicates that a reduction in volume would mean an increase in the density from the corresponding original values.

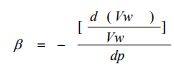

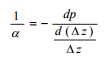

The compressibility of water, β, is defined as:

(14)

(14)

Where ‘dp’ is the change in the hydraulic head ‘p’ Thus,

(15)

(15)

That is,

dρ =ρ dp β (16)

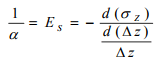

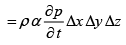

The compressibility of the soil matrix, α, is defined as the inverse of ES, the elasticity of the soil matrix. Hence

(17)

(17)

Where σZ is the stress in the grains of the soil matrix.

Now, the pressure of the fluid in the voids, p, and the stress on the solid particles, σZ, must combine to support the total mass lying vertically above the elementary volume. Thus,

p+σz= constant (18)

Leading to

dσz = -dp (19)

(20)

(20)

Also since the potentiometric head ‘h’ given by

(21)

(21)

Where Z is the elevation of the cube considered above a datum. We may therefore rewrite the above as

(22)

(22)

First term for the change in mass ‘M’ of the water contained in the elementary volume, Equation 12, is

(23)

(23)

This may be written, based on the derivations shown earlier, as equal to

(24)

(24)

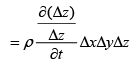

Also the volume of soil grains, VS, is given as

VS = (1-n) Δx Δy Δz (25)

Thus, dVS = [ d (∆ z) – d ( n ∆ z) ] ∆ x ∆ y (26)

Considering the compressibility of the soil grains to be nominal compared to that of the water or the change in the porosity, we may assume dVS to be equal to zero. Hence,

[ d (∆ z) – d ( n ∆ z) ] ∆ x ∆ y = 0 (27)

Or,

d (∆ z) = d ( n ∆ z) (28)

Which may substituted in second term of the expression for change in mass, M, of the elementary volume, changing it to

(29)

(29)

Thus, the equation for change of mass, M, of the elementary cubic volume becomes

(30)

(30)

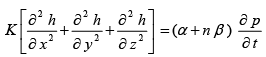

Combining Equation (30) with the continuity expression for mass within the volume, equation (10), gives the following relation:

(31)

(31)

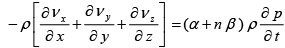

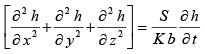

Assuming isotropic media, that is, KX=K=YKZ=K and applying Darcy’s law for the velocities in the three directions, the above equation simplifies to

(32)

(32)

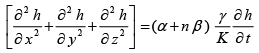

Now, since the potentiometric (or hydraulic) head h is given as

(33)

(33)

The flow equation can be expressed as

(34)

(34)

The above equation is the general expression for the flow in three dimensions for an isotropic homogeneous porous medium. The expression was derived on the basis of an elementary control volume which may be a part of an unconfined or a confined aquifer. The next section looks into the simplifications for each type of aquifer.

Ground water flow expressions for ground water flow unconfined and confined aquifers

Unsteady flow takes place in an unconfined and confined aquifer would be either due to:

- Change in hydraulic head (for unconfined aquifer) or potentiometric head (for confined aquifer) with time.

- And, or compressibility of the mineral grains of the soil matrix forming the aquifer

- And, or compressibility of the water stored in the voids within the soil matrix

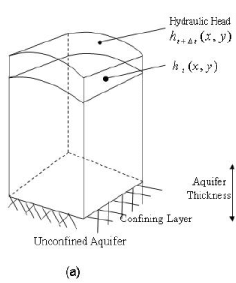

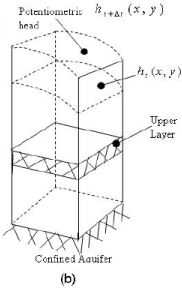

We may visually express the above conditions as shown in Figure 3, assuming an increase in the hydraulic (or potentiometric head) and a compression of soil matrix and pore water to accommodate more water

FIGURE 3. (a) Free surface of ground water table in unconfined aquifer (b) Potentiometric surface in confined aquifer

Since storability S of a confined aquifer was defined as

S = bγ (α + n β) (35)

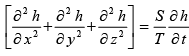

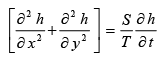

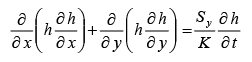

The flow equation for a confined aquifer would simplify to the following:

(36)

(36)

Defining the transmissivity T of a confined aquifer as a product of the hydraulic conductivity K and the saturated thickness of the aquifer, b, which is:

T = K•b (37)

The flow equation further reduces to the following for a confined aquifer

(38)

(38)

For unconfined aquifers, the storability S is given by the following expression

S = Sy + h Ss (39)

Where Sy is the specific yield and Ss is the specific storage equal to γ (α + n β )

Usually, Ss is much smaller in magnitude than Sy and may be neglected. Hence S under water table conditions for all practical purposes may be taken equal to Sy.

Two dimensional flow in aquifers

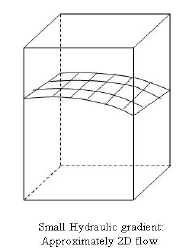

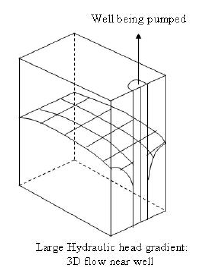

Under many situations, the water table variation (for unconfined flow) in areal extent is not much, which means that there the ground water flow does not have much of a vertical velocity component. Hence, a two – dimensional flow situation may be approximated for these cases. On the other hand, where there is a large variation in the water table under certain situation, a three dimensional velocity field would be the correct representation as there would be significant component of flow in the vertical direction apart from that in the horizontal directions. This difference is shown in the illustrations given in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4. Difference between small and large hydraulic gradients of ground water table

In case of two dimensional flow, the equation flow for both unconfined and confined aquifers may be written as,

(40)

(40)

There is one point to be noted for unconfined aquifers for hydraulic head ( or water table) variations with time. It is that the change in the saturated thickness of the aquifer with time also changes the transmissivity, T, which is a product of hydraulic conductivity K and the saturated thickness h. The general form of the flow equation for two dimensional unconfined flow is known as the Boussinesq equation and is given as

(41)

(41)

Where Sy is the specific yield.

If the drawdown in the unconfined aquifer is very small compared to the saturated thickness, the variable thickness of the saturated zone, h, can be replaced by an average thickness, b, which is assumed to be constant over the aquifer.

For confined aquifer under an unsteady condition though the potentiometric surface declines, the saturated thickness of the aquifer remains constant with time and is equal to an average value ‘b’. Solving the ground water flow equations for flow in aquifers require the help of numerical techniques, except for very simple cases.

Two dimensional seepage flow

In the last section, examples of two dimensional flow were given for aquifers, considering the flow to be occurring, in general, in a horizontal plane. Another example of two dimensional flow would that be when the flow can be approximated. to be taking place in the vertical plane. Such situations might occur as for the seepage taking place below a dam as shown in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5. Seepage flow below a concrete gravity dam

Under steady state conditions, the general equation of flow, considering an isotropic porous medium would be

(42)

(42)

However, solving the above Equation (42) for would require advanced analytical methods or numerical techniques. More about seepage flow would be discussed in the later session.

Steady one dimensional flow in aquifers

Some simplified cases of ground water flow, usually in the vertical plane, can be approximated by one dimensional equation which can then be solved analytically. We consider the confined and unconfined aquifers separately, in the following sections.

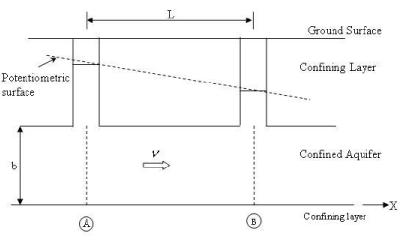

Confined aquifers

If there is a steady movement of ground water in a confined aquifer, there will be a gradient or slope to the potentiometric surface of the aquifer. The gradient, again, would be decreasing in the direction of flow. For flow of this type, Darcy’s law may be used directly.

Aquifer with constant thickness

This situation may be shown as in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6. Flowthrough an aquifer of constant thckness

Assuming unit thickness in the direction perpendicular to the plane of the paper, the flow rate ‘q’ (per unit width) would be expressed for an aquifer of thickness’b’

q = b *1 * v (43)

According to Darcy’s law, the velocity ‘v’ is given by

(44)

(44)

Where h, the potentiometric head, is measured above a convenient datum. Note that the actual value of ’h’ is not required, but only its gradient  in the directionof flow, x, is what matters. Here is K is the hydraulic conductivity

in the directionof flow, x, is what matters. Here is K is the hydraulic conductivity

Hence,

(45)

(45)

The partial derivative of ‘h’ with respect to ‘x’ may be written as normal derivative since we are assuming no variation of ‘h’ in the direction normal to the paper. Thus

(46)

(46)

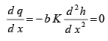

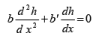

For steady flow, q should not vary with time, t, or spatial coordinate, x. hence,

(47)

(47)

Since the width, b, and hydraulic conductivity, K, of the aquifer are assumed to be constants, the above equation simplifies to:

d2h/dx2 =0 (48)

Which may be analytically solved as

h = C1 x + C2 (49)

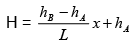

Selecting the origin of coordinate x at the location of well A (as shown in Figure 6), and having a hydraulic head,hA and also assuming a hydraulic head of well B, located at a distance L from well A in the x-direction and having a hydraulic head hB, we have:

hA = C1.0+C2 and

hB = C1.L+C2

Giving

C1 = h - hA /L and C2= hA (50)

Thus the analytical solution for the hydraulic head ‘h’ becomes:

(51)

(51)

Aquifer with variable thickness

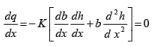

Consider a situation of one- dimensional flow in a confined aquifer whose thickness, b, varies in the direction of flow, x, in a linear fashion as shown in Figure 7.

FIGURE 7. Flowthrough an aquifer with variable thickness

The unit discharge, q, is now given as

q = - b (x) K dh/dx (52)

Where K is the hydraulic conductivity and dh/dx is the gradient of the potentiometric surface in the direction of flow,x.

For steady flow, we have,

(53)

(53)

Which may be simplified, denoting db/dx as b'

(54)

(54)

A solution of the above differential equation may be found out which may be substituted for known values of the potentiometric heads hA and hB in the two observation wells A and B respectively in order to find out the constants of integration.

Unconfined aquifers

In an unconfined aquifer, the saturated flow thickness, h is the same as the hydraulic head at any location, as seen from Figure 8:

FIGURE 8. Flowthrough an unconfined aquifer

Considering no recharge of water from top, the flow takes place in the direction of fall of the hydraulic head, h, which is a function of the coordinate, x taken in the flow direction. The flow velocity, v, would be lesser at location A and higher at B since the saturated flow thickness decreases. Hence v is also a function of x and increases in the direction of flow. Since, v, according to Darcy’s law is shown to be

(55)

(55)

the gradient of potentiometric surface, dh/dx, would (in proportion to the velocities) be smaller at location A and steeper at location B. Hence the gradient of water table in unconfined flow is not constant, it increases in the direction of flow.

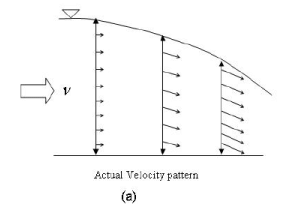

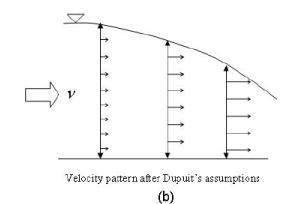

This problem was solved by J.Dupuit, a French hydraulician, and published in 1863 and his assumptions for a flow in an unconfined aquifer is used to approximate the flow situation called Dupuit flow. The assumptions made by Dupuit are:

- The hydraulic gradient is equal to the slope of the water table, and

- For small water table gradients, the flow-lines are horizontal and the equipotential lines are vertical.

The second assumption is illustrated in Figure 9.

FIGURE 9. (a) Actual velocity pattern in ground water flow and

(b) Assumption of Dupuit regarding ground water flow

Solutions based on the Dupuit’s assumptions have proved to be very useful in many practical purposes. However, the Dupuit assumption do not allow for a seepage face above an outflow side.

An analytical solution to the flow would be obtained by using the Darcy equation to express the velocity, v, at any point, x, with a corresponding hydraulic gradient dh/dx, as

(56)

(56)

Thus, the unit discharge, q, is calculated to be

(57)

(57)

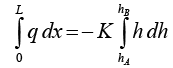

Considering the origin of the coordinate x at location A where the hydraulic head us hA and knowing the hydraulic head hB at a location B, situated at a distance L from A, we may integrate the above differential equation as:

(58)

(58)

Which, on integration, leads to

(59)

(59)

Or,

(60)

(60)

Rearrangement of above terms leads to, what is known as the Dupuit equation:

(61)

(61)

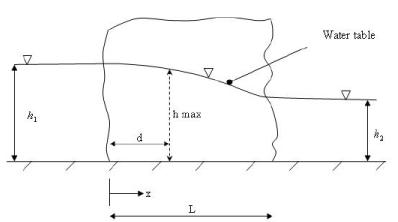

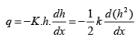

An example of the application of the above equation may be for the ground water flow in a strip of land located between two water bodies with different water surface elevations, as in Figure 10.

FIGURE 10. Ground water flow through a strip of land with difference in water surface elevation on either side.

The equation for the water table, also called the phreatic surface may be derived from Equation (61) as follows:

(62)

(62)

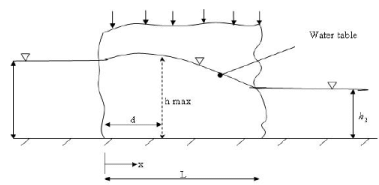

In case of recharge due to a constant infiltration of water from above the water table rises to a many as shown in Figure 11:

FIGURE 11. Ground water flow through a strip of land with infiltration from above

There is a difference with the earlier cases, as the flow per unit width, q, would be increasing in the direction of flow due to addition of water from above. The flow may be analysed by considering a small portion of flow domain as shown in Figure 12.

FIGURE 12. Definition of terms for flow analysis for the case shown in Figure 11

Considering the infiltration of water from above at a rate i per unit length in the direction of ground water flow, the change in unit discharge dq is seen to be

dq = i .dx (63)

Or,

dq / dx = i (64)

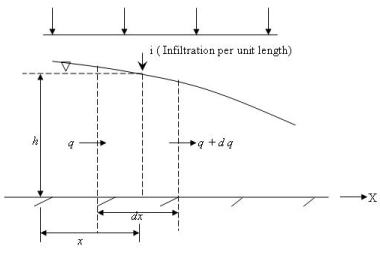

From Darcy’s law,

(65)

(65)

(66)

(66)

Substituting the expression for dq/dx, we have,

(67)

(67)

Or,

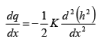

(68)

(68)

The solution for this equation is of the form

Kh2 + 2x2 = C1 x + C2 (69)

If, now, the boundary condition is applied as,

At x = 0, h = h1, and

At x = L, h = h2

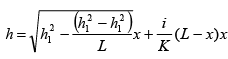

The equation for the water table would be:

(70)

(70)

And,

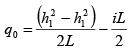

q x = q0 + 2x (71)

Where q0 is the unit discharge at the left boundary, x = 0, and may be found out to be

(72)

(72)

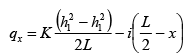

Which gives an expression for unit discharge qx at any point x from the origin as

(73)

(73)

For no recharge due to infiltration, i = 0 and the expression for qx is then seen to become independent of x, hence constant, which is expected.

|

20 videos|36 docs|30 tests

|

FAQs on Principles of Groundwater Flow - Engineering Hydrology - Civil Engineering (CE)

| 1. What are the principles of groundwater flow in civil engineering? |  |

| 2. How does Darcy's law relate to groundwater flow in civil engineering? |  |

| 3. What is hydraulic conductivity and why is it important in groundwater flow analysis? |  |

| 4. How is groundwater flow direction determined in civil engineering? |  |

| 5. What factors influence the rate of groundwater flow in civil engineering projects? |  |

|

Explore Courses for Civil Engineering (CE) exam

|

|