The Indian Evidence Act - 1 | Civil Law for Judiciary Exams PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Theory of Relevancy Under the Indian Evidence Act |

|

| The Concept of Burden of Proof |

|

| Presumptions in the Indian Evidence Act |

|

| Best Evidence Rule : An Overview |

|

Theory of Relevancy Under the Indian Evidence Act

Relevancy in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

- Definition: Relevancy is defined in Section 3 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. A fact is considered relevant to another when it is connected to it in any way specified by the Act.

- Relevant Fact: The concept of relevancy pertains to facts that support or prove another fact. These are not issues on their own but serve as the basis for inferring facts in question.

- Differentiation: Relevancy is different from admissibility. Relevancy is based on logic and probability, while admissibility is determined by law. Relevancy assesses whether facts are pertinent to the issue, whereas admissibility determines if evidence can be accepted.

- Thayer's View: Thayer believed that relevancy is a logical concept. He argued that irrelevant evidence should be excluded without exception, and relevant evidence should meet all necessary legal tests.

- Stephen's Perspective: Stephen's concept of legal relevancy equates the relevancy of facts with their legal admissibility. He suggested that the relevancy of evidence either increases or decreases the likelihood of the fact in question's existence.

Scope and Applicability:

- Sections 3 and 5 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 define relevancy. Chapter II of the Act deals with the relevancy of facts.

- Sections 6-11 outline various situations where relevancy applies. Sections 12-55 provide specific instances of relevant facts and procedures for making previously irrelevant facts relevant under Section 11.

- Section 13 addresses relevancy in cases involving customs or rights. Section 16 relates to the relevance of the course of business.

Literature Review:

- Ratanlal and Dhirajlal's Law of Evidence: Helped in understanding concepts like relevancy, admissibility, and probative value.

- Hock Lai's Article: Clarified the difference between legal and logical relevancy and discussed evidence weight.

- SC Sarkar's Law of Evidence: Provided updated case law and analysis of court decisions in India.

Research Questions:

- Is there a conflict between logical and legal relevancy?

- Has the theory of relevancy evolved in Indian case law?

Hypothesis:

- Relevant and admissible facts are distinct. All admissible evidence is relevant, but not all relevant facts are admissible.

Research Focus:

- Examine the difference between logical and legal relevancy.

- Explore the concept of relevancy in Indian evidence law.

Research Methodology:

- Doctrinal method used to research various articles and cases on relevancy.

- Aim to explore underlying issues of relevancy and court interpretations over time.

Logical Relevancy vs. Legal Relevancy:

- Probativeness: Evidence must increase or decrease the probability of a fact's existence, either actually or measurably.

- Materiality: The issue in dispute between parties.

- Both components together make a fact relevant.

- Lawyers must convince judges of relevancy using common sense.

- Section 5 to Section 55: These sections in the Indian Evidence Act deal with the relevancy of facts.

- Distinction: Logical relevancy and legal relevancy are not synonymous. A fact can be logically relevant but not legally admissible, as in the case of conversations between spouses.

- Res Gestae: Principle under Section 6 referring to a transaction or thing done. Sections 6 to 16 provide facts directly linked to the issue, like cause and effect, motive.

- Confessions: Covered under Section 17 to Section 31. Sections 40 to 44 discuss the relevance of court judgments. Sections 45 to 51 address third-party opinions. Sections 52 to 55 relate to the character of a person.

Legal Relevancy:

- Legal relevancy is crucial for deciding the admissibility of facts in court.

- It is a legal question, not based on logic.

- A fact must meet legal criteria to be admissible, even if it is not logical.

- If a fact is both logically and legally relevant, the circumstances of its recovery become irrelevant.

- Legal relevancy has a higher evidentiary threshold and is inclusive of logical relevancy.

- Legal admissibility, as per Professor J.H. Wigmore, lies between probative value and evidence reliability.

- Courts reject inadmissible evidence regardless of civil or criminal proceedings.

- Inadmissible evidence does not affect the relevance of illegally obtained evidence, but tampering is checked.

- Confessions before police officers are an example of the difference between logical relevancy and legal admissibility.

Relevancy Under Indian Evidence Act 1872

- The Indian Evidence Act, 1872 is a crucial piece of legislation that outlines the rules for admissibility and relevance of evidence in Indian courts.

- Understanding the concept of relevance under this Act is essential for legal professionals, as it determines what evidence can be considered by the court.

- In this article, we will explore the nuances of relevance as per the Indian Evidence Act, using simple language for better comprehension.

Relevance under the Indian Evidence Act

- Relevance acts as a link between a statement of proof and a statement that needs to be proved.

- The Indian Evidence Act does not provide a specific definition of relevance or relevant fact. Instead, it implies that one fact becomes applicable to another when there is a logical connection between them.

- Sections 6 to 55 of the Act outline the concept of relevancy. A fact is considered relevant if it is related to the fact in issue, even if it may not be admissible.

- The determination of relevancy is based on common sense, logic, practical experience, and basic knowledge of affairs.

- There are two essential components of relevance: nothing that isn't logically verified should be received, and everything that is probative or verified should be included unless explicitly excluded by law or policy.

- Relevancy is not solely dependent on law; it also relies on practical and human experience.

Sections of the Indian Evidence Act relating to Relevance

- Section 6: This section makes facts other than the facts in issue relevant if they are closely connected to the fact in issue and occur in the same transaction. It allows for the inclusion of hearsay evidence in certain circumstances, as seen in cases like Krishan Kumar Malik v. State of Haryana .

- Section 7: This section deals with evidence related to the occasion, cause, or effect of the fact in issue, including forensic evidence like fingerprints and footprints. It emphasizes the need for a close connection between the evidence and the fact in issue.

- Section 8: Section 8 includes evidence related to motive, preparation, and subsequent conduct. Motive is crucial for establishing the chain of events leading to the crime, but it cannot be the sole basis for conviction.

- Section 9: This section addresses facts that are relevant but require the introduction of another fact to prove their relevance or to rebut an already relevant fact.

- Section 10: Section 10 broadens the scope of relevance for actions or statements made by conspirators in furtherance of a common design. It allows for a wider interpretation compared to English law.

- Sections 17-21: These sections deal with admissions, which are broader than confessions. Confessions are specific acknowledgments of guilt, while admissions can be used in civil cases.

- Sections 24-30: These sections pertain to confessions and their admissibility. Confessions made before a police officer are generally not admissible unless they lead to relevant evidence.

- Sections 45-51: These sections allow the court to seek expert opinions on specific subjects. Expert opinions should be corroborative and not contradictory to other evidence in the case.

- Sections 52-55: These sections relate to character evidence. In civil cases, character evidence is not relevant unless it falls under certain exceptions. In criminal cases, evidence of good character is relevant, while evidence of bad character is subject to exceptions.

- Sections 34-39: These sections deal with statements made under special circumstances, such as statements made by deceased persons or persons unable to testify.

- Sections 40-44: These sections make court judgments and third-party opinions relevant in certain cases.

- Sections 52-55: These sections address character and reputation evidence. Evidence of good character is relevant in criminal cases, while evidence of bad character is subject to exceptions.

Conclusion

- Relevancy in the Indian Evidence Act is not inherent but varies from case to case.

- While legally relevant evidence is admissible, logically relevant evidence may not always be accepted.

- The Act uses "relevant" in a dual sense, meaning both admissibility and connection to the case.

- Understanding the nuances of relevancy is crucial for legal professionals to effectively present and challenge evidence in court.

The Concept of Burden of Proof

- The term "burden of proof" is not explicitly defined in the Indian Evidence Act.

- However, it essentially refers to the legal responsibility of parties to prove certain facts to help the court make a decision in their favor.

- The burden of proof outlines who is responsible for proving a fact in a legal case.

- This concept is detailed in Chapter VII of the Indian Evidence Act.

Sections on Burden of Proof

- Sections 101 to 103. These sections address the burden of proof in general cases.

- Sections 104 to 106. These sections specify situations where the burden of proof lies with a particular individual.

Onus Probandi and Factum Probans

- Onus Probandi. This principle means that the person making a positive assertion has to prove it. For example, if someone claims that a certain event happened, they have the onus probandi to provide evidence for it.

- Factum Probans. This concept involves the party trying to strengthen their case by proving a specific fact that they are assumed to be aware of.

Factum Probans and Factum Probandum

Burden of Proof in Criminal Trials

- In criminal trials, the prosecution carries the burden of proof, meaning they must prove the defendant's guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

- The accused is presumed innocent until proven guilty, following the fundamental principle of criminal law.

Role of Evidence

- Evidence is crucial in establishing the connection between the disputed fact (factum probandum) and the evidential fact (factum probans).

- The fact in dispute is hypothetical, while the evidential fact is presented as a reality to convince the court.

Legal Provisions and Case Laws

- Order 6, Rule 2 of the Civil Procedure Code, 1908: Pleadings should contain only essential facts in a concise manner.

- Indian Evidence Act: Sections 101 to 104 outline the burden of proof and its implications in legal proceedings.

- Case Laws: Various cases such as State of Rajasthan vs Sher Singh, Md. Allmuddin v. State of Assam, Jarnail Singh v. State of Punjab, and Ouseph v. State of Kerala highlight the principles of burden of proof and the responsibilities of prosecution and defense.

Section 105 of the Indian Evidence Act

Burden of Proof in Criminal Proceedings

- When a person is accused of a crime, it is their responsibility to prove the circumstances that justify their actions based on general exceptions in the Indian Penal Code (IPC) or other laws.

- Initially, it is up to the prosecution to prove the accused's guilt. Once they establish this, the burden shifts to the accused to demonstrate their defense using general exceptions.

- This principle, known as the reverse onus clause, is unique to criminal proceedings. It places the onus on the accused to be aware of all relevant incidents.

Section 106 of the Indian Evidence Act

Section 106 of the Indian Evidence Act:

- Concept of a Fair Trial: Section 106 aims to promote a fair trial by simplifying the process of establishing facts.

- Burden of Proof: It removes the burden of proving facts that are impossible and favors the accused.

- Challenge to Presumptions: The accused is given the opportunity to challenge presumptions of facts based on the sequence of events.

- Prosecution Exploitation: There are concerns that the prosecution may exploit this clause to evade its responsibility of establishing the legal burden.

Concept of Presumptions under the burden of proof

Presumptions in Law

- Presumptions are legal conclusions made by the court about the existence of certain facts.

- They are an exception to the rule that the party asserting a fact has the burden of proof.

- When certain facts are presumed to exist, the party benefiting from the presumption is relieved of the burden of proof.

Types of Presumptions

- Presumptions can be factual, legal, or mixed.

- Factual presumptions are based on the belief of certain facts.

- Legal presumptions are based on legal rules.

- Mixed presumptions involve both factual and legal elements.

Presumptions and Documentary Evidence

- When a certified copy of an original document is presented to the court, Section 79 of the Act presumes it to be a genuine copy.

- Section 85 of the Act allows the court to infer that a power of attorney is issued by a real authorized person.

Presumption of Innocence

- The presumption of innocence means that everyone is presumed innocent until proven guilty.

- Justice Thomas, in the case of State of West Bengal v. Mohd. Omar (2002), suggested a shift in perspective on this principle.

- He argued that placing the burden of evidence solely on the prosecution benefits only the accused in serious crimes and harms society.

- When the prosecution establishes certain facts, the court should infer their existence.

- Once the court is satisfied with the prosecution's case, the burden of proof shifts to the accused, who is the only one aware of all the details.

Conclusion:

- The Evidence Act of 1872 is a comprehensive law addressing the burden of proof.

- However, advancements in electronic evidence and the burden of proof require clearer judicial interpretation.

- Many cases in the criminal justice system have not resulted in convictions due to the traditional approach to the presumption of innocence and mental aspect requirements.

- It is important to ensure that any changes do not compromise the integrity and reputation of judges as impartial officials.

Presumptions in the Indian Evidence Act

Presumption in Law

- Definition: Presumption in law refers to the process of drawing conclusions about the existence of certain facts based on the available evidence and the circumstances of the case. It involves making inferences that can be either affirmative or negative.

- Process: Presumptions are made using the best probable reasoning from the circumstances presented. When a primary fact is established, it can be used to prove other related facts until they are disproved.

- Section 114 of the Indian Evidence Act: This section specifically addresses the court's ability to presume the existence of a fact that is likely to have occurred, taking into account the usual course of natural events, human conduct, and public and private business.

- Affirmative vs. Negative Presumptions: Affirmative presumptions support the existence of a fact, while negative presumptions suggest its non-existence.

- Importance: Presumptions play a crucial role in legal proceedings by allowing the court to draw reasonable conclusions based on the evidence and circumstances, thereby facilitating the determination of facts.

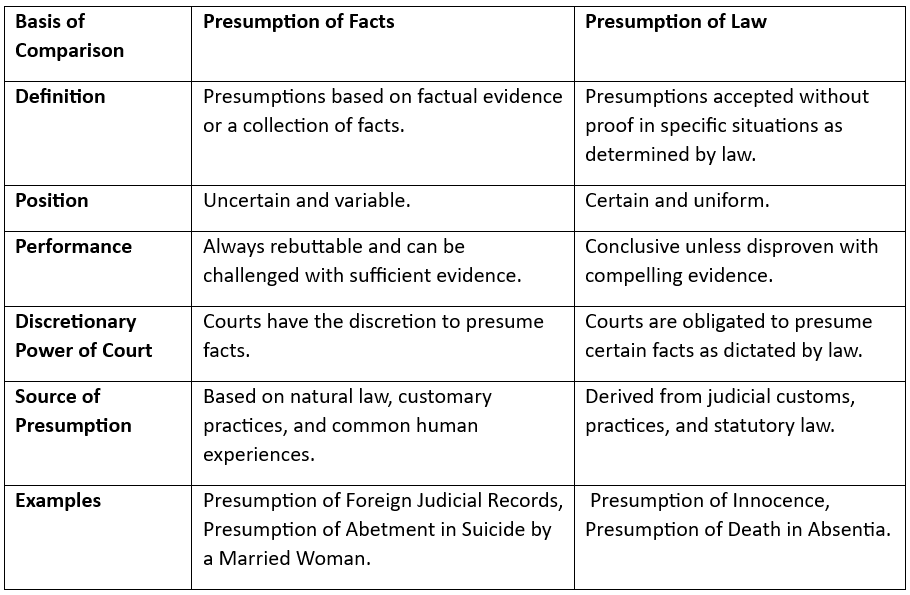

Difference between Presumption of Facts and Presumption of Law

Difference between May Presume Shall Presume and Conclusive proof

Presumptions in the Indian Evidence Act:

The Indian Evidence Act contains several sections that deal with the concept of presumptions. Presumptions are assumptions that the court makes based on certain facts or circumstances. There are three types of presumptions in the Indian Evidence Act: May Presume, Shall Presume, and Conclusive Presumptions/Proofs.

1. May Presume.

- Definition. May Presume refers to the court's discretionary power to assume certain facts as proved, while allowing the possibility of disproof or the need for corroborative evidence.

- Rebuttable Presumption. This concept deals with rebuttable presumption, meaning that the presumption can be challenged and disproved.

- Proved Facts. According to Section 4 of the Indian Evidence Act, a fact or group of facts may be considered proved until they are disproved.

- Discretionary Power. The court has the discretion to decide whether to accept the presumption or require further evidence to support it.

2. Shall Presume.

- Strong Assertion. Shall Presume indicates a strong assertion or intention to determine a fact as proved.

- No Discretionary Power. In cases of Shall Presume, the court does not have discretionary power. Instead, the court presumes facts or groups of facts as proved until they are disproved by the other party.

- Presumption of Law. Shall Presume is also known as Presumption of Law, Artificial Presumption, Obligatory Presumption, or Rebuttable Presumption of Law. It is a branch of jurisprudence.

3. Conclusive Presumptions/Proofs.

- Strongest Presumption. Conclusive Presumptions/Proofs represent one of the strongest presumptions that a court may assume. However, these presumptions are not solely based on logic but are believed to be for the welfare or upbringing of society.

- Absolute Power of Law. The law has absolute power in cases of Conclusive Proofs, and no evidence contrary to the presumption is allowed. This means that the presumed facts under Conclusive Proofs cannot be challenged, even with probative evidence.

- Irrebuttable Presumptions. Section 41, 112, and 113 of the Evidence Act, as well as Section 82 of the Indian Penal Code, are important provisions related to irrebuttable presumptions or Conclusive Presumptions.

Conclusive Proofs:

- Definition. Conclusive Proof refers to a situation where the establishment of one fact leads to the automatic acceptance of other facts or conditions as proved, as per the provisions of the Act.

- Burden of Proof. The court shall regard all other facts as proved only if the primary fact is proven beyond reasonable doubt.

- Prohibition of Contrary Evidence. Once the primary fact is established, no evidence contrary to the other facts presumed as conclusive proofs shall be allowed.

Illustration. Suppose A and B get married on June 1. A leaves for work shortly after the wedding and returns six months later, only to discover that B is pregnant. A files for divorce, claiming he is not responsible for damages to B or their illegitimate child, arguing that he never consummated the marriage. However, the court will conclusively presume that the child is legitimate because A was with B for at least one day after their marriage. This presumption cannot be challenged, even if A presents evidence to the contrary.

General Classification of Presumption

Presumption of Law:

- This type of presumption is based on legal principles and is applied by the court as a matter of law.

- For example, in certain cases, the law presumes that a person intends the natural consequences of their actions, such as in cases of negligence.

Presumption of Facts:

- This presumption is based on factual circumstances and is applied by the court based on the evidence presented.

- For example, if a person is found in possession of stolen goods shortly after a theft, the court may presume that they were involved in the theft.

Mixed Presumption:

- This category includes both aspects of law and fact.

- It is applied in cases where the court needs to consider both legal principles and factual circumstances to reach a conclusion.

- For example, in cases of marital disputes, the court may consider both legal provisions and the specific facts of the case to make a decision.

1) Presumption of Facts

Presumptions of facts refer to the inferences that are drawn naturally and reasonably based on observations and circumstances in the course of basic human conduct. These are also known as material or natural presumptions. Natural presumptions are instances of circumstantial evidence and are considered necessary to avoid ambiguity in the legal system. They are generally rebuttable in nature.

There are several provisions in the Indian Evidence Act that address natural presumptions, including Section 86-88, Section 90, Section 113A, and Section 113B. Section 113A and Section 113B are particularly important as they deal with presumptions related to abetment of suicide by a married woman and dowry death, respectively.

Section 113A deals with the presumption of abetment of suicide by a married woman within seven years of her marriage if she has been subjected to cruelty by her husband or his relatives as per Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC).

Section 113B deals with the presumption of dowry death if the woman has been subjected to cruelty or harassment for dowry demand by her husband or his relatives.

The concept of "shall presume" is used under presumptions of facts, which means that the court will consider certain facts as proven until they are disproved by the accused. This concept ensures that some facts are recognized as proven by making a mandatory presumption.

Conditions for Presumption of Facts

- Foreign Judicial Records (Section 86). The court can presume the originality and accuracy of certified copies of foreign judicial records if they are consistent with local rules. If not, these judgments lose evidentiary value.

- Abetment of Suicide by a Married Woman (Section 113A). The court can presume that a married woman's suicide was abetted by her husband or his relatives if certain conditions are met: (i) The suicide occurred within seven years of marriage, and (ii) The husband or his relative subjected her to cruelty as defined in Section 498A of the IPC.

- Abetment of Suicide for Dowry (Section 114B). This section allows the court to presume that a married woman's suicide was abetted by her husband and his relatives for dowry reasons if there is evidence of cruelty or harassment for dowry.

Case Examples

- Chhagan Singh v State of Madhya Pradesh. The court acquitted the accused under Section 113A because the essentials for presumption were not met.

- Nilakantha Pati v State of Orissa. The court found the presumption rebuttable and acquitted the accused based on relevant arguments.

- Mangal Ram & Anor v State of Madhya Pradesh. The court initially presumed the accused's responsibility under Section 113B, but later acquitted them when evidence of cruelty was disproven.

Key Distinctions Between Sections

- Section 113A. Focuses on abetment of suicide by a married woman within seven years of marriage due to cruelty.

- Section 114B. Concerns abetment of suicide for dowry, requiring proof of cruelty or harassment for dowry demand.

Concept of 'May Presume' (Section 114)

- The court may presume the existence of certain facts based on natural events, human conduct, and public or private business.

- Illustrations. Include presumptions related to negotiable instruments, ancestral property, refusal to answer questions, and possession of stolen goods.

2) Presumption of Law-

Presumptions of law are inferences and beliefs established or assumed by the law itself. These presumptions can be classified into two categories: rebuttable presumptions and irrebuttable presumptions.

Rebuttable Presumptions:

Rebuttable presumptions are considered strong evidence until proven otherwise. For example, if a person is found in possession of stolen property, it is reasonable to presume that they are either the thief or a receiver of stolen goods.

Matrimonial offenses are a common context for rebuttable presumptions, as evidence is often scarce due to the private nature of these crimes. The law recognizes several important provisions in such cases:

- Section 113A: Presumption of abetment of suicide by a married woman within seven years of marriage.

- Section 113B: Presumption of dowry death within seven years of marriage.

- Section 112: Birth during marriage as conclusive proof of legitimacy.

In the case of Shanti v. State of Haryana, the Supreme Court upheld the presumption of dowry death under Section 113B when a bride died under suspicious circumstances shortly after her in-laws restricted her contact with her parents and demanded additional dowry.

In State of M.P. v. Sk. Lallu, the court applied Section 113A presumption in a case where a newlywed wife was subjected to severe abuse by her in-laws and ultimately died from extensive burn injuries.

Irrebuttable Presumptions

Irrebuttable presumptions, also known as presumptio iuris et de iure, cannot be challenged by any additional evidence or argument. For instance, a child under the age of seven is presumed incapable of committing a crime.

Conditions for Presumption of Law:

Presumption of Innocence

- The presumption of innocence, as articulated in legal maxims like ei incumbit probatio qui dicit, non qui negat , places the burden of proof on the accuser rather than the accused. This principle ensures that individuals are considered innocent until proven guilty.

- In cases such as Chandra Shekhar v. State of Himachal Pradesh and Dataram Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh & anr., the courts emphasized the importance of individual freedom and the presumption of innocence as fundamental rights protected by the Constitution.

Birth During Marriage

- The Latin maxim pater est quem nuptiae demonstrant underlines the assumption that a husband is the father of a child born to his wife during their marriage. Section 112 of the Indian Evidence Act addresses the legitimacy of children born during a valid marriage, establishing it as conclusive proof of legitimacy.

- The presumption of legitimacy can only be challenged by proving non-access or that the marriage was not consummated. This legal principle aims to uphold public morality and prevent the questioning of a child's legitimacy.

- In the case of Revanasiddappa v. Mallikarjun, the Supreme Court highlighted the constitutional objectives of equality, individual dignity, and the rights of children, emphasizing that children born out of invalid marriages should not be deprived of their rights and dignity.

- In Gautam Kundu v. State of West Bengal, the Supreme Court ruled that courts cannot order blood tests to challenge a child's legitimacy, and the husband must prove non-access to refute the presumption.

Presumption of Death

- The presumption of death, as outlined in Sections 107 and 108 of the Indian Evidence Act, applies when a person has been missing for an extended period, leading to the legal assumption of their death. Section 108 specifies a period of seven years for such presumption, during which the person's existence is unproven.

- In the case of Balambal v. Kannammal, the court clarified that the presumption of death can only be invoked when there is evidence supporting the presumed death or inexistence of the individual.

- In T.K Rathnam v. K. Varadarajulu, a dissenting opinion suggested that the presumption of death or existence is rebuttable and that the timing of death is a matter of evidence, not presumption.

Presumption of Sanity

- The presumption of sanity in criminal trials assumes that individuals are mentally fit and capable of understanding their actions unless proven otherwise. This legal principle safeguards the rights of defendants by acknowledging their presumed mental capacity.

Presumption of Constitutionality

- The presumption of constitutionality applies to statutes, bills, policies, and guidelines, asserting that they align with constitutional requirements. Courts generally assume that such legal documents fulfill constitutional objectives unless proven otherwise.

Presumption of Possession

- Section 110 of the Indian Evidence Act addresses the presumption of possession, where a person claiming ownership of an item in their possession is presumed to be the rightful owner. These presumptions are usually rebuttable and maintain their validity until proven otherwise by the opposing party.

3) Mixed Presumptions (Presumption of Fact and law both):

Mixed presumption refers to a combination of different types of presumptions, specifically presumption of facts and presumption of law. In the Indian legal system, the principles of mixed presumptions are outlined in the Indian Evidence Act.

The Indian Evidence Act contains provisions for both presumption of law and presumption of facts. Additionally, it grants Indian courts discretionary power to raise presumptions through principles such as "May Presume," "Shall Presume," and "Conclusive Proof."

Conclusion:

- In the case of Tukaram v. State of Maharashtra, the court examined the Mathura Rape Case and stressed the importance of certain legal presumptions. These presumptions serve a broader purpose by helping victims and guiding the direction of the case, leading to quicker and more thorough justice.

- Stephen pointed out that the presumption in question is mandatory, not permissive. Permissive presumptions, as per Section 90 of the Evidence Act, depend on the court's discretion to accept or reject facts. In contrast, mandatory presumptions provide clearer guidelines for the court in handling cases.

Best Evidence Rule : An Overview

Origin of the Best Evidence Rule

- The Best Evidence Rule, also known as the "Original Document Rule," stems from the doctrine of profert in curia. This doctrine asserted that if a party could not present the original documents in written form before the court, they would forfeit the rights conferred by those documents.

- Justice Hardwicke's rulings in cases like Ford v. Hopkins (1700) and Omychund v. Barker (1745) emphasized that only the best available evidence should be admissible in court.

- The rule emerged in response to the 16th-century practice of manual document copying by court clerks, which was prone to significant errors.

Best Evidence Rule in India:

- In India, the Best Evidence Rule is included in Sections 91 to 100 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. These sections aim to determine the authenticity of documents presented in court.

- The article explores the Best Evidence Rule within the framework of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, and highlights relevant judgments from Indian and international courts.

Best evidence rule under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Sections 91 to 100 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 focus on the best evidence rule, which prioritizes documentary evidence over oral evidence in most cases.

- These provisions highlight that documentary evidence often qualifies as the best evidence, leaving oral evidence behind.

- The best evidence rule emphasizes the importance of presenting the most reliable and accurate evidence available, which is typically found in documentary form.

Exclusion of oral evidence by the documentary evidence

Section 91: Evidence of Terms in Documents:

- The Delhi High Court in Chandrawati v. Lakhmi Chand (1988) reinforced Section 91, emphasizing that written evidence is essential for proving what is documented.

- The Allahabad High Court in Ratan Lal v. Hari Shanker (1980) ruled against using oral evidence to prove the contents of an unregistered partition deed, aligning with Section 91.

Supreme Court Clarifications:

- In Taburi Sahai v. Jhunjhunwala (1967), the Supreme Court explained that Section 91 applies to contracts, grants, and property dispositions, not to deeds like child adoption.

- The case of Bakhtawar Singh v. Gurdev Singh (1996) highlighted that courts can prefer oral over documentary evidence based on reliability, not just form.

Roop Kumar v. Mohan Thedani (2003):

- The Supreme Court stated that Section 91 embodies the best evidence rule, a principle of substantive law, and that Sections 91 and 92, while different, work together to uphold this rule.

Section 92 and its underlying principle:

Section 92 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 deals with the exclusion of oral evidence that contradicts written documents. It serves as a supplement to Section 91.

The principle behind Section 92 is that once a contract, grant, or disposition is proven through writing, oral evidence cannot be used to contradict its terms.

Section 92 allows oral evidence to qualify the terms of a document only if it is presented by a third party, not by the parties involved. This was clarified by the Supreme Court of India in the case of Vishwa Nathan v. Abdul Wajid (1986).

In the case of Nabin Chandra v. Shuna Mala (1932), the Calcutta High Court disagreed with the idea that the consideration in a document could not be challenged by proving a different consideration. This highlights the need for positive modifications to the provision based on the merits of each case.

Both Section 91 and 92 have nine exceptions to their general rules, allowing oral evidence in certain situations related to a document.

The exceptions include:

- Validity of documents. Oral evidence can be used to prove that a document is invalid.

- Matters on which document is silent. Oral evidence can fill gaps in the document, such as payment terms.

- Condition precedent. Oral evidence can establish conditions that must be met before the document's obligations take effect.

- Rescission or modification. Oral evidence can prove agreements that modify or cancel the document.

- Usages or customs. Oral evidence can prove incidents tied to specific customs or usages.

- Relation of language to facts. Oral evidence can clarify how the document's language relates to existing facts.

- Appointment of a public officer. Evidence of public officer appointments required by law to be in writing.

- Wills. Wills in India are proven through probate only.

- Extraneous facts. Oral evidence is allowed for facts referred to in the document that are not part of the case.

Ambiguous documents: Section 93 to 100:

Sections 93 to 100 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 deal with ambiguous documents, which are documents presented in court that are unclear in their language or create doubts when applied to the facts.

There are two types of ambiguity recognized by the Act:

- Patent Ambiguity (Sections 93 and 94)

- Latent Ambiguity (Sections 95-97)

Patent Ambiguity:

- Patent ambiguity refers to a defect in a document that is obvious from its surface.

- Any person with ordinary intelligence can detect this defect upon reading the document.

- Section 93 of the Act excludes evidence aimed at explaining or rectifying ambiguous documents.

- Section 94 excludes evidence against the application of documents to existing facts.

- In the case of Keshav Lal v. Lal Bhai Tea Mills Ltd (1958), the Supreme Court of India stated that extrinsic evidence cannot be used to eliminate patent defects in a document.

- Instead, the court may rely on other documentary contents to fill such defects.

Latent Ambiguity:

- Latent ambiguity refers to a defect that is not visible on the surface of the document.

- These defects become apparent only when the document is applied to specific facts.

- This is why latent defects are also known as hidden defects.

- Sections 95 to 97 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 address latent ambiguity and establish three principles related to it.

- Section 95 deals with evidence in cases where a document's language is clear, but its application to existing facts renders it meaningless.

- Section 96 addresses evidence regarding the application of language that pertains to only one of several individuals.

- Section 97 concerns evidence related to the application of language to one of two sets of facts, neither of which fully applies.

- These sections allow for the presentation of evidence to clarify how a document's language applies in specific situations.

Section 98 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 deals with evidence regarding the meaning of illegible characters in a document.

The Privy Council, in the case of Canadian-General Electric W. v. Fatda Radio Ltd. (1930), ruled that oral evidence is admissible to explain artistic words and symbols used in a document.

Landmark judgments

- The best evidence rule is an important principle in legal proceedings, especially in relation to the Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

- It emphasizes the need to present the most reliable and superior evidence available to prove a fact in court.

- This rule ensures that the evidence brought before the court is of the highest quality, preventing unfair advantages and promoting a just decision.

In this article, we will explore various landmark judgments by Indian courts that illustrate the concept of the best evidence rule when applied appropriately.

Mohan Lal Shamlal Soni v. Union Of India And Another (1991):

- The Supreme Court of India emphasized the importance of presenting the best available evidence to prove a fact in court.

- The court defined the best evidence rule as not settling for inferior proof when superior evidence is accessible.

- The decision aimed to ensure a just resolution by getting to the truth and preventing unfair advantages.

Musauddin Ahmed v. State of Assam (2009):

- The Supreme Court highlighted the duty of the prosecution to present the best evidence and draw adverse inferences when it is not provided.

- The court referred to illustration (g) of Section 114 of the Indian Evidence Act, which suggests that withholding evidence could be unfavorable to the person who withholds it.

- This principle guides courts and raises doubts on the prosecution’s case if the best evidence is not produced.

Tomaso Bruno & Anr v. State of U.P (2015):

- The Supreme Court recognized CCTV footage as crucial evidence to establish the presence of the accused at the crime scene.

- The prosecution was responsible for producing such evidence, and failure to do so raised serious doubts about their case.

- The court clarified that invoking Section 106 of the Indian Evidence Act, which places the burden of proof on the accused, required establishing the accused’s presence first.

Jitendra And Anr v. State Of M.P (2003):

- The Supreme Court emphasized the relevance of the best evidence rule in cases involving seizures, such as those under the Narcotic Drugs & Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act, 1985.

- The seized goods serve as the best evidence for the prosecution, and failing to present them raises doubts about the case.

Digamber Vaishnav v. the State Of Chhattisgarh (2009):

- The Supreme Court noted the prosecution’s failure to examine key witnesses present at the incident, withholding the best evidence.

Shivu And Anr v. R.G. High Court Of Karnataka (2007):

- The Supreme Court relied on Sir Alfred Wills’ view that the best evidence rule applies strongly to circumstantial evidence, which is inherently weaker than direct testimony.

- When the best evidence is available, substituting it with weaker evidence raises suspicions of corrupt motives.

Mohd. Aman, Babu Khan And Another v. State Of Rajasthan (1997):

- The Supreme Court disregarded evidence not supporting seizure and fingerprint matching in this case.

- The prosecution failed to establish a crucial circumstance that the seized articles were not distorted before reaching the forensic laboratory.

- Production of the seized article would have been the best evidence for seizure and fingerprint examination, and its non-production created a missing link in the evidence chain.

Conclusion:

- The best evidence rule is crucial in the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, shaping criminal law jurisprudence in India and globally.

- It guides judges in determining evidence admissibility and ensures fairness in holding accused individuals guilty based on presented evidence.

- Overall, the best evidence rule is a catalyst for evidence law in India and worldwide, promoting justice and accuracy in legal proceedings.

|

363 docs|256 tests

|

FAQs on The Indian Evidence Act - 1 - Civil Law for Judiciary Exams

| 1. What is the significance of the burden of proof in the Indian Evidence Act? |  |

| 2. How do presumptions work under the Indian Evidence Act? |  |

| 3. What is the Best Evidence Rule in the context of the Indian Evidence Act? |  |

| 4. What is the Doctrine of Res Gestae and how does it relate to hearsay evidence? |  |

| 5. What does judicial notice mean under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872? |  |