Pests and diseases and their mode of action - Plant Protection Measures, Crop Production | Crop Production Notes- Agricultural Engineering PDF Download

There are many kinds of pests. Each structure, crop, or animal have pests. You must recognize or be able to identify the common pests that you work with and their hosts. Otherwise, you may use the wrong method of control, choose the wrong pesticide, or treat too early or too often and do more harm than good. (See Chapter XI, IPM)

Goals of This Module

- Be able to recognize pests by identifying physical characteristics and damage.

- Understand how different pests reproduce and develop.

- Be familiar with how diseases affect plants.

If you know the general pattern of the pest's life cycle, the damage it does, and when it does the damage, it will help you to:

- know the best time to control the pest.

- use less pesticide, or use other methods of control.

- avoid injury to the host (plant or animal).

- avoid injury to non-target areas.

Pests

Human civilization has been competing with insects, rodents, diseases, and weeds for survival throughout its history. Historical records of plagues, famine, and pestilence fill volumes of texts. Modern man has, through his technology, created tools to combat these pests. The use of a tool, such as a pesticide, depends on the applicators ability to know when they are needed. Proper identification of the problem is the first step to proper application.

A pest is considered to be anything that:

- injures humans, animals, crops, structures, or possessions.

- competes with humans, domestic animals or crops for food, feed, or water.

- spreads disease to humans, domestic animals, or crops.

The certified applicator must know the pests that are most likely to be encountered. To be able to control these pests, you need to know the following:

- the common features of pest organisms.

- characteristics of the damage they cause.

- the biology and development of the pest.

Pests can be placed into four main categories:

- insects and closely related animals

- plant diseases

- weeds

- vertebrates

Insects

Insects, as a class of animals, outnumber all other living animals on earth. There are three times as many insects as there are animals in the rest of the animal kingdom. Insects are found everywhere; in snow, water, air, soil, hot springs, and in or on plants and animals. They compete with man and animals for food and are also considered food for a significant number of other animals. Some insects survive solely by feeding on man, for example human lice, and cannot survive for long if removed from the human body. Insects are an extremely important part of the earth's ecosystem, and despite our dread of insects we could not survive without them.

The certified applicator controlling insects must be more knowledgeable of insects than the average person. Insects can be divided into three groups by their importance to man:

- Species not considered pests. About 99 percent of all insect species are in this group. They are food for other animals (birds, fish, mammals, reptiles and other insects). Some insects, butterflies for example, are considered pleasant to look at.

- Beneficial insects. This important group includes predators and parasites that feed on pest insects, mites, and weeds. Good examples are ladybird beetles (lady bugs) and praying mantids. Pollinating insects are also very important, such as honey bees, bumble bees, moths, butterflies, and beetles. Honey bees make food for humans and animals. Some other benefits derived from insects are silk from the cocoons of silkworms, or dyes for paints made from insect secretions.

- Pest insects. This group includes the smallest number of species. These insects feed on, cause injury to, or transmit disease to humans, animals, plants, food, fiber, and structures. Some examples of pest insects are mosquitoes, fleas, termites, aphids, and beetles.

Insect Body Characteristics

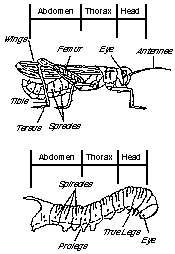

All adult insects have two characteristics in common; they have three pairs of jointed legs, and they have three body regions - the head, thorax, and abdomen.

Head. Attached to the insect head are the antennae, eyes, and mouthparts. All of these parts vary in size and shape, and can be helpful in identifying some pest insects.

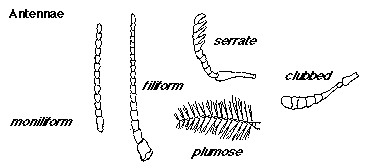

Antennae are paired appendages usually located between or below the eyes. Antennae vary greatly in size and form and are used in classifying and identifying insects. Some of the common antennae types are:

- filiform - threadlike; the segments are nearly uniform in size and shaped like a cylinder (ground beetle, cockroach).

- moniliform - look like a string of beads; the segments are similar in size and round in shape (termites).

- serrate - sawlike; the segments are more or less triangular (click beetle).

- clubbed - segments increase in diameter away from the head (Japanese beetle).

- plumose - feathery; most segments with whorls of long hair (male mosquito)

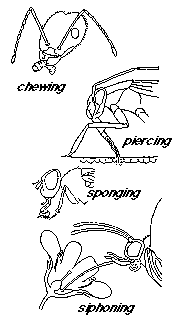

Mouthparts are different in various insect groups and are often used in classification and identification. The type of mouthpart determines how the insect feeds and what sort of damage it does. It is important that the applicator have some knowledge of the these types of insect mouth parts:

- chewing mouthparts have toothed jaws that bite and tear the food (beetles, cockroaches, ants, caterpillars, and grasshoppers).

- piercing-sucking mouthparts are usually long slender tubes that are forced into plant or animal tissue to suck out fluids or blood. (mosquitoes, aphids).

- sponging mouthparts are tongue-like structures that have spongy tips to suck up liquids or food that can be made liquid by the insect's vomit (house flies, blow flies).

- siphoning mouthparts are long tubes used for sucking nectar (butterflies, moths).

Thorax. The thorax, or middle body segment, has three pair of legs and sometimes one or two pair of wings (forewings, hindwings).

Legs come in many sizes, shapes, and functions and are helpful in identifying insects. Used for walking, running, jumping and climbing, legs have become very specialized in some insects like the large jumping leg in the grasshopper. Crickets and long -horned grasshoppers have an eardrum at the base of one of their leg segments.

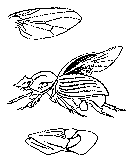

Wings also vary in size, shape, and texture. The pattern of veins on the wings of an insect are often used to identify insect species. Forewings in some insects are hard and shell-like, as in beetles. The grasshoppers have forewings that are leathery. The forewings of flies are thin, clear, and like membranes. The wings of moths, butterflies, and mosquitoes are membranous and are also covered with scales.

Abdomen. The abdomen of the insect is built of segments. Along the side of the segments are openings, called spiracles, which the insect uses to breathe. The abdomen contains digestive and reproductive organs. Parts of the abdomen used in identification include: the ovipositor, male genitalia, and cerci.

Insect Reproduction and Development

Insect reproduction. In most insects, reproduction results from the males fertilizing females. The females then lay the eggs. This is the pattern of life for most insects, but there are a few interesting variations. For example, some parasitic wasps produce eggs without ever mating. In some of these species, males are unknown. There are a few insects that give birth to live young, without the egg stage.

Egg hatching is affected by temperature, humidity, and light. Eggs come in several shapes (round, oval, flat, and elongate) and sizes. They are laid one at a time, in groups, and in floating rafts. Some insects lay eggs in capsules containing several eggs, then carry them until hatching to be sure of the survival of their young (German cockroach). Sometimes eggs are placed inside the bodies of animals, trees, and green plants. In some species, the eggs are used to identify the adult. For example, the egg capsules of cockroaches can be used to identify an infesting species of cockroach.

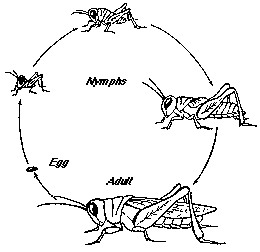

Insect Metamorphosis (development). Insects go through a series of changes as they develop from the egg to adulthood. This process of growth is called metamorphosis.

After hatching from an egg, the young insect is called either a larva, nymph, or naiad. The young feed for a while and grow. When they grow to a point where the skin cannot stretch further, the young insect molts and a new skin is formed. These stages of growth and skin shedding (called instars) differ from insect to insect and sometimes may vary with the temperature, humidity, and food supply. Generally, the heaviest feeding occurs in the last two instars. There are four types of metamorphosis:

- No metamorphosis. A few insects change very little except in size between hatching and reaching adulthood. The insect grows larger with each instar until it reaches maturity. The food and habitats of the nymphs are similar to those of the adult. The adults and nymphs are both wingless. Some examples are: springtails, firebrats, and silverfish.

- Simple or gradual metamorphosis. Insects in this group mature through three distinct stages of development before reaching maturity; egg, nymph, and adult. The nymphs resemble the adults in both form and feeding behavior, and live in the same environment. If the adult has compound eyes, the nymph will have compound eyes. However, nymphs will not be able to reproduce. The body matures gradually, with the wings and reproductive organs becoming fully developed only in the adult stage. Some examples are: cockroaches, lice, termites, scales and aphids.

- Incomplete metamorphosis. Insects with incomplete metamorphosis also pass through three stages of development; egg, naiad, and adult. There are some similarities between the adult and naiad, but there are also some dramatic differences. The naiads live in the water (aquatic) and breathe through gills. The adults have wings and live near the water, but do not have gills. Some examples are: stoneflies, mayflies, and dragonflies.

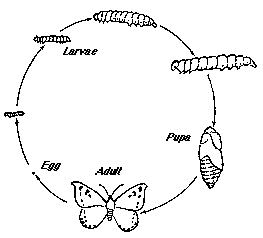

- Complete metamorphosis. This is a four stage development process, consisting of stages called; egg, larva, pupa, and adult. The young are called larvae and are familiar to everyone as caterpillars, maggots, or grubs and are entirely different from the adults. The larvae and the adults usually live in different habitats and eat different food. For example, caterpillars may live on a plant and eat leaves, while the adult butterfly flies freely, sipping nectar for food.

The larvae hatch from an egg. As they grow larger they molt and pass through one to several instars. Larvae come in several forms, shapes, and sizes such as caterpillars with many legs to maggots which are legless.

The pupa is often called the resting stage, but the insect is doing anything but resting. While in this stage, the larvae changes into an adult with legs, wings, antennae, and a fully functional reproductive system.

Insect-Like Pests

Spiders, ticks, mites, sowbugs, pillbugs, millipedes, and centipedes resemble insects in habit, appearance, life cycle, and size. Although they are not insects, they are often mistaken for them. The pesticide applicator needs to be familiar with these pests when evaluating a problem.

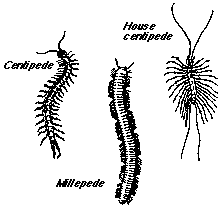

Centipedes and Millipedes.

Centipedes are flat, long, worm-like animals, with each body segment having one pair of legs. They have chewing mouthparts. Some can give painful bites to humans. Centipedes are found in protected places under tree bark or in rotting logs. They are very fast and predaceous, capturing and feeding on insects, spiders, and other small animals. All centipedes have poisonous jaws.

Millipedes have a cylindrical shape, like an earthworm, and have many legs, two pair on each body segment. The mouth parts are adapted to feeding on decaying organic material. Thus, they are found in decaying leaf litter, rotting logs, and near damp debris near foundations.

Millipedes and centipedes have no metamorphosis. They only change in size between hatching from the egg and reaching the adult stage.

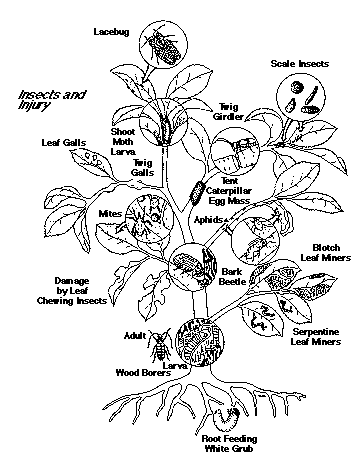

Insects and Injury

Crustaceans. This class of animals (lobsters, shrimp) are nearly all aquatic (living in water) but there are members living on land that may become pests and are often thought to be insects. Sowbugs (often called pillbugs) are black, gray, or brown and are capable of rolling up into a ball. Sowbugs are found in damp decaying wood or under objects such as stones, boards, or blocks. There have been cases when crustaceans have been considered pests of cultivated plants in some areas, but usually are found living in damp basements or garages where people don't want them.

Arachnids. This group, which consists of spiders, mites, ticks, and scorpions all have eight legs and only two body regions. Arachnids are wingless and lack antennae. They mature through gradual metamorphosis that includes both larval and nymphal stages. Eggs hatch into larvae (six legs) which molt into nymphs (eight legs) and then adults. Spiders and scorpions have chewing mouthparts. Ticks and mites have a modified version of piercing -sucking mouthparts. Ticks are of particular interest because they sometimes transmit diseases such as Lyme disease and Rocky Mountain Spotted fever to man during feeding.

Plant Diseases

A plant disease is any harmful condition that alters a plants growth, appearance, or function. Diseases are caused by biological agents called pathogens. They are of interest to pesticide applicators because some diseases can be cured with pesticides, while other pesticides can prevent the pathogen from infecting the host plant. Pathogens include bacteria, fungi, viruses, and nematodes. They are spread by wind, rain, insects, birds, snails, slugs, and earthworms. In addition, pathogens can be carried by transplanted soil, nursery grafts, vegetative propagation, contaminated equipment and tools, infected seed, pollen, dust storms, irrigation water, and people.

Plant pathogens are parasites which live and feed on the host plant. In order for a disease to develop, a pathogen must be present, the host plant must be susceptible, and the environment must be favorable for development of the pathogen. Temperature and moisture are especially important to the success of the pathogen.

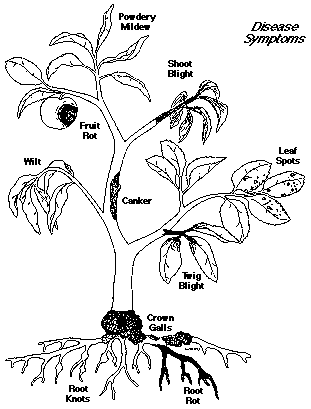

The disease starts with the arrival of the pathogen on the plant. If the parasite can get into the plant, the infection starts. Three main ways a plant responds to a disease are:

- overdevelopment of tissue, galls, swellings, and leaf curls.

- underdevelopment of tissue, stunting, lack of chlorophyll, and incomplete development of organs.

- death of tissue, blights, leaf spots, wilting, and cankers.

Bacteria. Bacteria are microscopic (can only be seen with a microscope), one-celled organisms that reproduce by single cell division. Bacteria numbers multiply quickly under warm, humid weather conditions. Bacteria may attack any part of a plant, either above or below the soil surface. Several of the leaf spot and rot diseases are caused by bacteria.

Fungi. Fungi are plants that lack chlorophyll and cannot make their own food. Fungi are the most frequent pathogens on plants. They feed off other living organisms or live on dead or decaying organic matter. Most of the time fungi are beneficial because they help release nutrients from dead plants and animals, adding to the fertility of the soil. Fungi reproduce with spores, which function about the same way seeds do. Fungus spores are usually microscopic and are produced in high numbers. Most spores die because they do not find a host to feed on, though some can survive for months without a host. High humidity (above 90 percent) is essential for spore germination and active growth. Mildew and smut are good examples of fungal diseases.

Viruses. Viruses are tiny organisms smaller than bacteria and cannot be seen with an ordinary microscope. Viruses are usually recognized from the symptoms they induce on the infected plant. They depend on other living organisms for food and cannot live long on their own. Viruses invade healthy plants through wounds or during pollination. Insects that feed with piercing-sucking mouthparts (aphids, whiteflies, leafhoppers), as well as chewing insects (beetles) can transmit viruses while feeding. Viruses can also be spread by nematodes. Practically all plants can be infected by viruses.

Mycoplasmas are the smallest known independently living organisms. Unlike viruses, they can exist apart from the host organism. Mycoplasmas obtain their food from plants. Yellows disease and some stunts are caused by mycoplasmas.

Nematodes. Nematodes are tiny (microscopic) eel or worm-like organisms. Nematodes destroy root systems while feeding, which causes a loss in the uptake of water and minerals by the p lant, thus weakening the plant. Common symptoms are wilting, stunting, and lack of vigorous growth under good growing conditions. Nema todes may also spread plant diseases while feeding. Nematodes feed by sucking the contents of a cell through a hypodermic-like mouth inser ted into a cell. Not all nematodes feed on roots. Some foliar feeding n ematodes attack chrysanthemums and leave triangles of brown, dried tissue that develop on the leaves late in the season. Some nematodes are parasitic to insects.

Weeds

Any plant can be considered a weed when it is growing where it is not wanted. This is a very broad definition, but consider the following problems caused by weeds.

Weeds can harm man by:

- causing skin irritation (poison ivy).

- causing hay fever (ragweed).

- harboring pests such as rodents, ticks, or insects.

Weeds can harm desirable plants by:

- releasing toxins in the soil which inhibit the growth of desirable plants.

- contaminating the product at harvest.

- competing for water, nutrients, light, and space.

- harboring pest insects, mites, vertebrates, or plant disease agents.

Weeds can harm grazing animals by:

- poisoning.

- causing an "off-flavor" in milk and meat.

Weeds may become pests in water by:

- hindering fish growth and reproduction.

- increasing mosquito reproduction.

- hindering boating, fishing, and swimming.

- clogging irrigation ditches, drainage ditches, and channels.

Weeds are dangerous and undesirable on rights-of-way because they:

- block vision, road signs, and crossroads.

- increase road maintenance costs.

Plant Development Stages

After a plant seed has germinated, development can be separated into four stages:

- seedling - very small, very vulnerable plantlets.

- vegetative - rapid growth, root stems, a nd foliage produced. Nutrients and water move rapidly throughout the plant.

- seed production - becomes the priority for energy use. Water and nutrient uptake are slow and directed to flower, fruit, and seed production.

- maturity - movement of water and nutrients slow down, energy production is low.

Duration of the Weed

Annuals. Plants that grow from seed, mature, and produce seed for the next generation in one year or less are called annuals. This group has many grass-like weeds (crabgrass) and broadleaved (pigweed) m embers. There are two basic types of annual weeds:

Summer annuals grow from seeds that sprout in the spring. These weeds grow, mature, produce seed, and die before winter. Some examples are: foxtail, pigweed, lambsquarters, and crabgrass.Winter annuals grow from seeds which sprout in the fall. These weeds mature, produce seed, and die before the next summer. Some examples are: henbit, common chickweed, and annual bluegrass.

Biennials. These plants have a two-year life cycle. During the first year, they grow from seed and develop a heavy root and compact cluster of leaves (called a rosette). During the second year, they mature, produce seed, and die. Some examples are: bull thistle and burdock.

Perennials. When plants live more than two years they are called perennials. Perennials may mature and reproduce in the first year, but they will repeat the cycle for several years or maybe indefinitel y. Some perennial plants die back each winter. Others, such as trees, may lose their leaves but do not die back. Most perennials grow from seed and many produce tubers, bulbs, rhizomes (below-ground root-like stems), or stolons (above-ground stems that produce roots).

Simple perennials usually reproduce with the use of seeds. They also may reproduce when root pieces are cut by cultivation. The pieces then grow into new plants. Examples: trees, shrubs, plantain, and dandelions.Bulbous perennials may reproduce by seed bulblets, or bulbs. Wild garlic produces seed and bulblets above ground and bulbs below ground.Creeping perennials produce seed, rhizomes (below-ground stems), or stolons (above-ground stems that can produce roots). Examples: Johnsongrass, field bindweed, and Bermudagrass.

Weed Identification

Arrangement of Leaves

Alternate - one leaf found at each level on the stem.Opposite - two leaves opposite each other or paired.Whorled - three or more leaves at each level on the stem.

Leaf Structure

Simple - the leaf blade is a single piece and not divided into separate leaflets.Compound - the leaf blade is divided into several leaf-like parts called leaflets.

Leaf Shape

Ovate - Egg-shaped, elliptical, broadest at the base.Lanceolate - lance-shape, are longer than ovate and usually pointed at the tip.Linear - long and narrow with parallel sides (grasses).

Arrangement of the Flowers

Inflorescence - in a definite cluster, usually at the top of the plant.Axillary - along the stem of the plant in the angles (leaf axils) between the foliage, leaves and the stem.

Flower Parts

Petals - the expanded and usually colorful parts of the flower.Sepals - the greenish hull surrounding the flower when it is budding.

Major Classes of Weeds

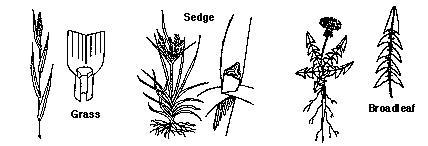

Grasses. Leaves of grasses are narrow, stand upright, and have parallel veins. When the seedlings sprout, they have only one leaf. Grasses grow from a point (growing point) located below the soil surface, thus the growing point is sheltered. This is why grass can be mowed without killing the plant. Most grasses have fibrous root systems. Grasses have both annual and perennial species.

Sedges. These are similar to grasses, but they have triangular stems and three rows of leaves. They are sometimes listed under grasses on the pesticide label. These plants often are found in wet places, but are principal pests in fertile, well-drained soils. Yellow and purple nutsedge are perennial weed species and produce rhizomes and tubers.

Broadleaves. Seedlings of broadleaves have two leaves that emerge from the seed. The veins of their leaves are netlike. Broadleaves usually have a taproot and their root system is relatively coarse. All broadleaf plants have exposed growing points that are at the end of each stem and in each leaf axil. The perennial broadleaf plants may also have growing points on roots and stems above and below the surface of the soil. The broadleaves have species with annual, biennial, and perennial life cycles.

Vertebrate Pests

Vertebrate animals all have a jointed backbone. Humans are vertebrates, as are mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Like insects, most vertebrate animals are not pests and can be an enjoyable part of our environment.

There are situations when vertebrates can be pests. Sometimes birds, rodents, raccoons, or deer may damage crops or ornamentals. Birds and rodents eat the same food as humans and often ruin more food than they eat. Mammal and bird predators of livestock and poultry cause financial losses to farmers and ranchers each year. Great flocks of roosting birds can soil buildings.

There are also those in the vertebrate group (particularly rodents) that are a hazard to public health when they are in homes, restaurants, offices, or warehouses. Rodents, other mammals, and some birds are potential reservoirs of serious diseases of humans and domestic animals. Some examples are: rabies, plague, and tularemia.