Motion of an Object in a Viscous Fluid | Basic Physics for IIT JAM PDF Download

A moving object in a viscous fluid is equivalent to a stationary object in a flowing fluid stream. (For example, when you ride a bicycle at 10 m/s in still air, you feel the air in your face exactly as if you were stationary in a 10-m/s wind.) Flow of the stationary fluid around a moving object may be laminar, turbulent, or a combination of the two. Just as with flow in tubes, it is possible to predict when a moving object creates turbulence. We use another form of the Reynolds number  , defined for an object moving in a fluid to be

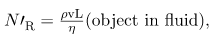

, defined for an object moving in a fluid to be

where L is a characteristic length of the object (a sphere’s diameter, for example), ρ the fluid density, η its viscosity, and v the object’s speed in the fluid. If is less than about 1, flow around the object can be laminar, particularly if the object has a smooth shape. The transition to turbulent flow occurs for

is less than about 1, flow around the object can be laminar, particularly if the object has a smooth shape. The transition to turbulent flow occurs for  between 1 and about 10, depending on surface roughness and so on. Depending on the surface, there can be a turbulent wake behind the object with some laminar flow over its surface. For an

between 1 and about 10, depending on surface roughness and so on. Depending on the surface, there can be a turbulent wake behind the object with some laminar flow over its surface. For an between 10 and 106 , the flow may be either laminar or turbulent and may oscillate between the two. For

between 10 and 106 , the flow may be either laminar or turbulent and may oscillate between the two. For greater than about 106, the flow is entirely turbulent, even at the surface of the object. Laminar flow occurs mostly when the objects in the fluid are small, such as raindrops, pollen, and blood cells in plasma. Does a Ball Have a Turbulent Wake? Calculate the Reynolds number

greater than about 106, the flow is entirely turbulent, even at the surface of the object. Laminar flow occurs mostly when the objects in the fluid are small, such as raindrops, pollen, and blood cells in plasma. Does a Ball Have a Turbulent Wake? Calculate the Reynolds number  for a ball with a 7.40-cm diameter thrown at 40.0 m/s.

for a ball with a 7.40-cm diameter thrown at 40.0 m/s.

Strategy

We can use  to calculate

to calculate  , since all values in it are either given or can be found in tables of density and viscosity.

, since all values in it are either given or can be found in tables of density and viscosity.

Solution

yields

yields

Discussion

This value is sufficiently high to imply a turbulent wake. Most large objects, such as airplanes and sailboats, create significant turbulence as they move. As noted before, the Bernoulli principle gives only qualitatively-correct results in such situations.One of the consequences of viscosity is a resistance force called viscous drag Fv that is exerted on a moving object. This force typically depends on the object’s speed (in contrast with simple friction). Experiments have shown that for laminar flow (

less than about one) viscous drag is proportional to speed, whereas for

less than about one) viscous drag is proportional to speed, whereas for  between about 10 and 106, viscous drag is proportional to speed squared. (This relationship is a strong dependence and is pertinent to bicycle racing, where even a small headwind causes significantly increased drag on the racer. Cyclists take turns being the leader in the pack for this reason.) For

between about 10 and 106, viscous drag is proportional to speed squared. (This relationship is a strong dependence and is pertinent to bicycle racing, where even a small headwind causes significantly increased drag on the racer. Cyclists take turns being the leader in the pack for this reason.) For greater than 106, drag increases dramatically and behaves with greater complexity. For laminar flow around a sphere, Fv is proportional to fluid viscosity η , the object’s characteristic size L , and its speed v . All of which makes sense—the more viscous the fluid and the larger the object, the more drag we expect. Recall Stoke’s law Fs = 6πrηv. For the special case of a small sphere of radius R moving slowly in a fluid of viscosity η, the drag force Fs is given by Fs = 6πRηv

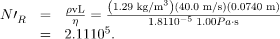

greater than 106, drag increases dramatically and behaves with greater complexity. For laminar flow around a sphere, Fv is proportional to fluid viscosity η , the object’s characteristic size L , and its speed v . All of which makes sense—the more viscous the fluid and the larger the object, the more drag we expect. Recall Stoke’s law Fs = 6πrηv. For the special case of a small sphere of radius R moving slowly in a fluid of viscosity η, the drag force Fs is given by Fs = 6πRηv(a) Motion of this sphere to the right is equivalent to fluid flow to the left. Here the flow is laminar with

less than 1. There is a force, called viscous drag Fv, to the left on the ball due to the fluid’s viscosity.

less than 1. There is a force, called viscous drag Fv, to the left on the ball due to the fluid’s viscosity. (b) At a higher speed, the flow becomes partially turbulent, creating a wake starting where the flow lines separate from the surface. Pressure in the wake is less than in front of the sphere, because fluid speed is less, creating a net force to the left F′v that is significantly greater than for laminar flow. Here

is greater than 10.

is greater than 10. (c) At much higher speeds, where

is greater than 106 , flow becomes turbulent everywhere on the surface and behind the sphere. Drag increases dramatically.

is greater than 106 , flow becomes turbulent everywhere on the surface and behind the sphere. Drag increases dramatically.

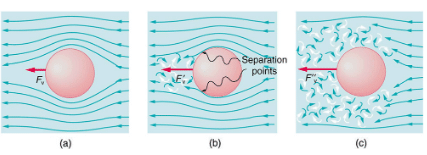

An interesting consequence of the increase in Fv with speed is that an object falling through a fluid will not continue to accelerate indefinitely (as it would if we neglect air resistance, for example). Instead, viscous drag increases, slowing acceleration, until a critical speed, called the terminal speed, is reached and the acceleration of the object becomes zero. Once this happens, the object continues to fall at constant speed (the terminal speed). This is the case for particles of sand falling in the ocean, cells falling in a centrifuge, and sky divers falling through the air. Some of the factors that affect terminal speed. There is a viscous drag on the object that depends on the viscosity of the fluid and the size of the object. But there is also a buoyant force that depends on the density of the object relative to the fluid. Terminal speed will be greatest for low-viscosity fluids and objects with high densities and small sizes. Thus a skydiver falls more slowly with outspread limbs than when they are in a pike position—head first with hands at their side and legs together.

Take-Home Experiment: Don’t Lose Your Marbles

By measuring the terminal speed of a slowly moving sphere in a viscous fluid, one can find the viscosity of that fluid (at that temperature). It canbe difficult to find small ball bearings around the house, but a small marble will do. Gather two or three fluids (syrup, motor oil, honey, olive oil, etc.) and a thick, tall clear glass or vase. Drop the marble into the center of the fluid and time its fall (after letting it drop a little to reach its terminal speed). Compare your values for the terminal speed and see if they are inversely proportional to the viscosities . Does it make a difference if the marble is dropped near the side of the glass?

There are three forces acting on an object falling through a viscous fluid: its weight w, the viscous drag Fv, and the buoyant force FB.

Section Summary

1. When an object moves in a fluid, there is a different form of the Reynolds number

which indicates whether flow is laminar or turbulent.2. For N′R less than about one, flow is laminar.

which indicates whether flow is laminar or turbulent.2. For N′R less than about one, flow is laminar.3. For N′R greater than 106, flow is entirely turbulent.

Conceptual Questions

What direction will a helium balloon move inside a car that is slowing down—toward the front or back? Explain your answer.

Will identical raindrops fall more rapidly in 5 C air or 25 C air, neglecting any differences in air density? Explain your answer.

If you took two marbles of different sizes, what would you expect to observe about the relative magnitudes of their terminal velocities?

|

217 videos|156 docs|94 tests

|