19 August 2020: The Hindu Editorial Analysis | Additional Study Material for UPSC PDF Download

1. TIME FOR INDIA AND NEPAL TO MAKE UP

GS 2- India and its neighborhood- relations

Context

(i) Nepal-India dispute over the Himalayan territory of Limpiyadhura was flared up in May.

(ii) New Delhi opinion-makers presented it as the doing of an upstart nation run by a renegade(traitor) Prime Minister thumbing its nose at India, that too at Beijing’s instigation(provocation).

(iii) Kathmandu’s polity bristled (stand up) at the accusation and the entire political spectrum came together in nationalist climax to adopt a new map which included Limpiyadhura.

(iv) There has been much blood-letting over the past four months, with one side (India) petulant(impatient), the other angry.

(v) New Delhi pointedly says it will sit for talks only after the COVID-19 pandemic.

(vi) In turn, he abandoned diplomatic decorum(behavior) to question India’s commitment to ‘satyameva jayate’ and then claimed the true birthplace of Lord Ram was situated in present-day Nepal.

(vii) This tailspin must be halted(stopped) so that the most exemplary inter-state relationship of South Asia may recover.

(viii) De-escalation must happen before the social, cultural and economic flows across the open border suffer long-term damage. Fear of Abandonment

Fear of Abandonment

(i) From the Kathmandu perspective, Indian diplomacy seems increasingly unresponsive under the centralised control of the Prime Minister’s Office.

(ii) With regard to China, New Delhi has nurtured a paralysing paranoia regarding the Himalayan range that goes back to the 1962 debacle, a condition now worsened by the Galwan intrusion.

(iii) Nepal, Bhutan and India’s own Himalayan tracts are regarded merely as strategic buffers.

(iv) In addition, there is the constant preoccupation with neighbours who have supposedly ‘sold out’ to China.

(v) A confident nation-state without fear of abandonment would have behaved differently on Limpiyadhura.

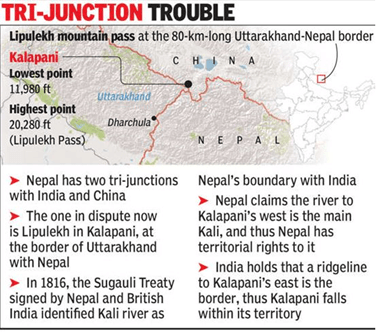

(vi) The cause of the chasm(breach) that has opened up between Kathmandu and Delhi relates to the disputed ownership of the triangle north of Kumaon, including the Limpiyadhura ridgeline, the high pass into Tibet at Lipu Lek, and the Kalapani area hosting an Indian Army garrison.

(vii) New Delhi’s position on the dispute is based on its decades-long possession of the territory, coupled with Kathmandu’s implied acquiescence(consent) through its silence and the omission of Limpiyadhura on its own official maps.

(viii) Kathmandu responded with sensitivity to Indian strategic concerns before and after the 1962 China-India war by allowing the Indian army post to be stationed within what was clearly its territory at Kalapani and not publicly demanding its withdrawal.

(ix) However, following the advent of democracy in 1990, the demand for evacuation of Kalapani gained momentum.

(x) Kathmandu’s diplomats deny the accusation of passivity over the decades, saying that as the weaker power, Nepal preferred quiet diplomacy and that Kalapani had never been off the table since talks began in the early 1980s.

(xi) As for the ‘possession’ argument, if control of a disputed region were to confirm ownership, then what of China’s continuous hold over Aksai Chin since Independence?

(xii) Regarding the suggestion of Nepal acting on China’s ‘behest’, in fact Kathmandu considers China complicit on Lipu Lek, and has lodged strong protests with Beijing regarding its joint plans with New Delhi on use of the high pass.

Road to Lipu Lek

(i) The two governments have agreed that a territorial dispute exists on upstream Kali and have assigned negotiators.

(ii) A border demarcation team was able to delineate 98% of the 1,751 km Nepal-India frontier, but not Susta along the Gandaki flats and the upper tracts of the Kali.

(iii) In 2014, India’s External Affairs Minister agreed to the establishment of a Border Working Group, which was announced by Prime Minister Modi and Prime Minister Sushil Koirala. It too failed to make headway.

(iv) In August 2019, India’s Minister for External Affairs S. Jaishanker and Nepal’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Pradip Gyawali assigned the task to the two Foreign Secretaries.

(v) That was where matters rested, with India dragging its feet on the Foreign Secretaries’ meeting, when things went awry(bad).

(vi) Nepal has been keen to sort out the matter away from the limelight.

(vii) It was after India published its new political map in November following the bifurcation(division) of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh.

(viii) The pressure arose for Kathmandu to put out its own map incorporating the Limpiyadhura finger. The government cartographers(one who draws maps) got busy.

(ix) Knowing full well the dangers of taking on the Indian lion, Prime Minister Oli held off on the map release while waiting for New Delhi to come to the table.

(x) But diplomacy did not get a chance, with the Ministry of Defence evidently having kept even South Block in the dark.

(xi) It was until India’s Defence Minister Rajnath Singh, with much fanfare, digitally ‘inaugurated’ the unfinished track to Lipu Lek on May 8.

(xii) Prime Minister Oli’s position became untenable(undefendable), and he proceeded with the constitutional amendment to certify the new map.

(xiii) Indian diplomats lobbied to keep Nepal’s Parliament from adopting the amendment, but Kathmandu needed it for the sake of cartographic parity with India in future talks.

(xiv) Truth be told — that the Limpiyadhura triangle exists now on the maps of both countries should not obstruct negotiations.

(xv) The smaller area of Kalapani, too, has remained on the maps of both countries for decades. And, life has gone on.

Dousing the Volcano

(i) The ice was broken on August 15 when Prime Minister Oli called Prime Minister Modi on the occasion of India’s Independence Day, but that is just the beginning.

(ii) Talks must be held, for which the video conference facility that has existed between the two Foreign Secretaries must be re-activated.

(iii) Delay will wound the people of Nepal socially, culturally and economically.

(iv) As the larger country, India may think it will hurt less, but only if it disregards its poorest citizens from Purvanchal to Bihar and Odisha, who rely on substantial remittance from Nepal.

(v) India does have experience of successfully resolving territorial disputes with Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and even Pakistan bilaterally and through third-party adjudication(decision).

(vi) Given political will at the topmost level, it should be possible to douse(extinguish) the Limpiyadhura volcano just as quickly as it has erupted.

Need to De-Escalate

(i) One difficulty is the apparent absence of backchannel diplomacy between the two capitals, which helped in ending the 2015 blockade.

(ii) Today, India’s Prime Minister’s Office exercises such exclusive power that all channels have dried up.

(iii) There is an immediate need to de-escalate and compartmentalise. The first requires verbal restraint on the part of Prime Minister Oli and India’s willingness to talk even as the pandemic continues.

(iv) While India’s Foreign Office has thankfully remained restrained in its statements, India is required to maintain status quo(existing affair) in the disputed area.

(v) This means halting(stopping) construction on the Lipu Lek track, which is the immediate cause of the present crisis.

(vi) With the Prime Ministers setting the tone, the negotiating teams must meet with archival papers, treaties and agreements, administrative records, communications, maps and drawings.

(vii) The formal negotiations should begin with ab initio(beginning) public commitment by both sides to redraw their respective maps according to the negotiated settlement as and when it happens.

Conclusion

(i) Not to prejudge the outcome, if Nepal were to gain full possession of Limpiyadhura, it should declare the area a ‘zone of peace and pilgrimage’.

(ii) The larger area must be demilitarised by both neighbours to ensure security for themselves, while the Kailash-Manasarovar route is kept open for pilgrims.

(iii) The idea is certainly worth a thought: a Limpiyadhura Zone of Peace and Pilgrimage.

2. RESURRECTING THE RIGHT TO KNOW

GS 2- Important aspects of governance, transparency and accountability

Context

(i) A significant development in the right to information campaign has largely gone unnoticed.

(ii) The resurrection(revival) of the right to know is momentous considering that we are increasingly witnessing an unfortunate denial of information while forgetting the right to know.

Releasing the Report

(i) A High Level Committee (HLC) chaired by a retired judge of the Gauhati HC and also including the Advocates General of two Northeast States was constituted by the Home Ministry on July 15, 2019.

(ii) Its mandate was, among others, to recommend measures to implement Clause 6 of the Assam Accord and define “Assamese People”.

(iii) The HLC finalised its report by mid-February 2020 and submitted it to the Assam Chief Minister soon after. He handed over the report to the Union Home Minister on March 20.

(iv) With the Central government apparently “sitting idle” over the report, the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU), which was represented in the HLC, released the report on August 11.

(v) The proffered reasons for the release were the Central government’s inaction on the report and the people’s right to know.

(vi) Sitting idle over a report is not an uncommon phenomenon. The Vohra Committee report on the alleged nexus(link) between politicians and criminals was kept under wraps(hiding) for almost two years.

(vii) It was tabled in Parliament following a public uproar(agitation) on the murder of Naina Sahni by a prominent politician.

Right to Know

(i) The right to know was recognised nearly 50 years ago and is the foundational basis for the right to information.

(ii) In State of U.P. v. Raj Narain (1975), the Supreme Court carved out a class of documents that demand protection even though their contents may not be damaging to the national interest.

(iii) For example, Cabinet papers, foreign office despatches, papers regarding the security of the state and high-level interdepartmental minutes.

(iv) A pragmatic view was told by Justice Mathew who held that “the people of this country have a right to know every public act, everything that is done in a public way, by their public functionaries.

(v) They are entitled to know the particulars of every public transaction in all its bearing.

(vi) The right to know, which is derived from the concept of freedom of speech, though not absolute, is a factor which should make one wary, when secrecy is claimed for transactions which can, at any rate, have no repercussion(consequence) on public security.”

(vii) Our Supreme Court held that there is no provision by which Parliament had vested power in the government either to restrain the publication of documents marked as secret or from placing such documents before a court of law which may have been called upon to adjudicate a legal issue concerning the parties.

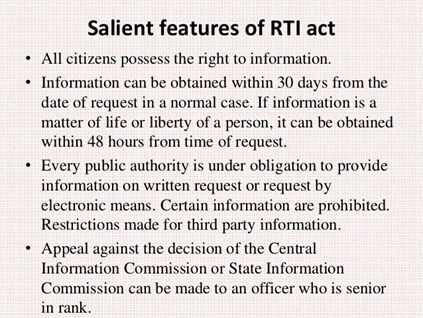

(viii) Justice K.M. Joseph referred to Section 8(2) of the Right to Information Act, 2005 which provides that a citizen can get a certified copy of a document even if the matter pertains to security or relationship with a foreign nation, if a case is made out.

(ix) Therefore, it is clear that the right to know can be curtailed only in limited circumstances and if there is an overriding public interest.

Being More Transparent

(i) Keeping in mind the view expressed by the Supreme Court over nearly 50 years, it is clear that the Official Secrets Act is not attracted to the disclosure of the HLC report.

(ii) There is no doubt that a bold and progressive decision has been taken by AASU to release the report in public interest.

(iii) Hopefully, this will encourage governments to effectuate the citizen’s right to know and be more transparent in public interest, as long as the security of the country is not jeopardised.

Conclusion

As observed by the Supreme Court in S.P. Gupta: “If secrecy were to be observed in the functioning of government and the processes of government were to be kept hidden from public scrutiny, it would tend to promote and encourage oppression, corruption and misuse or abuse of authority, for it would all be shrouded(hidden) in the veil(cover) of secrecy without any public accountability.”

3. ERRING ON THE SIDE OF CAUTION: ON SEX-SELECTIVE ABORTION RULES

GS 2- Important aspects of governance, transparency and accountability

Context

(i) Last week, the Supreme Court deferred a pronouncement on the legality of the Centre’s now-lapsed controversial notification relating to the rules of the law banning sex-selective abortions.

(ii) The judges viewed the matter as closed for now.

(iii) The April 4 notification pertaining to the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) (PCPNDT) Act was left to expire by the government on June 30.

(iv) The apex court similarly erred(error) on the side of caution in June, choosing not to stay the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare’s gazette notification.

(v) The inference was that such an option would be warranted only if the suspension of relevant rules was extended beyond June.

(vi) The petitioner’s concerns have thus largely been allayed(lessened) that the April 4 notification loosening the rules, ostensibly(apparently) to cope with the pandemic, would dilute(weaken) the law.

Suspension of Rules

(i) One of the impugned(challenged) rules requires a five-yearly renewal of registration of genetic laboratories, ultrasound clinics and imaging centres, subject to the fulfilment of eligibility criteria.

(ii) Another mandates these diagnostic establishments to submit monthly records on the conduct of pregnancy-related procedures to the designated authority.

(iii) State governments and Union Territories are required to furnish quarterly reports to the Centre on the implementation of the law.

(iv) The Union Health Ministry had maintained that various procedural deadlines were relaxed in the wake of the public health crisis and that such flexibility would in no way jeopardise(harm) the larger objectives of the law.

(v) On the other hand, activists saw no rationale whatsoever behind the suspension of rules, since the operation of diagnostic laboratories had been declared essential services.

(vi) They were understandably apprehensive that the freeze(stop) would result in large-scale violations.

(vii) It is one thing to condone(disregard) delays in the completion of formalities via an administrative order, but altogether another to declare a freeze via a gazette notification, they argued.

(viii) In any case, the 25-year jurisprudence around the PCPNDT legislation does not justify a sanguine(positive) approach on the enforcement of its various provisions.

(ix) A case in point is the ongoing litigation regarding the eligibility of medical practitioners to conduct ultrasound procedures.

(x) In February 2016, the Delhi High Court struck down the requirement under the 2014 PCPNDT rules of a six-month training period for personnel carrying out ultrasonography.

(xi) In challenging that ruling in the Supreme Court, the Indian Radiological and Imaging Association (IRIA) stressed the lack of preparation in an MBBS programme to conduct ultrasound procedures, which was part of the discipline of radiology.

(xii) IRIA also cited the relevant Medical Council of India guidelines based on the law.

Court Strictures

(i) The Supreme Court stayed the Delhi High Court judgment in 2018 as an interference in legislative policy intended to further the objectives of the law in the face of grave misuse of pre-natal diagnostic procedures.

(ii) The Court last year ruled that the non-maintenance of medical records as per Section 23 of the PCPNDT Act could serve as a conduit in the grave offence of foeticide.

(iii) The Bench hence dismissed the plea of the Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecological Societies of India to treat inaccuracies in paperwork as clerical errors.

(iv) In its 2016 judgment, in response to the petition, the Court authorised the seizure of illegal equipment from clinics and the suspension of their registration as well as speedy disposal of relevant cases by the States.

(v) Crucially, the alarming decline witnessed in recent decades in India’s sex ratio at birth calls for an uncompromising adherence to public policy, more than is evident from evolving case law.

|

21 videos|562 docs|160 tests

|

FAQs on 19 August 2020: The Hindu Editorial Analysis - Additional Study Material for UPSC

| 1. What is the significance of The Hindu Editorial Analysis for UPSC exam preparation? |  |

| 2. How can The Hindu Editorial Analysis help in improving language skills for UPSC exam? |  |

| 3. Are the Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) related to The Hindu Editorial Analysis available online? |  |

| 4. How can I make the most out of The Hindu Editorial Analysis for UPSC exam preparation? |  |

| 5. What are some alternative sources for editorial analysis if I cannot access The Hindu newspaper? |  |