The Hindu Editorial Analysis- 2nd Sept, 2020 | Additional Study Material for UPSC PDF Download

1. INEVITABLE COLLAPSE: ON STEEPEST CONTRACTION OF GDP-

GS 3- Indian Economy and issues relating to planning, mobilization of resources, growth, development and employment

Context

(i) The inevitable(not happened before) has happened.

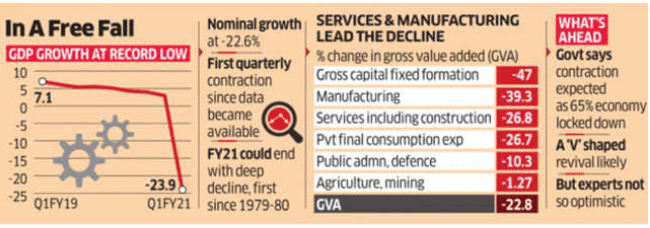

(ii) India’s GDP suffered its steepest contraction on record in the April-June quarter, as output shrank 23.9% from a year earlier, provisional data show.

Grim Scenario

(i) It is evident that the stringent COVID-19 lockdowns in force through the first third of the quarter, and substantially in May, hollowed out(less) demand.

(ii) Private consumption spending, which accounts for almost 60% of GDP, contracted 26.7% as consumers abjured(rejected) almost all discretionary spending.

(iii) And exports, which contribute to a fifth of GDP and reflect overseas demand for Indian goods and services, shrank by nearly 20%.

(iv) Investment activity was the worst-hit, collapsing 47% and shrinking in share of GDP to about 22% from 32% a year earlier as larger businesses conserved cash and refrained from any capital spending in the face of uncertainty, and smaller firms prioritised survival.

(v) Across the real economy, every single industry and services sector shrank with the solitary exception of agriculture, which grew 3.4% and outpaced the year earlier quarter’s 3% expansion.

(vi) Construction suffered the most, plunging(decreasing) 50%, followed by the omnibus(several) services category — trade, hotels, communication, transport and broadcasting — which shrank 47%, hit by the pandemic-linked restrictions.

(vii) Manufacturing too took a severe beating, contracting 39% as demand for products deemed non-essential evaporated, and factories, even after reopening, struggled to run amid shortages of labour and added safety norms.

Dilemma

(i) It was left to the government to keep the bottom from falling out on demand as the Centre’s pandemic mitigation expenditure helped expand its consumption spending by 16.4% year-on-year and softened the overall blow to GDP.

(ii) The fiscal deficit has already exceeded the full-year’s budgeted target in just the first four months, and also the revenue receipts are impacted by the economic contraction.

(iii) Given the situation, the government is unlikely to maintain a similar trend in expenditure growth over the next three quarters.

(iv) Unless, of course, it is prepared to forsake(give up) its vaunted(praised) fiscal conservatism and finds innovative ways to mobilise resources.

(v) The still rising trajectory of new COVID-19 infections and a high level of job losses and income erosion are also sure to retard any recovery in momentum.

(vi) If the latest survey-based data from IHS Markit show manufacturing PMI for August signalling growth for the first time in five months, the same researcher’s findings also stress that “job shedding continues at a strong rate” in the industry.

(vii) Equally significantly, the output numbers which are expected to undergo revision given the acknowledged difficulties in collecting data, do not capture a swathe(large part) of informal sector activity that was severely impacted.

(viii) Agriculture too faces headwinds(breaks) in the form of higher-than-ideal rainfall in August in several key crop growing regions in western and central India.

(ix) And with the impact of recent farm market ordinances yet to play out, it may be a while before the end of the tunnel(problems disappearing) is sighted.

Conclusion

With COVID-19 hitting private consumption, demand recovery will hinge(depend) on govt. spending.

2. DISRUPTION AND CHALKING OUT A NEW IDEA FOR EDUCATION-

GS 2- Issues relating to development and management of Social Sector/Services relating to Education

Context

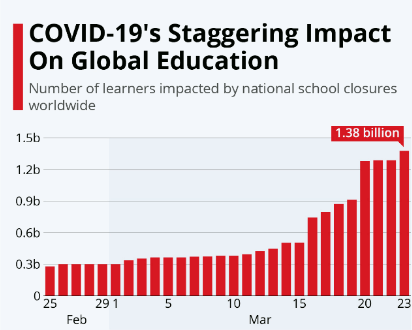

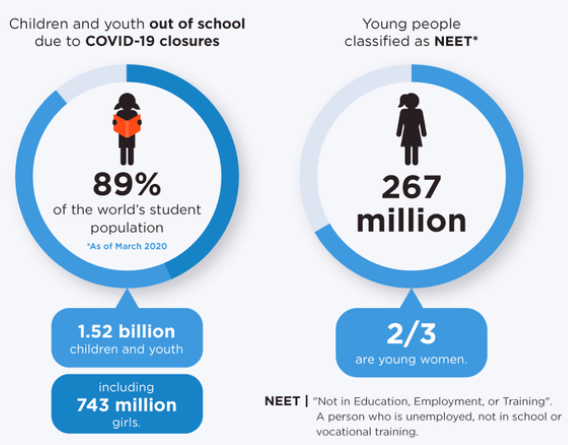

(i) The impact of novel coronavirus hasn’t spared any single sphere of life and no sector has been unaffected.

(ii) Now, six months into the pandemic, not only has there been a colossal loss of life and economic damage the world over, but COVID-19, as it has come to be called, is leaving a lasting impression on education.

(iii) This in turn is bound to have a telling impact on generations to come, forgetting for a second the extent to which the current graduating classes are in a state of limbo(incomplete).

(iv) In a larger perspective it has also raised the spectre(threat) of educational institutions shuttering their doors completely or taking unprecedented steps that have invariably affected jobs and livelihoods.

A Comparison With The West

(i) Shifting gears in an academic setting is not easy whether one is talking about institutions in the developed West or the developing nations.

(ii) Economics has always been a part of academics.

(iii) It is only in the present circumstances that it has become all the more apparent as to how management, especially in private institutions, is going to meet demands on the one hand and availability of resources on the other.

(iv) If one may call this new phenomenon “acadonomics”, it would imply a careful allocation of resources keeping in mind the transient(temporary) nature of the issue of how long it is going to take to come back to the steady state of affairs that it once was.

(v) ‘Acadonomics’ will also involve seeing the economics of moving on to an online mode of the teaching-learning process, whether it is going to be a temporary phenomenon, something of a mix to be offered or a permanent alternative to the current scheme of things that has come to stay for the short and the medium terms.

(vi) The academic choices, or in some instances, luxuries, are not the same for all countries across the world.

(vii) For instance in the United States, long considered as the Mecca of Higher Education, the elite private and state subsidised universities have endowments(funding) that can be used for a range of academic activities — from giving out fellowships to subsidising tuition fees.

(viii) Harvard University, for example, is said to have an endowment of close to $40 billion, and the top 10 have a cushion of anywhere between $10 billion to $40 billion.

(ix) By contrast, private academic institutions in India which are not-for-profit do not have any such buffers; and, none of the institutions in this country possesses big corpuses(collections) from alumni or industry; their survival for the most part is on the annual income that comes from tuition and the assortment of other fees collected.

Private Education

(i) In the way they are set up, private institutions in India are hardly in a position to meet an eventuality such as COVID-19, something that comes by lightning speed and leaves a trail of destruction that would take many, many years to rectify.

(ii) In an educational set-up in India, nothing can be reduced — the norms cannot be lowered nor can the infrastructure be dismantled.

(iii) The status quo(existing state) with respect to fixed costs remains the same, with some marginal(small) adjustments possibly in costs of electricity, water and deferments in salaries.

(iv) For the most part, the fixed and operational costs remain the same, and infrastructure once created cannot be shrunk.

(v) The downside to self-financed institutions is that in the time of the pandemic and loss of jobs, students plead inability to pay the requisite fee (and in many instances, the hostel fee as well) thereby placing additional burden on the management which feels already stretched because of existing commitments that would include paying off interest on the money borrowed for improving infrastructure on their campuses.

Dual Mode Of Learning

(i) The spike in cost for persisting with a dual mode of the teaching-learning process is going to be quite prohibitive for the next few years.

(ii) First, the scaling of operations that would include the dual modes of online and offline is going to be expensive due to a dual mode of educational delivery.

(iii) To rub salt into the wound(increase pain), the new social distancing norms would lead to the enforcement of smaller class sizes, thereby increasing the effective teaching load and multiplicity of efforts.

(iv) Second, the online teaching mode brings with it increased costs of IT infrastructure such as network bandwidth, servers, cloud resources and software licensing fees.

(v) Third, online teaching means new hiring in the IT sector and increased costs due to engagements with Massive Open Online Courses, or MOOCs, and other online platforms.

(vi) Fourth, online teaching means setting up multiple studios and educational technology centres which translate into investments in high technology.

(vii) Fifth, creation of virtual laboratories across all domains of studies and examination centres, etc. would add to the woes in terms of already depleted finances.

(viii) Finally, it is a wrong perception that all faculty members are adept(skillful) in online teaching — style and delivery go far beyond donning a jacket, having adequate personal grooming and rattling off from a teleprompter.

(ix) Therefore, additional funds have to be allocated to train faculty for online teaching.

Possible Reforms

(i) In these difficult times, the onus(responsibility) is on the Centre and State governments to provide soft loans to students to stay with the educational course.

(ii) For professional and non-professional courses, the natural tendency for students would be to opt for online courses as they could cut back and save on hostel, mess and travel costs.

(iii) At the same time students looking at online instruction would be disinclined to pay the same fee charged for offline instruction which means that some institutions may well have to shut down due to their inability to meet costs.

(iv) Therefore, owing to ‘acadonomics’, the consequences can be quite dire(serious) with a potential to cause irreparable and long-term harm to the younger generations of students as well as institutions.

(v) At this point of time it would seem prudent(wise) for the government and regulatory bodies to not interfere in the fee structure, and, for the future, even consider a measure of higher degree of financial autonomy.

(vi) One would agree that in the long run, technology can flatten the cost due to economies of scale, but in a shorter frame of time of three to five years, the cost of education is likely to go up.

Conclusion

(i) It may be an exaggeration to say that in India, education and the financial models are inverted as opposed to many others.

(ii) There is good quality private school education but one that is fairly expensive; but good quality higher education is subsidised in relation to their direct costs.

(iii) While replicating(copying) any western model in India may not be wholly appropriate, it is high time institutions in India are allowed to create coffers or corpuses for a rainy day.

(iv) Or, perhaps, educational institutions could come to be treated like any other corporate body, with an allowable small margin of profit.

(v) The corporate model addresses not just financial sustainability but also a professional governance structure that would entail better accountability and holistic education.

(vi) ‘Acadonomics’ of the future will not only decide the fate of the academic sector in India but also its quality, ranking, research, innovation potential and its collective impact on our country’s economy.

3. TREATING DATA AS COMMONS

GS 2- Important aspects of governance, transparency and accountability

Context

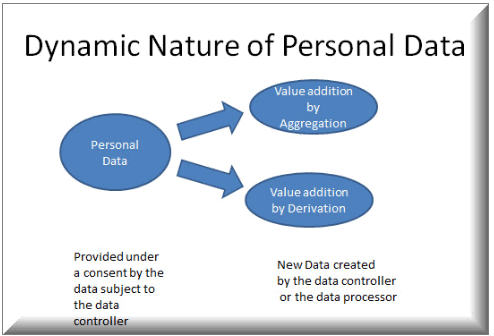

(i) The Gopalakrishnan Committee set up by the government on developing a governance framework for non-personal data recently put out its draft report for public consultation.

(ii) The report’s main purpose is to ensure wide sharing and availability of data in society.

(iii) To ensure that companies share the required data, it was found necessary to develop strong conceptual and legal basis for data-sharing requirements and obligations.

(iv) To understand why data sharing is needed, and its importance to a strong and fair digital economy, we must first recognise the infrastructural nature of data.

(v) Industrial age infrastructure — roads, electricity, etc. — were often publicly owned.

(vi) Even if there was some private role, these were run as closely regulated public utilities.

(vii) The idea was to ensure widespread availability of such infrastructural elements to all, and avoid wasteful duplications. Society’s data have a similar nature for a digital economy.

Digital Vertical Integration

(i) The digital age came with useful digital services that everyone lapped up. Many of these services were free or highly subsidised.

(ii) The infrastructure versus over-the-top services distinction may initially have not been too significant.

(iii) But that difference becomes important as digital corporations begin to dominate all sectors, including important ones such as education and health.

(iv) That very few corporations have vertically integrated all the digital components involved in delivery of any digital service is the reason for their becoming such huge global monopolies.

(v) Seven out of the top 10 companies globally today have a data-centric model.

(vi) Such unsustainable concentration of digital power has a significant geopolitical dimension, with complete domination globally of U.S. and Chinese companies.

(vii) At the national level its deleterious effect is of exploitation of consumers and small economic actors, and of strangulating competition and innovation.

(viii) There are calls worldwide to break up Big Tech; to moderate their monopoly power.

(ix) Their monopoly is best addressed by separating the infrastructural elements of digital service provision from the business of digital service delivery.

(x) There are two key infrastructural components of a digital economy: data and cloud computing. The Gopalakrishnan report and this article focus on the infrastructural element of data.

(xi) Infrastructures are to be equitably provided for all businesses. Data have similar characteristics.

(xii) But today, dominant digital corporations are building exclusive control over any sector’s data as their key business advantage.

(xiii) Start-ups try to ape the same mode. What is needed, however, is to treat data as infrastructure, or ‘commons’, so that data are widely available for all businesses.

(xiv) The digital businesses then shift their key business advantage from exclusive access to data to employing available data for devising digital services for consumers’ benefit.

Reducing Digital Dependence

(i) The Gopalakrishnan committee takes such an infrastructural view of data.

(ii) Data collected from various communities are considered to be ‘owned’ by the relevant community.

(iii) Such ‘community ownership’ means that the data should be shared back with all those who need it in society, whether to develop domestic digital businesses or for producing important digital public goods.

(iv) With a robust domestic data/AI industry, dependence on U.S. and Chinese companies will reduce.

(v) It is for these purposes that the Gopalakrishnan committee proposes the concept of ‘community data’.

(vi) Only the data collected from non-privately owned sources, from society or community sources, have to be shared when requested for.

(vii) Data from privately owned sources remain private. Since a community requires a legally recognisable body to articulate its data ownership claim, the committee introduces the concept of community trustees that could be various bodies representative of the community.

(viii) Data collectors are considered as data custodians that will use and secure data as per the best interests of the community concerned.

(ix) Data trusts are data infrastructures that will enable data sharing, sector-wise, or across sectors, and which can be run by various kinds of third-party bodies.

(x) The committee recommends a new legislation, because ensuring and enforcing data sharing will require sufficient legal backing.

(xi) A Non-Personal Data Authority is also envisaged to enable and regulate all the envisaged data-sharing activities.

Conclusion

(i) India is the first country to come up with a comprehensive framework in this area.

(ii) Starting early in this important digital policy and governance area may just provide a formidable first mover advantage for India to acquire its rightful place in the digital world.

|

21 videos|562 docs|160 tests

|

FAQs on The Hindu Editorial Analysis- 2nd Sept, 2020 - Additional Study Material for UPSC

| 1. What is the significance of analyzing The Hindu editorials for UPSC preparation? |  |

| 2. How can The Hindu editorials be used effectively for UPSC exam preparation? |  |

| 3. How can one improve their comprehension skills while reading The Hindu editorials for UPSC preparation? |  |

| 4. What are some common challenges faced while analyzing The Hindu editorials for UPSC preparation? |  |

| 5. Are there any additional resources or strategies that can complement the analysis of The Hindu editorials for UPSC preparation? |  |