The Hindu Editorial Analysis- 12th Sept, 2020 | Additional Study Material for UPSC PDF Download

1. GLIMMER OF HOPE: ON INDIA-CHINA FIVE-POINT CONSENSUS-

GS 3- Security challenges and their management in border areas

Context

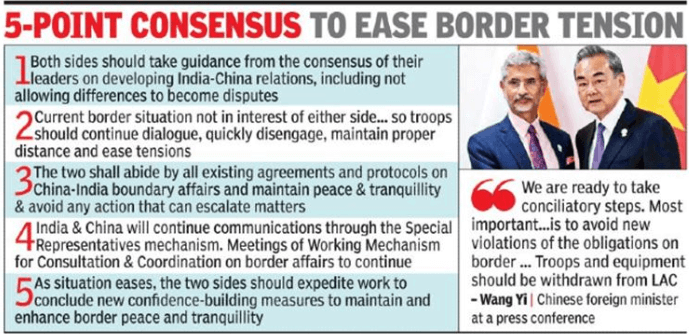

(i) The “five-point consensus” reached by the Foreign Ministers of India and China in Moscow on Thursday provides a glimmer(ray) of hope of a diplomatic solution, while thousands of troops from both countries remain deployed along the border.

(ii) It is, however, only a glimmer.

Descalating Tensions

(i) Each point, outlined in a joint statement, has been affirmed previously by the two neighbours, both in past boundary agreements and in talks held since June that have failed to de-escalate tensions.

(ii) The LAC remains tense, facing its worst crisis since 1962.

(iii) Both sides have agreed to take guidance from previous understandings, including on “not allowing differences to become disputes”, a formulation of 2017 that has not lived up to its promise.

(iv) They agreed the current situation suits neither side, troops should quickly disengage, maintain proper distance, and ease tensions.

(v) Both sides said they would abide(follow) by all existing agreements, continue dialogue, and expedite work on finding confidence building measures to maintain peace.

Status Quo Ante Demand

(i) At the same time, stark differences remain, including on the key question of whether both sides will return to the status quo ante(previous existing affair) prior to China’s transgressions(violations).

(ii) The issuing of the joint statement was somewhat unusually accompanied by separate press statements, which struck discordant(disagreement) notes on key issues.

(iii) India stressed that peace on the boundary was essential for ties, and that recent incidents had impacted the broader relationship.

(iv) The Chinese statement, on the other hand, sought to emphasise the importance of “moving the relationship in the right direction” and to put the border “in a proper context”.

(v) China’s statement also quoted India’s Foreign Minister as saying India believed China’s policy toward India had not changed and that it did not consider relations to be dependent on the settlement of the boundary question.

(vi) This characterisation of India’s stand was a sharp contrast from Delhi’s recent public statements, which have emphasised border peace as a prerequisite(precondition) to taking forward the broader relationship.

(vii) Moreover, a day before the talks, China’s official news agency issued a commentary placing the onus(responsibility) entirely on India to defuse tensions.

(viii) China accused India of “reckless provocations(inciting)”, telling India “to learn from history”, and reiterating(repeating) that China “will not lose an inch of territory”.

(ix) It is welcome that India and China have finally found something to agree on. Thursday’s consensus, however, is only the first step of a long road ahead.

(x) The continuing rounds of talks should be aimed sincerely at disengagement, and not at presenting a veneer(cover) of diplomatic engagement even while China strengthens its hold along the LAC.

(xi) India will need to verify before it can trust each of China’s steps from now on.

Conclusion

India and China have taken the first step to begin real disengagement at the border.

2. PUSHBACK: ON U.S. REVOKING VISA TO CHINESE STUDENTS-

GS 2- Effect of policies and politics of developed and developing countries on India’s interests, Indian diaspora

Context

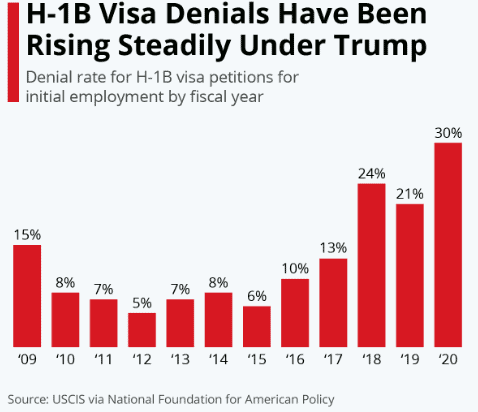

The Trump administration has revoked(cancelled) visas for more than 1,000 Chinese citizens, mainly students and researchers, deemed to be risks to national security owing to their alleged connections to Chinese military establishments and concern over industrial espionage(spying).

Policy Action

(i) The White House’s latest policy action has been housed under Mr. Trump’s May 29 announcement responding to China’s curbs on democracy in Hong Kong.

(ii) Among the reasons stated was the intention to block the entry of persons associated with slave labour, thought to be a reference to alleged rights violations of China’s Uighur Muslims.

(iii) According to the Department of Homeland Security, the revocation is also targeting those who might engage in unjust business practices or attempt to steal coronavirus research, and, more broadly, abuse their student visa status to exploit the intellectual property of academia.

(iv) This visa policy comes after measures that have tightened the screws on the U.S. immigration system, including halting the issuance of green cards and skilled worker visas and challenging the issuance of student visas for college programmes that have migrated entirely to online mode due to the pandemic.

(v) However, in the prior cases of visa issuance bans, the nationals of a single country were not targeted in the way that Chinese citizens have been under this week’s visa revocation.

High Handed Response

(i) The deeper context of this spat is the cycle of hostile tit-for-tat exchanges between Washington and Beijing, principally tariff wars in the realm of trade, but extending to human rights and China’s COVID-19 response.

(ii) On the one hand the Trump administration might have overreached in this broad-brush policy, perhaps sweeping up innocent researchers with no more than nominal association with a government-affiliated academic entity in China.

(iii) However, it is more than likely, given the successive industrial espionage incidents that have been prosecuted by the U.S., that potential spies or saboteurs(destroyers) are facing removal proceedings too.

(iv) Ultimately, countries such as China and Russia, which have arguably sought to interfere in the U.S.’s domestic affairs, could be facing a blowback.

(v) However, given the pressure-cooker conditions in U.S. politics due to an imminent(immediate) election, there is a strong likelihood of a heavy-handed response to any further suspicions of foreign interference, especially because such a response would be of considerable campaign value to the incumbent.

(vi) If Mr. Trump remains in the Oval Office, he will doubtless persist with his friendly approach toward Moscow, while seeking to keep Beijing on the back foot.

(vii) The policies of his Democratic rival, Joe Biden, are expected to be the reverse to an extent, although Chinese President Xi Jinping would be unwise to anticipate a quick thaw(peace) in frosty bilateral ties in that case too.

(viii) Either way, China’s economic aggression will continue to face pushback from a wounded and angry America.

Conclusion:

Chinese students are caught in a broad-brush U.S. response to espionage(spying).

3. A GAME OF CHESS IN THE HIMALAYAS-

GS 2- India and its neighborhood- relations

Incidents From Past

(i) The Great Leap Forward (Second Five Year Plan) of the People's Republic of China (PRC) was an economic and social campaign led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1958 to 1962. Chairman Mao Zedong launched the campaign to reconstruct the country from an agrarian economy into a communist society through the formation of people's communes. Mao decreed increased efforts to multiply grain yields and bring industry to the countryside. Local officials were fearful of Anti-Rightist Campaigns and competed to fulfill or over-fulfill quotas based on Mao's exaggerated claims, collecting "surpluses" that in fact did not exist and leaving farmers to starve. Higher officials did not dare to report the economic disaster caused by these policies, and national officials, blaming bad weather for the decline in food output, took little or no action. The Great Leap resulted in tens of millions of deaths, with estimates ranging between 18 million and 45 million deaths, making the Great Chinese Famine the largest in human history.

(ii) Before the 1962 Sino-Indian War, the Forward Policy had Nehru identify a set of tactical strategies theories designed with the ultimate goal of effectively forcing the Chinese from territory that the Indian government had claimed. The doctrine was based on a theory that China would not likely attack if India began to occupy territory that China considered its own. Part of Its thinking was partly based on the fact that China had nany external problems in the early months of 1962, especially with the Taiwan Strait Crisis. Also, the Chinese leaders had insisted they did not wish for war.

Context

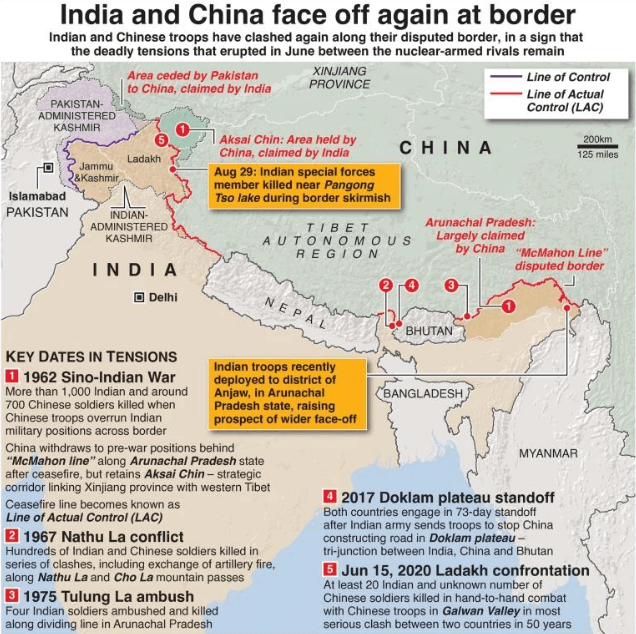

(i) With the tensions along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) refusing to die down, despite the marathon military and diplomatic-level talks, the obvious question that stares at every stakeholder is this: is 2020 another 1962?

(ii) While the future is uncertain, the present is undoubtedly tense.

(iii) As stated by India’s External Affairs Minister, S. Jaishankar, this is “surely the most serious situation” along the India-China border “after 1962”.

(iv) The parallels are hard to ignore.

(v) In August 1959, after the first border clash between Indian and Chinese troops in Longju, in the eastern sector, China said Indian troops had crossed the McMahon Line and opened fire, and the Chinese border guards had fired back.

(vi) The next day, New Delhi protested against the Chinese statement, saying it was Chinese troops that had moved into Indian territory and opened fire.

(vii) Sixty-one years later, the statements issued by India and China after the border clashes are eerily similar. Both sides accuse each other of transgressing(violating) across the LAC.

(viii) Both sides accuse each other of opening fire. Both sides blame each other for the current standoff.

The Trigger

(i) What led to the war? To understand the current tensions, one has to go back in history.

(ii) When the Longju incident happened, not many in India might have thought the border tensions would lead to a full-scale Chinese invasion.

(iii) Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Defence Minister V.K. Krishna Menon were absolutely certain that China would not attack India. Nehru had betted big on India’s friendship with China.

(iv) He saw both countries as victims of imperialism and the natural leaders of Asia.

(v) The realist in Nehru believed that peace on India’s northern border was an imperative(need) for the newly-born republic’s rise and material development.

(vi) So in the 1950s, Nehru continued to defend China in international fora. India accepted Chinese sovereignty over Tibet and signed an agreement with Peking over trade with Tibet.

(vii) But what Nehru hoped in return for India’s friendship was China respecting its bequeathed(left) boundaries — the McMahon Line in the east and the frontier (based on the 1842 Tibet-Kashmir agreement) in the west. Nehru was wrong.

(viii) The first setback to this position was the Longju incident. Within two months, an Indian police patrol team in Kongla Pass in Ladakh came under Chinese attack. This was a wake-up call for Nehru.

(ix) He asked Chinese troops to withdraw from Longju in return for an assurance from India not to reoccupy the area and proposed that both sides pull back from the disputed Aksai Chin, where China had already built (unilaterally) a strategic highway.

(x) China rejected this proposal and made a counter offer — to recognise the McMahon Line in the east in return for India’s recognition of Chinese sovereignty over Aksai Chin.

(xi) Nehru, having checked the historical maps, documents, including revenue records and land surveys, which he got from the India Office in London, rejected the Chinese offer because he thought it would mean India abandoning(giving up) its legitimate claims over Aksai Chin.

(xii) After the collapse of the Nehru-Zhou Enlai [Chou en Lai] talks in 1960 in Delhi, tensions escalated fast. China intensified patrolling(observing) along the border.

(xiii) In November 1961, Nehru ordered his Forward Policy as part of which India set up patrol posts along the LAC, which was seen as a provocation in Beijing. In October 1962, Mao Zedong ordered the invasion.

The Parallels

(i) The situation today is not exactly the same as 1962. Back then, the Tibet factor was looming over India-China ties.

(ii) As soon as the Dalai Lama took refuge in India, Chinese leaders, including Deng Xiaoping, had threatened “to settle accounts” with the Indians “when time comes”.

(iii) China also feared that India was providing help to Tibetan rebels, after the 1959 rebellion.

(iv) Today, both sides have managed to sidestep the Tibetan question in their bilateral engagement.

(v) And unlike in 1962, when India was not politically and militarily prepared for a war with China, today’s conflict is between two nuclear powers.

(vi) But the problem is this; while the overall situation is different, the border conflict looks similar to what it was in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The boundary has still not been delimited and demarcated.

(vii) China has not recognised the McMahon Line and India has not accepted China’s control over Aksai Chin.

(viii) Despite the volatile situation, an uneasy truce prevailed on the border at least since 1975 and both sides have made improvements in ties since Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s visit to Beijing in 1988.

(ix) This period of truce allowed both countries to focus on their development. But that truce(ceasefire) has now been disrupted with China first moving to block Indian patrolling in the Finger area of Pangong Tso and the Galwan Valley in eastern Ladakh during the summer.

(x) India then made a forward move on the southern banks of Pangong Tso last month, similar to Nehru’s Forward Policy in 1961, taking over the heights of the Kailash Range.

(xi) When Nehru ordered the Forward Policy, his aim was to secure the vast border and prevent further incursions. He never thought China would attack.

(xii) Now, despite the experience of 1962, India appears to be taking a calculated risk by making forward movements.

(xiii) This led to the opening of fire in the region, for the first time in 45 years. So, practically, the border situation is back to what it was in 1961.

Strategic Dominance

(i) In the run-up to the 1962 war, Mao had taken a “unity and struggle” policy towards India.

(ii) This meant, laying emphasis(focus) on unity with India on mutually agreeable matters while continuing the struggle over the border issue.

(iii) Nehru failed to understand the gravity of this approach. He first saw only unity, and, after the Longju and Kongla clashes, he saw only struggle.

(iv) China, on the other side, consistently played what game theorists call the game of “strategic dominance”— the strategy which would yield positive outcomes, irrespective of the strategies of the rival player.

(v) Back then, China saw itself as the most powerful force in Asia. Japan had been devastated by the war.

(vi) The British withdrawal and the partition of the subcontinent had changed the geopolitical balance in the continent.

(vii) Mao was facing challenges to his leadership within the party after the disastrous Great Leap Forward.

(viii) Globally, there were cracks in the Sino-Soviet alliance, especially after the Soviet intervention in Hungary.

(ix) When it set the ball of border tensions rolling, it knew that the ultimate risk would be a limited war and it was ready to take that risk because even in the event of a war, China calculated that it could retain its strategic dominance. And it did so in 1962.

Conclusion

(i) The Chinese strategy today is not very different from that of the 1960s.

(ii) Now, China considers that it has arrived on the global stage as a military and economic superpower.

(iii) The COVID-19 outbreak has battered its economy, but it is recovering fast. India, on the other side, is in a prisoner’s dilemma(confusion) on how to tackle China.

(iv) India is a big, rising power, but is going through short-term challenges.

(v) Its economy is weak. Its geopolitical standing in the neighbourhood is not in its best days.

(vi) Unlike in the 1960s, when Nehru’s non-alignment was blamed for Chinese aggression, today’s India has cautiously moved toward the United States.

(vii) But still, there is no guarantee that it would deter(prevent) China or if the U.S. would come to India’s help in the event of a war.

(viii) A combination of all these factors might have led China to believe that it can play the game of strategic dominance once again.

(ix) If India plays it on China’s terms, there will be war.

(x) The question is whether it should walk into the trap laid in the Himalayas, or learn from the experiences of 1962.

|

21 videos|562 docs|160 tests

|

FAQs on The Hindu Editorial Analysis- 12th Sept, 2020 - Additional Study Material for UPSC

| 1. What is the significance of the UPSC exam? |  |

| 2. How can I prepare for the UPSC exam effectively? |  |

| 3. What is the eligibility criteria for appearing in the UPSC exam? |  |

| 4. Are there any age relaxations for candidates belonging to reserved categories in the UPSC exam? |  |

| 5. What are the stages involved in the UPSC exam selection process? |  |