The Hindu Editorial Analysis- 3rd November, 2020 | Additional Study Material for UPSC PDF Download

1. BACK TO SCHOOL-

GS 2- Issues relating to development and management of Social Sector/Services relating to Education

Context

(i) The most significant aspect of continued unlocking of public activity during the COVID-19 pandemic is the decision of many States to reopen schools in November.

(ii) While some, such as Andhra Pradesh and Assam, have allowed pupils back on campus from November 2, many others are waiting until Deepavali to resume classes.

Additional Vigilance

(i) Attendance at schools remains voluntary, since the Centre’s guidelines, which now extend until the end of November, specify that parents can decide what their wards(children) should do.

(ii) Existing regulations allow research scholars and students who have to take up practical work to resume from October 15, but colleges remain understandably cautious and want to adopt a staggered approach to reopening.

(iii) India’s revitalised public sphere outside containment zones, with shops and restaurants open, and buses and urban trains on stream, is set to widen its scope as cinemas also open at half capacity.

(iv) These activities will restore the sinews(structure) of the economy, but they come with the risk of exposing more people to the coronavirus.

(v) At the end of several fatiguing(tiredness) months of restrictions, the belief that India has crossed peak infections and reduced its transmission rate could well prompt citizens to become lax(ease) about safe behaviour like distancing norms.

(vi) This could pose an unprecedented(unparallel) risk, since children who are believed to be less affected by the infection could bring the virus home to vulnerable individuals, a phenomenon experienced after reopening schools in Israel.

(vii) Minimising negative impacts during the unlock and pre-vaccine phase, therefore, requires unwavering adherence to safety protocols, and additional vigilance(care) on the part of State health authorities who must monitor the situation in educational institutions.

Mixed Reactions

(i) Globally, reopening of schools has elicited(brought) mixed reactions, but governments have deferred to the learning needs of children in Europe where lockdowns have been reimposed due to a fresh wave of cases.

(ii) In any case, data published in August show that children represented less than 5% of all infections in 27 European countries.

(iii) Teachers’ unions in Britain are calling for limited classes to help disadvantaged children and those with parental commitments;

(a) public schools in many U.S. States remain closed while some private institutions have reopened;

(b) France is asking even small children to wear masks along with teachers.

(iv) The consensus is to prevent crowding, mandate masks, and allow natural air to ventilate rooms. Such precautions have universal applicability as preventive measures.

(v) A reopening will revive the economy, but it need not impose a deadly price in the form of avoidable and invisible deaths among the elderly and the vulnerable.

Conclusion

Reopening will prevent a washout year for students but the pandemic is not past.

2. END OF THE TUNNEL?

GS 3- Indian Economy and issues relating to planning, mobilization of resources, growth, development and employment

Context

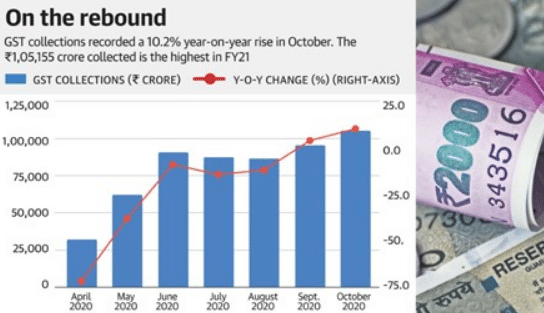

(i) Over ₹1.05 lakh crore has been collected from the Goods and Services Tax in October, the highest monthly revenue from the indirect tax since February 2020.

(ii) This marks the second successive month of a year-on-year uptick in the GST kitty — the 10.25% rise in October was preceded by a 4% increase in September.

Economy Under Recovery

(i) Coming on the back of six successive months of contraction in GST revenues beginning March when the lockdown was imposed, this two-month trend clearly signifies a recovery is underway in the economy, the government has claimed.

(ii) October’s revenues broadly pertain to economic activity that occurred in September, a month in which significant improvements were recorded in a range of high-frequency indicators, including exports and the purchasing managers’ index (PMI) for manufacturing.

(iii) Only a part of that can be explained by the base effect — September 2019 had seen a dip in several indicators.

(iv) Indeed, the wider unlocking of the economy in September when public transport restrictions were lifted and several sectors were allowed to operate with fewer curbs, helped.

(v) After the 23.9% collapse for the economy in the first quarter of 2020-21, the sense of relief from a string of positive numbers isn’t misplaced.

(vi) The few signs that have come in about October’s economic performance suggest GST revenues could remain healthy in November too.

(vii) The manufacturing PMI for October, released on Monday, has risen even higher, indicating large firms scaled up production further.

(viii) India’s largest auto makers have clocked record sales in October, which incidentally should prop up(increase) the GST cess collections used to compensate States — a federal flashpoint this year.

Reservations About The Numbers

(i) Yet, any prognosis(prediction) of a full-fledged economic recovery could still prove to be premature and illusory.

(ii) Economists have reservations about reading too much into the September-October data as a sustainable trend, for it partly represents pent-up demand brewing over the months of lockdown finding expression, and partly India’s fabled festive season effect.

(iii) North Block mandarins(officials) recently critiqued these ‘experts’ for their changing opinions, swinging from a doomsday(dangerous) scenario in June to a cynical ‘pent-up demand’ surmise(guess) when economic indicators improve.

(iv) Talking up the economy is perhaps a necessary policy device at times, but equally critical is a realistic assessment of ground realities so as to prepare better for what lies ahead.

(v) One such parameter that needs attention is employment.

(vi) The government has not ruled out more stimulus measures in the coming months.

(vii) Much depends on the sensitivity of its evolving worldview, be it about the pandemic’s spread and control, or the most challenged sectors in the economy that still need support.

Conclusion

The welcome pick-up in GST revenues may not yet signal a sustainable economic recovery.

3. THE NUTRITION FALLOUT OF SCHOOL CLOSURES-

GS 2- Issues relating to poverty and hunger

Context

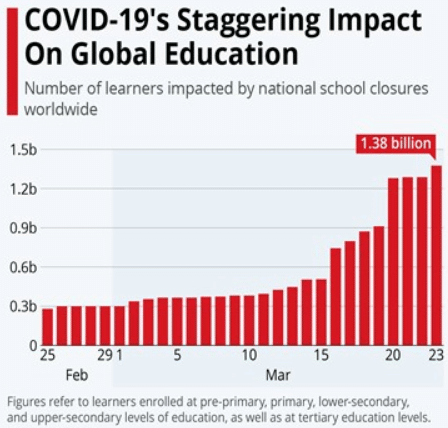

(i) As many as 116 million is the number of children we are looking at when we consider the indefinite school closure in India.

(ii) The largest school-feeding programme in the world, that has undoubtedly played an extremely significant role in increasing nutrition and learning among schoolgoing children, has been one of the casualties(victims) of the COVID-19 pandemic.

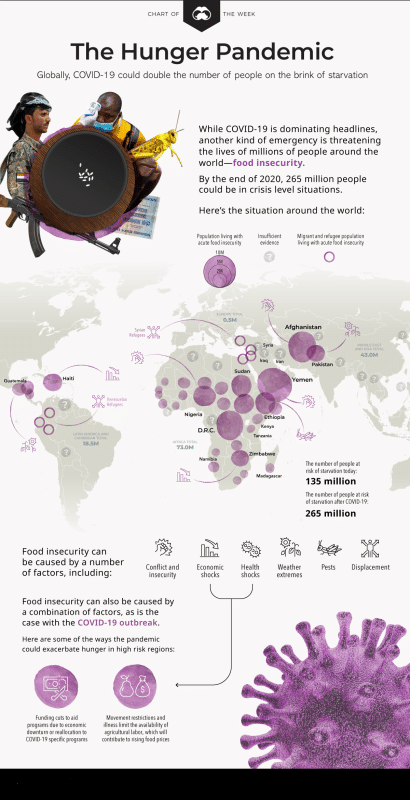

(iii) The report of The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020, released by the Food and Agriculture Organization in partnership with other UN organisations, painted a worrying picture.

(iv) A real-time monitoring tool estimated that as of April 2020, the peak of school closures, 369 million children globally were losing out on school meals, a bulk of whom were in India.

Pressing Issue

(i) The recent Global Hunger Index (GHI) report for 2020 ranks India at 94 out of 107 countries and in the category ‘serious’, behind our neighbours Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal.

(ii) The index is a combination of indicators of undernutrition in the population and wasting, stunting, and mortality in children below five years of age.

(iii) We are already far out in terms of achieving the ‘Zero Hunger’ goal, and in the absence of urgent measures to address the problem, the situation will only worsen.

(iv) A report by the International Labour Organization and the UNICEF, on COVID-19 and child labour, cautions that unless school services and social security are universally strengthened, there is a risk that some children may not even return to schools when they reopen.

(v) A mid-day meal in India should provide 450 Kcal of energy, a minimum of 12 grams of proteins, including adequate quantities of micronutrients like iron, folic acid, Vitamin-A, etc., according to the mid-day meal scheme (MDMS) guidelines.

(vi) This is approximately one-third of the nutritional requirement of the child, with all school-going children from classes I to VIII in government and government-aided schools being eligible.

(vii) However, many research reports, and even the Joint Review Mission of MDMS, 2015-16 noted that many children reach school on an empty stomach, making the school’s mid-day meal a major source of nutrition for children, particularly those from vulnerable communities.

Difficulty In Implementing

(i) In orders in March and April 2020, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and closure of schools, the Government of India announced that the usual hot-cooked mid-day meal or an equivalent food security allowance/dry ration would be provided to all eligible school-going children even during vacation, to ensure that their immunity and nutrition is not compromised.

(ii) Nearly three months into this decision, States were still struggling to implement this.

(iii) According to the Food Corporation of India’s (FCI) food grain bulletin, the off take of grains under MDMS from FCI during April and May, 2020 was 221.312 thousand tonnes.

(iv) This was 60 thousand tonnes, or 22%, lower than the corresponding offtake during April and May, 2019 (281.932 thousand tonnes).

(v) There were 23 States and Union Territories that reported a decline in the grain off take from FCI in April-May 2020, compared with corresponding months in 2019.

(vi) The State of Bihar, for instance, which lifted 44.585 thousand tonnes in April and May 2019, had no offtake during these two months in 2020.

Irregular Supply

(i) Data and media reports indicate that dry ration distributions in lieu(place) of school meals are irregular.

(ii) Further, since the distribution of dry ration started only in late May, a few experts — like Dipa Sinha of Ambedkar University — are calling for immediate distribution of the April quota, to which the children are entitled.

(iii) The other worrying angle is the fact that there are reports of children engaging in labour to supplement the fall in family incomes in vulnerable households.

(iv) In July this year, the Madras High Court also took cognizance(aware) of the issue and asked the Tamil Nadu government to respond on the subject of how, with schools closed, the nutritional needs of children were being fulfilled.

(v) Serving hot meals, at the children’s homes or even at the centre, may have challenges in the present scenario.

(vi) Even States like Tamil Nadu, with a relatively good infrastructure for the MDMS, are unable to serve the mandated ‘hot cooked meal’ during the lockdown.

Innovative Strategies

(i) Local smallholder farmers’ involvement in school feeding is suggested by experts, such as Basanta Kumar Kar, who has been at the helm(top) of many nutrition initiatives.

(ii) He suggests a livelihood model that links local smallholder farmers with the mid-day meal system for the supply of cereals, vegetables, and eggs, while meeting protein and hidden hunger needs, which could diversify production and farming systems, transform rural livelihoods and the local economy, and fulfill the ‘Atmanirbhar Poshan’ (nutritional self-sufficiency) agenda.

(iii) The COVID-19 crisis has also brought home the need for such decentralised models and local supply chains.

(iv) There are also new initiatives such as the School Nutrition (Kitchen) Garden under MDMS to provide fresh vegetables for mid-day meals.

(v) Besides ensuring these are functional, hot meals can be provided to eligible children with a plan to prepare and distribute the meal in the school mid-day meal centre.

(vi) This is similar to free urban canteens or community kitchens for the elderly and others in distress in States like Odisha. Also, adequate awareness about of the availability of the scheme is needed.

(vii) Thirdly, locally produced vegetables and fruits may be added to the MDMS, also providing an income to local farmers.

(viii) Besides, distribution of eggs where feasible (and where a State provision is already there) can be carried out.

(ix) Most of all, the missed mid-day meal entitlement for April may be provided to children as dry ration with retrospective(backdated) effect.

Conclusion

(i) Across the country and the world, innovative learning methods are being adopted to ensure children’s education outcomes.

(ii) With continuing uncertainty regarding the reopening of schools, innovation is similarly required to ensure that not just food, but nutrition is delivered regularly to millions of children.

|

21 videos|562 docs|160 tests

|

FAQs on The Hindu Editorial Analysis- 3rd November, 2020 - Additional Study Material for UPSC

| 1. What is the significance of the Hindu Editorial Analysis for UPSC exam preparation? |  |

| 2. How can the Hindu Editorial Analysis help in improving current affairs knowledge? |  |

| 3. Does the Hindu Editorial Analysis provide a balanced perspective on different topics? |  |

| 4. How can one use the Hindu Editorial Analysis to improve their answer writing skills for the UPSC exam? |  |

| 5. Is it necessary to read the Hindu newspaper along with the Editorial Analysis for UPSC exam preparation? |  |