Sexual Reproduction in Flowering Plants Chapter Notes | Biology Class 12 - NEET PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| What is a Flower? |

|

| Pre-fertilisation: Structures and Events |

|

| Double Fertilisation |

|

| Post Fertilisation: Structure and Events |

|

| Apomixis |

|

| Polyembryony |

|

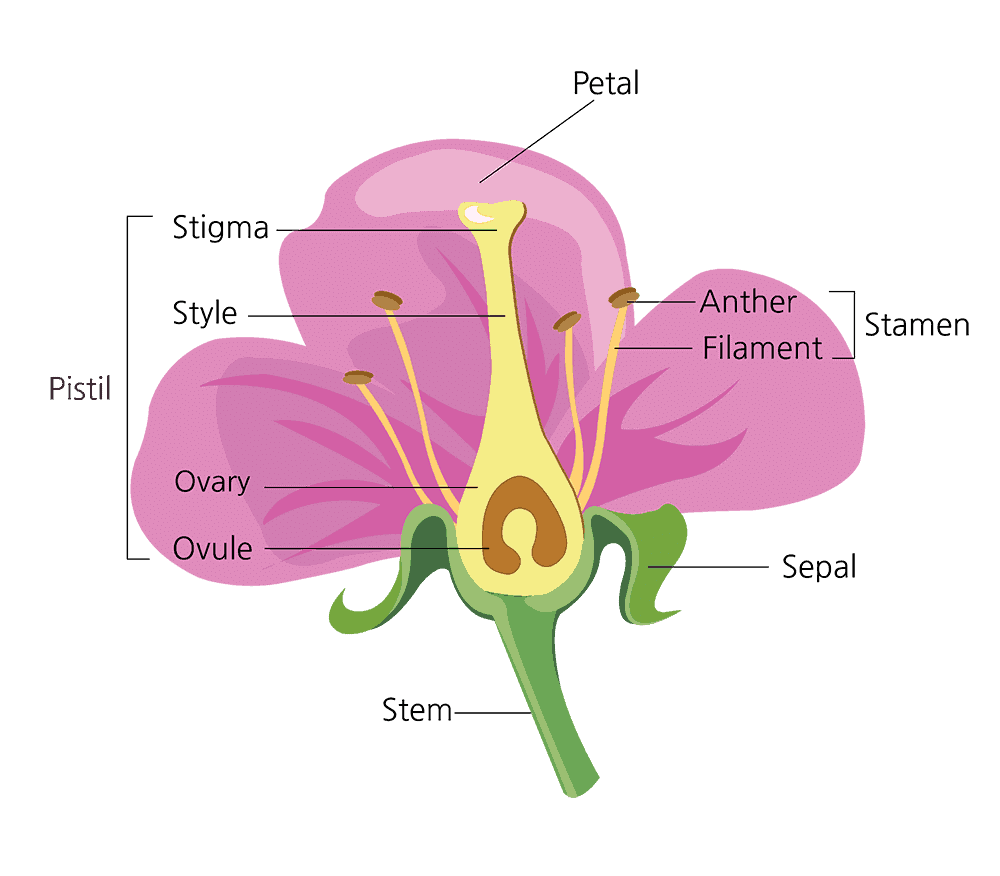

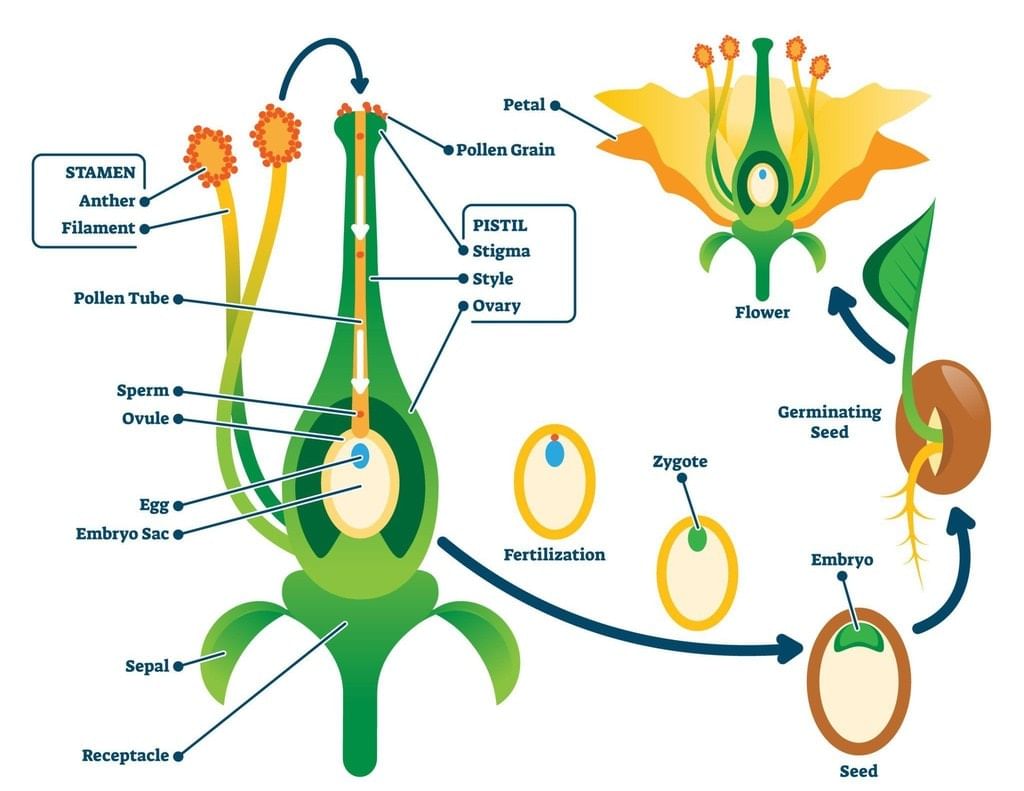

What is a Flower?

A flower is the reproductive structure of a flowering plant (angiosperm) that typically consists of various parts such as petals, sepals, stamens, and pistils. It is responsible for the plant's sexual reproduction, as it produces seeds through the process of pollination and fertilization. Flowers come in various shapes, sizes, and colors, and they often emit fragrances and nectar to attract pollinators like insects, birds, or the wind.

Parts of Flower

Structure of Flower

Structure of Flower

A flower comprises the following parts:

(A) Accessory whorls

(i) Calyx: It is the outermost whorl of a flower. It comprises units called sepals. In the bud stage, calyx encloses the rest of the flower. They usually exhibit green colouration, at some other instances, they may be a colour like petals. This state of Calyx is termed as petaloid. Calyx can either be prominent or absent.

(ii) Corolla: It consists of many numbers of petals and it is the second whorl of the flower. These petals are sometimes fragrant. They are coloured, thin and soft that would help in the process of pollination as they would attract animals and insects.

(B) Reproductive whorls

(i) Androecium:- male reproductive whorl , smallest unit:- stamen

(ii) Gynoecium:- female reproductive whorl, smallest unit:- carpel/ pistil

Pre-fertilisation: Structures and Events

Before the actual appearance of a flower on a plant, the decision for flowering has already been made. This process triggers various hormonal and structural changes that lead to the formation and development of the floral primordium. Inflorescences, which eventually bear floral buds and flowers, are produced. Within the flower, the male and female reproductive structures, known as the androecium and gynoecium, respectively, undergo differentiation and development. The androecium comprises a whorl of stamens, which constitute the male reproductive organs, while the gynoecium represents the female reproductive organs.

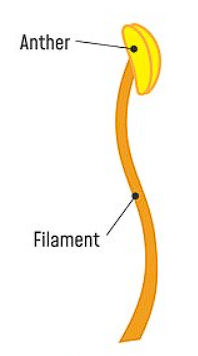

Stamen, Microsporangium and Pollen Grain

Stamen: These are the male part of a flower. Many stamens are collectively known as the androecium. They are structurally divided into two parts:

Structure of Stamen

Structure of Stamen

- Filament: the part that is long and slender and attached the anther to the flower. The base of the filament is connected to the thalamus or the petal of the flower. Different types of flowers have varying numbers and lengths of stamens.

- Anthers: It is the head of the stamen and is responsible for producing the pollen which is transferred to the pistil or female parts of the same or another flower to bring about fertilization.

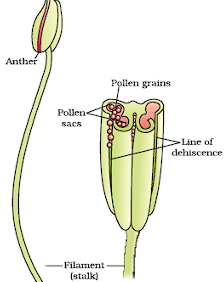

The structure of anther:

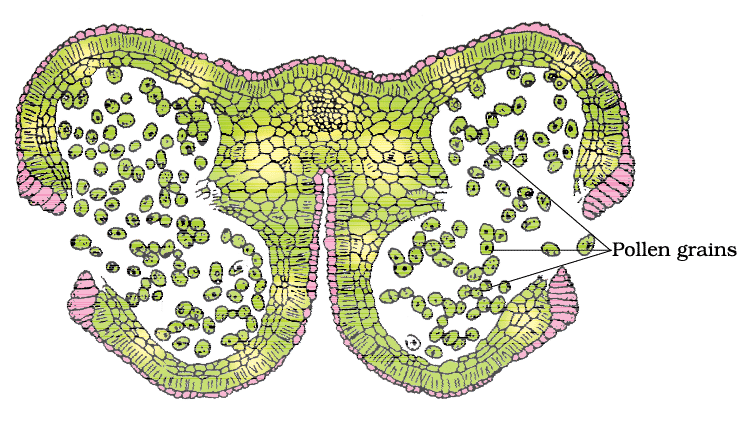

- A typical angiosperm anther is bilobed, with each lobe having two theca, making them dithecous.

- A longitudinal groove often runs lengthwise, separating the theca.

- The anther is a four-sided (tetragonal) structure consisting of four microsporangia located at the corners, two in each lobe.

- The microsporangiadevelop into pollen sacs that extend longitudinally through the length of an anther and are packed with pollen grains.

Microsporangium

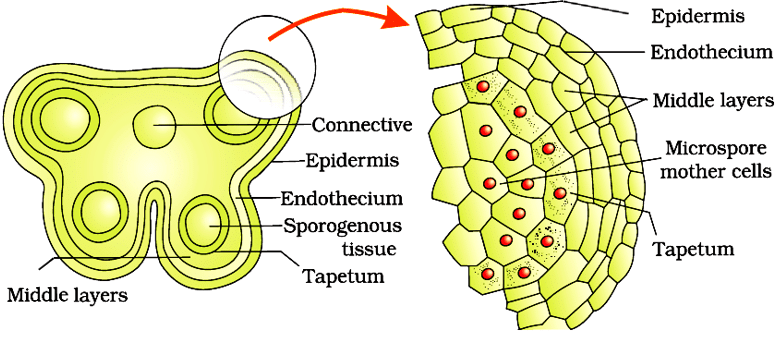

Microsporangia consist of a typical microsporangium has a near-circular outline. It is enclosed by four wall layers - epidermis, endothecium, middle layers, and the tapetum.

Enlarged view of one microsporangium

Enlarged view of one microsporangium

A mature dehisced anther

A mature dehisced anther

- The four wall layers perform different functions.

- Epidermis, endothecium and middle layers protect the microsporangium and aid in its dehiscence to release pollen.

- The tapetum is the innermost layer and nourishes the developing pollen grains.

- Tapetal cells have dense cytoplasm and usually more than one nucleus. They could become bi-nucleate in the following ways:

- Nuclear division without cytokinesis

- Fusion of two adjacent nuclei

- When the anther is young, the sporogenous tissue, a group of compactly arranged homogenous cells, occupies the centre of each microsporangium.

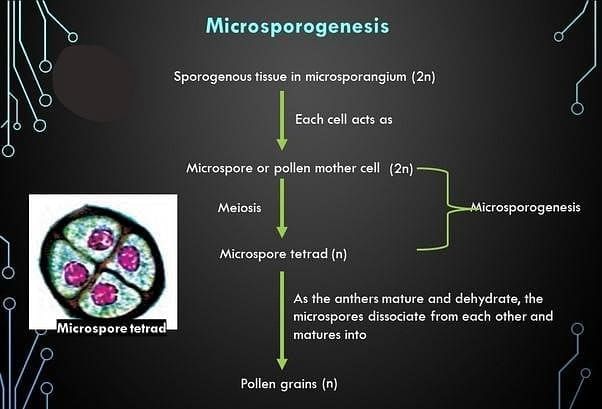

Microsporogenesis

- As the anther develops, cells of the sporogenous tissue undergo meiotic divisions to form microspore tetrads.

- Each cell of the sporogenous tissue is capable of giving rise to a microspore tetrad.

- The process of forming microspores from a pollen mother cell through meiosis is microsporogenesis.

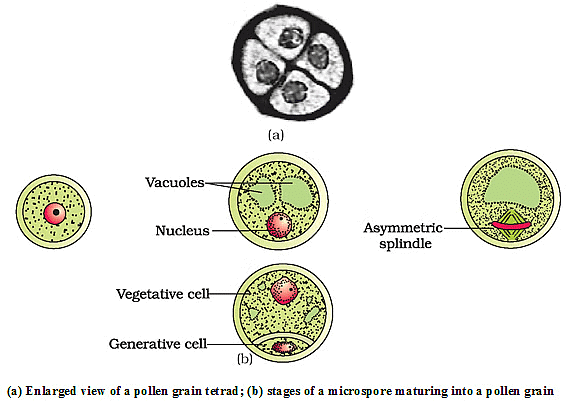

- As microspores are formed, they are arranged in a cluster of four cells - the microspore tetrad.

- As anthers mature and dehydrate, microspores dissociate and develop into pollen grains.

- Several thousand microspores or pollen grains are formed inside each microsporangium and released with anther dehiscence.

Pollen Grain

Pollen grains, also known as male gametophytes, play a crucial role in plant reproduction.

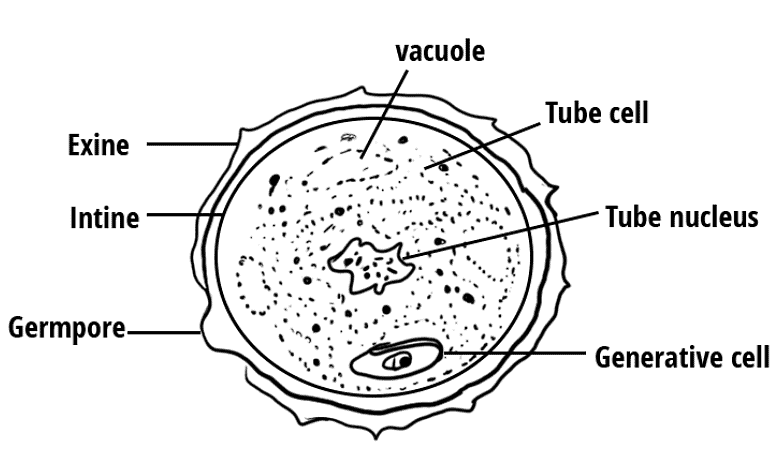

Structure of Pollen Grain

Structure of Pollen Grain

Structure of pollen grains :

Pollen grains are spherical in shape and measure between 25-50 micrometers in diameter. The outer layer of the pollen grain is called the exine, which is made up of a hard and resistant material called sporopollenin.

- Sporopollenin is one of the most resistant organic materials known.

- Sporopollenin can withstand high temperatures and strong acids and alkalis.

- No enzyme that degrades sporopollenin is currently known.

- The exine has prominent apertures called germ pores where sporopollenin is absent.

- The pollen grains are well-preserved as fossils because of the presence of sporopollenin.

- The inner wall of the pollen grain is called the intine, which is a thin and continuous layer made up of cellulose and pectin.

- The cytoplasm of pollen grain is surrounded by a plasma membrane.

- When the pollen grain is mature, it contains two cells - the vegetative cell and generative cell.

- The vegetative cell of the pollen grain is responsible for nourishing the generative cell and guiding it towards the female gametophyte.

- In over 60% of angiosperms, pollen grains are shed at the 2-celled stage. In the remaining species, the generative cell divides mitotically to give rise to the two male gametes before pollen grains are shed (3-celled stage).

Scanning electron micrographs of a few pollen grains

Scanning electron micrographs of a few pollen grains

Variability and Viability of Pollen Grains :

- The period for which pollen grains remain viable is highly variable and depends on the prevailing temperature and humidity.

- In some cereals such as rice and wheat, pollen grains lose viability within 30 minutes of their release, while in some members of Rosaceae, Leguminoseae, and Solanaceae, they maintain viability for months.

- Pollen grains can be stored for years in liquid nitrogen and used in crop breeding programmes.

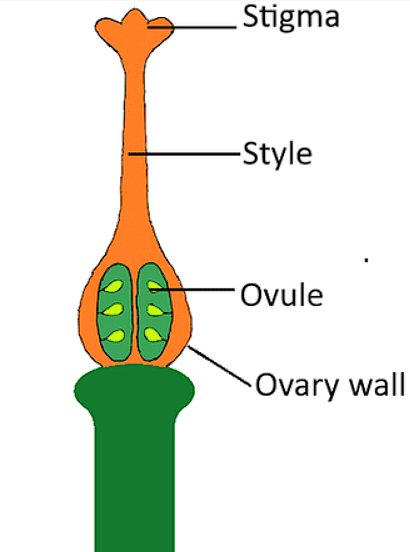

The Pistil, Megasporangium (ovule) and Embryo sac

Gynoecium is the female reproductive organ and the last whorl of the flower. It is composed of pistil and occupies the central position of the thalamus. The stigma, style, and ovary are the components of the pistil. The ovary produces ovules internally. Through meiosis, ovules produce megaspores which in turn develops into female gametophytes. As a result, egg cells are produced.

Structure of carpel

Structure of carpel

- Style - is a long slender stalk that holds the stigma. Once the pollen reaches the stigma, the style starts to become hollow and forms a tube called the pollen tube which takes the pollen to the ovaries to enable fertilization.

- Stigma– This is found at the tip of the style. It forms the head of the pistil. The stigma contains a sticky substance whose job is to catch pollen grains from different pollinators or those dispersed through the wind. They are responsible to begin the process of fertilization.

- Ovary – They form the base of the pistil. The ovary holds the ovules.

- Ovules– These are the egg cells of a flower. They are contained in the ovary. In the event of a favorable pollination where a compatible pollen reaches the stigma and eventually reaches the ovary to fuse with the ovules, this fertilized product forms the fruit and the ovules become the seeds of the fruit.

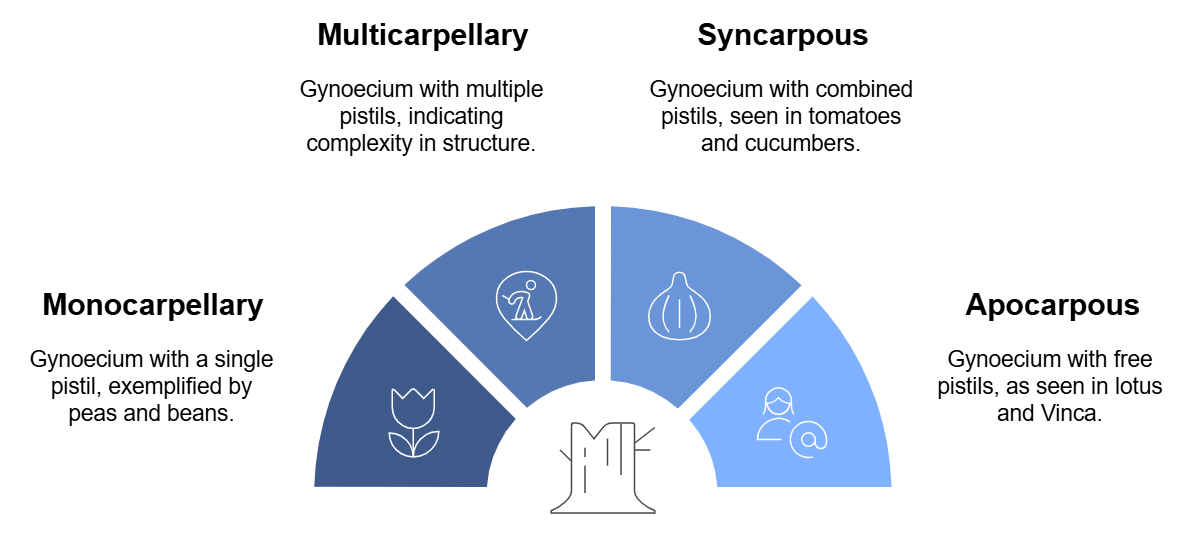

Gynoecium can be:

Types of Gynoecium

Types of Gynoecium

Megasporangium( Ovule)

An ovule or megasporangia is a small structure attached to the placenta by means of a stalk called funicle. The body of the ovule fuses with funicle in the region called hilum. Each ovule has one or two protective envelopes called integuments.

- Integuments encircle the nucellus except at the tip where a small opening called the micropyle is organised. Opposite the micropylar end, is the chalaza, representing the basal part of the ovule. Enclosed within the integuments is a mass of cells called the nucellus. Cells of the nucellus have abundant reserve food materials.

- Located in the nucellus is the embryo sac or female gametophyte. An ovule generally has a single embryo sac formed from a megaspore.

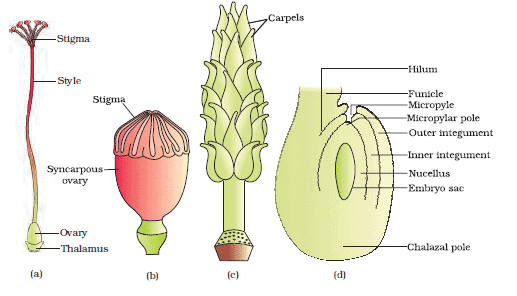

(a) A dissected flower of Hibiscus showing pistil (other floral parts have been removed);(b) Multicarpellary, syncarpous pistil of Papaver ; (c) A multicarpellary, apocarpousgynoecium of Michelia; (d) A diagrammatic view of a typical anatropous ovule

(a) A dissected flower of Hibiscus showing pistil (other floral parts have been removed);(b) Multicarpellary, syncarpous pistil of Papaver ; (c) A multicarpellary, apocarpousgynoecium of Michelia; (d) A diagrammatic view of a typical anatropous ovule

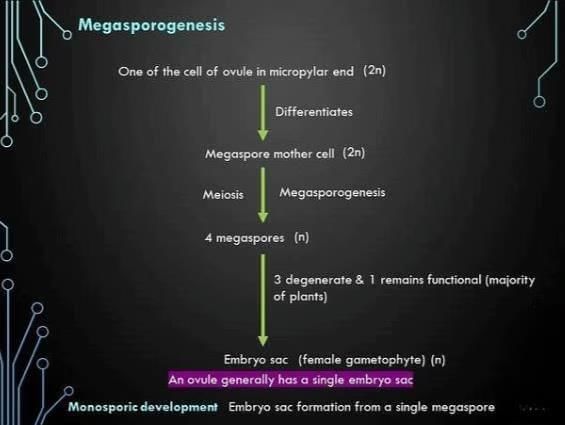

Megasporogenesis

Megasporogenesis is the process of forming megaspores from the megaspore mother cell. Here are some key points about this process:

- Megaspores are formed in ovules from a single megaspore mother cell (MMC) in the micropylar region of the nucellus.

- The MMC is a large cell that contains dense cytoplasm and a prominent nucleus.

- The MMC undergoes meiotic division, which is important for the production of four megaspores.

Female gametophyte

(i) Megaspore Development:

- In most flowering plants, one of the four megaspores formed is functional, while the other three degenerate.

- The functional megaspore develops into the female gametophyte (embryo sac).

(ii) Monosporic Development: This process, where the embryo sac forms from a single megaspore, is called monosporic development.

(iii) Ploidy Levels:

- Nucellus Cells: Diploid (2n)

- Megaspore Mother Cell (MMC): Diploid (2n)

- Functional Megaspore: Haploid (n)

- Female Gametophyte (Embryo Sac): Haploid (n)

(iv) Embryo Sac Formation:

- Initial Division: The nucleus of the functional megaspore divides mitotically to form two nuclei, which migrate to opposite poles, creating a 2-nucleate embryo sac.

- Subsequent Divisions: Two more mitotic divisions occur, leading to the 4-nucleate and then the 8-nucleate stages.

- Free Nuclear Divisions: These mitotic divisions are free nuclear, meaning they are not followed immediately by cell wall formation.

(v) Mature Embryo Sac Structure: Cell Formation: After the 8-nucleate stage, cell walls are formed, organizing the embryo sac.

(vi) Cell Distribution:

- Egg Apparatus: Three cells at the micropylar end, consisting of two synergids and one egg cell. Synergids have filiform apparatus at the micropylar tip.

- Antipodals: Three cells at the chalazal end.

- Central Cell: Contains two polar nuclei.

(vii) Final Configuration: The mature embryo sac is 7-celled but 8-nucleate.

(a) Parts of the ovule showing a large megaspore mother cell, a dyad and a tetrad of megaspores; (b) 2, 4, and 8-nucleate stages of embryo sac and a mature embryo sac; (c) A diagrammatic representation of the mature embryo sac.

(a) Parts of the ovule showing a large megaspore mother cell, a dyad and a tetrad of megaspores; (b) 2, 4, and 8-nucleate stages of embryo sac and a mature embryo sac; (c) A diagrammatic representation of the mature embryo sac.

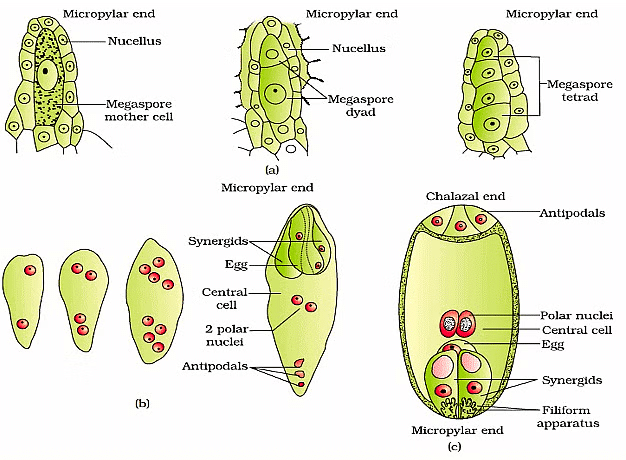

Pollination

Pollination is an ecological process carried out by all flowering plants. In this process, the matured pollen grains are transferred from the anther to the stigma for the purpose of sexual reproduction in flowering plants.

Cross-Pollination

Cross-Pollination

Kinds of pollination

(i)Autogamy:

- Pollination occurs within the same flower.

- Pollen grains transfer from the anther to the stigma of the same flower.

- Complete autogamy is rare in flowers that open and expose their anthers and stigma.

- Requires synchronization of pollen release and stigma receptivity, and proximity of anthers and stigma.

- Examples include Viola (common pansy), Oxalis, and Commelina:

- Chasmogamous Flowers: Open flowers with exposed anthers and stigma.

- Cleistogamous Flowers: Closed flowers with anthers and stigma close together, allowing self-pollination.

- Advantage of Cleistogamy: Provides assured seed-set without the need for pollinators.

- Disadvantage of Cleistogamy: Limits genetic diversity since there is no chance for cross-pollination.

(ii) Geitonogamy:

- Transfer of pollen grains from the anther to the stigma of another flower on the same plant.

- Functionally similar to cross-pollination because it involves a pollinating agent.

- Genetically similar to autogamy since the pollen comes from the same plant.

(iii) Xenogamy:

- Transfer of pollen grains from the anther to the stigma of a different plant.

- Involves genetically different pollen grains, promoting genetic diversity.

Agents of Pollination

Plants use different agents for pollination, which can be biotic or abiotic. Biotic agents are more commonly used for pollination. However, only a small proportion of plants use abiotic agents. Abiotic pollination can occur by wind and water.

Agents of pollination

Agents of pollination

1: Abiotic or Non-living

(i) Wind Pollination:

Characteristics:

- Common among abiotic pollinations.

- Pollen grains are light and non-sticky.

- Flowers have well-exposed stamens and large, feathery stigmas to catch airborne pollen.

- Often have a single ovule per ovary and many flowers clustered in an inflorescence.

- Example: Corn cob (tassels are stigmas and styles that capture pollen).

- Common in: Grasses.

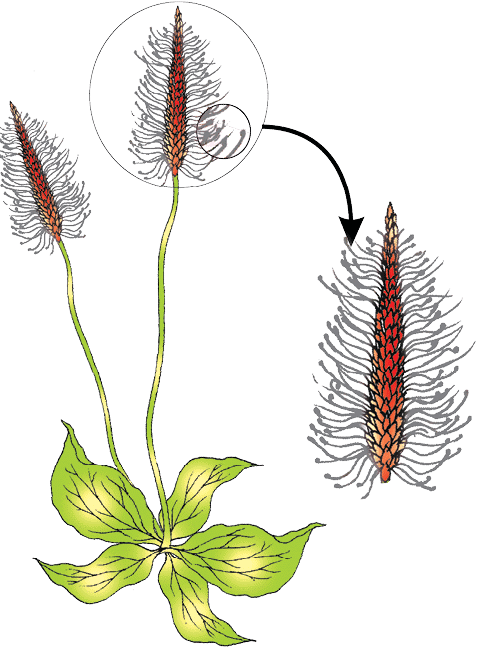

A wind-pollinated plant showing compact inflorecence and well-exposed stamens

A wind-pollinated plant showing compact inflorecence and well-exposed stamens

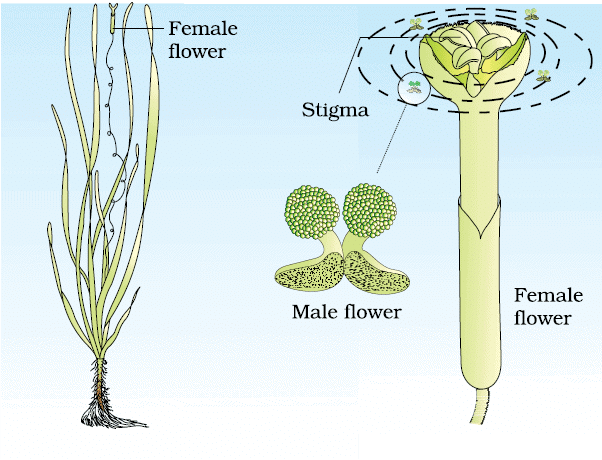

(ii) Water Pollination:

Characteristics:

- Rare and limited to about 30 genera, mostly monocotyledons.

- Water is a regular transport medium for male gametes in lower plant groups (e.g., algae, bryophytes).

- Examples of Water-Pollinated Plants:

- Freshwater: Vallisneria and Hydrilla.

- Marine: Seagrasses like Zostera.

Pollination Process:

- Vallisneria: Female flowers rise to the water surface; male pollen is released into water and carried to female flowers.

- Seagrasses (like Zostera): Female flowers stay submerged; pollen grains are released into water and carried passively.

Pollination by water in Vallisneria

Pollination by water in Vallisneria

2: Biotic or Living Agents:

Biotic agents involve living organisms that contribute to the pollination process. Flowers adapted for biotic pollination are often colorful, attractive, and emit sweet scents to lure insects, birds, and other living creatures.

(a) Pollination by insects, is common in angiosperms. Bees, butterflies, beetles, and flies are common pollinators. These flowers typically have limited pollen and rough-textured grains that easily adhere to insect limbs.

Insect Pollination

Insect Pollination

(b) Pollination by birds, involves birds like hummingbirds and honey thrushes that feed on flower nectar. These flowers have fewer pollen grains that attach to the birds' beaks and mouths, transferring to other flowers.

(c) Pollination by bats, is observed in specific trees like Kigelia Africana, Anthocephalus cadamba, and Bauhinia Monandra.

(i) Flower Adaptations for Animal Pollination:

- Insect-Pollinated Flowers:

- Typically large, colorful, fragrant, and rich in nectar.

- Small flowers are often clustered in inflorescences to increase visibility.

- Flowers attract animals through color and fragrance.

(ii) Flies and Beetles:

Attract these animals with foul odors.

(iii) Floral Rewards:

Provide nectar and pollen as rewards.

Some flowers offer safe places for laying eggs (e.g., Amorphophallus) or engage in mutualistic relationships (e.g., Yucca and moth).

(iv) Pollination Process:

Animals collect nectar and pollen, which are sticky in animal-pollinated flowers.

As animals move from flower to flower, they transfer pollen from anthers to stigmas, facilitating pollination.

(v) Pollen/Nectar Robbers:

Some insects may consume nectar or pollen without pollinating the flower. These are known as pollen or nectar robbers.

Comparison of Abiotic and Biotic Pollinated Flowers

- Both wind and water-pollinated flowers are not very colorful and do not produce nectar. This is because they rely on abiotic agents for pollination and do not need to attract animals.

- In contrast, animal-pollinated flowers are more colourful, fragrant, and rich in nectar. They need to attract animals for pollination and provide them with rewards.

Outbreeding Devices

Most flowering plants produce hermaphrodite flowers, increasing the likelihood of self-pollination. However, continued self-pollination leads to inbreeding depression.

To discourage self-pollination and encourage cross-pollination, plants have developed several mechanisms:

1. Asynchronous Pollen Release and Stigma Receptivity:

- In some species, pollen is released before the stigma becomes receptive or stigma becomes receptive before pollen is released.

- This prevents self-pollination (autogamy).

2. Different Placement of Anther and Stigma:

- In some species, the anther and stigma are positioned differently, preventing pollen from reaching the stigma of the same flower.

- This also discourages autogamy.

3. Self-Incompatibility (Genetic Mechanism):

- Prevents self-pollen (from the same flower or plant) from fertilizing the ovules.

- This happens by inhibiting pollen germination or pollen tube growth in the pistil.

4. Unisexual Flowers:

- Monoecious plants (e.g., castor and maize) have separate male and female flowers on the same plant, preventing autogamy but not geitonogamy (pollination between flowers of the same plant).

- Dioecious plants (e.g., papaya) have separate male and female plants, preventing both autogamy and geitonogamy.

Pollen-Pistil Interaction

The process from pollen deposition on the stigma to pollen tubes entering the ovule is known as pollen-pistil interaction.

Pollination does not always ensure the transfer of the right type of pollen. Sometimes, pollen from other species or self-incompatible pollen lands on the stigma. The pistil recognises the pollen and determines whether it is compatible or incompatible.

- If the pollen is compatible, the pistil accepts it and promotes post-pollination events leading to fertilisation.

- If the pollen is incompatible, the pistil rejects it by preventing pollen germination or blocking pollen tube growth in the style.

- This recognition and response involve a continuous dialogue between the pollen and pistil, mediated by their chemical components.

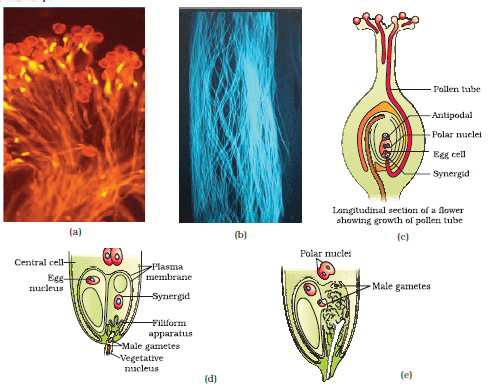

(a) Pollen grains germinating on the stigma; (b) Pollen tubes growing through the style; (c) L.S. of pistil showing path of pollen tube growth; (d) enlarged view of an egg apparatus showing entry of pollen tube into a synergid; (e) Discharge of male gametes into a synergid and the movements of the sperms, one into the egg and the other into the central cell

(a) Pollen grains germinating on the stigma; (b) Pollen tubes growing through the style; (c) L.S. of pistil showing path of pollen tube growth; (d) enlarged view of an egg apparatus showing entry of pollen tube into a synergid; (e) Discharge of male gametes into a synergid and the movements of the sperms, one into the egg and the other into the central cell

Pollen Germination and Pollen Tube Growth

After compatible pollination, the pollen grain germinates on the stigma, forming a pollen tube through one of its germ pores.

- The pollen tube grows through the stigma and style, carrying the pollen contents to the ovary.

- In some plants, pollen grains are shed in a two-celled condition (a vegetative cell and a generative cell). The generative cell divides to form two male gametes during pollen tube growth.

- In plants with three-celled pollen, the pollen tube carries two male gametes from the beginning.

- The pollen tube enters the ovule through the micropyle and then one of the synergids through the filiform apparatus, which guides pollen tube entry.

Significance of Pollen-Pistil Interaction

- Ensures successful fertilisation by allowing only compatible pollen to proceed.

- Helps in plant breeding by enabling scientists to manipulate pollen-pistil interactions for hybrid production.

- The process of pollen germination can be studied using flowers like pea, chickpea, Crotalaria, balsam, and Vinca by observing pollen grains in a sugar solution under a microscope.

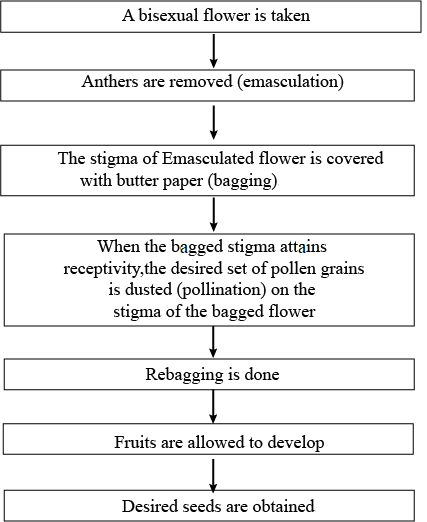

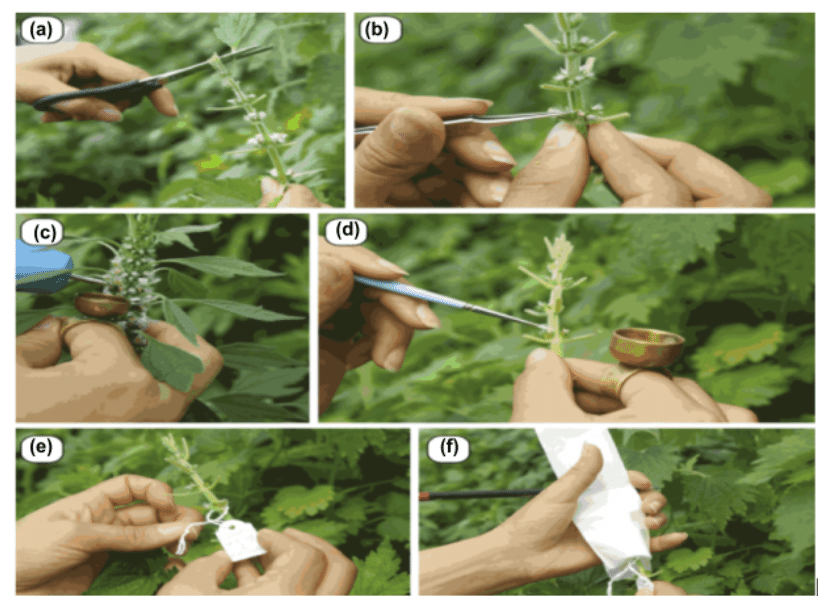

Artificial Hybridization for Crop Improvement

Artificial hybridization is a major approach in crop improvement programs to produce commercially superior varieties by combining desirable characteristics of different species and genera.

- To ensure only desired pollen grains are used for pollination and the stigma is protected from contamination, emasculation and bagging techniques are used.

- In flowers with bisexual flowers, emasculation is necessary by removing anthers from the flower bud before the anther dehisces

- The emasculated flowers have to be covered with a suitable bag to prevent contamination of the stigma with unwanted pollen, which is called bagging.

- When the stigma of bagged flower attains receptivity, mature pollen grains collected from anthers of the male parent are dusted on the stigma, and the flowers are rebagged, and the fruits allowed to develop.

- In female parents with unisexual flowers, emasculation is not required. The female flower buds are bagged before the flowers open, and pollination is carried out using the desired pollen when the stigma becomes receptive.

Fertilization

Following pollination, the pollen grains travel to the ovary via the pollen tube. Upon reaching the ovary, one male gamete fertilizes the ovule, forming a zygote, which develops into an embryo. Meanwhile, the other male gamete fuses with the polar nuclei, leading to the formation of the endosperm nucleus. This endosperm provides nourishment to the developing embryo.

Fertilization transforms the ovules into seeds, while the ovary develops into the fruit.

Fertilization in Plants

Fertilization in Plants

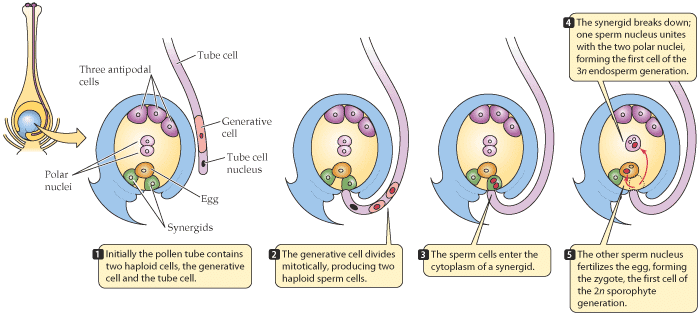

Double Fertilisation

When pollen grains land on the stigma of a flower, they produce a pollen tube that travels down to the ovary, where the embryo sacs containing the female gametes are located. The process of double fertilisation takes place when the male gametes released by the pollen tube enter the embryo sac.The Process of Double Fertilisation

During double fertilisation, two types of fusion take place:

- The male gamete fuses with the egg cell to form a diploid zygote

- The other male gamete fuses with the two polar nuclei to produce a triploid primary endosperm nucleus (PEN)

This phenomenon is called double fertilisation because two types of fertilisation take place in one embryo sac.

Formation of Endosperm and Embryo

- After triple fusion, the central cell becomes the primary endosperm cell (PEC), which develops into the endosperm. Meanwhile, the zygote develops into an embryo.

- Double fertilisation is a unique event to flowering plants and ensures the proper development of the endosperm, which provides nutrients to the developing embryo.

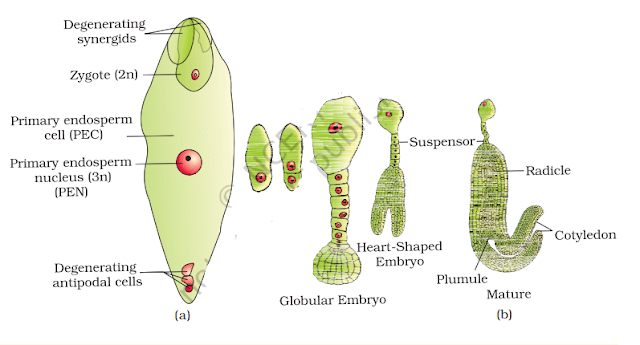

(a) Fertilised embryo sac showing zygote and Primary Endosperm Nucleus (PEN); (b) Stages in embryo development in a dicot [shown in reduced size as compared to (a)]

(a) Fertilised embryo sac showing zygote and Primary Endosperm Nucleus (PEN); (b) Stages in embryo development in a dicot [shown in reduced size as compared to (a)]

Post Fertilisation: Structure and Events

After double fertilisation, the following events occur:

- Endosperm and Embryo Development

- Maturation of Ovule(s) into Seed(s)

- Ovary Development into Fruit

1. Endosperm

Timing of Development:

- Endosperm development occurs before embryo development.

- The primary endosperm nucleus (PEN) divides repeatedly, forming a triploid endosperm tissue.

Endosperm Formation:

- Initial Stage: PEN undergoes multiple nuclear divisions, creating free nuclei. This stage is known as free-nuclear endosperm.

- Subsequent Stage: Cell walls form around these nuclei, resulting in cellular endosperm.

Examples: Coconut: Tender coconut water consists of free-nuclear endosperm (many nuclei), while the white kernel is cellular endosperm.

Endosperm Fate:

- Consumed Before Seed Maturation: In some seeds (e.g., pea, groundnut, beans), the endosperm is completely consumed by the developing embryo before seed maturation.

- Persistent Endosperm: In other seeds (e.g., castor, coconut), endosperm persists in the mature seed and is used during seed germination.

2. Embryo

The embryo develops at the micropylar end of the embryo sac, where the zygote is located. In most cases, the zygote divides only after some endosperm formation, ensuring nutrition for the developing embryo. Despite differences in seed structure, the early stages of embryo development (embryogeny) are similar in both monocotyledons and dicotyledons.

Stages of Embryogeny

The zygote undergoes sequential developmental stages:

1. Proembryo formation

2. Globular stage

3. Heart-shaped stage

4. Mature embryo formation

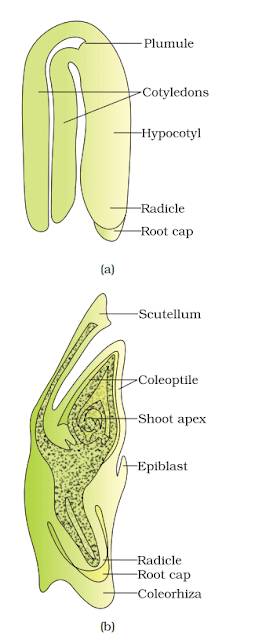

5. Structure of a Dicot Embryo

Structure of a Dicot Embryo

A typical dicot embryo consists of:

- Embryonal axis with two cotyledons.

- Epicotyl (portion above the cotyledons) ending in the plumule (stem tip).

- Hypocotyl (portion below the cotyledons) terminating in the radicle (root tip).

- Root tip, which is covered by a root cap for protection.

Structure of a Monocot Embryo

A monocot embryo has only one cotyledon. In grasses, this cotyledon is called the scutellum, located laterally on the embryonal axis.

- The lower end of the embryonal axis has the radicle and root cap, enclosed within a sheath called coleorhiza.

- The epicotyl (portion above the cotyledon attachment) contains the shoot apex and leaf primordia, enclosed in a hollow foliar structure called coleoptile.

(a) A typical dicot embryo; (b) L.S. of an embryo of grass

(a) A typical dicot embryo; (b) L.S. of an embryo of grass

3. Seed

Seeds are the end result of sexual reproduction in flowering plants. They develop from fertilized ovules inside fruits. A typical seed consists of a protective outer coat, one or more cotyledons (which store food), and an embryo axis.

Seeds in Angiosperms

- Seeds are the final product of sexual reproduction and are described as fertilised ovules.

- They develop inside fruits and consist of seed coat(s), cotyledon(s), and an embryo axis.

- Cotyledons are thick and swollen due to stored food reserves, as seen in legumes.

Types of Seeds

- Non-albuminous seeds: No residual endosperm, as it is fully consumed during embryo development (e.g., pea, groundnut).

- Albuminous seeds: Retain part of the endosperm (e.g., wheat, maize, barley, castor).

- Perisperm: In some seeds like black pepper and beet, remnants of the nucellus persist.

Seed Coat and Germination

- Integuments harden into a protective seed coat.

- The micropyle remains as a small pore for the entry of oxygen and water during germination.

- Water content reduces to 10-15% as the seed matures, slowing metabolic activity.

- The embryo may enter dormancy or germinate under favourable conditions (moisture, oxygen, temperature).

4. Fruit Formation

- As ovules mature into seeds, the ovary develops into a fruit.

- The ovary wall forms the pericarp (fruit wall).

- Fruits can be:

- Fleshy (e.g., guava, orange, mango).

- Dry (e.g., groundnut, mustard).

- Some fruits develop mechanisms for seed dispersal.

Types of Fruits

- True fruits: Develop only from the ovary.

- False fruits: Develop with the help of other floral parts (e.g., apple, strawberry, cashew).

- Parthenocarpic fruits: Develop without fertilisation, producing seedless fruits(e.g., banana).

- Parthenocarpy can be induced using growth hormones.

Advantages of Seeds in Angiosperms

- Fertilisation is independent of water, making seed formation more reliable.

- Seeds have adaptive strategies for dispersal, helping species spread.

- Stored food reserves nourish young seedlings until they can photosynthesize.

- The hard seed coat protects the embryo.

- Being a product of sexual reproduction, seeds generate genetic variations.

Role of Seeds in Agriculture

- Dehydration and dormancy allow seeds to be stored for food and future crop production.

- If seeds germinated immediately after formation, agriculture would not be possible.

- Seed longevity varies:

- Some seeds lose viability in months, while others remain viable for years.

- Some can stay alive for hundreds of years.

Longevity of Seeds

- The oldest recorded viable seed is of Lupinus arcticus, which germinated after 10,000 years of dormancy.

- A 2,000-year-old seed of Phoenix dactylifera (date palm) was discovered in King Herod’s palace near the Dead Sea and successfully germinated.

Reproductive Capacity of Flowering Plants

- Each embryo sac contains one egg.

- Multiple ovules may be present in an ovary.

- The number of ovaries per flower and flowers per tree amplify reproductive potential.

- Some fruits, like orchids, contain thousands of tiny seeds.

- Parasitic plants like Orobanche and Striga also produce numerous small seeds.

- The tiny seed of Ficus grows into a massive tree, producing billions of seeds over time.

Apomixis

- Apomixis is a type of asexual reproduction in plants that involves the formation of a seed without the fertilization of the egg cell by a sperm cell.

- The resulting offspring are genetically identical to the parent plant.

- In apomixis, the embryo sac develops into an embryo without being fertilized, and the resulting seed carries the same genetic information as the parent plant.

- This process can occur naturally in some plant species or can be induced artificially in others.

Polyembryony

- Apomixis can develop in various ways, depending on the plant species.

- In some species, a diploid egg cell forms without reduction division and develops into an embryo without fertilisation.

- In other species, such as Citrus and Mango varieties, nucellar cells surrounding the embryo sac start dividing, protrude into the embryo sac, and develop into multiple embryos within a single ovule.

- The occurrence of more than one embryo in a seed is called polyembryony.

Apomixis and Hybrid Varieties

- Apomixis produces genetically identical embryos and can be considered a type of cloning

- Hybrid varieties are being extensively cultivated to increase productivity

- However, hybrid seeds need to be produced every year, which is costly and makes them expensive for farmers

- If hybrid varieties are made into apomicts, there is no segregation of characters in the hybrid progeny

- This means farmers can keep using the hybrid seeds to raise new crops year after year without buying new hybrid seeds

- Active research is ongoing in many laboratories worldwide to understand the genetics of apomixis and transfer apomictic genes into hybrid varieties

|

59 videos|290 docs|168 tests

|

FAQs on Sexual Reproduction in Flowering Plants Chapter Notes - Biology Class 12 - NEET

| 1. What are the main structures involved in the pre-fertilisation stage of flowering plants? |  |

| 2. What is double fertilisation in flowering plants? |  |

| 3. What are the major events that occur post-fertilisation in flowering plants? |  |

| 4. What is apomixis and how does it differ from sexual reproduction? |  |

| 5. What is polyembryony in flowering plants? |  |