The Two Europes, East and West since 1945- 2 | UPSC Mains: World History PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Why And How Did Communism Collapse In Eastern Europe? |

|

| Civil War In Yugoslavia |

|

| Europe Since Maastricht |

|

| The European Union In Crisis |

|

Why And How Did Communism Collapse In Eastern Europe?

In the short period between August 1988 and December 1991, communism in eastern Europe was swept away. Poland was the first to reject communism, closely followed by Hungary and East Germany and the rest, until by the end of 1991 even Russia had ceased to be communist, after 74 years. Why did this dramatic collapse take place?

Economic failure

- Communism as it existed in eastern Europe was a failure economically. It simply did not produce the standard of living which should have been possible, given the vast resources available. The economic systems were inefficient, over-centralized and subject to too many restrictions; all the states, for example, were expected to do most of their trading within the Communist bloc. By the mid-1980s there were problems everywhere. According to Misha Glenny, a BBC correspondent in eastern Europe, the Communist Party leaderships refused to admit that the working class lived in more squalid conditions, breathing in more damaged air and drinking more toxic water, than western working classes … the communist record on health, education, housing, and a range of other social services has been atrocious.

Increasing contact with the west in the 1980s showed people how backward the east was in comparison with the west, and suggested that their living standards were falling even further. It showed also that it must be their own leaders and the communist system that were the cause of all their problems.

Mikhail Gorbachev

- Mikhail Gorbachev, who became leader of the USSR in March 1985, started the process which led to the collapse of the Soviet Empire. He recognized the failings of the system and he admitted that it was ‘an absurd situation’ that the USSR, the world’s biggest producer of steel, fuel and energy, should be suffering shortages because of waste and inefficiency (see Section 18.3 for the situation in the USSR). He hoped to save communism by revitalizing and modernizing it. He introduced new policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (economic and social reform). Criticism of the system was encouraged in the drive for improvement, provided nobody criticized the Communist Party. He also helped to engineer the overthrow of the old-fashioned, hardline communist leaders in Czechoslovakia, and he was probably involved in plotting the overthrow of the East German, Romanian and Bulgarian leaders. His hope was that more progressive leaders would increase the chances of saving communism in Russia’s satellite states.

- Unfortunately for Gorbachev, once the process of reform began, it proved impossible to control it. The most dangerous time for any repressive regime is when it begins to try and reform itself by making concessions. These are never enough to satisfy the critics, and in Russia, criticism inevitably turned against the Communist Party itself and demanded more. Public opinion even turned against Gorbachev because many people felt he was not moving fast enough.

- The same happened in the satellite states: the communist leaderships found it difficult to adapt to the new situation of having a leader in Moscow who was more progressive than they were. The critics became more daring as they realized that Gorbachev would not send Soviet troops in to fire on them. With no help to be expected from Moscow, when it came to the crisis, none of the communist governments was prepared to use sufficient force against the demonstrators (except in Romania). When they came, the rebellions were too widespread, and it would have needed a huge commitment of tanks and troops to hold down the whole of eastern Europe simultaneously. Having only just succeeded in withdrawing from Afghanistan, Gorbachev had no desire for an even greater involvement. In the end it was a triumph of ‘people power’: demonstrators deliberately defied the threat of violence in such huge numbers that troops would have had to shoot a large proportion of the population in the big cities to keep control.

Poland leads the way

General Jaruzelski, who became leader in 1981, was prepared to take a tough line: when Solidarity (the new trade union movement) demanded a referendum to demonstrate the strength of its support, Jaruzelski declared martial law (that is, the army took over control), banned Solidarity and arrested thousands of activists. The army obeyed his orders because everybody was still afraid of Russian military intervention. By July 1983 the government was in firm control: Jaruzelski felt it safe to lift martial law and Solidarity members were gradually released. But the underlying problem was still there: all attempts to improve the economy failed. In 1988 when Jaruzelski tried to economize by cutting government subsidies, protest strikes broke out because the changes sent food prices up. This time Jaruzelski decided not to risk using force; he knew that there would be no backing from Moscow, and realized that he needed opposition support to deal with the economic crisis. Talks opened in February 1989 between the communist government, Solidarity and other opposition groups (the Roman Catholic Church had been loud in its criticisms). By April 1989, sensational changes in the constitution had been agreed:

- Solidarity was allowed to become a political party;

- there were to be two houses of parliament, a lower house and a senate;

- in the lower house, 65 per cent of the seats had to be communist;

- the senate was to be freely elected – no guaranteed communist seats;

- the two houses voting together would elect a president, who would then choose a prime minister.

In the elections of June 1989, Solidarity won 92 out of the 100 seats in the senate and 160 out of the 161 seats which they could fight in the lower house. A compromise deal was worked out when it came to forming a government: Jaruzelski was narrowly elected president, thanks to all the guaranteed communist seats in the lower house, but he chose a Solidarity supporter, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, as prime minister – the first non-communist leader in the eastern bloc (August). Mazowiecki chose a mixed government of communists and Solidarity supporters.

The new constitution proved to be only transitional. After the collapse of communism in the other east European states, further changes in Poland removed the guaranteed communist seats, and in the elections of December 1990, Lech Wałęsa, the Solidarity leader, was elected president. The peaceful revolution in Poland was complete.

The peaceful revolution spreads to Hungary

- Once the Poles had thrown off communism without interference from the USSR, it was only a matter of time before the rest of eastern Europe tried to follow suit. In Hungary even Kádár himself admitted in 1985 that living standards had fallen over the previous five years, and he blamed poor management, poor organization and outdated machinery and equipment in the state sector of industry. He announced new measures of decentralization – company councils and elected works managers. By 1987 there was conflict in the Communist Party between those who wanted more reform and those who wanted a return to strict central control. This reached a climax in May 1988 when, amid dramatic scenes at the party conference, Kádár and eight of his supporters were voted off the Politburo, leaving the progressives in control.

- But as in the USSR, progress was not drastic enough for many people. Two large opposition parties became increasingly active. These were the liberal Alliance of Free Democrats, and the Democratic Forum, which stood for the interests of farmers and peasants. The Hungarian communist leadership, following the example of the Poles, decided to go peacefully. Free elections were held in March 1990, and in spite of a change of name to the Hungarian Socialist Party, the communists suffered a crushing defeat. The election was won by the Democratic Forum, whose leader, József Antall, became prime minister.

Germany reunited

In East Germany, Erich Honecker, who had been communist leader since 1971, refused all reform and intended to stand firm, along with Czechoslovakia, Romania and the rest, to keep communism in place. However, Honecker was soon overtaken by events:

- Gorbachev, desperate to get financial help for the USSR from West Germany, paid a visit to Chancellor Kohl in Bonn, and promised to help bring an end to the divided Europe, in return for German economic aid. In effect he was secretly promising freedom for East Germany (June 1989).

- During August and September 1989, thousands of East Germans began to escape to the west via Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, when Hungary opened its frontier with Austria.

- The Protestant Church in East Germany became the focus of an opposition party called New Forum, which campaigned to bring an end to the repressive and atheistic communist regime. In October 1989 there was a wave of demonstrations all over East Germany demanding freedom and an end to communism.

Honecker wanted to order the army to open fire on the demonstrators, but other leading communists were not prepared to cause widespread bloodshed. They dropped Honecker, and his successor Egon Krenz made concessions. The Berlin Wall was breached (9 November 1989) and free elections were promised.

When the great powers began to drop hints that they would not stand in the way of a reunited Germany, the West German political parties moved into the East. Chancellor Kohl staged an election tour, and the East German version of his party (CDU) won an overwhelming victory (March 1990). The East German CDU leader, Lothar de Maizière, became prime minister. He was hoping for gradual moves towards reunification, but again the pressure of ‘people power’ carried all before it. Nearly everybody in East Germany seemed to want immediate union.

The USSR and the USA agreed that reunification could take place; Gorbachev promised that all Russian troops would be withdrawn from East Germany by 1994. France and Britain, who were less happy about German reunification, felt bound to go along with the flow. Germany was formally reunited at midnight on 3 October 1990. In elections for the whole of Germany (December 1990) the conservative CDU/CSU alliance, together with their liberal FDP supporters, won a comfortable majority over the socialist SDP. The communists (renamed the Party of Democratic Socialism – PDS) won only 17 of the 662 seats in the Bundestag (lower house of parliament). Helmut Kohl became the first Chancellor of all Germany since the Second World War.

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia had one of the most successful economies of eastern Europe. She traded extensively with the west and her industry and commerce remained buoyant throughout the 1970s. But during the early 1980s the economy ran into trouble, mainly because there had been very little attempt to modernize industry. Husák, who had been in power since 1968, resigned (1987), but his successor, Miloš Jakeš, did not have a reputation as a reformer. Then things changed suddenly in a matter of days, in what became known as the Velvet Revolution. On 17 November 1989 there was a huge demonstration in Prague, at which many people were injured by police brutality. Charter 77, now led by the famous playwright Václav Havel, organized further opposition, and after Alexander Dubček had spoken at a public rally for the first time since 1968, a national strike was declared. This was enough to topple the communist regime: Jakes resigned and Havel was elected president (29 December 1989).

The rest of eastern Europe

The end of communism in the remaining states of eastern Europe was less clear-cut.

- Romania

In Romania the communist regime of Nicolae Ceauşescu (leader since 1965) was one of the most brutal and repressive anywhere in the world. His secret police, the Securitate, were responsible for many deaths. When the revolution came, it was short and bloody: it began in Timisoara, a town in western Romania, with a demonstration in support of a popular priest who was being harassed by the Securitate. This was brutally put down and many people were killed (17 December 1989). This caused outrage throughout the country, and when, four days later, Ceauşescu and his wife appeared on the balcony of Communist Party headquarters in Bucharest to address a massed rally, they were greeted with boos and shouts of ‘murderers of Timisoara’. Television coverage was abruptly halted and Ceauşescu abandoned his speech. It seemed as though the entire population of Bucharest now streamed out onto the streets. At first the army fired on the crowds and many were killed and wounded. The following day the crowds came out again; but by now the army was refusing to continue the killing, and the Ceauşescu had lost control. They were arrested, tried by a military tribunal and shot (25 December 1989).

The hated Ceauşescu had gone, but many elements of communism remained in Romania. The country had never had democratic government, and opposition had been so ruthlessly crushed that there was no equivalent of the Polish Solidarity and Czech Charter 77. When a committee calling itself the National Salvation Front (NSF) was formed, it was full of former communists, though admittedly they were communists who wanted reform. Ion Iliescu, who had been a member of Ceauşescu’s government until 1984, was chosen as president. He won the presidential election of May 1990, and the NSF won the elections for a new parliament. They strongly denied that the new government was really a communist one under a different name. - Bulgaria

In Bulgaria the communist leader Todor Zhivkov had been in power since 1954. He had stubbornly refused all reforms, even when pressurized by Gorbachev. The progressive communists decided to get rid of him. The Politburo voted to remove him (December 1989) and in June 1990 free elections were held. The communists, now calling themselves the Bulgarian Socialist Party, won a comfortable victory over the main opposition party, the Union of Democratic Forces, probably because their propaganda machine told people that the introduction of capitalism would bring economic disaster. - Albania

Albania had been communist since 1945 when the communist resistance movement seized power and set up a republic; so, as with Yugoslavia, the Russians were not responsible for the introduction of communism. Since 1946 until his death in 1985 the leader had been Enver Hoxha, who was a great admirer of Stalin and copied his system faithfully. Under its new leader, Ramiz Alia, Albania was still the poorest and most backward country in Europe. During the winter of 1991 many young Albanians tried to escape from their poverty by crossing the Adriatic Sea to Italy, but most of them were sent back. By this time student demonstrations were breaking out, and statues of Hoxha and Lenin were overturned. Eventually the communist leadership bowed to the inevitable and allowed free elections. In 1992 the first non-communist president, Sali Berisha, was elected. - Yugoslavia

The most tragic events took place in Yugoslavia, where the end of communism led to civil war and the break-up of the country.

Eastern Europe after communism

The states of eastern Europe faced broadly similar problems: how to change from a planned or ‘command’ economy to a free economy where ‘market forces’ ruled. Heavy industry, which in theory should have been privatized, was mostly old-fashioned and uncompetitive; it had now lost its guaranteed markets within the communist bloc, and so nobody wanted to buy shares in it. Although shops were better stocked than before, prices of consumer goods soared and very few people could afford to buy them. The standard of living was even lower than under the final years of communism, and very little help was forthcoming from the west. Many people had expected a miraculous improvement, and, not making allowances for the seriousness of the problems, they soon grew disillusioned with their new governments.

- The East Germans were the most fortunate, having the wealth of the former West Germany to help them. But there were tensions even here: many West Germans resented the vast amounts of ‘their’ money being poured into the East, and they had to pay higher taxes and suffer higher interest rates. The easterners resented the large numbers of westerners who now moved in and took the best jobs.

- In Poland the first four years of non-communist rule were hard for ordinary people as the government pushed ahead with its reorganization of the economy. By 1994 there were clear signs of recovery, but many people were bitterly disappointed with their new democratic government. In the presidential election of December 1995, Lech Wałęsa was defeated by a former Communist Party member, Aleksander Kwaśniewski.

- In Czechoslovakia there were problems of a different kind: Slovakia, the eastern half of the country, demanded independence, and for a time civil war seemed a strong possibility. Fortunately a peaceful settlement was worked out and the country split into two – the Czech Republic and Slovakia (1992).

- Predictably, the slowest economic progress was made in Romania, Bulgaria and Albania, where the first half of the 1990s was beset by falling output and inflation.

Civil War In Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia was formed after the First World War, and consisted of the pre-First World War state of Serbia, plus territory gained by Serbia from Turkey in 1913 (containing many Muslims), and territory taken from the defeated Habsburg Empire. It included people of many different nationalities, and the state was organized on federal lines. It consisted of six republics – Serbia, Croatia, Montenegro, Slovenia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Macedonia. There were also two provinces – Vojvodina and Kosovo – which were associated with Serbia. Under communism and the leadership of Tito, the nationalist feelings of the different peoples were kept strictly under control, and people were encouraged to think of themselves primarily as Yugoslavs rather than as Serbs or Croats. The different nationalities lived peacefully together, and had apparently succeeded in putting behind them memories of the atrocities committed during the Second World War. One such atrocity was when Croat and Muslim supporters of the fascist regime set up by the Italians to rule Croatia and Bosnia during the war were responsible for the murder of some 700 000 Serbs.

However, there was still a Croat nationalist movement, and some Croat nationalist leaders, such as Franjo Tudjman, were given spells in jail. Tito (who died in 1980) had left careful plans for the country to be ruled by a collective presidency after his death. This would consist of one representative from each of the six republics and one from each of the two provinces; a different president of this council would be elected each year.

Things begin to go wrong

Although the collective leadership seemed to work well at first, in the mid-1980s things began to go wrong.

- The economy was in trouble, with inflation running at 90 per cent in 1986 and unemployment standing at over a million – 13 per cent of the working population. There were differences between areas: for example, Slovenia was reasonably prosperous while parts of Serbia were poverty-stricken.

- Slobodan Milošević, who became president of Serbia in 1988, bears much of the responsibility for the tragedy that followed. He deliberately stirred up Serbian nationalist feelings to increase his own popularity, using the situation in Kosovo. He claimed that the Serbian minority in Kosovo were being terrorized by the Albanian majority, though there was no definite evidence of this. The Serbian government’s hardline treatment of the Albanians led to protest demonstrations and the first outbreaks of violence. Milošević remained in power after the first free elections in Serbia in 1990, having successfully convinced the voters that he was now a nationalist and not a communist. He wanted to preserve the united federal state of Yugoslavia, but intended that Serbia should be the dominant republic.

- By the end of 1990 free elections had also been held in the other republics, and new non-communist governments had taken over. They resented Serbia’s attitude, none more so than Franjo Tudjman, former communist and now leader of the right-wing Croatian Democratic Union and president of Croatia. He did all he could to stir up Croatian nationalism and wanted an independent state of Croatia.

- Slovenia also wanted to become independent, and so the future looked bleak for the united Yugoslavia. Only Milošević opposed the break-up of the state, but he wanted it kept on Serbian terms and refused to make any concessions to the other nationalities. He refused to accept a Croat as president of Yugoslavia (1991) and used Yugoslav federal cash to help the Serb economy.

- The situation was complicated because each republic had ethnic minorities: there were about 600 000 Serbs living in Croatia – about 15 per cent of the population – and about 1.3 million Serbs in Bosnia-Herzegovina – roughly a third of the population. Tudjman would give no guarantees to the Serbs of Croatia, and this gave Serbia the excuse to announce that she would defend all Serbs forced to live under Croatian rule. War was not inevitable: with statesmanlike leaders prepared to make sensible concessions, peaceful solutions could have been found. But clearly, if Yugoslavia broke up, with men like Milošević and Tudjman in power, there was little chance of a peaceful future.

The move to war: the Serb–Croat War

- Crisis-point was reached in June 1991 when Slovenia and Croatia declared themselves independent, against the wishes of Serbia. Fighting seemed likely between troops of the Yugoslav federal army (mainly Serbian) stationed in those countries, and the new Croatian and Slovenian militia armies, which had just been formed. Civil war was avoided in Slovenia mainly because there were very few Serbs living there. The EC was able to act as mediator, and secured the withdrawal of Yugoslav troops from Slovenia.

- However, it was a different story in Croatia, with its large Serbian minority. Serbian troops invaded the eastern area of Croatia (eastern Slavonia) where many Serbs lived, and other towns and cities, including Dubrovnik on the Dalmatian coast, were shelled. By the end of August 1991 they had captured about one-third of the country. Only then, having captured all the territory he wanted, did Milošević agree to a ceasefire. A UN force of 13 000 troops – UNPROFOR – was sent to police the ceasefire (February 1992). By this time the international community had recognized the independence of Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The war in Bosnia-Herzegovina

- Just as hostilities between Croatia and Serbia were dying down, an even more bloody struggle was about to break out in Bosnia, which contained a mixed population – 44 per cent Muslim, 33 per cent Serb and 17 per cent Croat. Bosnia declared itself independent under the presidency of the Muslim Alija Izetbegović (March 1992). The EC recognized its independence, making the same mistake as it had done with Croatia – it failed to make sure that the new government guaranteed fair treatment for its minorities. The Bosnian Serbs rejected the new constitution and objected to a Muslim president. Fighting soon broke out between Bosnian Serbs, who received help and encouragement from Serbia, and Bosnian Muslims. The Serbs hoped that a large strip of land in the east of Bosnia, which bordered onto Serbia, could break away from the Muslim-dominated Bosnia and become part of Serbia. At the same time Croatia attacked and occupied areas in the north of Bosnia where most of the Bosnian Croats lived.

- Atrocities were committed by all sides, but it seemed that the Bosnian Serbs were the most guilty. They carried out ‘ethnic cleansing’, which meant driving out the Muslim civilian population from Serb-majority areas, putting them into camps, and in some cases murdering all the men. Such barbarism had not been seen in Europe since the Nazi treatment of the Jews during the Second World War. Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, was besieged and shelled by the Serbs, and throughout the country there was chaos: two million refugees had been driven out of their homes by ‘ethnic cleansing’ and not enough food and medical supplies were available.

- The UN force, UNPROFOR, did its best to distribute aid, but its job was very difficult because it had no supporting artillery or aircraft. Later the UN tried to protect the Muslims by declaring Srebrenica, Zepa and Gorazde, three mainly Muslim towns in the Serb-majority region, as ‘safe areas’; but not enough troops were provided to defend them if the Serbs decided to attack. The EC was reluctant to send any troops and the Americans felt that Europe should be able to sort out its own problems. However, they did all agree to put economic sanctions on Serbia to force Milošević to stop helping the Bosnian Serbs. The war dragged on into 1995; there were endless talks, threats of NATO action and attempts to get a ceasefire, but no progress could be made.

During 1995 crucial changes took place which enabled a peace agreement to be signed in November. Serb behaviour eventually proved too much for the international community:

- Serb forces again bombarded Sarajevo, killing a number of people, after they had promised to withdraw their heavy weapons (May).

- Serbs seized UN peacekeepers as hostages to deter NATO air strikes.

- Serbs attacked and captured Srebrenica and Zepa, two of the UN ‘safe areas’, and at Srebrenica they committed perhaps the ultimate act of barbarism, killing about 8000 Muslims in a terrible final burst of ‘ethnic cleansing’ (July).

After this, things moved more quickly:

- The Croats and Muslims (who had signed a ceasefire in 1994) agreed to fight together against the Serbs. The areas of western Slavonia (May) and the Krajina (August) were recaptured from the Serbs.

- At a conference in London attended by the Americans, it was agreed to use NATO air strikes and to deploy a ‘rapid reaction force’ against the Bosnian Serbs if they continued their aggression.

- The Bosnian Serbs ignored this and continued to shell Sarajevo; 27 people were killed by a single mortar shell on 28 August. This was followed by a massive NATO bombing of Bosnian Serb positions, which continued until they agreed to move their weapons away from Sarajevo. More UN troops were sent, though in fact the UN position was weakened because NATO was now running the operation. By this time the Bosnian Serb leaders, Radovan Karadžić an d Ge neral Ml adić, had been indicted by the European Court for war crimes.

- President Milošević of Serbia had now had enough of the war and wanted to get the economic sanctions on his country lifted. With the Bosnian Serb leaders discredited in international eyes as war criminals, he was able to represent the Serbs at the conference table.

- With the Americans now taking the lead, a ceasefire was arranged, and Presidents Clinton and Yeltsin agreed to co-operate on peace arrangements. A peace conference met in the USA at Dayton (Ohio) in November and a treaty was formally signed in Paris (December 1995):

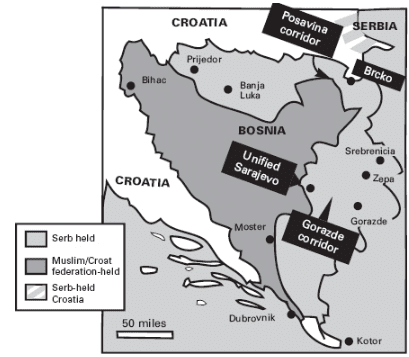

(i) Bosnia was to remain one state with a single elected parliament and president, and a unified Sarajevo as its capital.

(ii) The state would consist of two sections: the Bosnian Muslim/Croat federation and the Bosnian Serb republic.

(iii) Gorazde, the surviving ‘safe area’, was to remain in Muslim hands, linked to Sarajevo by a corridor through Serb territory.

(iv) All indicted war criminals were banned from public life.

(v) All Bosnian refugees, over two million of them, had the right to return, and there was to be freedom of movement throughout the new state.

(vi) 60 000 NATO troops were to police the settlement.

(vii) It was understood that the UN would lift the economic sanctions on Serbia.

There was general relief at the peace, though there were no real winners, and the settlement was full of problems. Only time would tell whether it was possible to maintain the new state (Map 10.3) or whether the Bosnian Serb republic would eventually try to break away and join Serbia.

Conflict in Kosovo

There was still the problem of Kosovo, where the Albanian majority bitterly resented Milošević’s hardline policies and the loss of much of their local provincial autonomy. Non-violent protests began as early as 1989, led by Ibrahim Rugova. The sensational events in Bosnia diverted attention away from the Kosovo situation, which was largely ignored during the peace negotiations in the USA in 1995. Since peaceful protest made no impression on Milošević, more radical Albanian elements came to the forefront with the formation of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). By 1998 the situation had reached the proportions of civil war, as the Serb government security forces tried to suppress the KLA. In the spring of 1999 Serb forces unleashed a full-scale offensive, committing atrocities against the Albanians. These were widely reported abroad and the world’s attention at last focused on Kosovo. Map 10.3 The Bosnian Peace Settlement

Map 10.3 The Bosnian Peace Settlement

When peace negotiations broke down, the international community decided that something must be done to protect the Albanians of Kosovo. NATO forces carried out controversial bombing attacks against Serbia, hoping to force Milošević to give way. However, this only made him more determined: he ordered a campaign of ethnic cleansing which drove hundreds of thousands of ethnic Albanians out of Kosovo and into the neighbouring states of Albania, Macedonia and Montenegro. NATO air strikes continued, and by June 1999, with his country’s economy in ruins, Milošević accepted a peace agreement worked out by Russia and Finland. He was forced to withdraw all Serb troops from Kosovo; many of the Serb civilian population, afraid of Albanian reprisals, went with them. Most of the Albanian refugees were then able to return to Kosovo. A UN and NATO force of over 40 000 arrived to keep the peace, while UNMIK (UN Mission to Kosovo) was to supervise the administration of the country until its own government was capable of taking over.

At the end of 2003 there were still 20 000 peacekeeping troops there, and the Kosovars were becoming impatient, complaining of poverty, unemployment, and corruption among the members of UNMIK.

The downfall of Milošević

- By 1998, Milošević had served two terms as president of Serbia, and the constitution prevented him from standing for a third term. However, he managed to hold on to power by getting the Yugoslav federal parliament to appoint him president of Yugoslavia in 1997 (though Yugoslavia by then consisted only of Serbia and Montenegro). In May 1999 he was indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia (at the Hague in the Netherlands), on the grounds that as president of Yugoslavia, he was responsible for crimes against international law committed by federal Yugoslav troops in Kosovo.

- Public opinion gradually turned against Milošević during 2000, because of economic difficulties, food and fuel shortages and inflation. The presidential election of September 2000 was won by his chief opponent, Vlojislav Koštunica, b ut a c onstitutional c ourt declared the result null and void. Massive anti-Milošević demonstrations took place in the capital, Belgrade. When crowds stormed the federal parliament and took control of the TV stations, Milošević conceded defeat and Kostunica became president. In 2001, Milošević was arrested and handed over to the International Tribunal in The Hague to face the war crimes charges. His trial opened in July 2001 and he chose to conduct his own defence. No verdict had been reached when he died in March 2006.

- However, the new government was soon struggling to cope with Milošević’s legacy: an empty treasury, an economy ruined by years of international sanctions, rampant inflation and a fuel crisis. The standard of living fell dramatically for most people. The parties which had united to defeat Milošević soon fell out. In the elections at the end of 2003 the extreme nationalist Serbian Radicals emerged as the largest single party, well ahead of Koštunica’s party, which came second. The leader of the Radicals, Vojislavšešelj, who was said to be an admirer of Hitler, was in jail in The Hague awaiting trial on war crimes charges. The election result was a great disappointment to the USA and the EU, which were both hoping that extreme Serb nationalism had been eradicated. In July 2008 Radovan Karadžić, the former Bosnian Serb leader, was arrested after 13 years in hiding and sent to The Hague to be tried for war crimes.

Europe Since Maastricht

With the continued success of the European Union, more states applied to join. In January 1995, Sweden, Finland and Austria became members, bringing the total membership to 15. Only Norway, Iceland and Switzerland of the main western European states remained outside. Important changes were introduced by the Treaty of Amsterdam, signed in 1997. This further developed and clarified some of the points of the 1991 Maastricht agreement: the Union undertook to promote full employment, better living and working conditions, and more generous social policies. The Council of Ministers was given the power to penalize member states which violated human rights; and the European parliament was given more powers. The changes came into effect on 1 May 1999.

Enlargement and reform

As Europe moved into the new millennium, the future looked exciting. The new European currency – the euro – was introduced in 12 of the member states on 1 January 2002. And there was the prospect of a gradual enlargement of the Union. Cyprus, Malta and Turkey had made applications for membership, and so had Poland and Hungary, all of whom hoped to join in 2004. Other countries in eastern Europe were keen to join – including the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Croatia, Slovenia, Bulgaria and Romania. There seemed every chance that sooner or later the Union would double in size. This prospect raised a number of issues and concerns.

- It was suggested that most of the former communist states of eastern Europe were so economically backward that they would be unable to join on equal terms with the advanced members such as Germany and France.

- There were fears that the Union would become too large: this would slow down decision-making and make it impossible to get consensus on any major policy.

- The federalists, who wanted closer political integration, believed that this would become almost impossible in a Union of some 25 to 30 states, unless a two-speed Europe emerged. States in favour of integration could move rapidly towards a federal system similar to the one in the USA, while the rest could move more slowly, or not at all, as the case might be.

- There was a feeling that the Union’s institutions needed reforming to make them more open, more democratic and more efficient – in order to speed up policy-making. The Union’s prestige and authority took a severe blow in March 1999 when a report revealed widespread corruption and fraud in high places; the entire Commission of 20 members was forced to resign.

The Treaty of Nice

It was to address the need for reform, in preparation for enlargement, that the Treaty of Nice was agreed in December 2000 and formally signed in February 2001; it was scheduled to come into operation on 1 January 2005.

- New voting rules were to be introduced in the Council of Ministers for the approval of policies. Many areas of policy had required a unanimous vote, which meant that one country could effectively veto a proposal. Now most policy areas were transferred to a system known as ‘qualified majority voting’ (QMV); this required that a new policy needed to be approved by members representing at least 62 per cent of the EU population, and the support of either a majority of members or a majority of votes cast. However, taxation and social security still required unanimous approval. The membership of the Council was to be increased: the ‘big four’ (Germany, UK, France and Italy) were each to have 29 members instead of 10, while the smaller states had their membership increased by roughly similar proportions – Ireland, Finland and Denmark, 7 members instead of 4; and Luxembourg, 4 members instead of 2. When Poland joined in 2004, it would have 27 members, the same number as Spain.

- The composition of the European parliament was to be changed to reflect more closely the size of each member’s population. This involved all except Germany and Luxembourg having fewer MEPs than previously – Germany, by far the largest member with a population of 82 million, was to keep its 99 seats, Luxembourg, the smallest with 400 000, was to keep its 6 seats. The UK (59.2 million), France (59 million) and Italy (57.6 million) were each to have 72 seats instead of 87; Spain (39.4 million) was to have 50 seats instead of 64, and so on, down to Ireland (3.7 million), which would have 12 seats instead of 15. On the same basis, provisional figures were set for the likely new members: for example Poland, with a population similar in size to that of Spain, would also have 50 seats, and Lithuania (like Ireland with 3.7 million) would have 12 seats.

- The five largest states, Germany, UK, France, Italy and Spain, were to have only one European commissioner each instead of two. Each member state would have one commissioner, up to a maximum of 27, and the president of the Commission was to have more independence from national governments.

- ‘Enhanced co-operation’ was to be allowed. This meant that any group of eight or more member states which wanted to move to greater integration in particular areas would be able to do so.

- A German–Italian proposal was accepted that a conference should be held to clarify and formalize the constitution of the EU, by 2004.

- A plan for a European Union Rapid Reaction Force (RRF) of 60 000 troops was approved, to provide military back-up in case of emergency, though it was stressed that NATO would still be the basis of Europe’s defence system. This did not please the French president, Jacques Chirac, who wanted the RRF to be independent of NATO. Nor did it please the USA, which was afraid that the EU defence initiative would eventually exclude the USA. In October 2003, as discussions were taking place in Brussels on how best to proceed with EU defence plans, the US government complained that it was being kept in the dark about Europe’s intentions, claiming that the EU plans ‘represented one of the greatest dangers to the transatlantic relationship’. It seemed that although the Americans wanted Europe to take on more of the world’s defence and anti-terrorist burden, it intended this to be done under US direction, working through NATO, not independently.

Before the Treaty of Nice could be put into operation in January 2005, it had to be approved by all 15 member states. It was therefore a serious blow when, in June 2001, Ireland voted in a referendum to reject it. Ireland had been one of the most co-operative and pro-European members of the Union; but the Irish resented the fact that the changes would increase the power of the larger states, especially Germany, and reduce the influence of the smaller states. Nor were they happy at the prospect of Irish participation in peacekeeping forces. There was still time for the Irish to change their minds, but the situation would need careful handling if voters were to be persuaded to back the agreement. When the European Commission president, Romano Prodi of Italy, announced that enlargement of the Union could go ahead in spite of the Irish vote, the Irish government was outraged. His statement prompted accusations from across the Union that its leaders were out of touch with ordinary citizens.

Problems and tensions

Instead of a smooth transition to an enlarged and united Europe in May 2004, the period after the signing of the Treaty of Nice turned out to be full of problems and tensions. Some had been foreseen, but most of them were quite unexpected.

- Predictably, the divisions widened between those who wanted a much closer political union – a sort of United States of Europe – and those who wanted a looser association in which power remained in the hands of the member states. Chancellor Gerhard Schröder of Germany wanted a strong European government with more power given to the European Commission and the Council of Ministers, and a European Union constitution embodying his vision of a federal system. He was supported by Belgium, Finland and Luxembourg. On the other hand, Britain felt that political integration had gone far enough, and did not want the governments of the individual states to lose any more of their powers. The way forward was through closer co-operation between the national governments, not through handing control over to a federal government in Brussels or Strasbourg.

- The terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 in the USA threw the EU into confusion. The EU leaders were quick to declare solidarity with the USA and to promise all possible co-operation in the war against terrorism. However, foreign and defence issues were areas where the EU was not well equipped to take rapid collective action. It was left to the leaders of individual states – Schröder, Chirac and UK prime minister Blair – to take initiatives and promise military help against terrorism. This in itself was resented by the smaller member states, which felt they were being by-passed and ignored.

- The attack on Iraq by the USA and the UK in March 2003 (see Section 12.4) caused new tensions. Germany and France were strongly opposed to any military action not authorized by the UN; they believed that it was possible to disarm Iraq by peaceful means, and that war would cause the deaths of thousands of innocent civilians, destroy the stability of the whole region and hamper the global struggle against terrorism. On the other hand, Spain, Italy, Portugal and Denmark, together with the prospective new members – Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic – were in favour of Britain’s joint action with the USA. American Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld dismissed the German and French opposition, claiming that they represented ‘old Europe’. An emergency European Council meeting was held in Brussels in February, but it failed to resolve the basic differences: the UK, Italy and Spain wanted immediate military action while France and Germany pressed for more diplomacy and more weapons inspectors. This failure to agree on a unified response to the Iraq situation did not bode well for the prospects of formulating a common foreign and defence policy, as required by the new EU constitution due to be debated in December 2003.

- A rift of a different sort opened up over budgetary matters. In the autumn of 2003 it was revealed that both France and Germany had breached the EU rule, laid down at Maastricht, that budget deficits must not exceed 3 per cent of GDP. However, no action was taken: the EU finance ministers decided that both states could have an extra year to comply. In the case of France, it was the third consecutive year that the 3 per cent ceiling had been breached. This bending of the rules in favour of the two largest member states infuriated the smaller members. Spain, Austria, Finland and the Netherlands opposed the decision to let them off. It raised a number of questions: what would happen if smaller countries broke the rules – would they be let off too? If so, wouldn’t that make a mockery of the whole budgetary system? Was the 3 per cent limit realistic anyway in a time of economic stagnation?

- The most serious blow – in December 2003 – came when a summit meeting in Brussels collapsed without reaching agreement on the new EU constitution, which was designed to streamline and simplify the way the Union worked. Disagreement over the issue of voting powers was the main stumbling block.

Failure to agree on the new constitution was not a total disaster; the enlargement of the EU was still able to go ahead as planned on 1 May 2004; the ten new members were the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia. But it was clear that the future of the Union was going to be fraught with problems. With some 25 or more members to deal with, the main issue was how to balance the interests of the smaller and larger states. Happily, most of the problems seemed to have been overcome when, in June 2004, a Constitutional Treaty was drawn up, to be presented to member states for ratification. The new constitution was something of a triumph: it brought together the confusing hotchpotch of previous treaties, and made for much smoother decision-making. It appeared to allow the national parliaments rather more powers than previously – for example, there was a procedure for members to leave the Union if they chose to; and states kept their veto on taxation, foreign policy and defence. The areas over which the EU had overriding control were competition policy, customs, trade policy and protection of marine life. The dispute over the voting system was also resolved: for a measure to pass, it must be supported by at least 15 countries representing 65 per cent of the EU’s total population of 455 million; at least four countries with 35 per cent of the population would be required to block a measure. This was a safeguard to prevent the biggest countries from riding roughshod over the interests of the smaller ones. Spain, which had protested strongly that the previous proposals disadvantaged the smaller members, was happy with the compromise. The next problem was to get the new constitution ratified by all the members, and this would involve at least six national referendums. Unfortunately in 2005 it was rejected by Dutch and French voters, and it was decided that there should be a ‘period of reflection’.

Eventually a new agreement was drawn up, preserving many of the reforms of the previous constitution but amending the ones that had raised objections. Signed by all 27 member states at Lisbon in December 2007, the stated aim of the treaty was ‘to complete the process started by the Treaty of Amsterdam [1997] and by the Treaty of Nice [2001] with a view to enhancing the efficiency and democratic legitimacy of the Union and to improving the coherence of its actions’.

The European Union In Crisis

In a referendum held in June 2008 well over half the Irish voters rejected the Lisbon Treaty. The Germans and French, who were mainly responsible for the form of the treaty, were furious. The Germans threatened Ireland with expulsion from the EU, and President Sarkozy announced that the Irish must hold a second referendum. Before this took place, the economic situation in Europe had changed dramatically: in September 2008 in the USA there occurred the worst financial collapse since the Wall Street Crash of 1929 (see Section 27.7–8). The effects soon spread to Europe; by the end of 2008 the demand for European exports had contracted alarmingly, and one by one the member states of the EU plunged into recession. Worst affected were Spain and Ireland, the two countries which had enjoyed the highest growth rates in the EU since the introduction of the euro in 2002. As Perry Anderson explains:

The crisis struck hardest of all in Ireland, where output contracted by 8.5 per cent between the first quarters of 2008 and 2009, and the fiscal deficit soared to over 15 per cent of GDP. Though a probable death warrant for the regime in place at the next polls, in the short run the debacle of the Celtic Tiger was a diplomatic godsend to it. Amid popular panic the government could now count on frightening voters into accepting Lisbon, however irrelevant it might be to the fate of the Irish economy.

In October 2009 Irish voters obligingly approved the Lisbon Treaty, which came into effect on 1 December 2009.

(For further developments in the eurozone financial crisis,).

The future of the European Union

- All these problems should not be allowed to lead to the conclusion that the EU is a failure. Whatever happens in the future, nothing can take away the fact that since 1945, the countries of western Europe have been at peace with each other. It seems unlikely that they will ever go to war with each other again, if not absolutely certain. Given Europe’s war-torn past, this is a considerable achievement, which must be attributed in large measure to the European movement.

- However, the Union’s development is not complete: over the next half-century Europe could become a united federal state, or, more likely, it could remain a much looser organization politically, albeit with its own reformed and streamlined constitution. Many people hope that the EU will become strong and influential enough to provide a counterbalance to the USA, which in 2004 seemed in a position to dominate the world and convert it into a series of carbon copies of itself. Already the EU had demonstrated its potential. With the 2004 enlargement, the EU economy could rival that of the USA both in size and cohesion. The EU was providing well over half the world’s development aid – far more than the USA – and the gap between EU and US contributions was growing all the time. Even some American observers acknowledged the EU’s potential; Jeremy Rifkin wrote:‘Europe has become the new “city upon a hill”. … We Americans used to say that the American Dream is worth dying for. The new European Dream is worth living for.’

- The EU has shown that it is prepared to stand up to the USA. In March 2002 plans were announced to launch a European Galileo space-satellite system to enable civilian ships and aircraft to navigate and find their positions more accurately. The USA already had a similar system (GPS), but it was mainly used for military purposes. The US government protested strongly against the EU proposal on the grounds that the European system might interfere with US signals. The French president, Chirac, warned that if the USA was allowed to dominate space, ‘it would inevitably lead to our countries becoming first scientific and technological vassals, then industrial and economic vassals of the US’. The EU stood its ground and the plan went ahead. According to Will Hutton, ‘the US wanted a complete monopoly of such satellite ground positioning systems. … the EU’s decision is an important declaration of common interest and an assertion of technological superiority alike: Galileo is a better system than GPS.’

- Clearly the enlarged EU has vast potential, though it will need to deal with some serious weaknesses. The Common Agricultural Policy continues to encourage high production levels at the expense of quality, and causes a great deal of damage to the economies of the developing world; this needs attention, as does the whole system of food standards regulation. The confusing set of institutions needs to be simplified and their functions formalized in a new constitution. And perhaps most important – EU politicians must try to keep in touch with the wishes and feelings of the general public. They need to take more trouble to explain what they are doing, so that they can regain the respect and trust of Europe’s ordinary citizens. In a move which boded well for the future, the European parliament voted by a large majority in favour of José Manuel Barroso, the former prime minister of Portugal, as the next president of the European Commission. The new president had pledged himself to reform the EU, to bring it closer to its largely apathetic citizens, to make it fully competitive and to give it a new social vision. His five-year term of office began in November 2004 and in September 2009 he was granted a second five-year term.

- However, by that time the EU was facing two further problems: immigration and the deepening economic crisis. Increasing immigration into the EU, about half of which consisted of Muslims, led to racial and religious tensions; some observers were writing about the ‘battle at the borders’ to control and reduce the number of immigrants. By 2009 there were estimated to be between 15 and 18 million Muslim migrants in the richer western states of the EU. This might seem a small number out of a total population of perhaps 370 million, but what many people found worrying was that the birth rate among the native populations was declining, while that of the Muslims was increasing, especially in the big cities. In Brussels over half the children born every year were from Muslim immigrants. In Amsterdam there were more practising Muslims than either Protestants or Catholics. According to Perry Anderson, in 2009 the overall inflow of migrants into Europe was some 1.7 million a year.

- Poverty and unemployment in these communities is nearly always above the national average and discrimination pervasive. In a number of countries – France, Denmark, the Netherlands and Italy have been the most prominent to date – political parties have arisen whose appeal has been based on xenophobic opposition to it. The new diversity has not fostered harmony. It has stoked conflict.

- Given the wave of terrorism perpetrated by Muslim extremists during the first decade of the twenty-first century (see Section 12.2–3), it was hardly surprising that some observers talked about the impending war between Islam and the West. The problems of immigration and unemployment were linked: the optimistic view was that if and when the economy of Europe recovered and there was full employment, tensions would fade and Muslims and Christians would be able to live together in harmony – multiculturalism could triumph after all!

- However, in 2009, this seemed a forlorn hope – the crisis deepened and some economists were predicting that the euro was beyond salvation; some even thought the EU itself might disintegrate. In February 2012 Angela Merkel, the German Chancellor, said that Europe was facing its gravest test for decades, and she predicted that 2012 would be worse than 2011. All governments were trying to cut costs by introducing unpopular austerity measures. Greece had ‘manipulated’ its borrowing figures to make them look less than they actually were, in order to be allowed to join the euro (2001). The consequence was that Greek debts were enormous, and for much of 2011 and 2012 the government seemed to be on the verge of defaulting. This could have disastrous effects on banks and on the economies of other countries that had traded with Greece. Hungary’s currency, the forint, was in free fall, while Italy, Ireland, Spain and Portugal had huge debts and could only borrow more at high rates of interest. And everywhere unemployment was rising, averaging over 10 per cent throughout the EU.

|

50 videos|70 docs|30 tests

|