Agrarian Social Sturcture | Sociology Optional for UPSC (Notes) PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Evolution of Land Tenure System |

|

| Land Reforms |

|

| Objectives of Land Reforms |

|

| Land Reforms in India |

|

| Land Reforms After Independence |

|

| Impact of Land Reforms: An Assessment |

|

Evolution of Land Tenure System

Land management is the most crucial aspect of agrarian system and agrarian relations. Tenancy in agriculture land refers to leasing out land by an owner to a person who actually cultivates that land temporarily by his personal labour and pays rent in cash or kind to the owner. The owner, generally, has a subordinate interest in that land as he holds it as a matter of social status or to get an unearned income. As such, the owner is less interested in the improvement of the land as it is not the main source of his living. Such land tenure is far inferior to owner cultivator if we look at it from the viewpoint of tenant's interest.

If we look at the land tenure system in India we find that the land problem is a British legacy. The land structure served the colonial imperialist interests.

The main features of land structure in India in the pre-British period were:

- It was a self-reliant village economy where there was a system of barter exchange.

- The farmers produced enough to sustain and pay taxes to the extent of 1/ 8th of the produce.

- The function of the king was to collect taxes to protect the grain and provide proper transport of it from one place to the other (R.P. Dutt, 1979).

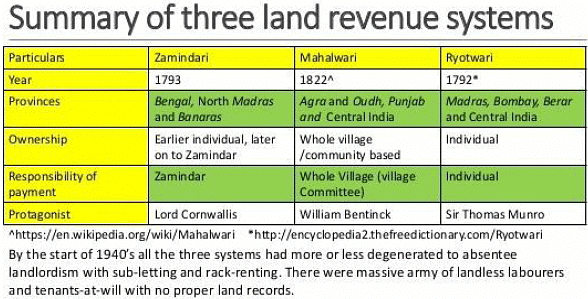

With the advent of the British rule, in broad terms, three types of land tenure system came to be established:

- Zamindari System: It refers to landlord's tenure. The landlords (Zamindars) were intermediaries between the government and the actual cultivators. This system came into being as a result of the East India Company making a huge payment to Mughal administration in 1765 for Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa where they became entitled to realise land revenue. Through permanent settlement in 1793, Lord Cornwallis gave land ownership to Zamindars who could give land for cultivation to anybody and evict one as per his wishes. He was obliged to pay taxes to the government. There were no cultivating owners of land. Zamindari system was run under two types of settlement: (a) Permanent settlement and (b) Temporary settlement. Under the former the land revenue used to be fixed for a long duration while under the later it was for a shorter duration after which the land revenue could always be enhanced. In political terms the Zamindars became their collaborators and stooges of the British.

- Ryotwari System: It refers to an independent single tenure. Initially this system was promulgated by Thomas Munroe in 1792 for Madras but gradually expanded to Bombay, Central Provinces, Assam, Coorg, etc. Under Ryotwari system the ryot or the registered holder of land was recognised as holding the land directly from the government without any intermediaries. His tenure was 'occupancy tenure' and he continued to be landowner as long as he was paying land revenue to the government. Under this system, land settlement used to be determined by the government as per the fertility of the land for a period varying between 20 to 30 years and on that basis land revenues were collected.

- Mahalwari System: It refers to joint village or village community tenure system and was first introduced in Agra and Oudh Provinces in 1833. Later it was extended to Punjab and parts of Central Provinces. Under this system the, whole mahal (village) was vested with land ownership. The communal ownership of land by the entire village community was the basis of this system. The Numberdaar (village headman) was responsible to, collect maalguzari (tax) and deposit it in the government treasury. The wasteland, trees, wells and ponds etc. were common property resources of the entire village community.

With the advent of independence a number of measures were taken to reform land holding structure and land relations. In fact Indian National Congress, spearheading the freedom movement, was committed to eliminate the intermediary parasites and absentee landlords. Though the aspirations of the tiller of the soil could never be fulfilled totally, yet the agrarian structure underwent important changes. Various measures of land reforms unleashed numerous forces of change.

Land Reforms

- Agrarian structure forms a critical aspect of any discussion on socio-economic development in India. The issues of economic backwardness and rural tension are all involved in the basic nature of an agrarian society. Land continues to be the mainstay of the people. It constitutes not only the structural feature of rural areas but changes in land relations act as significant indicator of social and economic change.

Concept of Land Reforms

- The term land reform has been used both in a narrow and in a broad sense. In the narrow and generally accepted sense, land reform means redistribution of rights in land for the benefit of small farmers and landless people. This concept of land reform refers to its simplest element commonly found in all land reform policies. On the other hand, in a broad sense land reform is understood to mean any improvement in the institutions of land system and agricultural organisation. This understanding of and reform suggests that land reform measures should aim not only for redistribution of land but also undertake other measures to improve conditions of agriculture. The United Nations has accepted this notion of land reform. The UN definition says that the ideal land reform programme is an integrated programme of measures designed to eliminate obstacles to economic and social development arising out of defects in the agrarian structure.

- In the present context also, by land reforms we mean all those measures which have been undertaken in India by the government to remove structural anomalies in the agrarian system.

Objectives of Land Reforms

While there are no universal motives behind land reforms, some common objectives can be observed in various contexts.

Social Justice and Economic Equality

- One of the primary objectives of land reforms is to achieve social justice and economic equality. The concept of equality has become ingrained in modern consciousness, especially in traditional hierarchical societies where it is seen as a revolutionary force.

- Land reforms aim to eliminate discrimination and poverty, reflecting the ideology of equality and social justice through initiatives like land reforms and poverty alleviation.

Nationalism

- Nationalism has historically motivated land reforms, particularly in developing countries that gained independence after World War II.

- Land reforms were seen as a means to dismantle colonial structures, such as large estates owned by foreign nationals and exploitative land tenures like the Zamindari system established during British rule.

- The abolition of the Zamindari system, a symbol of colonial exploitation, became a key goal of the early land reform measures post-independence.

Democracy

- The desire for democracy has also driven land reform programs. Democracy is viewed as essential for achieving liberty and justice, allowing even the poor and marginalized to express their grievances and demands.

- In this context, land reforms are seen as a way to create an environment conducive to democratic expression and participation.

Increasing Agricultural Productivity

- Land reforms are considered crucial for increasing agricultural productivity and are central to economic development in agricultural societies.

- By addressing issues of agrarian reorganization, land reforms aim to enhance productivity and contribute to overall economic development.

Land Reforms in India

Land reforms in India were initiated due to a combination of political factors and the organization and mobilization of the peasantry. The political factors were rooted in British rule and the subsequent rise of nationalism, creating a context in which land reform became a necessity for the government.

- Early agrarian legislation aimed at protecting the rights of tenants dates back to the mid-nineteenth century.

- The extreme poverty of the people and the exploitation of peasants by Zamindars and moneylenders caught the attention of political leaders during the freedom struggle.

Pre-Independence Era

- Peasant Struggles: The period before independence saw a rise in peasant struggles across the country, with various movements highlighting the grievances of middle and poor peasants.

- All India Kisan Sabha: In 1936, the All India Kisan Sabha, a prominent peasant organization, called for the abolition of Zamindari, occupancy rights for tenants, and redistribution of cultivable waste land to landless laborers.

- Peasant Organizations: Between 1920 and 1946, several peasant organizations emerged, advocating for the rights and interests of peasants. Movements like the Kisan Sabha Movement, Kheda Agitation (1918), Bardoli Satyagrah (1928), and Tebhaga Movement (1947) in Bengal were significant in expressing agrarian discontent.

- Government Response: The widespread discontent and conflicts between peasants and landlords prompted the government to address the grievances of peasants. The pressure from these pre-independence struggles played a crucial role in shaping the land reform programs that would be implemented after independence.

Post-Independence Era

- Constitutional Framework: After gaining independence, India adopted a Constitution that provided the legal basis for land reforms.

- Land Reforms: Various agrarian reforms were implemented to address the issues identified during the freedom struggle. This included the abolition of Zamindari and measures to secure tenant rights.

- Political Consensus: The political climate post-independence favored land reforms, with a broad consensus on the need to address agrarian issues.

- Implementation of Reforms: The government took steps to implement land reforms, including the distribution of land to the landless, securing rights for tenants, and promoting cooperative farming.

- Long-Term Goals: The land reform programs aimed at long-term goals of social justice, economic equality, and increased agricultural productivity.

Role of Peasant Movements

- The peasant movements before independence played a significant role in shaping the agenda for land reforms post-independence.

- Their activism and demands set the stage for the government to prioritize agrarian issues and implement reforms aimed at addressing the grievances of the peasantry.

In summary, land reforms in India were a response to historical grievances, political pressures, and the aspirations of the peasantry. The movements before independence created a foundation for the reforms that aimed to address agrarian injustice and promote social equity in the post-independence era.

Land Reforms After Independence

After gaining independence, the Indian government placed significant emphasis on land reforms as a crucial part of its national policy aimed at transforming the inequitable agrarian structure inherited from the colonial period. The strategy involved implementing land reforms through legislative measures, as broadly indicated by the Government of India and enacted by various state legislatures.

Objectives of Land Reforms

- The primary objectives of land reforms were twofold:

- To eliminate motivational and structural impediments from the inherited agrarian system.

- To eradicate exploitation and social injustice within the agrarian framework, ensuring equality of status and opportunity for all sections of society.

These objectives reflected a commitment to modernizing agriculture and reducing inequalities within the agrarian economy. The government translated these objectives into specific programmes of action.

Key Programmes of Action:

- Abolition of Intermediaries: One of the first targets of land reforms was the abolition of intermediaries such as Zamindars, Jagirdars, and Mirasdars who had been established during British rule. The British introduced land settlement systems like Zamindari, Raiyatwari, and Mahalwari to maximize revenue from land.

- Under the Zamindari system, local rent collectors (Zamindars), often from upper-caste communities, were given property rights over land, turning actual cultivators into tenants. This created an intermediary layer between the state and the tillers of the soil.

- In the Raiyatwari system, no intermediaries were recognized, and actual tillers were given transferable rights to their land. However, powerful Raiyats still emerged as significant landholders.

- The Mahalwari system also led to the emergence of intermediaries.

- These intermediaries had little interest in land management or improvement. While Zamindars paid a fixed revenue to the government, there was no limit on the collections from actual cultivators, leading to exploitation through illegal cesses.

- The Zamindari system also allowed for absentee ownership, making it unjust and exploitative.

- In response to this historical context, the abolition of intermediary interests became a priority in the early years of independence. This reform aimed to eliminate intermediaries and establish a direct relationship between cultivators and the state.

- Tenancy Reforms: Tenancy, the practice of renting land for cultivation, was widespread in various forms such as sharecropping, fixed-kind produce, and fixed-cash arrangements. These systems existed in both Zamindari and Raiyatwari areas.

- Legislations in almost all states restricted the size of land holdings that a person or family could own, with variations based on land quality. Acquisition of land beyond the ceiling was prohibited, and surplus land was taken over by the state for redistribution among weaker sections of society.

- While land ceiling laws were enacted following the central government’s framework, there were significant differences among state laws regarding the ceilings and exemptions.

- Ceiling limits varied, with some states imposing very high ceilings and others allowing manipulation by landowners. The process of taking possession of surplus land and its distribution was often slow.

- By September 2000, a total of 73.49 lakh acres of land had been declared surplus across the country, with 64.84 lakh acres taken possession of and 52.99 lakh acres distributed. The beneficiaries of this scheme included 55.10 lakh individuals, with 36% from Scheduled Castes and 15% from Scheduled Tribes.

In summary, land reforms after independence aimed to address historical injustices in land ownership and tenancy, promoting direct relationships between cultivators and the state while reducing inequalities in land distribution.

Consolidation of Holdings

- The fragmentation of landholdings has been an important impediment in agricultural development. Most holdings are not only small but also widely scattered. Thus, legislative measures for consolidation of holdings have been undertaken in most of the states. Major focus has been on the consolidation of the land of a holder at one or two places for enabling them to make better use of resources. Attempts have also been made to take measures for consolidation in the command areas of major irrigation projects.

Land reforms sought to eliminate exploitation and social injustices within the agrarian system

Land reforms sought to eliminate exploitation and social injustices within the agrarian system

Land Records

- The record of rights in land has been faulty and unsatisfactory. The availability of correct and up-to-date records has always been a problem. It is in view of this that updating of land records has been made a part of land reform measures.

- However, progress in this respect has been poor. The Five Year Plan documents say that in several states, record of right do not provide information regarding tenants, sub-tenants and crop-sharers. It has further been highlighted that large areas of the country still do not have up-to-date land records. The main reason behind this has been the strong opposition of big landowners.

- Nonetheless several states have initiated the process of updating the land records through provisional surveys and settlements. Steps have also been taken to computerise these records. A centrally sponsored scheme on computerisation of land records has been launched with a view to remove the problems inherent in the manual system of maintenance and updating of land records.

Impact of Land Reforms: An Assessment

Ensuring Redistribution of Land

- Agricultural land ceiling laws are a prominent aspect of land reforms in India.

- These laws set limits on the amount of land an individual or family can own, aiming to redistribute excess land to the landless, marginal, and poor farmers.

- The implementation of ceiling laws occurred in two phases:

- Phase I (1960-1972): No specific guidelines were in place.

- Phase II (1972 onwards): National guidelines were adopted.

- By 2002, approximately 5.4 million acres of land had been redistributed to 5.6 million households. West Bengal accounted for 20% of this redistributed land.

- The ceiling laws also helped prevent the concentration of landownership, as reflected in the decline of land in the largest size class over time.

Land Reforms and Reduction of Poverty

- Poverty reduction and literacy are linked to land reforms.

- Studies indicate a strong connection between poverty reduction and land reforms, especially tenancy reform and abolition of intermediaries.

- Land reform can benefit the landless by increasing agricultural wages.

- Even partial reforms impacting agricultural production relations can significantly reduce rural poverty.

- Successful land reforms in states like West Bengal and Kerala demonstrate positive impacts on poverty and literacy.

- West Bengal: Prioritized distributing small plots of ceiling-surplus land to numerous landless families, leading to increased food consumption, income, and social status.

- Kerala: The Land Reforms Act 1969 granted ownership rights to cultivating tenants and homestead rights to hutment dwellers, contributing to higher literacy rates and improved health indicators.

Failures and Challenges

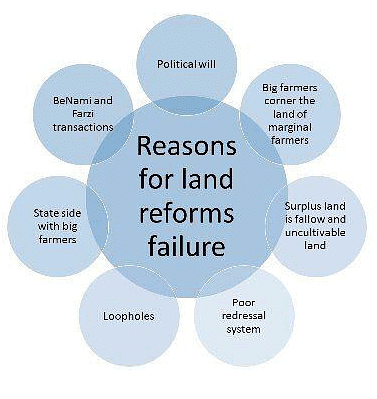

- Many states faced challenges in implementing land reforms due to political will and incomplete legislation.

- In Kerala, the exclusion of plantations from land reforms and ineffective ceiling act implementation hindered outcomes.

- The Planning Commission of India(1973) criticized land reform programs for failing to significantly change agrarian structures due to lack of political will.

- In Uttar Pradesh, land reforms dispossessed landlords, but did not significantly redistribute land to the rural poor.

- Bihar faced legal and political obstacles to achieving deep changes in land ownership patterns.

- Land reforms often led to mass eviction of tenants and passive dispossession of the poor.

- Tenant families were evicted from agricultural land due to tenancy reform legislation.

- Land consolidation faced challenges due to land quality differences and power dynamics favoring richer farmers.

- Land consolidation was successful in states like Punjab,Haryana, and to some extent,Uttar Pradesh, but struggled in states like Madhya Pradesh,Gujarat,Rajasthan, and Karnataka.

- Proletarianization occurred as beneficiaries of land reforms, primarily from upper and middle castes, faced economic challenges and joined the ranks of agricultural laborers.

- Land reforms aimed at economic development and social justice but ended up benefiting peasant proprietors more than the rural poor.

- The reforms led to the emergence of new landed classes and medium landowners who gained political power and economic control.

- Women were often excluded from land reforms, and increasing men's bargaining power alone did not improve conditions for women agricultural laborers.

- Land reform aimed at improving bargaining power for rural poor but did not address the specific needs of women laborers.

- Women's ownership of land is crucial for stimulating their labor and investment and for flexibility in farm resource management.

Conclusion

- Thus, land reforms in India have had a mixed record. They had been envisaged as a tool through which the state would directly intervene to improve the conditions of large masses of the rural impoverished poor, who had very low bargaining power in society. The first phase of land reforms in the early 60s was left to the states. But initial enthusiasm for land reform abated because India faced a massive food crisis in the decade of the 1960s and the state’s attention had to be directed towards productivity enhancing measures like the Green Revolution.

- The rising tide of rural unrest in the form of Naxalism in different states forced the government to think of land reforms again and national guidelines were formulated in 1972 regarding reducing land ceilings, introducing family based ceiling on land, tenancy reform and other such similar measures.

- Almost a decade later a review undertaken as part of the Sixth Five Year Plan found that land reforms had failed to achieve its goals due to the lack of the political will of the State. In fact, P. S Appu, a long-time observer of land reforms opines that the successful abolition of intermediary interests as against the near- complete failure of tenancy reform and land ceiling legislation and redistribution of ceiling-surplus land has been largely a reflection of the class character and democratic political structure of the post-colonial Indian state and state power.

- The Seventh Five Year Plan (1985-90) reiterated land reform to be the core of the anti-poverty program of the state and integrated it with mainstream rural development activity. But with globalization and the ushering in of neo-liberal reforms land reforms have become a forgotten agenda of state policy. Market based land reforms were introduced with key financial and technical support of the international agencies and banks which ultimately did not benefit the poor as they were unable to access land.

- The rural sector in India today is marked by simmering unrest due to the land acquisition policies of the government which favours the industry. While we witness a gradual shift towards land markets, India is still left with the persistence of a land question.

|

139 videos|428 docs

|

FAQs on Agrarian Social Sturcture - Sociology Optional for UPSC (Notes)

| 1. What are the key features of the traditional land tenure system in India? |  |

| 2. How has the land tenure system evolved post-independence in India? |  |

| 3. What impact did the Green Revolution have on land tenure systems in India? |  |

| 4. How do land tenure systems affect agricultural productivity and social relations in rural India? |  |

| 5. What are the contemporary challenges faced by land tenure systems in India? |  |