Tribal Communities in India - UPSC PDF Download

Definitional Problems

- What is a tribe? What exactly are the criteria for considering a human group, a tribe? What are the indices of the tribal life?

A woman belonging to the Ao tribe in Nagaland

A woman belonging to the Ao tribe in Nagaland - Interestingly but sadly the anthropologists, sociologists, social workers, administrators and such people who have been involved with the tribes and their problems either on theoretical plane or on practical grounds are still not on the same wavelength regarding the concept and the definition of their subject matter. Arthur Wilkes, et al (1979) puts the problem in proper perspective by stating that for years ambiguity has stalked India's official portrait of tribal people. From 1917 through the 1931 Census, for instance, the nomenclature referring to tribes underwent successive modifications, involving primarily changes in descriptive adjectives such as "aboriginal" or "depressed classes". By the 1941 Census, these qualifying adjectives were dropped, a practice continued after independence with the adoption of the notion of scheduled tribes or as they are commonly called, Adivasi. Such standardization did not however remove all ambiguity.

- No doubt with the passage of time, the differences on the concept and definition of a tribe have certainly narrowed down to an appreciable extent, but a theoretical discussion seems imperative to understand this problem in its proper perspective.

- Here are a few definitions of tribe being used as the basis of discussion in the present chapter:

A tribe is a collection of families bearing a common name, speaking a common dialect, occupying or professing to occupy a common territory and is not usually endogamous, though originally it might have been so. -Imperial Gazetteer of India - A tribe is a group of people in a primitive or barbarous stage of development acknowledging the authority of a chief and usually regarding themselves as having a common ancestor. - Oxford Dictionary

- A tribe is a collection or group of families bearing a common name, members of which occupy the same territory, speak the same language and observe certain taboos regarding marriage, profession or occupation and have developed a well assigned system of reciprocity and mutuality of obligation. - D.N. Majumdar

- In its simplest form the tribe is a group of bands occupying a contiguous territory or territories and having a feeling of unity deriving from numerous similarities in culture, frequent contacts, and a certain community of interest. - Ralph Linton

- A tribe is an independent political division of a population with a common culture. - Lucy Mair

- A tribe is a group united by a common name in which the members take pride, by a common language, by a common territory, and by a feeling that all who do not share this name are outsiders, enemies in fact. - G.W.B. Huntingford

- A tribe is a social group with territorial affiliation, endogamous, with no specialization of functions, ruled by tribal officers, hereditary or otherwise, united in language or dialect, recognizing social distance with other tribes or castes, without any social obloquy attaching to them (as it does in the caste structure), following tribal traditions, beliefs and customs, not receptive to ideas from alien sources, above all conscious of homogeneity of ethnic and territorial integration.

- Ideally, tribal societies are small in scale, are restricted in the spatial and temporal range of their social, legal, and political relations, and possess a morality, a religion and world view of corresponding dimensions. Characteristically too, tribal languages are unwritten, and hence the extent of communication both in time and space is remarkable economy of design and have a compactness and self sufficiency lacking in modern society.

- Majumdar and Madan (1967) rightly comment that where one looks into the definitions given by various anthropologists, one is bound to be impressed by the dissimilarity of their views as regards what constitutes a tribe. Kinship ties, common territory, one language, joint ownership, one political organization, absence of internecine strife have all been referred to as the main characteristics of a tribe. Some anthropologists have not only accepted some of the characteristics, but have also stoutly denied some of them to be characteristics of a tribe. Thus, Rivers did not mention habitation in a common territory as a vital feature of tribal organization, although others like Perry have insisted on it, saying that even nomadic tribes roam about within a definite region. Radcliffe - Brown has given instances of one section of a tribe fighting another from his Australian data. The only conclusion one can draw from such diversity of learned opinion is that the views of each anthropologist arise from the type of data with which he is most familiar. One may, therefore, make a list of universal characteristics, some of which would define a tribe anywhere. Thus, Majumdar claims universal applicability of his definition given earlier.

- A major hurdle of defining a tribe is that related with the problem of distinguishing the tribe from peasantry. It is not possible to use the labels 'tribal' and 'peasant' for this type of social organisation and to characterize one by contrasting it with the other. But in spite of all the effort invested by anthropologists in the study of primitive societies, there really is no satisfactory way of defining a tribal society. What this amounts to in the Indian context is that anthropologists have tried to characterise a somewhat nebulous sociological type, by contrasting it with another, which is almost equally nebulous. Earlier anthropologists had not paid sufficient attention to define tribal society, but tacitly assumed that what they were studying in Australia, Malaysia and Africa were various forms of tribal society. The tribe was somewhat vaguely assumed to be a more or less homogeneous society having a common dialect and a common culture (Andre Beteille, 1973). Though not everybody will agree with the assumption of Beteille but his statement may be cited as one of the many schools of thought grappling with the problem.

- The above discussion shows that it is not easy to define a tribe or a tribal society conclusively and any standardisation in this regard is very difficult to obtain. Hence, it will be better to shy away from international or universal plane keeping in view the regional connotation of the concept of tribe. Instead, we should focus attention on gaining standardization within the Indian universe to solve our own problems. This seems to be quite sensible in the situation when definitions of universal applicability are either very broad and loose or very narrow and restricted. In this context Andre Beteille aptly remarks that Bailey is perhaps the only anthropologist working in the Indian field who has tried to characterize tribes in terms of segmentary principles, but the contrast in which he is interested is not between tribe and peasant but between tribe and caste. Further, unlike Bailey, the majority of Indian anthropologists have not given much serious thought to the problem of creating a definition of tribal society which will be appropriate to the Indian context.

- Now let us examine the problem specifically in the Indian context. T.B. Naik (1960) raises the problem in proper perspective by talking of the criteria and indices of the tribal life in specifically Indian setting. What should be the criteria and indices of tribal life? Living in forest? The Dublas of Surat and a host of others do not live in forests. They live in fertile plains; nevertheless they are included in the Scheduled Tribes. Primitive religion? But you do not know what primitive religion is in India, there being a continuance from the most abstract philosophy to the tribal gods and superstitious beliefs in the religion of most of the advanced communities of India. This index being very fluid and not exact will not do. Geographical isolation? There are hundreds of tribal groups who are not living an isolated life. Primitive economic system? There are many peasant groups who are living by an equally primitive economic system. Thus, Naik goes on to present his own criteria for a tribe which are as follows:

- A tribe to be a tribe should have the least functional inter dependence within the community (the Hindu caste system is an example of high interdependence)

- It should be economically backward which means:

- the full import of monetary economics should not be understood by its members

- primitive means of exploiting natural resources should be used.

- the tribe's economy should be at an underdeveloped stage; and

- it should have multifarious economic pursuits.

- There should be a comparative geographic isolation of its people from others.

- Culturally, members of a tribe should have a common dialect, which may be subject to regional variations.

- A tribe should be politically organized and its community Panchayat should be an influential institution.

- The tribe's members should have the least desire to change. They should have a sort of psychological conservatism making them stick to their old customs.

- A tribe should have customary laws and its members might have to suffer in a law court because of these laws.

Naik further elaborates that a community to be a tribe must have all these attributes. It might be undergoing acculturation; but the degree of acculturation will have to be determined in the context of its customs, gods, language, etc. A very high degree of acculturation will automatically debar it from being a tribe.

Prof. Ehrenfels elaborates the points already discussed above by saying that:

- A tribe is a community, however small it may be, remaining in isolation from the other communities within a geographical region. This applies to a caste as well as to a tribe. The members of a true tribe, however, are generally not included into the traditional Hindu caste hierarchy and frequently speak also a common dialect , entertain common beliefs, follow common occupational practices and (most important) consider themselves as members of a small but semi national unit.

- I would delete in the above (Naik’s) definition the words "economically backward", "primitive means" and "underdeveloped stage" and substitute them by the words "self sufficient" (for example Khasi, Gond, Bhil, Agaria and others who are in part more specialized economically, even much more than their non tribal neighbours). Yet each individual of a tribe may work for his family group and thus may remain functionally dependent of solidarity with the tribe as a whole, rather than as a partner in the caste hierarchy of non-tribal Hindus.

- I agree with the definition of geographical isolation though not every tribe is an isolated unit of people (e.g., Bhil, Santhals, Irula, etc.). But if a tribe has its own system of economy, its isolation will no doubt be more stable.

- Common dialects or languages are typical for tribes in Assam and the Central areas, but not in the southern and western states of India. Community of language helps greatly, but is not imperative for building up tribal consciousness. The original religious concepts of most tribes in pre-acculturation days were different from their Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim or Christian neighbours but are not always so now.

- A tribe need not always be politically organized nor have a community Panchayat. It may or may not have a single chief or a few elders who may wield more or less power within the community.

- I would delete the relevant para of the above and substitute it with the words, "The members of a tribe have a feeling of belonging to a group the existence of which is valuable".

- Almost all tribes have customary laws and practices, more or less different from their non-tribal neighbours. Very often they are indeed made to suffer on this account in law courts and in other contact situations with non tribals.

The Tata Institute of Social Sciences in its report on the Indian tribes has also joined those who have been criticizing the anthropologist's approach of the problem. It says that (anthropological) criteria apply to ideal typical tribal communities as conceived by the anthropologists for theoretical purpose. These do not appear to be empirically related to communities that have been included in the list of the scheduled tribes. The logical implication seems to be that communities which do not satisfy the above criteria should not be considered as tribes even though they are included in the list of the scheduled tribes. Arthur Wilke et al (1979) too, like some others, opine that some measure, if not a substantial measure, of the difficulty is inherent in the intellectual legacy of the discipline of anthropology.

Aiyappan, provoked by such statements remarks rather sceptically, reminding us of the well-known definition given by Tate Regan of 'species'. Adopting the definition, Aiyappan said that “a tribe is a group which a competent anthropologist considers to be a tribe.” If the Administrator wants a clear cut definition which he can apply blindly and get along with, he says, we should tell him that we don't have it, just as the zoologist is not in a position to give a clear cut all-purpose definition of species.

Despite such rhetoric and academic polemics on the problem of definition of tribe quite a substantial measure of standardization has been accomplished in designating which people are or are not entitled to particular protection and privilege. This could become possible only due to vigorous academic efforts of the much maligned and misunderstood anthropologists who, with the help of rigorous and painstaking empirical research, ultimately came out with definite and empirically verifiable ethnographic data to clear the cobwebs of misgivings regarding Indian tribes.

Majumdar and Madan (1967) demonstrate this new mood by emphatically stating the following facts:

- In India, a tribe is definitely a territorial group, a tribe has a traditional territory, and emigrants always refer to it as their home. The Santhals working in the Assam tea gardens refer to particular regions of Bihar or Bengal as their ‘home’.

- All members of a tribe are not kin of each other, but within every Indian tribe kinship operates as a strong associative, regulative and integrating principle. The consequence is tribal endogamy and the division of a tribe into clans and sub-clans and so on. These clans, etc, being kin groups, are exogamous.

- Members of an Indian tribe speak one common language - their own or that of their neighbours. Intra tribal conflict on a group scale is not a feature of Indian tribes. Joint ownership of property, wherever present as for instance among the Hos, is not exclusive. Politically, Indian tribes are under the control of the state governments, but within a tribe there may be a number of Panchayats (tribal councils) corresponding to the heterogeneity, racial and cultural, of the constituent population in a village or in adjacent villages.

- There are other distinguishing features of Indian tribes. Thus, there are their dormitory institutions, the absence of institutional schooling for boys and girls, distinctive customs regarding birth, marriage, and death, a moral code different from that of Hindus and Muslims, peculiarities of religious beliefs and rituals which may distinguish tribesmen even from the low caste Hindus.

To wind up this discussion it seems to be quite apt to refer to Arthur Wilke et al (1979) who opine that when the constraints of bureaucratic decision-making and administration reign supreme, there is a tendency to gloss over the rich and at times puzzling mosaic of human affairs. What accounts for indetermination in the concept of tribe is likely that the dictates of bureaucratic procedures and the unceasing acculturation going on throughout India and particularly among many identified tribal people make it difficult to apply an idea which is in many respects, an ideal type formulation.

Due to multiplicity of factors and complexity of problems involved, it is not very easy to classify the Indian tribes into different groups. However, the Commissioner for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes took up the task and investigated the possibility of adopting classification criteria. Keeping this aim in view the state governments were asked to suggest the characteristics which seemed to them most suitable in distinguishing the so called aboriginal groups from the rest of the population.

The Assam government suggested descent from Mongoloid stock, affiliation with Tibeto-Burman linguistic groups and the existence of a social organization of the village clan type as the major characteristics. The erstwhile Bombay government considered residence in forest areas as the basic criterion while for the Madhya Pradesh government tribal origin, speaking tribal language and residence in forest areas were important criteria. Similarly, the governments of Madras, Orissa, Andhra, Mysore, Travancore, etc., suggested various linguistic, geographical, economic and social factors as indicators:-

Taking the above mentioned characteristics into consideration the tribes basis of India may be classified on the basis of their

(a) territorial distribution,

(b) linguistic affiliation,

(c) physical and racial characteristics,

(d) occupation or economy,

(e) cultural contact and

(f) religious beliefs.

Geographical Spread

Looking at the physical map of India and the distribution of tribal population, we find that both geography as well as tribal demography permits a regional grouping and a zonal classification. B.S. Guha has classified Indian tribes into three zones.

(i) The North and north eastern zone

(ii) The central or the middle zone

(iii) The southern zone

- The northern and north-eastern zone: The northern and north-eastern zone consists of Sub Himalyan region and the mountain valleys of the eastern frontiers of India. The tribal people of Assam, Manipur and Tripura may be included in the eastern part of this geographical zone while in the northern part are included the tribal of eastern Kashmir; eastern Punjab, Himachal Pradesh and northern Uttar Pradesh. Some of the important tribes living between Assam and Tibet are Aka, Dafla, Miri, Gurung and the Apatani on the west of the Subansiri river. The Mishmi tribes live in the h igh ranges between the Debong and Lohit river. Further east are found the Khamti and the Singpho and beyond them are the different Naga tribes. South of the Naga Hills running though the states of Manipur, Tripura and the Chittagong hill tracts live the Kuki, the Lushai, the Khasi and the Garo (now the habitants of the Meghalaya state). The Himalayan region of Uttar Pradesh also contains some important tribes like Tharu, Bhoks, Jounsari (Khasa), Bhotia, Raji, etc.

The entire geographical zone, though quite large in area, does not contain dense tribal population. As a result of geographical conditions most of the tribes of this zone are engaged in either terrace cultivation or Jhum (shifting) cultivation and are steeped in poverty and economic backwardness. - The Central or the Middle Zone: This zone consists of plateaus and mountainous belt between the Indo -Gangetic plain to the north and roughly the Krishna river to the south and this is separated from the north eastern zone by the gap between the Garo hills and the Rajmahal hills In this zone we have another massing of tribal peoples in Madhya Pradesh with extensions in Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Bharat, southern Rajasthan, northern Maharashtra, Bihar and Orissa. Northern Rajasthan, southern Maharashtra and Bastar form the peripheral areas of the zone. The important tribes inhabiting this zone are the Savara, Gadaba and Borido of the Ganjam district; the Juang, Kharia, Khond Bhumij and the Bhuiya. On the plateau of Chotanagpur live Munda, Santhal, Oraon, Ho and Birhor. Further west along Vindhya ranges live the Katkari, Kol and Bhil. The Gonds form a large group and occupy what is known as the Gondwanaland. On both sides of the Satpuras and around the Maikal hills are found similar tribes like Koraku, Agaria, Pardhan and Baiga. In the hills of Bastar live some of the most colourful of these tribes like Muria, the Hill Muriya of the Abhujmar hills and Bison horn Maria of the Indravati valley. Most of the tribes of this zone practice shifting cultivation as means of their livelihood but the Oraon, Santhal, Munda and Gond have learnt plough cultivation as a result of their cultural contact with neighbouring rural populations.

- The Southern Zone: This zone consists of that part of southern India, which falls south of the river Krishna stretching from Waynaad to Cape Camorin. Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Coorg, Travancore, Cochin, Tamil Nadu, etc., are included in this zone. Beginning from the north east of this zone, the Chenchu occupy the area of the Nallaimallais hills across the Krishna and into the erstwhile Hyderabad state. Along the Western Ghats from the Loranga of South Kanara, the Yeruva and the Toda live on the lower slopes of Coorg hills while the Irula, Paniyan and the Kurumba inhabit Wynaad area. The most primitive of Indian aboriginals such as Kadar, Kanikkar, Malvadan, Malakuravan, etc., inhabit the dense forests along the ranges of Cochin and Travancore. They are also included among some of the most economically backward communities of the world. Except Toda, Badaga and Kota who live in Nilgiri hills most of the tribal groups of this zone depend upon hunting and fishing for food.

Although Guha has not included the inhabitants of Andaman and Nicobar Islands in any of these zones and has skipped their description, yet these tribal people may be said to constitute a fourth zone. The main tribes living in this zone are the Jarwa, Onge, North Sentinelese, Andamanese and Nicobari. Thus separated from the main body of India's primitive tribes, they are ethnically close to the south Indian tribes.

Colonial Policies And Tribes

- The Britishers came into contact with the tribes during their efforts for the consolidation of the Indian Empire. Quite early they had to control the turbulent Hill Paharia of the Rajmahal Hills (Bengal) who had risen in revolt against the Hindu Zamindars. They were at first subdued in a clash of arms, but soon after a policy of pacification was decided upon. Bribes were paid, under the name of pensions and totalling Rs. 15,000 per year, to tribal leaders. Ex servicemen were encouraged to settle down around the Paharia habitation. In 1782, on the suggestion of Augusts Cleaveland, administrator of the area Rajmahal Hills were withdrawn from normal administration. Local courts, consisting of local leaders, were given civil and penal jurisdiction over the Hills tract. Contacts with Zamindars were severed and the Paharia held rent free land direct from the government. Thus were laid the foundations of the British policy towards the tribes which in the course of the next 125 years developed into a policy of laissez faire and of segregation of tribal areas combined with a harsh application of the laws of the land, entirely unsuited to the tribes. British policy was, in short, a hotch potch of segregation, often unnecessary and harmful and lack of discrimination or unfair discrimination in administration, both of which hit the tribes hard. The Criminal Tribes Act which enhanced ordinary punishments provided in the Penal Code was one such example of unfair discrimination against the tribes. It has fortunately been repealed by the national government.

- Resuming our account of Paharia administration, under the guidance of Cleveland and his successors a Hill Assembly was formed not only to administer justice but also frame rules for its own procedure for conducting the affairs of the tribe. In 1796 these rules were made Regulation I of that year by the government. But the experiment did not succeed over time. Inefficiency and corruption crept in, and in 1827 Regulation I of 1796 was abolished. Instead a new Regulation I of 1827 brought the Paharia and other adjacent tribes under the partial jurisdiction of ordinary courts, providing special exemptions from the application of the law in their favour.

- Such remained the pattern for the administration of the tribes till 1855 when the Santhal rose in revolt. In non-regulation areas Regulation was reintroduced giving civil and penal powers to executive officers in the affected areas which thus came under a special administration. The British Parliament sanctioned the establishment of specially administered non-regulation areas by the Indian Councils Act of 1861. In 1870, the Parliament gave the Governor General in Council the power to legalize the regulations under which various areas were being specially administered. The Scheduled Districts Act, XIV of 1874, passed by the Indian legislature, gave special powers to local government. A local government could now specify the enactments that were to be locally in force in a specially administered area; and the modifications which were to be made in enactments, elsewhere in force, before their application to a specially administered area.

- With various local modifications, the pattern of British policy remained as outlined in the foregoing paragraphs till Parliament passed the Government of India Act, 1919. Under section 52- A (2) of this Act special modified administration of various areas, regarded as backward, could be ordered by the Governor-General in Council, thus wholly exempting the people of the said areas from administration under provisions of the Act. It was felt by the Government of India that whereas in certain backward areas modification of national laws was enough, in certain other such areas complete special administration alone would meet the demands of the situation. Thus came into existence partially and wholly excluded areas. Further, some excluded areas were not given the right of representation in the Indian and provincial legislature, others could have members nominated on their behalf; and still others could elect some of their representatives, while the rest would have to be nominated to represent them.

- The application of the Government of India Act, 1935, brought about some minor changes. The Council of Ministers could not advise a governor on how to administer a wholly excluded area. But the application of the provisions of the Act by popular ministries with regard to partially excluded areas resulted in the appointment of tribal inquiry committees in several states like Bihar, Orissa, Bombay, and Madras. Till then British policy had been a negative one. Its sole aim was to let the tribes live (and that meant also, be exploited) so long as they did not cause trouble. The appointment of inquiry committees was the first step towards a positive policy of reconstruction. Problems can be solved only after they are assessed, and here was assessment being ordered to shape its future policies. But the War brought with it the resignation of popular ministries and a national emergency, preventing any new policy for tribal rehabilitation from taking shape.

Issue of Integration And Autonomy

- For thousands of years primitive tribes persisted in forests and hills without having more than casual contact with the populations of the open plains and the centres of civilization. Now and then, a military campaign extending for a short spell into the vastness of tribal country would bring the inhabitants temporarily to the notice of princes and chroniclers, but for long periods there was frictionless co -existence between the tribal folks and Hindu caste society in the truest sense of the word (Haimendorf, 1960). But the physical isolation of most of the aboriginal tribes drew to an end when the modern means of communication like railways and roads were introduced in the nineteenth and early twentieth century coupled with the sudden growth of India's population. This caused land hungry peasants of the plains to invade the sparsely populated tribal regions of middle and south India. Moreover, the extension of law and order to the areas which in earlier days had been virtually unadministered - enabled traders, moneylenders and a host of administrators, social workers, etc. - to establish themselves in tribal villages.

- The onslaught of moneylenders and traders from the plains played havoc with the tribals who, as many examples show, lost their economic independence and lot of land within a span of twenty to thirty years of their contact with the cunning and professional people of the plains. The plight of the poor and vulnerable Indian tribals has been surfacing from time to time for about hundred years or so. But after independence they have been considered a 'problem' for government and their more advanced fellow citizens. The administrators, anthropologists, sociologists, Christian missionaries and social workers have viewed this ‘problem’ from different perspectives. For the matter of convenience these views and policy approaches may be divided into three categories:

(i) Isolationism

(ii) Assimilationism

(iii) Integrationism.

The discussion that follows this categorization rotates round the three views. - Many of the so-called aboriginal people or tribals have been pronounced by all those who came into close contact with them as rather simple, truthful, honest, usually jovial, colourful and happy-go-lucky. They had their own peculiar social organization and some of them had retained it till their contact with the British. Even after the British contact, which rendered their contact with the Hindus more rapid and intensive, some of them retained it, especially those who have been governed through their old tribal organization. In the case of others, whether Hinduized or not, the organization itself has not completely disappeared but has been lacking in that vitality and vigour which are characteristic of true tribal life (Ghurye, 1963). Let us take a brief view of their social and economic organisation and then the resultant problems.

- Lots of these tribes have been practising a crude type of cultivation called shifting cultivation known by respective vernacular names. It required little labour, care and vital input. Under this scheme of cultivation trees and shrubs are felled with axe before the start of monsoon, fired and allowed to burn down into ashes. Now the desired seed is thrown and the nature is left to take care of the yield. To supplement their dietary requirement they collect all kinds of edible roots and fruits and hunt their favourable animals.

- Further, most of the tribal people are habituated to drink, formerly to their home brewed liquor of rice, mahua flower and other varieties and later to all kinds of distilled liquor. As a group, Jounsari, Bhil, Gond and numerous other tribes drink and even their children drink liberally. This is clue to their local environmental and ecological conditions. Liquor has also been a part of their ritual and religious practices.

- Contacts with Christian missionaries especially in Bihar and north eastern region played havoc with their spiritual world. The faith in their old gods was shaken and everything tribal was called blasphemous.

- Different tribes have different customs in regard to marriage and inheritance. The tribal customs were not properly understood and they were punished by the regular courts. If hurt the tribal sentiments.

- Tribal people have been illiterate. When various schemes were taken up for their educational upliftment, very little care was taken to impart primary education in their respective mother tongues even in case of informal education.

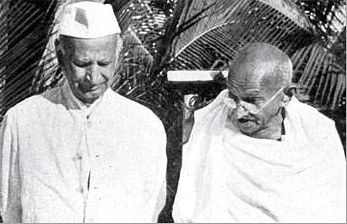

Thakkar Bapa, also known as “Tribal Gandhi” with Mahatma GandhiCommenting on the life and death struggle of many primitive tribes in India and elsewhere in consequence of adverse economic conditions, D.N. Majumdar enumerated eleven causes:

Thakkar Bapa, also known as “Tribal Gandhi” with Mahatma GandhiCommenting on the life and death struggle of many primitive tribes in India and elsewhere in consequence of adverse economic conditions, D.N. Majumdar enumerated eleven causes:- The excise laws have hit them hard,

- The displacement of tribal officers by those of the administration has disorganized tribal life in all aspects

- Tribal land used for shifting cultivation has been taken away from them

- Quarrying in the land owned is not allowed except with the payment of heavy licence fee

- Shifting cultivation is prohibited in most areas. The people, thus have been forced to take to the kind of agriculture unsuited to them or for which they do not know adequate offering and sacrifices which will "please the gods presiding over agriculture"

- Marriage by capture has been treated as an offence under the Indian Penal Code. It was generally resorted to in order to avoid payment of heavy bride price, and the substitute had worked smoothly. The recognition of this custom as offence punishable by law will seriously undermine social solidarity and lead to social disharmony. We know that late marriage is customary among the tribal people and there are large numbers of men and women in every tribe who cannot afford to marry under normal conditions.

- The fairs and weekly markets which have begun to attract tribal people are ruining them financially

- Education, which has been and is being imparted, has been more harmful than otherwise.

- The judicial officers have not been able to give them satisfactory justice.

- Missionary effort has resulted in creating in their minds a loathing for their own culture and a longing for things which they have no means to obtain.

- Contact has introduced diseases in tribal peoples for which they possess no efficient indigenous pharmacopoeia. Medical health rendered by the state is meagre.

- A.V. Thakkar, popularly known as "Thakkar Bapa", one of the most vociferous champions of tribal cause has analysed the situation in the straight manner of a social worker. According to him the problems of the aborigines may be analysed into

- poverty;

- illiteracy;

- health

- inaccessibility of the areas inhabited by tribals;

- defects in administration and

- lack of leadership.

- After viewing an anthropologist's and a social worker's reactions, let us take up Hutton's view, a defender of British policy of tribal affairs. According to Hutton, most cruel tribal customs were put down and warfare was stopped. Modern medicine was applied and infant mortality curtailed. The arts of reading and writing were introduced and easier intercourse and communication placed at their disposal through roads and post offices. However, the ills to which primitives were exposed to came from two slightly different aspects of British rule:

- Introduction of an administrative system which failed to take into account any special needs.

- Deliberate measures intended to ameliorate the condition of these tribes.

- Three major evils proceeded form these sources

- loss of land and supplanting of the tribal village headman by foreigners; particularly by the Hindus from the plains, whether cultivators, moneylenders, traders, or mere land grabbers; (b) loss of means of subsistence and (c) disintegration of tribal solidarity.

- After analysing the plight of the tribal people let us go back to the three major approaches to the tribal problems to assess the impact of these approaches.

- ISOLATION Protagonists of the first approach hold the view that all the alien links, responsible for the unregulated and unrestricted contacts with the -modern world and the resultant miserable condition of the tribes, should be snapped and the primitive people should be allowed and encouraged to flourish in their own primitive environment,

- This approach also includes what is now widely known as 'National Park Theory' credited to Verrier Elwin. He suggested that "the first necessity is the establishment of National Park, in which not only the Baiga but thousands of simple Gonds in their neighbourhood might take refuge. A fairly large area was to be marked out for this purpose. The areas should be under the direct control of a tribe's commissioner who should be an expert standing between them as was resorted to in the case of the Ho and Santhals, viz., through the leaders or headmen of the tribe. The usual other steps like licensing all non-aboriginals, were to be taken to safeguard the aboriginal from being exploited by unscrupulous adventurers. In short, the administration was to be so adjusted as to allow the tribesmen to live their lives with utmost possible happiness and freedom. No missionaries of any religion were to be allowed to breakup tribal life."

- This approach has been severely criticized on the ground that in the name of protecting the culture of the tribals, they cannot be kept aloof from the rest of India. They are not domestic cattle or zoo exhibits but equal citizens of free India. Thus they should be allowed to contribute towards the advancement of their country and enjoy the resultant fruits of development.

- ASSIMILATION

The second approach viz. assimilation has got considerable acceptance when lobbied by social workers. The protagonists of assimilation advance the view that tribes should be assimilated with their neighbouring nontribal cultures. - The policy of total assimilation has also not been in conformity with the trend of Indian history. Despite thousands of years of cultural contact and inter-cultural exchanges, Indian society could not become totally homogeneous. Some cultural characteristics did take shape that are truly national in character as the by product of historical development of Indian society. But it cannot be denied that Indian society has been formed with Santhal, Gond, Orya, Telegu, Kashmiri and numerous other cultural currents. Under such conditions the policy of total assimilation of tribal culture as the solution of their problems is unfair and futile. Even the thought of forced assimilation or putting it as fiat accompli smacks of cultural authoritarianism.

- Jawaharlal Nehru has been very outspoken in condemning the imposition of the Hindu way of living on tribal populations reared in another tradition. Due to his deep sympathy for the tribal people and keen appreciation of their problems, the approach of the state towards the tribal people is based on the theme of integration.

- INTEGRATION

The approach of integration of the tribal population with the rest of the Indian population on the basis of equality and mutual respect is propagated by the anthropologists. The principle of cultural autonomy has been an article of faith with the anthropologists. Integration should be differentiated from forced assimilation. We have got so many linguistic and religious groups who are being integrated to form one Indian nation without anybody being forced to give up their cultural identity and identify themselves with the majority community. Perhaps, there will be more meaningful and durable integration when every minority group feels secure; when, in this pluralistic society that India is, people can exist as Hindus, Muslims, Christians, and Sikhs etc. When one can exist here as Tamil, Oriya, Gujarati, Bengali, Punjabi etc. then why not a person can exist here with respect and dignity as a Santhal, a Gond, a Tharu, a Meena and a Yenadi? Integration can never be achieved under the shadow of threat and no plural society can afford to keep disgruntled, distressed, restless and frustrated minorities in its fold and still aspire for the harmonious development of the country. To ensure integration in this way the non-tribals need education as much as the tribals.