Working Class: Structure, Growth & Class Mobilization | Sociology Optional for UPSC (Notes) PDF Download

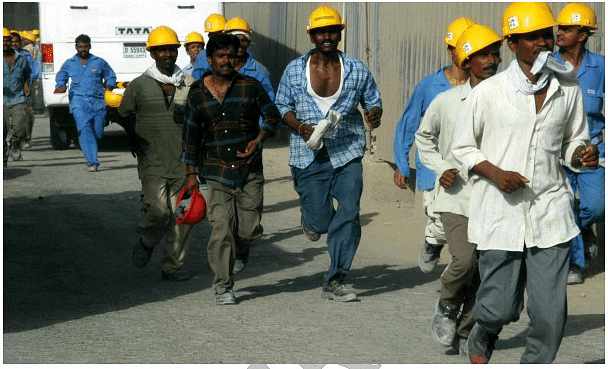

Working class in India reflects the heterogeneity of Indian society

Working class in India reflects the heterogeneity of Indian society

India's economy is characterized by a complex multi-structural system in which various precapitalist and capitalist production relations coexist. This leads to a differentiated working class structure, where numerous types of production, consumption, and surplus accumulation relationships create a variety of forms of the working class existence.

- The composition of the working class is further influenced by the structural features of Pan Indian society, as well as local conditions. Factors such as caste, tribe, ethnicity, and gender-based labor division, along with the associated patriarchy, all affect the working class composition.

- Despite these internal structural differences and diverse production relations, there exists a group of people referred to as the "working class." Analyzing the growth of the working class in India is essential, especially considering two facts. First, prior to the 19th century, there were a large number of working people in India who were not part of the working class. Second, the growth of capitalist production and industrialization in India was imposed by the colonial rulers.

Growth of Working Class in India

The emergence of the modern working class coincided with the development of the capitalist production mode, which introduced the factory-based industry. In other words, the growth of the working class and the factory system of production occurred concurrently. Without factory-based industries, there would be no working class, only working individuals.Traditional Indian Economy and Encounter with Colonialists

- In the 19th century, India had a working population but not a defined working class. The economy was characterized by small, ancient communities that relied on common land, a blend of agriculture and handicrafts, and a division of labor. However, the colonial rule and exploitation by British Imperialists disrupted the traditional system of production and self-sufficiency. The process began after the Battle of Plassey in 1757 and accelerated with the forced introduction of British capital, which shattered the old economic system and division of labor.

- The surplus generated through this system was taken by colonialists, who plundered and exported India's wealth to England. This was further exacerbated by the opening of free trade with India in 1813, which allowed not only the East India Company but also other British companies to trade freely, leading to the decline of the Indian textile industry and the impoverishment of artisans.

- The colonialists followed a trading policy that not only flooded the Indian market with British industrial products but also maintained a constant supply of Indian raw materials and agricultural products to England. This transformed India into an agrarian and raw material adjunct of capitalist Britain while simultaneously preserving feudal methods of exploitation.

- As a result, Indian craftsmen were forced out of their age-long professions, and the traditional integration of industrial and agricultural production was shattered. This led to the disintegration of the structure of Indian society and the loss of its unique economy.

(i) The formative Period

- The forced intrusion of British capital in India devastated the old economy but did not transplant it by forces of modem capital economy. So, traditional cottage industry and weavers famed for their skill through the centuries were robbed of their means of livelihood and were uprooted throughout India. This loss of the old world with no new gains led to extreme impoverishment of the people. The millions of ruined artisans and craftsmen, spinners, weavers, potters, smelters and smiths from the town and the village alike, had no alternative but to crowd into agriculture, leading to deadly pressure on the land.

- Subsequently, with the introduction of railways and sporadic growth of some industries, a section of these very people at the lowest rung of Indian society who had been plodding through immense sufferings and impoverishment in village life entered the modern industries as workers. The first generation of factory workers, it appears, came from this distressed and dispossessed section the village people. In the words of Buchanan. the factory working group surely comes from the hungry half of the agricultural population, indeed almost wholly from the hungriest quarter or eighth of it. The factory commission of 1890 reports that most of the factory workers in jute, cotton, bone and paper mills, sugar works, gun and shell factories belonged to the lower castes like Bagdi, Teli, Mochi, Kaibarta, Bairagi and Sankara.

- Migration of lower castes took place later (after 3040 years) due to two reasons. The factories (jute and cotton) faced labour shortage, hence wags were increased. Secondly, there was pressure from the British Govt. on the village community to allow untouchables to migrate outside the village.

- The view expressed earlier in this unit is Buchanan's and also Max Weber's who had written that industrialisation in India attracted the low castes and the dregs of society.

(ii) Emergence of working class

With the growth of modern factory industries, the factory workers gradually shaped themselves into a distinct category.

- The concentration of the working class in the cities near the industrial enterprises was an extremely important factor in the formation of the workers as a class. Similar conditions in factories and common living conditions made the workers feel that they had similar experiences and shared interests and react in similar fashion. In other words, the principal factors underlying the growth and formation of the working mass as a class in India in the latter half of the' 19th century, and at the beginning of 20th century, it bears similarities with the advanced countries of Europe.

- Side by side with these forms of protest there were also other forms of struggle characteristic of the working class. Typical working class actions such as strike against long hours of work, against wage cuts, against supervisors' extortion were increasing in number and the tendency to act collectively was also growing. As early as 1879/80 there was a threat of a strike in Charnadani Jute Mill against an attempt by the authorities to introduce a new system of single shift which was unpopular with workers. Presumably because of this strike threat the proposed system was ultimately abandoned. However, the process of class formation among workers in India was marked by fundamental differences as opposed to their European counterparts. It had far reaching consequences on the growth of the Indian working class. These differences were:

- Though in Europe also the artisans and craftsmen were dispossessed profession, they were not forced out of towns to crowd the village economy. They found employment in the 'large industries as soon as they were dispossessed of their old professions. In India, after the destruction of traditional handicraft and cottage industry, modern industry did not grow up in its place. The dispossessed artisans and craftsmen were compelled to depend on the village economy and earn livelihood as landless peasants and agricultural labourers.

- The gap between destruction of traditional cottage industry and its partial replacement by modern industries was about two to three generations. The dispossessed artisans and craftsmen lost their age old technical skill and when they entered the modern industries, they did so without any initial skills.

- When the workers, after long and close association with agricultural life, entered the modem industries and got transformed into modern workers, they did it in with the full inheritance of the legacy and various superstitions, habits and customs of agricultural life. There was no opportunity for these men to get out of casteism, racialism and religious superstition of Indian social life and harmful influence of medieval idea. They were born as an Indian working class deeply imbued with obscurantist ideas and backward trends. However, this feature they shared with some of their European counterparts, as well, such as British working class who too had suffered similar problems.

(iii) Consolidation of the working class

- The end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century saw organized national movements and the consolidation of the working class in India. The partition of Bengal in 1905 led to widespread public indignation, which provided favorable conditions for the Indian working class to advance in their economic struggles. The period up to World War I was marked by widespread industrialization, which led to the growth of trade unions and the expansion of the working class.

- World War I accelerated capitalist development in India, benefiting the Indian bourgeoisie through reduced competition and increased markets for goods. However, the working class faced tough times as prices soared, and living standards declined. The October socialist revolution and the end of World War I added new strength to India's anti-imperialist struggle, with the working class playing a crucial role. The All India Trade Union Congress (AITUC) was established as the first organization of the Indian working class during this time.

- The world economic crisis of 1931-36 had a devastating impact on India's economy, particularly in agriculture. The purchasing power of peasants fell to an all-time low, and workers across all industries faced mass retrenchment and wage cuts. Despite the challenges, the Indian working class continued to wage economic and political struggles against colonial exploitation. World War II further exacerbated the economic hardships faced by the working class, leading to a series of strikes and anti-war protests throughout the country.

- Following the defeat of fascism and the end of World War II, the Indian working class emerged as a class-conscious and uncompromising force against colonial rule. The struggle for national liberation and democratic advance swept the country, with workers fighting for better wages and working conditions. However, the government responded with repression, including police firings and other measures, leading to the loss of many workers' lives.

- India's independence brought about a change in the political climate and the objectives of the working class struggle. The power now lay with the capitalists and landlords, whose economic interests were directly opposed to those of the working class. The struggle shifted towards ending the rule of the capitalist class and establishing socialism. Although independence raised hopes for all sections of society, it was accompanied by a rise in prices and a decline in real wages. The working class continued to resist the hardships brought about by the ruling classes' pursuit of capitalism in the newly independent country.

Nature and Structure of the Working Class Today

The working class in India today can be characterized by its multistructural economy, primordial affiliations, and wage differences. Due to these factors, there are several forms of the working class, which can be divided into four categories based on wage. The first category consists of permanent employees in large factory sectors who receive a family wage, meaning their wage is sufficient to maintain not only themselves but also their families. These workers are predominantly employed in public sector enterprises and modern sectors such as petrochemicals, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and engineering.- The second category includes a large section of the working class that does not receive a family wage. Workers in this category are employed in older industries such as cotton and jute textiles, sugar, and paper. Permanent workers in tea plantations also fall into this category, as plantation owners refuse to accept the norm of family wage for individual workers. The third category consists of workers at the bottom of the wage scale, including contract laborers in industries like construction, brick making, and casual workers. Lastly, the fourth category consists of a reserve army of labor, who work in the informal sector in roles such as hawking and ragpicking, often for insufficient survival wages.

- Wage differentials among the working class in India also lead to variations in working conditions and job security. Better-paid laborers have greater job security, while those on the lower end of the wage scale experience more economic coercion and personal bondage, resulting in a lack of civil rights. Working conditions for low-paid workers are generally worse than for high-paid workers, with safety measures and protections varying significantly between the two groups. Women workers face additional challenges, as they are often barred from working in certain industries due to safety concerns but can still be employed on the same site as contract labor.

- Despite these divisions in the working class, there is limited mobility among workers in India. One might expect workers to progress from casual or contract labor to permanent employment, either within the same company or at another firm. However, studies have shown that the majority of regular employees began their careers as regular employees, rather than as casual laborers. Mobility is largely dependent on recruitment processes, which often rely on connections and social networks rather than merit-based hiring practices.

- The working class in India today is defined by its varied forms and wage differentials, with significant divisions based on industry, job security, and working conditions. Mobility among the working class is limited, with recruitment processes often favoring those with connections and social networks. The complex nature of the working class in India presents numerous challenges and highlights the need for continued efforts to improve conditions and opportunities for all workers.

Social Background of Indian Working Class

The Indian working class originates from a diverse range of social backgrounds, in which factors such as caste, ethnicity, religion, and language play crucial roles. Although the significance of these factors has diminished in recent years, they still persist.- The Ahmadabad study (1973) highlights the importance of these social connections in securing employment. The study found that in cases where jobs were obtained through introductions from other workers, 35% were blood relatives, 44% belonged to the same caste, and 12% were from the same native place. Friends helped in 7% of the cases. Other studies have also emphasized the role of kinship ties in gaining employment (Gore 1970). These kinship ties not only help in securing jobs but also influence placement within the wage scale.

- Several studies, including those from Pune, Kota, Bombay, Ahmadabad, and Bangalore, have found that a majority of workers (61%) belonged to the upper caste Hindu community (Sharma 1970). This dominance of upper caste workers was also observed in a study conducted in Kerala, which revealed that upper castes were more likely to hold higher-income jobs, while Dalits and Adivasis were more likely to have low-wage jobs. Middle castes were concentrated in the lower-middle to bottom range of the wage scale. The study also found that the representation of backward castes, scheduled castes, and tribes in public sector employment was not proportionate to their population. Furthermore, a caste-based division of labor was observed in class III and IV government and public sector jobs, with roles such as sweepers reserved for Dalits and Adivasis.

- In industries such as coal mines and steel plants, the physically demanding work is primarily carried out by Dalits and Adivasis. Deshpande (1979) attributes this to the pre-labor market characteristics of education and landholding. Those with more education and landholdings are more likely to secure higher-wage jobs. However, even when upper and lower caste individuals have comparable levels of landholding and education, upper caste workers are more likely to secure higher-paying positions due to the persistence of caste-based networks in recruitment.

- Caste also plays a role in maintaining a supply of cheap labor for various jobs, as the depressed socioeconomic conditions of Adivasis and Dalits ensure the availability of laborers who can be employed at subsistence-level wages (Nathan 1987). Therefore, caste not only contributes to keeping lower sections of society within the lower strata of the working class but also provides upper caste individuals with privileges in the labor market. Furthermore, caste continues to be a crucial factor in shaping social relationships and determining the supply of labor for the capitalist mode of production.

Conclusion

The growth of the working class in India has been shaped by a complex interplay of historical, economic, and social factors. The colonial rule's disruption of traditional production systems and the subsequent development of modern industries led to the emergence of a diverse working class, characterized by its multi-structural economy, varied forms, and wage differentials. The persistence of caste, tribe, ethnicity, and gender-based divisions further complicates the working class composition, limiting mobility and often perpetuating inequalities. Despite these challenges, the Indian working class continues to play a vital role in the country's economic development and remains a key focus for efforts to improve living and working conditions for all.Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) of Working Class: Structure, Growth & Class Mobilization

How has the colonial rule impacted the growth of the working class in India?

Colonial rule and exploitation by the British disrupted India's traditional system of production and self-sufficiency, leading to the decline of the Indian textile industry and impoverishment of artisans. The forced introduction of British capital shattered the old economic system and division of labor, transforming India into an agrarian and raw material adjunct of capitalist Britain.

What are the four categories of the working class in India based on wage?

The four categories of the working class in India based on wage are: (1) permanent employees in large factory sectors who receive a family wage; (2) workers who do not receive a family wage, employed in older industries like cotton and jute textiles, sugar, and paper; (3) workers at the bottom of the wage scale, including contract laborers in industries like construction, brick making, and casual workers; and (4) a reserve army of labor working in the informal sector, often for insufficient survival wages.

What factors contribute to the limited mobility among workers in India?

Limited mobility among workers in India is largely dependent on recruitment processes, which often rely on connections and social networks rather than merit-based hiring practices. Furthermore, caste-based networks persist in the labor market, providing upper caste individuals with privileges and keeping lower sections of society within the lower strata of the working class.

How does caste play a role in the working class in India?

Caste plays a significant role in the working class in India by influencing job placements within the wage scale, as well as maintaining a supply of cheap labor for various jobs. Upper caste workers are more likely to secure higher-income jobs, while Dalits and Adivasis are more likely to have low-wage jobs. Caste-based networks also persist in recruitment, providing upper caste individuals with privileges in the labor market.

What challenges do women workers face in the Indian working class?

Women workers face additional challenges in the Indian working class, as they are often barred from working in certain industries due to safety concerns but can still be employed on the same site as contract labor. This can lead to limited opportunities and wage discrepancies compared to their male counterparts.

|

122 videos|252 docs

|

|

Explore Courses for UPSC exam

|

|