Reading for IELTS Academic Practice Test- 7 | Reading Practice Tests for IELTS Academic PDF Download

Section- 1

The Dinosaurs Footprints and Extinction

(A) EVERYBODY knows that the dinosaurs were killed by an asteroid. Something big hit the earth 65 million years ago and, when the dust had fallen, so had the great reptiles. There is thus a nice, if ironic, symmetry in the idea that a similar impact brought about the dinosaurs' rise. That is the thesis proposed by Paul Olsen, of Columbia University, and his colleagues in this week's Science.

(B) Dinosaurs first appear in the fossil record 230m years ago, dining the Triassic period. But they were mostly small, and they shared the earth with lots of other sorts of reptile. It was in the subsequent Jurassic, which began 202million years ago, that they overran the planet and turned into the monsters depicted in the book and movie “Jurassic Park”. (Actually, though, the dinosaurs that appeared on screen were from the still more recent Cretaceous period.) Dr Olsen and his colleagues are not the first to suggest that the dinosaurs inherited the earth as the result of an asteroid strike. But they are the first to show that the takeover did, indeed, happen in a geological eyeblink.

(C) Dinosaur skeletons are rare. Dinosaur footprints are, however, surprisingly abundant. And the sizes of the prints are as good an indication of the sizes of the beasts as are the skeletons themselves. Dr. Olsen and his colleagues therefore concentrated on prints, not bones.

(D) The prints in question were made in eastern North America, a part of the world then full of rift valleys similar to those in East Africa today. Like the modem African rift valleys, the Triassic /Jurassic American ones contained lakes, and these lakes grew and shrank at regular intervals because of climatic changes caused by periodic shifts in the earth's orbit. (A similar phenomenon

is responsible for modem ice ages.) That regularity, combined with reversals in the earth's magnetic field, which are detectable in the tiny fields of certain magnetic minerals, means that rocks from this place and period can be dated to within a few thousand years. As a bonus, squish lake-edge sediments are just the things for recording the tracks of passing animals. By dividing the labour between themselves, the ten authors of the paper were able to study such tracks at 80 sites.

(E) The researchers looked at 18 so-called ichnotaxa. These are recognisable types of footprint that cannot be matched precisely with the species of animal that left them. But they can be matched with a general sort of animal, and thus act as an indicator of the fate of that group, even when there are no bones to tell the story. Five of the ichnotaxa disappear before the end of the Triassic, and four march confidently across the boundary into the Jurassic. Six, however, vanish at the boundary, or only just splutter across it; and three appear from nowhere, almost as soon as the Jurassic begins.

(F) That boundary itself is suggestive. The first geological indication of the impact that killed the dinosaurs was an unusually high level of iridium in rocks at the end of the Cretaceous, when the beasts disappear from the fossil record. Iridium is normally rare at the earth's surface, but it is more abundant in meteorites. When people began to believe the impact theory, they started looking for other Cretaceous-end anomalies. One that turned up was a surprising abundance of fern spores in rocks just above the boundary layer—a phenomenon known as a “fern spike”

(G) That matched the theory nicely. Many modem ferns are opportunists. They cannot compete against plants with leaves, but if a piece of land is cleared by, say, a volcanic emption, they are often the first things to set up shop there. An asteroid strike would have scoured much of the earth of its vegetable cover, and provided a paradise for ferns. A fem spike in the rocks is thus a good indication that southing terrible has happened.

(H) Both an iridium anomaly and a fem spike appear in rocks at the end of the Triassic, too. That accounts for the disappearing ichnotaxa: the creatures that made them did not survive the holocaust. The surprise is how rapidly the new ichnotaxa appear.

(I) Dr Olsen and his colleagues suggest that the explanation for this rapid increase in size may be a phenomenon called ecological release. This is seen today when reptiles (which, in modem times, tend to be small creatures) reach islands where they face no competitors. The most spectacular example is on the Indonesian island of Komodo, where local lizards have grown so large that they are often referred to as dragons. The dinosaurs, in other words, could flourish only when the competition had been knocked out.

(J) That leaves the question of where the impact happened. No large hole in the earth's crust seems to be 202m years old. It may, of course, have been overlooked. Old craters are eroded and buried, and not always easy to find. Alternatively, it may have vanished. Although continental crust is more or less permanent, the ocean floor is constantly recycled by the tectonic processes that bring about continental drift. There is no ocean floor left that is more than 200m years old, so a crater that formed in the ocean would have been swallowed up by now.

(K) There is a third possibility, however. This is that the crater is known, but has been misdated. The Manicouagan “structure”, a crater in Quebec, is thought to be 214m years old. It is huge—some 100km across—and seems to be the largest of between three and five craters that formed within a few hours of each other as the lumps of a disintegrated comet hit the earth one by one.

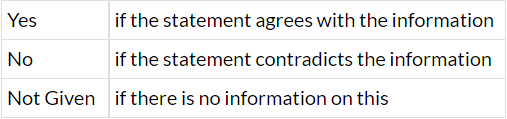

Questions 1-6: Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 1? In boxes 1-6 on your answer sheet, write

Q.1. Dr Paul Olsen and his colleagues believe that asteroid knock may also lead to dinosaurs’ boom.

Q.2. Books and movie like Jurassic Park often exaggerate the size of the dinosaurs.

Q.3. Dinosaur footprints are more adequate than dinosaur skeletons.

Q.4. The prints were chosen by Dr Olsen to study because they are more detectable than earth magnetic field to track a date of geological precise within thousands years.

Q.5. Ichnotaxa showed that footprints of dinosaurs offer exact information of the trace left by an individual species.

Q.6. We can find more Iridium in the earth’s surface than in meteorites.

Questions 7-13:Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage, using no more than two words from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 7-13 on your answer sheet.

Dr Olsen and his colleagues applied a phenomenon named ____ 7 ____ to explain the large size of the Eubrontes, which is a similar case to that nowadays reptiles invade a place where there are no ____ 8 ____; for example, on an island called Komodo, indigenous huge lizards grow so big that people even regarding them as ____ 9____. However, there were no old impact trace being found? The answer may be that we have ____ 10 ____ the evidence. Old craters are difficult to spot or it probably ____11 ____ due to the effect of the earth moving. Even a crater formed in Ocean had been ____ 12 ____ under the impact of crust movement. Beside the third hypothesis is that the potential evidences — some craters may be ____ 13 ____.

Section- 2

WHAT COOKBOOKS REALLY TEACH US

(A) Shelves bend under their weight of cookery books. Even a medium-sized bookshop contains many more recipes than one person could hope to cook m a lifetime. Although the recipes in one book are often similar to those in another, their presentation varies wildly, from an array of vegetarian cookbooks to instructions on cooking the food that historical figures might have eaten. The reason for this abundance is that cookbooks promise to bring about a land of domestic transformation for the user. The daily routine can be put to one side and they liberate the user, if only temporarily. To follow their instructions is to turn a task which has to be performed every day into an engaging, romantic process. Cookbooks also provide an opportunity to delve into distant cultures without having to turn up at an airport to get there.

(B) The first Western cookbook appeared just over 1,600 years ago. De re coquinara (it means concerning cookery1) is attributed to a Roman gourmet named Apicius. It is probably a complilation of Roman and Greek recipes, some or all of them drawn from manuscripts that were later lost. The editor was sloppy, allowing several duplicated recipes to sneak in. Yet Apicius’s book set die tone of cookery advice in Europe for more than a thousand years. As a cookbook it is unsatisfactory with very basic instructions. Joseph Vehling, a chef who translated Apicius in the 1930s, suggested the author had beat obscure on purpose, in case his secrets leaked out.

(C) But a more likely reason is that Apicius’s recipes were written by and for professional cooks, who could follow their shorthand. This situation continued for hundreds of years. There was no order to cookbooks: a cake recipe might be followed by a mutton one. But then, they were not written for careful study. Before the 19th century few educated people cooked for themselves.

(D) The wealthiest employed literate chefs; others presumably read recipes to their servants. Such cooks would have been capable of creating dishes from the vaguest of instructions. The invention of printing might have been expected to lead to greater clarity but at first the reverse was true. As words acquired commercial value, plagiarism exploded Recipes were distorted through reproduction A recipe for boiled capon in The Good Huswives Jewell, printed in 1596t advised the cook to add three or four dates. By 1653, when the recipe was given by a different author in A Book of Fruits & Flowers, the cook was told to set the dish aside for three or four days.

(E) The dominant theme in 16th and 17th century cookbooks was order. Books combined recipes and household advice, on the assumption that a well-made dish, a well-ordered larder and well-disciplined children were equally important. Cookbooks thus became a symbol of dependability in chaotic times. They hardly seem to have been affected by the English civil war or the revolutions in America and France.

(F) In the 1850s Isabella Beeton published The Book of Household Management. Like earlier cookery writers she plagiarised freely, lifting not just recipes but philosophical observations from other hooks. If Beetons recipes wore not wholly new, though, the way in which she presented them certainly was. She explains when the chief ingredients are most likely to be in season, how long the dish will take to prepare and even how much it is likely to cost. Beetons recipes were well suited to her times. Two centuries earlier, an understanding of rural ways had been so widespread that one writer could advise cooks to heat water until it was a little hotter than milk comes from a cow. By the 1850b Britain was industrialising. The growing urban midrib class needed details, and Beeton provided them in full.

(G) In France, cookbooks were last becoming even more systematic. Compared with Britain, France had produced few books written for the ordinary householder by the end of the 19th century. The most celebrated French cookbooks were written by superstar chefs who had a clear sense of codifying a unified approach to sophisticated French cooking. The 5,000 recipes in Auguste Escoffiers Le Guide Culinaire (The Culinary Guide), published in 1902, might as well have been written in stone, given the book's reputation among French chefs, many of whom still consider it the definitive reference book.

(H) What Escoffier did for French cooking, Fannie Farmer did for American home cooking. She not only synthesised American cuisine; she elevated it to the status of science. ‘Progress in civilisation has been accompanied by progress in cookery,’ she breezily announced in The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book, before launching into a collection of recipes that sometimes resembles a book of chemistry experiments. She was occasionally over-fussy. She explained that currants should be picked between June 28th and July 3rd, but not when it is raining. But in the main her book is reassuringly authoritative. Its recipes are short, with no unnecessary chat and no unnecessary spices.

(I) In 1950 Mediterranean Food by Elizabeth David launched a revolution in cooking advice in Britain. In some ways Mediterranean Food recalled even older cookbooks but the smells and noises that filled David’s books were not mere decoration for her recipes. They were the point of her books. When she began to write, many ingredients were not widely available or affordable. She understood this, acknowledging in a later edition of one of her books that even if people could not very often make the dishes here described, it was stimulating to think about them.’ David’s books were not so much cooking manuals as guides to the kind of food people might well wish to eat.

Questions 14-16: Complete the summary below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS firm the passage for each answer. Write your answers inboxes 14-16 on your answer sheet.

Why are there so many cookery books?

There are a great number more cookery books published than is really necessary and it is their 14 ____ which makes them differ from each other. There are such large numbers because they offer people an escape from their 15 ____ and some give the user the chance to inform themselves about other 16 ____

Questions 17-21: Reading Passage has nine paragraphs, A-I Which paragraph contains the following information? Write the correct letter, A-I in boxes 17-21 on your answer sheet.

NB: YOU MAY USE ANY LETTER MORE THAN ONCE.

Q17: cookery books providing a sense of stability during periods of unrest

Q18: details in recipes being altered as they were passed on

Q19: knowledge which was in danger of disappearing

Q20: the negative effect on cookery books of a new development

Q21: a period when there was no need for cookery books to be precise

Questions 22-26: Look at the following statements (Questions 22-26) and list of books (A-E) below. Match each statement with the correct book. Write the correct letter, A-E, m boxes 22-26 on your answer sheet

Q22: Its recipes were easy to follow despite the writer’s attention to detail.

Q23: Its writer may have deliberately avoided pawing on details.

Q24: It appealed to ambitious ideas people have about cooking.

Q25: Its writer used ideas from other books but added additional related information.

Q26: It put into print ideas which are still respected today.

List of cookery books

(A) De re coquinara

(B) The Book of Household Management

(C) Le Guide Culinaire

(D) The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book

(E) Mediterranean Food

Section- 3

Learning lessons from the past

(A) Many past societies collapsed or vanished, leaving behind monumental ruins such as those that the poet Shelley imagined in his sonnet, Ozymandias. By collapse, I mean a drastic decrease in human population size and/or political/economic/social complexity, over a considerable area, for an extended time. By those standards, most people would consider the following past societies to have been famous victims of full-fledged collapses rather than of just minor declines: the Anasazi and Cahokia within the boundaries of the modem US, the Maya cities in Central America, Moche and Tiwanaku societies in South America, Norse Greenland, Mycenean Greece and Minoan Crete in Europe, Great Zimbabwe in Africa, Angkor Wat and the Harappan Indus Valley cities in Asia, and Easter Island in the Pacific Ocean.

(B) The monumental ruins left behind by those past societies hold a fascination for all of us. We marvel at them when as children we first learn of them through pictures. When we grow up, many of us plan vacations in order to experience them at first hand. We feel drawn to their often spectacular and haunting beauty, and also to the mysteries that they pose. The scales of the ruins testify to the former wealth and power of their builders. Yet these builders vanished, abandoning the great structures that they had created at such effort. How could a society that was once so mighty end up collapsing?

(C) It has long been suspected that many of those mysterious abandonments were at least partly triggered by ecological problems: people inadvertently destroying the environmental resources on which their societies depended. This suspicion of unintended ecological suicide (ecocide) has been confirmed by discoveries made in recent decades by archaeologists, climatologists, historians, palaeontologists, and palynologists (pollen scientists). The processes through which past societies have undermined themselves by damaging their environments fall into eight categories, whose relative importance differs from case to case: deforestation and habitat destruction, soil problems, water management problems, overhunting, overfishing, effects of introduced species on native species, human population growth, and increased impact of people.

(D) Those past collapses tended to follow somewhat similar courses constituting variations on a theme. Writers find in tempting to draw analogies between the course of human societies and the course of individual human lives – to talk of a society’s birth, growth, peak, old age and eventual death. But that metaphor proves erroneous for many past societies: they declined rapidly after reaching peak numbers and power, and those rapid declines must have come as a surprise and shock to their citizens. Obviously, too, this trajectory is not one that all past societies followed unvaryingly to completion: different societies collapsed to different degrees and in somewhat different ways, while many societies did not collapse at all.

(E) Today many people feel that environmental problems overshadow all the other threats to global civilisation. These environmental problems include the same eight that undermined past societies, plus four new ones: human-caused climate change, the build-up of toxic chemicals in the environment, energy shortages, and full human utilisation of the Earth’s photosynthetic capacity. But the seriousness of these current environmental problems is vigorously debated. Are the risks greatly exaggerated, or conversely are they underestimated? Will modem technology solve our problems, or is it creating new problems faster than it solves old ones? When we deplete one resource (eg wood, oil, or ocean fish), can we count on being able to substitute some new resource (eg plastics, wind and solar energy, or farmed fish)? Isn’t the rate of human population growth declining, such that we’re already on course for the world’s population to level off at home manageable number of people?

(F) Questions like this illustrate why those famous collapses of past civilisations have taken on more meaning than just that of a romantic mystery. Perhaps there are some practical lessons that we could learn from all those past collapses. But there are also differences between the modem world and its problems, and those past societies and their problems. We shouldn’t be so naive as to think that the study of the past will yield simple solutions, directly transferable to our societies today. We differ from past societies in some respects that put us at lower risk than them; some of those respects often mentioned include our powerful technology (i.e. its beneficial effects), globalisation, modem medicine, and greater knowledge of past societies and of distant modem societies. We also differ from past societies in some respects that put us at greater risk than them: again, our potent technology (ie its unintended destructive effects), globalisation (such that now a problem in one part of the world affects all the rest), the dependence of millions of us on modern medicine for our survival, and our much larger human population. Perhaps we can still learn from the past, but only if we think carefully about its lessons.

Questions 27-29:

Choose the correct letter A, B, C or D.

Q27: When the writer describes the impact of monumental ruins today, he emphasizes

(A) the income they generate from tourism.

(B) the area of land they occupy.

(C) their archaeological value.

(D) their romantic appeal.

Q28: Recent findings concerning vanished civilisations

(A) have overturned long-held beliefs.

(B) caused controversy amongst scientists.

(C) come from a variety of disciplines.

(D) identified one main cause of environmental damage.

Q29: What does the writer say about ways in which former societies collapsed?

(A) The pace of decline was usually similar.

(B) The likelihood of collapse would have been foreseeable.

(C) Deterioration invariably led to total collapse.

(D) Individual citizens could sometimes influence the course of events.

Questions 30-34:

Do the following statements agree with the views of the writer in Reading Passage?

Write

YES – if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

NO – if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

NOT GIVEN – if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

Q30: It is widely believed that environmental problems represent the main danger faced by the modern world.

Q31: The accumulation of poisonous substances is a relatively modern problem.

Q32: There is general agreement that the threats posed by environmental problems are very serious.

Q33: Some past societies resembled present-day societies more closely than others.

Q34: We should be careful when drawing comparisons between past and present.

Questions 35-39:

Complete each sentence with the correct ending, A-F, below.

Write the correct letter, A-F

Q35: Evidence of the greatness of some former civilisations

Q36: The parallel between an individual’s life and the life of a society

Q37: The number of environmental problems that societies face

Q38: The power of technology

Q39: A consideration of historical events and trends

(a) is not necessarily valid.

(b) provides grounds for an optimistic outlook.

(c) exists in the form of physical structures.

(d) is potentially both positive and negative.

(e) will not provide direct solutions for present problems.

(f) is greater now than in the past.

Question 40:

Choose the correct letter A, B, D or D

Q40: What is the main argument of Reading Passage 3?

(A) There are differences as well as similarities between past and present societies.

(B) More should be done to preserve the physical remains of earlies civilisations.

(C) Some historical accounts of great civilisations are inaccurate.

(D) Modern societies are dependent on each other for their continuing survival.

FAQs on Reading for IELTS Academic Practice Test- 7 - Reading Practice Tests for IELTS Academic

| 1. What is the format of the IELTS exam? |  |

| 2. How is the IELTS exam scored? |  |

| 3. Can I use a pen instead of a pencil for the Writing section of the IELTS exam? |  |

| 4. What is the difference between the Academic and General Training versions of the IELTS exam? |  |

| 5. Can I bring a dictionary into the IELTS exam? |  |