Reading for IELTS Academic Practice Test- 16 | Reading Practice Tests for IELTS Academic PDF Download

Section - 1

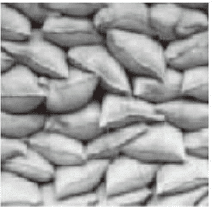

(A) LAST winter’s floods on the rivers of central Europe were among the worst since the Middle Ages, and as winter storms return, the spectre of floods is returning too. Just weeks ago, the river Rhone in south-east France burst its banks, driving 15,000 people from their homes, and worse could be on the way. Traditionally, river engineers have gone for Plan A: get rid of the water fast, draining it off the land and down to the sea in tall-sided rivers re-engineered as high-performance drains. But however big they dig city drains, however wide and straight they make the rivers, and however high they build the banks, the floods keep coming back to taunt them, from the Mississippi to the Danube. And when the floods come, they seem to be worse than ever.

(A) LAST winter’s floods on the rivers of central Europe were among the worst since the Middle Ages, and as winter storms return, the spectre of floods is returning too. Just weeks ago, the river Rhone in south-east France burst its banks, driving 15,000 people from their homes, and worse could be on the way. Traditionally, river engineers have gone for Plan A: get rid of the water fast, draining it off the land and down to the sea in tall-sided rivers re-engineered as high-performance drains. But however big they dig city drains, however wide and straight they make the rivers, and however high they build the banks, the floods keep coming back to taunt them, from the Mississippi to the Danube. And when the floods come, they seem to be worse than ever.

(B) No wonder engineers are turning to Plan B: sap the water’s destructive strength by dispersing it into fields, forgotten lakes, flood plains and aquifers. Back in the days when rivers took a more tortuous path to the sea, flood waters lost impetus and volume while meandering across flood plains and idling through wetlands and inland deltas. But today the water tends to have an unimpeded journey to the sea. And this means that when it rams in the uplands, the water comes down all at once. Worse, whenever we close off more flood plain, the river’s flow farther downstream becomes more violent and uncontrollable. Dykes are only as good as their weakest link - and the water will unerringly find it.

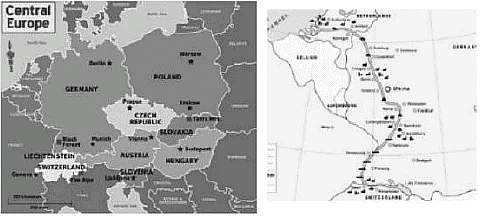

(C) Today, the river has lost 7 per cent of its original length and runs up to a th u d faster. When it rains hard in the Alps, the peak flows from several tributaries coincide in the main river, where once they arrived separately. And with four-fifths of the lower Rhine’s flood plain barricaded off, the waters rise ever higher. The result is more frequent flooding that does ever-greater damage to the homes, offices and roads that sit on the flood plain. Much the same has happened in the US on the mighty Mississippi, which drains the world’s second largest river catchment into the Gulf of Mexico.

(D) The European Union is trying to improve rain forecasts and more accurately model how intense rains swell rivers. That may help cities prepare, but it won’t stop the floods. To do that, say hydrologists, you need a new approach to engineering not just Agency - country £1 billion - puts it like this: "The focus is now on working with the forces of nature. Towering concrete walls are out, and new wetlands are in." To help keep London’s upstream and reflooding 10 square k outside Oxford. Nearer to London it has spent £100 million creating new wetlands and a relief channel across 16 kilometres.

(E) The same is taking place on a much grander scale in Austria, in one of Europe’s largest river restorations to date. Engineers are regenerating flood plains along 60 kilometres of the river Drava as it exits the Alps. They are also widening the river bed and channelling it back into abandoned meanders, oxbow lakes and backwaters overhung with willows. The engineers calculate that the restored flood plain can now store up to 10 million cubic metres of flood waters and slow storm surges coming out of the Alps by more than an hour, protecting towns as far downstream as Slovenia and Croatia.

(F) "Rivers have to be allowed to take more space. They have to be turned from flood-chutes into flood-foilers," says Nienhuis. And the Dutch, for whom preventing floods is a matter of survival, have gone furthest. A nation built largely on drained marshes and seabed had the fright of its life in 1993 when the Rhine almost overwhelmed it. The same happened again in 1995, when a quarter of a million people were evacuated from the Netherlands. But a new breed of "soft engineers" wants our cities to become porous, and Berlin is theft governed by tough new rules to prevent its drains becoming overloaded after heavy rains. Harald Kraft, an architect working in the city, says: "We now see rainwater as giant Potsdamer Platz, a huge new commercial redevelopment by Daimler Chrysler in the heart of the city.

(G) Los Angeles has spent billions of dollars digging huge drains and concreting river beds to carry away the water from occasional intense storms. "In LA we receive half the water we need in rainfall, and we throw it away. Then we spend hundreds of millions to import water," says Andy Lipkis, an LA environmentalist who kick-started the idea of the porous city by showing it could work on one house. Lipkis, along with citizens groups like Friends of the Los Angeles River and Unpaved LA, want to beat the urban flood hazard and fill the taps by holding onto the city’s flood water. And it’s not just a pipe dream. The authorities this year launched a $100 million scheme to road-test the porous city in one flood-hit community in Sun Valley. The plan is to catch the rain that falls on thousands of driveways, parking lots and rooftops in the valley. Trees will soak up water from parking lots. Homes and public buildings will capture roof water to irrigate gardens and parks. And road drains will empty into old gravel pits and other leaky places that should recharge the city’s underground water reserves. Result: less flooding and more water for the city. Plan B says every city should be porous, every river should have room to flood naturally and every coastline should be left to build its own defences. It sounds expensive and utopian, until you realise how much we spend trying to drain cities and protect our watery margins - and how bad we are at it.

Questions 1-6: The reading Passage has seven paragraphs A-G. Which paragraph contains the following information? Write the correct letter A-G, in boxes 1-6 on your answer sheet.

Q.1. A new approach carried out in the UK

Q.2. Reasons why twisty path and dykes failed

Q.3. Illustration of an alternative Plan in LA which seems much unrealistic

Q.4. Traditional way of tackling flood

Q.5. Effort made in Netherlands and Germany

Q.6. One project on a river benefits three nations

Questions 7-11: Summary

Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage, using no more than two words from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 7-11 on your answer sheet.

Flood makes river shorter than it used to be, which means faster speed and more damage to constructions on flood plain. Not only European river poses such threat but the same things happens to the powerful ____7____in the US. In Europe, one innovative approach carried out by UK’s Environment Agency, for example a wetland instead of concrete walls is generated not far from the city of ____8____to protect it from flooding. In 1995, Rhine flooded again and thousands of people left the country of ____9____. A league of engineers suggested that cities should be porous, ____10____set an good example for others. Another city devastated by heavy storms casually is ____11____, though its government pours billions of dollars each year in order to solve the problem.

Questions 12-13: Choose TWO correct letter, write your answers in boxes 12-13 on your answer sheet

What TWO benefits will the new approach in the UK and Austria bring to US according to this passage?

(a) We can prepare before flood comes

(b) It may stop the flood involving the whole area

(c) Decrease strong rainfalls around Alps simply by engineering constructions

(d) Reserve water to protect downstream towns

(e) Store tons of water in downstream area

Section - 2

Tulips are spring-blooming perennials that grow from bulbs. Depending on the species, tulip plants can grow as short as 4 inches (10 cm) or as high as 28 inches (71 cm). The tulip's large flowers usually bloom on scapes or sub-scapose stems that lack bracts. Most tulips produce only one flower per stem, but a few species bear multiple flowers on their scapes (e.g. Tulipa turkestanica). The showy, generally cup or star-shaped tulip flower has three petals and three sepals, which are often termed tepals because they are nearly identical. These six tepals are often marked on the interior surface near the bases with darker colorings. Tulip flowers come in a wide variety of colors, except pure blue (several tulips with "blue" in the name have a faint violet hue)

(A) Long before anyone ever heard of Qualcomm, CMGI, Cisco Systems, or the other high-tech stocks that have soared during the current bull market, there was Semper Augustus. Both more prosaic and more sublime than any stock or bond, it was a tulip of extraordinary beauty, its midnight-blue petals topped by a band of pure white and accented with crimson flares. To denizens of 17th century Holland, little was as desirable.

(B) Around 1624, the Amsterdam man who owned the only dozen specimens was offered 3,000 guilders for one bulb. While there’s no accurate way to render that in today’s greenbacks, the sum was roughly equal to the annual income of a wealthy merchant. (A few years later, Rembrandt received about half that amount for painting The Night Watch.) Yet the bulb’s owner, whose name is now lost to history, nixed the offer.

(C) Who was crazier, the tulip lover who refused to sell for a small fortune or the one who was willing to splurge. That’s a question that springs to mind after reading Tulip mania: The Story of the World’s Most Coveted Flower and the Extraordinary Passions It Aroused by British journalist Mike Dash. In recent years, as investors have intentionally forgotten everything they learned in Investing 101 in order to load up on unproved, unprofitable dotcom issues, tulip mania has been invoked frequently. In this concise, artfully written account, Dash tells the real history behind the buzzword and in doing so, offers a cautionary tale for our times.

(D) The Dutch were not the first to go gaga over the tulip. Long before the first tulip bloomed in Europe-in Bavaria, it turns out, in 1559-the flower had enchanted the Persians and bewitched the rulers of the Ottoman Empire. It was in Holland, however, that the passion for tulips found its most fertile ground, for reasons that had little to do with horticulture.

(E) Holland in the early 17th century was embarking on its Golden Age. Resources that had just a few years earlier gone toward fighting for independence from Spain now flowed into commerce. Amsterdam merchants were at the center of the lucrative East Indies trade, where a single voyage could yield profits of 400%. They displayed their success by erecting grand estates surrounded by flower gardens. The Dutch population seemed tom by two contradictory impulses: a horror of living beyond one’s means and the love of a long shot.

(F) Enter the tulip. "It is impossible to comprehend the tulip mania without understanding just how different tulips were from every other flower known to horticulturists in the 17th century," says Dash. "The colors they exhibited were more intense and more concentrated than those of ordinary plants." Despite the outlandish prices commanded by rare bulbs, ordinary tulips were sold by the pound. Around 1630, however, a new type of tulip fancier appeared, lured by tales of fat profits. These "florists," or professional tulip traders, sought out flower lovers and speculators alike. But if the supply of tulip buyers grew quickly, the supply of bulbs did not. The tulip was a conspirator in the supply squeeze: It takes seven years to grow one from seed. And while bulbs can produce two or three clones, or "offsets," annually, the mother bulb only lasts a few years.

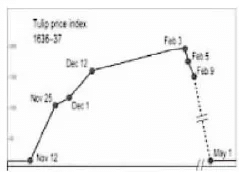

(G) Bulb prices rose steadily throughout the 1630s, as ever more speculators into the market. Weavers and farmers mortgaged whatever they could to raise cash to begin trading. In 1633, a farmhouse in Hoorn changed hands for three rare bulbs. By 1636 any tulip-even bulbs recently considered garbage-could be sold off, often for hundreds of guilders. A futures market for bulbs existed, and tulip traders could be found conducting their business in hundreds of Dutch taverns. Tulip mania reached its peak during the winter of 1636-37, when some bulbs were changing hands ten times in a day. The zenith came early that winter, at an auction to benefit seven orphans whose only asset was 70 fine tulips left by then father. One, a rare Violetten Admirael van Enkhuizen bulb that was about to split in two, sold for 5,200 guilders, the all-time record. All told, the flowers brought in nearly 53,000 guilders.

(H) Soon after, the tulip market crashed utterly, spectacularly. It began in Haarlem, at a routine bulb auction when, for the first time, the greater fool refused to show up and pay. Within days, the panic had spread across the country. Despite the efforts of traders to prop up demand, the market for tulips evaporated. Flowers that had commanded 5,000 guilders a few weeks before now fetched one-hundredth that amount. Tulip mania is not without flaws. Dash dwells too long on the tulip’s migration from Asia to Holland. But he does a service with this illuminating, accessible account of incredible financial folly.

(I) Tulip mania differed in one crucial aspect from the dot-com craze that grips our attention today: Even at its height, the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, well-established in 1630, wouldn’t touch tulips. "The speculation in tulip bulbs always existed at the margins of Dutch economic life," Dash writes. After the market crashed, a compromise was brokered that let most traders settle then debts for a fraction of then liability. The overall fallout on the Dutch economy was negligible. Will we say the same when Wall Street’s current obsession finally runs its course?

Questions 14-18: The reading Passage has seven paragraphs A-I. Which paragraph contains the following information ? Write the correct letter A-I, in boxes 14-18 on your answer sheet.

Q.14. Difference between bubble burst impacts by tulip and by high-tech shares

Q.15. Spread of tulip before 17th century

Q.16. Indication of money offered for rare bulb in 17th century

Q.17. Tulip was treated as money in Holland

Q.18. Comparison made between tulip and other plants

Questions 19-23: Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 2? In boxes 19-23 on your answer sheet

- TRUE: if the statement is true

- FALSE: if the statement is false

- NOT GIVEN: if the information is not given in the passage

Q.19. In 1624, all the tulip collection belonged to a man in Amsterdam.

Q.20. Tulip was first planted in Holland according to this passage.

Q.21. Popularity of Tulip in Holland was much higher than any other countries in 17th century.

Q.22. Holland was the most wealthy country in the world in 17th century.

Q.23. From 1630, Amsterdam Stock Exchange started to regulate Tulips exchange market.

Questions 24-27: Summary

Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage, using no more than two words from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 24-27 on your answer sheet.

Dutch concentrated on gaining independence by ____24_____ against Spain in the early 17th century; consequently spare resources entered the area of ____25_____ . Prosperous traders demonstrated their status by building great ____26_____ and with gardens in surroundings. Attracted by the success of profit on tulip, traders kept looking for ____27_____ and speculator for sale.

Section - 3

(A) Our mother may have told you the secret to getting what you ask for was to say please. The reality is rather more surprising. Adam Dudding talks to a psychologist who has made a life’s work from the science of persuasion. Some scientists peer at things through high-powered microscopes. Others goad rats through mazes, or mix bubbling fluids in glass beakers. Robert Cialdini, for his part, does curious things with towels, and believes that by doing so he is discovering important insights into how society works.

(B) Cialdini’s towel experiments (more of them later), are part of his research into how we persuade others to say yes. He wants to know why some people have a knack for bending the will of others, be it a telephone cold-caller talking to you about timeshares, or a parent whose children are compliant even without threats of extreme violence. While he’s anxious not to be seen as the man who’s written the bible for snake-oil salesmen, for decades the Arizona State University social psychology professor has been creating systems for the principles and methods of persuasion, and writing bestsellers about them. Some people seem to be born with the skills; Cialdini’s claim is that by applying a little science, even those of US who aren’t should be able to get our own way more often. "All my life I’ve been an easy mark for the blandishment of salespeople and fundraisers and I’d always wondered why they could get me to buy things I didn’t want and give to causes I hadn’t heard of," says Cialdini on the phone from London, where he is plugging his latest book.

(C) He found that laboratory experiments on the psychology of persuasion were telling only part of the story, so he began to research influence in the real world, enrolling in sales-training programmes: "I learn how to sell automobiles from a lot, how to sell insurance from an office, how to sell encyclopedias door to door." He concluded there were six general "principles of influence" and has since put them to the test under slightly more scientific conditions. Most recently, that has meant messing about with towels. Many hotels leave a little card in each bathroom asking guests to reuse towels and thus conserve water and electricity and reduce pollution. Cialdini and his colleagues wanted to test the relative effectiveness of different words on those cards. Would guests be motivated to cooperate simply because it would help save the planet, or were other factors more compelling? To test this, the researchers changed the card’s message from an environmental one to the simple (and truthful) statement that the majority of guests at the hotel had reused their towel at least once. Guests given this message were 26% more likely to reuse their towels than those given the old message. In Cialdini’s book "Yes! 50 Secrets from the Science of Persuasion", co-written with another social scientist and a business consultant, he explains that guests were responding to the persuasive force of "social proof’, the idea that our decisions are strongly influenced by what we believe other people like US are doing.

(D) So much for towels. Cialdini has also learnt a lot from confectionery. Yes! cites the work of New Jersey behavioural scientist David Strohmetz, who wanted to see how restaurant patrons would respond to a ridiculously small favour from their food server, in the form of an after-dinner chocolate for each diner. The secret, it seems, is in how you give the chocolate. When the chocolates arrived in a heap with the bill, tips went up a miserly 3% compared to when no chocolate was given. But when the chocolates were dropped individually in front of each diner, tips went up 14%. The scientific breakthrough, though, came when the waitress gave each diner one chocolate, headed away from the table then doubled back to give them one more each, as if such generosity had only just occurred to her. Tips went up 23%. This is "reciprocity" in action: we want to return favours done to US, often without bothering to calculate the relative value of what is being received and given.

(E) Geeling Ng, operations manager at Auckland's Soul Bar, says she’s never heard of Kiwi waiting staff using such a cynical trick, not least because New Zealand tipping culture is so different from that of the US: "If you did that in New Zealand, as diners were leaving they'd say 'can we have some more?" ' But she certainly understands the general principle of reciprocity. The way to a diner's heart is "to give them something they're not expecting in the way of service. It might be something as small as leaving a mint on their plate, or it might be remembering that last time they were in they wanted their water with no ice and no lemon. "In America it would translate into an instant tip. In New Zealand it translates into a huge smile and thank you." And no doubt, return visits.

The Five principles of persuasion

(F) Reciprocity: People want to give back to those who have given to them. The trick here is to get in first. That’s why charities put a crummy pen inside a mailout, and why smiling women in supermarkets hand out dollops of free food. Scarcity: People want more of things they can have less of. Advertisers ruthlessly exploit scarcity ("limit four per customer", "sale must end soon"), and Cialdini suggests parents do too: "Kids want things that are less available, so say ’this is an unusual opportunity; you can only have this for a certain time’."

(G) Authority: We trust people who know what they’re talking about. So inform people honestly of your credentials before you set out to influence them. "You’d be surprised how many people fail to do that," says Cialdini. "They feel it’s impolite to talk about then expertise." In one study, therapists whose patients wouldn’t do then exercises were advised to display then qualification certificates prominently. They did, and experienced an immediate leap in patient compliance.

(H) Commitment/consistency: We want to act in a way that is consistent with the commitments we have already made. Exploit this to get a higher sign-up rate when soliciting charitable donations. First ask workmates if they think they will sponsor you on your egg-and-spoon marathon. Later, return with the sponsorship form to those who said yes and remind them of their earlier commitment/

(I) Liking: We say yes more often to people we like. Obvious enough, but reasons for "liking" can be weird. In one study, people were sent survey forms and asked to return them to a named researcher. When the researcher gave a fake name resembling that of the subject (eg, Cynthia Johnson is sent a survey by "Cindy Johansen"), surveys were twice as likely to be completed. We favour people who resemble US, even if the resemblance is as minor as the sound of their name.

(J) Social proof: We decide what to do by looking around to see what others just like US are doing. Useful for parents, says Cialdini. "Find groups of children who are behaving in a way that you would like your child to, because the child looks to the side, rather than at you." More perniciously, social proof is the force underpinning the competitive materialism of "keeping up with the Joneses"

Questions 28-31: Choose the correct letter. A, B, c or D. Write your answers in boxes 37-40 on your answer sheet.

Q.28. The main purpose of Ciadini’s research of writing is to

(a) explain the reason way researcher should investigate in person

(b) explore the secret that why some people become the famous sales person

(c) help people to sale products

(d) prove maybe there is a science in the psychology of persuasion

Q.29. Which of statement is CORRECT according to Ciadini‘s research methodology

(a) he checked data in a lot of latest books

(b) he conducted this experiment in laboratory

(c) he interviewed and contact with many sales people

(d) he made lot phone calls collecting what he wants to know

Q.30. Which of the followings is CORRECT according to towel experiment in the passage

(a) Different hotel guests act in a different response

(b) Most guests act by idea of environment preservation

(c) more customers tend to cooperate as the message requires than simply act environmentally

(d) people tend to follow the hotel’s original message more

Q.31. Which of the followings is CORRECT according to the candy shop experiment in the passage?

(a) Presenting way affects diner’s tips

(b) Regular customer gives tips more than irregulars

(c) People give tips only when offered chocolate

(d) Chocolate with bill got higher tips

Questions 32-35: Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 3? In boxes 32-35 on your answer sheet, write

- TRUE: if the statement is true

- FALSE: if the statement is false

- NOT GIVEN: if the information is not given in the passage

Q.32. Robert Cialdini experienced "principles of influence" himself in realistic life.

Q.33. Principle of persuasion has different types in different countries.

Q.34. In New Zealand, people tend to give tips to attendants after being served a chocolate.

Q.35. Elder generation of New Zealand is easily attracted by extra service of restaurants by principle of reciprocity.

Questions 36-40: Use the information in the passage to match the category (listed A-E) with correct description below. Write the appropriate letters A-E in boxes 32-37 on answer sheet.

NB: You may use any letter more than once.

(a) Reciprocity of scarcity

(b) Authority

(c) previous comment

(d) Liking

Q.36. Some expert may reveal qualification in front of clients.

Q.37. Parents tend to say something that other kids are doing the same.

Q.38. Advertisers ruthlessly exploit the limitation of chances

Q.39. Use a familiar name in a survey.

Q.40. Ask colleagues to offer a helping hand

Answers

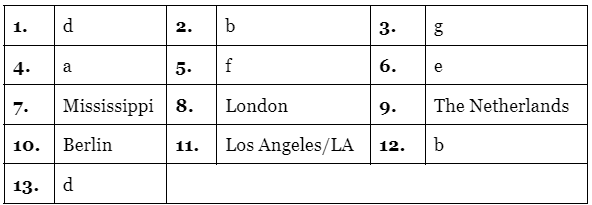

Section - 1

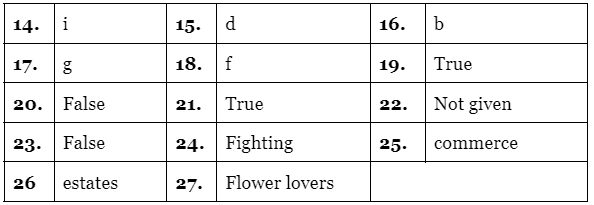

Section - 2

Section - 2

Section - 3