Reading for IELTS Academic Practice Test- 19 | Reading Practice Tests for IELTS Academic PDF Download

Section - 1

(A) It’s Britain's dodo, called interrupted brome because of its gappy seed-head, this unprepossessing grass was found nowhere else in the world. Sharp-eyed Victorian botanists were the first to notice it, and by the 1920s the oddlooking grass had been found across much of southern England. Yet its decline was just as dramatic. By 1972 it had vanished from its last toehold-two hay fields at Pampisford, near Cambridge. Even the seeds stored at the Cambridge University Botanic Garden as an insurance policy were dead, having been mistakenly kept at room temperature. Botanists mourned: a unique living entity was gone forever.

(A) It’s Britain's dodo, called interrupted brome because of its gappy seed-head, this unprepossessing grass was found nowhere else in the world. Sharp-eyed Victorian botanists were the first to notice it, and by the 1920s the oddlooking grass had been found across much of southern England. Yet its decline was just as dramatic. By 1972 it had vanished from its last toehold-two hay fields at Pampisford, near Cambridge. Even the seeds stored at the Cambridge University Botanic Garden as an insurance policy were dead, having been mistakenly kept at room temperature. Botanists mourned: a unique living entity was gone forever.

(B) Yet reports of its demise proved premature. Interrupted brome has come back from the dead, and not through any fancy genetic engineering. Thanks to one green-fingered botanist, interrupted brome is alive and well and living as a pot plant. Britain’s dodo is about to become a phoenix, as conservationists set about relaunching its career in the wild.

(C) At first, Philip Smith was unaware that the scrawny pots of grass on his bench were all that remained of a uniquely British species. But when news of the "extinction" of Bromus interruptus finally reached him, he decided to astonish his colleagues. He seized his opportunity at a meeting of the Botanical Society of the British Isles in Manchester in 1979, where he was booked to talk about his research on the evolution of the brome grasses. It was sad, he said, that interrupted brome had become extinct, as there were so many interesting questions botanists could have investigated. Then he whipped out two enormous pots of it. The extinct grass was very much alive.

(D) It turned out that Smith had collected seeds from the brome’s last refuge at Pampisford in 1963, shortly before the species disappeared from the wild altogether. Ever since then, Smith had grown the grass on, year after year. So in the end the hapless grass survived not through some high-powered conservation scheme or fancy genetic manipulation, but simply because one man was interested in it. As Smith points out, interrupted brome isn’t particularly attractive and has no commercial value. But to a plant taxonomist, that’s not what makes a plant interesting.

(E) The brome’s future, at least in cultivation, now seems assured. Seeds from Smith’s plants have been securely stored in the state-of-the-art Millennium Seed Bank at Wakehurst Place in Sussex. And living plants thrive at the botanic gardens at Kew, Edinburgh and Cambridge. This year, "bulking up" is under way to make sure there are plenty of plants in all the gardens, and sackfuls of seeds are being stockpiled at strategic sites throughout the country.

(F) The brome’s relaunch into the British countryside is next on the agenda. English Nature has included interrupted brome in its Species Recovery Programme, and it is on track to be reintroduced into the agricultural landscape, if friendly farmers can be found. Alas, the grass is neither pretty nor useful-in fact, it is undeniably a weed, and a weed of a crop that nobody grows these days, at that. The brome was probably never common enough to irritate farmers, but no one would value it today for its productivity or its nutritious qualities. As a grass, it leaves agriculturalists cold. So where did it come from? Smith’s research into the taxonomy of the brome grasses suggests that interruptus almost certainly mutated from another weedy grass, soft brome, hordeaceus. So close is the relationship that interrupted brome was originally deemed to be a mere variety of soft brome by the great Victorian taxonomist Professor Hackel. But in 1895, George Claridge Druce, a 45-year-old Oxford pharmacist with a shop on the High Street, decided that it deserved species status, and convinced the botanical world. Druce was by then well on his way to fame as an Oxford don, mayor of the city, and a fellow of the Royal Society. A poor boy from Northamptonshire and a self-educated man, Druce became the leading field botanist of his generation. When Drnce described a species, botanists took note.

(H) The brome’s parentage may be clear, but the timing of its birth is more obscure. According to agricultural historian Joan Thirsk, sainfoin and its friends made their first modest appearance in Britain in the early 1600s. Seeds brought in from the Continent were sown in pastures to feed horses and other livestock. But in those early days, only a few enthusiasts-mostly gentlemen keen to pamper theft best horses—took to the new crops.

(I) Although the credit for the "discovery" of interrupted brome goes to a Miss A. M. Barnard, who collected the first specimens at Odsey, Bedfordshire, in 1849. The grass had probably lurked undetected in the English countryside for at least a hundred years. Smith thinks the botanical dodo probably evolved in the late 17th or early 18th century, once sainfoin became established.

(J) Like many once-common arable weeds, such as the corncockle, interrupted brome seeds cannot survive long in the soil. Each spring, the brome relied on farmers to resow its seeds; in the days before weedkillers and sophisticated seed sieves, an ample supply would have contaminated stocks of crop seed. But fragile seeds are not the brome’s only problem: this species is also reluctant to release its seeds as they ripen. Show it a ploughed field today and this grass will struggle to survive, says Smith. It will be difficult to establish in today’s "improved" agricultural landscape, inhabited by notoriously vigorous competitors.

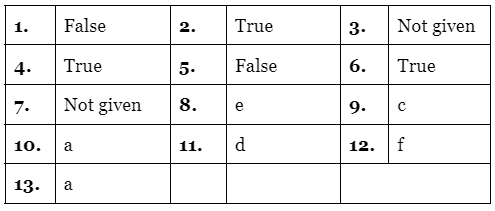

Questions 1-7: Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 1 In boxes 1-7 on your answer sheet.

- TRUE if the statement is true

- FALSE if the statement is false

- NOT GIVEN if the information is not given in the passage

Q.1. The name for interrupted brome is very special as its head shaped like a sharp eye

Q.2. Interrupted brome thought to become extinct because there were no live seed even in a labs condition.

Q.3. Philip Smith comes from University of Cambridge.

Q.4. Reborn of the interrupted brome is attributed more to scientific meaning than seemingly aesthetic or commercial ones

Q.5. English nature will operate to recover interrupted brome on the success of survival in Kew.

Q.6. Interrupted Brome grow poorly in some competing modern agricultural environment with other plants

Q.7. Media publicity plays a significant role to make interrupted brome continue to exist.

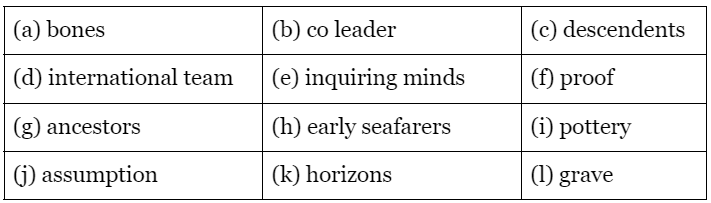

Questions 8-13: Use the information in the passage to match the people (listed A-F) with opinions or deeds below. Write the appropriate letters A-F in boxes 8-13 on your answer sheet.

NB: you may use any letter more than once

(a) George Claridge Druce

(b) Nathaniel Fiennes

(c) Professor Hackel

(d) A. M. Barnard

(e) Philip Smith

(f) Joan Thirsk Choose the people who

Q.8. reestablished the British unique plants

Q.9. identified the interrupted brome as just to its parent brome

Q.10. gave an independent taxonomy place to interrupted brome

Q.11. discovered and picked the first sample of interrupted brome

Q.12. recorded the first ’show up’ of sainfoin plants in Britain

Q.13. collected the last seeds just before its extinction

Section- 2

(A) Stories and poems aimed at children have an exceedingly long history: lullabies, for example, were sung in Roman times, and a few nursery games and rhymes are almost as ancient. Yet so far as written-down literature is concerned, while there were stories in print before 1700 that children often seized on when they had the chance, such as translations of Aesop’s fables, fairy-stories and popular ballads and romances, these were not aimed at young people in particular. Since the only genuinely child-oriented literature at this time would have been a few instructional works to help with reading and general knowledge, plus the odd Puritanical tract as an aid to morality, the only course for keen child readers was to read adult literature. This still occurs today, especially with adult thrillers or romances that include more exciting, graphic detail than is normally found in the literature for younger readers.

(A) Stories and poems aimed at children have an exceedingly long history: lullabies, for example, were sung in Roman times, and a few nursery games and rhymes are almost as ancient. Yet so far as written-down literature is concerned, while there were stories in print before 1700 that children often seized on when they had the chance, such as translations of Aesop’s fables, fairy-stories and popular ballads and romances, these were not aimed at young people in particular. Since the only genuinely child-oriented literature at this time would have been a few instructional works to help with reading and general knowledge, plus the odd Puritanical tract as an aid to morality, the only course for keen child readers was to read adult literature. This still occurs today, especially with adult thrillers or romances that include more exciting, graphic detail than is normally found in the literature for younger readers.

(B) By the middle of the 18th century there were enough eager child readers, and enough parents glad to cater to this interest, for publishers to specialize in children’s books whose first aim was pleasure rather than education or morality. In Britain, a London merchant named Thomas Boreham produced Cajanus, The Swedish Giant in 1742, while the more famous John Newbery published A Little Pretty Pocket Book in 1744.1ts contents rhymes, stories, children’s games plus a free gift (‘A ball and a pincushion’) in many ways anticipated the similar lucky-dip contents of children’s annuals this century. It is a tribute to Newbery’s flair that he hit upon a winning formula quite so quickly, to be pirated almost immediately in America.

(C) Such pleasing levity was not to last. Influenced by Rousseau, whose (1762) decreed that all books for children save Robinson Crusoe were a dangerous diversion, contemporary critics saw to it that children’s literature should be instructive and uplifting. Prominent among such voices was Mrs. Sarah Trimmer, whose magazine The Guardian of Education (1802) carried the first regular reviews of children’s books. It was she who condemned fairy-tales for their violence and general absurdity; her own stories, Fabulous Histories (1786) described talking animals who were always models of sense and decorum.

(D) So the moral story for children was always threatened from within, given the way children have of drawing out entertainment from the sternest moralist. But the greatest blow to the improving children’s book was to come from an unlikely source indeed: early 19th-century interest in folklore. Both nursery rhymes, selected by James Orchard Halliwell for a folklore society in 1842, and collection of fairy-stories by the scholarly Grimm brothers, swiftly translated into English in 1823, soon rocket to popularity with the young, quickly leading to new editions, each one more child-centered than the last. From now on younger children could expect stories written for their particular interest and with the needs of their own limited experience of life kept well to the fore.

(E) What eventually determined the reading of older children was often not the availability of special children’s literature as such but access to books that contained characters, such as young people or animals, with whom they could more easily empathize, or action, such as exploring or fighting, that made few demands on adult maturity or understanding.

(F) The final apotheosis of literary childhood as something to be protected from unpleasant reality came with the arrival in the late 1930s of child-centered bestsellers intend on entertainment at its most escapist. In Britain novelist such as Enid Blyton and Richmal Crompton described children who were always free to have the most unlikely adventures, secure in the knowledge that nothing bad could ever happen to them in the end. The fact that war broke out again during her books’ greatest popularity fails to register at all in the self-enclosed world inhabited by Enid Blyton’s young characters. Reaction against such dream-worlds was inevitable after World War II, coinciding with the growth of paperback sales, children’s libraries and a new spirit of moral and social concern. Urged on by committed publishers and progressive librarians, writers slowly began to explore new areas of interest while also shifting the settings of their plots from the middle-class world to which their chiefly adult patrons had always previously belonged.

(G) Critical emphasis, during this development, has been divided. For some the most important task was to rid children’s books of the social prejudice and exclusiveness no longer found acceptable. Others concentrated more on the positive achievements of contemporary children’s literature. That writers of these works are now often recommended to the attentions of adult as well as child readers echoes the 19th-century belief that children’s literature can be shared by the generations, rather than being a defensive barrier between childhood and the necessary growth towards adult understanding.

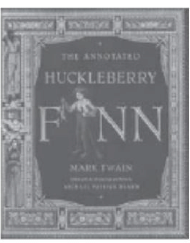

Questions 14-18: Complete the table below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from Reading Passage 2 for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 14-18 on your answer sheet.

Questions 19-21: Look at the following people and the list of statements below. Match each person with the correct statement. Write the correct letter A-E in boxes 19-21 on your answer sheet

List of statements

(a) Wrote criticisms of children’s literature

(b) Used animals to demonstrate the absurdity of fairy tales

(c) Was not a writer originally

(d) Translated a book into English

(e) Didn’t write in the English language

Q.19. Thomas Boreham

Q.20. Mrs. Sarah trimmer

Q.21. Grimm Brothers

Questions 22-26: Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 2? In boxes 22-26 on your answer sheet write

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

Q.22. Children didn’t start to read books until 1700.

Q.23. Sarah Trimmer believed that children’s books should set good examples.

Q.24. Parents were concerned about the violence in children’s books.

Q.25. An interest in the folklore changed the direction of the development of children’s books.

Q.26. Today children’s book writers believe their works should appeal to both children and adults.

Section - 3

(A) Much of the thrill of venturing to the far side of the world rests on the romance of difference. So one feels certain sympathy for Captain James Cook on the day in 1778 that he ’’discovered” Hawaii. Then on his third expedition to the Pacific, the British navigator had explored scores of islands across the breadth of the sea, from lush New Zealand to the lonely wastes of Easter Island. This latest voyage had taken him thousands of miles north from the Society Islands to an irchipelago so remote that even the old Polynesians back on Tahiti knew nothing about it. Imagine Cook’s surprise, then, when the natives of Hawaii came paddling out in their canoes and greeted him in a familiar tongue, one he had heard on virtually every mote of inhabited land he had visited. Marveling at the ubiquity of this Pacific language and culture, he later wondered in his journal: "How shall we account for this Nation spreading itself so far over this vast ocean?”

(B) That question, and others that flow from it, has tantalized inquiring minds for centuries: Who were these amazing seafarers? Where did they come from, starting more than 3,000 years ago? And how could a Neolithic people with simple canoes and no navigation gear manage to find, let alone colonize, hundreds of far-flung island specks scattered across an ocean that spans nearly a third of the globe? Answers have been slow in coming. But now a startling archaeological find on the island of Efate, in the Pacific nation of Vanuatu, has revealed an ancient seafaring people, the distant ancestors of today’s Polynesians, taking their first steps into the unknown. The discoveries there have also opened a window into the shadowy world of those early voyagers.

(C) ’’What we have is a first-or second-generation site containing the graves of some of the Pacific’s first explorers," says Spriggs, professor of archaeology at the Australian National University and co-leader of an international team excavating the site. It came to light only by luck. A backhoe operator, digging up topsoil on the grounds of a derelict coconut plantation, scraped open a grave— the first of dozens in a burial ground some 3,000 years old. It is the oldest cemetery ever found in the Pacific islands, and it harbors the bones of an ancient people archaeologists call the Lapita, a label that derives from a beach in New Caledonia where a landmark cache of their pottery was found in the 1950s.

(D) They were daring blue-water adventurers who oved the sea not just as explorers but also as pioneers, bringing along everything they would need to build new lives—their families and livestock, taro seedlings and stone tools. Within the span of a few centuries the Lapita stretched the boundaries of their world from the jungle-clad volcanoes of Papua New Guinea to the loneliest coral outliers of Tonga, at least 2,000 miles eastward in the Pacific. Along the way they explored millions of square miles of unknown sea, discovering and colonizing scores of tropical islands never before seen by human eyes: Vanuatu, New Caledonia, Fiji, Samoa. It was their descendants, centuries later, who became the great Polynesian navigators we all tend to think of: the Tahitians and Hawaiians, the New Zealand Maori, and the curious people who erected those statues on Easter Island. But it was the Lapita who laid the foundation—who bequeathed to the islands the language, customs, and cultures that their more famous descendants carried around the Pacific.

(E) While the Lapita left a glorious legacy, they also left precious few clues about themselves. A particularly intriguing clue comes from chemical tests on the teeth of several skeletons. Then as now, the food and water you consume as a child deposits oxygen, carbon, strontium, and other elements in your still-forming adult teeth. The isotope signatures of these elements vary subtly from place to place, so that if you grow up in, say, Buffalo, New York, then spend your adult life in California, tests on the isotopes in your teeth will always reveal your eastern roots. Isotope analysis indicates that several of the Lapita buried on Efate didn’t spend their childhoods here but came from somewhere else. And while isotopes can’t pinpoint their precise island of origin, this much is clear: At some point in their lives, these people left the villages of their birth and made a voyage by seagoing canoe, never to return. DNA teased from these ancient bones may also help answer one of the most puzzling questions in Pacific anthropology: Did all Pacific islanders spring from one source or many? Was there only one outward migration from a single point in Asia, or several from different points? "This represents the best opportunity we’ve had yet," says Spriggs, "to find out who the Lapita actually were, where they came from, and who their closest descendants are today."

(F) There is one stubborn question for which archaeology has yet to provide any answers: How did the Lapita accomplish the ancient equivalent of a moon landing, many times over? No one has found one of their canoes or any rigging, which could reveal how the canoes were sailed. Nor do the oral histories and traditions of later Polynesians offer any insights. "All we can say for certain is that the Lapita had canoes that were capable of ocean voyages, and they had the ability to sail them," says Geoff Irwin, a professor of archaeology at the University of Auckland and an avid yachtsman. Those sailing skills, he says, were developed and passed down over thousands of years by earlier mariners who worked their way through the archipelagoes of the western Pacific making short crossings to islands within sight of each other. The real adventure didn’t begin, however, until their Lapita descendants neared the end of the Solomons chain, for this was the edge of the world. The nearest landfall, the Santa Cruz Islands, is almost 230 miles away, and for at least 150 of those miles the Lapita sailors would have been out of sight of land, with empty horizons on every side.

(G) The Lapita’s thrust into the Pacific was eastward, against the prevailing trade winds, Irwin notes. Those nagging headwinds, he argues, may have been the key to their success. ’They could sail out for days into the unknown and reconnoiter, secure in the knowledge that if they didn’t find anything, they could turn about and catch a swift ride home on the trade winds. It’s what made the whole thing work." Once out there, skilled seafarers would detect abundant leads to follow to land: seabirds and turtles, coconuts and twigs carried out to sea by the tides, and the afternoon pileup of clouds on the horizon that often betokens an island in the distance. All this presupposes one essential detail, says Atholl Anderson, professor of prehistory at the Australian National University and, like Irwin, a keen yachtsman: that the Lapita had mastered the advanced art of tacking into the wind. "And there’s no proof that they could do any such thing," Anderson says. "There has been this assumption that they must have done so, and people have built canoes to re-create those early voyages based on that assumption. But nobody has any idea what their canoes looked like or how they were rigged."

(H) However they did it, the Lapita spread themselves a third of the way across the Pacific, then called it quits for reasons known only to them. Ahead lay the vast emptiness of the central Pacific, and perhaps they were too thinly stretched to venture farther. They probably never numbered more than a few thousand in total, and in their rapid migration eastward they encountered hundreds of islands —more than 300 in Fiji alone. Supplied with such an embarrassment of riches, they could settle down and enjoy what for a time were Earth’s last Edens.

(I) Rather than give all the credit to human skill and daring, Anderson invokes the winds of chance. El Nino, the same climate disruption that affects the Pacific today, may have helped scatter the first settlers to the ends of the ocean, Anderson suggests. Climate data obtained from slow-growing corals around the Pacific and from lake-bed sediments in the Andes of South America point to a series of unusually frequent El Ninos around the time of the Lapita expansion, and again between 1,600 and 1,200 years ago, when the second wave of pioneer navigators made their voyages farther east, to the remotest comers of the Pacific. By reversing the regular east-to-west flow of the trade winds for weeks at a time, these "super El Ninos" might have sped the Pacific’s ancient mariners on long, unplanned voyages far over the horizon. The volley of El Ninos that coincided with the second wave of voyages could have been key to launching Polynesians across the wide expanse of open water between Tonga, where the Lapita stopped, and the distant archipelagoes of eastern Polynesia. "Once they crossed that gap, they could island hop throughout the region, and from the Marquesas it’s mostly downwind to Hawaii," Anderson says. It took another 400 years for mariners to reach Easter Island, which lies in the opposite direction—normally upwind. "Once again this was during a period of frequent El Nino activity."

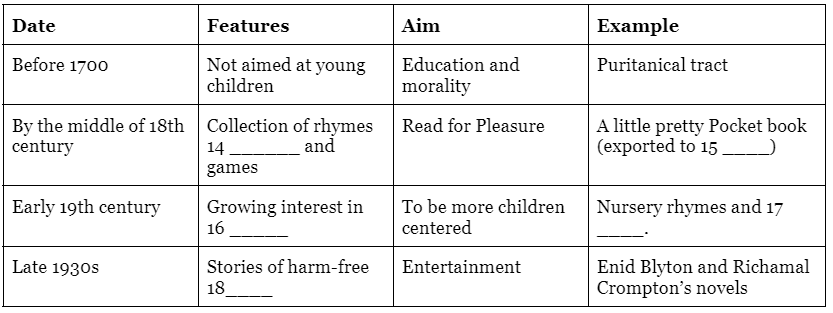

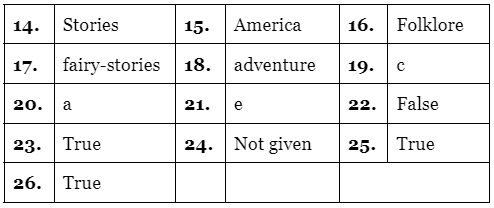

Questions 27-31: Complete the summary with the list of words A-L below. Write the correct letter A-L in boxes 27-31 on your answer sheet.

The question, arisen from Captain Cook’s expedition to Hawaii, and others derived from it, has fascinated researchers for a long time. However, a surprising archaeological find on Efate began to provide valuable information about the _____27______ On the excavating site, a _____28_____ containing _____29______ of Lapita was uncovered Later on, various researches and tests have been done to study the ancient people - Lapita and their _____30______ . How could they manage to spread themselves so far over the vast ocean? All that is certain is that they were good at canoeing. And perhaps they could take well advantage of the trade wind But there is no _____31_____ of it.

Questions 32-35: Choose the correct letter, A, B, c or D. Write your answers in boxes 32-35 on your answer sheet.

Q.32. The chemical tests indicate that

(a) the elements in one’s teeth varied from childhood to adulthood.

(b) the isotope signatures of the elements remain the same in different places,

(c) the result of the study is not fascinating.

(d) these chemicals can’t conceal one’s origin.

Q.33. The isotope analysis from the Lapita

(a) exactly locates their birth island.

(b) reveals that the Lapita found the new place via straits,

(c) helps researchers to find out answers about the islanders.

(d) leaves more new questions for anthropologists to answer.

Q.34. According paragraph F, the offspring of Lapita

(a) were capable of voyages to land that is not accessible to view.

(b) were able to have the farthest voyage of 230 miles,

(c) worked their way through the archipelagoes of the western Pacific.

(d) fully explored the horizons.

Q.35. Once out exploring the sea, the sailors

(a) always found the trade winds unsuitable for sailing.

(b) could return home with various clues.

(c) sometimes would overshoot their home port and sail off into eternity.

(d) would sail in one direction.

Questions 36-40: Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 3? In boxes 36-40 on your answer sheet, write

- TRUE if the statement is true

- FALSE if the statement is false

- NOT GIVEN if the information is not given in the passage

Q.36. The Lapita could canoe in the prevailing wind.

Q.37. It was difficult for the sailors to find ways back, once they were out.

Q.38. The reason why the Lapita stopped canoeing farther is still unknown.

Q.39. The majority of the Lapita dwelled on Fiji.

Q.40. The navigators could take advantage of El Nino during their forth voyages.

Answers

Section - 1

Section - 2

Section - 3