Reading for IELTS Academic Practice Test- 28 | Reading Practice Tests for IELTS Academic PDF Download

Section - 1

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-13 which are based on Reading Passage 1

(A) Football as we now know it developed in Britain in the 19th century, but the game is far older than this. In fact, the term has historically been applied to games played on foot, as opposed to those played on horseback, so 'football' hasn't always involved kicking a ball. It has generally been played by men, though at the end of the 17th century, games were played between married and single women in a town in Scotland. The married women regularly won.

(B) The very earliest form of football for which we have evidence is the 'tsu'chu', which was played in China and may date back 3,000 years. It was performed in front of the Emperor during festivities to mark his birthday. It involved kicking a leather ball through a 30-40cm opening into a small net fixed onto long bamboo canes - a feat that demanded great skill and excellent technique.

(C) Another form of the game, also originating from the Far East, was the Japanese 'kemari' which dates from about the fifth century and is still played today. This is a type of circular football game, a more dignified and ceremonious experience requiring certain skills, but not competitive in the way the Chinese game was, nor is there the slightest sign of struggle for possession of the ball. The players had to pass the ball to each other, in a relatively small space, trying not to let it touch the ground.

(D) The Romans had a much livelier game, 'harpastum'. Each team member had his own specific tactical assignment took a noisy interest in the proceedings and the score. The role of the feet was so small as scarcely to be of consequence. The game remained popular for 700 or 800 years, but, although it was taken to England, it is doubtful whether it can be considered as a forerunner of contemporary football.

(E) The game that flourished in Britain from the 8th to the 19th centuries was substantially different from all the previously known forms - more disorganised, more violent, more spontaneous and usually played by an indefinite number of players. Frequently, the games took the form of a heated contest between whole villages. Kicking opponents was allowed, as in fact was almost everything else.

(F) There was tremendous enthusiasm for football, even though the authorities repeatedly intervened to restrict it, as a public nuisance. In the 14th and 15th centuries, England, Scotland and France all made football punishable by law, because of the disorder that commonly accompanied it, or because the wellloved recreation prevented subjects from practising more useful military disciplines. None of these efforts had much effect.

(G) The English passion for football was particularly strong in the 16th century, influenced by the popularity of the rather better organised Italian game of 'calcio'. English football was as rough as ever, but it found a prominent supporter in the school headmaster Richard Mulcaster. He pointed out that it had positive educational value and promoted health and strength. Mulcaster claimed that all that was needed was to refine it a little, limit the number of participants in each team and, more importantly, have a referee to oversee the game.

(H) The game persisted in a disorganised form until the early 19th century, when a number of influential English schools developed thefr own adaptations. In some, including Rugby School, the ball could be touched with the hands or carried; opponents could be tripped up and even kicked. It was recognised in educational circles that, as a team game, football helped to develop such fine qualities as loyalty, selflessness, cooperation, subordination and deference to the team spirit. A 'games cult' developed in schools, and some form of football became an obligatory part of the curriculum.

(I) In 1863, developments reached a climax. At Cambridge University, an initiative began to establish some uniform standards and rules that would be accepted by everyone, but there were essentially two camps: the minority Rugby School and some others - wished to continue with their own form of the game, in particular allowing players to carry the ball. In October of the same year, eleven London clubs and schools sent representatives to establish a set of fundamental rules to govern the matches played amongst them. This meeting marked the both of the Football Association.

(J) The dispute concerning kicking and tripping opponents and carrying the ball was discussed thoroughly at this and subsequent meetings, until eventually, on 8 December, the die-hard exponents of the Rugby style withdrew, marking a final split between rugby and football. Within eight years, the Football Association already had 50 member clubs, and the first football competition in the world was started - the FA Cup.

Questions 1-7: Reading Passage 1 has ten paragraphs A-J.

List of Headings

(i) Limited success in suppressing the game

(ii) Opposition to the role of football in schools

(iii) A way of developing moral values

(iv) Football matches between countries

(v) A game that has survived

(vi) Separation into two sports

(vii) Proposals for minor improvements

(viii) Attempts to standardise the game

(ix) Probably not an early version of football

(x) A chaotic activity with virtually no rules

Choose the correct headings for paragraphs D-Jfrom the list of headings below. Write the correct number i-x in boxes 1-7 on your answer sheet.

Example Paragraph C Answer v

Q.1. Paragraph D

Q.2. Paragraph E

Q.3. Paragraph F

Q.4. Paragraph G

Q.5. Paragraph H

Q.6. Paragraph I

Q.7. Paragraph J

Questions 8-13 Complete each sentence with the correct ending A-l from the box below.

Write the correct letter A-F in boxes 8-13 on your answer sheet.

Q.8. Tsu'chu

Q.9. Kemari

Q.10. Harpastum

Q.11. From the 8th to the 19th centuries, football in the British Isles

Q.12. In the past, the authorities legitimately despised the football and acted on the belief that football

Q.13. When it was accepted in academic settings, football

Section - 2

(A) William Curry is a serious, sober climate scientist, not an art critic. But he has spent a lot of time perusing Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze's famous painting "George Washington Crossing the Delaware," which depicts a boatload of colonial American soldiers making their way to attack English and Hessian troops the day after Christmas in 1776. "Most people think these other guys in the boat are rowing, but they are actually pushing the ice away," says Curry, tapping his finger on a reproduction of the painting. Sure enough, the lead oarsman is bashing the frozen river with his boot. "I grew up in Philadelphia. The place in this painting is 30 minutes away by car. I can tell you, this kind of thing just doesn't happen anymore."

(B) But it may again soon. And ice-choked scenes, similar to those immortalized by the 16th-century Flemish painter Pieter Brueghel the Elder, may also return to Europe. His works, including the 1565 masterpiece "Hunters in the Snow," make the now-temperate European landscapes look more like Lapland. Such frigid settings were commonplace during a period dating roughly from 1300 to 1850 because much of North America and Europe was in the throes of a little ice age. And now there is mounting evidence that the chill could return. A growing number of scientists believe conditions are ripe for another prolonged cooldown, or small ice age. While no one is predicting a brutal ice sheet like the one that covered the Northern Hemisphere with glacier about 12,000 years ago, the next cooling trend could drop average temperatures 5 degrees Fahrenheit over much of the United States and 10 degrees in the Northeast, northern Europe, and northern Asia.

(C) "It could happen in 10 years," says Tenence Joyce, who cha ừ s the Woods Hole Physical Oceanography Department. "Once it does, it can take hundreds of years to reverse." And he is alarmed that Americans have yet to take the threat seriously.

(D) A drop of 5 to 10 degrees entails much more than simply bumping up the thermostat and carrying on. Both economically and ecologically, such quick, persistent chilling could have devastating consequences. A 2002 report titled "Abrupt Climate Change: Inevitable Surprises," produced by the National Academy of Sciences, pegged the cost from agricultural losses alone at $100 billion to $250 billion while also predicting that damage to ecologies could be vast and incalculable. A grim sampler: disappearing forests, increased housing expenses, dwindling freshwater, lower crop fields and accelerated species extinctions.

(E) Political changes since the last ice age could make survival far more difficult for the world's poor. During previous cooling periods, whole tribes simply picked up and moved south, but that option doesn't work in the modem, tense world of closed borders. "To the extent that abrupt climate change may cause rapid and extensive changes of fortune for those who live off the land, the inability to migrate may remove one of the major safety nets for distressed people," says the report.

(F) But first things first. Isn't the earth actually warming? Indeed it is, says Joyce. In his cluttered office, full of soft light from the foggy Cape Cod morning, he explains how such warming could actually be the surprising culprit of the next mini-ice age. The paradox is a result of the appearance over the past 30 years in the North Atlantic of huge rivers of freshwater the equivalent of a 10-foot-thick layer mixed into the salty sea. No one is certain where the fresh torrents are coming from, but a prime suspect is meltin ị Arctic ice, caused by a buildup of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that traps solar energy.

(G) The freshwater trend is major news in ocean-science circles. Bob Dickson, a British oceanographer who sounded an alarm at a February conference in Honolulu, has termed the drop in salinity and temperature in the Labrador Sea— a body of water between northeastern Canada and Greenland that adjoins the Atlantic—"arguably the largest full-depth changes observed in the modem instrumental oceanographic record." could cause a little ice age by subverting the northern

(H) The trend penetration of Gulf Stream waters. Normally, the Gulf Stream, laden with heat soaked up in the tropics, meanders up the east coasts of the United States and Canada. As it flows northward, the stream surrenders heat to the an. Because the prevailing North Atlantic winds blow eastward, a lot of the heat wafts to Europe. That's why many scientists believe winter temperatures on the Continent are as much as 36 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than those in North America at the same latitude. Frigid Boston, for example, lies at almost precisely the same latitude as balmy Rome. And some scientists say the heat also warms Americans and Canadians. "It's a real mistake to think of this solely as a European phenomenon," says Joyce.

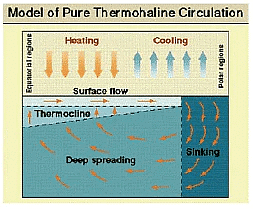

(I) Having given up its heat to the air, the now-cooler water becomes denser and sinks into the North Atlantic by a mile or more in a process oceanographers call thermohaline circulation. This massive column of cascading cold is the main engine powering a deepwater current called the Great Ocean Conveyor that snakes through all the world's oceans. But as the North Atlantic fills with freshwater, it grows less dense, making the waters carried northward by the Gulf Stream less able to sink. The new mass of relatively freshwater sits on top of the ocean like a big thermal blanket, threatening the thermohaline circulation. That in turn could make the Gulf Stream slow or veer southward. At some point, the whole system could simply shut down, and do so quickly. "There is increasing evidence that we are getting closer to a transition point, from which we can jump to a new state. Small changes, such as a couple of years of heavy precipitation or melting ice at high latitudes, could yield a big response,” says Joyce.

(J) “You have all this freshwater sitting at high latitudes, and it can literally take hundreds of years to get rid of it,” Joyce says. So while the globe as a whole gets warmer by tiny fractions of 1 degree Fahrenheit annually, the North Atlantic region could, in a decade, get up to 10 degrees colder. What worries researchers at Woods Hole is that history is on the side of rapid shutdown. They know it has happened before.

Question 14-16 Choose the correct letter, A, B, c or D. Write the correct letter in box 14-16 on your answer sheet.

Q.14. The writer mentions the paintings in the first two paragraphs to illustrate

(a) that the two paintings are immortalized.

(b) people’s different opinions.

(c) a possible climate change happened 12,000 years ago.

(d) the possibility of a small ice age in the future.

Q.15. Why is it hard for the poor to survive the next cooling period?

(a) Because people can’t remove themselves from the major safety nets.

(b) because politicians are voting against the movement.

(c) because migration seems impossible for the reason of closed borders.

(d) because climate changes accelerate the process of moving southward.

Q.16. Why is the winter temperature in continental Europe higher than that in North America?

(a) because heat is brought to Europe with the wind flow.

(b) because the eastward movement of freshwater continues,

(c) because Boston and Rome are at the same latitude.

(d) because the ice formation happens in North America.

Questions 17-21: Match each statement (Questions 17-21) with the correct person A-D in the box below. Write the correct letter A, B, C or D in boxes 17-21 on your answer sheet.

NB: You may use any letter more than once.

Q.17. A quick climate change wreaks great disruption.

Q.18. Most Americans are not prepared for the next cooling period.

Q.19. A case of a change of ocean water is mentioned in a conference.

Q.20. Global warming urges the appearance of the ice age.

Q.21. The temperature will not drop to the same degree as it used to be.

List of People

(a) Bob Dickson

(b) Terrence Joyce

(c) William Curry

(d) National Academy of Science

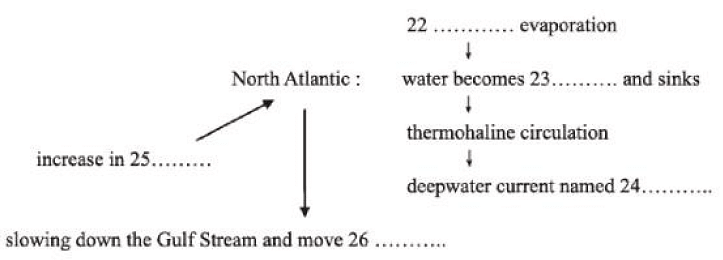

Questions 22-26 Complete the flow chart below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 22-26 on your answer sheet.

Section - 3

Historian investigates how Stalin changed the calendar to keep the Soviet people continually at work.

(A) “There are no fortresses that Bolsheviks cannot storm”. With these words, Stalin expressed the dynamic self-confidence of the Soviet Union’s Five Year Plan: weak and backward Russia was to turn overnight into a powerful modem industrial country. Between 1928 and 1932, production of coal, iron and steel increased at a fantastic rate, and new industrial cities sprang up, along with the world’s biggest dam. Everyone’s life was affected, as collectivised farming drove millions from the land to swell the industrial proletariat. Private enterprise disappeared in city and country, leaving the State supreme under the dictatorship of Stalin. Unlimited enthusiasm was the mood of the day, with the Communists believing that iron will and hard-working manpower alone would bring about a new world.

(B) Enthusiasm spread to tune itself, in the desire to make the state a huge efficient machine, where not a moment would be wasted, especially in the workplace. Lenin had already been intrigued by the ideas of the American Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1915), whose time-motion studies had discovered ways of stream-lining effort so that every worker could produce the maximum. The Bolsheviks were also great admirers of Henry Ford’s assembly line mass production and of his Fordson tractors that were imported by the thousands. The engineers who came with them to train their users helped spread what became a real cult of Ford. Emulating and surpassing such capitalist models formed part of the training of the new Soviet Man, a heroic figure whose unlimited capacity for work would benefit everyone in the dynamic new society. All this culminated in the Plan, which has been characterized as the triumph of the machine, where workers would become supremely efficient robot-like creatures.

(C) Yet this was Communism whose goals had always included improving the lives of the proletariat. One major step in that direction was the sudden announcement in 1927 that reduced the working day from eight to seven hours. In January 1929, all Industries were ordered to adopt the shorter day by the end of the Plan. Workers were also to have an extra hour off on the eve of Sundays and holidays. Typically though, the state took away more than it gave, for this was part of a scheme to increase production by establishing a three-shift system. This meant that the factories were open day and night and that many had to work at highly undesfrable hours.

(D) Hardly had that policy been announced, though, than Yuri Larin, who had been a close associate of Lenin and architect of his radical economic policy, came up with an idea for even greater efficiency. Workers were free and plants were closed on Sundays. Why not abolish that wasted day by instituting a continuous work week so that the machines could operate to their full capacity every day of the week? When Larin presented his idea to the Congress of Soviets in May 1929, no one paid much attention. Soon after, though, he got the ear of Stalin, who approved. Suddenly, in June, the Soviet press was filled with articles praising the new scheme. In August, the Council of Peoples’ Commissars ordered that the continuous work week be brought into immediate effect, during the height of enthusiasm for the Plan, whose goals the new schedule seemed guaranteed to forward.

(E) The idea seemed simple enough, but turned out to be very complicated in practice. Obviously, the workers couldn’t be made to work seven days a week, nor should their total work hours be increased. The Solution was ingenious: a new five-day week would have the workers on the job for four days, with the fifth day free; holidays would be reduced from ten to five, and the extra hour off on the eve of rest days would be abolished. Staggering the rest-days between groups of workers meant that each worker would spend the same number of hours on the job, but the factories would be working a full 360 days a year instead of 300. The 360 divided neatly into 72 five-day weeks. Workers in each establishment (at first factories, then stores and offices) were divided into five groups, each assigned a colour which appeared on the new Uninterrupted Work Week calendars distributed all over the country. Colour-coding was a valuable mnemonic device, since workers might have trouble remembering what their day off was going to be, for it would change every week. A glance at the colour on the calendar would reveal the free day, and allow workers to plan their activities. This system, however, did not apply to construction or seasonal occupations, which followed a six-day week, or to factories or mines which had to close regularly for maintenance: they also had a six-day week, whether interrupted (with the same day off for everyone) or continuous. In all cases, though, Sunday was treated like any other day.

(F) Official propaganda touted the material and cultural benefits of the new scheme. Workers would get more rest; production and employment would increase (for more workers would be needed to keep the factories running continuously); the standard of living would improve. Leisure time would be more rationally employed, for cultural activities (theatre, clubs, sports) would no longer have to be crammed into a weekend, but could flourish every day, with their facilities far less crowded. Shopping would be easier for the same reasons. Ignorance and superstition, as represented by organized religion, would suffer a mortal blow, since 80 per cent of the workers would be on the job on any given Sunday. The only objection concerned the family, where normally more than one member was working: well, the Soviets insisted, the narrow family was far less important than the vast common good and besides, arrangements could be made for husband and wife to share a common schedule. In fact, the regime had long wanted to weaken or sideline the two greatest potential threats to its total dominance: organised religion and the nuclear family. Religion succumbed, but the family, as even Stalin finally had to admit, proved much more resistant.

(G) The continuous work week, hailed as a Utopia where time itself was conquered and the sluggish Sunday abolished forever, spread like an epidemic. According to official figures, 63 per cent of industrial workers were so employed by April 1930; in June, all industry was ordered to convert during the next year. The fad reached its peak in October when it affected 73 per cent of workers. In fact, many managers simply claimed that their factories had gone over to the new week, without actually applying it. Conforming to the demands of the Plan was important; practical matters could wait. By then, though, problems were becoming obvious. Most serious (though never officially admitted), the workers hated it. Coordination of family schedules was virtually impossible and usually ignored, so husbands and wives only saw each other before or after work; rest days were empty without any loved ones to share them — even friends were likely to be on a different schedule. Confusion reigned: the new plan was introduced haphazardly, with some factories operating five-, six-and seven-day weeks at the same time, and the workers often not getting their rest days at all.

(H) The Soviet government might have ignored all that (It didn’t depend on public approval), but the new week was far from having the vaunted effect on production. With the complicated rotation system, the work teams necessarily found themselves doing different kinds of work in successive weeks. Machines, no longer consistently in the hands of people who knew how to tend them, were often poorly maintained or even broken. Workers lost a sense of responsibility for the special tasks they had normally performed.

(I) As a result, the new week started to lose ground. Stalin's speech of June 1931, which criticised the “depersonalised labor” its too hasty application had brought, marked the beginning of the end. In November, the government ordered the widespread adoption of the six-day week, which had its own calendar, with regular breaks on the 6th, 12th, 18th, 24th, and 30th, with Sunday usually as a working day. By July 1935, only 26 per cent of workers still followed the continuous schedule, and the six-day week was soon on its way out. Finally, in 1940, as part of the general reversion to more traditional methods, both the continuous five-day week and the novel six-day week were abandoned, and Sunday returned as the universal day of rest. A bold but typically illconceived experiment was at an end.

Questions 27-34: Reading Passage 2 has nine paragraphs A-I.

Choose the correct heading for each paragraph from the list of headings below.

Write the correct number I-XII in boxes 27-34 on your answer sheet.

List of Headings

(i) Benefits of the new scheme and its resistance

(ii) Making use of the once wasted weekends

(iii) Cutting work hours for better efficiency

(iv) Optimism of the great future

(v) Negative effects on production itself

(vi) Soviet Union’s five year plan

(vii) he abolishment of the new work-week scheme

(viii) The Ford model

(ix) Reaction from factory workers and their families

(x) The color-coding scheme

(xi) Establishing a three-shift system

(xii) Foreign inspiration

Q.27. Paragraph A

Q.28. Paragraph B

Q.29. Paragraph D

Q.30. Paragraph E

Q.31. Paragraph F

Q.32. Paragraph G

Q.33. Paragraph H

Q.34. Paragraph I

Questions 35-37: Choose the correct letter A, B, c or D.

Write your answers in boxes 35-37 on your answer sheet.

Q.35. According to paragraph A, Soviet’s five year plan was a success because

(a) Bolsheviks built a strong fortress.

(b) Russia was weak and backward,

(c) industrial production increased.

(d) Stalin was confident about Soviet’s potential.

Q.36. Daily working hours were cut from eight to seven to

(a) Improve the lives of all people.

(b) boost industrial productivity,

(c) get rid of undesirable work hours.

(d) change the already establish three-shift work system.

Q.37. Many factory managers claimed to have complied with the demands of the new work week because

(a) they were pressurized by the state to do so.

(b) they believed there would not be any practical problems,

(c) they were able to apply it.

(d) workers hated the new plan.

Questions 38-40: Answer the questions below using NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 38-40 on your answer sheet.

Q.38. Whose idea of continuous work week did Stalin approve and helped to implement?

Q.39. What method was used to help workers to remember the rotation of theft off days?

Q.40. What was the most resistant force to the new work week scheme?

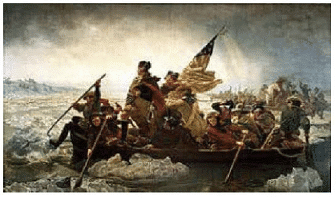

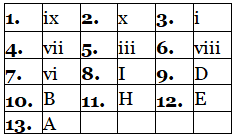

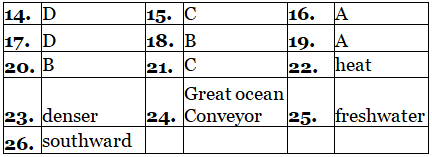

Answers

Section - 1

Section - 2

Section - 3