UPSC Exam > UPSC Notes > Philosophy Optional for UPSC > Mâyâ (Schools of Vedânta)

Mâyâ (Schools of Vedânta) | Philosophy Optional for UPSC PDF Download

Introduction

Defining Mâyâ in Vedânta

- Mâyâ, a Sanskrit term, transcends the conventional notions of "illusion" or "magic" in Vedânta.

- In Vedânta, Mâyâ represents the cosmic power that veils the true nature of Brahman, making it appear as the empirical world.

- It creates a fundamental distinction between the perceived world and the absolute truth.

- Mâyâ is described as "indescribable" or "anirvachaniya" as it is neither entirely existent nor non-existent.

Historical Significance of Mâyâ in Indian Philosophy

- Mâyâ's roots can be traced to ancient Vedic texts, initially denoting wisdom and exceptional power.

- Over time, with the Upanishads, it evolved to symbolize the principle concealing the ultimate reality.

- Adi Shankaracharya popularized Mâyâ in Advaita Vedânta, explaining how it transforms the formless Brahman into the diverse world.

- Mâyâ extends beyond Advaita, with Vishishtadvaita and Dvaita Vedânta offering nuanced interpretations.

Importance of Mâyâ in Understanding Reality and Illusion

- Mâyâ plays a pivotal role in discussions about reality's nature.

- Vedânta asserts that the perceived world, with its diversity, is a manifestation of Mâyâ and not the ultimate reality.

- Avidyâ (ignorance) is closely tied to Mâyâ, trapping individuals in the cycle of birth and death.

- The spiritual journey in Vedântic philosophy involves piercing through Mâyâ's veil to realize Brahman, the ultimate truth.

- Mâyâ helps us grasp the transient nature of the world, encouraging the pursuit of the eternal and unchanging truth.

Conceptual Foundations of Mâyâ

Etymological Origins of Mâyâ

- The term "Mâyâ" originates from "ma," signifying "to measure" or "to limit."

- Historically, it implied wisdom, skill, or extraordinary power.

- Over time, its meaning expanded to include "illusion" or "deception" in metaphysical contexts.

- Mâyâ serves as a bridge between the finite and infinite, connecting the tangible world to the intangible Brahman.

Mâyâ as a Dynamic Aspect of Brahman

- Mâyâ is more than illusion; it's considered Brahman's dynamic, creative force.

- Its interpretation evolved from the Rgveda's focus on deities' magical powers to the Upanishads' portrayal of the world as Mâyâ's illusionary manifestation.

- Mâyâ acts as the means through which the perceivable universe emanates from the unmanifest Brahman.

- This cosmic play, known as Lila, encompasses creation, preservation, and destruction under Mâyâ's influence.

The Relationship Between Brahman and Mâyâ

- Mâyâ is often seen as Brahman's Shakti (power).

- While Brahman remains changeless, formless, and beyond comprehension, Mâyâ allows the perceivable universe to manifest.

- This suggests a non-dualistic relationship where Mâyâ, as the creative power, operates under Brahman's will.

Mâyâ's Dual Nature: Creative and Veiling Aspects

- Mâyâ in Vedântic philosophy possesses a dual nature: it is both creative and veiling.

- It veils Brahman's true nature, making the unchanging reality appear as the ever-changing empirical world.

- This veiling leads to Avidyâ (ignorance), causing individuals to misperceive Brahman as the empirical world.

- Liberation is achieved by piercing through Mâyâ's illusion to realize the true nature of Brahman.

Mâyâ in Advaita Vedânta

Advaita's Non-Dualistic Framework

- Advaita Vedânta emphasizes non-duality, asserting that the ultimate reality is Brahman alone.

- All distinctions are considered illusory products of Mâyâ.

- Liberation (Moksha) is attained by dissolving dualistic notions.

The Relationship Between Mâyâ and Brahman in Advaita

- In Advaita, Mâyâ is inseparable from Brahman and is seen as the creative power of Brahman.

- It doesn't exist independently from Brahman and is compared to the heat of fire, without which fire cannot exist.

- Îúvara (cosmic controller), Âtman (pure consciousness), Jiva (individual souls), and Jagat (material world) all relate to Mâyâ differently within Advaita.

Shankara's Perspective on Mâyâ

- Shankaracharya, a renowned philosopher, distinguished between Vyavahârika (empirical reality) and Pâramârthika (ultimate reality).

- Vyavahârika is influenced by Mâyâ, while Pâramârthika is the realm of Brahman alone.

- Shankara described Mâyâ as neither real nor unreal, as it changes but is also experienced.

Critiques and Challenges to Advaita's View on Mâyâ

- Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita introduced qualified non-duality, critiquing Advaita's perspective on Mâyâ's indeterminacy.

- Madhva's Dvaita rejected Mâyâ as a mere figment, positing eternal distinction between Jiva and Brahman.

- Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna's Shunyavada challenged Mâyâ's role in obscuring Brahman, advocating emptiness as the core reality.

- Modern rationalists have questioned Mâyâ's relevance in the era of empirical science.

Mâyâ in Vishishtadvaita Vedânta

Framework of Qualified Non-Dualism

- Vishishtadvaita Vedânta advocates qualified non-dualism, emphasizing that Brahman possesses infinite attributes.

- It asserts that the world and souls are distinct from Brahman but inseparable and dependent on Him.

- Unlike Advaita, Vishishtadvaita views Mâyâ as a dependent reality, not the cause of illusion.

Ramanuja's Interpretation of Mâyâ

- In Vishishtadvaita, Mâyâ is not an illusion but a dependent reality.

- It represents the material nature of the universe and is subservient to the divine will of Îúvara (Brahman with attributes).

- Mâyâ's role is to facilitate the cosmic order and souls' karmic results.

The Role of Mâyâ in the Cosmic Order

- In Vishishtadvaita, the cosmic order (Dharma) is significant, and Mâyâ facilitates it.

- Mâyâ ensures that individuals experience the consequences of their karma, upholding the divine plan.

- It doesn't veil reality but serves as the stage for souls' evolution.

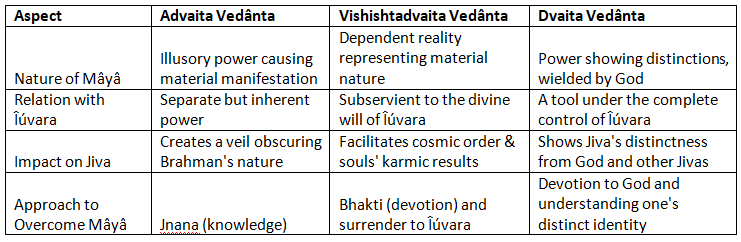

Contrasting Mâyâ in Advaita and Vishishtadvaita

- In Advaita, Mâyâ is an illusory power causing material manifestation, while in Vishishtadvaita, it's a dependent reality representing the material nature.

- The relationship between Mâyâ and Brahman/Îúvara differs, with Advaita viewing them as separate but inseparable and Vishishtadvaita as subservient to Îúvara.

- Overcoming Mâyâ in Advaita involves Jnana (knowledge), whereas in Vishishtadvaita, it's through Bhakti (devotion) and surrender to Îúvara.

Responses to Criticisms on Vishishtadvaita's View of Mâyâ

- Ramanuja addressed criticisms by emphasizing that the world's reality doesn't contradict Brahman's oneness.

- He argued that the world and souls are real but depend on Brahman for their existence.

- Mâyâ, as a dependent reality, upholds the cosmic order and serves the divine plan, refuting claims of its indescribable or unreal nature.

Mâyâ in Dvaita Vedânta

Madhva's Dualistic Doctrine

- Madhva, the principal advocate of Dvaita Vedânta, championed a resolute dualism, in stark contrast to Advaita's non-dualism.

- His philosophy centers on the eternal distinction between the individual soul (Jiva) and the supreme being (Îúvara or God).

- In Madhva's view, these two entities are unequivocally separate and will remain so.

- This doctrine firmly rejects the merging of the individual soul into the supreme consciousness, as proposed by Advaita.

Mâyâ's Role in Dvaita Clear Distinction Between God and Soul

- Dvaita conceives of Mâyâ differently from Advaita. It does not regard Mâyâ as an illusionary power.

- In Dvaita, Mâyâ is a power wielded by God, but it does not affect God in any way.

- For Madhva, Mâyâ stands as a testimony to God's power and will, revealing the distinctions among all things.

- Jivas, while influenced by Mâyâ, are distinct entities, both from God and from each other.

Reality of the World

- Unlike Advaita, Dvaita considers the world, or Jagat, to be profoundly real.

- It is not perceived as a manifestation of Mâyâ as an illusion but rather as a testament to God's creative power.

- In Dvaita, the world's reality ensures that the experiences of souls (Jivas) here have genuine consequences and implications.

Contrast Between Mâyâ and Central Concepts in Dvaita Îúvara (God)

- Îúvara is the supreme being, God, or Brahman with attributes.

- In Dvaita, Îúvara is entirely independent, in stark contrast to the world and Jivas, which are dependent realities.

- Mâyâ serves as a tool under the complete control of Îúvara, demonstrating the distinctions among all entities.

Âtman (Individual Soul)

- Âtman refers to the true, untouched soul within individuals.

- In Dvaita, Âtman is forever distinct from God, emphasizing the philosophy's dualistic core.

Jiva (Individual Soul)

- Jiva represents the individual soul entangled in the cycle of births and deaths.

- It is continually influenced by Mâyâ but remains forever distinct from God.

Jagat (Material World)

- Jagat denotes the material world created by God.

- Unlike in Advaita, where the world is considered an illusionary manifestation of Mâyâ, in Dvaita, it is real.

Comparing Mâyâ in Advaita, Vishishtadvaita, and Dvaita

Defense Against Criticisms on Dvaita's Interpretation of Mâyâ

- Madhva and his followers have robustly defended Dvaita's interpretation of Mâyâ.

- One key defense centers on God's unquestionable supremacy, which is unaltered by the concept of Mâyâ.

- In Dvaita, Mâyâ does not diminish God's power or position; instead, it reinforces the philosophy's unyielding dualism.

- A comprehensive understanding of Mâyâ helps acknowledge the distinct identity of the soul and its relationship with the world and God.

Contemporary Critiques and Interpretations of Mâyâ

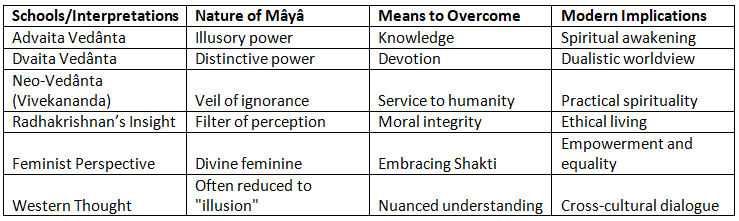

Neo-Vedânta and the Understanding of Mâyâ Swami Vivekananda's Perspective

- Swami Vivekananda, a prominent spiritual leader, introduced Neo-Vedânta, a modern interpretation of Vedânta.

- Neo-Vedânta underscores the practical aspects of Vedânta for individual growth and societal betterment.

- Vivekananda recognized Mâyâ as the "veil" that obscures divine truth, making it unrecognizable.

- He advocated for transcending Mâyâ through self-realization, emphasizing the direct experience of the divine.

- Service to humanity was promoted as a means to overcome Mâyâ, recognizing the divine presence in all beings.

Radhakrishnan's Insights on Mâyâ

- Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, a revered philosopher and India's second President, offered profound insights into Mâyâ.

- Radhakrishnan portrayed Mâyâ as a mode of human experience, functioning as a filter that colors our perception.

- He contended that Mâyâ does not render the world unreal but rather makes it appear differently than its true essence.

- Radhakrishnan advocated for a life of moral integrity as the path to see beyond Mâyâ and comprehend the ultimate truth.

Feminist Interpretations: Mâyâ as Female Principle Shakti and its Association with Mâyâ

- Shakti, the cosmic female principle symbolizing dynamic forces and empowerment, is deeply rooted in Indian culture and spirituality.

- Some interpretations link Shakti with Mâyâ, considering both as manifestations of the divine feminine.

- Shakti, like Mâyâ, both conceals and reveals, highlighting the dual nature of the divine.

- Festivals like Navaratri celebrate Shakti's power and her triumph over Mâyâ, symbolizing empowerment and equality.

Post-colonial Critique: Mâyâ and its Implications in the Modern World Interpretation of Mâyâ in Western Thought

- The colonization of India brought Indian philosophies, including Mâyâ, into Western interest and scrutiny.

- Western interpretations at times reduced Mâyâ to a mere "illusion," overlooking its depth and complexity.

- Such interpretations were occasionally used to undermine Indian thought, portraying it as mystical or escapist, lacking practical relevance.

- Modern scholars advocate for a nuanced understanding, recognizing Mâyâ's intricate role in Vedânta and its contemporary relevance.

Comparative Study: Mâyâ in Different Schools and Contemporary Interpretations

Conclusion – Mâyâ’s Evolutionary Role in Vedânta

Mâyâ’s Evolutionary Role in Vedânta

- Mâyâ, a concept of great complexity, bears significance across Vedânta traditions.

- Its origins can be traced to Vedic literature, where it initially denoted wisdom and power.

- In the Upanishads, Mâyâ evolved into a metaphysical concept, signifying the illusory nature of the world.

- In Advaita Vedânta, as advocated by Adi Shankaracharya, Mâyâ becomes an illusory force that obscures Brahman.

- Ramanuja’s Vishishtadvaita Vedânta sees Mâyâ as an attribute of Brahman, leading to a qualified non-dualism.

- Madhva’s Dvaita Vedânta distinctly separates God and soul, emphasizing dualism.

- Contemporary interpretations have further nuanced Mâyâ, including Neo-Vedânta by Swami Vivekananda and insights by Radhakrishnan.

- The Ongoing Debate: Realism Vs. Illusionism in the Context of Mâyâ

- The realism vs. illusionism debate profoundly influences Vedânta’s understanding of Mâyâ.

- Realism, as observed in Dvaita Vedânta, asserts the reality of the world and individual selves.

- Illusionism, predominantly represented by Advaita Vedânta, considers the world an illusion, with only Brahman being real.

- This debate shapes the spiritual journey of practitioners, with realists focusing on devotion and duality, while illusionists aim to dispel Mâyâ and realize Brahman.

Implications of Mâyâ for Understanding Self and Reality

- A comprehensive grasp of Mâyâ can guide one’s spiritual exploration.

- Mâyâ underscores the transient and illusory nature of the world, encouraging individuals to seek deeper truths.

- The self (Âtman) and the universe (Brahman) are interconnected through Mâyâ.

- The pursuit of self-knowledge necessitates an understanding of Mâyâ and its implications.

- Spiritual practices like meditation, devotion, and selfless service serve as tools to transcend Mâyâ.

- Renowned Indian saints, such as Kabir and Meerabai, emphasized seeing beyond Mâyâ to comprehend the true nature of the self.

The Unending Quest: Mâyâ’s Mystery in the Philosophical Landscape

- Mâyâ remains an enigmatic concept that has captivated thinkers and philosophers for centuries.

- Despite exhaustive interpretations, Mâyâ retains an air of mystery, symbolizing humanity's endeavor to comprehend the infinite.

- The quest to understand Mâyâ mirrors the broader human journey to seek meaning, purpose, and truth.

- Philosophical discussions surrounding Mâyâ exemplify humanity's ongoing exploration of existence, reality, and spirituality.

The document Mâyâ (Schools of Vedânta) | Philosophy Optional for UPSC is a part of the UPSC Course Philosophy Optional for UPSC.

All you need of UPSC at this link: UPSC

|

27 videos|168 docs

|

FAQs on Mâyâ (Schools of Vedânta) - Philosophy Optional for UPSC

| 1. What is the concept of Mâyâ in Advaita Vedânta? |  |

Ans. In Advaita Vedânta, Mâyâ is the principle of illusion or ignorance that creates the perception of duality in the world. It is seen as the power of Brahman, the ultimate reality, to manifest the universe. According to Advaita Vedânta, Mâyâ is not real but only an appearance, and the true nature of reality is non-dual consciousness.

| 2. How is Mâyâ understood in Vishishtadvaita Vedânta? |  |

Ans. In Vishishtadvaita Vedânta, Mâyâ is considered a real power or energy of Brahman, rather than an illusion. It is seen as the creative force that allows Brahman to manifest the universe while still maintaining a qualified non-dualistic relationship with it. Mâyâ is seen as an intermediary between the individual soul and Brahman, enabling the soul to experience the world.

| 3. How does Dvaita Vedânta interpret the concept of Mâyâ? |  |

Ans. In Dvaita Vedânta, Mâyâ is seen as the cosmic power of Brahman that creates and sustains the universe. However, unlike Advaita Vedânta, Dvaita Vedânta considers Mâyâ as real and not illusory. It is seen as the divine energy through which Brahman interacts with the world and the individual souls. Mâyâ is responsible for the duality and multiplicity observed in the phenomenal world.

| 4. What are some contemporary critiques and interpretations of Mâyâ? |  |

Ans. In contemporary philosophy and spirituality, there are various critiques and interpretations of Mâyâ. Some argue that Mâyâ is a metaphorical concept that represents the limitations of human perception and understanding. Others question the idea of Mâyâ as an illusion, suggesting that it may be more accurate to view it as a dynamic process of manifestation and transformation. Some also criticize the concept of Mâyâ for its potential to perpetuate a sense of separation and detachment from the world.

| 5. How does Mâyâ play an evolutionary role in Vedânta? |  |

Ans. In Vedânta, Mâyâ is seen as playing an evolutionary role by enabling the manifestation and unfolding of the universe. It is through Mâyâ that the infinite consciousness of Brahman takes on various forms and experiences. Mâyâ allows for the evolution of individual souls, their journey towards self-realization, and their eventual realization of their non-dual nature with Brahman. Thus, Mâyâ is seen as a dynamic and transformative force in the process of spiritual evolution.

Related Searches