Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 | Law Optional Notes for UPSC PDF Download

Introduction

Stealing government money by officials can often go unnoticed, much like a fish's water consumption is hard to track. This quote by Dev Dantreliya highlights the elusive nature of corruption. Corruption has deep roots in India, with opportunistic leaders using their positions for personal gain. This pervasive issue hinders progress, especially in developing countries like India and within government institutions. Even the education sector, which aims to instill ethical values, is not free from corruption's grasp. An example of this is the recent arrest of two senior officials from the Directorate of Higher Education who accepted a bribe from a professor. The fight against corruption began with laws like the Criminal Law (Amendment) Ordinance of 1944, targeting the concealment of ill-gotten property resulting from corrupt practices. In 1964, the Central Vigilance Commission was established to address corruption cases, and various state-specific vigilance commissions were created to tackle this issue.

In response to this challenge, the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 (POCA) was enacted to consolidate existing laws, combat corruption within government bodies, and prosecute public officials involved in corrupt activities. This act is a vital tool in the fight against corruption, and its effectiveness is crucial. Under this act, the Central Government has the authority to appoint judges to investigate and adjudicate cases related to offenses outlined in the Act or conspiracies to commit these offenses.

This article delves into the evolution of The Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, and its key provisions. It also discusses amendments to the legislation and important legal decisions regarding the Act.

Evolution of the Act

- Initially, matters related to bribery and corruption involving public servants within the Indian justice system were addressed by the Indian Penal Code of 1860. However, by the 1940s, it became apparent that the existing laws were insufficient to effectively address the growing challenges posed by bribery and corruption. This led to the recognition of the need for specific legislation to combat these issues, and as a response, the impressive Prevention of Corruption Act of 1947 was enacted. The 1947 Act underwent two subsequent amendments, first through the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1952 and then the Anti-Corruption Laws (Amendment) Act of 1964, both of which were based on recommendations made by the Santhanam Committee.

- As a result of this legislative evolution, the 1988 Prevention of Corruption Act, which came into effect on September 9, 1988, was born. This Act was designed to enhance the effectiveness of anti-corruption laws by expanding their scope, strengthening requirements, and making the overall resolution more practical. Its primary goal was to combat corruption within government offices and public sector organizations in India. The Prevention of Corruption Act aimed to not only identify corruption within these entities but also to prosecute and punish public officials involved in corrupt activities. Furthermore, the Act also considered individuals who aided the culprits in committing bribery or corruption offenses.

Distinctive features of the Act

The following are some of the key features of the Act:

- It has broadened the definition’s application to include terms like “public duty” and “public servant” under Section 2 of the Act’s definition clause.

- According to the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, it has transferred the burden of proof from the prosecution to the person accused of the crime.

- The Act’s requirements are very clear: an officer with at least the rank of Deputy Superintendent of Police must conduct the inquiry.

- The 1988 Act broadened the definition of “public servant” to include Central Government personnel, union territories, nationalised banks, University Grants Commission (UGC), vice-chancellors, academics, and others.

- The Act criminalises corrupt conduct like bribery, misappropriation, acquiring a monetary advantage, having assets disproportionate to income, and so on.

Important provisions of the Act

Important definitions

Section 2(b) of the Act defines “Public duty” as a duty in the execution of which the state, the public, or society at large has an interest. The term ‘state’ has a broad meaning as well. In this context, state means

- A corporation created or founded by a Central, Provincial, or State Act.

- A government authority or a body controlled or aided by a government company, as defined in Section 617 of the Companies Act of 1956.

The importance of the term “public duty” is that those who are paid by the government for doing public tasks or who otherwise conduct public obligations may also prevent corruption among public workers.

Section 2(c) of the Act defines “public servant” broadly and expressively. Thus the term includes the following:

- Any individual employed by the government, receiving government compensation, or receiving fees or commissions from the government for the performance of any public obligation;

- Any individual who works for or is compensated by a local government;

- Any employee of a firm created by or operating under a Central, Provincial, or State Act, as well as any authority, body, or company owned, controlled, or assisted by the Government, as defined in section 617 of the Companies Act, 1956.

- Any Judge, as well as anyone permitted by law to carry out adjudicatory duties on their own or as a part of any group of people;

- Any individual designated as a liquidator, receiver, or commissioner by a court of justice with the authority to carry out any function related to the administration of justice;

- Any arbitrator or other individual to whom any issue or subject has been submitted by a court of justice or by a competent public authority for judgement or report;

- Any person who occupies a position that gives him the authority to conduct an election or a portion of an election, or to compile, publish, maintain, or update an electoral roll;

- Any individual holding a position that allows or obligates them to carry out public duties;

- Anyone serving as the president, secretary, or other office-holder of a registered cooperative society engaged in agriculture, industry, trade, or banking who is currently receiving or has previously received financial aid from the Central Government, a State Government, or from any corporation created by or operating under a Central, Provincial, or State Act, as well as any authority or body owned, controlled, or assisted by the Government or a Government company as defined in Section 617 of the Companies Act, 1956

- Any individual who serves as the chairman, a member, or an employee of any Service Commission or Board, regardless of its name, or a member of any selection committee chosen by the Commission or Board to conduct any examinations or make any selections on its behalf;

- Any Vice-Chancellor, member of a governing body, professor, reader, lecturer, or other teacher or employee of any university, regardless of their title, as well as any individual whose services have been used by a university or another public authority in connection with the holding or conducting of exams;

- Any official or employee of an educational, scientific, social, cultural, or other institution, regardless of how it was founded, who is receiving or has previously received financial support from the Central Government, any State Government, a local government, or other public authority.

Whether they are public servants or not?- Minister, Chief Minister, and Prime Minister

- Ministers, Chief Ministers, and the Prime Minister fall under the category of public servants as per Clause (12) of Section 21 of the Indian Penal Code, which corresponds to Clause (c) of Section 2 in the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988. This classification is attributed to their roles and functions within the government.

- In the case of M. Karunanidhi v. Union of India (1979), the Supreme Court determined that a Minister qualifies as a public servant.

This determination was based on the following factors:- Ministers are employed by and are subject to the authority of the Governor.

- They receive compensation for their work and duties, which are carried out on behalf of the public, and their salaries are funded by public resources.

- It's important to note that while Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) are not considered public servants under Section 21 of the Indian Penal Code, they are encompassed within the scope of Clause (c) of Section 2 of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988. This implies that the definition of "public servant" in the Prevention of Corruption Act is broader and includes positions such as MLAs.

- The term "public servant" is not limited to the specific instances mentioned in the defining clause, and the courts have adopted an interpretation that allows for the inclusion of additional individuals. In the case of P.V. Narasimha Rao vs. State (1998), the definitions of "public duty" and "public servant" were subject to scrutiny. The Supreme Court's ruling clarified that these terms, "public duty" and "public servant," should be interpreted broadly. Consequently, Members of Parliament (MPs) are subject to Section 2 of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, even if authorities may not always seek authorization for their prosecution under Section 19(1) of the Act. This implies that MPs can be considered public servants under the Act.

Accepting rewards, influencing public officials, and accepting gifts

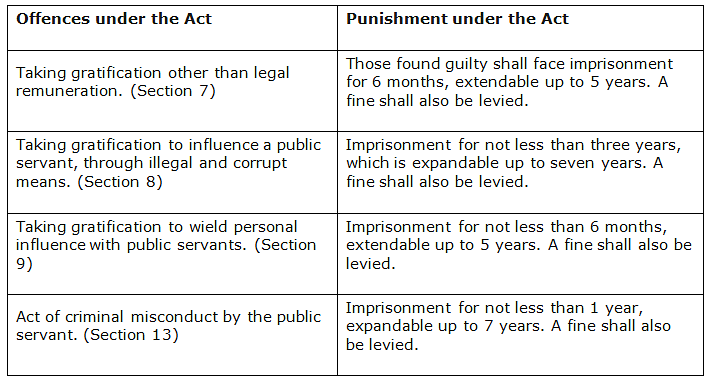

- Sections 7 to 11 of the Prevention of Corruption Act (POCA) outline offenses related to receiving gratification, influencing public officials, and accepting gifts. These offenses are categorized based on their severity. Additionally, actions such as abetment, conspiracy, agreement, and attempts to commit these offenses have been criminalized to proactively combat bribery and corruption. Various actions are classified as punishable under different sections of the Act.

- It's worth noting that these sections are currently under consideration for significant changes due to India's obligations under the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC). The existing provisions of the Prevention of Corruption Act are detailed below. Generally, these provisions involve a public servant receiving illicit remuneration in exchange for granting a favor or as an incentive or reward for their actions.

- Section 7: This section pertains to public servants receiving rewards other than their lawful salary in return for performing official acts. Importantly, gratification in this context is not limited to monetary forms; it includes non-monetary benefits. However, it is crucial that the demand for such gratification is initiated by the public servant. The mere possession of valuable property, without evidence of such demand, may not lead to guilt under Section 7.

- Section 8: This section prohibits obtaining gratification through corrupt or criminal means to influence a public servant. The term "whoever accepts or acquires, or agrees to accept, or seeks to obtain" applies to both public servants and non-public servants. The primary distinction from Section 9 is that Section 8 allows for the use of "personal influence" to gain favor or disfavor, whereas Section 9 involves "corrupt or criminal methods." Notably, "corrupt" is not defined in the Prevention of Corruption Act.

- Section 11: This section deals with a public servant receiving valuable items from individuals involved in business or transactions with the public official. To be liable under this provision, public servants must acquire something of value while performing official duties, and these advantages must primarily benefit them or another person.

- Section 12: Whoever aids any crime defined under Sections 7 to 11, regardless of whether the crime is committed as a result of their assistance, may face imprisonment for a minimum of three years and a maximum of seven years, along with an additional five years in prison.

- Section 13: This section enables the prosecution of repeat offenders and, more importantly, targets public servants who receive valuable items or financial gains through corrupt or criminal means, abuse their position as public officials to acquire such items, or obtain them for someone else without serving the public interest. Importantly, without evidence of demand, the mere possession or seizure of money during an investigation does not constitute a violation of Section 7 or Section 13(1)(d) of this Act.

- In the case of P. Satyanarayana Murthy vs. The District Inspector of Police (2015), the Supreme Court clarified that the use of corrupt or illegal means or the abuse of one's position as a public servant to gain valuable items or financial advantages cannot be considered proven in the absence of evidence of a demand for illegal gratification.

Is this Act applicable to private individuals as well

- As previously mentioned, the Prevention of Corruption Act of 1988 primarily targets public servants, but it does have some applicability to certain private individuals. While the Act predominantly addresses offenses committed by public servants, there are specific situations where it extends to private individuals.

- Section 8: This section outlines circumstances in which a person seeks illegal gratification to influence a public servant. Therefore, if a person other than a public servant receives an unlawful payment under the criteria specified in Section 8 of the Act (which mirror those in Section 7), that individual is equally liable for the offense. The Act prescribes penalties ranging from six months to five years of imprisonment, in addition to a fine. Similarly, the Act prohibits actions taken by individuals who leverage their personal influence with public servants to obtain illegal gratification.

- In essence, Section 8 applies to anyone who has connections to public servants engaged in corrupt activities. This provision is crucial in a context where there is a prevalent "V.I.P. mentality" in the country, with many individuals claiming relationships with public servants and attempting to gain unlawful advantages in various areas. Additionally, this regulation discourages public officials from acquiring illicit benefits by concealing their identities behind another person's identity.

Whether it is illegal to abate some offences

- If a public employee who has been charged with an offence under Sections 8 or 9 aids and abets the actions of those other people, the act of aiding is itself criminal under the Act, Whether the crime was done as a result of the abetment, in this case, is irrelevant. The abettor will be subject to a fine in addition to a sentence of imprisonment that must be at least six months long but may not exceed five years.

- As a result, the abettor will face the same form of penalty. It is a positive feature when it comes to preventing people from assisting others to commit crimes under the Act, as it provides the same level of penalty for the abettor regardless of whether the offence aided is committed or not. Similarly, Section 12 makes it a crime to aid and abet an offence described in Sections 7 and 11. Section 7 makes it a crime for a public officer to accept a reward other than lawful pay in exchange for performing an official act.

- Section 11 makes criminal acts of a public officer getting valuable things without compensation from the person involved in the proceeding or transaction undertaken by such a public servant.

Investigation

- Investigations are a crucial aspect of the criminal justice system, typically carried out by the police. Their primary responsibility is to gather evidence and identify the actual perpetrators of crimes. However, the broad powers granted to the police can sometimes be susceptible to abuse, making it important to scrutinize these powers, as they pertain to the administration and conduct of public servants. Not all police officers are allowed to conduct investigations for this reason. Only officers of a certain rank are authorized to handle these matters.

- Section 17 of the Act specifies who is authorized to conduct investigations under the Prevention of Corruption Act. The following individuals are granted this authority:

- Delhi Special Police Establishment (CBI): An officer holding the rank of Inspector of Police or higher.

- Metropolitan Areas (e.g., Bombay, Madras, Calcutta): An official with the rank of Assistant Commissioner of Police or higher.

- Elsewhere: An officer holding the rank of Deputy Superintendent of Police or higher is authorized.

- However, no authorized official can conduct investigations or make arrests without obtaining an order from the Metropolitan Magistrate or Magistrate of First Class. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, they may arrest the accused without a warrant from such a Magistrate. This arrangement ensures that not all police officers are empowered to investigate corruption allegations under the Prevention of Corruption Act of 1988. Only designated police personnel with specific ranks are allowed to conduct investigations related to these offenses.

- This structure creates an effective balance between the rights of the accused and the interests of the prosecution, preventing undue harassment of public servants by the police. It serves as an efficient framework for controlling the problem of corruption and upholding the rule of law to achieve the noble goal of natural justice.

Restriction on the investigation in certain cases

Section 17A of the Amendment Act 2018 stipulates that no one may investigate an alleged offence if it involves a recommendation/decision made by a public worker in the course of his official responsibilities.

If such an inquiry is to be performed, the following approvals are required:

- Approval of the Central Government is required for offences involving Union matters.

- For offences involving the conduct of state affairs, state government approval is required.

However, if an arrest is conducted on the scene and the offender admits to committing an offence, no such clearance is necessary.

The authority to examine bankers’ books

Section 18 of the Act stipulates that if the investigation officer believes that the bankers’ records need to be examined for the purpose of inquiry, the officer may examine them. This power of inspection extends beyond the offender’s bank accounts and includes the authority to search the bank accounts of anybody whom the officer suspects of holding money on behalf of the criminal.

The function of the bribe provider and the presumption of taint

According to Section 20 of the POCA, there is a presumption that any expensive item or pleasure discovered in the hands of a person under investigation was obtained for the reasons described in Section 7 of the Act. This is a rebuttable presumption, and the individual under investigation would have the burden of proving that the valued item or gratification was not obtained in connection with the Act’s violation. Accordingly, a person under investigation would be found guilty if no evidence was presented to refute the assumption, as was decided in the case of M. Narsinga Rao vs State of Andhra Pradesh (2001).

Section 24 of the POCA grants immunity to the bribe giver and states that the bribe giver’s confession will not expose him to prosecution. The immunity granted to bribe providers under this rule has been seen as a fundamental weakness as well as contradictory with international norms.

Punishment or penalty under the Act

- The imposition of penalties or sentences plays a pivotal role in the criminal justice system. Without consequences or retribution, the objectives of the law cannot be realized. Penalties and punishments serve as a deterrent for potential wrongdoers, and their severity, amount, and duration influence the rehabilitation of the accused. Under the Prevention of Corruption Act of 1988, the standard punishment for lower-level offenses (under Sections 7 to 12) ranges from three to seven years in prison, in addition to a fine. More serious offenses, such as those outlined in Section 13, incur harsher penalties.

- Specifically, the offense of criminal misconduct, as defined in Section 13, results in imprisonment for a period of no less than four years but not exceeding ten years, along with a fine. Individuals committing the offenses outlined in Section 14, which pertain to the habitual commission of offenses specified in Sections 8, 9, and 12, are subject to a five-year prison term, extendable to 10 years, and are required to pay a court-determined fine. The Act also criminalizes attempts to commit offenses, stating that anyone attempting to engage in offenses mentioned in Section 13(c) or (d) of subsection (1) faces a minimum two-year imprisonment, extendable to five years, along with a fine.

- Additionally, the Act mandates that the court assess the value or financial interest in the object or property at the center of the committed offense. Previously, the Prevention of Corruption Act of 1988 provided for relatively short prison terms, which were inadequate in effectively combatting corruption. The Lokpal and Lokayuktas Act of 2013 later extended these sentences. This extension was prompted by mounting pressure from various sectors of society to combat the scourge of corruption. Civil society, in recent times, has played a significant role in generating strong public sentiment against corruption. The Lokpal and Lokayuktas Act, 2013, emerged as a result of this awareness, along with the government's legal obligations to implement the terms of the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC).

The procedure used to investigate and prosecute corrupt public officials

- The Central Vigilance Commission (CVC), the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), and the state Anti-Corruption Bureau are the three primary bodies involved in enquiring, investigating, and prosecuting corruption matters. The Directorate of Enforcement and the Financial Intelligence Unit, both of which fall under the Ministry of Finance, look into and prosecute cases involving money laundering by public employees.

- Under the Prevention of Corruption Act of 1988 and the Indian Penal Code of 1860, the CBI and state ACBs investigate charges of corruption. The CBI investigates cases inside the federal government and Union Territories, whilst state ACBs investigate crimes within the states. Cases can be referred to the CBI by states.

- The CVC is a statutory agency that oversees corruption investigations in government agencies. It is in charge of the CBI. The CVC has the authority to recommend matters to the Central Vigilance Officer (CVO) in each department or to the CBI. The CVC or CVO advises disciplinary action against a public worker, but the decision to take such action against a civil servant remains with the department authorities.

- An investigative agency may commence a prosecution only with the prior approval of the national or state government. Prosecutors chosen by the government handle the prosecution process in the courts.

- Under the Prevention of Corruption Act of 1988, all matters are heard by Special Judges chosen by the national or state governments.

Amendments to the Act

The Prevention of Corruption Act of 1988 was recently updated because no further improvements were made to the Act, resulting in its limited success. With this Act’s limited success, a new Act was required. As a result, The Prevention of Corruption Act, 2018 went into effect (the “Amendment Act”). The majority of the revisions are targeted at tightening up the Act’s current provisions and broadening the scope of the offences.

The significant changes to the Act are as follows:

- The word “Prescribed” has been adopted to refer to rules that the Central Government may create under the Act. As a result, we predict the following rules: Rules requiring organisations and businesses to develop internal policies and procedures to prevent their personnel from giving undue benefit to public officials and rules governing the prosecution of a public servant under the Act.

- “Undue advantage” after this amendment is defined as any reward other than legal payment. Similarly, the term “gratification” has been defined to embrace all types of monetary gratification other than economic gratification.

- The phrase “Legal remuneration” under this amended Act has been defined to cover all pay that a public worker is authorised by the relevant body to receive.

- Under Section 4(4), the courts no longer have to finish trials for Act-related offences within two years, failing which the judges must record the necessity for a time extension. A trial can now be prolonged for six months at a time up to a maximum of four years.

- The amended Section 8 lays out the consequences for anybody who aids in the payment of a bribe or attempts to engage in corruption alongside a public official. The Amendment Act exempts actions taken under duress as long as the person who was forced to take them files a complaint with the police or an investigative agency within seven days after paying a bribe.

- For business organisations, Section 9 now clearly addresses business organisations and the people connected to them. The phrase “persons affiliated with the commercial organisation” is broad enough to cover workers and suppliers, while the word “commercial organisation” is defined to include all types of corporate organisations.

- For the penalty section under this Act, provides that where the commercial organisation’s directors, officers in default, or a person with power over the organisation has consented to the corrupt act breaking the Act’s requirements, Section 10 now sets specific periods for imprisonment and a fine.

- When Sections 10 and 9 are amended together, it may be helpful to keep in mind that the amended Act appears to punish both commercial organisations for violating the Act by levying a fine and the officers in charge of such commercial organisations under Section 10 by subjecting them to criminal liability.

- For provisions related to public servant corruption, it appears that the Amendment Act has reduced the circumstances in which a public employee may be charged with suspected criminal misbehaviour. Only the misappropriation of property and unjust enrichment are included as reasons for misconduct in the modified Section 13 of the Act, which is assessed by disproportionate assets. In the past, Section 13 included broad propensities to engage in corrupt behaviour or seek bribes as grounds for criminal wrongdoing.

- The Amendment Act seems to make it more challenging to bring charges against government personnel. According to the change made under Section 19, to prosecute a public employee under Sections 7, 11, 13, and 15 of the Act, a sanction must first be acquired from a body that has the power to fire them. Second, an authorization request must be made by the investigating authority such as a police officer or else other complaints must be satisfied before the court may declare an offence to have occurred.

Act-related constitutional provisions

- The codified laws additionally provide statutory and legal provisions against corruption. The provision of Writ Jurisdiction is also included in the supreme law, namely the Indian Constitution. The office of the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) is established to control money and economic offences; in addition, there are authorities at the Central and state levels such as the Central Vigilance Commission, the Committee on Parliament Accounts, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), and the Anti-Corruption Bureau of State (ACBS).

- The Supreme Court is the Constitution’s custodian. The Constitution has enabled the Supreme Court to protect the basic rights entrenched in Part III of the Constitution. Fundamental rights are rights against the overwhelming powers of the state. The state is defined under Article 12 of the Constitution. The following Writs are provided by Articles 32 and 226 of the Indian Constitution, as well as the opportunity of Public Interest Litigation (PIL) is available.

- Writ of Habeas Corpus;

- Writ of Mandamus;

- Writ of Prohibition;

- Writ of Certiorari; and

- Writ of Quo-Warranto

- All of these writs have their own influence and authority in various domains, and they are nothing more than powers in the hands of the judiciary to restrict administrative discretion. The preamble of the Indian Constitution guarantees the residents of India the right to justice. The Constitution established a federal government, which consists of a Central government and state governments at the state level. Crime is included as a state issue, although law and order are listed concurrently. A number of measures in the Constitution have been enacted to combat corruption in society. Article 311 of the Indian Constitution and the judicial reform process seek to remove corruption from society.

Judicial pronouncements

Parkash Singh Badal And Anr vs State Of Punjab And Ors, (2006)

The Supreme Court ruled in the case of Parkash Singh Badal And Anr vs State Of Punjab And Ors, (2006) that if a public servant received compensation for persuading another public servant to perform or refrain from performing any official act, he would be subject to the provisions of Sections 8 and 9 of the Prevention of Corruption Act. In the same case, the Supreme Court determined that satisfaction might be of any form for Sections 8 and 9, indicating that the scope of their applicability was broad. In this instance, the Court was investigating the relationship between offences under Sections 8 and 9 and Section 13(1)(d) on the one hand.

Subash Parbat Sonvane vs State of Gujarat (2002)

Similar to Section 7, Section 13(1)(d) has been the focus of extensive litigation. The Supreme Court in the case of Subash Parbat Sonvane vs State of Gujarat (2002) held that to be found guilty under Section 13(1)(d), there must be proof that the subject of the investigation, i.e the person under investigation, obtained something valuable or financially advantageous for himself or another person through dishonest or illegal means, by abusing his position as a public servant, or by obtaining something valuable or financially advantageous for another person without any consideration of the public interest.

Bhupinder Singh Sikka vs CBI (2011)

The Delhi High Court in the case of Bhupinder Singh Sikka vs CBI, (2011) found that an employee of an insurance company established by an Act of Parliament was inherently a public servant and that no evidence was necessary in this regard. The Supreme Court’s wide definitions may result in unpredictability and confusion in the law.

Habibulla Khan vs State of Orissa (1995)

It was decided in this case, Habibulla Khan vs State of Orissa,(1995) that, while an M.L.A. falls under the definition of a “public servant,” he is not the type of “public servant” for whom the prior sanction is necessary for prosecution. This paradox was further resolved by a five-judge bench of the Hon’ble Supreme Court in P.V. Narasimha Rao vs State (C.B.I.), 1998, which stated that a Member of Parliament holds an office and is required or accredited to execute responsibilities like public obligations by such office.

As a result, even if no authority may issue approval for his prosecution under Section 19(1) of the Act, an MP would fall within the purview of subparagraph (viii) of clause (c) of Section 2 of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988. It was also determined that sanction is not required for the court to take notice of the offences and that the prosecuting agency must obtain permission from the Chairman of the Rajya Sabha or the Speaker of the Lok Sabha, as the case may be, before submitting the charge sheet.

Amrit Lal vs State of Punjab (2016)

Bribery was addressed in Section 7 of the Prevention of Corruption Act of 1988. The complainant’s evidence about the bribe money demand was not validated due to a lack of verification. The amount of money asked as a bribe was challenged in the complaint. Furthermore, two witnesses who testified in front of whom the contaminated money was seized were not interrogated and were unnecessarily released. The Punjab-Haryana High Court, in this case, Amrit Lal vs State of Punjab, (2016) determined that the appellant was entitled to the benefit of the doubt and therefore acquitted of the allegation.

Vasant Rao Guhe vs State of M.P. (2017)

The Supreme Court held in this case of Vasant Rao Guhe vs State of M.P., (2017), that a public official accused of criminal misconduct cannot be expected to explain the absence of evidence to support the claim that he had property or money that was out of proportion to his known sources of income. The bench ruled that the prosecution must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the public servant, either directly or indirectly through another person, had at any point during his employment had pecuniary resources or property that was out of proportion to his known sources of income. If the prosecution fails to prove this burden, the prosecution will only be able to prove criminal misconduct.

Conclusion

Thus, the evil of corruption has been endangering the evolution of humanity and civilization. Regardless of the period, evil has persisted due to the hungry character of humans. Humans are drawn to this evil because of the material benefits they gain from engaging in immoral acts. This Act may be useful in developing an efficient system to combat the evil of corruption. As a result, the Prevention of Corruption Act of 1988 is an important statute to combat corruption. However, an Act alone will always lose this battle against corruption; it is also the performance of our lawmakers that will give us an advantage in controlling this menace.

Be aware that nothing in the universe could be perfect, and that this Act is subject to the same rule. Further, if needed, effective amendments have to be passed, but the investigating agencies’ effectiveness and efficiency are also crucial in this respect. With the most recent revisions, it is now facing blisters from legal heavyweights, but this should be avoided, and lawmakers should work to find the gap in the law and close it as completely as possible.

|

43 videos|394 docs

|

FAQs on Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 - Law Optional Notes for UPSC

| 1. What is the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988? |  |

| 2. What are the distinctive features of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988? |  |

| 3. What are the important provisions of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988? |  |

| 4. How is investigation conducted under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988? |  |

| 5. What are the amendments made to the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988? |  |

|

Explore Courses for UPSC exam

|

|