Molluscs: Locomotion | Zoology Optional Notes for UPSC PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Locomotion in Mollusca |

|

| Foot as a Creeping and Crawling Organ |

|

| Foot as a burrowing Organ |

|

| Foot as a Leaping Organ |

|

| Foot as a Swimming Organ |

|

Locomotion in Mollusca

The foot is the primary locomotor organ in Mollusca and exhibits various modifications to serve the diverse locomotion needs of different groups of mollusks. Here are some of the key modifications and adaptations of the foot in various mollusk groups for different modes of locomotion:

- Crawling (Creeping): In its simplest form, the foot is a flat ventral sole that allows for secure attachment and slow progression of the body by crawling. Cilia and mucus cells may be present on the foot to aid in locomotion.

- Burrowing: Some mollusks, like burrowing bivalves (e.g., clams and razor clams), have evolved specialized feet that are adapted for digging into sediment or substrate. These modified feet are used to create burrows for protection and feeding.

- Leaping (Jumping): Some gastropods, such as land snails, have developed a muscular foot that is capable of contracting rapidly. This allows them to leap or jump over short distances, typically as a response to threats or when searching for food.

- Swimming: Some mollusks, like cephalopods (e.g., squids and octopuses), have evolved a unique form of locomotion. They use jet propulsion for swimming by expelling water forcefully through a siphon or funnel. The muscular foot helps in creating the jet of water that propels the animal forward.

- Lateral Flattening: In certain species, such as flatworm-like solenogastres and aplacophorans, the foot is laterally flattened to provide stability and support while creeping or burrowing.

- Pedicellariae: Some sea stars (echinoderms) have specialized appendages called pedicellariae, which function as tiny "feet" equipped with pincers. These pedicellariae help in locomotion by gripping onto surfaces or capturing prey.

- Attachment Discs: In certain mollusks, like chitons, the foot may have suction-like attachment discs or glands that enable the animal to cling tightly to rocky surfaces in intertidal zones.

- Swimming Appendages: Some pelagic snails, like pteropods and heteropods, have developed modified foot structures that serve as swimming appendages to help them navigate through the water column.

These various adaptations of the foot are closely related to the environment and the specific modes of living of mollusks. Mollusks have evolved a wide range of locomotor strategies to suit their ecological niches, whether it involves crawling on the ocean floor, burrowing in sediment, swimming in open water, or moving on land. The diversity of foot structures and locomotion mechanisms within the phylum Mollusca reflects the adaptability and versatility of these organisms in different habitats.

Foot as a Creeping and Crawling Organ

The foot in mollusks is a highly versatile organ that has undergone various modifications to facilitate creeping and crawling movements. The type of locomotion varies among different groups of mollusks, and their foot structures have evolved to suit their specific needs. Here are some examples of foot adaptations for creeping and crawling in different mollusk groups:

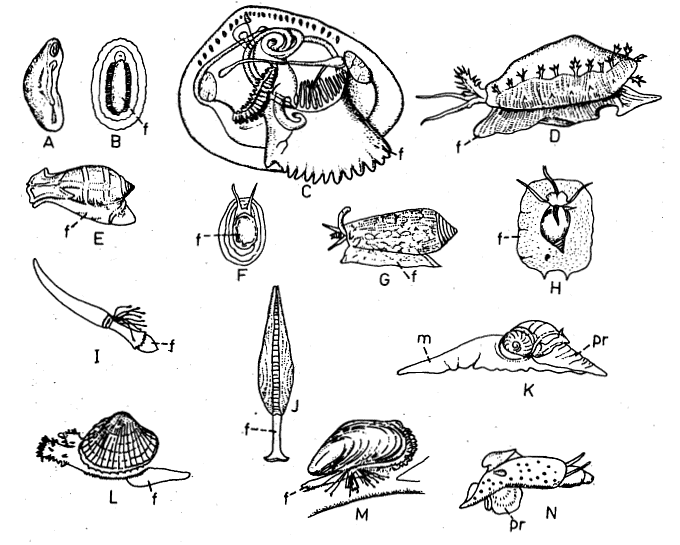

Aplacophorans (Proneomenia): Aplacophorans have a simple foot with a ventral groove and ciliated ridges, allowing them to glide on the ventral surface of the foot. This type of locomotion is common in small aquatic gastropods.

Polyplacophora (Chiton): Chitons have a broad and flat foot that helps them to crawl efficiently over rocky surfaces. The foot's shape allows it to make good contact with the substrate for secure crawling.

Bivalves (Unio, Anodonta, Nucula): Bivalves may have triangular or laterally compressed feet, which are used for burrowing into sediment or for slow creeping along the substrate. These foot shapes vary among different bivalve species.

Gastropods (Cowries, Actaeon, Patella, Triton, Conus, Bullia): Gastropods exhibit a wide range of foot shapes to support their crawling movements. For example, some gastropods have a large, flat foot lobe that provides stability during crawling (e.g., cowries). Others, like Conus, have a long, backwardly bent siphon, and some, like Bullia, have a foot that encircles their entire body, allowing for efficient crawling.

These various foot adaptations highlight the diversity of crawling and creeping mechanisms within the mollusk phylum. Mollusks have evolved different foot shapes and locomotion strategies to navigate their specific environments, whether it involves moving over rocky substrates, burrowing into sediments, or creeping along the seafloor. The foot's interaction with muscular contractions, the pressure of the coelomic fluid, and the secretion of mucus on the pedal surface are essential components of these locomotion mechanisms.

Foot as a burrowing Organ

Mollusks have developed a wide range of foot modifications to support their specific locomotion needs, including burrowing. Different mollusk groups have evolved specialized foot structures and behaviors to facilitate burrowing in various environments. Here are some examples of burrowing adaptations in different mollusk species:

- Scaphopoda (Dentalium): Scaphopods typically have a burrowing habit and possess a conical and protrusible foot that is trilobed at its distal end. This specialized foot allows them to thrust into the sand when burrowing. The lobes can be erected to increase anchorage and stability during the burrowing process.

- Bivalves (Pholas, Teredo): Some bivalves, like Pholas, are known for their burrowing behavior. They have a blunt, short foot that is used for boring into rocks. These bivalves attach to the substrate using the sucker-like surface of the foot. The muscles of the foot produce various movements that generate the necessary cutting force. The sharp cutting edges on the anterior ends of the valves aid in the burrowing process. Shipworms, like Teredo, also bore into wood using a similar mechanism.

- Bivalves (Yoldia): In Yoldia, the two sides of the foot can be folded to form a wedge shape, which assists in easy burrowing into the sand or mud. This wedge-shaped foot allows the mollusk to penetrate the substrate efficiently.

- Burrowing Gastropods (Sigaretus): Some burrowing gastropods, such as Sigaretus, have specialized anterior portions of the foot called protopodium. This protopodium is wedge-shaped and is used to aid in the burrowing process. It allows the gastropod to penetrate and move through sediments more effectively.

The burrowing action in mollusks typically involves thrusting the blade of the foot into sand, mud, wood, or other substrates. The distal part of the foot can be dilated using protractor muscles, which, when combined with blood pressure, acts as an anchor. Contraction of the retractor muscles then pulls the animal downward, assisting in the burrowing process.

These diverse adaptations in foot structure and behavior reflect the varied environments and substrates in which mollusks burrow. Whether they are burrowing into sediments, rocks, or wood, mollusks have evolved specific mechanisms to suit their burrowing needs.

The foot in mollusks serves various locomotor functions, including leaping and swimming. Different groups of mollusks have developed specialized adaptations for leaping and swimming, as described below:

Foot as a Leaping Organ

- Bivalves (Trigonia, Cardium): Many bivalves use their foot as a leaping organ. The anteroposteriorly compressed foot of Trigonia forms a keel, and in Cardium, the foot is bent upon itself. These modifications allow them to leap when the foot is rapidly extended from the folded position. This leaping behavior is typically associated with changes in habitat from soft sandy or muddy substrates to hard rocky and exposed ones.

- Bivalves (Mytilus): In Mytilus, byssus threads, formed by the secretion of glands associated with the foot, anchor the animal to rocks. The foot is adapted for byssus thread production, and this attachment mechanism allows them to remain stationary in their habitat.

- Bivalves (Pecten): In the scallop Pecten, the foot is atrophied, and the mollusk accomplishes movement in a unique way by flapping its thin, broad valves. This flapping motion helps the scallop move through the water.

Foot as a Swimming Organ

- Swimming Gastropods: Swimming is common among some gastropods. They exhibit a wide variety of foot modifications for swimming. Pelagic gastropods, like Carinaria, have a mesopodium, a thin muscular fin in the middle portion of the foot, which helps produce undulating movements. Nudibranchs have flattened bodies with thin lateral projections of the foot called parapodia, which act like fins. They can swim by flapping these fan-shaped parapodia.

- Pteropods (Sea-butterflies): Pteropods are planktonic mollusks with wing-like parapodia. These structures, found in species like Oxygyrus and Clione, allow them to swim in the open ocean.

- Cephalopods: Cephalopods, such as octopuses, Loligo, Sepia, and Amphitretus, have highly modified feet and mantle cavities. They are efficient swimmers and use jet propulsion to move through the water. Cephalopods discharge water from the mantle cavity through the funnel with great force, propelling themselves. They also have arms and tentacles around the head, which are used for capturing prey. While octopuses crawl using their powerful arms, they are generally poor swimmers.

In sessile mollusks and those with reduced mobility, the foot may be reduced or feeble. In some gastropods and bivalves that lead a relatively sessile lifestyle, the foot is weak or reduced. Sessile forms like worm shells (vermetidae and Siliquariidae), which have tube-like shells, also possess a reduced foot. Additionally, parasitic mesogastropods and bivalves, like Entovalva, have reduced foot structures as they primarily occur as endoparasites of echinoderms.

|

181 videos|346 docs

|

|

Explore Courses for UPSC exam

|

|