Batteries and Fuel Cells | Chemistry Optional Notes for UPSC PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Introduction |

|

| Batteries |

|

| Leclanché Dry Cell |

|

| Button Batteries |

|

| Lithium–Iodine Battery |

|

| Nickel–Cadmium (NiCad) Battery |

|

| Lead–Acid (Lead Storage) Battery |

|

| Fuel Cells |

|

| Summary |

|

Introduction

Because galvanic cells can be self-contained and portable, they can be used as batteries and fuel cells. A battery (storage cell) is a galvanic cell (or a series of galvanic cells) that contains all the reactants needed to produce electricity. In contrast, a fuel cell is a galvanic cell that requires a constant external supply of one or more reactants to generate electricity. In this section, we describe the chemistry behind some of the more common types of batteries and fuel cells.

Batteries

- There are two basic kinds of batteries: disposable, or primary, batteries, in which the electrode reactions are effectively irreversible and which cannot be recharged; and rechargeable, or secondary, batteries, which form an insoluble product that adheres to the electrodes. These batteries can be recharged by applying an electrical potential in the reverse direction.

- The recharging process temporarily converts a rechargeable battery from a galvanic cell to an electrolytic cell. Batteries are cleverly engineered devices that are based on the same fundamental laws as galvanic cells. The major difference between batteries and the galvanic cells we have previously described is that commercial batteries use solids or pastes rather than solutions as reactants to maximize the electrical output per unit mass.

- The use of highly concentrated or solid reactants has another beneficial effect: the concentrations of the reactants and the products do not change greatly as the battery is discharged; consequently, the output voltage remains remarkably constant during the discharge process. This behavior is in contrast to that of the Zn/Cu cell, whose output decreases logarithmically as the reaction proceeds (Figure 20.7.1 ). When a battery consists of more than one galvanic cell, the cells are usually connected in series—that is, with the positive (+) terminal of one cell connected to the negative (−) terminal of the next, and so forth. The overall voltage of the battery is therefore the sum of the voltages of the individual cells.

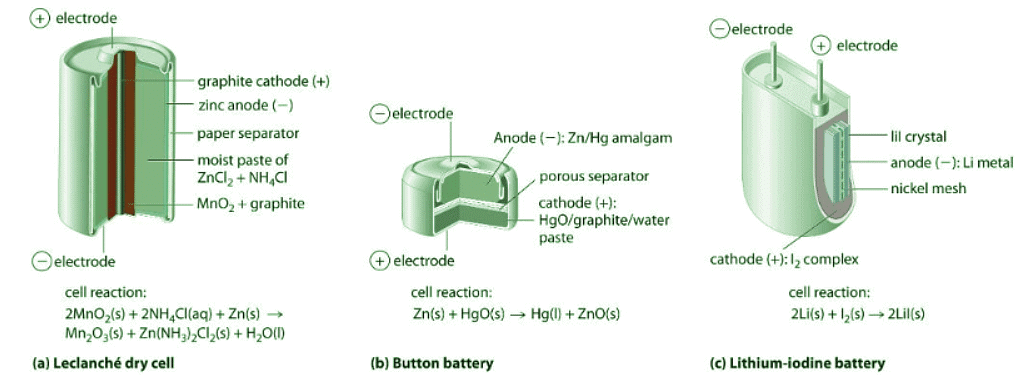

Figure 20.7.1: Three Kinds of Primary (Nonrechargeable) Batteries. (a) A Leclanché dry cell is actually a “wet cell,” in which the electrolyte is an acidic water-based paste containing MnO2, NH4Cl, ZnCl2, graphite, and starch. Though inexpensive to manufacture, the cell is not very efficient in producing electrical energy and has a limited shelf life. (b) In a button battery, the anode is a zinc–mercury amalgam, and the cathode can be either HgO (shown here) or Ag2O as the oxidant. Button batteries are reliable and have a high output-to-mass ratio, which allows them to be used in applications such as calculators and watches, where their small size is crucial. (c) A lithium–iodine battery consists of two cells separated by a metallic nickel mesh that collects charge from the anodes. The anode is lithium metal, and the cathode is a solid complex of I2. The electrolyte is a layer of solid LiI that allows Li+ ions to diffuse from the cathode to the anode. Although this type of battery produces only a relatively small current, it is highly reliable and long-lived.

Figure 20.7.1: Three Kinds of Primary (Nonrechargeable) Batteries. (a) A Leclanché dry cell is actually a “wet cell,” in which the electrolyte is an acidic water-based paste containing MnO2, NH4Cl, ZnCl2, graphite, and starch. Though inexpensive to manufacture, the cell is not very efficient in producing electrical energy and has a limited shelf life. (b) In a button battery, the anode is a zinc–mercury amalgam, and the cathode can be either HgO (shown here) or Ag2O as the oxidant. Button batteries are reliable and have a high output-to-mass ratio, which allows them to be used in applications such as calculators and watches, where their small size is crucial. (c) A lithium–iodine battery consists of two cells separated by a metallic nickel mesh that collects charge from the anodes. The anode is lithium metal, and the cathode is a solid complex of I2. The electrolyte is a layer of solid LiI that allows Li+ ions to diffuse from the cathode to the anode. Although this type of battery produces only a relatively small current, it is highly reliable and long-lived.

The major difference between batteries and the galvanic cells is that commercial typically batteries use solids or pastes rather than solutions as reactants to maximize the electrical output per unit mass. An obvious exception is the standard car battery which used solution phase chemistry.

Leclanché Dry Cell

The dry cell, by far the most common type of battery, is used in flashlights, electronic devices such as the Walkman and Game Boy, and many other devices. Although the dry cell was patented in 1866 by the French chemist Georges Leclanché and more than 5 billion such cells are sold every year, the details of its electrode chemistry are still not completely understood. In spite of its name, the Leclanché dry cell is actually a “wet cell”: the electrolyte is an acidic water-based paste containing MnO2, NH4Cl, ZnCl2, graphite, and starch (part (a) in Figure 20.7.1 ). The half-reactions at the anode and the cathode can be summarized as follows:

- cathode (reduction):

- anode (oxidation):

The Zn2+ ions formed by the oxidation of Zn(s) at the anode react with NH3 formed at the cathode and Cl− ions present in solution, so the overall cell reaction is as follows:

- overall reaction:

The dry cell produces about 1.55 V and is inexpensive to manufacture. It is not, however, very efficient in producing electrical energy because only the relatively small fraction of the MnO2 that is near the cathode is actually reduced and only a small fraction of the zinc cathode is actually consumed as the cell discharges. In addition, dry cells have a limited shelf life because the Zn anode reacts spontaneously with NH4Cl in the electrolyte, causing the case to corrode and allowing the contents to leak out.

The alkaline battery is essentially a Leclanché cell adapted to operate under alkaline, or basic, conditions. The half-reactions that occur in an alkaline battery are as follows:

- cathode (reduction):

- anode (oxidation):

- overall reaction:

This battery also produces about 1.5 V, but it has a longer shelf life and more constant output voltage as the cell is discharged than the Leclanché dry cell. Although the alkaline battery is more expensive to produce than the Leclanché dry cell, the improved performance makes this battery more cost-effective.

Button Batteries

Although some of the small button batteries used to power watches, calculators, and cameras are miniature alkaline cells, most are based on a completely different chemistry. In these "button" batteries, the anode is a zinc–mercury amalgam rather than pure zinc, and the cathode uses either HgO or Ag2O as the oxidant rather than MnO2 in Figure 20.7.1b ). The cathode, anode and overall reactions and cell output for these two types of button batteries are as follows (two half-reactions occur at the anode, but the overall oxidation half-reaction is shown):

The cathode, anode and overall reactions and cell output for these two types of button batteries are as follows (two half-reactions occur at the anode, but the overall oxidation half-reaction is shown):

- cathode (mercury battery):

- Anode (mercury battery):

- overall reaction (mercury battery):

with Ecell = 1.35V. - cathode reaction (silver battery):

- anode (silver battery):

- Overall reaction (silver battery):

with Ecell = 1.6V.

The major advantages of the mercury and silver cells are their reliability and their high output-to-mass ratio. These factors make them ideal for applications where small size is crucial, as in cameras and hearing aids. The disadvantages are the expense and the environmental problems caused by the disposal of heavy metals, such as Hg and Ag.

Lithium–Iodine Battery

None of the batteries described above is actually “dry.” They all contain small amounts of liquid water, which adds significant mass and causes potential corrosion problems. Consequently, substantial effort has been expended to develop water-free batteries. One of the few commercially successful water-free batteries is the lithium–iodine battery. The anode is lithium metal, and the cathode is a solid complex of I2. Separating them is a layer of solid LiI, which acts as the electrolyte by allowing the diffusion of Li+ ions. The electrode reactions are as follows:

- cathode (reduction):

- anode (oxidation):

- overall:

with Ecell = 3.5V

As shown in part (c) in Figure 20.7.1, a typical lithium–iodine battery consists of two cells separated by a nickel metal mesh that collects charge from the anode. Because of the high internal resistance caused by the solid electrolyte, only a low current can be drawn. Nonetheless, such batteries have proven to be long-lived (up to 10 yr) and reliable. They are therefore used in applications where frequent replacement is difficult or undesirable, such as in cardiac pacemakers and other medical implants and in computers for memory protection. These batteries are also used in security transmitters and smoke alarms. Other batteries based on lithium anodes and solid electrolytes are under development, using TiS2, for example, for the cathode.

Dry cells, button batteries, and lithium–iodine batteries are disposable and cannot be recharged once they are discharged. Rechargeable batteries, in contrast, offer significant economic and environmental advantages because they can be recharged and discharged numerous times. As a result, manufacturing and disposal costs drop dramatically for a given number of hours of battery usage. Two common rechargeable batteries are the nickel–cadmium battery and the lead–acid battery, which we describe next.

Nickel–Cadmium (NiCad) Battery

The nickel–cadmium, or NiCad, battery is used in small electrical appliances and devices like drills, portable vacuum cleaners, and AM/FM digital tuners. It is a water-based cell with a cadmium anode and a highly oxidized nickel cathode that is usually described as the nickel(III) oxo-hydroxide, NiO(OH). As shown in Figure 20.7.2, the design maximizes the surface area of the electrodes and minimizes the distance between them, which decreases internal resistance and makes a rather high discharge current possible. Figure 20.7.2: The Nickel–Cadmium (NiCad) Battery, a Rechargeable Battery. NiCad batteries contain a cadmium anode and a highly oxidized nickel cathode. This design maximizes the surface area of the electrodes and minimizes the distance between them, which gives the battery both a high discharge current and a high capacity.

Figure 20.7.2: The Nickel–Cadmium (NiCad) Battery, a Rechargeable Battery. NiCad batteries contain a cadmium anode and a highly oxidized nickel cathode. This design maximizes the surface area of the electrodes and minimizes the distance between them, which gives the battery both a high discharge current and a high capacity.

The electrode reactions during the discharge of a NiCad battery are as follows:

- cathode (reduction):

- anode (oxidation):

- overall:

Because the products of the discharge half-reactions are solids that adhere to the electrodes [Cd(OH)2 and 2Ni(OH)2], the overall reaction is readily reversed when the cell is recharged. Although NiCad cells are lightweight, rechargeable, and high capacity, they have certain disadvantages. For example, they tend to lose capacity quickly if not allowed to discharge fully before recharging, they do not store well for long periods when fully charged, and they present significant environmental and disposal problems because of the toxicity of cadmium.

A variation on the NiCad battery is the nickel–metal hydride battery (NiMH) used in hybrid automobiles, wireless communication devices, and mobile computing.

The overall chemical equation for this type of battery is as follows:

\[NiO(OH)_{(s)} + MH \rightarrow Ni(OH)_{2(s)} + M_{(s)} \label{Eq16} \]

The NiMH battery has a 30%–40% improvement in capacity over the NiCad battery; it is more environmentally friendly so storage, transportation, and disposal are not subject to environmental control; and it is not as sensitive to recharging memory. It is, however, subject to a 50% greater self-discharge rate, a limited service life, and higher maintenance, and it is more expensive than the NiCad battery.

Directive 2006/66/EC of the European Union prohibits the placing on the market of portable batteries that contain more than 0.002% of cadmium by weight. The aim of this directive was to improve "the environmental performance of batteries and accumulators"

Lead–Acid (Lead Storage) Battery

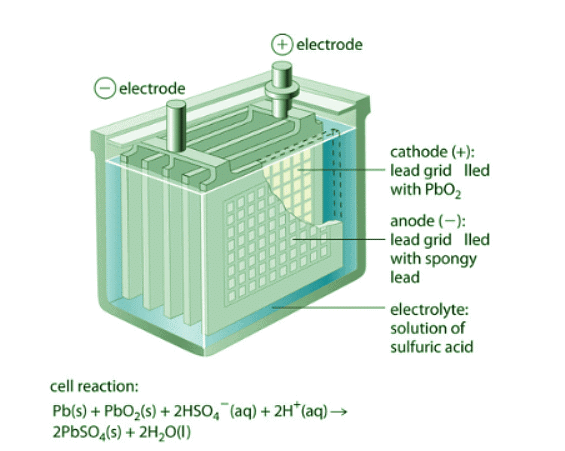

The lead–acid battery is used to provide the starting power in virtually every automobile and marine engine on the market. Marine and car batteries typically consist of multiple cells connected in series. The total voltage generated by the battery is the potential per cell (E°cell) times the number of cells.

Figure 20.7.3: One Cell of a Lead–Acid Battery. The anodes in each cell of a rechargeable battery are plates or grids of lead containing spongy lead metal, while the cathodes are similar grids containing powdered lead dioxide (PbO2). The electrolyte is an aqueous solution of sulfuric acid. The value of E° for such a cell is about 2 V. Connecting three such cells in series produces a 6 V battery, whereas a typical 12 V car battery contains six cells in series. When treated properly, this type of high-capacity battery can be discharged and recharged many times over.

As shown in Figure 20.7.3, the anode of each cell in a lead storage battery is a plate or grid of spongy lead metal, and the cathode is a similar grid containing powdered lead dioxide ( PbO2). The electrolyte is usually an approximately 37% solution (by mass) of sulfuric acid in water, with a density of 1.28 g/mL (about 4.5 M H2SO4). Because the redox active species are solids, there is no need to separate the electrodes.

The electrode reactions in each cell during discharge are as follows:

- cathode (reduction):

\[PbO_{2(s)} + HSO^−_{4(aq)} + 3H^+_{(aq)} + 2e^− \rightarrow PbSO_{4(s)} + 2H_2O_{(l)} \label{Eq17} \] with

E∘cathode = 1.685V - anode (oxidation):

with E∘anode = −0.356V - overall:

and E∘cell = 2.041V

and E∘cell = 2.041V

As the cell is discharged, a powder of PbSO4 forms on the electrodes. Moreover, sulfuric acid is consumed and water is produced, decreasing the density of the electrolyte and providing a convenient way of monitoring the status of a battery by simply measuring the density of the electrolyte. This is often done with the use of a hydrometer.

When an external voltage in excess of 2.04 V per cell is applied to a lead–acid battery, the electrode reactions reverse, and PbSO4 is converted back to metallic lead and PbO2. If the battery is recharged too vigorously, however, electrolysis of water can occur:

This results in the evolution of potentially explosive hydrogen gas. The gas bubbles formed in this way can dislodge some of the PbSO4 or PbO2 particles from the grids, allowing them to fall to the bottom of the cell, where they can build up and cause an internal short circuit. Thus the recharging process must be carefully monitored to optimize the life of the battery. With proper care, however, a lead–acid battery can be discharged and recharged thousands of times. In automobiles, the alternator supplies the electric current that causes the discharge reaction to reverse.

Fuel Cells

A fuel cell is a galvanic cell that requires a constant external supply of reactants because the products of the reaction are continuously removed. Unlike a battery, it does not store chemical or electrical energy; a fuel cell allows electrical energy to be extracted directly from a chemical reaction. In principle, this should be a more efficient process than, for example, burning the fuel to drive an internal combustion engine that turns a generator, which is typically less than 40% efficient, and in fact, the efficiency of a fuel cell is generally between 40% and 60%. Unfortunately, significant cost and reliability problems have hindered the wide-scale adoption of fuel cells. In practice, their use has been restricted to applications in which mass may be a significant cost factor, such as US manned space vehicles. Figure 20.7.4: A Hydrogen Fuel Cell Produces Electrical Energy Directly from a Chemical Reaction. Hydrogen is oxidized to protons at the anode, and the electrons are transferred through an external circuit to the cathode, where oxygen is reduced and combines with H+ to form water. A solid electrolyte allows the protons to diffuse from the anode to the cathode. Although fuel cells are an essentially pollution-free means of obtaining electrical energy, their expense and technological complexity have thus far limited their applications.

Figure 20.7.4: A Hydrogen Fuel Cell Produces Electrical Energy Directly from a Chemical Reaction. Hydrogen is oxidized to protons at the anode, and the electrons are transferred through an external circuit to the cathode, where oxygen is reduced and combines with H+ to form water. A solid electrolyte allows the protons to diffuse from the anode to the cathode. Although fuel cells are an essentially pollution-free means of obtaining electrical energy, their expense and technological complexity have thus far limited their applications.

These space vehicles use a hydrogen/oxygen fuel cell that requires a continuous input of H2(g) and O2(g), as illustrated in Figure 20.7.4.

The electrode reactions are as follows:

- cathode (reduction):

- anode (oxidation):

- overall:

The overall reaction represents an essentially pollution-free conversion of hydrogen and oxygen to water, which in space vehicles is then collected and used. Although this type of fuel cell should produce 1.23 V under standard conditions, in practice the device achieves only about 0.9 V. One of the major barriers to achieving greater efficiency is the fact that the four-electron reduction of O2(g) at the cathode is intrinsically rather slow, which limits current that can be achieved. All major automobile manufacturers have major research programs involving fuel cells: one of the most important goals is the development of a better catalyst for the reduction of O2(g).

Summary

- Commercial batteries are galvanic cells that use solids or pastes as reactants to maximize the electrical output per unit mass. A battery is a contained unit that produces electricity, whereas a fuel cell is a galvanic cell that requires a constant external supply of one or more reactants to generate electricity. One type of battery is the Leclanché dry cell, which contains an electrolyte in an acidic water-based paste.

- This battery is called an alkaline battery when adapted to operate under alkaline conditions. Button batteries have a high output-to-mass ratio; lithium–iodine batteries consist of a solid electrolyte; the nickel–cadmium (NiCad) battery is rechargeable; and the lead–acid battery, which is also rechargeable, does not require the electrodes to be in separate compartments. A fuel cell requires an external supply of reactants as the products of the reaction are continuously removed. In a fuel cell, energy is not stored; electrical energy is provided by a chemical reaction.

FAQs on Batteries and Fuel Cells - Chemistry Optional Notes for UPSC

| 1. What is a Leclanché Dry Cell? |  |

| 2. What are button batteries? |  |

| 3. How does a lithium-iodine battery work? |  |

| 4. What are the advantages of a nickel-cadmium (NiCad) battery? |  |

| 5. What is a lead-acid battery commonly used for? |  |

|

Explore Courses for UPSC exam

|

|

and E∘cell = 2.041V

and E∘cell = 2.041V