Unit 1: Meaning and Types of Markets Chapter Notes | Business Economics for CA Foundation PDF Download

Understanding the Concept of Market in Economics

In everyday language, a market refers to a place where buyers and sellers come together to exchange goods and services. However, in Economics, the term "market" has a broader meaning. It encompasses not just physical locations, but also the potential for trade between buyers and sellers, regardless of whether they are in the same place or not.

A market is essentially a collection of individuals or entities with the willingness and ability to trade. The interactions between these buyers and sellers, whether actual or potential, play a crucial role in determining the price of a product or service.

For example, when we talk about the oil market or the vegetable market, we are referring to specific instances where buyers and sellers gather to exchange these goods at a certain price. However, the concept of a market in Economics goes beyond these specific instances to include any situation where trade could potentially occur.

Free Goods vs Economic Goods

- Free Goods. These are goods that are available in abundance and do not require any payment to obtain. Examples include air and sunlight. Since these goods are not scarce, they do not have an opportunity cost associated with them.

- Economic Goods. Unlike free goods, economic goods are scarce in relation to their demand and come with an opportunity cost. These goods are exchangeable in the market and command a price because they are not available in unlimited quantities.

Price and Value

- Price. In simple terms, price refers to the amount of money needed to acquire a good or service. It represents the money-value of an item, indicating how much of it will be exchanged for a certain quantity of money.

- Value in Exchange. This concept, as explained by economist David Ricardo, refers to the power to command other commodities in exchange for a particular good. It is the basis for determining how much of other goods and services one is willing to give up to obtain a specific item.

Value in Use vs Value in Exchange

- Value in Use. This refers to the usefulness or utility of a good in satisfying human needs. It is the intrinsic value that a product holds for an individual based on its ability to meet their requirements.

- Value in Exchange. Also known as economic value, this is the amount of goods and services that one can obtain in exchange for a particular item in the market. It reflects the willingness to trade other goods and services for a specific product.

Role of Currency

- In a market economy, currency serves as a universal measure of economic value. The amount of money a person is willing to pay for a good or service indicates how much of other goods and services they are willing to forgo to acquire that item.

Importance of Exchange Value

- In Economics, the focus is primarily on exchange value rather than sentimental value. Sentimental value is subjective and reflects an exaggerated perception of a commodity's worth. For instance, if someone offers to give their friend a valuable car in exchange for a lifetime obligation, the lifetime obligation holds little significance compared to monetary considerations.

Determination of Exchange Value

- Exchange value is established in the market, where goods and services are traded between buyers and sellers. The price at which these exchanges occur reflects the value assigned to the goods and services by the market participants.

Market

A market can be informal and doesn't have to be in a specific location. For instance, second-hand cars are frequently bought and sold through newspaper ads. Similarly, second-hand items can be sold by listing them in online shops or putting up a notice in a local store. In today's high-tech world, buying and selling goods and services online has become effortless. Online shopping has transformed the business landscape by making almost everything people desire available with just a click of a button.

When studying a market economy, it's crucial to grasp how prices are determined. This process occurs within the market, which we can define as all the buyers and sellers of a particular good or service who have an impact on its price.

Elements of Market:

The key components of a market include:

(i) Buyers and sellers;

(ii) A product or service;

(iii) Negotiation for a price;

(iv) Awareness of market conditions;

(v) A single price for a product or service at a specific time.

Product Markets and Factor Markets

Markets are typically divided into product markets and factor markets.

Product Markets

- Product markets involve the sale of goods and services, where households purchase what they need from firms.

Factor Markets

- Factor markets are where firms acquire the necessary resources—land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship—to produce goods and services.

- While product markets distribute goods to consumers, factor markets allocate productive resources to producers, ensuring efficient use of these resources.

- The prices in factor markets are referred to as factor prices.

Classification of Markets

On the basis of Area- Regional Markets: Regional markets encompass a broader area, which can include several nearby cities, parts of states, or clusters of states. These markets are typically large, and the characteristics of buyers can vary significantly. For instance, the Mekhela Chador, a traditional Assamese saree, is mainly worn by women in Assam and its neighboring regions.

- National Markets:. product is said to have a national market when its demand is limited to the boundaries of a country. Government trade policies may restrict certain commodities to national markets. For example, Hindi books have a national market in India, as they may not have demand outside the country.

- International Markets:. commodity has an international market when it is traded globally. Typically, high-value and small-bulk items are in demand internationally. For instance, gold and silver are commodities with international markets. However, this classification is becoming outdated, as even highly perishable goods now have international markets.

On the basis of Time

- Very Short Period Market: This refers to a timeframe where supply is fixed and cannot be increased or decreased. Perishable commodities like vegetables, flowers, fish, eggs, fruits, and milk fall under this category. Since supply is constant, prices in the very short period depend on demand—an increase in demand raises prices and vice versa.

- Short-Period Market: The short period is slightly longer than the very short period, during which supply can be increased by employing more variable factors while keeping fixed factors and technology constant. Changes in demand affect prices in the short period, but the impact is less pronounced than in the market period.

- Long-Period Market: In the long period, all factors become variable, and the scale of production can be altered, allowing for full adjustment of supply to changes in demand. The interaction between long-run supply and demand determines the long-run equilibrium price or normal price.

- Secular or Very Long Period Market: A secular or very long-period market is one where secular movements in certain factors are observed over an extended period of time. Factors such as the size of the population, capital supply, and the supply of raw materials are considered.

On the basis of Period of Operation

Spot or Cash Market

- Spot transactions or spot markets involve the exchange of goods for money payable either immediately or within a short period of time.

- For example, grains sold in the Mandi at current prices with immediate cash payment are part of the spot market.

Forward or Future Market

- In this market, transactions involve contracts for the future delivery and payment of goods.

- For instance, purchasing foreign currency at a future rate from a bank.

On the basis of Regulation

Regulated Market

- Regulated markets involve transactions that are statutorily regulated to prevent unfair practices.

- These markets may be established for specific products or groups of products, such as stock exchanges.

Unregulated Market

- Also known as free markets, unregulated markets have no stipulations on transactions.

- Examples include weekly markets (Haat Bazaar).

On the basis of Volume of Business

Wholesale Market

- Wholesale markets involve the buying and selling of commodities in bulk or large quantities.

- Transactions typically occur between traders, i.e., Business to Business (B2B).

Retail Market

- Retail markets involve the sale of commodities in small quantities to ultimate consumers.

- This is known as Business to Consumer (B2C) transactions.

On the basis of Competition

Markets are classified based on the type of competition into:

- Perfectly Competitive Market

- Imperfectly Competitive Market

The study of these markets will be elaborated in the following sections.

Types of Market Structures

A market, from a consumer's perspective, comprises firms offering a specific product for purchase. Conversely, for a producer, a market consists of buyers interested in acquiring a particular product. When a firm understands the demand curve it faces, it can anticipate its potential revenue. By knowing its costs as well, the firm can determine the profit associated with various output levels and select the one that maximizes profit.

However, if a firm is aware of its product's costs and the market demand curve but lacks knowledge of its own demand curve (i.e., its total sales), it must address several crucial questions:

- Number of Competitors: How many other firms are selling similar products in the market?

- Market Share Sensitivity: If one firm alters its price, how will that affect its market share?

- Price Reaction: If a firm lowers its price, will other competitors follow suit?

The answers to these questions vary depending on the market circumstances. For instance:

- In a market with a single firm, that firm meets the entire market demand.

- With two large firms, they will divide the market demand between them, necessitating careful consideration of each other's reactions to decisions.

- In a scenario with many small firms (e.g., over 5,000), individual firms may be less concerned about how their decisions impact others, as each firm controls only a small market share.

Therefore, market behavior is significantly influenced by the structure of the market. While there are countless potential market structures, we will focus on a few theoretical types that represent a large portion of real-world cases:

- Perfect Competition: Characterized by numerous sellers offering identical products to many buyers.

- Monopolistic Competition: Similar to perfect competition, but with many sellers offering differentiated products to buyers, such as various shampoo brands.

- Monopoly: Involves a single seller providing a highly differentiated product to many buyers, with no close substitutes. An example is the Indian Railways.

- Oligopoly: Features a few sellers offering competing products to many buyers, such as in the telecom industry.

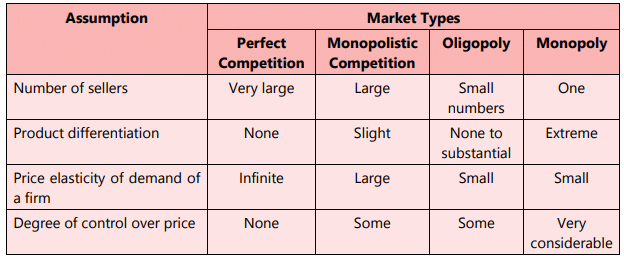

The table below summarizes the key distinguishing characteristics of these four major market forms.

Distinguishing Features of Major Types of Markets

Before diving into the details of each market form, it's important to understand the concepts of total, average, and marginal revenue, as well as the behavioral principles that apply across all market conditions.

Concepts of Total Revenue, Average Revenue, and Marginal Revenue

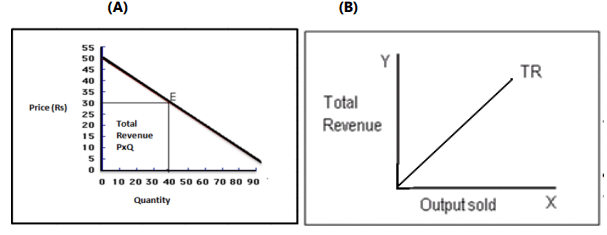

Total Revenue (TR) refers to the total amount of money a firm earns from selling a certain quantity of goods at a specific price. It's calculated using the formula: TR = P x Q, where P is the price per unit and Q is the quantity sold.

Average Revenue (AR) is the revenue earned per unit of output, which is essentially the price of one unit since price is always per unit. This is why the average revenue curve is also the firm's demand curve. It can be expressed as: AR = TR/Q or simply AR = P. For example, if a firm makes a total revenue of ₹1,000 from selling 100 units, the average revenue would be ₹10 per unit.

Marginal Revenue (MR) is the additional revenue generated from selling one more unit of a commodity. It is calculated as the change in total revenue from selling an additional unit. For instance, if total revenue increases from ₹1,000 to ₹1,200 when selling 101 units, the marginal revenue is ₹200. Mathematically, MR = Δ TR / Δ Q, where Δ represents a small change. Specifically, MRn = TRn - TRn-1, comparing total revenue at n units and (n - 1) units.

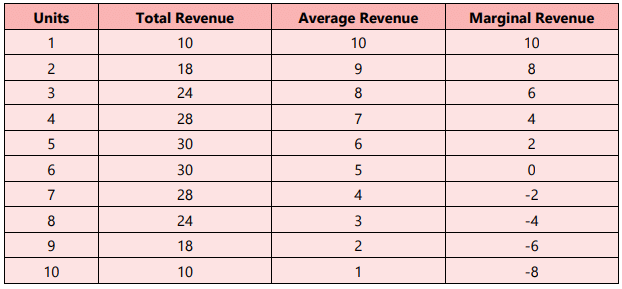

To illustrate these concepts, consider a scenario with different quantities of a commodity sold, along with the corresponding total revenue, average revenue, and marginal revenue.

Total Revenue, Average Revenue and Marginal Revenue

Total revenue is at its peak when 5 units of X are sold. It remains constant for one more unit before starting to decline. Average revenue consistently decreases, indicating an inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded. This reflects the demand function of X for the firm. Marginal revenue also continues to fall, becoming negative after reaching zero. It's important to note that total revenue at any specific level of output is the cumulative sum of marginal revenues up to that level of output.

Total revenue is at its peak when 5 units of X are sold. It remains constant for one more unit before starting to decline. Average revenue consistently decreases, indicating an inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded. This reflects the demand function of X for the firm. Marginal revenue also continues to fall, becoming negative after reaching zero. It's important to note that total revenue at any specific level of output is the cumulative sum of marginal revenues up to that level of output.

- The equation for total revenue (TR) is represented as: TR = ∑MR.

- A key question arises: why is the marginal revenue from the third unit (which is 6) not the same as the price of 8 at which this third unit is sold?

- The reason is that when the price is lowered to sell an additional unit, the two units that could have been sold for 9 earlier must now be sold at the reduced price of 8 each.

- This results in a total loss of 2 on the previous two units because of the price decrease.

- Therefore, whenever the average revenue (or price) drops, the marginal revenue will always be less than the current price.

- In cases where the average revenue (or price) remains constant, the marginal revenue will equal the average revenue (or uniform price).

- If we let TR stand for total revenue and q represent output, we can express marginal revenue (MR) as: MR = dTR/dQ.

- Here, dTR/dQ shows the slope of the total revenue curve.

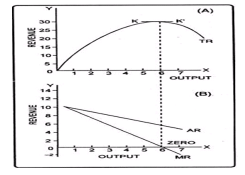

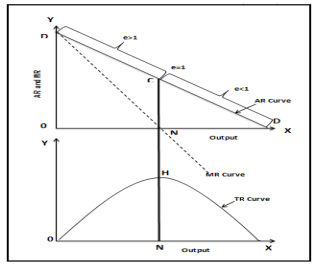

- When a firm's demand curve slopes downward normally, there exists a clear connection between average revenue, marginal revenue, and total revenue.

- This relationship can be illustrated with a figure that displays the total revenue (TR), average revenue (AR), and marginal revenue (MR) curves.

- The average revenue curve illustrates a downward slope, indicating an inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded.

- The marginal revenue curve lies beneath the average revenue curve, demonstrating that marginal revenue decreases more quickly than average revenue.

- Total revenue rises as long as marginal revenue is positive and starts to decline (showing a negative slope) when marginal revenue becomes negative.

- Initially, the total revenue curve increases at a decreasing rate due to diminishing marginal revenue, reaches a peak, and then begins to fall.

- When marginal revenue reaches zero, the total revenue is at its maximum, and the slope of the TR curve is zero.

- In all types of imperfect competition, the average revenue curve for a single firm slopes downwards. This happens because when a firm raises the price of its product, the quantity that consumers are willing to buy goes down, and if the firm lowers the price, the quantity demanded goes up.

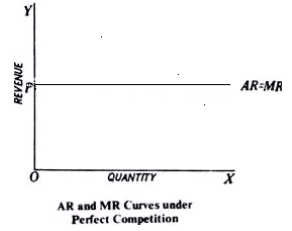

- In contrast, under perfect competition, firms are considered price takers. This means they cannot set their own prices and must accept the market price. Because of this, the average revenue curve, or the demand curve, is perfectly elastic.

- A perfectly elastic average revenue curve indicates that an individual firm experiences a constant average revenue, or price. This means that no matter how much of the product the firm sells, the price remains the same.

- When the price stays the same, the marginal revenue (the revenue gained from selling one more unit) is equal to the average revenue. Therefore, the average revenue curve and the marginal revenue curve are the same, appearing as horizontal lines on a graph.

Relationship Between TR, AR, and MR

Definition of Marginal Revenue (MR)

- Marginal Revenue (MR) is the additional revenue generated from selling one more unit of a product. It is calculated as the derivative of Total Revenue (TR) with respect to quantity (Q), expressed as: MR = dTR/dQ.

Total Revenue (TR) and Marginal Revenue (MR)

- When a firm sells additional units at a lower price, the MR can be less than the price at which the unit is sold. This is because lowering the price to sell an additional unit also affects the price of previously sold units.

- For instance, if the price is reduced to sell the third unit, the two units that were previously sold at a higher price will also have to be sold at the lower price, leading to a loss in total revenue.

- Therefore, in cases where the average revenue (or price) is falling, the MR will always be less than the price.

- Conversely, when the average revenue (or price) is constant, the MR equals the average revenue (or uniform price).

Relationship Between AR, MR, and TR

- When the demand curve is downward sloping, there is a clear relationship between average revenue (AR), marginal revenue (MR), and total revenue (TR).

- The AR curve slopes downwards, indicating the inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded.

- The MR curve lies below the AR curve, showing that MR declines more rapidly than AR.

- TR increases as long as MR is positive and starts to decline when MR becomes negative.

- The TR curve initially increases at a diminishing rate due to decreasing MR, reaches its maximum when MR is zero, and then starts to fall.

Average Revenue Curve in Different Market Structures

- In all forms of imperfect competition, the average revenue curve of an individual firm slopes downwards. This means that when a firm increases the price of its product, the quantity demanded decreases, and vice versa.

- In perfect competition, however, firms are price takers, and the average revenue (or price) curve is perfectly elastic. This means that an individual firm has a constant average revenue (or price).

- When the average revenue is constant, the marginal revenue is equal to the average revenue, leading to the AR and MR curves coinciding. In this case, both curves are horizontal, as shown in the relevant figure.

Relationship between AR, MR, TR and Price Elasticity of Demand

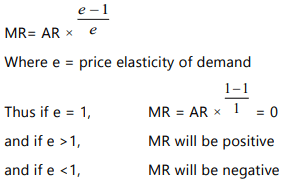

Marginal revenue (MR), average revenue (AR), and price elasticity of demand are interrelated through the formula:

In a downward-sloping demand curve, the price elasticity at the midpoint is one, making MR zero at that point. Above this point, where elasticity is greater than one, MR is positive. Below this point, where elasticity is less than one, MR is negative. This relationship is illustrated in diagrams. In the diagrams, DD represents the AR or demand curve. At point C, where elasticity is equal to one, MR is zero. The MR curve touches the X-axis at point N, corresponding to point C on the AR curve. As quantity increases beyond ON, elasticity becomes less than one, and MR becomes negative, indicating that total revenue (TR) will decrease if quantity exceeds ON. TR increases up to ON output, where MR remains positive. The maximum TR occurs at the point where elasticity is equal to one, indicated by point C on the AR curve. Beyond this point, the TR curve slopes downward.

Behavioural Principles

Principle 1: Shutdown Decision

- A firm should only produce if it can cover its total variable costs.

- If total revenues are less than total variable costs, it’s better for the firm to shut down.

- A competitive firm should cease production if the price is below the Average Variable Cost (AVC).

- At this point, the firm minimizes its losses, as its total cost will equal its fixed costs, resulting in an operating loss equal to its fixed costs.

- The sunk fixed cost is not relevant to the shutdown decision because fixed costs are already incurred.

- The minimum Average Variable Cost (AVC) is the shutdown price, the price at which the firm stops production in the short run. Shutting down is a temporary measure and does not imply going out of business.

Price and Cost Relationships:

- If price (Average Revenue) is greater than minimum AVC but less than minimum Average Total Cost (ATC), the firm covers its variable costs and part of its fixed costs.

- If price equals minimum ATC, the firm covers both fixed and variable costs, earning a normal profit or zero economic profit.

- If price is greater than minimum ATC, the firm covers its full costs and earns a positive economic profit or supernormal profit.

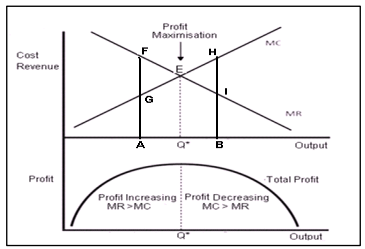

Principle 2: Profit Maximization

- A firm maximizes profits by expanding output until Marginal Revenue (MR) equals Marginal Cost (MC).

- Producing additional units is beneficial as long as MR exceeds MC, meaning the additional units contribute more to revenue than to cost.

- The point where MR equals MC is where the firm achieves maximum profits.

- To achieve the best results, the company will aim to increase profits when marginal revenue is the same as marginal cost.

|

86 videos|255 docs|58 tests

|

FAQs on Unit 1: Meaning and Types of Markets Chapter Notes - Business Economics for CA Foundation

| 1. What is a market in economics? |  |

| 2. What are the main types of market structures? |  |

| 3. How do total revenue, average revenue, and marginal revenue differ? |  |

| 4. What is the relationship between TR, AR, and MR? |  |

| 5. How does price elasticity of demand relate to AR and MR? |  |