Law of Torts Chapter Notes | Legal Studies for Class 12 - Humanities/Arts PDF Download

Introduction

- Tort means a wrong. It comes from the Latin word tortum, which means twisted or crooked.

- In legal terms, a tort is defined as a civil wrong or a wrongful act that can be either intentional or accidental. This act causes injury or harm to another person.

- The injured person can seek civil remedies for damages or ask for a court order or injunction.

- According to Sir John Salmond, a well-known legal scholar, a tort is a civil wrong for which the remedy is a common law action for unliquidated damages.

- This does not only apply to breach of contract, breach of trust, or other equitable obligations.

- M.C. Setalvad, the first Attorney General of India, stated that the law of torts is a tool to ensure that people follow standards of reasonable behavior and respect each other's rights and interests.

- In tort law, damages are meant to be compensatory, putting the defendant back in the position they would have been in if the wrongful act had not happened.

- The remedy often involves unliquidated damages, which are amounts that cannot be predicted or calculated using a set formula.

- Unliquidated damages are those that cannot be easily identified or are subject to unexpected events that affect how much should be paid.

- Tort is a type of civil wrong, which is different from a criminal wrong.

- The elements and procedures in civil law and criminal law are not the same.

- In a criminal case, the state starts legal action in a criminal court on behalf of the victim.

- If the accused is found guilty, they may face punishments decided by the court.

- A civil action, such as a tort lawsuit, is taken in a civil court.

- In civil cases, the person who was harmed, or their representatives, seek to hold the wrongdoer accountable.

- The goal of a tort case is usually to get compensation in the form of money damages.

- Sometimes, people also seek other forms of relief or injunctions.

- Tort cases aim to help the victim, while criminal cases often lead to punishments like jail time.

- Injunctions are court orders that can stop the wrongdoer from harming the victim or from entering the victim's property.

- Occasionally, courts may award punitive damages, which are extra amounts beyond normal compensation to punish the wrongdoer.

- A tort can happen either on purpose or by mistake.

- It includes harmful actions such as:

- Battery and assault (which can cause physical or emotional harm to someone).

- Nuisance (an action that bothers or harms the public or an individual).

- Defamation (when someone's reputation is damaged).

- Property damage.

- Trespass (entering someone’s land or property without permission).

- Negligence (careless behavior).

- Some of these wrongful acts may also relate to other areas of law, like criminal law and contract law.

- This chapter will focus on the basic features of tort law related to these wrongs.

- The three main elements of a tort are:

- Wrongful act.

- Damage.

- Remedy.

Sources of Law of Torts

- Tort law primarily originates from Common Law, evolving over time through judicial decisions rather than statutory provisions.

- In India, tort law is based on centuries of case law from English courts and other Common Law jurisdictions like Canada, Australia, and the United States.

- Unlike criminal law (e.g., Indian Penal Code) and contract law (e.g., Indian Contract Act), which are statutory, tort law lacks a comprehensive statute governing it.

- Tort lawyers must examine case law and precedents to identify tortious wrongs, as there is no single statute like the Contract Act guiding tort cases.

- While tort law includes statutes, it is primarily rooted in case law and cannot be traced to a single legislative source.

Kinds of Wrongful Acts

There are three primary types of wrongful acts in tort law:

- Intentional Wrongs: These occur when the wrongdoer deliberately causes harm to the victim. Examples include assault, battery, false imprisonment, and invasion of privacy.

- Negligent Wrongs: These arise when the wrongdoer fails to exercise reasonable care, leading to unintended harm to the victim. For instance, car accidents due to reckless driving fall under this category.

- Strict Liability Wrongs: In such cases, the defendant is held liable for the harm caused, regardless of intent or negligence. This applies to activities that pose a high risk of harm, such as keeping dangerous animals or carrying hazardous substances.

Intentional Torts

Intentional torts involve cases where the defendant deliberately causes harm to the claimant. To establish an intentional tort, the claimant must demonstrate that:

- The defendant acted with the intention to cause harm or offense.

- The claimant suffered a specific injury or consequence as a result of the defendant's actions.

- There is a causal link between the defendant's actions and the harm suffered by the claimant.

Types of Intentional Torts

(a) Battery:

- Battery occurs when the defendant intentionally applies physical force to the claimant, causing harm or offense. Both intent and causation are essential for establishing battery.

- The act of touching does not always require the defendant's hands; it can involve any form of contact, such as throwing hot water at someone.

(b) Assault:

- Assault involves the defendant intending to create a reasonable apprehension in the claimant of imminent harmful or offensive contact.

- For example, if the defendant throws an object at the claimant but misses, causing the claimant to fear harm, it constitutes assault.

- Assault can occur without battery, such as pointing an unloaded gun at someone who is unaware of its condition.

(c) False Imprisonment:

- False imprisonment occurs when the defendant intentionally confines or restrains the claimant in a bounded area without legal authority.

- The claimant must be aware of the confinement for the tort to be established, although harm can substitute for awareness in some cases.

- For instance, locking someone in a room without consent constitutes false imprisonment.

(d) Trespass to Land:

- Trespass to land involves the defendant intentionally interfering with the claimant's possession of land by invading their property without consent.

- This can include physical invasion of land, airspace above the land, or subsurface areas below the land. Examples include littering on someone's property or creating unauthorized drainage systems.

(e) Trespass to Chattels:

- Trespass to chattels occurs when the defendant interferes with the claimant's lawful possession of movable personal property (chattels) without consent.

- This can involve significant deprivation of use, damage to condition or value, or harm to the claimant's legal interest in the chattel.

- For instance, painting someone's parked car without permission constitutes trespass to chattels.

(f) Conversion:

- Conversion is related to trespass to chattels and involves wilful interference with a chattel in a manner inconsistent with another's rights.

- The defendant deprives the rightful owner of use and possession of the chattel without lawful justification. Examples include selling someone else's property without permission.

Unlawful harassment and Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress

- A defendant can be held liable for any act of deliberate physical harm to the victim, even in the absence of battery or assault.

- For instance, if the defendant deceives the claimant by saying their son was involved in a road accident, causing the claimant to experience nervous shock and illness, it constitutes unlawful harassment.

- Sexual harassment can also fall under unlawful harassment.

- For example, stalking someone, sending unwanted messages or phone calls, even without violence or threats, amounts to harassment.

Defamation

- Defamation is the act of publishing a statement that lowers a person’s reputation in the eyes of society, making them shun or avoid that individual.

- It involves intentional false communication, either written or spoken, that harms a person’s reputation, diminishes the respect or confidence they receive, or induces negative opinions or feelings against them.

- Defamation can be both a tort and a crime.

- Criminal Defamation involves offending or defaming a person by committing a crime, and the liable person can be prosecuted under the Indian Penal Code (IPC).

- Civil Defamation does not involve a criminal offense, but the claimant can sue for compensation under the law of torts.

- In English law, defamation is divided into Libel and Slander.

- Libel refers to defamation in a permanent form, such as writing or pictures, and is recognized as an offense under English Criminal Law.

- Slander refers to defamation in a transient form, like spoken words or gestures, and is actionable under the law of torts in English law.

Negligence

- Negligence refers to the breach of a duty to take care, resulting in damages. It implies that the defendant has been careless in a way that harms the interests of the victim or claimant.

- For example, when a defendant undertakes construction on their premises, they owe a duty of care to the claimant and others in proximity. The standard of duty of care varies based on the claimant’s presence on the site and their status as a lawful visitor or trespasser.

- To establish a case of negligence, the victim or claimant must prove three elements: (1) the defendant owes a duty of care to the victim, (2) there has been a breach of this duty, and (3) the breach resulted in harm to the claimant.

- Duty of Care. This principle is exemplified in the case of Donoghue v Stevenson, where the court held that manufacturers owe a duty of care to those who are reasonably foreseeable to be affected by their products. For instance, a landlord has a duty of care to tenants to ensure hazardous materials are not stored in their premises.

- Breach of Duty of Care. Once duty of care is established, the claimant must prove that the defendant failed to meet this duty according to the standard of reasonableness. The act need not be perfect, but should align with reasonable conduct. In Donoghue v Stevenson, the court ruled that product manufacturers owe a duty of reasonable care to consumers. The standard of reasonable care varies based on the specific circumstances of each case.

Harm to the Claimant

Donoghue v Stevenson

- In this case, the claimant fell ill because the manufacturer of the soft drink was negligent.

- Similarly, in another scenario, tenants suffered damage when an apartment caught fire due to petrol being improperly stored in the basement.

MacPherson v. Buick Motor Co. (1914)

- In this well-known American case, the plaintiff purchased a car from a retail dealer and was injured when a defective wheel collapsed.

- The plaintiff sued Buick Motor Co., the car's original manufacturer, for negligence, even though the wheel was made by another manufacturer.

- The court found Buick responsible for the entire finished product and ruled that they could not sell it without inspecting its components.

To establish a duty of care towards end consumers, it must be demonstrated that:

- The product's nature poses a probable danger to life and limb if made negligently.

- There is an expectation that this danger will affect people other than the buyer in the usual course of events, based on the nature of the transaction and the relationship between the parties.

The court determined that the manufacturer intended for the product to be used without inspection by customers. If the manufacturer was negligent and the danger was foreseeable, they would be liable.

No-Fault Liability

Definition: No-fault liability arises when a defendant is held responsible for violating a claimant's rights, even without any fault on the defendant's part. This type of liability is applicable in situations where the defendant's actions do not constitute a breach of duty, but the claimant's rights are still infringed upon.

Types of No-Fault Liability: No-fault liability encompasses two main types:

- Absolute Liability: This refers to situations where a defendant is liable for the consequences of their actions, regardless of fault or intention. It applies when a defendant possesses something inherently dangerous, as defined by the concept of 'ultrahazardous' activities. For example, if a defendant owns a hazardous substance that escapes and causes harm, they are strictly liable for the damages, irrespective of the precautions taken.

- Strict Liability: Strict liability holds a defendant responsible for the outcomes of their actions, even in the absence of fault or criminal intent. This principle was established in the case of Rylands vs. Fletcher in 1868. In this case, Rylands, a mill owner, constructed a water reservoir on his land to power his mill. Due to the negligence of an independent contractor, the reservoir leaked water into Fletcher's mines, causing significant damage. Despite Rylands' defense that he was not directly involved in the construction and had taken reasonable care, the court ruled that he was liable for the damages caused by the escape of water from his land.

Principles of Strict Liability: The case of Rylands vs. Fletcher established three fundamental principles of strict liability:

- Dangerous Thing: The presence of a dangerous substance or activity on the defendant's land constitutes a non-natural use of the land, which gives rise to liability.

- Escape: The escape of the dangerous substance from the defendant's land is a crucial factor in establishing liability. In the Rylands case, the escape of water from Rylands' land into Fletcher's mines was the basis for the claim.

- Liability: The defendant is liable for the damages caused by the escape of the dangerous substance. In this case, Rylands was held responsible for the losses incurred by Fletcher due to the escape of water from his land.

Application of Strict Liability: Strict liability applies when a person brings something dangerous onto their land, and it escapes, causing damage. The defendant can be held liable even if they took precautions to prevent the escape. This principle is based on the idea that certain activities or substances are inherently hazardous and pose a risk to others.

Exceptions to Strict Liability

Plaintiff’s Own Fault: If the damage is caused by the claimant's own actions or negligence, they cannot claim damages.

Act of God: This defense is used when damage is caused directly by natural events without human interference.

Mutual Benefit: If the plaintiff has given consent, whether express or implied, to the risk that caused the damage, and the defendant was not negligent, then the defendant is not liable.

Act of Stranger: If the damage is caused by someone who is neither associated with nor controlled by the defendant, then this can be used as a defense.

Statutory Act: This defense applies if the damage results from an action authorized by the government or a corporation.

Absolute Liability in India

In India, the principle of absolute liability was established in response to major industrial disasters. This principle was significantly defined after two catastrophic gas leaks:

Bhopal Gas Leak, 1984: At Union Carbide Corporation in Bhopal, a leak of methyl isocyanate gas resulted in over 2,260 deaths and around 600,000 injuries.

Delhi Oleum Gas Leak, 1985: A leak from Shri Ram Foods and Fertilizers led to one death, several hospitalizations, and widespread panic.

In the landmark 1987 case of M.C. Mehta v. Shri Ram Foods and Fertilizers, Chief Justice P.N. Bhagwati asserted that industries involved in hazardous activities owe a non-delegable duty to ensure community safety. The principle of absolute liability holds that if an industry's activities, which aim to profit and are inherently dangerous, cause any harm, it must provide compensation without claiming any defense of due diligence or absence of negligence.

Key Principles of Absolute Liability:

Enterprise with Commercial Objectives: The enterprise aims to make a profit.

Hazardous or Inherently Dangerous Activities: The industry is engaged in activities that pose significant risks.

No Requirement for Escape: Unlike strict liability, there is no need for the hazardous material to escape from the premises for the liability to apply.

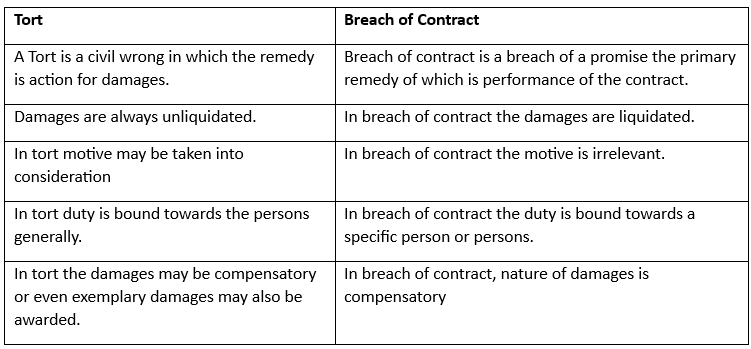

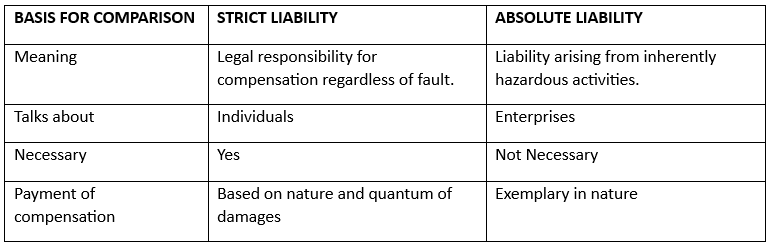

Differences Between Strict Liability and Absolute Liability

- Strict Liability refers to the legal responsibility of a person to compensate for damages, regardless of fault or negligence. It applies when hazardous components escape from a person's premises. Defendants in strict liability cases may have certain exceptions to avoid liability, and compensation is based on the nature and extent of damages.

- Absolute Liability, on the other hand, is applicable to enterprises engaged in inherently dangerous activities, such as keeping dangerous animals or using explosives. In absolute liability cases, escape of hazardous components is not necessary, and defendants have no exceptions. Compensation is determined by the magnitude and financial capability of the organization, and damages are typically exemplary in nature.

Summary of the Types of Harms

The examples of the various ways in which the claimant can suffer injuries, as discussed in this chapter, are summarized below.

- Property Interests in Land: The law of tort safeguards the claimant's interests in their landed property by preventing intentional intrusions or trespass by the defendant or wrongdoer. Harm can also occur due to the defendant's carelessness or negligence. When the defendant interferes with the claimant's right to enjoy their land, it constitutes the tort of nuisance.

- Other Types of Property: Tort law prohibits the deliberate taking away of tangible property, which amounts to the tort of 'conversion.' Damage to property can also occur due to carelessness or negligence.

- Bodily Injury: Tort law protects the claimant against any harm to their bodily integrity. The torts of battery and assault apply to intentional harm caused to the body. Harm can also result from negligence or a breach of statutory duty, such as traffic or health laws. Mental distress is an element in bodily injury that can increase compensation for the victim.

- Economic Interests: To a lesser extent, economic interests are also protected by tort law. Injury caused by intentional acts or negligence can result in economic harm to the claimant.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it can be stated that, unlike a crime, the law of torts does not aim to punish the wrongdoer. Instead, it seeks to restore the aggrieved person to the position they were in before the cause of action arose, thus providing restorative justice.

|

98 videos|69 docs|30 tests

|

FAQs on Law of Torts Chapter Notes - Legal Studies for Class 12 - Humanities/Arts

| 1. What are the main types of wrongful acts in tort law? |  |

| 2. How do torts differ from crimes? |  |

| 3. What types of harms can result from tortious acts? |  |

| 4. Can an individual sue for emotional distress in tort law? |  |

| 5. What is the significance of duty of care in negligence cases? |  |