Law of Property Chapter Notes | Legal Studies for Class 12 - Humanities/Arts PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Introduction |

|

| Types of Property |

|

| Transfer of Property |

|

| Doctrine of Election |

|

| Doctrine of Lis Pendens |

|

| Mode of Transfer |

|

Introduction

Before the British rule, different communities in India followed their own customary laws for property transfers. When the British established a formal legal system, there was no specific legislation for property transfer, so English judges used common law and principles of equity, justice, and good conscience to resolve disputes. However, these English laws were not suitable for Indian conditions, leading to conflicts and the need for clearer rules.

To address this, the Transfer of Property Act was drafted in 1870 and enacted in 1882, providing foundational principles for transferring both movable and immovable properties. While based on English law, the Act aimed to adapt these principles to Indian circumstances.

A separate law, the Sale of Goods Act, 1930, was introduced to govern the transfer of movable property through sale. The Transfer of Property Act, 1882 outlines general principles of property transfer and specific rules for transferring immovable property through sale, exchange, mortgage, lease, and gift.

Types of Property

1. Definition of Property

- Property, as per the Act, encompasses a wide range of items, including movable properties like cases and books, immovable properties such as land and houses, and intangible properties like ownership, tenancy, and copyrights.

2. Immovable Property

- Immovable property, according to Section 3, does not include standing timber, growing crops, and grass.

- Standing Timber: This refers to trees suitable for use in building or repairing houses. Examples include Babool, Shisham, Peepal, Banyan, Teak, and Bamboo. Fruit-bearing trees like Mango, Jackfruit, and Jamun are considered immovable properties.

- Growing Crop: This includes vegetable growths that exist only in relation to their produce, such as pan leaves and sugarcane.

- Grass: While grass is generally considered movable property, the right to cut grass constitutes an interest in land, making it immovable property.

3. Trees as Property

- Whether trees are regarded as movable or immovable property depends on the circumstances. If the intention is to allow the trees to continue benefiting from the land, such as by bearing fruit, they are considered immovable property. However, if the intention is to cut them down for wood, they are regarded as timber and thus movable property.

4. General Understanding of Immovable Property

- Immovable property includes land, benefits arising from land, and things permanently attached to the earth or fastened to anything attached to the earth.

5. Movability Definition

- Movability is defined as the capacity of an object to undergo alteration. If an object cannot change its location without compromising its quality, it is considered immovable.

6. Legal Cases and Definitions

- In the case of Sukry Kurdepa v. Goondakull (1872), movability is explained in terms of a thing's capacity to suffer alteration.

- In Marshall v. Green (33 LT 404), the court ruled that the sale of cut and removed trees did not constitute a sale of immovable property.

7. Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Act, 1988

- Property is defined as any kind of property, whether movable or immovable, tangible or intangible, including any right or interest in such property.

8. Sale of Goods Act, 1930

- Property is defined as the general property in goods, not merely a special property.

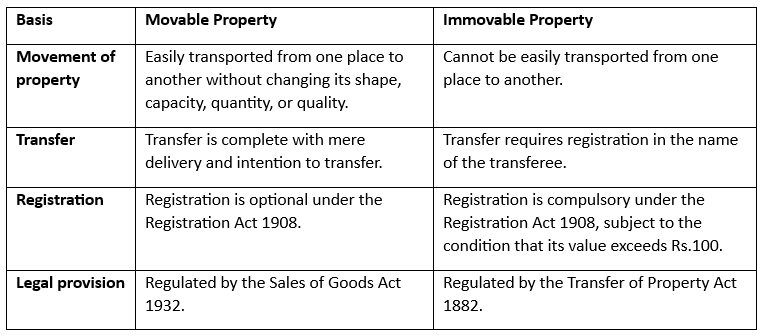

9. Comparison between Movable and Immovable Property

Transfer of Property

The Transfer of Property refers to the act of conveying property from one person to another, either in the present or future. In India, matters relating to the transfer of property are governed by the Transfer of Property Act, 1882. The primary objective of this Act is to regulate the transfer of property between living persons and to serve as a code of contract law governing immovable property.

The Transfer of Property Act, 1882 provides a systematic and uniform legal framework for the transfer of immovable property in India. Property can also be transferred by inheritance and succession, which are governed by respective religious laws or practices.

Who can transfer property?

- Any person who is competent to contract, such as an individual above 18 years of age, having a sound mind, and not disqualified by law, can transfer property.

- The transferor, who is the person transferring the property, must be the owner or authorized to sell the property.

- According to Section 8 of the Transfer of Property Act 1882, the transferor transfers all rights in the property to the transferee.

Essentials of a valid transfer

- Living Persons: The transfer must be between two or more living persons.

- Transferable Property: The property should be free from encumbrances and of a transferable nature.

- Lawful Purpose: The transfer should not be for an unlawful object or consideration.

- Competence: The transferor must be competent to make the transfer and entitled to the property.

- Authorization: If the property is not owned by the transferor, they must be authorized to dispose of it.

- Mode of Transfer: The transfer should be made according to the appropriate mode, complying with necessary formalities like registration and attestation.

- Conditional Transfers: In case of conditional transfers, the condition should not be illegal, immoral, impossible, or against public policy.

How can property be transferred?

1. Mode of Transfer

Tangible Property:

- Value > Rs. 100: Transfer must be done through a registered instrument.

- Value < Rs. 100: Transfer can be made by delivery.

Intangible Property:

- Regardless of Value: Transfer must be done by a registered instrument.

2. Attestation:

- A registered instrument requires attestation by at least two witnesses.

- Attestation Definition: Affixing signatures to the instrument for property transfer.

- Witness Intention: Witnesses must sign with the intention to attest, ensuring the transfer is voluntary.

3. Registration

- Registration is a crucial legal step for transferring immovable property.

- Parties' Presence: Both parties must be present to sign the document during registration.

- Document Requirements: The document must clearly outline the rights, obligations, and liabilities of both parties.

- Registrar's Seal: Registration is finalized with the Registrar's office seal, and the document is included in official records.

- Indian Registration Act: This act governs the registration of documents, and Section 17 mandates the registration of certain documents.

4. Mutation

- After transferring property through relinquishment, sale, or gift deed, the transfer must be recorded in municipal records through mutation.

5. Payment of Fee

- Stamp duty on the transfer is payable according to the applicable state laws.

In the case of Madam Pillai V. Badar Kali, the court ruled that the plaintiff acquired title through oral transfer and was entitled to the property, even though the instrument of sale was not registered.

Doctrine of Election

The Doctrine of Election, as outlined in Section 35 of the Transfer of Property Act (TPA), pertains to situations where a person receiving a transfer is presented with two options: a benefit and a burden. According to this principle, the recipient must accept both the benefit and the burden or reject both. They cannot selectively accept the benefit while rejecting the burden in a single transaction.

In simpler terms, when claiming the advantages of a legal instrument, one must also accept its associated disadvantages.

Illustration: Let’s say A sells his garden and house to B through a single agreement. If B wants to keep only the house and cancel the transfer of the garden, the Doctrine of Election stipulates that B must keep the garden if he wishes to retain the house, or cancel the entire transaction. B cannot pick and choose which parts of the agreement to accept.

The Doctrine of Election is grounded in the principle of equity, which asserts that one cannot accept what is beneficial while rejecting what is detrimental under the same legal instrument. This concept is encapsulated in the Latin maxim “quod approbo non reprobo,” meaning that no one can approbate and reprobate simultaneously. In essence, when a person accepts a benefit under a deed or instrument, they must also bear its burden.

The principle was further clarified in the case of Cooper v. Cooper by the House of Lords. Lord Hather in this case explained that when someone takes a benefit under a will or instrument, they are obligated to give full effect to that instrument. If the instrument deals with something beyond the donor’s power to dispose of, the law will impose on the beneficiary the obligation to carry the instrument into full effect.

Section 35 of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882, encapsulates the Doctrine of Election, which applies to all instruments and types of property.

Doctrine of Lis Pendens

The Doctrine of Lis Pendens is outlined in Section 52 of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882. The term "lis pendens" refers to a "pending suit."

According to this doctrine, when a property is involved in a legal dispute, it should not be transferred to a third party in a manner that affects the rights of any party involved in the case. Essentially, no new interests in the property should be created through transfer while the lawsuit is ongoing.

The doctrine is rooted in the Latin maxim "ut lite pendent nihil innovetur," which means "nothing new should be introduced in a pending litigation." Its purpose is to ensure that all parties involved in a legal dispute over a property are bound by the court's decision, reflecting the court's control over the property until a final judgment is reached.

When a lawsuit or legal proceeding is pending regarding immovable property, that property cannot be transferred.

For the Doctrine of Lis Pendens to apply, certain conditions must be met:

- There must be a pending suit or proceeding involving the immovable property.

- The right to the immovable property must be in question in the suit or proceeding.

- The property in litigation should be transferred.

- The transfer of the property should affect the rights of other parties involved.

Illustration: If A is in a legal dispute with X over the title of a property, and A tries to sell the property to B during the litigation, the sale would be invalid under the Doctrine of Lis Pendens because the property is subject to ongoing legal proceedings.

In the case of Dev Raj Dogra and others v Gyan Chand Jain and others, the Supreme Court interpreted Section 52 of the Transfer of Property Act and established certain preconditions:

- A suit or proceeding must be pending where the right to immovable property is directly and specifically in question.

- The suit or proceeding should not be collusive.

- The property cannot be transferred or dealt with in a way that affects the rights of other parties without court authority during the pendency of the suit.

The Supreme Court clarified that Section 52 does not render a pendente lite transfer void or illegal but binds the pendente lite purchaser to the outcome of the ongoing litigation. This means that if a party to the suit transfers immovable property during the litigation, affecting the rights of other parties, the transfer is prohibited unless authorized by the court.

In summary, the Doctrine of Lis Pendens restricts the transfer of immovable property involved in a legal dispute to protect the rights of all parties and uphold the court's authority until a final decision is reached.

Mode of Transfer

Sale

A sale involves the transfer of ownership of a property in exchange for a price, typically money. In this context, the seller is the person transferring the property, while the buyer is the one receiving it. The consideration in a sale is usually monetary.

Illustration: If A sells his house to B for Rs. 2 lakhs, this constitutes a sale where A is the seller, B is the buyer, and Rs. 2 lakhs is the consideration.

Essentials for a Valid Sale

- There must be two distinct parties: the seller and the buyer.

- Both parties should be competent to transfer the property.

- The property being transferred must be in existence.

- The consideration for the transfer should be in the form of money.

- The contract must comply with legal requirements.

Lease

A lease, as per the Transfer of Property Act, is a contract where one party transfers the right to enjoy land, property, services, etc., to another party for a specified period, usually in exchange for periodic payments. Importantly, a lease does not constitute a sale. According to Section 105 of the TPA, a lease can only be applied to immovable property.

Key Aspects of a Lease

- A lease involves transferring the right to enjoy a property for a specific duration in consideration of a price.

- The lessor is the person who leases out the property, while the lessee is the one receiving the lease.

- The lessee has the option to sub-let the lease, creating a relationship similar to that of the lessor and lessee.

Subleasing Explained

- A sublease occurs when a tenant rents out a portion of their leased property to a third party for a part of their existing lease term.

- Despite subleasing, the original tenant remains responsible for the lease obligations, including monthly rent payments.

- Subleasing is legal in India with the landlord's consent.

- If permitted by the lease agreement, a tenant can sublease a portion of the property to a third party.

- Subleasing involves a tenant renting out a room, part, or all of the property to another individual, known as the subtenant.

- The subtenant must pay rent and adhere to the lease terms, but the principal tenant retains ultimate responsibility for the lease.

Illustration: If A leases his property to B for three years at Rs. 50,000, this is a lease agreement. If B subsequently sublets the property to C, B becomes the lessee, and C the sub-lessee, establishing a relationship similar to that of A and B.

Exchange

Exchange involves the transfer of ownership between two parties, where each party gives ownership of one thing for another. According to Section 118 of the TPA, property can only be transferred by way of sale in an exchange. The rights and liabilities of the parties involved in the exchange are determined by the rights and liabilities of the buyer and seller.

Illustration: If A offers to sell his cottage to B, and B, in return, sells his farm to A, this is an example of an exchange. A receives a farm instead of money for his cottage, and his rights and liabilities are those of a seller towards the sale of the cottage and a buyer towards the sale of the farm. Similarly, B's rights and liabilities are those of a buyer towards the sale of the cottage and a seller towards the sale of the farm.

Gift

A gift, as defined in Section 122 of the TPA, is a voluntary transfer of ownership of property without any consideration. The person making the transfer is called the donor, while the person receiving it is called the donee. If the donee passes away before accepting the gift, it becomes void.

Illustration: If A gives his car to B without expecting anything in return, this is a gift. A is the donor, and B is the donee.

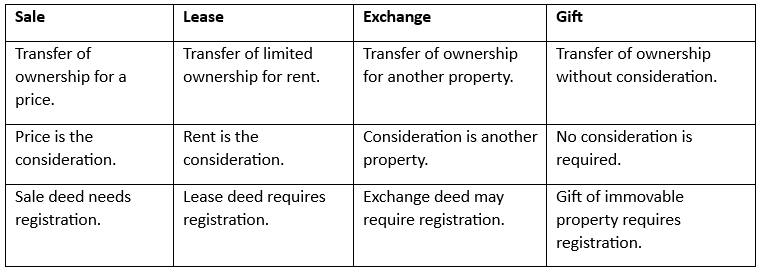

Comparison

|

98 videos|69 docs|30 tests

|

FAQs on Law of Property Chapter Notes - Legal Studies for Class 12 - Humanities/Arts

| 1. What are the different types of property recognized in law? |  |

| 2. How is property transferred legally? |  |

| 3. What is the Doctrine of Election in property law? |  |

| 4. Can you explain the Doctrine of Lis Pendens? |  |

| 5. What are the key learning outcomes of studying the law of property? |  |