Judiciary - Constitutional, Civil and Criminal Courts and Processes Chapter Notes | Legal Studies for Class 11 - Humanities/Arts PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Introduction |

|

| Judiciary in India: Constitution, Functions, and Impartiality |

|

| The Structure of Civil Courts |

|

| Structure and Functioning of Criminal Courts in India |

|

| Other Courts in India |

|

Introduction

Judiciary in India is a vital part of the country’s governance, ensuring that the rule of law is upheld and the rights of citizens are protected. It operates independently from the legislature and executive, maintaining the separation of powers as outlined in the Constitution. The judiciary has the power to interpret the Constitution, review laws and executive actions, and resolve disputes. Supreme Court is the highest court in the country, followed by the High Courts in each state. The judiciary's role is crucial in safeguarding democracy, ensuring justice, and promoting social and economic development.

Establishment of Supreme Court and High Courts

Historical BackgroundAfter gaining independence in 1947, India adopted the Constitution on 26 January 1950, establishing the Supreme Court as the highest judicial authority in the country.

The Supreme Court succeeded the Federal Court, with Justice Harilal Jekisundas Kania becoming its first Chief Justice.

The Supreme Court's jurisdiction is considered one of the most extensive in the world, surpassing that of comparable courts globally.

Structure and Jurisdiction

The original Constitution provided for a Supreme Court with a Chief Justice and seven judges, allowing Parliament to increase the number of judges as needed.

The Supreme Court operates in smaller benches of two or three judges, forming larger benches of five or more to resolve significant issues or differences in opinion.

The Supreme Court has three main types of jurisdiction:

- Federal Jurisdiction: Exclusive original jurisdiction in disputes involving the Government of India and states, or between states.

- Appellate Jurisdiction: Hearing appeals from State High Courts on civil, criminal, and constitutional matters.

- Special Jurisdiction: Discretionary power to grant special leave to appeal under Article 136, and advisory jurisdiction under Article 143.

The Supreme Court shares concurrent original jurisdiction with High Courts for enforcing fundamental rights under Article 32.

Parliament can enlarge the Supreme Court's jurisdiction, and the Court can issue orders for complete justice.

The Supreme Court's decisions are binding on all courts in India, as per Article 141 of the Constitution.

Judicial Review and Constitutional Authority

The Supreme Court has the power of judicial review, allowing it to strike down legislative and executive actions that violate the Constitution or fundamental rights, or exceed the powers granted by the Constitution.

Judicial review also applies to the distribution of powers between the Union and the States.

The President of India appoints Supreme Court judges in consultation with other judges, and can remove them for misbehavior or incapacity, following a special parliamentary procedure.

The Supreme Court is tasked with ensuring social, economic, and political justice, and upholding the principles of equality, liberty, dignity, and democracy as enshrined in the Constitution.

The judiciary plays a crucial role in realizing the aspirations and values embedded in the Constitution, and even constitutional amendments are subject to judicial scrutiny.

The judiciary is seen as the guardian of the Constitution, responsible for upholding the rule of law and protecting the rights and freedoms of citizens.

Basic Structure Doctrine

What is the Basic Structure Doctrine?

- The Basic Structure Doctrine is a principle established by the Supreme Court of India in the Kesavananda Bharati case in 1973. It states that while the Constitution can be amended, the fundamental framework or 'basic structure' cannot be altered.

- This means that there are limits to how much the Constitution can be changed, protecting its core values and principles.

Evolution of the Doctrine

- After the President’s Rule case in 1994, the Basic Structure Doctrine was expanded.

- It was no longer just about the constitutional validity of amendments but also applied to the actions of the legislature and executive.

- This means that the exercise of power by these bodies is also subject to the Basic Structure limitation.

Role of High Courts

- High Courts in India, of which there are 25, play a crucial role in upholding the Constitution and the Basic Structure Doctrine.

- They handle a significant amount of work, including appeals from lower courts and writ petitions under Articles 226 and 227 of the Constitution.

- Writ petitions allow individuals to seek legal remedies for violations of their rights, and High Courts have the authority to hear cases that do not fall within the jurisdiction of subordinate courts due to territorial or pecuniary limitations.

- Additionally, High Courts can hear certain matters as part of their original jurisdiction if provided by law.

Judiciary in India: Constitution, Functions, and Impartiality

The Judiciary in India is a continuation of the British legal system, with the Supreme Court at its head. Below the Supreme Court are 25 High Courts, which oversee numerous District Courts.

Constitution and Powers

- Article 129. This article designates the Supreme Court as a 'court of record', granting it the authority to punish for contempt, including contempt of subordinate courts.

- Article 141. This article states that the law declared by the Supreme Court is binding on all courts in India.

Role of the Judiciary

- The judiciary is responsible for interpreting and applying the law to resolve disputes among citizens, states, and other parties.

- It upholds the rule of law and protects civil and political rights.

- Courts also safeguard the supremacy of the Constitution by interpreting its provisions and ensuring that all authorities operate within its framework.

Federal Disputes

- In a federal system, the judiciary has the task of resolving disputes between states and between the Union and the states.

- The Supreme Court acts as an arbiter in these cases, examining laws to ensure they fall within the legislative competence of the enacting body.

Principles of Legal Interpretation

- Doctrine of Pith and Substance. This doctrine helps determine the true nature of legislation by considering its overall object, scope, and effect.

- Doctrine of Severability. This principle allows for the separation of unconstitutional provisions of a statute from those that are valid, ensuring the latter remain enforceable.

- Doctrine of Colourable Legislation. This doctrine prevents legislatures from enacting laws indirectly that they could not enact directly due to constitutional restrictions.

Case Laws

State of Maharashtra v. FN Balsara

Facts

- The State of Maharashtra enacted a law imposing a limit on the maximum quantity of liquor (both domestic and imported) that could be held by any dealer or wholesaler.

- The petitioner, FN Balsara, was dissatisfied with this law and challenged it in the Supreme Court, arguing that the law improperly regulated the quantity of imported liquor, which fell under the Union List. He contended that the state government was not authorized to make such a law.

- The state government defended the law, asserting that its purpose was to regulate the consumption of liquor within the state, not to govern import and export. The cap applied to both domestic and foreign liquor.

Issue

- The key issue was whether the law enacted by the state government was valid or violated Article 246 of the Constitution.

Decision

- The Supreme Court ruled that when assessing the validity of a law, the Act should be considered in its entirety to grasp its essence. In this case, the essence of the law was not about regulating import and export but about controlling liquor consumption within the state. Since this matter falls under the State List, the law was deemed valid.

Balaji v. State of Mysore

- The government of Mysore implemented reservations totaling 51% under Article 16 of the Constitution.

- This action was challenged in the Supreme Court on the grounds that it violated Article 14.

- The government defended its position by stating that the reservations were made under Article 16 and not Article 14.

- The Supreme Court ruled that a law must be legal under all provisions of the Constitution. By invoking only one provision, the government could not disregard another, applying the doctrine of colorable legislation.

- Using the doctrine of severability, the Court upheld 49% of the reservations but invalidated the excess 2%.

Judiciary and Basic Structure

- The power of Parliament to legislate is supreme, but the Judiciary acts as a watchdog of Indian democracy.

- The role of the Judiciary has evolved based on the Constitution and the socio-economic needs of the country.

- The term " basic structure. was first used in the Golaknath case in 1967, and later in 1973, the Supreme Court clarified that it refers to the core features of the Constitution that require special procedures for amendment.

- The Kesavananda Bharati case established that any amendment aiming to abrogate the basic structure is unconstitutional, subjecting proposed amendments to judicial scrutiny.

- Elements of the basic structure include:

- Supremacy of the Constitution

- Republican and democratic government

- Secular character of the Constitution

- Separation of powers between the legislature, executive, and judiciary

- Federal character of the Constitution

- The Judiciary also possesses the power of judicial review, allowing it to scrutinize legislation passed by Parliament.

- The Supreme Court can strike down legislation amending the Constitution if:

- The procedure under Article 368 is not followed

- The amendment violates basic features of the Constitution

Protection of Fundamental Rights

- The Judiciary plays a crucial role in protecting and enforcing the fundamental rights of citizens as guaranteed by the Constitution.

- The Supreme Court monitors the functions of the other branches of government to ensure they operate within the bounds of the Constitution and laws enacted by Parliament and State legislatures.

- The Supreme Court has the authority to issue directions, orders, and writs for the enforcement of fundamental rights under Article 32 of the Constitution.

- These writs include Habeas Corpus, Mandamus, Prohibition, Certiorari, and Quo Warranto, making the Supreme Court a protector of fundamental rights.

- If a law encroaches upon fundamental rights, the Supreme Court can declare it null and void, a power it has exercised on several occasions.

- The concept of Public Interest Litigation (PIL) allows any citizen to bring matters of general importance to the Supreme Court's attention.

- If the Supreme Court finds the executive failing in its duties, it can issue necessary directions to the concerned authorities.

Appellate Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of India has the authority to hear appeals in various constitutional, civil, and criminal matters as outlined in different articles of the Constitution.Appeal in Constitutional Matters

- According to Article 132 (1) of the Constitution, the Supreme Court can hear appeals from High Court judgments, decrees, or final orders in civil, criminal, or other proceedings if the High Court certifies under Article 134-A that the case involves a substantial question of law regarding the interpretation of the Constitution.

Appeal in Civil Cases

- Article 133 states that an appeal to the Supreme Court from a High Court's judgment, decree, or final order in a civil proceeding is possible only if the High Court certifies under Article 134-A that the case involves a substantial question of law of general importance and that this question needs to be decided by the Supreme Court.

Appeal in Criminal Cases

- Article 134 provides for appeals to the Supreme Court from judgments, final orders, or sentences in criminal proceedings by High Courts. There are two ways for such appeals: with or without a High Court certificate.

Without a Certificate

- An appeal can be made without a High Court certificate if:

- The High Court has reversed an order of acquittal and sentenced the accused to death.

- The High Court has withdrawn a case from a subordinate court, tried it itself, convicted the accused, and sentenced him to death.

Advisory Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of India possesses advisory jurisdiction as well. Article 143 of the Constitution states that if the President believes that: (a) a question of law or fact has arisen or is likely to arise, and (b) the question is of significant public importance and requires the Supreme Court's opinion, the President may refer the question to the Court for advisory opinion. The Court, after hearing the matter, will report its opinion to the President.In the Kerala Education Bill case (1958), the Supreme Court established several principles regarding its advisory jurisdiction:

- The Court has the discretion to refuse to express an opinion on a referred question in appropriate cases and for valid reasons.

- It is the President's prerogative to determine which questions should be referred to the Court.

- The advisory opinion of the Supreme Court is not binding on lower courts because it does not constitute law under Article 141.

However, in the Special Court Bill case (1979), the Supreme Court ruled that its advisory opinions are binding on all courts in India. The Court also emphasized its duty under Article 143 to provide advisory opinions when the questions referred are clear and not politically contentious.

Independence and Impartiality of the Supreme Court

The concepts of “independence” and “impartiality” are fundamental to the functioning of any court, including the Supreme Court. While they are related, they represent different aspects of judicial quality. Impartiality refers to the mindset and attitude of the court towards the issues and parties involved in a case. It means that the court approaches the case without bias or preconceived notions. On the other hand, independence pertains to the court’s relationship with other branches of government, particularly the executive. It involves ensuring that the court operates free from external pressures and influences. Factors Ensuring Judicial Impartiality and Independence Judicial impartiality and independence are crucial for maintaining a fair and efficient system of justice, both between individuals and between individuals and the State. Several factors contribute to these principles:- Historical Context: During the debates of the Constituent Assembly, there were concerns about the limits of judicial review and the independence of the judiciary.

- Jurisdiction: Questions were raised about whether the Supreme Court's jurisdiction should be limited to federal issues or if it should have a broader scope in civil and criminal matters.

- Court System: The idea of a dual court system, similar to that of the United States, was discussed, but India opted for a single integrated system.

- Integrated Judiciary: India established a unified judicial system with the Supreme Court at the top, followed by High Courts and subordinate courts. This system ensures that both Union and State laws are administered under one judicial framework.

- Constitutional Provisions: The Constitution provides various safeguards for judicial independence, such as security of tenure, retirement ages for judges, and protection of judges' emoluments.

- Appointment of Judges: Judges of the Supreme Court are appointed based on specific criteria, ensuring that only qualified individuals are chosen. The judiciary also has a significant role in appointing judges to higher courts.

- Reforms and Accountability: The government has proposed measures to enhance accountability in the judiciary, reflecting an ongoing commitment to judicial integrity.

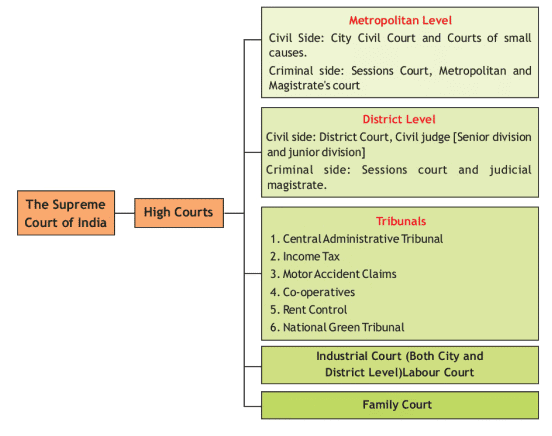

Structure and Hierarchy of Courts in India

Supreme Court: The Supreme Court is at the top of the Indian legal system. It has the authority to oversee and review the decisions made by High Courts and is the highest court in the country.

High Courts: Below the Supreme Court are the High Courts, which serve as the highest judicial authority in each state. High Courts have a long history, dating back to 1862 when they were established in Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras under the Indian High Court Act, 1861. Over time, more High Courts have been established in other states.

Jurisdiction of High Courts: The High Courts possess various types of jurisdiction:

- Original Jurisdiction: This allows High Courts to hear cases related to testamentary, matrimonial, and guardianship matters. Original jurisdiction is granted under different statutes.

- Extraordinary Jurisdiction: Under Article 226 of the Constitution, High Courts can issue various writs, exercising their extraordinary jurisdiction.

- Supervisory Power: High Courts have the authority to supervise subordinate courts within their jurisdiction.

- Contempt Powers: As courts of record, High Courts can punish for contempt of court, including contempt committed by subordinate courts.

Subordinate Courts: Below the High Courts are the subordinate courts, which include civil courts, family courts, criminal courts, and various district courts involved in the administration of justice. The structure of subordinate courts is generally similar across the country, with some variations.

Civil Courts: The lowest civil courts are Munsiff’s Courts, followed by Subordinate Judges. The District Judge hears appeals from Subordinate Judges and Munsiffs and has unlimited original jurisdiction in civil and criminal cases.

Criminal Courts: The District and Sessions Judge is the highest authority for criminal cases in the district. Criminal trials are conducted by Judicial Magistrates, with the Chief Judicial Magistrate overseeing criminal courts in a district. In metropolitan areas, there are Metropolitan Magistrates.

Appeals: Appeals from subordinate courts can be made to the High Court.

Appointment of Judges: District and Sessions Judges are appointed by the Governor in consultation with the High Court. To become a District Judge, a person usually needs at least seven years of legal experience and should not be in government service. Other judges in the subordinate judiciary are appointed by the Governor following specific rules, with input from the State Public Service Commission and the High Court.

The Civil Process and the Role of Civil Courts

The Code of Civil Procedure 1908 (CPC) is a set of rules that governs how civil courts operate in India. It does not create or take away any legal rights but simply regulates the procedure to be followed by these courts. Civil cases typically involve issues such as property disputes, business matters, personal domestic problems, and divorces, where an individual's constitutional and personal rights are at stake.The CPC outlines various aspects of civil litigation, including:

- Procedure for Filing a Civil Case: The steps and requirements for initiating a civil lawsuit.

- Court Powers: The authority of courts to issue different types of orders.

- Court Fees and Stamps: The costs involved in filing a case.

- Rights of Parties: The legal rights of plaintiffs and defendants in a case.

- Jurisdiction: The scope and limits of civil courts' authority.

- Specific Rules for Proceedings: Detailed guidelines for how cases should be conducted.

- Right of Appeals, Reviews, and References: The rights of parties to challenge or seek a review of court decisions.

The first uniform Code of Civil Procedure was introduced in 1859, and the current version was enacted in 1908 to consolidate and amend the laws related to civil procedure. The CPC aims to promote justice and is not meant for imposing punishments or penalties.

The CPC consists of two main parts:

- Main Body: Contains 158 sections that deal with general principles of jurisdiction.

- First Schedule: Contains 51 Orders and Rules related to the procedure and manner of exercising jurisdiction.

The sections in the main body are fundamental and can only be amended by the legislature, while the High Courts can amend the Orders and Rules in the First Schedule. The CPC does not have retrospective effect, meaning it applies only to cases filed after its enactment.

The Structure of Civil Courts

Disputes involving property, contract breaches, financial wrongs, minor omissions, etc., fall under the category of civil wrongs and are addressed through a civil process. In such instances, aggrieved individuals must initiate civil suits. Courts of law administer justice by evaluating the nature of the wrong committed. Civil wrongs are remedied in civil courts through injunctions or by awarding damages or compensation to the affected party.

Common Legal Terminologies

Some Common Terminologies:

- Plaintiff: The individual who initiates the civil case against another party.

- Defendant: The individual against whom the case is filed.

- Plaint: The document submitted by the plaintiff outlining their version of the case.

- Written Statement: The defendant's response to the plaint.

- Appellant: The person who files an appeal.

- Respondent: The party against whom the appeal is filed.

- Prosecution (Criminal): The victim's side in a criminal case who files the case.

- Defence: The side representing the accused in a criminal case.

- Application:. document seeking urgent relief, which can be filed by either party. It can be submitted with the plaint or written statement or during the proceedings. The person filing the application is called the applicant, and the person against whom it is filed is the respondent.

- Interim: Refers to actions taken during the proceedings.

- Arrested and Accused Person: An arrested person is someone taken into custody by the police based on suspicion of committing an offence. This does not imply conviction. Once sufficient evidence is gathered and a trial is initiated, the arrested person becomes an accused.

Types of Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction refers to the scope of a court's authority to hear and decide cases.- Territorial Jurisdiction: The geographical area within which a court has the authority to exercise its jurisdiction.

- Pecuniary Jurisdiction: Jurisdiction based on the monetary value of claims that a court can hear.

- Original Jurisdiction: The authority of a court to hear and decide a case for the first time.

- Appellate Jurisdiction: The power of a court to hear appeals from decisions made by lower courts.

- Jurisdiction as to Subject Matter: Jurisdiction defined by the types of cases a court can hear, such as family law, criminal law, etc.

Res sub judice and Res judicata in Code of Civil Procedure, 1908

- Res sub judice: Section 10 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, refers to the principle that if the same subject matter is under consideration in a court of law between the same parties, any other court is prohibited from entertaining a similar case until the first suit is resolved.

- Res judicata: Section 11 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, means a matter that has been decided. This doctrine prevents the trial of a subsequent suit on the same cause of action between the same parties. It is based on the finality of litigation and the conclusiveness of a decision, rooted in the principles of justice, equity, and good conscience.

Examples:

- If X sues Y for breach of contract and the suit is dismissed, X cannot file a suit for damages for breach of contract as it is barred by res judicata.

- If X files a suit for negligence against his employee Y and simultaneously files another suit for claiming accounts from Y, the second suit is stayed as it is res sub judice. Once the first suit is decided, the matters in the second suit would be res judicata based on the decision in the first suit.

Difference between Res Judicata and Res Sub-Judice

Res judicata pertains to matters that have already been decided, while res sub judice applies to matters that are currently pending in a court of law.

Structure and Functioning of Criminal Courts in India

Criminal justice in India is administered through Magistrate Courts and Sessions Courts.

- The Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC), along with other penal laws, forms the basis of India’s substantive criminal law. The IPC, influenced by English criminal law, has proven to be effective over time, but it requires enforcement to be applicable.

- Following the IPC, the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1861 was enacted. This code was later repealed, and the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) was introduced to facilitate the administration and enforcement of substantive criminal law. The CrPC also regulates the functioning of the machinery responsible for investigating and trying offences.

- Additionally, the Indian Evidence Act of 1872 was established to guide the processes of investigation and trial.

Categories of Criminal Courts in India

Courts of Session

- According to Section 9 of the CrPC, Courts of Session are established by the State Government for each sessions division.

- A Judge, appointed by the High Court of the respective state, presides over these courts.

- The High Court may also appoint Additional Sessions Judges and Assistant Sessions Judges to assist in these courts.

- Courts of Session have the authority to impose any sentence, including capital punishment.

Chief Judicial Magistrate and Additional Chief Judicial Magistrate

- In every district (excluding metropolitan areas), the High Court appoints a Judicial Magistrate of the First Class to serve as the Chief Judicial Magistrate.

- The Chief Judicial Magistrate can impose various sentences, except for:

- death sentences

- life imprisonment

- imprisonment for a term exceeding seven years

- The Chief Judicial Magistrate is subordinate to the Sessions Judge.

- Other Judicial Magistrates are also subordinate to the Chief Judicial Magistrate, under the general control of the Sessions Judge.

Courts of Judicial Magistrates

- Section 11 of the CrPC mandates the establishment of Courts of Judicial Magistrates in every district (excluding metropolitan areas), as specified by the State Government in consultation with the High Court.

- Judicial Magistrates of the First Class are the second lowest level in the Criminal Court hierarchy in India.

- They are under the general control of the Sessions Judge and subordinate to the Chief Judicial Magistrate.

- Section 29 of the CrPC allows a Judicial Magistrate of the First Class to impose a sentence of imprisonment for up to three years, a fine not exceeding 10,000 rupees, or both.

- The Judicial Magistrate of the Second Class is the lowest level court, competent to try cases with offences punishable by imprisonment for up to one year, fines up to 5,000 rupees, or both.

- The Chief Judicial Magistrate can impose fines and prison sentences up to seven years.

- The Assistant Sessions Judge can impose punishments up to ten years imprisonment and any fine.

- The Sessions Judge can impose any punishment authorized by law, subject to confirmation by the High Court for death sentences.

Metropolitan Magistrates

- Courts of Metropolitan Magistrates were established under Section 16 of the CrPC.

- The Chief Metropolitan Magistrate and Additional Chief Metropolitan Magistrates were created by Section 17 of the CrPC.

- Special Metropolitan Magistrates were also provided for under the same Code.

- Towns with populations exceeding one million can be designated as Metropolitan Areas, where these magistrates operate.

- Metropolitan magistrates are under the general control of the Sessions Judge and are subordinate to the Chief Metropolitan Magistrate.

Executive Magistrates

- The State Government can appoint Executive Magistrates in every district and metropolitan area as needed, designating one as the District Magistrate.

- Executive Magistrates, part of the executive branch, collaborate with the police to maintain law and order and perform certain judicial functions.

- Their responsibilities include traffic violations, document registrations (such as sale deeds, wills, marriage certificates, and birth and death certificates).

- They are commonly known as District Magistrates (DM), Sub Divisional Magistrates (SDM), executive magistrates, and special executive magistrates.

Types of Offences

Bailable and Non-bailable Offences

- The term “bail” is not defined in the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), but “bailable” and “non-bailable” offences are clearly defined. The main purpose of detaining an accused is to ensure their presence at trial and sentencing if found guilty. The decision to grant bail is up to the judiciary.

- The Supreme Court of India has clarified that bail includes release on one’s own bond, with or without sureties.

- The CrPC categorizes offences as “bailable” or “non-bailable.” Generally, serious offences punishable by three years or more of imprisonment are considered non-bailable. However, this rule can be adjusted based on specific circumstances.

- An accused person has the right to be released on bail if arrested for a bailable offence without a warrant (Section 436 of CrPC). In contrast, non-bailable offences do not guarantee bail; it is at the court’s discretion.

- Only the court that granted bail has the authority to cancel it; police officers do not have this power.

Anticipatory Bail

Section 438 of the CrPC allows superior courts to grant anticipatory bail. This type of bail can be requested when a person has a valid reason to believe that they may be arrested. Applications for anticipatory bail can be made to the Sessions Court, the High Court, or even the Supreme Court. However, it is usually expected that the Court of Sessions will be approached first for such requests.

When considering an application for anticipatory bail, the court may take into account several factors, including:

- The nature and seriousness of the accusation

- The applicant's previous criminal record (antecedents)

- The likelihood of the accused fleeing from justice

- Whether the accusation seems to be aimed at humiliating the applicant

Cognizable and Non-Cognizable Offences in CrPC

- Cognizable offences are serious crimes where the police can arrest without a warrant and start an investigation without prior approval. Examples include murder, robbery, dacoity, rape, and kidnapping. These offences are considered serious because they carry a minimum punishment of three years imprisonment, as indicated in the First Schedule of the CrPC.

- Non-cognizable offences are less serious crimes where the police cannot arrest without a warrant and need permission to start an investigation. For instance, bigamy, which is punishable by more than five years imprisonment, falls under this category despite its severity.

The distinction between cognizable and non-cognizable offences is crucial as it determines the procedure for arrest and investigation. Cognizable offences require immediate action, while non-cognizable offences involve a more formal process with a warrant for arrest.

Compoundable and Non-Compoundable Offences

- Compoundable Offences are those where the State and the accused can reach an agreement to settle the matter by paying a fine instead of facing imprisonment. A typical example of this is when someone is caught travelling without a ticket on a bus or train; the officer issuing the fine is essentially compounding the offence.

- Non-Compoundable Offences, on the other hand, are serious crimes where such an arrangement is not acceptable. For instance, it would not be appropriate for murderers to compound their offences.

Criminal Investigation and First Information Report (FIR)

- FIR stands for First Information Report. It is a report made by a police officer based on information received about a cognizable offence, either from the victim or another person.

- The purpose of the FIR is to initiate the criminal process. The police cannot refuse to register an FIR. If they do, the aggrieved person can complain to the Superintendent of Police.

- An FIR can be filed in the police station where the offence occurred, either in writing or verbally. The police officer must record it in writing and get the informant's signature.

- Section 154 of the CrPC outlines how such information should be recorded. Key points include:

- Any person can inform the police about a cognizable offence.

- An FIR is not evidence by itself; it needs to be proven and can be used as relevant fact.

- Police must record the information in writing, obtain the informant's signature, and read the contents to them.

- Police must give a copy of the information to the informant and send the original FIR to the Magistrate.

- If a police officer refuses to register an FIR, the aggrieved person can send the information to the Superintendent of Police.

- An FIR should be made soon after an incident while it is still fresh in the informant's memory.

- Telephonic information about a cognizable offence can also constitute an FIR.

- The Government has introduced Zero FIR provisions allowing victims to file complaints in any police station for prompt action, with subsequent transfer to the appropriate station.

Information to the Police Regarding Non-Cognizable Offences

According to Section 155 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), when a person informs the officer in charge of a police station about a non-cognizable offence, the officer is required to record the substance of this information in a designated book.

- The police officer does not have any further obligation unless a magistrate directs them to investigate the case.

- Non-cognizable offences are generally viewed as private criminal wrongs, and the principle is that no police officer should investigate such a case without the order of a magistrate who has the authority to try the case or send it for trial.

- However, if a criminal case involves both cognizable and non-cognizable offences, the entire case is considered cognizable, regardless of the presence of non-cognizable offences.

Arrest and Rights of the Arrested Person

Production Before Magistrate:

- According to Section 57/167 of the CrPC, an accused individual must be presented before a Magistrate within 24 hours of their arrest.

- If the investigation cannot be completed within this timeframe, a Magistrate may authorize the remand of the arrested person to police custody under Section 167(3) of the CrPC.

- The Magistrate must be convinced that there are valid grounds for remanding the accused to police custody.

Information of Offence:

- Under Section 50 of the CrPC, the arrested person has the right to be informed about the details of the offence or the grounds for their arrest.

- If arrested without a warrant for a bailable offence, the person must be informed of their entitlement to be released on bail.

Right to Inform:

- According to Section 50A of the CrPC, the arrested person has the right to have a nominated individual informed about their arrest.

- The Magistrate is obligated to ensure compliance with this provision.

- The Supreme Court has recognized the right to legal counsel for the arrested person in cases such as Nandini Satpathy and DK Basu.

Personal Search:

- Under Section 51 of the CrPC, a person who is arrested may be searched, and a list of any articles found on their person must be prepared.

- This personal search memo is crucial, especially if there are allegations of recovering incriminating materials from the accused.

Medical Examination:

- Under Section 54 of the CrPC, the arrested person can request a medical examination to disprove their involvement in the offence or to prove an offence against their body by another person.

- Sections 53 and 53A of the CrPC allow the police to send the arrested person for a medical examination.

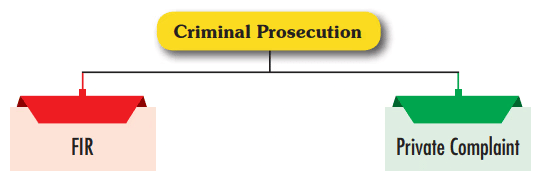

Criminal Process: Investigation and Prosecution

Criminal prosecution in India generally follows two main streams:

(i) Cases initiated based on police reports or First Information Reports (FIRs).

(ii) Cases initiated through private complaints.

Criminal Prosecution

(i) Police Report/FIR Cases:

- Prosecution is conducted by the Director of Public Prosecution through public prosecutors.

- Section 225 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) mandates that every trial before a Sessions Court be conducted by a public prosecutor.

(ii) Private Complaint Cases:

- Private parties can conduct cases through their own lawyers.

- An example is a private complaint under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881.

- A "private complaint" refers to a complaint filed directly by the complainant in court.

Cognizance by Magistrate:

- The Magistrate has the authority to take cognizance of private complaints under Section 190(1)(a) of the CrPC.

Stages of Criminal Procedure

The CrPC outlines the procedure for investigation, inquiry, and trial for offences under the Indian Penal Code or any other law.

(i) Investigation:

- The objective is to collect evidence for any inquiry or trial.

- Initiated by the police after recording an FIR.

- Involves ascertaining facts and circumstances of the case, including:

- Collection of evidence, inspection of the crime scene, ascertainment of facts, discovery of articles used in the crime, arrest of suspects, interrogation and examination of individuals, search and seizure of relevant items.

- Ends with a police report to the Magistrate.

(ii) Inquiry:

- The second stage where a Magistrate determines whether to commit the accused to Sessions Court or discharge them.

- Defined in Section 2(g) of the CrPC as an inquiry conducted by a Magistrate or Court, excluding a trial.

- Involves proceedings before a Magistrate prior to charge framing, not resulting in conviction.

(iii) Trial:

- Judicial determination of a person’s guilt or innocence.

- Involves examination and determination of the case by a judicial tribunal, ending in conviction or acquittal.

- Based on the adversary system and accusatorial method, where the prosecutor accuses the defendant and must prove the case beyond reasonable doubt.

- Presumption of innocence until proven guilty is a fundamental principle.

Key Stages in a Criminal Case

(i) Investigation Stage:

- Initiated by a Police officer based on their own findings or under the direction of a Magistrate.

- If no offence is found, the Police officer reports to the Magistrate, who may drop the proceedings.

- If the Magistrate believes an offence has occurred, the case moves forward for further inquiry.

(ii) Inquiry Stage:

- Conducted by a Magistrate to determine whether there is sufficient evidence to proceed with the case.

- If no prima facie case is established, the complaint is dismissed or the accused is discharged.

- If a prima facie case is found, charges are framed against the accused.

(iii) Trial Stage:

- Begins when charges are framed against the accused.

- The trial may be conducted by the Magistrate or referred to a Sessions Court for serious offences.

- The Magistrate or court determines the guilt or innocence of the accused, leading to a conviction or acquittal.

Warrant, Summons, and Summary Trials

The Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) classifies criminal trials into two main types: warrant cases and summons cases.

1. Warrant Cases

- Warrant cases involve serious offences punishable by death, life imprisonment, or imprisonment for more than two years.

- There are two procedures for trying warrant cases by a Magistrate:

- Cases instituted on a Police report (Sections 238-243)

- Cases instituted otherwise than on a Police report, such as complaints (Sections 238-243)

- A warrant case, as per Section 2(x) of the CrPC, pertains to offences punishable by death, life imprisonment, or imprisonment exceeding two years.

- In cases based on a Police report, the Magistrate can discharge the accused if the report and documents do not provide a legal basis for the case.

- In cases not based on a Police report, the Magistrate hears the prosecution and takes evidence. If there is no case, the accused is discharged. If not, a regular trial follows.

- For offences punishable by death, life imprisonment, or imprisonment exceeding seven years, the trial is conducted in a Sessions Court after being committed or forwarded by a Magistrate.

2. Summons Cases

- A summons case refers to offences not considered warrant cases, specifically those punishable by imprisonment not exceeding two years.

- In summons cases, there is no need to frame a charge. The court provides a notice of the accusation to the accused when they appear in response to the summons.

- The court can convert a summons case into a warrant case if deemed necessary for justice.

3. Summary Trials

- Summary trials are expedited and simplified procedures for disposing of cases quickly.

- Only minor offences are tried in summary trials, while complex cases are reserved for summons or warrant trials.

- Sections 260 to 265 of the CrPC outline the provisions for summary hearings.

Stages of a Criminal Trial

A criminal trial consists of several distinct stages:

1. Framing of Charge or Issuance of Notice:

- This stage marks the beginning of a trial where the judge assesses the evidence to determine if there is a prima facie case against the accused.

- If the evidence suggests the commission of an offence, the charge is framed, and the trial proceeds.

- If not, the accused is discharged, and reasons are recorded.

- The charge is read and explained to the accused, who is then asked to plead guilty or claim to be tried.

2. Recording of Prosecution Evidence:

- After framing the charge, the prosecution presents its witnesses, and their statements are taken under oath (examination-in-chief).

- The accused has the right to cross-examine all prosecution witnesses.

- Section 309 of the CrPC mandates expeditious proceedings, with witness examination continuing day-to-day once it begins.

3. Statement of Accused:

- The court can examine the accused at any stage of the inquiry or trial to elicit explanations for incriminating circumstances.

- However, it is mandatory to question the accused after examining prosecution evidence that incriminates them.

- This examination is without oath and provides the accused an opportunity to explain the incriminating facts and circumstances.

4. Defence Evidence:

- If the judge finds no evidence of the accused's guilt after considering prosecution evidence, examining the accused, and hearing both sides, an acquittal is recorded.

- If not acquitted for lack of evidence, the accused must present a defence and supporting evidence.

- The accused can produce witnesses willing to testify in support of the defence and can also testify on their behalf.

- The accused may request the attendance of witnesses or production of documents or things.

- Witnesses produced by the accused are cross-examined by the prosecution.

- The accused has the right to present evidence after their statement is recorded if they wish.

Steps of Criminal Trial in India

I. Pre-Trial Stage

The pre-trial stage involves the following steps:

1. Registration of FIR:. First Information Report (FIR) is registered when the police receive information about the commission of a cognizable offence.

2. Investigation: The police investigate the matter, collect evidence, and record statements of witnesses.

3. Charge Sheet: If the police find sufficient evidence, they file a charge sheet in court, detailing the offences and evidence against the accused.

4. Cognizance by Magistrate: The magistrate takes cognizance of the offence based on the charge sheet.

5. Framing of Charges: The accused is brought before the court, and charges are framed against them. They can plead guilty or not guilty at this stage.

6. Bail: The court decides on the bail application of the accused.

II. Trial Stage

The trial stage includes the following steps:

1. Examination-in-Chief: The prosecution witnesses are examined, and their statements are recorded.

2. Cross-Examination: The defence has the right to cross-examine the prosecution witnesses to challenge their credibility.

3. Defence Evidence: The accused can present their defence evidence, including witnesses and documents.

4. Final Arguments: The prosecution and defence present their final arguments summarizing the evidence and legal positions.

5. Judgment: The judge delivers the judgment based on the evidence and arguments presented.

III. Post-Trial Stage

1. Acquittal: If the accused is found not guilty, they are acquitted, and the case is closed.

2. Conviction: If convicted, the court proceeds to sentencing.

3. Appeal: The accused has the right to appeal against the conviction and sentence in a higher court.

4. Revision: The higher court can revise the order of the lower court in certain circumstances.

5. Review: The Supreme Court can review its own judgments under Article 137 of the Constitution.

6. SLP: Special Leave Petition can be filed in the Supreme Court against any order of the High Court.

7. Compounding: Certain offences can be compounded, i.e., parties can reach a compromise and seek to quash the proceedings.

Age and Criminal Liability

Whether Liable

- Up to 7 years: No criminal liability.

- 7-12 years: The mental agility of the child is assessed.

- 12-16 years:. child is liable under the Juvenile Justice Act.

- 16-18 years:. child is liable under the Juvenile Justice Act. However, if the crime is heinous, the child can be tried as an adult under the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and other criminal laws.

- Above 18 years: Criminally liable under the IPC and other criminal laws.

Doctrine of Autrefois Acquit and Autrefois Convict

The doctrine of autrefois acquit and auterfois convict is a legal principle that prevents a person from being tried again for the same offence or on the same facts for any other offence, if they have already been acquitted or convicted. This principle is enshrined in Article 20(2) of the Constitution of India and Section 300 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC).Right Against Self-Incrimination

- The right against self-incrimination is guaranteed under Article 20(3) of the Constitution of India. It protects an accused person from being compelled to be a witness against themselves.

- However, there are certain restrictions on the exercise of this right:

- Only documents or statements that are within the personal knowledge of the accused are protected. Documents maintained as part of a statutory requirement may not be protected.

- The accused can be required to provide samples such as handwriting, blood, or DNA, as these are not considered part of their personal knowledge.

- Article 20(3) protects the accused from being compelled to produce documents. However, a search and seizure does not constitute compulsion to produce and is therefore not covered by this protection.

- Summons under Section 91 of the CrPC cannot be issued to an accused person. However, a general search warrant under Section 93(1)(c) of the CrPC is not protected by Article 20(3) of the Constitution.

Function and Role of Police

The police are one of the most visible and present organizations in society, acting as representatives of the government. In times of need, danger, or crisis, people turn to the police for help and guidance. The police are expected to be accessible, interactive, and dynamic, with a wide range of duties that are both varied and complex.Broad Roles of Police

- Maintenance of Law: Upholding and enforcing the law fairly, protecting the life and liberty of the public.

- Maintenance of Order: Ensuring public order and safety.

Specific Roles and Functions of Police

- Internal Security: Protecting against terrorist activities, communal disturbances, and militant threats.

- Public Protection: Safeguarding the public from vandalism, violence, and attacks.

- Crime Prevention: Reducing opportunities for crime through preventive measures and cooperation with other agencies.

- Complaint Registration: Accurately registering all complaints and investigating cognizable offenses.

- Community Security: Creating and maintaining a sense of security within the community.

- Disaster Response: Providing assistance as first responders in natural or man-made disasters.

- Intelligence Gathering: Collecting and disseminating intelligence related to public peace, social offenses, and national security.

- Unclaimed Property: Taking charge of and managing unclaimed property according to prescribed procedures.

- Police Welfare: Training, motivating, and ensuring the welfare of police personnel.

The police force operates under the State Government and falls within the Executive realm. The structure and function of the police are outlined in the Police Act of 1861.

Other Courts in India

Besides the civil and criminal courts mentioned earlier, India has several special courts and tribunals dedicated to specific areas of law. These include:

- Motor Accidents Claims Tribunal (MACT): Handles claims related to motor vehicle accidents.

- Rent Control Tribunal: Deals with disputes related to rent control and tenancy issues.

- Railway Claims Tribunal: Addresses claims related to railway accidents and passenger grievances.

- Debt Recovery Tribunal (DRT): Focuses on the recovery of debts owed to banks and financial institutions.

- Central Excise and Service Tax Appellate Tribunal (CESTAT): Hears appeals related to central excise and service tax matters.

- Income Tax Appellate Tribunal (ITAT): Resolves disputes related to income tax assessments and appeals.

- National Green Tribunal (NGT): Deals with environmental protection and conservation issues.

Purpose of Special Courts

- These special courts aim to enhance judicial efficiency by reducing the case burden on traditional courts.

- They provide quicker relief to parties involved in specific legal matters, ensuring timely justice.

Family Courts in India

Jurisdiction:Family Courts in India handle a range of matrimonial issues, including:- Nullity of marriage

- Judicial separation

- Divorce

- Restitution of conjugal rights

- Declaration of marriage validity and matrimonial status

- Property disputes between spouses

- Legitimacy declarations

- Guardianship and custody of minors

- Maintenance issues, including cases under the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC)

- Family Courts Act, 1984: Enacted on September 14, 1984, the Family Courts Act aims to promote conciliation and ensure speedy resolution of disputes related to marriage and family affairs. The Act seeks to shift family and marital disputes from the crowded and intimidating environment of traditional courts to more congenial and sympathetic settings. The focus is on 'conciliation' rather than 'confrontation,' emphasizing a non-adversarial approach to resolving family disputes.

- Legal Representation: The Act generally restricts parties from being represented by lawyers without the court's permission. However, courts typically grant this permission, and lawyers often represent the parties in Family Court proceedings.

- Conciliation Process:. unique feature of Family Court proceedings is the emphasis on conciliation. Cases are initially referred to conciliation, and only if these efforts fail to resolve the issue, the matter is taken up for trial by the court. Conciliators, who are professionals appointed by the court, facilitate this process.

- Appeals: Once a final order is issued by the Family Court, the aggrieved party has the option to file an appeal before the High Court. Such appeals are heard by a bench of two judges.

Administrative Tribunals

- To reduce the backlog of pending cases in various High Courts and other courts across the country, Parliament enacted the Administrative Tribunals Act in 1985, which came into effect in July of the same year. Central Administrative Tribunals were set up in November 1985 in cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Calcutta, and Allahabad. Currently, there are 17 Benches of the Tribunal located throughout the country, with 33 Division Benches. Additionally, circuit sittings are held in various locations, including Nagpur, Goa, Aurangabad, Jammu, Shimla, Indore, Gwalior, Bilaspur, Ranchi, Pondicherry, Gangtok, Port Blair, Shillong, Agartala, Kohima, Imphal, Itanagar, Aizwal, and Nainital.

- The Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT) was established to resolve disputes related to the recruitment and service conditions of individuals appointed to public services and positions connected with the affairs of the Union or local authorities within India or under the control of the Government of India. This tribunal also addresses matters related to these issues. Article 323 A, added by the 42nd amendment of the Constitution of India, governs the functioning of the CAT. The conditions of service for the Chairman, Vice-Chairmen, and Members of the CAT are regulated by the Central Administrative Tribunal (Salaries and Allowances and Conditions of Service of Chairman, Vice-Chairmen and Members) Rules, 1985, which have been amended over time.

|

69 videos|80 docs|25 tests

|

FAQs on Judiciary - Constitutional, Civil and Criminal Courts and Processes Chapter Notes - Legal Studies for Class 11 - Humanities/Arts

| 1. What is the role of the judiciary in India as per the Constitution? |  |

| 2. What are the main functions of civil courts in India? |  |

| 3. How are criminal courts structured in India? |  |

| 4. What is the significance of impartiality in the Indian judiciary? |  |

| 5. What are the other types of courts in India apart from civil and criminal courts? |  |