Higher Order Thinking Skills - Liberalisation, Privatisation and Globalisation : An Appraisal | Economics Class 12 - Commerce PDF Download

Q1: Compare the outcomes of disinvestment in PSUs (e.g., Navratnas) with the original objectives stated by the government. Do you think disinvestment has achieved its goals? Justify your answer.

Ans:

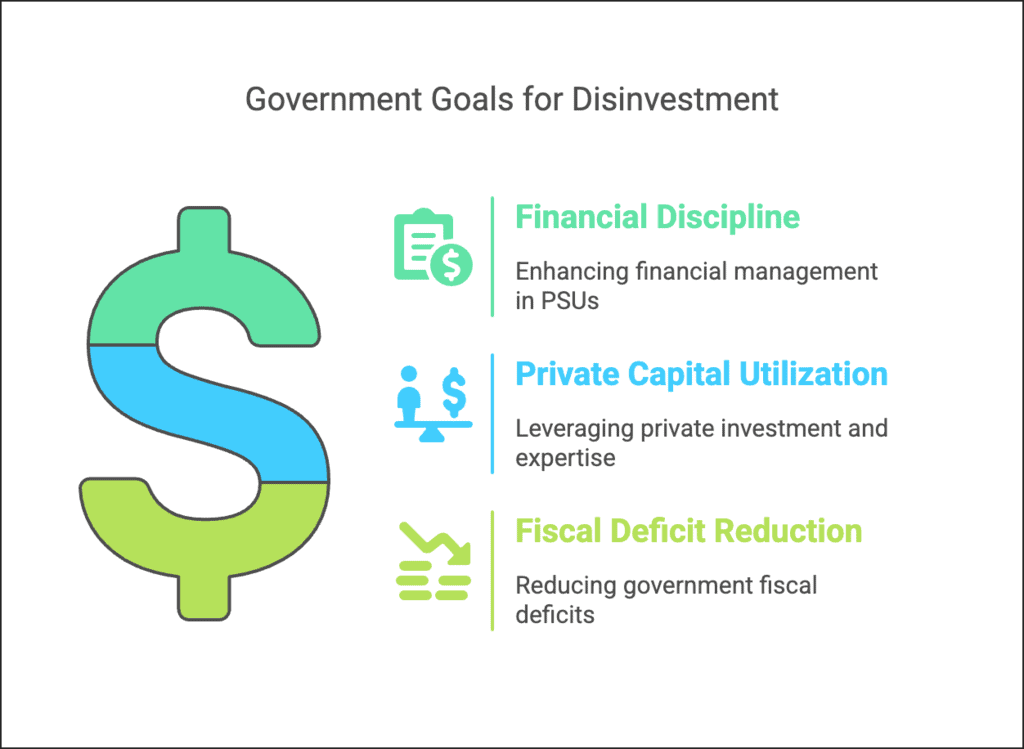

Government Objectives for Disinvestment

- Improve financial discipline and modernise PSUs.

- Utilise private capital and management expertise.

- Reduce fiscal deficits and enhance competitiveness.

Outcomes of Disinvestment

- Targets Met: Achieved ₹1,00,057 crore in 2017-18, exceeding initial goals (e.g., 1991-92: ₹3,040 crore).

- Partial Modernisation: Navratnas like ONGC Videsh and Tata Steel expanded globally (e.g., ONGC projects in 16 countries).

Criticisms

- Undervalued Sales: Assets sold below market value, causing revenue loss.

- Fund Misuse: Proceeds used to plug fiscal gaps, not PSU development or social infrastructure.

- Sectoral Flaws: Industrial growth declined post-2002 (Table 3.1: 7.4% in 2014-15 vs. 9.4% in 2002-07), with limited employment generation.

Goal Achievement Analysis

Successes: Short-term fiscal stability, global expansion of select PSUs.

Failures:

- No sustainable industrial growth; sectors like agriculture stagnated (1.5% growth in 2012-13).

- Social welfare was compromised (e.g., the Sircilla tragedy due to power tariff hikes).

- Tax reforms and GST failed to boost revenues significantly, affecting public spending.

Q2: Evaluate the reasons behind India's economic crisis in 1991. How did the inefficiencies in fiscal management during the 1980s contribute to the balance of payments crisis?

Ans: Evaluation of India's 1991 Economic Crisis and Fiscal Mismanagement in the 1980s:

1. Fiscal Profligacy and Borrowing:

- During the 1980s, India’s fiscal policies were marked by unsustainable spending.

- The government prioritized welfare schemes, subsidies, and public sector expansion but failed to bolster revenue through effective taxation or public sector reforms.

- Persistent fiscal deficits—averaging 8-9% of GDP—were financed through domestic borrowing (leading to high inflation) and external loans.

- Crucially, borrowed funds were diverted to unproductive expenditures like consumption subsidies rather than infrastructure or export-oriented industries.

- This eroded fiscal stability and increased external debt, which tripled from 20 billion (1980) to 72 billion (1991).

2. Trade Imbalances and External Shocks:

- Protectionist trade policies stifled export growth.

- High tariffs, import licensing, and a focus on inward-oriented industries made Indian goods uncompetitive globally.

- Exports stagnated at 5-6% of GDP, while imports surged due to rising oil prices after the Gulf War (1990-91).

- The current account deficit ballooned to 3.5% of GDP by 1990.

- Foreign exchange reserves plummeted to $1.2 billion (June 1991), insufficient to cover even three weeks of imports, triggering a liquidity crisis.

3. Structural Inefficiencies:

- Strict rules like industrial licensing, price controls, and special protections for small businesses limited the ability of the private sector to innovate and improve productivity.

- Public sector enterprises (PSEs) faced many problems and became a burden on finances due to their inefficiencies.

- The lack of growth in agriculture further restricted income increases, which in turn lowered the demand for goods and services within the country.

4. Balance of Payments Crisis:

- By 1991, India faced a perfect storm: dwindling forex reserves, inability to service external debt, and loss of investor confidence.

- Global lenders halted credit, forcing India to pledge gold reserves and seek a $7 billion IMF bailout.

- The conditionalities imposed—liberalisation, privatisation, and globalisation—highlighted how decades of fiscal indiscipline, trade rigidities, and structural bottlenecks culminated in the crisis.

Q3: Liberalisation aimed to remove restrictions and promote competition. Analyse how the deregulation of the industrial sector might have impacted small-scale industries in India post-1991.

Ans: Analysis of Deregulation’s Impact on Small-Scale Industries (SSIs) Post-1991:

1. Increased Competition and Market Challenges:

- Deregulation abolished industrial licensing and dereserved numerous products previously exclusive to SSIs.

- Large domestic firms and multinational corporations (MNCs) entered these sectors, leveraging economies of scale, advanced technology, and better access to capital.

- SSIs, constrained by limited resources and outdated production methods, struggled to compete.

- For instance, sectors like textiles, toys, and leather goods saw SSIs lose market share to larger players, leading to closures or downsizing.

2. Loss of Protective Reservations:

- Pre-1991, over 800 products were reserved for SSIs, ensuring market monopolies.

- Post-reforms, dereservation exposed SSIs to open competition.

- Many units, unable to match the cost efficiency or quality standards of larger firms, faced declining profitability.

- This was exacerbated by the removal of subsidies and reduced government support, forcing SSIs to operate in a market-driven environment without safety nets.

3. Access to Technology and Capital:

- While deregulation aimed to modernize industries, SSIs often lacked access to formal credit and technology upgrades.

- Financial sector reforms prioritized commercial viability, making banks hesitant to lend to small enterprises with perceived higher risks.

- Consequently, many SSIs remained trapped in low-productivity cycles, unable to adopt automation or improve quality to meet global standards.

4. Export Opportunities and Globalization:

- Trade liberalization opened export markets for SSIs in sectors like handicrafts, garments, and agro-processing.

- Some units integrated into global supply chains, benefiting from outsourcing trends.

- However, success required compliance with international quality norms and scaling production—challenges for undercapitalized SSIs.

- Only a minority with access to networks or cooperative models thrived.

5. Employment and Socioeconomic Impact:

- SSIs are labour-intensive, contributing significantly to rural and semi-urban employment.

- Deregulation-induced closures led to job losses in traditional sectors, worsening informal labour conditions.

- Conversely, surviving SSIs that modernized created higher-skilled jobs, though such cases were limited.

Q4: Imagine you were an economic advisor to the Indian government in 1991. Propose an alternative strategy to address the balance of payments crisis without relying heavily on IMF and World Bank loans. Justify your approach with reference to India's economic conditions at the time.

Ans: Alternative Strategy to Address the 1991 Balance of Payments Crisis Without Heavy Reliance on IMF/World Bank Loans:

1. Aggressive Domestic Resource Mobilisation:

- Gold Bonds and NRI Deposits: Launch a sovereign gold bond scheme to incentivise citizens to deposit gold with the government in exchange for interest-bearing bonds. This could replicate the success of the 1991 gold pledge but without physical collateralisation abroad. Simultaneously, offer higher interest rates on NRI deposits to attract forex inflows, leveraging the Indian diaspora’s financial ties.

- Rationalise Subsidies: Phase out non-essential subsidies (e.g., fertilisers, luxury goods) and redirect funds to critical sectors like agriculture and exports. This would reduce fiscal deficits and free up resources for debt servicing.

2. Export-Led Growth and Trade Reforms:

- Controlled Devaluation: Implement a phased rupee devaluation to boost export competitiveness while avoiding inflationary shocks. Pair this with tax rebates and streamlined export procedures to incentivize sectors like textiles, gems, and software services.

- Temporary Import Compression: Impose higher tariffs on non-essential imports (e.g., consumer electronics) and promote import substitution in critical areas (e.g., pharmaceuticals, machinery). This would conserve forex for essential imports like oil and raw materials.

3. Debt Restructuring and Creditor Negotiations:

Bilateral Debt Rescheduling: Engage major creditors (e.g., Japan, USSR) to restructure external debt repayment timelines, citing geopolitical alliances and mutual trade interests. Offer stakes in public sector enterprises as collateral to secure creditor confidence.

4. Public Sector Reforms:

- Operational Autonomy: Grant greater managerial autonomy to profitable PSUs (e.g., ONGC, Indian Oil) to improve efficiency and attract joint ventures with foreign firms. Use their profits to offset fiscal gaps.

- Partial Disinvestment: Sell minority stakes in non-strategic PSUs to domestic investors and NRIs, generating revenue without ceding control.

5. Attract FDI Through Policy Certainty:

Fast-Track Approvals: Create a single-window clearance system for FDI in export-oriented industries (e.g., electronics and textiles) to bypass bureaucratic delays. Offer tax holidays and infrastructure support to build investor confidence.

Justification:

India’s 1991 crisis stemmed from fiscal indiscipline, low exports, and inefficient PSUs. This strategy addresses these root causes:

- Fiscal Consolidation: Cutting subsidies and mobilizing domestic savings reduces reliance on borrowing.

- Forex Stability: NRI deposits and gold bonds directly bolster reserves, while export promotion and import controls improve the trade balance.

- Structural Reforms: PSU autonomy and FDI incentives enhance productivity without full privatization, aligning with India’s mixed-economy ethos.

Challenges:

- Political resistance to subsidy cuts and devaluation.

- Risk of inflation from rupee depreciation.

- Creditors may demand stricter terms without IMF backing.

Conclusion:

This approach prioritizes self-reliance, leveraging India’s domestic savings, diaspora networks, and strategic sectoral reforms to stabilize the economy. While challenging, it offers a path to crisis resolution without surrendering policy autonomy to external agencies.

|

64 videos|308 docs|51 tests

|

FAQs on Higher Order Thinking Skills - Liberalisation, Privatisation and Globalisation : An Appraisal - Economics Class 12 - Commerce

| 1. What are the key differences between liberalisation, privatisation, and globalisation? |  |

| 2. How has liberalisation impacted economic growth in developing countries? |  |

| 3. What role does privatisation play in enhancing the efficiency of public services? |  |

| 4. How does globalisation affect local cultures and economies? |  |

| 5. What are the potential downsides of liberalisation and globalisation? |  |