Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 - Commerce PDF Download

Introduction

- Negotiable Instrument: Negotiable instrument is a type of document that ensures the payment of a certain amount of money, either on demand or at a specified time. It is a legal tool used in financial transactions to facilitate the transfer of money from one party to another.

- Before the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 (NI Act) was implemented, India followed the English Negotiable Instruments Act to regulate negotiable instruments.

- A negotiable instrument is essentially a document that promises the payment of money, either on demand or at a specific time, and it can take different forms based on the applicable laws in a country. The NI Act primarily deals with three types of instruments: bills of exchange, promissory notes, and cheques.

- In addition to these traditional instruments, modern payment methods like NEFT (National Electronic Fund Transfer) and RTGS (Real Time Gross Settlement) have also become popular modes of payment.

- This article aims to explore all aspects of the NI Act, 1881, which came into effect on March 1, 1882, and is applicable throughout India.

Objectives of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881

The main goal of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, is to strengthen and legalize the system governing negotiable instruments. This ensures that one person can transfer an instrument and pay a specific amount of money to another through negotiation. The Act aims to provide a clear and orderly set of rules regarding negotiable instruments, facilitating smooth financial transactions.

Composition of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881

The Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, consists of 148 sections organized into 17 chapters. It defines and amends the law related to negotiable instruments. Here is the composition of the Act:

- Chapter I (Sections 1 – 3): Preliminary provisions.

- Chapter II (Sections 4 – 25): Covers notes, bills, and cheques.

- Chapter III (Sections 26 – 45A): Discusses parties involved in notes, bills, and cheques.

- Chapter IV (Sections 46 – 60): Focuses on negotiation of instruments.

- Chapter V (Sections 61 – 77): Deals with presentment of instruments.

- Chapter VI (Sections 78 – 81): Covers payment and interest related to instruments.

- Chapter VII (Sections 82 – 90): Discusses discharge from liability of notes, bills, and cheques.

- Chapter VIII (Sections 91 – 98): Covers notice of dishonor.

- Chapter IX (Sections 99 – 104A): Discusses noting and protest of instruments.

- Chapter X (Sections 105 – 107): Deals with reasonable time for various actions.

- Chapter XI (Sections 108 – 116): Covers acceptance and payment for honor and reference in case of need.

- Chapter XII (Section 117): Discusses compensation related to instruments.

- Chapter XIII (Sections 118 – 122): Covers special rules of evidence related to instruments.

- Chapter XIV (Sections 123 – 131A): Discusses crossed cheques.

- Chapter XV (Sections 132 – 133): Covers bills in sets.

- Chapter XVI (Sections 134 – 137): Deals with international law related to instruments.

- Chapter XVII (Sections 138 – 148): Discusses penalties for dishonor of certain cheques due to insufficient funds.

Understanding Negotiation of Instruments

Negotiation of an instrument, as defined in Section 14 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, refers to the transfer of a negotiable instrument to another person, making them the "holder" of the instrument. For a valid negotiation, two conditions must be met:

- Transferability: The instrument must be transferable to another person.

- Vesting of Holder's Rights: The transferee must acquire the rights of the holder when the instrument is transferred.

Modes of Negotiating an Instrument

- By Delivery (Section 47): An instrument may be negotiated by delivery when it is payable to a bearer. For instance, if C, the holder of a bearer instrument, delivers it to A's agent for safekeeping, the instrument is negotiated by delivery.

- By Endorsement (Section 48):. negotiable instrument can be negotiated by endorsement when the maker signs the instrument, thereby endorsing and negotiating it.

Who May Negotiate an Instrument

- According to Section 51 of the Act, individuals such as the maker, drawer, holder, payee, or joint makers or payees can endorse or negotiate an instrument. However, they must not be restricted from doing so under Section 50 of the Act.

Negotiable Instruments

A negotiable instrument is a written document that represents a right in favor of an individual and can be freely transferred from one party to another. The term "negotiable" means that the instrument can be transferred for value and in good faith, allowing the new party to sue in their own name. While the term is not explicitly defined in the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, Section 13 provides an inclusive definition, including bills of exchange, promissory notes, and cheques that are payable on order or otherwise.

The key difference between a negotiable instrument and other documents is that the transferee of a negotiable instrument acquires a good title in good faith and for consideration, even if the transferor's title is flawed. In contrast, the transferee of other documents receives no better title than the transferor.

Meaning of a Negotiable Instrument

- A negotiable instrument is a document that is typically transferable from one person to another, as outlined in Section 13(1) of the Act.

- Examples of negotiable instruments include promissory notes, cheques, and bills of exchange.

- According to Justice Willis, a negotiable instrument is defined as one where the property is acquired by anyone who takes it in good faith and for value, regardless of any defects in the title of the person from whom it was obtained.

Conditions for Negotiability

- Freely Transferable: The instrument must be capable of being transferred freely, either by delivery or endorsement, from the true owner to another party.

- Defect in Title: The transferee should not be affected by any defects in the transferor's title.

- Capacity to Sue: The transferee must have the capacity to sue in their own name.

Common Traits of Negotiable Instruments

- Transferability: Negotiable instruments can be transferred multiple times until they reach maturity. Instruments "payable to the bearer" are negotiated by delivery, while those "payable to order" require delivery and endorsement. The transferee gains the right to transfer the instrument again.

- Independent Title: Unlike other parties, a transferee of a negotiable instrument can possess an independent title even if the transferor has a defective title. This is because the defect in the transferor's title does not affect the transferee's rights when they receive the instrument for value in good faith.

- Presumptions: Negotiable instruments are governed by certain presumptions outlined in Sections 118 and 119 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881.

- Incidental Rights: When a negotiable instrument is dishonored, the transferee has the right to sue in their own name without notifying the original debtor of the transfer. This means that the transferee can bring a claim against the negotiable instrument without informing the original debtor that they have taken possession of it.

- Certainty:. negotiable instrument should be framed clearly and concisely, indicating the contract in as few words as possible. It should specify a fixed amount of money to be paid and be free from irregularities that could hinder its transferability and negotiation.

- Prompt Payment:. negotiable instrument facilitates prompt payment to the holder, as failure to do so could result in a loss of credit for the parties involved.

Categorization of Negotiable Instruments

Negotiable instruments can be classified into various categories, some of which are outlined in the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881. Let's explore these classifications in detail:

Inland Instruments

- Inland instruments are defined in Section 11 of the NI Act, 1881.

- These instruments are either payable in India or drawn upon a person who is a resident of India.

- Examples include promissory notes, bills of exchange, and cheques.

Foreign Instruments

- Foreign instruments are those that do not qualify as inland instruments.

- They are either payable or drawn upon a person who is not a resident of India, or they are drawn and made payable outside India.

- Foreign instruments are mentioned in Section 12 of the NI Act, 1881.

Bearer Instruments

- Bearer instruments include promissory notes, bills of exchange, or cheques that are expressly payable or endorsed in blank.

- These instruments are payable to the bearer, meaning the person holding the instrument can claim payment.

Order Instruments

- Order instruments are payable on order, either to a specific person or without any restriction on transferability.

- This type of instrument allows the holder to transfer it to another person by endorsing it.

Demand Instruments

- Demand instruments are those without a specified time for payment.

- They can be made payable on presentation or on sight.

- This type of instrument is covered under Section 19 of the NI Act, 1881.

Inchoate Instruments

- As per Section 20 of the NI Act, 1881, an inchoate instrument is one that is signed and delivered on stamped paper by one party, either wholly blank or as an incomplete negotiable instrument.

- It can also refer to an unregistered instrument that becomes effective only when a prima facie error is rectified.

- In simpler terms, an inchoate instrument is any cheque, promissory note, or bill of exchange signed by the maker despite being unfilled or unrecorded.

- Judicial pronouncements, such as Magnum Aviation (Pvt.) Ltd. vs. State and Ors (2010), recognize a cheque as an inchoate instrument if it lacks one or more essential characteristics of a negotiable instrument.

Ambiguous Instruments

- Ambiguous instruments are those that are unclear on their face regarding how they should be treated.

- Under Section 17 of the NI Act, 1881, the holder of the instrument has the power to decide whether to treat it as a bill or a note.

Key Types of Negotiable Instruments Under the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881

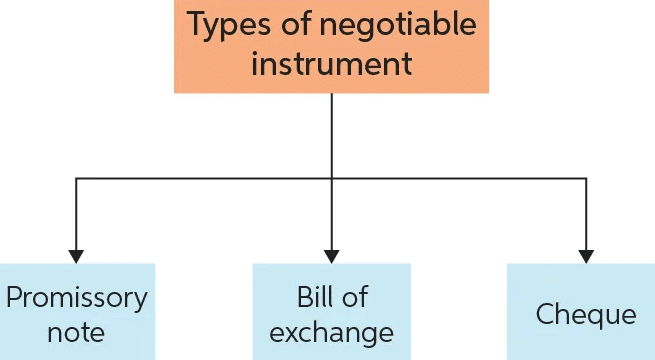

Negotiable instruments are classified into three main types under Section 13 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881:

- Promissory Notes. Defined in Section 4 of the Act.

- Bills of Exchange. Covered under Section 5 of the Act.

- Cheques. Detailed in Section 6 of the Act.

1. Promissory Note (Section 4 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881)

- A promissory note, as per Section 4 of the NI Act, 1881, is a written instrument (excluding banknotes or currency notes) that features an unconditional promise, signed by the maker, to pay a specific amount of money either to a specific person, their order, or the bearer of the instrument.

Specimen of promissory note

I _________ (debtor), S/o _______, Promise to Pay ________ (creditor), S/o _________, or Order, on demand the sum of Rs. 1,00,000 (Rupees One Lakh Only) with interest at rate of 5% p.a. From the date of the value received in cash/cheque no._____ dated _______.

Place:

Date:

Sign:

_______

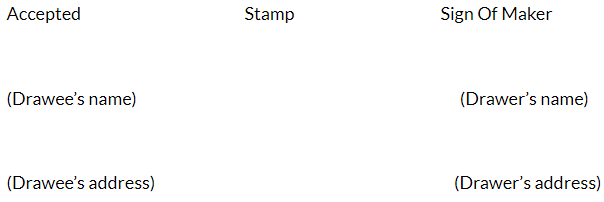

2. Bill of Exchange (Section 5 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881)

Definition. A bill of exchange, as defined in Section 5 of the Act, is a written negotiable instrument that contains an unconditional order, signed by the maker, directing a specific person to pay a certain amount of money to a designated person or to the bearer of the instrument.

Specimen of a bill of exchange

Bill of Exchange

Rs. 60,000/-

90 days after the date, pay Mr. X, or order a sum of Rupees Sixty Thousand Only for the value received.

Parties Involved in a Bill of Exchange

- The Drawer: This individual creates the bill and holds secondary liability.

- The Drawee: This party has primary liability and is the one on whom the bill is drawn.

- The Payee: This is the person who is designated to receive the payment specified in the bill of exchange.

Characteristics of a Bill of Exchange

- A bill of exchange must be written, properly stamped, and accepted by the drawee or their authorized representative.

- It should clearly represent an unconditional command to pay a specified sum of money.

- The amount payable must be definite; a bill of exchange cannot stipulate payment of an indeterminate sum of money.

Types of Bills of Exchange

- Foreign Bills and Inland Bills: Inland bills are those drawn and paid within the same country, while foreign bills involve a bill issued in one country and executed in another. For instance, a bill of exchange drawn and paid in India is an inland bill, but if drawn in India and executed outside its territory, it becomes a foreign bill.

- Trade Bills: These bills are created to settle a credit transaction between parties, where one party accepts the bill in lieu of payment.

- Demand Bills:. demand bill is a type of bill of exchange that is payable on demand, without any specified time limit for payment.

- Time Bills: Unlike demand bills, time bills are payable on a specific date and time, which is usually mentioned on the bill.

- Accommodation Bills: These bills are not drawn for payment in trade transactions but serve as an agreement for providing financial assistance between the parties involved.

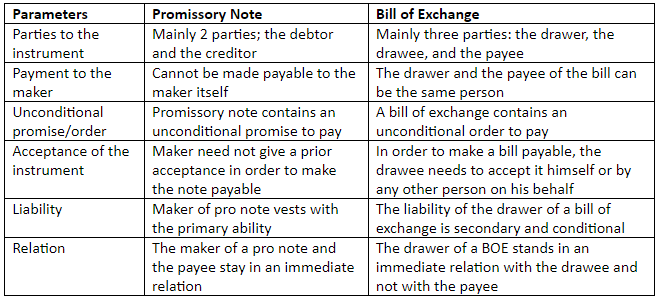

Difference between a Promissory Note and a Bill of Exchange

- Nature of Commitment:. promissory note involves an unconditional promise to pay, whereas a bill of exchange entails an unconditional order to pay.

- Number of Parties:. promissory note involves two parties, while a bill of exchange includes three parties.

- Acceptance Requirement: Acceptance of a promissory note is not necessary, but a bill of exchange must be accepted by the drawee.

- Liability: The drawer of a bill of exchange has secondary liability, while the liability of a drawer in a promissory note is absolute.

Cheque

A cheque, as per Section 6 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, is a bill of exchange drawn on a specified banker, payable on demand. This definition includes electronic forms of cheques, such as truncated cheques and cheques in electronic format.

Classification of Cheques

Truncated Cheque:. truncated cheque is one that is shortened in the clearance process. Instead of using a physical cheque, a scanned copy or electronic image is used for payment transmission.

Cheque in Electronic Form: This type of cheque is digitally signed by the maker and is drawn using a secure digital cryptosystem.

Parties to a Cheque

- The Drawer: The individual who creates and signs the cheque.

- The Drawee: The bank on which the cheque is drawn.

- The Payee: The person entitled to receive the amount specified in the cheque.

Characteristics of a Cheque

- A cheque must be in writing and bear the signature of the drawer.

- As a type of bill of exchange, a cheque is payable only upon demand.

- The date of honour must be indicated on the cheque; absence of this date renders the cheque invalid.

- The amount must be stated in both words and numbers. If there is a discrepancy, the amount in words prevails.

Prohibition on Drawing Bearer Bills

- Section 31 of the RBI Act, 1934: Only the Reserve Bank of India or the Central Government can draw, accept, make, or issue bearer Bills of Exchange or Promissory Notes on demand, despite the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881.

- Section 31(2) of the RBI Act, 1934: This section reinforces the prohibition on drawing bearer Bills of Exchange or Promissory Notes on demand.

Supreme Court Rulings on Cheques and Post-Dated Cheques

In the case of Surendra Madhavrao Nighojakar vs. Ashok Yeshwant Badave (2001), the Supreme Court of India made important decisions regarding cheques and post-dated cheques. Here are the key points:

- Definition of a Cheque:. cheque is considered a bill of exchange that the account owner writes, instructing their bank to pay a specific amount on demand.

- Post-Dated Cheques: According to Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act of 1881, a post-dated cheque becomes valid on the date written on it. The six-month period for legal purposes is calculated from this date.

- Payable on Demand: Changing the payment date of a cheque does not alter its nature as being payable on demand.

- Legal Action Against Bankers: Banks can face legal action if they honor a cheque before the date specified on the cheque.

- Meaning of "Payable on Demand": When a cheque is described as "payable on demand," it means the payee can receive payment immediately.

Difference between Cheque and Bill of Exchange

- Drawee:. cheque is always drawn upon a banker, while a bill of exchange can be drawn upon anyone.

- Payment Terms:. cheque is made payable immediately as per Section 19 of the Act, whereas a bill of exchange can be payable at a certain time or immediately.

- Crossing:. cheque can be crossed to make it non-negotiable, but a bill of exchange cannot be crossed.

- Acceptance:. bill of exchange requires acceptance by the drawee, but a cheque does not need to be accepted.

- Stamping:. bill of exchange is always stamped, while a cheque need not be stamped.

- Grace Period:. 3-day grace period is allowed for a bill when it is due for presentation, but no grace period is applicable for the presentation of a cheque.

Cheque vs. Post-Dated Cheque

- Supreme Court Explanation: In the case of Anil Kumar Sawhney vs. Gulshan Rai (1993), the Supreme Court clarified the difference between a cheque and a post-dated cheque based on Sections 5 and 6 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881.

- Post-Dated Cheque as a Bill of Exchange:. post-dated cheque is considered a bill of exchange when it is written or drawn. It only becomes a cheque when it is due on demand.

- Cashing a Post-Dated Cheque:. post-dated cheque cannot be cashed before the date printed on it. Until that date, it remains a bill of exchange under Section 5 of the Negotiable Instruments Act.

- Applicability of Section 138: The requirements of Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act apply only when the post-dated cheque becomes a cheque, which is triggered by the date on the cheque.

- Validity of Post-Dated Cheque:. post-dated cheque is valid as a bill of exchange until the date printed on it. Once that date arrives, it qualifies as a cheque under the Negotiable Instruments Act. If dishonoured, Section 138’s provisions come into effect.

Other Types of Cheques

- Open Cheque: An open cheque allows the holder to withdraw cash directly from the bank's counter.

- Bearer Cheque:. bearer cheque is one where the specified amount is paid to the person named on the cheque.

- Crossed Cheque:. crossed cheque is created by drawing two parallel transverse lines on the top left corner of the cheque. It may also include the terms "not-negotiable" or "A/c payee," making it payable only to the payee's bank account.

- Order Cheque: An order cheque is issued to a specific person by crossing out the word "bearer" on the cheque.

Holder and Holder in Due Course

Holder of an Instrument

- According to Section 8 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, the payee is the initial holder of the instrument because they have the right to possess it. However, the payee can transfer the instrument to another person to settle a debt, a process known as negotiation. Therefore, the holder of an instrument can be either the bearer or the endorsee.

Holder in Due Course

- As defined in Section 9 of the Act, a holder in due course is someone who, for consideration and in good faith, possesses a negotiable instrument even before the amount specified on it becomes payable. It is crucial that the holder in due course obtains the instrument before its maturity and without any notice of defects in it. A person who acquires a negotiable instrument in good faith and for value is considered a “holder in due course.” In fact, all holders of negotiable instruments are deemed to be holders in due course. In case of a dispute, it is the responsibility of the party liable for repayment to prove that the holder is not the rightful owner.

- However, the burden of proof lies with the holder to demonstrate that they are a holder in due course, by showing that they acquired the negotiable instrument in good faith and for value, if the parties liable for repayment can prove that the instrument was obtained from its rightful owner through illegal means or coercion. The “burden of proof” refers to the obligation to establish certain facts.

Difference between Holder and Holder in Due Course

- A “holder” is someone who has the legal right to possess a promissory note, bill of exchange, or cheque in their own name and can receive or collect payment from the parties involved.

- A “holder in due course” is a holder who accepts the instrument in good faith, with due care and prudence, for value (consideration), and before its maturity.

- Holders are not required to make payment and can also acquire the instrument after it has matured.

- Holders do not possess any specific rights, whereas holders in due course have certain rights. For example, a holder in due course cannot argue that the amount they filled in on an instrument exceeded the authority granted.

- The endorsement may be considered irregular, and the endorsee (such as AB and Co.) may not be a holder in due course, although they could be a holder for value. This situation arises when a bill is prepared by X in favor of Z, and Z further endorses the bill in favor of AB and Co.

- The key point is that the holder must have legal custody of the instrument in their own name and be entitled to obtain or recover the sum. Holders can be endorsers, payees, or bearers. Having entitlement means that even if the holder does not use it, they are still entitled to it, and it cannot be taken away from them. According to Section 8 of the Negotiable Instruments Act of 1881, the holder of an instrument has the right to it even if they do not possess it.

- A holder does not receive a title superior to that of their transferor, while a holder in due course receives a title superior to that of their transferor. The status of a holder is less favorable than that of a holder in due course.

- The title of a holder in due course is free from all equities, meaning they cannot raise defenses that prior parties could raise. For instance, if a negotiable instrument is lost and then found by someone through criminal activity (theft), the person who received the instrument through criminal activity is not entitled to any rights regarding any money owed in relation to that instrument. However, if such a document is properly transferred to a person as a holder, they will obtain a good title.

Indorsement in Negotiable Instruments

Indorsement refers to the act of signing a negotiable instrument to transfer its ownership or rights to another party.

Section 15 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 defines indorsement as the act of signing an instrument by the maker or holder for the purpose of negotiation, either on the back, front, or on a slip attached to it.

Essential Ingredients of Indorsement

- Location of Indorsement: Indorsement can be made on the back or front of the instrument or on a separate document attached to it.

- Signature of Endorser: The endorser must sign the instrument, and initials are also acceptable.

- Who Can Endorse: Only the maker or holder of the instrument can endorse it.

- Delivery: Delivery of the instrument is a necessary part of the endorsement process and can be done by the endorser or their agent.

Types of Indorsement

- General Indorsement (Blank): This occurs when the endorser signs their name only, allowing the instrument to be negotiated by mere delivery. For example, if Y endorses a bill payable to him by simply signing his name, it is a blank endorsement.

- Indorsement in Full: This happens when the endorser specifies the name of the person along with their signature. A blank endorsement can be converted into a full endorsement under certain conditions. For instance, if A holds an instrument endorsed by C in blank and writes "Pay to B or order" over C's signature, it becomes a full endorsement.

- Restrictive Indorsement: This type of endorsement restricts the right of the endorsee to further transfer the instrument. For example, if B endorses a bill by saying "Pay B for the account of A," B's right to negotiate further is restricted.

- Sans Recourse Indorsement: This occurs when the endorser excludes their own liability in the endorsement. For instance, if an endorser writes "Pay to B or order sans recourse," they are excluding their liability for payment in case of dishonor.

- Partial Indorsement: While negotiable instruments cannot be endorsed for part of the amount, exceptions exist. For example, if B holds a bill for Rs. 1500 and endorses it as "pay to C or order Rs. 1000," partial endorsement is allowed for the remaining amount.

Legal Effects of Indorsement

- Transfer of Property: Indorsement transfers the property in the instrument from the endorser to the endorsee.

- Right to Negotiate: The right to further negotiate the instrument is vested in the endorsee through indorsement.

- Right to Sue: Indorsement grants the right to sue on the instrument.

- Presumption of Consideration:. negotiable instrument is presumed to be drawn for consideration, as established in legal cases like A.V. Murthy vs. B.S. Nagabasavanna (2002).

Parties to a Negotiable Instrument

Before delving into the types of negotiable instruments, it is crucial to understand who can be a party to such an instrument. According to Chapter III of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, any person capable of contracting under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, is eligible to be a party to a negotiable instrument.

Capacity of Parties to the Negotiable Instrument

- Minor:. minor, as per Section 26 of the Act, is incapable of entering into a contract and therefore cannot bind himself by becoming a party to a negotiable instrument. While a minor may be the drawer, maker, acceptor, or endorser of the instrument, he will not be liable for it. However, the instrument remains binding upon all other parties.

- Agency: According to Section 27 of the Act, a person can bind himself to an instrument by becoming a party to it either personally or through a duly authorized agent. The provision also states that an agent can bind his principal by acting on his behalf, provided he has the necessary authority.

Liability of the Parties

- The liability of parties to a negotiable instrument is outlined in Sections 30 to 32 and Sections 35 to 42 of Chapter III.

Liability of Agent Signing

- Section 28: An agent who signs a promissory note, bill of exchange, or cheque without indicating that he is acting as an agent or without intending to assume personal liability is personally liable for the instrument. This does not apply to those who were misled into believing that only the principal would be responsible.

Liability of Legal Representative Signing

- Section 29:. legal representative of a deceased person who signs a promissory note, bill of exchange, or cheque is personally bound by the instrument unless he explicitly limits his duty to the amount of assets he received in that capacity.

Liability of Drawer

- Section 30: The drawer of a bill of exchange or cheque is liable to pay the holder compensation if the drawee or acceptor dishonours the instrument, provided the drawer has received proper notice of the dishonour.

Liability of Drawee of Cheque

- Section 31: The drawee of a cheque is obligated to make payment when required and, if payment is not made, must reimburse the drawer for any resulting losses or damages. This applies even if the drawee has sufficient funds legally applicable to the payment of the cheque.

Liability of Maker of Note and Acceptor of Bill

- Section 32: The maker of a promissory note and the acceptor of a bill of exchange are required to pay the amount due at maturity according to the terms of the note or acceptance, unless otherwise agreed. The acceptor of a bill of exchange at or after maturity must pay the amount due to the holder upon demand. Any party who is not paid as required is entitled to reimbursement for losses or damages from the maker or acceptor.

Liability of Indorser

- Section 35: The endorser of a negotiable instrument is liable to the holder and any subsequent endorsers if the instrument is dishonoured, unless there is an agreement to the contrary. The endorser's liability is secondary and arises only if the instrument is dishonoured following proper procedures.

- Section 40: The indorser is released from responsibility to the holder to the same extent as if the instrument had been paid in full when the holder destroys or weakens the indorser's remedy against a preceding party without the indorser's consent.

Liability of Prior Parties to the Holder in Due Course

- Section 36: Every prior party to a negotiable instrument is liable to a holder in due course until the instrument is duly satisfied.

Discharge from Liability of Parties

- Chapter VII of the Act addresses the concept of discharge from liability of parties involved in a negotiable instrument, specifically the maker, acceptor, or endorser. When a party is discharged from liability regarding a particular instrument, only that party is released, while the instrument remains negotiable. All other undischarged parties continue to be liable on the instrument.

Modes of Discharge from Liability

Chapter VII not only discusses the concept of discharge from liability but also its various modes. The modes of discharge from liability of parties in brief are:

- By Mutual Agreement: Parties can mutually agree to discharge one party from liability.

- By Novation:. new party can be substituted in place of the discharged party with the consent of all parties involved.

- By Alteration: The terms of the instrument can be altered in such a way that the discharged party is no longer liable.

- By Expiry: The liability can expire after a certain period as agreed by the parties.

- By Payment: The discharged party can be released from liability by payment of the amount due under the instrument.

Modes of Discharge of a Negotiable Instrument

The party liable on a negotiable instrument can be discharged from the instrument by mode of payment, cancellation, or release.

Discharge by Payment

- According to Section 82(c) of the Negotiable Instruments Act, a party can be discharged from liability through payment if the payment is made in due course, as per the terms and conditions and in good faith.

- Section 79 defines "payment" to include the principal amount of the instrument along with any applicable interest. If the interest is not specified, it is deemed to be 18% as per Section 80 of the Act.

Discharge by Cancellation

- Under Section 82(a), a maker, holder, or endorser is discharged from liability when the name of the acceptor is cancelled from the instrument. This releases the maker, holder, or endorser from liability against the person whose name is cancelled.

Discharge by Release

- As per Section 82(b), when the maker, holder, or endorser of an instrument notifies the party of discharge, the holder is released from all liabilities thereafter.

Crossing of Cheques

- Crossing of a Cheque refers to the practice of drawing two parallel transverse lines across the face of a cheque, usually in the upper-left corner. This action serves as a directive to the paying banker, ensuring that the payment is made under specific conditions. Chapter XIV of the relevant legal framework deals with the intricacies of cheque crossing.

Significance of Crossing a Cheque

- Payment Security: Crossing a cheque is a protective measure to ensure that payment is received only by the rightful holder of the cheque.

- Banker’s Authority: When a cheque is crossed, the banker is given the authority to obtain payment, adding a layer of security to the transaction.

- Traceability: Crossing provides a mechanism for tracing transactions, even in cases of wrongful delivery, as the maker can track the payment through the banker.

Who May Cross a Cheque

- Drawer: The person who issues the cheque can cross it either generally or specially.

- Holder: The holder of the cheque, upon receiving an uncrossed cheque, has the authority to cross it and can add restrictions like “not negotiable.”

- Banker:. banker receiving a specially crossed cheque can cross it again for negotiation with another banker.

Modes of Crossing a Cheque

General Crossing:

- Defined in Section 123 of the Negotiable Instruments Act.

- Occurs when there are no words between the crossing lines or the name of a bank is absent.

- The drawer can add “not negotiable” to the cheque if desired.

Special Crossing:

- Outlined in Section 124 of the Act.

- Happens when a banker’s name is written between the crossing lines.

- Ensures payment can only be made through the specified banker.

Not-Negotiable Crossing:

- Governed by Section 130 of the Act.

- Occurs when “not negotiable” is written between the crossing lines.

- Restricts further negotiation of the instrument.

- The maker cannot pass on a title they do not possess.

Penal Provisions of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881

The criminal penalties outlined in Sections 138 to 148 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, are designed to ensure the enforcement of contracts involving cheques as a method of deferred payment. Section 138 specifies the conditions under which a complaint can be filed for cheque dishonour. The key elements required to comply with Section 138 include:

- Issuance of a Cheque:. person must issue a cheque to pay someone else for a debt or obligation.

- Presentation to Bank: The cheque must be presented to the bank within three months of its issuance.

- Dishonour Reasons: The cheque is returned unpaid by the bank due to insufficient funds or because it exceeds an agreed-upon limit with the bank.

- Notice of Dishonour: The payee must issue a written notice to the drawer within 15 days of learning that the cheque was dishonoured, demanding payment.

- Failure to Pay: The drawer must fail to make the payment to the payee within 15 days of receiving the notice.

Introduction to the Negotiable Instruments Act

The Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, regulates the use of negotiable instruments like cheques, bills of exchange, and promissory notes. Chapter XVII, comprising Sections 138 to 142, was introduced to enhance trust in banking operations and legitimize negotiable instruments in commercial transactions. Dishonour of Negotiable Instruments

Occasionally, a negotiable instrument may be dishonoured when the responsible party fails to make the payment. In such cases, the holder has the right to file a lawsuit for recovery after providing the necessary notice of dishonour. However, before initiating legal action, the holder can obtain a certification from a Notary Public regarding the dishonour, known as “protest.” This certification serves as evidence of dishonour in court.

Overview of Section 138

The Negotiable Instruments Act was initially introduced in 1866 and enacted in 1881. Chapter XVII, including Sections 138 to 142, was added in 1988. Section 138 outlines the punishment for dishonouring a cheque, defining a cheque as a negotiable document drawn on a designated banker. The definition of a cheque under Section 6 includes electronic cheques and truncated cheques. Prior to this amendment, cheque dishonour cases were limited to civil and alternative dispute resolution methods. Now, payees have access to both civil and criminal remedies.

In the case of Modi Cement Limited vs. Kuchil Kumar Nandi (1998), the court emphasized that the primary objective of Section 138 is to enhance the efficiency of banking operations and ensure trust in cheque transactions. Negotiable instruments are designed to facilitate trade and commerce by providing sanctity to credit instruments that are convertible into money and transferable.

In the recent ruling of P Mohanraj vs. M/S. Shah Brothers Ispat Pvt. Ltd. (2021), the court observed that proceedings under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instrument Act against corporate debtors are not prohibited by Section 14 of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016. The court characterized Section 138 proceedings as “civil sheep” in “criminal wolf’s clothing.”

Conditions for Offense under Section 138

A negotiable instrument, as defined in Section 13, includes promissory notes, bills of exchange, or cheques payable to order or bearer. It signifies an instrument promising the bearer a sum of money payable on demand or at a future date. Section 138 outlines penalties for dishonouring a cheque as a criminal offense. The provision specifies conditions that make cheque dishonour illegal:

A cheque must be prepared by the drawer for payment to another party to settle a debt.

The cheque should be presented to the bank within three months.

Dishonour reasons include insufficient funds or exceeding an agreed limit with the bank.

The payee must issue a notice of dishonour within 15 days of learning about it.

The drawer must fail to make payment within 15 days of receiving the notice.

Process of Cheque Payment and Dishonour

- The cheque is presented to the drawee bank for payment. If there are insufficient funds or the amount exceeds the agreed limit, the bank will return the cheque unpaid.

- The bank must receive the cheque within six months of its issuance or within its validity period, whichever is shorter.

- If the bank dishonours the cheque, it issues a “Cheque Return Memo” to the payee.

- The payee, upon receiving the memo, must send a demand notice to the cheque drawer within 30 days.

- The drawer is required to make the payment within 15 days of receiving the notice. If not, the payee can file a lawsuit within 30 days after the 15-day period.

Decriminalisation of Section 138

Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 relates to the dishonour of cheques and the legal consequences that follow. In 2020, the Indian government proposed the decriminalisation of certain minor offences, including those under Section 138, to enhance business confidence and streamline the legal process.

- Proposal for Decriminalisation: The government sought feedback on decriminalising various offences, aiming to simplify business procedures and encourage investment.

- Concerns about Deterrence: Critics argue that removing criminal penalties from Section 138 could undermine its deterrent effect, which serves to prevent breaches of agreements made via cheques.

- Impact on Legal System: Decriminalising certain offences might not alleviate the backlog in magistrate courts. Instead, it could shift the burden to civil courts, as cheque holders would bear the responsibility of pursuing claims.

Cognizance of Offence under Section 142

- Section 142 Overview: Section 142 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 deals with the cognizance of offences under Section 138, which pertains to the dishonour of cheques.

- Cognizance Criteria: According to Section 142(1)(a), a court can take cognizance of an offence under Section 138 only on the written complaint of the payee of the cheque or the holder in due course.

- Limitation Period: As per Section 142(1)(b), the complaint regarding the dishonour of a cheque must be filed within one month from the date of the offence under Section 138. However, the court may waive this limitation if the complainant provides a valid reason for the delay.

- Competent Courts: Section 142(1)(c) authorises Metropolitan Magistrates or Judicial Magistrates of the first class to take cognizance of offences under Section 138.

- Jurisdiction for Trial:Section 142(2) specifies that offences under Section 138 can be tried in the following jurisdictions:

- The branch of the bank where the payee maintains their account, or

- The branch of the drawee bank.

- Defences Not Allowed:Section 140 of the Act states that the defence of potential dishonour on presentment cannot be raised by the drawer of the cheque. However, the court may consider defences such as:

- Lack of jurisdiction or wrong jurisdiction,

- Absence of the 15-day notice,

- Non-return of the cheque by the payee,

- Non-compliance with Section 142 in filing the complaint.

- Summary Trials: Offences under Chapter XVII of the Act, including those under Section 138, are to be dealt with summarily as per Sections 262–265 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973. The sentence passed by the magistrate must not exceed one year, and the fine should not exceed 5000 rupees.

- Timely Disposal: Section 143(3) mandates that every trial conducted by the magistrate under this provision should be concluded within six months from the date of filing the complaint.

Recent Trends in Speedy Disposal of Negotiable Instrument Cases

- The Delhi High Court addressed the possibility of resolving a criminally compoundable offence under Section 138 through mediation in the case of Dayawati vs. Yogesh Kumar Gosain (2017). The Court determined that, although the legislature did not explicitly provide for this option, criminal courts are allowed to refer both the complainant and the accused to alternative dispute resolution methods. The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, does permit and acknowledge settlements without prescribing a specific method.

- Therefore, there is no restriction on using alternative dispute resolution mechanisms such as arbitration, mediation, and conciliation to settle disputes falling under Section 320 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. It was further contended that proceedings under Section 138 of the 1881 Act are distinct from typical criminal cases and resemble civil wrongs with criminal implications.

- The Honourable Supreme Court, in Meters and Instruments (P) Ltd. vs. Kanchan Mehta (2017), emphasized that an offence under Section 138 is fundamentally a civil wrong. Section 139 shifts the burden of proof to the accused, requiring it to be established on the "preponderance of probabilities." Typically, cases under this section should be tried summarily, following the provisions for summary trials in the CrPC, with necessary adaptations for Chapter XVII proceedings.

- Section 258 of the CrPC applies, allowing the Court to dismiss the case and release the accused if the cheque amount, along with assessed costs and interest, has been paid, and there is no reason to continue the punitive aspect. Compounding at the initial stage is encouraged but not prohibited later, subject to acceptable compensation agreed upon by the parties or the Court. The primary aim of this provision is compensatory, with the punitive element serving to enforce the compensatory aspect.

- Typically, cases under Chapter XVII should be tried in a summary manner. It is important to note that the court with jurisdiction under Section 357(3) CrPC can grant appropriate compensation in addition to the imprisonment sentence under Section 64 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, and has recovery powers under Section 431 of the CrPC. The Magistrate may, under the second proviso to Section 143 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, decide against summary trial if a sentence exceeding one year is warranted. This approach does not necessarily require a prison term exceeding one year in every case.

- The bank's slip serves as prima facie evidence of the dishonoured cheque, eliminating the need for additional preliminary evidence by the Magistrate. The complainant's evidence can be submitted via affidavit, subject to the court's discretion and scrutiny of the affiant. This type of affidavit testimony is admissible at all stages of a trial or legal proceeding. Thus, the intention is to proceed with the case in a summary manner.

Other Important Provisions under Chapter XVII

Presumption in Favour of the Holder

- Section 139 establishes a presumption that the cheque issued to the holder was in discharge of a liability, either in whole or in part.

Offences by Companies

- Section 141 holds companies accountable for offences under Section 138. In such cases, the person in charge of the company's affairs at the time of the offence, along with the company, will be liable and prosecuted. The defence of due diligence and good faith is not applicable in cases where a company is accused under Section 138. However, proceedings cannot be initiated against a Director of a company employed by the Central Government or a State Government.

Mode of Service of Summons

- Section 144 mandates that a copy of the summons must be served to the accused or witness at their place of residence or work.

Evidence on Affidavit

- Section 145 allows the complainant's evidence to be presented on affidavit, and the court has the authority to summon and examine the person providing the affidavit.

Compoundable Offences

- Section 147 states that all offences under this Act are compoundable as per the provisions of the CrPC.

Recent Changes to the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881

- The Negotiable Instruments (Amendment) Act, 2018, which came into effect on September 1, 2018, introduced two significant provisions to Chapter XVII of the Act: Sections 143A and 148.

Interim Compensation (Section 143A)

Section 143A allows courts to grant interim compensation to the complainant in cases under Section 138. Key points include:

- The interim compensation cannot exceed 20% of the cheque's amount.

- Compensation must be paid within 60 days, with a possible extension of 30 days.

- The compensation is to be received as a fine under Section 421 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC).

Power of Appellate Court (Section 148)

Section 148 empowers the Appellate Court to order payment during the appeal process. Important aspects include:

- The Appellate Court may require the appellant to deposit 20% of the fine or compensation as part of the appeal.

- This amount is in addition to any compensation granted under Section 143A.

- The deposit must be made within 60 days, with a possible extension of 30 days for valid reasons.

Other Essential Provisions of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881

Chapter XVIII of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 addresses the notice of dishonour related to negotiable instruments. The following sections outline the key provisions:

Section 91: Dishonour by Non-Acceptance

- This section pertains to the dishonour of a negotiable instrument when it is not accepted within a reasonable timeframe upon presentment.

- If the instrument is not duly accepted when presented, it is considered dishonoured.

Section 92: Notice of Dishonour by Non-Payment

- Section 92 addresses the situation where an instrument is dishonoured due to non-payment.

- It occurs when the maker of the instrument fails to make the required payment.

Section 93: Parties Involved in Notice of Dishonour

- This section specifies the parties responsible for giving notice of dishonour.

- When a negotiable instrument is dishonoured, the liable party must notify the holder or any other party to whom they are accountable.

Noting and Protest

- Section 99: Noting of Dishonour

- When an instrument is dishonoured due to non-acceptance or non-payment, a notary public may note the dishonour on the instrument or an attached paper.

- Section 100: Protest of Dishonour

- The notary public's certification of the noting constitutes a protest of dishonour.

Chapter X: Reasonable Time Provisions

- Section 105: Reasonable Time for Presentation

- The reasonable time for presenting an instrument or sending notice of dishonour depends on the usual course of transmission, excluding bank and public holidays.

- Section 106: Reasonable Time for Notice of Dishonour

- If the holder and the party receiving notice of dishonour are in different locations, notice is considered timely if dispatched by the next post or the day after dishonour.

Chapter XVI: International Law and Negotiable Instruments

- Section 134: Governing Law for Foreign Negotiable Instruments

- Foreign negotiable instruments are governed by the laws of the country where they are made.

- Section 135: Governing Law for Dishonoured Instruments

- When a foreign instrument is dishonoured, the law of the place where it is payable applies.

Presumption as to Foreign Law (Section 137)

- Unless proven otherwise, the laws of the foreign country where an instrument is made are presumed to be similar to Indian laws governing negotiable instruments.

Presumption as to Service of Notice

- A notice is presumed to be served if sent by registered mail to the correct address of the cheque's drawer.

- The drawer can contest this presumption.

- The Supreme Court has ruled that a notice is properly served if delivered to the correct address and returned with indicators such as "refused," "no one was home," or similar phrases.

Requirement of Stamp

- Although the Act does not explicitly mention the requirement of a stamp, all types of promissory notes and bills of exchange must bear a stamp.

- The Indian Stamp Act of 1899 mandates the affixation of a stamp on such documents.

Presumptions under Section 118 and Section 119 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881

- Section 101 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872: The plaintiff bears the initial burden of proving a prima facie case. Once the plaintiff establishes this, the defendant must present evidence supporting the plaintiff's case. The burden of proof may shift back to the plaintiff as the case progresses.

- Section 118 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881: Presumptions Unless proven otherwise, the following presumptions apply:

- Consideration: It is presumed that a negotiable instrument is drawn for consideration. When a negotiable document is accepted, inscribed, or transferred, it is assumed to be for (or against) consideration. In cases of cheque dishonour, the accused can discharge their responsibility by showing that no amount is due to the complainant under the instrument.

- Date:. negotiable instrument is presumed to be drawn on the date specified on its face.

Presumptions under Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881

- Time of Acceptance: It is presumed that negotiable instruments are accepted within a reasonable time after their execution date and before their maturity.

- Time of Transfer: Every transfer of a negotiable instrument is assumed to occur before the instrument's maturity date.

- Order of Indorsements: The endorsements on a negotiable instrument are assumed to be made in the order they appear.

- Holder in Due Course:. missing promissory note, bill of exchange, or cheque is presumed to be properly marked, implying the concept of holder in due course.

- Stamp: Every possessor of a negotiable instrument is deemed to have obtained it voluntarily and for value. The accused party must prove that the holder is not a holder in good standing.

Dishonour of Negotiable Instruments

- Noting of Dishonour: When a promissory note or bill of exchange is dishonoured by non-acceptance or non-payment, the holder may have the dishonour noted by a notary public.

- Protest of Dishonour: The holder may also have the instrument protested by a notary public within a reasonable time regarding the dishonour.

Legal Precedents

- Chinnaswamy vs. Perumal (1999): Refuted the assumption under Section 118 of the Negotiable Instruments Act.

- Ayyakannu Gounder vs. Virudhambal Ammal (2004): Clarified the application of Section 118.

- Bonala Raju vs. Sreenivasulu (2006): Established the presumption of consideration under Section 118.

Section 119: Presumption of Protest

- Discusses the presumption of protest in cases of nonpayment of promissory notes or bills of exchange.

- The court will presume nonpayment unless the acceptor refutes the claim.

Recommendations for Improving the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881

To enhance the effectiveness of handling cases under the Negotiable Instruments Act, particularly those concerning cheque bounces, the following measures are recommended:

Increase in Judicial Resources: It is advised to double the number of magistrates dedicated exclusively to handling cheque bounce cases. This increase would allow for a more focused and efficient adjudication process.

Establishment of Special Courts: Special courts should be set up specifically for the swift resolution of cheque bounce disputes. This would streamline processes and reduce the backlog of cases.

Funding and Infrastructure: Adequate funding must be allocated by the government to support the hiring of additional magistrates, their support staff, and the necessary infrastructure to manage increased caseloads effectively.

Case Management: To optimize court time:

- A judicial clerk should conduct roll calls, process adjournment requests, and manage the scheduling of cases that require adjournment before 11 AM.

- From 11 AM onwards, court sessions should focus exclusively on recording evidence, aiming to utilize each hour of court time fully.

Limit on Cases Per Judge: It is recommended that a judge should not handle more than fifty cases per day, ideally split into two sessions of twenty-five cases each, to ensure thorough attention to each matter.

Fee Waivers for Victims: Victims of cheque bounce cases should not be required to pay court fees, as these proceedings do not involve new financial claims.

Presumption and Rebuttal under Section 139: The existing presumption under Section 139 that a cheque has been issued to discharge a debt or liability should be maintained. The accused can counter this presumption by providing credible evidence, shifting the burden of proof back to the complainant.

Streamlined Judicial Process: The court should employ a pragmatic approach in these quasi-judicial proceedings, focusing on the essentials rather than getting entangled in procedural technicalities. A standardized four-hearing process should be implemented:

- Issue a non-bailable warrant if the accused fails to appear at the first hearing.

- Allow the accused to justify and present their defense at the second hearing.

- Conduct cross-examinations during the third hearing.

- Hear final arguments and deliver the judgment at the fourth hearing.

Prevent Misuse of Legal Provisions: The judiciary must ensure that provisions like Section 138 are not exploited to delay payments unjustly. Prompt and effective legal actions should be enforced to uphold trust and confidence in credit transactions.

Conclusion

The Indian judicial system is currently facing a significant backlog of cases, with approximately 20% of litigation-related issues involving cheque bounces, as highlighted in the 213th Law Commission Report. The recently enacted provisions aim to revive the dormant sections of the Negotiable Instruments Act of 1881. Although cases of cheque bounces are penal in nature and constitute criminal offences, the procedures for summary judgment remain in place. Making these offences subject to bail has rendered them akin to civil matters. The newly introduced restrictions are a proactive measure to uphold the legitimacy of cheques. When accused individuals or appellants deposit substantial sums, they are likely to take the situation seriously. While progress is being made, further work is needed to enhance the feasibility of cheque bounce cases, ensuring that summary trials are given their true meaning. Otherwise, the significance of treating cheque bounces as criminal offences may diminish.

Beyond its importance in cheque bounce cases, the Negotiable Instruments Act of 1881 is a crucial piece of legislation governing various negotiable instruments in India. It provides a comprehensive legal framework covering all aspects of negotiable instruments, from their creation to enforcement. The Act outlines the rights and liabilities of parties involved and offers an efficient mechanism for resolving disputes related to negotiable instruments.

FAQs on Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 - Commerce

| 1. What are negotiable instruments under the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881? |  |

| 2. What is the significance of the term 'negotiability' in the context of the Negotiable Instruments Act? |  |

| 3. What are the essential features of a promissory note under the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881? |  |

| 4. What are the legal consequences of dishonor of a cheque as per the Negotiable Instruments Act? |  |

| 5. How does the Negotiable Instruments Act protect the rights of holders in due course? |  |