5 Golden Rules for Para Jumbles | Verbal Ability & Reading Comprehension (VARC) - CAT PDF Download

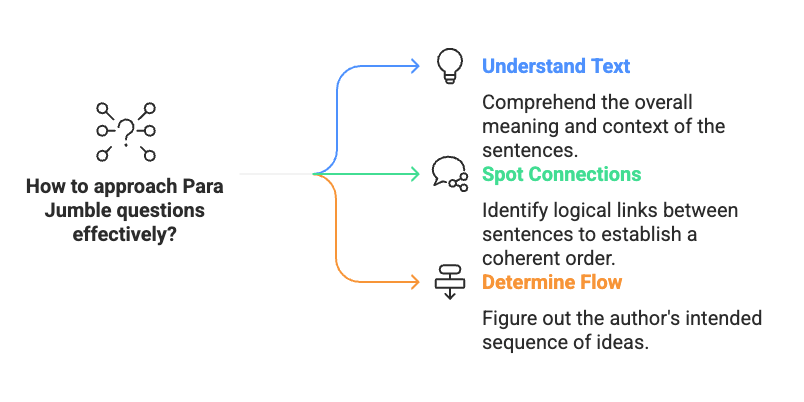

- Mastering Para Jumbles can give you a real edge in competitive exams like CAT. You can expect 2 to 3 Para Jumble questions in the Verbal Ability and Reading Comprehension (VARC) section.

- These tricky sentence rearrangement questions test how well you can spot logical connections, maintain flow, and understand the central idea of a passage.

- Once you understand how these questions are built—and learn a few smart techniques—you’ll be able to tackle them with greater accuracy and confidence.

Understanding the Basics: What is a Para Jumble?

- A Para Jumble question gives you a set of sentences (usually four or five) that, when put in the right order, make a clear and meaningful paragraph.

- Your job is to figure out the correct order.

- Some questions might give you multiple-choice options, but in exams like CAT, you often have to type the answer (TITA format), meaning you need to find the exact order without any choices, so a clear method is very important.

- These questions test how well you understand the text, spot logical connections between ideas, and figure out how stories or arguments are built.

- It’s not just about picking sentences that sound nice together; it’s about figuring out the author’s intended flow of ideas, even though the question setters might have made some changes.

The Question Setter’s Craft: What to Expect

Knowing how Para Jumble questions are created can give you helpful insights. Question setters usually don’t write these paragraphs from scratch. Instead, they pick a paragraph from an existing source, like an article, essay, or book, and then make some changes to it:

- Making It a Standalone Paragraph: If the original paragraph was part of a bigger text, setters edit it to work as a complete, standalone piece. For example, if the first sentence was “Another example is…,” they might change it to “An example is…” to make it a good starting point for the jumbled sentences.

- Ensuring One Clear Order: They choose and edit the sentences so that only one logical and clear order makes sense. This is especially important for TITA questions, where confusion would make the question impossible to solve.

- Removing Some Connecting Words: To make it harder, setters often take out obvious connecting words or phrases (like “however,” “therefore,” “in addition,” “consequently”). This means you’ll need to focus on hidden logical connections, pronoun references, and the flow of ideas instead of relying on clear signal words.

- Combining or Slightly Rewording Sentences: Sometimes, two short sentences from the original text might be joined into one longer sentence for the Para Jumble, or they might slightly reword sentences to fit the question format, but they don’t change the main meaning or connections.

Understanding these changes helps you tackle the jumbled sentences with the right mindset, focusing on the natural logic instead of being confused by missing clues you might expect in unchanged text.

The 5 Golden Rules for Solving Para Jumbles

Here are five important rules to help you solve Para Jumble questions more effectively:

Golden Rule 1: Spot the First Sentence

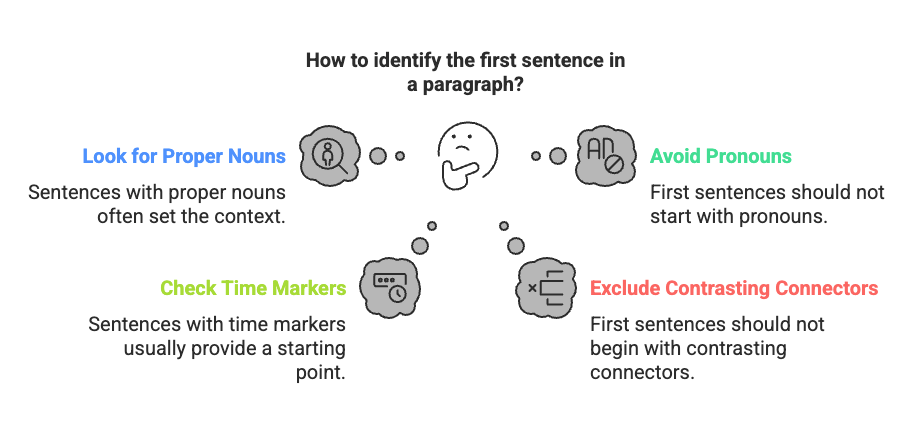

The first sentence in a paragraph usually introduces the main topic, gives a general idea, a definition, or sets the background. It should be a sentence that makes sense on its own and doesn’t begin with a pronoun (like “he,” “this,” or “they”) that refers to something not yet mentioned. Also, it shouldn’t start with linking words like “but” or “also” unless they are part of an opening statement. Sentences that talk about broad topics are usually good starting points, with the following sentences adding more detail or narrowing the focus.

- Added Tip: Look for sentences with proper nouns (e.g., names of people, places, or events) or time markers (e.g., “In 2020”) as they often set the context. For example, a sentence like “In 2020, India faced a major economic challenge” is likely the opener because it provides a clear starting point without needing prior information.

- Common Pitfall: Avoid choosing a sentence that starts with a contrasting connector like “However” or “Nevertheless” as the first sentence, as these imply a prior statement. For instance, “However, the policy failed” cannot be the opener because it suggests something was mentioned before.

- Time Management: In CAT, where Para Jumbles are often TITA (Type-In-The-Answer) questions, spend no more than 30 seconds identifying the first sentence. If unsure, mark a potential opener and move to the next rule, then revisit later.

Golden Rule 2: Look for Repeated Words and Idea Chains

A well-connected paragraph often repeats key words or uses related words and synonyms that link ideas together. These are called “echo words.” When a new idea is introduced, the next sentences usually explain it more, give examples, or show a contrast. Spotting these repeated or related words helps you join sentences correctly. For instance, if a sentence mentions “mind reading,” the next ones may explain it more or compare it with something like “print reading.”

- Practical Example: Consider these sentences: (A) “Mind reading is a new technology.” (B) “It allows users to control devices with thoughts.” (C) “Print reading, on the other hand, relies on physical books.” Sentence A introduces “mind reading,” and B elaborates on it with “It,” making A-B a logical pair. Sentence C contrasts with “print reading,” likely following after A-B are established.

- Added Strategy: If echo words are not obvious, look for synonyms or related concepts. For example, if one sentence mentions “climate change,” another might use “global warming” or “rising temperatures” to continue the idea.

- Tricky Scenario: In XAT, passages might use abstract topics like philosophy. If a sentence mentions “existentialism,” but no other sentence repeats the term, look for related ideas like “human freedom” or “meaning of life” to form connections.

- Time Management: Spend about 45 seconds tracing echo words. If you can’t find clear repetitions, move to the next rule to avoid getting stuck, as CAT’s VARC section (40 minutes for 24 questions) requires efficient pacing.

Golden Rule 3: Follow the Logical Flow of Ideas

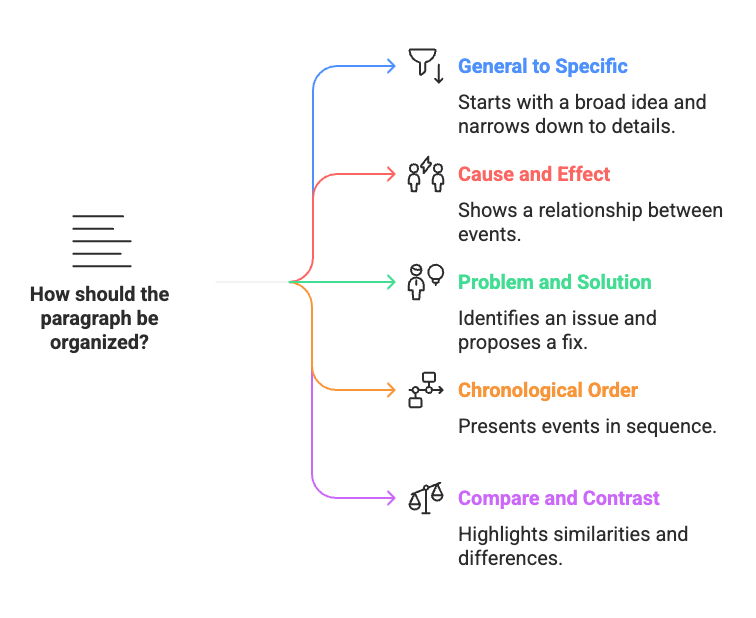

Sentences in a paragraph follow a logical order. Some common ways ideas are arranged include:

General to Specific: Starting with a general idea, then giving examples or details.

Cause and Effect: One sentence talks about a cause, the next shows the result (or the other way around).

Problem and Solution: First, a problem is stated, then a solution is suggested.

Chronological Order: Events or steps are described in the order they happen.

Compare and Contrast: Two ideas or things are shown as similar or different.

Try to understand which pattern the paragraph is following. This helps you arrange the sentences logically.

- Practical Example: For a Cause and Effect pattern: (A) “The city faced severe flooding.” (B) “Heavy rainfall caused the rivers to overflow.” Here, B (cause) logically comes before A (effect). Recognising this pattern helps you order them as B-A.

- Added Tip: In CAT, General to Specific is a common pattern in RC-related Para Jumbles. If a sentence broadly introduces “Artificial Intelligence,” the next might specify “its use in healthcare,” followed by an example like “AI diagnosing diseases.”

- Common Pitfall: Don’t assume chronological order unless time markers (e.g., “first,” “then,” “finally”) are present. A sentence like “The company launched a new product” doesn’t always come before “It failed in the market” unless timing is explicit.

- Tricky Scenario: In SNAP, where passages might be shorter (300–400 words), look for Problem-Solution patterns in business-related topics. A sentence like “The startup struggled with funding” might be followed by “They secured a venture capital deal.”

Golden Rule 4: Understand Pronouns and Linking Words Wisely

Pronouns like “he,” “she,” “it,” “they,” “this,” “that,” and “those” usually refer to something mentioned earlier. For example, a sentence that begins with “These dangers...” must come after a sentence that talks about specific dangers. Also, look for connecting words such as “also,” “too,” “another,” “similarly,” “on the other hand,” and “consequently.” These words show how sentences are related and help you figure out their correct order.

- Practical Example: (A) “The scientist discovered a new species.” (B) “She named it after her mentor.” Here, “She” in B refers to “the scientist” in A, making A-B a mandatory pair.

- Added Tip: In CMAT, where passages might have fewer connectors, look for implicit links. If a sentence says “This method worked well,” the previous sentence must describe a method, even if connectors like “therefore” are missing.

- Common Pitfall: Be cautious with “it” or “this” in abstract topics (common in XAT). For example, “This philosophy…” might refer to a concept like “utilitarianism” mentioned earlier, not a person or object.

- Time Management: Allocate 30–40 seconds to check pronouns and connectors. If pronouns are ambiguous (e.g., “it” could refer to multiple things), use other rules like logical flow to confirm the order.

Golden Rule 5: Find Strong Sentence Pairs and Build Paragraphs in Steps

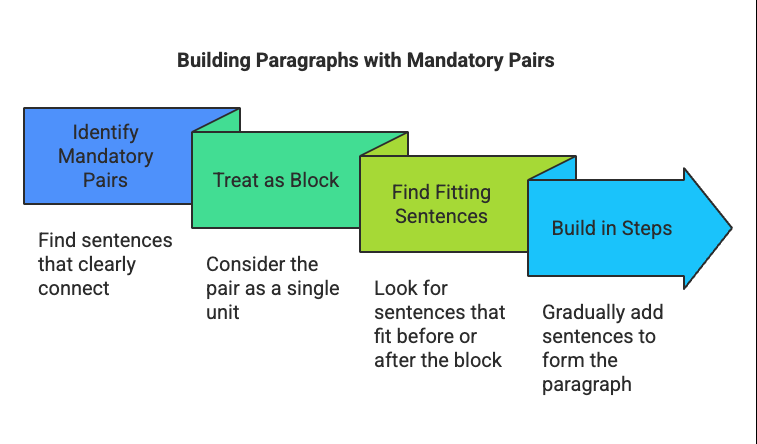

Instead of trying to arrange all the sentences at once, first find pairs of sentences that clearly go together. These are called “mandatory pairs.”

For example, a question in one sentence might be followed by an answer in the next. Or a sentence may introduce a word or idea, followed by a sentence that explains or defines it.

Once you find such a pair, treat it like one block and then look for other sentences that fit before or after this block. Building in steps like this is often easier than solving the whole puzzle at once.

- Practical Example: (A) “What caused the economic crisis?” (B) “The stock market crash was the main reason.” Here, A-B is a mandatory pair because B directly answers A’s question.

- Added Strategy: In NMAT, where time is tight (120 minutes for 108 questions), focus on forming one or two mandatory pairs quickly, then arrange the remaining sentences around them. For instance, if you pair A-B, check if another sentence introduces the topic A discusses.

- Tricky Scenario: If no clear pairs emerge (e.g., in a philosophical XAT passage), look for a sentence with a concluding tone (e.g., “Thus, the theory was proven”) to work backwards, placing it last and arranging others before it.

- Time Management: Spend 1–1.5 minutes forming pairs and building blocks. In CAT, aim to solve a Para Jumble question in 2–3 minutes total, so pace yourself to leave time for verification.

Decoding Para Jumbles from Recent CAT Exams

Example 1

Sentences:

The eventual diagnosis was skin cancer, and after treatment, all seemed well.

The viola player didn’t know what it was, nor did her GP.

Then a routine scan showed it had come back and spread to her lungs.

It started with a lump on Cathy Perkins’ index finger.

Solution:

Golden Rule 1: Sentence 4 introduces the topic (a lump) and a person (Cathy Perkins) with no prior dependency, making it the opener.

Golden Rule 2: Sentence 2’s “it” refers to the lump in 4, forming a 4-2 pair. Sentence 1’s “diagnosis” follows 2’s uncertainty (2-1). Sentence 3’s “it had come back” refers to cancer in 1 (1-3).

Golden Rule 3: The flow is chronological: lump (4), uncertainty (2), diagnosis (1), recurrence (3).

Golden Rule 4: “It” in 2 and “Then” in 3 support the sequence 4-2-1-3.

Golden Rule 5: 4-2 and 1-3 are mandatory pairs, leading to 4-2-1-3.

Order: 4-2-1-3.

Decoded Paragraph: It started with a lump on Cathy Perkins’ index finger. The viola player didn’t know what it was, nor did her GP. The eventual diagnosis was skin cancer, and after treatment, all seemed well. Then a routine scan showed it had come back and spread to her lungs.

Example 2

Sentences:

The more we are able to accept that our achievements are largely out of our control, the easier it becomes to understand that our failures, and those of others, are too.

But the raft of recent books about the limits of merit is an important correction to the arrogance of contemporary entitlement and an opportunity to reassert the importance of luck, or grace, in our thinking.

Such acceptance of our limits has implications for how we organize our own lives, since letting go of individual achievement as the sole yardstick of a life well lived opens us to being more fully alive to the present.

And humility reminds us that the fortunes of those who struggle are as much the result of chance and systemic forces as our own success might be.

Solution:

Golden Rule 1: Sentence 1 introduces the theme of chance in achievements with no prior dependency, making it the opener.

Golden Rule 2: Sentence 4 echoes “chance” and “success” from 1, forming a 1-4 pair. Sentence 3’s “Such acceptance” refers to 1 (1-3). Sentence 2’s “limits of merit” ties to the theme but concludes broadly.

Golden Rule 3: The flow moves from premise (1), elaboration on humility (4), personal implications (3), to a societal conclusion (2).

Golden Rule 4: “Such” in 3 and “And” in 4 link to 1. “But” in 2 places it as a contrasting closer.

Golden Rule 5: 1-4 and 1-3 are pairs. 3-2 fits as a transition to a broader conclusion, leading to 1-4-3-2.

Order: 1-4-3-2.

Decoded Paragraph: The more we are able to accept that our achievements are largely out of our control, the easier it becomes to understand that our failures, and those of others, are too. And humility reminds us that the fortunes of those who struggle are as much the result of chance and systemic forces as our own success might be. Such acceptance of our limits has implications for how we organise our own lives, since letting go of individual achievement as the sole yardstick of a life well lived opens us to being more fully alive to the present. But the raft of recent books about the limits of merit is an important correction to the arrogance of contemporary entitlement and an opportunity to reassert the importance of luck, or grace, in our thinking.

Common Question Patterns in Para Jumbles

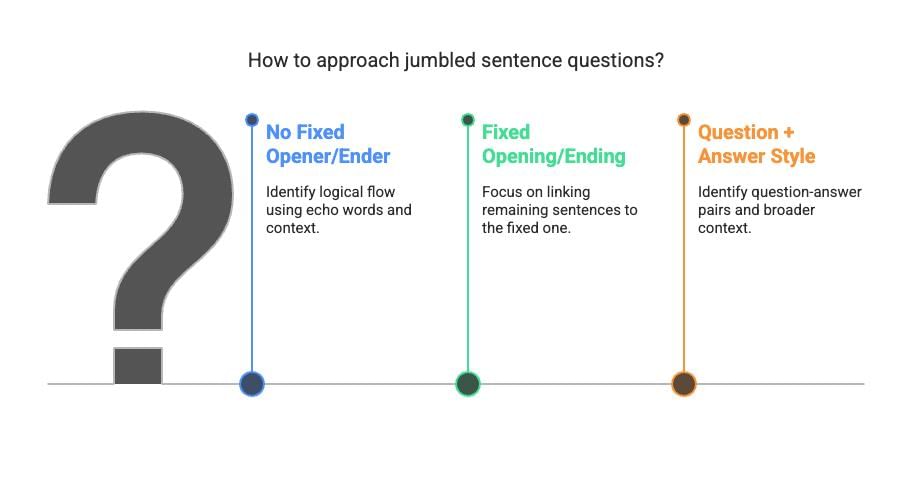

Recognising common Para Jumble patterns helps you anticipate question structures and apply the right strategies. Here are three frequent types:

Type 1: No Fixed Opener/Ender

All sentences are jumbled, with no predetermined first or last sentence. You must identify the logical flow using the 5 Golden Rules.

Example: (A) “Solar energy is renewable.” (B) “It reduces electricity costs.” (C) “Many households are adopting it.” Using echo words (“it” in B and C refers to “solar energy” in A) and logical flow (introduction to adoption), the order is A-B-C.Type 2: Fixed Opening/Ending Sentence

The question specifies the first or last sentence, reducing the number of sentences to arrange. Focus on linking the remaining sentences to the fixed one.

Example: Fixed opener: “Artificial Intelligence is transforming industries.” Jumbled: (A) “It improves efficiency in healthcare.” (B) “Manufacturing also benefits from automation.” A’s “It” links to the opener, and B extends the idea to another sector, making the order Opener-A-B.Type 3: Question + Answer Style

One sentence poses a question or problem, and another provides the answer or solution, forming a mandatory pair.

Example: (A) “Why did the project fail?” (B) “Lack of funding was the primary reason.” (C) “The team faced many challenges.” A-B forms a question-answer pair, and C introduces the broader context, suggesting the order C-A-B.

Extra Tips for Success

- Read All Sentences First: Before arranging, read all sentences to understand the overall topic. This helps you spot the tone (e.g., formal or narrative) and theme (e.g., technology, history), which guides your arrangement.

- Rule Out Bad Starting Sentences: Quickly skip sentences that can’t be first, like those starting with “But…,” “So…,” or a pronoun (e.g., “They failed”) with no clear explanation of who “they” are in the set.

- Look for a Closing Sentence: A sentence that sums up the ideas, gives a final thought, or suggests the future might be the last one. For example, “This innovation will shape the future” often concludes a paragraph about a new technology.

- Practice Often: Regular practice is key to getting better at Para Jumbles. Use past CAT papers or mock tests for this purpose. Aim to solve 5 Para Jumbles daily to build speed and accuracy.

- Don’t Focus on Just One Rule: Combine all the rules, as some will work better depending on the question. For instance, in a chronological Para Jumble, Rule 3 (logical flow) might be more helpful than Rule 2 (echo words).

- Check Your Order: After arranging, read the sentences in your chosen order to ensure the paragraph flows well and makes sense. If a sentence feels out of place (e.g., a detail comes before the topic is introduced), adjust your sequence.

- Added Exam Strategy: In CAT’s TITA format, you’ll type the order (e.g., 1-3-2-4). Double-check by reading the paragraph in your final order to confirm coherence. In multiple-choice formats (like SNAP or CMAT), use the elimination method to rule out sequences that break logical flow or pronoun references.

By following these rules and tips regularly, you can turn Para Jumbles from a confusing challenge into a scoring opportunity in your exam.

|

111 videos|452 docs|90 tests

|

FAQs on 5 Golden Rules for Para Jumbles - Verbal Ability & Reading Comprehension (VARC) - CAT

| 1. What is a para jumble and how does it relate to the CAT exam? |  |

| 2. What are the key strategies for solving para jumbles effectively? |  |

| 3. How much time should I allocate to para jumbles during the CAT exam? |  |

| 4. Are there any common traps to avoid when solving para jumbles? |  |

| 5. Can practicing para jumbles improve my overall performance in verbal ability sections of competitive exams? |  |