Sure Shot Questions for Board Exams: Bricks, Beads and Bones | History Class 12 - Humanities/Arts PDF Download

Introduction

The chapter focuses on the Harappan Civilisation, its urban planning, economic activities, social structure, and decline. Below is a concise Q&A set to help you prepare for class tests, school exams, or board-level assessments with key, repetitive questions.

Key Questions

Q1. What were the key features of Harappan urban planning?

View Answer

View Answer

Key features of Harappan urban planning include:

- Planned layouts: Cities like Mohenjo-daro and Harappa had a grid system for streets.

- Advanced drainage: A sophisticated drainage system was integrated into the city design.

- Standardised bricks: Buildings were constructed using uniform burnt bricks.

- Citadel: A raised area for administration, separate from residential zones.

- Residential areas: Lower towns were designated for housing, showcasing organised living spaces.

Q2. What factors contributed to the decline of the Harappan Civilisation?

View Answer

View Answer

The decline of the Harappan Civilisation around 1900 BCE can be linked to several factors:

- Environmental changes: Shifts in river patterns and climate change may have affected agriculture.

- Invasions: There is speculation about possible invasions or conflicts that disrupted society.

- Internal issues: Social or economic problems could have contributed to the decline.

While these factors are discussed, the precise cause of the decline remains a topic of debate among historians.

View Answer

View Answer

The Harappan civilisation utilised a variety of raw materials for craft production, including:

- Stones: Carnelian, jasper, crystal, quartz, and steatite.

- Metals: Copper, bronze, and gold.

- Shell

- Faience: Fired glazed clay.

- Terracotta: Baked clay.

These materials were obtained through several methods:

- Local Settlements: Sites like Nageshwar and Balakot were near shell sources, while Shortughai in Afghanistan provided lapis lazuli. Lothal was close to carnelian and steatite.

- Trade Expeditions: Expeditions to Rajasthan's Khetri hills for copper and to South India for gold.

- Long-Distance Trade: Copper was sourced from Oman, and gold possibly came via sea routes to Mesopotamia (Meluhha).

Thus, the Harappans either settled near resource-rich areas or established trade networks to acquire necessary materials.

View Answer

View Answer

The primary reason our understanding of the Harappan (Indus Valley) civilisation is less comprehensive than that of other ancient cultures is the undeciphered script. Unlike the texts of Egypt or Mesopotamia, which scholars can read, the Indus script lacks a Rosetta Stone for translation. Key points include:

- We have no direct written records detailing Harappan religion, governance, or laws.

- Our knowledge is based almost entirely on archaeological findings, such as buildings, seals, and beads.

- This reliance on material evidence limits our insights into their political structure, literature, and beliefs.

View Answer

View Answer

Cunningham, the first Director-General of the ASI, faced confusion while studying Harappan sites due to several factors:

- He primarily relied on the itineraries of Chinese pilgrims, which did not include Harappa.

- His focus was on the Early Historic period, leading him to overlook the significance of Harappan artefacts.

- When he received a Harappan seal, he struggled to place it within his familiar time-frame.

- Cunningham believed Indian history began with the first cities in the Ganga valley, causing him to miss the importance of Harappa.

As a result, he did not recognise the age and relevance of the artefacts he encountered

View Answer

View Answer

Marshall's excavation technique involved digging in uniform horizontal layers across the entire mound. This approach had several drawbacks:

- It ignored the site's stratigraphy, mixing artefacts from different periods.

- This led to a loss of valuable context regarding the artefacts.

In contrast, R.E.M. Wheeler focused on excavating along the natural historical layers of the mound:

- His method preserved the chronological context of finds.

- This allowed archaeologists to understand how settlements evolved.

View Answer

View Answer

Harappan seals and sealings played a crucial role in trade by ensuring the security and authenticity of goods. Here’s how they were used:

- Goods were packed in bags, which were tied shut with a rope.

- Seals were pressed into wet clay at the knot, creating an impression.

- If the seal impression was intact upon arrival, it indicated that the shipment was untampered.

- The seal often displayed the sender's name or title, identifying the origin of the goods.

In short, seals ensured security and authenticated goods during long-distance trade.

View Answer

View Answer

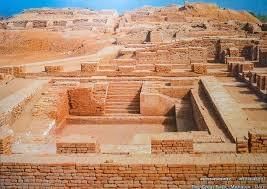

Harappan cities were divided into two main sections:

- Citadel: This was a fortified area built on a high brick platform. It included important public buildings like granaries and baths, indicating its role as a centre for administration and elite activities.

- Lower Town: This section was larger and lower in elevation, featuring houses built on mud-brick platforms. The presence of walls suggests it was also planned for residential purposes.

This division reflects the careful urban planning of Harappan cities.

View Answer

View Answer

Harappan writing has distinct features that set it apart from other ancient scripts:

- Non-alphabetic: The Harappan script consists of around 375 to 400 unique signs, indicating it is not based on an alphabet.

- Direction: It is typically written from right to left, as evidenced by the layout of inscriptions on seals.

- Short inscriptions: Most inscriptions are brief, with the longest containing only about 26 signs, and they remain undeciphered.

View Answer

View Answer

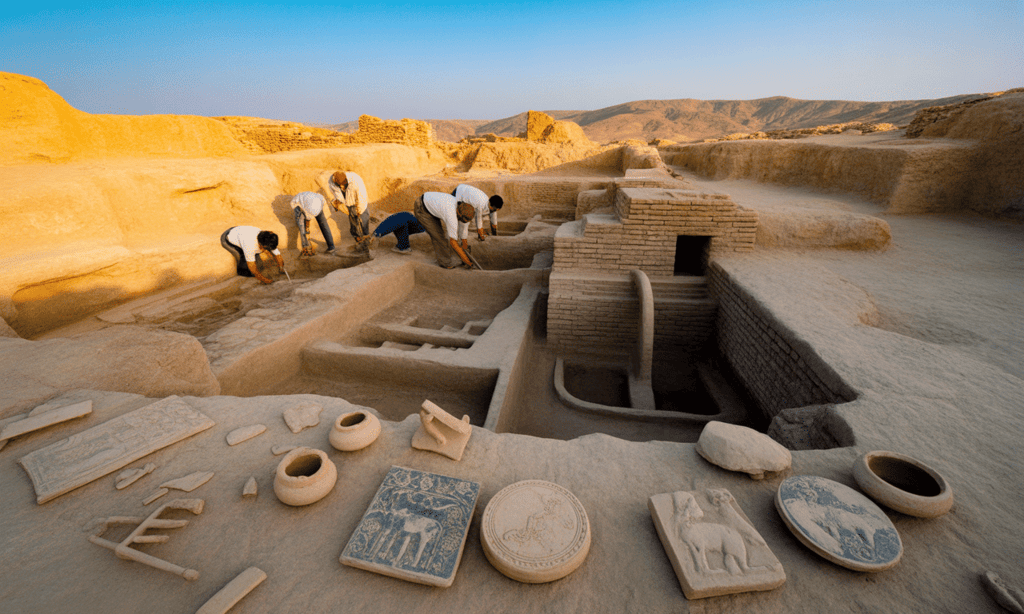

Archaeologists reconstruct the past of the Harappan civilisation through various methods:

- They excavate Harappan sites to uncover material remains such as pottery, tools, seals, weights, and architecture.

- Biological remains, including plant seeds, animal bones, and human skeletons, are also analysed.

- Stratigraphy is used to date different layers of soil and associate objects found within them.

- Collaboration with specialists, like botanists and zoologists, helps identify crops and domesticated animals.

- Evidence of water management, such as sewage systems, irrigation channels, and wells, reveals insights into their infrastructure.

- Unfinished objects and waste from workshops indicate locations of craft production.

- Indirect evidence, such as references in Mesopotamian texts to "Meluhha," aids in understanding trade connections.

By piecing together artefacts, ecofacts, and their contexts, archaeologists create a comprehensive picture of Harappan society, economy, and beliefs.

View Answer

View Answer

The Harappan drainage system was a remarkable feat of urban planning, featuring:

- Brick-lined, covered drains running beneath the streets.

- Each house included a private bathroom, with its outlet connected to the street drains.

- Smaller drains from houses fed into larger channels.

- Rainwater drains, measuring 2–5 feet wide, managed excess water.

- Manholes, made of removable brick slabs, allowed for easy cleaning.

- The streets were laid out in a grid pattern, enhancing organisation.

This advanced system, found in major Harappan towns, is regarded as one of the world's earliest urban sanitation systems

View Answer

View Answer

The Harappans employed various subsistence strategies, including:

- Mixed farming: They cultivated crops such as wheat, barley, rice, millets, pulses (like lentils and chickpeas), and sesame.

- Animal husbandry: Domesticated animals included cattle, sheep, goats, buffaloes, and pigs. They used oxen for ploughing, as indicated by terracotta plough models.

- Fishing and hunting: They consumed wild game, including boar and deer, and fished for additional protein.

- Irrigation: Many Harappan sites were in semi-arid regions, making irrigation essential. Evidence of canals and reservoirs, such as those at Shortughai and Dholavira, suggests they used these systems to water their crops.

View Answer

View Answer

The Harappans used bricks with a uniform ratio of length, breadth, and height (4:2:1) across major sites. This standardisation suggests:

- Centralised planning or shared architectural norms.

- Compatibility in construction, such as drains fitting into houses.

- Administrative control over building projects.

View Answer

View Answer

The Great Bath was a large, watertight tank measuring 30 by 15 feet and about 8 feet deep. It featured:

- Steps at both the north and south ends.

- Corridors surrounding the tank.

Its intricate design and central position in the Citadel imply it had a ceremonial purpose. Most scholars believe it was used for:

- Ritual bathing or purification rites.

- Community gatherings focused on water and cleanliness.

The careful construction of the Bath indicates its significance in religious or social practices.

View Answer

View Answer

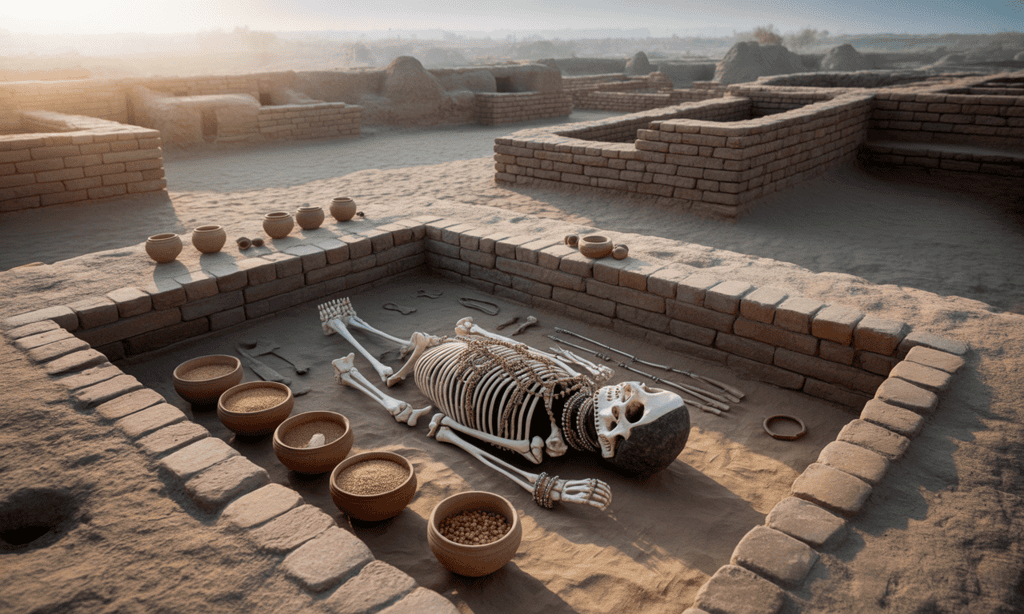

Harappan burials reveal social differences through various features:

a) Burials were typically in north-south pits, sometimes lined with bricks.

b) Grave goods varied significantly:

- Some graves contained pottery, beads, and ornaments.

- Women’s graves often included bangles.

c) Richer burials had more valuable items, indicating social differentiation.

d) However, truly precious items were rarely buried, suggesting limited inequality.

View Answer

View Answer

Luxury items were crafted from rare or imported materials and required skilled craftsmanship. Examples include:

- Glazed faience vessels

- Gold and carnelian jewellery

- Lapis lazuli ornaments

- Intricately carved seals

These luxury artefacts are typically found in major urban sites like Mohenjodaro and Harappa, often in areas associated with the elite. In contrast, smaller villages rarely yield such items. The presence of precious materials, such as gold and imported stones, along with fine craftsmanship in large cities, indicates an urban elite that controlled trade and specialised production.

View Answer

View Answer

Planned Layout: Cities were built on grids with streets at right angles. There was a clear division into citadel and lower town, each walled.

Standardized Architecture: Uniform baked bricks (length=4×height, width=2×height) were used across sites. Public buildings (granaries, baths, warehouses) and large platforms show organized civic design.

Sophisticated Infrastructure: Covered drainage systems with house-connected drains, public wells, and large reservoirs (e.g. Dholavira) indicate deliberate urban planning.

Public Buildings: Structures like the Great Bath, granaries, and the “stupa”-like platforms in the citadel served communal functions. Their scale implies coordinated labor and governance.

Specialized Zones: Entire city quarters (e.g. Chanhudaro) were devoted to crafts (bead-making, metallurgy), while residential sectors had courtyards and no direct street views for privacy.

Economic Complexity: Standard weights and seals indicate regulated commerce; long-distance trade networks connected ports (Lothal) to Mesopotamia. Cities had storehouses and workshops suggesting administration of production and storage.

Population Size: Some settlements covered hundreds of hectares (Harappa, Mohenjodaro), implying tens of thousands of inhabitants.

These features – grid planning, municipal services, uniform construction, and craft specialization – make Harappan civilization distinctly urban and advanced for its time.

View Answer

View Answer

Agriculture: Based on wheat, barley, rice, millets, pulses etc.. They used plows and had wells and possibly canals for irrigation (e.g. Dholavira’s reservoirs). Domestic animals (cattle, sheep, goats, buffalo, pig) provided dairy, meat and labor.

Crafts: Specialized industries (bead-making, metallurgy, pottery, shell-carving) thrived. Workshops at sites like Chanhudaro and Lothal produced beads (carnelian, etc.), shell bangles, and metal tools. Craftsmen sourced raw materials (lapis from Afghanistan, copper from Rajasthan/Oman) through trade or expeditions.

Trade: Harappans traded internally (between cities) and internationally. They exported cotton textiles, beads, pottery; and imported metals, precious stones (lapis, gold). Seals and weights facilitated commerce. Contacts with Mesopotamia (via Persian Gulf) are attested by Harappan seals in Sumerian cities and Mesopotamian texts mentioning “Meluhha”.

Markets and Administration: While no coins are found, standardized weights suggest regulated markets. Large storehouses imply grain storage and redistribution. Some scholars suggest a form of centralized control (maybe by priest-kings or councils) to manage granaries, public works and trade.

View Answer

View Answer

No Central Ruler (Egalitarian): Some argue there was no king or chief; the society may have been relatively egalitarian. Evidence: uniform house sizes in some cities, no obvious palaces or royal tombs, and no grand inscriptions proclaiming rulers. These scholars say local communities collectively managed affairs.

Multiple Local Rulers: Others propose a segmented political structure. For example, Mohenjodaro’s citadel and Harappa’s citadel might each have had its own leader or council, rather than one emperor. Different city-states (or regions like Punjab vs Sindh) could have been semi-autonomous.

Centralized State: A third view sees a unified state. The uniformity in urban planning, weights, seals and brick standards across hundreds of miles suggests coordinated authority. Proponents argue a central power (possibly based in Mohenjodaro or Harappa) oversaw the civilization.

Collective Leadership: Some suggest priest-kings or merchant guilds collectively guided the cities. The absence of royal palaces leaves this open.

View Answer

View Answer

After ~1900 BCE, many Indus cities were abandoned or shrank. Likely causes include:

Environmental Change: Shifting monsoon patterns and climate change led to aridity. The Ghaggar-Hakra (suspected Saraswati) River system dried up, undermining the water supply for agriculture. Floods or tectonic activity may have altered river courses, leaving cities without reliable water (e.g. Mohenjodaro and Harappa may have faced flooding or earthquakes).

Resource Depletion: Intensive farming and deforestation could have reduced soil fertility over centuries, making agriculture less productive.

Trade Disruption: As Mesopotamian and Central Asian trade networks changed (Mesopotamia itself was in decline), Harappan trade may have suffered, removing crucial economic exchanges (like copper, tin, lapis).

Social Transformation: Internal social stress or political fragmentation might have arisen from these pressures, leading to breakdown of urban institutions. Late Harappan settlements often become more rural and dispersed.

The decline was likely gradual and multi-causal: ecological stress (climate and river changes) undermined agriculture and water management, causing food shortages and city abandonment. This cascaded into economic and social collapse. By ~1700 BCE, most major Harappan cities were deserted or significantly reduced, marking the end of the Mature Harappan phase.

Tips for Students

- Revise important terms and definitions: faience, steatite, citadel, lapis lazuli, etc.

- Link material culture with societal functions: e.g., how seals suggest trade.

- Practice map-based questions: Important Harappan sites and what was found there.

- Understand how archaeologists work: Terms like stratigraphy, context, and excavation methods.

- Use NCERT diagrams and case studies: They often appear in application-based questions.

|

30 videos|274 docs|25 tests

|

FAQs on Sure Shot Questions for Board Exams: Bricks, Beads and Bones - History Class 12 - Humanities/Arts

| 1. What is the significance of the title "Bricks, Beads and Bones" in the context of humanities and arts? |  |

| 2. What are some key themes explored in the study of humanities related to "Bricks, Beads and Bones"? |  |

| 3. How can students effectively prepare for exam questions related to "Bricks, Beads and Bones"? |  |

| 4. What are some sure shot questions that could appear in exams on this topic? |  |

| 5. Why is it important to understand the historical context of artifacts like bricks, beads, and bones in the study of humanities? |  |