Case Based Questions: Other Essential Elements of a Contract | Business Laws for CA Foundation PDF Download

CA Foundation - Indian Regulatory Framework: New Case-Based Questions on Other Essential Elements and Taxation Conflicts

CA Foundation - Indian Regulatory Framework: New Case-Based Questions on Other Essential Elements and Taxation Conflicts

Case Study 1: The Minor’s Consultancy Contract

Kavya, aged 17, enters a consultancy contract with Rohit’s firm, receiving ₹2 lakhs. Rohit deducts 10% TDS under Section 194J, but the Income Tax Department disputes the contract’s validity, citing Kavya’s minority.

Question: Discuss the validity of a minor’s contract under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and TDS applicability under the Income Tax Act, 1961, resolving the taxation conflict within the Indian Regulatory Framework.

Answer: Under Section 11 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, a minor (below 18) is incompetent to contract, and such agreements are void ab initio, as established in Mohori Bibee v. Dharmodas Ghose (1903), where the Privy Council held a minor’s contract unenforceable. Kavya’s consultancy contract with Rohit, at age 17, is void. Under Section 194J of the Income Tax Act, 1961, TDS at 10% applies to professional fees, but a void contract cannot trigger tax liability, as clarified in CIT v. Bharti Cellular Ltd. (2011), where invalid transactions were non-taxable. The Income Tax Department’s dispute is valid. The Indian Regulatory Framework resolves this taxation conflict by requiring Rohit to refund the TDS and recover the ₹2 lakhs via restitution under Section 65, as seen in A.V. Palanivelu Mudaliar v. Neelavathi (1937). Kavya’s CA should advise documenting her minority and coordinating with Rohit for TDS reversal, aligning the void contract with tax law to resolve the dispute.

Case Study 2: The Coerced Barter and GST

Suman, under threat of property detention, agrees to provide services worth ₹3 lakhs to Alok’s company in exchange for goods. The GST authorities demand 18% GST, which Suman disputes, claiming coercion invalidates the contract.

Question: Analyze coercion’s effect on contract validity under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and GST liability under the CGST Act, 2017, resolving the taxation conflict.

Answer: Under Section 15 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, coercion, such as threatening to detain property, renders a contract voidable at the aggrieved party’s option, as upheld in Ranganayakamma v. Kandaswami (1922), where coercion vitiated consent. Suman can rescind the barter contract. Under Section 7 of the CGST Act, 2017, barter transactions are taxable supplies, with GST (18%) on the market value of services/goods (Section 15), as confirmed in Mohit Minerals Pvt. Ltd. v. Union of India (2020). If Suman rescinds, no GST applies; if affirmed, GST is payable. The Indian Regulatory Framework resolves this taxation conflict by allowing Suman to void the contract under Section 19, nullifying GST liability, or pay GST if affirmed, with Alok claiming ITC (Section 16). Suman’s CA should advise rescinding the contract and seeking restitution under Section 72 or issuing a GST-compliant invoice if affirmed, ensuring compliance with contract and tax laws to resolve the dispute.

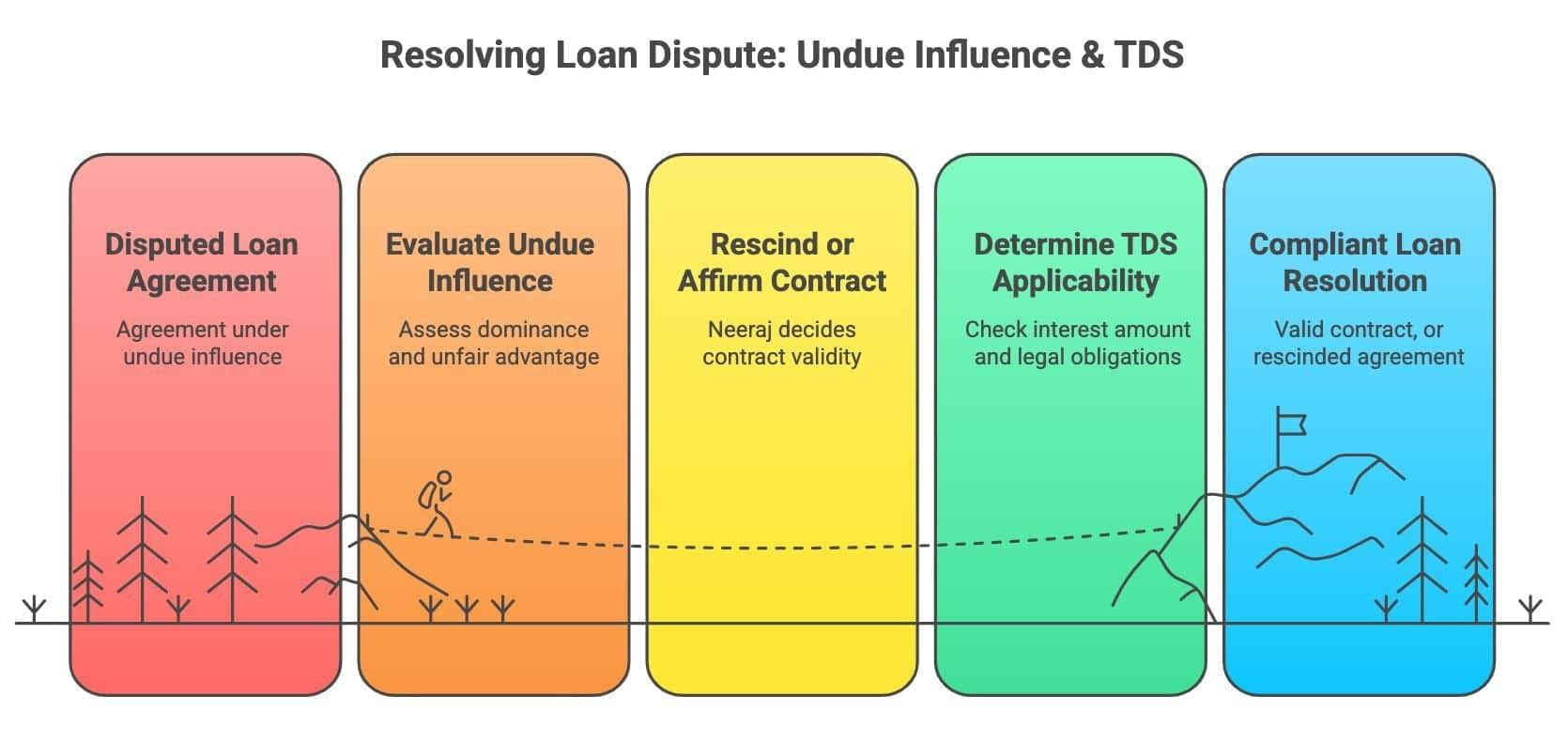

Case Study 3: The Undue Influence Loan and TDS

Neeraj, a junior employee, borrows ₹5 lakhs from his boss, Vikas, at 20% interest, influenced by Vikas’s authority. Vikas deducts 10% TDS under Section 194A, but Neeraj disputes this, claiming undue influence.

Question: Evaluate undue influence under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and TDS applicability under the Income Tax Act, 1961, resolving the taxation conflict.

Answer: Under Section 16 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, undue influence occurs when one party dominates another’s will, making the contract voidable, as seen in Mannu Singh v. Umadat Pande (1890), where a superior’s influence invalidated an agreement. Neeraj can rescind the loan agreement due to Vikas’s authority. Under Section 194A of the Income Tax Act, 1961, TDS at 10% applies to interest payments exceeding ₹40,000. If Neeraj rescinds, no interest or TDS applies; if affirmed, TDS is valid, as upheld in CIT v. Sahara India Financial Corporation (2007). The Indian Regulatory Framework resolves this taxation conflict by allowing Neeraj to void the contract under Section 19A, nullifying TDS, or accept TDS if affirmed. Neeraj’s CA should advise proving undue influence to rescind or ensuring TDS compliance if the contract persists, aligning contract validity with tax obligations to resolve the dispute.

Case Study 4: The Fraudulent Sale and GST

Priya sells a machine to Anil for ₹4 lakhs, falsely claiming it’s brand new. Anil pays, but the GST authorities demand 18% GST, which Priya disputes, citing fraud invalidates the contract.

Question: Discuss fraud’s effect on contract validity under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and GST liability under the CGST Act, 2017, resolving the taxation conflict.

Answer: Under Section 17 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, fraud, such as Priya’s false claim about the machine, makes a contract voidable at the defrauded party’s option, as established in Shri Krishnan v. Kurukshetra University (1976), where fraud justified rescission. Anil can rescind the contract. Under Section 7 of the CGST Act, 2017, GST (18%) applies to goods supplied, payable on invoice value (Section 15), as upheld in Kushal Infraproject Industries (India) Ltd. v. Union of India (2019). If Anil rescinds, no GST applies; if affirmed, Priya must pay GST. The Indian Regulatory Framework resolves this taxation conflict by allowing Anil to void the contract under Section 19, nullifying GST liability, or claim damages. Priya’s CA should advise issuing a credit note (Section 34) if rescinded or ensuring GST compliance if affirmed, aligning the contract’s voidable nature with tax obligations to resolve the dispute.

Case Study 5: The Misrepresentation Deal and ITC

Rakesh buys software from Sonia for ₹3 lakhs, believing it’s customized, based on Sonia’s innocent misrepresentation. Rakesh claims ITC, but the GST authorities demand reversal, citing a voidable contract.

Question: Analyze misrepresentation’s effect under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and ITC eligibility under the CGST Act, 2017, resolving the taxation conflict.

Answer: Under Section 18 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, innocent misrepresentation makes a contract voidable if the misled party relied on it, as seen in Bansidhar v. Bansidhar (1888), where misrepresentation allowed rescission. Rakesh can rescind the contract due to Sonia’s misrepresentation. Under Section 16 of the CGST Act, 2017, ITC requires receipt of goods/services; a voidable contract remains valid until rescinded, as clarified in Carysil Ltd. v. Union of India (2020). If Rakesh affirms, ITC is valid; if rescinded, ITC must be reversed (Section 17). The Indian Regulatory Framework resolves this taxation conflict by allowing Rakesh to rescind under Section 19, requiring Sonia to issue a credit note (Section 34), or retain ITC if affirmed. Rakesh’s CA should advise documenting the misrepresentation and coordinating with Sonia for GST adjustments, ensuring compliance with contract and tax laws to resolve the dispute.

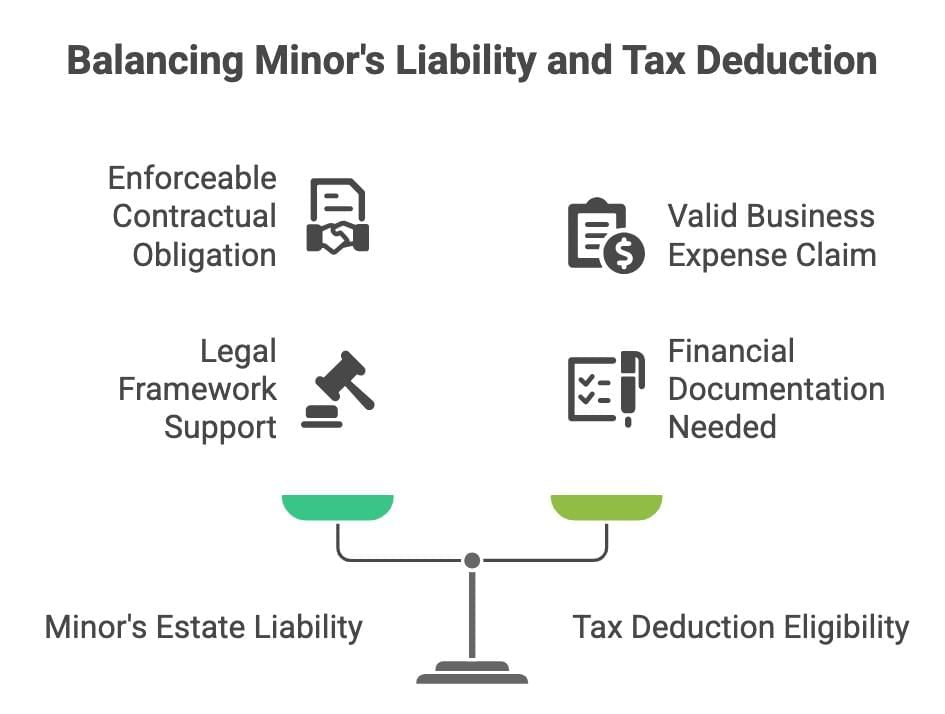

Case Study 6: The Minor’s Necessaries and Tax Deduction

Tanvi, aged 16, buys educational books worth ₹1 lakh on credit from Vikram’s store for her CA studies. Vikram claims a tax deduction under Section 37, but the Income Tax Department disallows it, citing Tanvi’s minority.

Question: Discuss a minor’s liability for necessaries under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and tax deductibility under the Income Tax Act, 1961, resolving the taxation conflict.

Answer: Under Section 68 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, a minor’s estate is liable for necessaries suited to their condition, such as educational books, as upheld in Nash v. Inman (1908), a principle applied in Chapples v. Cooper (1844) and Indian law, making Tanvi’s contract enforceable against her assets. Under Section 37 of the Income Tax Act, 1961, business expenses are deductible if incurred wholly for business, as clarified in Sassoon J. David & Co. v. CIT (1979). Vikram’s sale qualifies, and the Income Tax Department’s disallowance is invalid. The Indian Regulatory Framework resolves this taxation conflict by allowing Vikram to claim the deduction, supported by documentation of the sale and Tanvi’s asset liability. Vikram’s CA should advise maintaining records and appealing the disallowance, ensuring compliance with contract and tax laws. The minor’s liability supports the deduction, resolving the dispute.

Case Study 7: The Public Policy Agreement and GST

Ajay agrees to pay ₹2 lakhs to Meena’s firm to secure a government contract, receiving services in return. The GST authorities demand 18% GST, but Ajay disputes this, claiming the contract is void for public policy violation.

Question: Evaluate the agreement’s validity under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and GST liability under the CGST Act, 2017, resolving the taxation conflict.

Answer: Under Section 23 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, an agreement with an unlawful object, like trafficking in public offices, is void, as established in Gherulal Parakh v. Mahadeodas Maiya (1959), where agreements against public policy were unenforceable. Ajay’s payment to secure a government contract is void. Under Section 7 of the CGST Act, 2017, GST applies to supplies, but a void contract cannot trigger tax liability, as seen in Mohit Minerals Pvt. Ltd. v. Union of India (2020). The GST authorities’ demand is invalid. The Indian Regulatory Framework resolves this taxation conflict by nullifying the contract and GST obligation. Ajay’s CA should advise challenging the GST notice, proving the contract’s illegality, and seeking restitution under Section 65. Meena must refund the ₹2 lakhs, aligning the void contract with tax law to resolve the dispute.

Case Study 8: The Bilateral Mistake and TDS

Deepak and Sonia contract to sell/buy a machine for ₹5 lakhs, both mistakenly believing it’s a specific model. Deepak deducts 10% TDS under Section 194C, but the Income Tax Department disputes the contract’s validity.

Question: Discuss bilateral mistake under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and TDS applicability under the Income Tax Act, 1961, resolving the taxation conflict.

Answer: Under Section 20 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, a bilateral mistake as to the subject-matter renders a contract void, as upheld in Tarsem Singh v. Sukhminder Singh (1998), where a mutual mistake about the property invalidated the agreement. Deepak and Sonia’s contract is void due to mutual mistake. Under Section 194C of the Income Tax Act, 1961, TDS applies to contractor payments, but a void contract cannot trigger tax liability, as clarified in CIT v. Bharti Cellular Ltd. (2011). The Income Tax Department’s dispute is valid. The Indian Regulatory Framework resolves this taxation conflict by nullifying the contract and TDS obligation under Section 65, requiring Deepak to refund the payment and reverse TDS. Deepak’s CA should advise documenting the mistake and coordinating with Sonia for restitution, ensuring compliance with contract and tax laws to resolve the dispute.

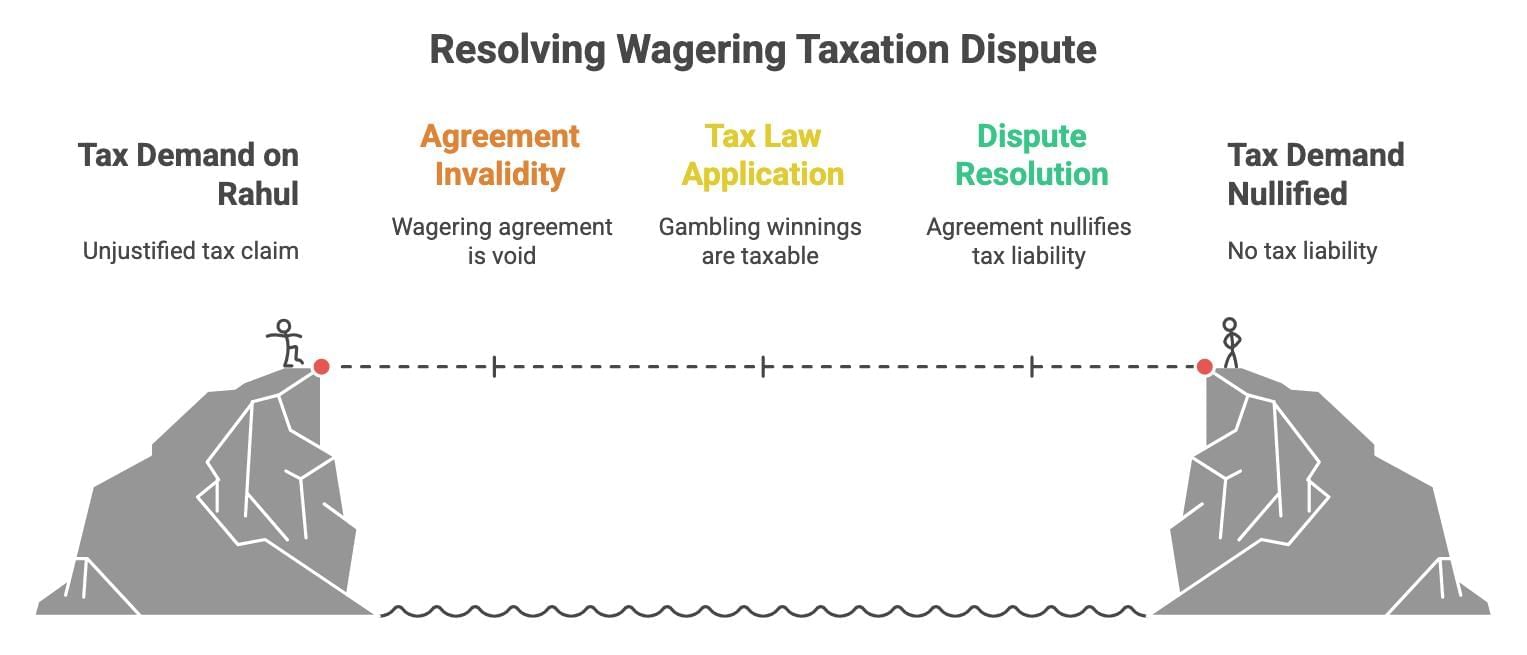

Case Study 9: The Wagering Agreement and Taxability

Rahul bets ₹3 lakhs with Kiran on a cricket match outcome, with Kiran paying taxes on the winnings. The Income Tax Department demands tax from Rahul, who disputes it, citing the agreement’s invalidity.

Question: Analyze wagering agreements under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and taxability under the Income Tax Act, 1961, resolving the taxation conflict.

Answer: Under Section 30 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, wagering agreements, like bets on cricket matches, are void, as established in Gherulal Parakh v. Mahadeodas Maiya (1959), where wagering contracts were unenforceable. Rahul’s agreement with Kiran is void. Under Section 115BB of the Income Tax Act, 1961, gambling winnings are taxable at 30%, applicable to Kiran’s receipt, not Rahul’s payment, as clarified in CIT v. K. Srinivasan (1972). The Income Tax Department’s demand on Rahul is invalid. The Indian Regulatory Framework resolves this taxation conflict by nullifying the contract and tax liability on Rahul, who can challenge the demand with evidence of the wager’s illegality. Rahul’s CA should advise documenting the agreement’s nature and appealing the tax notice, ensuring compliance with contract and tax laws to resolve the dispute.

Case Study 10: The Unsound Mind Contract and GST

Lakshmi, occasionally of unsound mind, contracts during a lucid interval to sell goods worth ₹2 lakhs to Mohan. The GST authorities demand 18% GST, but Mohan disputes it, citing Lakshmi’s mental state.

Question: Discuss contracts by persons of unsound mind under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and GST liability under the CGST Act, 2017, resolving the taxation conflict. (6 marks)

Answer: Under Section 12 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, a person usually of unsound mind can contract during lucid intervals, making the contract valid, as upheld in Amina Bibi v. Saiyid Yusuf (1922), where a lucid interval contract was enforceable. Lakshmi’s contract during a lucid interval is valid. Under Section 7 of the CGST Act, 2017, GST (18%) applies to goods supplied, payable on invoice value (Section 15), as confirmed in Mohit Minerals Pvt. Ltd. v. Union of India (2020). Mohan’s dispute based on Lakshmi’s mental state is invalid. The Indian Regulatory Framework resolves this taxation conflict by upholding the contract and GST liability. Mohan’s CA should advise paying GST and claiming ITC (Section 16), ensuring compliance with invoice requirements (Section 31). Documentation of Lakshmi’s lucid interval supports the contract’s validity, aligning with tax obligations to resolve the dispute.

|

32 videos|251 docs|57 tests

|

FAQs on Case Based Questions: Other Essential Elements of a Contract - Business Laws for CA Foundation

| 1. What is the legal standing of a contract entered into by a minor? |  |

| 2. How does coercion affect a barter agreement? |  |

| 3. What are the implications of undue influence in loan agreements? |  |

| 4. How does fraudulent misrepresentation affect the tax implications of a sale? |  |

| 5. What is the significance of public policy in contract enforceability? |  |