Firearms and Explosive Injuries - 4 Chapter Notes | Forensic Medicine and Toxicology (FMT) - NEET PG PDF Download

Autopsy Examination of Firearm Fatalities

- Purpose of Examining Clothing: The examination of clothing in cases of firearm fatalities aims to determine several critical factors, including:

- Range of Firing: Assessing how far the gun was from the victim when fired.

- Wound of Entry or Exit: Identifying whether the damage is from a bullet entering or exiting the body.

- Locating Bullets: Occasionally, finding the actual bullet within the clothing.

Procedure for Examining Clothing

- Layer-by-Layer Removal: Clothing is removed layer by layer to ensure a thorough examination.

- Documentation of Each Layer: Each layer's condition is documented, paying attention to any stains or holes present.

- Bullet Hole Recording: The number and location of bullet holes are recorded, with each hole assigned a number. Descriptions include their positions relative to the collar and pockets.

- Creases and Multiple Holes:. single bullet can create multiple holes in fabric due to creases, so this is carefully noted.

- Fibre Examination:. magnifying hand lens is used to check whether fabric fibres are turned inwards or outwards around the holes.

Further Examinations by the Forensic Science Laboratory (FSL)

- Drying Clothes: Collected clothes are dried in the shade to preserve evidence.

- Preservation: Clothes are carefully preserved in clean brown paper envelopes or bags to prevent contamination.

- Sending to FSL: The preserved clothes are sent to the forensic science laboratory for testing.

- Tests Conducted: Tests are conducted to check for the presence of blood, other biological fluid stains, and gunpowder residues on the clothing.

Photographing the Clothes

- Bullet Holes and Tracks: Clothes with bullet holes or tracks are photographed using a scale for reference to indicate size and scale.

- Infrared Photography: Infrared photography may be used to detect soot deposits on dark or coloured garments, which might not be visible through regular photography.

Examination of the Wounds

Bullet wounds should be described with care, noting both the entry and exit points.

The examination process includes:

- Wound location: Determine the position of both entry and exit wounds in relation to the top of the head, the unshod heel, the body midline, and specific anatomical landmarks.

- Wound description: Provide details about both entry and exit wounds, including their location, size, shape, and other relevant characteristics.

- Wound excision for microscopic examination: Remove the wound along with 2.5 cm of healthy skin around it and at least 5 mm of underlying tissue. This tissue sample is then placed in ethanol, labelled, and sent to the Forensic Science Laboratory (FSL).

Internal Autopsy Examination

- Apart from routine internal examinations, the most crucial aspect involves studying the path taken by bullets 9, 16, and 20. The best technique for this is taking a radiograph.

- While the probing method is used to some extent, dissection is a more effective procedure.

- Box 20.1 provides a brief checklist for the autopsy examination of a case involving firearm fatality.

Role of Radiography/X-rays in Gunshot Wounds

- Always Perform X-rays: In cases of gunshot wounds, X-rays should always be conducted to clarify essential details, including:

- Presence of the Projectile: Is the projectile present in the body?

- Location of the Projectile: If present, where is the projectile located?

- Exit and Fragments: If the projectile has exited, are there any fragments present, and where are they located?

- Type of Ammunition/Weapon: What type of ammunition or weapon was used?

- Path of the Projectile: What was the path taken by the projectile?

Problems to be Aware of:

- 22 Rimfire Ammunition: The last few inches of a 22 rimfire ammunition wound track may not show associated hemorrhage.

- Partial Exit Wound: In cases of a partial exit wound, the projectile may remain in the body even if the exit wound is visible.

- Partial Metal Jacketed Bullets: With partial metal jacketed bullets, the lead core might exit while the jacket (containing important rifling marks) stays in the body, or vice versa. Sometimes, both parts may separate within the body, and neither exits. Projectiles can also be retained in clothing.

- Poor Visibility of Components: Some projectile components, such as aluminum jackets, plastic tips, and plastic shotshell wadding, are poorly visible on standard X-rays.

- Embolisation: Projectiles may embolise, moving to different parts of the body.

- Ricochet: Projectiles can ricochet off bones inside the body, commonly off the inner skull table.

- Shotgun Pellet Spread: The spread of shotgun pellets seen on X-ray cannot determine the firing range due to the billiard-ball effect.

- Contact Shotgun Wounds: In contact shotgun wounds to the head, most pellets may exit the body.

- X-ray Magnification: The exact caliber of the projectile cannot be determined accurately due to X-ray magnification effects.

Diagnostic Tips for Identifying Bullet Wounds

- "Lead snowstorm" signifies high-speed centre-fire rifle ammunition, excluding full metal-jacketed bullets and lead slugs.

- C-shaped or comma-shaped subgaleal lead fragments found in head wounds are characteristic of 32 or occasionally 38 calibre revolver bullets.

- A "pancake" or "disc" with 2 to 4 comma-like fragments, without a "lead snowstorm," suggests a Foster shotgun slug.

- The identification of a base screw indicates the presence of a Brenneke shotgun slug.

- Removal, Marking, and Preservation of Bullets: During surgery or autopsy, bullets can be extracted using forceps with rubber tips. After removal, bullets should be dried in the shade and stored in a cardboard box. It's important to mark the doctor's initials on the base or tip of the bullet, not on the body, to preserve rifle markings.

- If a bullet is lodged in bone, the bone segment where the bullet is trapped should be cut.

- Kronlein Shot: This term refers to a specific type of injury where a large portion of the brain is herniated out of the exit wound but remains attached to it.

Tests for Gunpowder Residues

There are specific tests designed to detect contamination from blowback residues of gunpowder, which can occur when a person has recently fired a weapon. These residues are typically collected by swabbing the back of the index finger, thumb, and the spaces between the fingers using a moistened cotton swab containing a solution of five per cent nitric acid.

Limitations: The reliability of these tests is questionable because barium and antimony can be found naturally in the environment and in many common products. This raises the possibility that individuals may encounter these substances from sources other than firing a gun. As a result, most of these tests are considered inconclusive and necessitate additional forensic evidence for confirmation.

Some commonly used gunpowder residue tests include:

- Dermal Nitrate Test: This test is used to detect gunpowder particles on the hands of a shooter.

- Harrison and Gilroy Test: This test identifies specific elements or compounds like antimony, barium, and lead present in firearm discharge residue.

- Neutron Activation Analysis (NAA): NAA estimates the distance of firing and confirms the presence of substances such as barium, lead, copper, and antimony from firearm discharge residue. These elements are activated in a nuclear reactor and identified using a gamma-ray spectrometer.

- Image Analysis of Gunshot Residue (GSR): Recent techniques involve automated image analysis to measure the amount of GSR particles within and around a gunshot wound. Sample preparation and analysis procedures have been standardised for reproducibility, although preliminary findings suggest that the relationship between firing distance and GSR amount is non-linear.

- Sodium Rhodizonate Test: This test detects lead particles deposited on surfaces due to firearm discharge. Improvements have been made to enhance its forensic value, including stabilising aqueous solutions of sodium rhodizonate stored below pH 3.

Dermal Nitrate Test

The dermal nitrate test is a forensic procedure used to detect gunshot residues on the hands of individuals suspected of having fired a weapon. The test is based on the principle that gunshot residues contain nitrates, which can be detected through specific chemical reactions. Here’s a detailed explanation of the procedure and its significance:

Procedure

- The hands of the suspected individual are cleaned with gauze soaked in molten paraffin. The paraffin is allowed to cool and harden, forming a protective layer.

- The inner surface of the paraffin layer is treated with diphenylamine, a chemical reagent used in the test.

- Diphenylamine reacts with nitrates to produce a blue colour, indicating a positive test result.

Fallacies

It’s important to note that the dermal nitrate test can yield false-positive results. If any nitrogenous substance, such as urine or tobacco, is present on the hands of the individual, it can trigger a positive reaction, leading to inaccurate conclusions about the presence of gunshot residues.

Checklist for Autopsy in Firearm Deaths

Initial X-ray: Obtain an X-ray of the deceased before removing clothing to document the presence and location of projectiles or fragments.

Primer Residue Collection: Collect primer residues from the hands using a swab moistened with 10% nitric acid or adhesive tape to preserve evidence of firearm discharge.

Hand Examination: Inspect hands for trace evidence, soot, propellant grains, and blood splatter to assess the possibility of close-range firing or defensive actions.

Clothing Examination:Body Examination and Documentation:

- Carefully examine and remove clothing without cutting to preserve evidence.

- Use a dissecting microscope to analyze defects in clothing and wounds for soot and propellant residues, which can indicate firing range.

Evidence Collection:

- Examine the body and photograph wounds as needed, correlating them with clothing defects.

- After cleaning the body, take additional photographs and provide detailed wound descriptions, noting:

- Complete Wound Description: Include the internal wound track revealed during dissection.

- Wound Location: Specify relative to (a) anatomical landmarks, (b) body midline, and the distance from the heel or top of the head.

- Wound Appearance: Document size, shape, abrasion collar (width and symmetry), presence and distribution of soot and propellant (including dimensions), and any scorching or searing at the entry wound. For shotgun or smoothbore firearm wounds, describe the pellet pattern.

- Muzzle Imprint: Note any muzzle end imprint and compare it with the alleged weapon if available at the crime scene or later provided.

- Projectile Path: Describe whether the projectile is lodged or exited relative to the entry wound and note the general direction of the wound track.

- Recovered Projectiles: Describe any recovered projectiles or fragments.

- Trace wound tracks and recover projectiles during dissection.

- Collect propellant grains from the skin surface or wound track.

- Recover projectiles carefully to avoid scratching, using rubber-tipped forceps or gloved fingers instead of toothed forceps.

- Sample shotgun pellets and all wadding, if present.

- Collect blood for grouping and blood/tissue samples for toxicology analysis.

This systematic approach ensures comprehensive evidence collection and documentation for accurate forensic analysis of gunshot wounds.

Forensic Tests for Gunshot Residue (GSR) and Firing Range Estimation

Paraffin Test Procedure:

- Mop the suspect’s hands with gauze soaked in molten paraffin, allowing it to cool and harden.

- Treat the inner surface of the paraffin cast with diphenylamine. A blue color indicates a positive result for nitrates.

- Limitations: The test is non-specific, as it reacts with any nitrogenous substances (e.g., urine, tobacco), leading to potential false positives.

Harrison and Gilroy Test:

- This test detects elements such as antimony, barium, and lead in firearm discharge residue, aiding in identifying individuals who may have fired a weapon.

Neutron Activation Analysis (NAA):

- Used to estimate firing distance and confirm firearm use by detecting elements like barium, copper, and antimony in GSR from the primer.

- The sample is activated in a nuclear reactor, and the resulting gamma rays are analyzed using a spectrometer for precise identification of these elements.

Image Analysis of Gunshot Residue on Entry Wounds:

- A newer technique involving automated image analysis (IA) to quantify GSR particles (number and area) within and around a gunshot wound.

- Standardized sample preparation and IA procedures enhance measurement reproducibility.

- Preliminary findings show a non-linear relationship between firing range and GSR deposition, with high variability in GSR amounts for repeated shots at the same distance (up to 20 cm).

Sodium Rhodizonate Test:

- Detects particulate lead deposited on surfaces from firearm discharge.

- Improvements to Address Limitations:

- Aqueous sodium rhodizonate solutions are stabilized below pH 3, converting to rhodizonic acid, extending solution half-life from ~1 hour to ~10 hours.

- Pretreat the test area with a tartrate buffer (pH 2.8) to prevent formation of a non-diagnostic purple complex, ensuring the desired scarlet complex forms.

- The scarlet complex turns blue-violet upon treatment with 5% HCl, confirming lead presence, while the purple complex decolorizes, wasting lead and contributing to fading issues.

- Fading of the blue-violet complex is prevented by removing excess HCl with a hairdryer once the color fully develops.

These tests provide critical forensic evidence for identifying firearm use and estimating firing range, though each has specific considerations to ensure accuracy and reliability.

Medico-Legal Questions Regarding Firearm Injuries

When investigating a death caused by a firearm injury, it is crucial to address specific questions for both legal and medical reasons. These questions help determine the circumstances surrounding the injury and the type of firearm involved.

Types of Firearms

A careful analysis of the entry wounds, coupled with knowledge of different firearm classifications, can aid in identifying the type of firearm used in the incident.

- A detailed description of the entry wounds is essential for determining the firing range in cases of gunshot and shotgun wounds.

Direction of Firing

- Radiographic examination is the most reliable way to determine the direction of firing. However, it is also acceptable to examine the wound directly. The autopsy dissection method is considered more trustworthy than direct examination.

Cause of Death

- Death usually occurs due to injuries sustained by vital organs along the bullet's path.

Accident, Suicide or Homicide?

Firearm-related deaths are a significant public health concern, ranking as the ninth leading cause of death in the USA. From 1962 to 1994, deaths from firearms increased by 130 percent, rising from 16,720 to 38,505. If this trend continues, firearm-related injuries could become the leading cause of death, surpassing motor vehicle crashes. Firearm-related fatalities include:- Homicide

- Suicide

- Unintentional death

- Deaths during legal intervention

- Deaths of undetermined origin

In 1994, suicide and homicide accounted for 94 percent of firearm deaths in the USA. The increase in overall firearm-related mortality closely followed the pattern of firearm-related homicide. Although suicide rates were high and rising, they varied less than homicide rates. Rates for unintentional deaths, deaths during legal intervention, and deaths of unclear intent are low and have generally declined. Firearm-related deaths affect all demographic groups, with the most significant increases among:

- Teens aged 15-19

- Young adults aged 20-24

- Older adults aged 75 and older

From 1990 to 1994, young people aged 15-24 experienced the highest rates of firearm-related mortality. Increases in firearm-related homicide occurred across all race-sex groups. For the elderly, firearm-related suicide rates were notably high, with increases observed in all groups except for Black women, where the number of suicides was too low to produce stable rates. While this data highlights at-risk groups, there are significant knowledge gaps regarding prevention strategies.

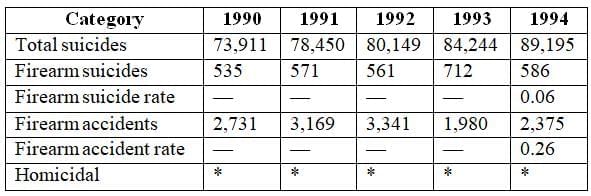

In India, the prevalence of illicit small arms and insufficient policing have compromised human rights, weakened democratic institutions, and intensified ethnic, religious, economic, and political tensions among citizens. Law enforcement faces challenges in controlling violence, particularly during elections when armed groups associated with politicians are active. The intimidation by these criminal factions is exacerbated by the restrictive legal framework on firearm ownership, limiting private citizens' ability to defend themselves. Statistics on suicides and firearm accidents in India from 1990 to 1994.

Certain key points can help determine whether a specific firearm injury is accidental, suicidal, or homicidal:

- Accidental: Wounds may occur anywhere on the victim's body.

- Suicidal: Wounds are often singular and typically found on vital areas of the body, easily accessible to the victim, such as the temple or the left side of the chest.

The firing range in a suicidal death is typically at close range, and the victim may leave a suicide note nearby. The weapon may be held tightly by the victim, often due to cadaveric spasm. It is also noted that a left-handed victim will usually fire on the left side of the head. Observations from literature regarding suicidal firearm deaths include:

- The majority of suicides (including gunshot suicides) do not leave a suicide note.

- A contact wound suggests suicide rather than an accident.

- With rifle and shotgun wounds to the trunk, the trajectory can indicate suicide. If the weapon's butt is on the ground and the body leans over it, the trajectory will be downward (not upward). If the right hand reaches for the trigger, the body will rotate, causing the trajectory to run from right to left (and vice versa for the left hand).

Suicide Handgun Wounds

- Suicide handgun wounds primarily occur in the head (80%), followed by the chest (15%) and abdomen (less common).

- Within the head, the most common sites, in order, are the temple, mouth, undersurface of the chin, and forehead.

- An unusual location for the wound may suggest homicide.

Suicidal Shotgun Wounds

- Suicidal shotgun wounds show the same site preference as handguns.

Rifle Wounds

- Rifle wounds distribution: head (50%), chest (35%), abdomen (15%).

Suicides and Firearm Accidents in India, 1990-1994

* India reported its homicide statistics as "not reasonably available"

* India reported its homicide statistics as "not reasonably available"

Suicide by Multiple Gunshots

- Rare but possible.

- Victim might test fire the weapon before the final shot.

- In about 20% of cases, the weapon is found in the victim's hand.

- Occasionally, an orange-brown iron stain may appear on the palm.

Signs of Gunshot Wounds

- High-velocity impact blood spatter may be present on the back of the hand.

- The hand gripping the muzzle may show soot on the fingers and palm due to the muzzle blast.

- With revolvers, soot may also be found on the palm because of cylinder blast.

Contact Wounds

- Wounds from medium and large calibre weapons on cotton or cotton blend cloth often cause cruciform tearings.

- Synthetic materials typically exhibit burn holes with melted edges.

- Tear damage is less prominent with 22 rimfire ammunition.

- A grey to black rim of "bullet wipe" may surround the entrance hole.

Homicidal Wounds

- Homicidal wounds are generally located on vital areas of the body that the victim cannot access.

- The firing range can vary significantly.

Fake Firearm Wounds

- Fake firearm wounds can occur for various reasons, including malicious intent, attempts to evade conscription, or other motives.

- These injuries are typically inflicted on non-vital areas of the body, resulting in minimal harm to the individual.

- Understanding the underlying reasons for these injuries may necessitate the expertise of clinical psychologists and psychiatrists.

- According to a spokesperson from Scotland Yard, a significant portion (70 percent) of firearm offences related to gun crime in London’s black communities involve replica guns that have been modified to fire live ammunition, often leading to fatalities.

- In Chris Summers' BBC Online News Report titled 'Killed by Fake Gun', a particular case is examined that was resolved through the confession of the perpetrator. The criminal claimed that the death was accidental and unintentional.

Position of Weapon

- The following points can be reiterated, particularly regarding the position of the weapon in cases of firearm fatalities: 9, 14, 16, 20.

- In suicides, the weapon is often still firmly held in the victim's hand due to cadaveric spasm. Common sites for suicidal wounds include the mouth, head, and front of the chest. It is rare for a woman to commit suicide using a firearm. [Citation needed for verification]

- In accidental cases, the weapon is typically found at the scene of the incident.

- No weapon is discovered at the scene in cases of homicide.

- It is important to determine how the person accessed the gun and its ammunition. For long-barreled weapons, it must be established whether the deceased could have fired the weapon, which requires measuring arm span, among other factors.

Time of Survival Post-Injury

- Gunshot wounds to vital areas like the brain or heart can result in instant death.

- Injuries to other parts of the body might allow victims to live for a considerable period.

- Victims may be capable of moving and taking crucial actions, such as reaching a hospital independently before succumbing to their injuries.

Medicolegal Significance of Bullets

- Bullets can be categorized as crime bullets, test bullets, or exhibit bullets.

- A crime bullet is one found during surgery or autopsy, from a victim who is either alive or dead.

- A test bullet is fired from a suspected weapon in a crime, into a gunny bag inside a sealed wooden box for comparison purposes.

- This comparison, done with a microscope, helps identify the weapon used in the crime and applies only to rifled firearms.

- An exhibit bullet is a crime or test bullet presented in court as evidence.

Crime Scene Instructions

- Evidence Preservation: Handle the body as little as possible to avoid losing important evidence. The victim's hands may be placed in a paper bag to keep trace evidence safe.

- Body Transport: Transport the body using clear plastic sheeting or a body bag to preserve evidence and prevent contamination.

Explosives and Explosive Injuries

- Synonyms: Explosion injury, bombing, terrorism, firework injury, industrial fuel eruption, mine explosion, land mine, hand grenade, blast injury, radiological contamination, biological contamination, terrorist attacks, primary blast injury, secondary blast injury, tertiary blast injury.

Overview: Due to the increase in terrorist attacks, disaster response teams need to be familiar with the medical conditions associated with explosion injuries and be prepared to assist those affected. Bombs and explosions can cause specific patterns of injury that require targeted medical attention. Survivors often experience:

- Penetrating injuries and blunt trauma as the most common types of injuries.

- Enclosed Spaces: Explosions in confined areas such as mines, buildings, or large vehicles typically result in higher rates of injury and mortality.

Factors Influencing Injuries: The severity and type of injuries from explosions depend on several factors:

- Materials and Quantity: The types and amounts of materials used in the explosion.

- Environment: The surrounding environment where the explosion occurs.

- Delivery Method: How the explosive is delivered, such as through a bomb.

- Distance: The distance of the victim from the blast site.

- Barriers and Dangers: Any protective barriers or environmental hazards present.

Challenges in Emergency Care: Since explosions are not everyday occurrences, injuries resulting from blasts can pose unique challenges in diagnosis and treatment during emergency medical care.

Taxonomy of Explosives

Explosives are categorized into two main types: high-order explosives (HE) and low-order explosives (LE).

High-Order Explosives (HE)

- High-order explosives are known for producing a powerful supersonic shock wave upon detonation.

- Common examples of high-order explosives include: TNT (Trinitrotoluene)C-4SemtexNitroglycerinDynamiteAmmonium Nitrate Fuel Oil (ANFO)

Low-Order Explosives (LE)

- Low-order explosives generate a subsonic explosion and do not create over-pressurization.

- Examples of low-order explosives include: Pipe bombs Gunpowder Petroleum-based bombs such as Molotov cocktails, and aircraft used as guided missiles

- High-order and low-order explosives lead to different types of injuries due to the nature of their explosions.

Types of Explosive Bombs

- Explosive and incendiary bombs are classified based on their origin and method of production.

- Manufactured explosives are standard military weapons that are produced in large quantities and tested for quality and reliability.

- Improvised explosives are created in small numbers or involve repurposing devices for unintended uses, such as converting a commercial aircraft into a guided missile.

Manufactured and Improvised Explosives

- Manufactured military weapons primarily consist of high-order explosives but may also include low-order explosives in certain cases.

- Terrorist groups may utilize a range of available options, including illegally obtained manufactured bombs or improvised explosive devices (IEDs), which can be classified as high-order, low-order, or a combination of both.

- The injuries resulting from manufactured and improvised bombs can be significantly different due to the variations in their construction and the types of explosives used.

Blast Injuries

Mechanisms of Injuries

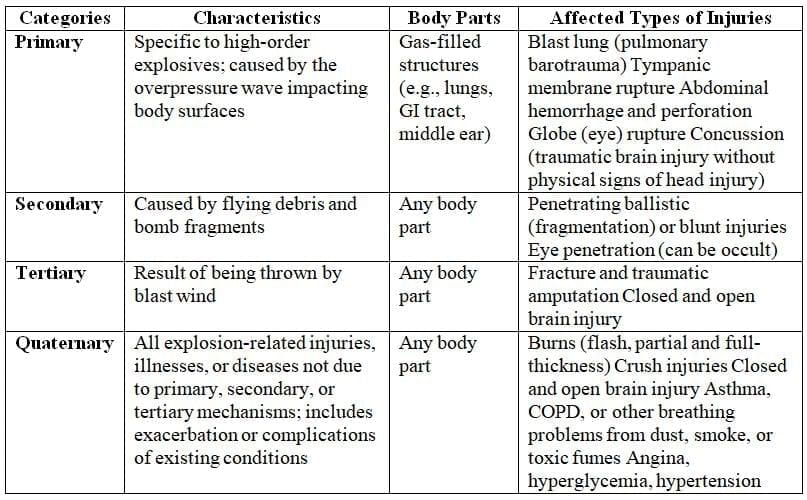

Types of Blast Injuries:

- Primary Injuries: Caused by the blast wave, which is the intense pressure surge from a detonated high explosive (HE). These injuries involve physical and physiological changes due to the direct impact of overpressure. It's crucial to distinguish between the HE blast wave (over-pressure) and the blast wind (forceful flow of superheated air), which can occur with both high and low explosives.

- Secondary Injuries: Result from flying debris and bomb fragments.

- Tertiary Injuries: Occur when bodies are propelled by the blast wind, leading to fractures and traumatic amputations.

- Quaternary Injuries: Include all explosion-related injuries, illnesses, or conditions not caused by primary, secondary, or tertiary mechanisms. This category encompasses burns (flash, partial, and full-thickness), crush injuries, and exacerbation of existing health issues such as asthma, COPD, or cardiovascular problems.

Low-Order Explosives: These explosives do not create the same overpressure wave as high explosives. Instead, they cause injuries primarily from:

- Ballistics (fragmentation): Injuries caused by flying fragments.

- Blast wind: The forceful flow of air, not the blast wave.

- Thermal effects: Injuries due to heat.

Eye Injuries from Blasts:

- About 10% of blast survivors experience serious eye injuries, often from perforations caused by high-velocity projectiles.

- Initial symptoms may be minimal, but later symptoms can include:

- Eye pain or irritation

- Foreign body sensation

- Changes in vision

- Swelling or bruising around the eyes

Findings in Eye Injuries:

- Decreased visual acuity

- Hyphaema (blood in the anterior chamber of the eye)

- Globe perforation

- Subconjunctival haemorrhage

- Foreign bodies or lacerations of the eyelid

Factors Influencing Blast Injury Severity:

- Amount and type of explosive material used

- Environment of the explosion (e.g., presence of protective barriers)

- Distance of the victim from the explosion

- Method of delivery if a bomb is used

- Other environmental hazards

Structure of a Bomb:

- A bomb typically consists of a solid container filled with explosive material (usually 2-10 kg for a terrorist bomb), which may also include projectiles such as nails and metal fragments.

- A detonator or fuse initiates the explosion.

- Upon detonation, the bomb releases a large amount of energy in the form of heat and kinetic energy, creating a powerful air blast that can injure individuals nearby.

- The bomb's container shatters into shrapnel, and objects within the bomb can fragment, acting as secondary missiles causing further harm.

Historical Context:

- Between 1991 and 2000, there were 885 terrorist attacks globally involving explosives.

- Notable incidents include the 2005 London subway bombings, the 1995 bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, and the September 11, 2001, airplane attacks in New York City and Washington DC.

- Industrial accidents, such as those in mining operations and fuel transportation, also contribute to injuries and fatalities from blasts.

In various regions around the world, military incendiary devices such as land mines and hand grenades pose a serious threat by contaminating abandoned battlefields. These devices can result in a significant number of civilian casualties. During times of war, injuries caused by these explosions often surpass those caused by gunfire, impacting many innocent civilians.

Mechanisms of blast injury

Victim of blast injury death. Blackening of palmar aspect of hand

Victim of blast injury death. Blackening of palmar aspect of hand

Types of Blast Injuries

Blast injuries are typically categorized into four types:

- Primary blast injuries occur due to the direct impact of blast overpressure on tissues. These injuries primarily affect air-filled structures like the lungs, ears, and gastrointestinal (GI) tract, as air is more compressible than water.

- Secondary blast injuries result from flying debris striking individuals.

- Tertiary blast injuries happen during high-energy explosions when a person is propelled through the air and collides with other objects.

- Miscellaneous blast-related injuries encompass any other injuries resulting from explosions. For example, the impact of two jet planes hitting the World Trade Center generated a low-order pressure wave, but the resulting fire and building collapse led to thousands of fatalities.

|

70 docs|3 tests

|

FAQs on Firearms and Explosive Injuries - 4 Chapter Notes - Forensic Medicine and Toxicology (FMT) - NEET PG

| 1. What are the common tests for detecting gunpowder residues on a person? |  |

| 2. What medico-legal questions arise from firearm injuries? |  |

| 3. What are the primary types of blast injuries associated with explosives? |  |

| 4. How is the taxonomy of explosives categorized? |  |

| 5. What guidelines should be followed at a crime scene involving firearms? |  |