Forensic Psychiatry - 2 Chapter Notes | Forensic Medicine and Toxicology (FMT) - NEET PG PDF Download

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia, a form of functional psychosis, is characterized by disordered thinking and a disconnection between thoughts and emotions, often described as a "split personality." For example, a schizophrenic individual might recount with pleasure or fascination an act of violence, such as attacking or killing someone, showing a stark emotional disconnect.

Clinical Manifestations

Schizophrenia manifests in two distinct phases: early and late.

Early Phase

The early phase typically features one of the following dominant symptoms:

Thought Disorders: Individuals misinterpret reality due to hallucinations, illusions, or delusions, retreating into a personal, detached world.

Emotional Instability: Behavioral changes occur, such as becoming withdrawn, depressive, or violent.

Late Phase

As the condition progresses, individuals become increasingly detached from their environment, exhibiting:

- Lack of motivation or ambition

- Abandonment of hobbies

- Loss of interest in social connections

- Indifference to surroundings

Classification

Schizophrenia is categorized into four main subtypes, each with distinct characteristics:

Simple Schizophrenia: Patients display all typical symptoms but react to significant events with indifference, as if unaffected.

Hebephrenic Schizophrenia: Marked by severe thought disorganization due to hallucinations, illusions, and delusions. This may lead to impulsive actions, including crimes, which can occur unpredictably, even without conscious intent during the act.

Case Example: A patient, influenced by voices commanding them to kill their mother, hesitated initially but later acted on the impulse without hearing the voices, silently killing her with a razor.Paranoid Schizophrenia: Patients retain much of their original personality but experience distorted thinking, with persecutory or grandiose delusions and hallucinations. This creates a warped perception of reality. For example, Othello Syndrome, a form of morbid jealousy, may lead to delusions of a partner’s infidelity, potentially resulting in assault or murder.

Catatonic Schizophrenia: Characterized by mood disturbances, physical rigidity, stupor, agitation, bizarre posturing, or repetitive mimicking of others’ movements or speech. Patients risk malnutrition, exhaustion, or self-harm.

Undifferentiated Schizophrenia: Patients exhibit characteristic symptoms of schizophrenia but do not fit neatly into the other subtypes.

Clinical Features

Patients may present with:

- Delusions of reference (believing neutral events are personally significant)

- Delusions of persecution (feeling targeted or threatened)

- Delusions of grandeur (exaggerated self-importance)

- Paranoid delusions

These symptoms may drive individuals to commit crimes, often not impulsively but after prolonged complaints and planning. Because much of their original personality remains intact, their actions may not immediately suggest insanity or require a formal certificate of mental illness.

Paranoid State

A paranoid state is another type of functional psychosis where individuals experience delusions, with or without hallucinations, but maintain intact mood and thinking, with well-preserved personality.

Clinical Manifestations

This condition typically emerges in middle age or later and is divided into two types:

- Paranoia: Onset between ages 25–40, more common in males. This rare mental illness involves gradually developing, systematized delusions of persecution with significant criminal implications.

- Paraphrenia: Onset around age 45 or later. This rare condition features systematized delusions, ideas of reference, and vivid auditory hallucinations.

Medicolegal Importance

- Delusions of persecution may lead to conflicts with neighbors, prompting police involvement.

- Patients may publicly challenge court or police decisions, believing they are unjustly targeted.

Diagnosing Mental Illness and Issuing Certificates

Diagnosing a clear case of mental illness is relatively straightforward. However, challenges arise primarily in the early stages of mental health issues. This emphasizes the importance of a thorough assessment when any mental health concern is suspected. The assessment should include the following examination scheme:

Preliminary Details

- Record the individual's name, age, sex, marital status, education, occupation, income, address, religion, and socio-economic background.

- Document information about the accompanying person, including their name, age, sex, and address, regardless of whether they live with the individual.

- Record and evaluate statements from both the individual and the accompanying person.

- Note two identification marks, such as moles, birthmarks, etc.

Presenting Complaints

- While noting down the presenting complaints, pay close attention to the following aspects:

- When did the current illness begin?

- How long have the symptoms been present, and how have they changed over time?

- Are there any factors that trigger, worsen, maintain, or relieve the condition?

History of Present Illness

- Record when the patient was last in good health and how the symptoms have evolved since then.

- Include details about:

- Any thoughts of self-harm or past suicide attempts

- Sleep issues such as insomnia, hypersomnia, or sleep apnea

- Changes in appetite

- Sexual function and any related concerns

Past History

- Document any significant or minor illnesses and treatments from the past.

- Ask about any history of alcoholism or drug abuse.

Family History

- There might be a background of chorea, epilepsy, or severe mental illness in the patient's parents or siblings.

- Various mental illnesses can be familial, shaped by both genetic factors and environmental influences, as evidenced by family members.

Personal History

- Gather detailed information about the patient's childhood, including their play history, friendships, puberty, and for females, their menstrual and obstetric history.

- Inquire about any head injuries, drug addiction, and significant issues such as domestic problems and emotional distress.

- Record details about the premorbid personality, including interpersonal relationships, attitudes towards self and others, work and religious beliefs, moral values, mood, habits, fantasy life, and leisure activities.

Physical Examination

- The patient may exhibit abnormalities in the shape of the head or body.

- Their clothing may be inappropriate for the situation.

- An irregular walking pattern (gait) could be observed.

- A tongue that appears thickened (furred) and skin that is dry might be present.

- On the other hand, moist palms and soles could also be noticeable.

- Signs such as a rapid pulse and elevated body temperature may be evident.

Examination of Mental Status/Conditions

Various tests can assist in diagnosing the condition. Recommended assessments include:

- Memory Test: Inquiring about the day, date, time, name, and names of relatives, with the expectation of unclear responses.

- Reasoning and Judgment: Simple mathematical questions that the patient may find difficult to answer.

- Handwriting: Typically observed as messy rather than tidy.

- Speech: Monitoring aspects such as rate, volume, tone, flow, and rhythm of speech.

- Conduct: Noting any lack of response to stimuli or behaviors that seem disconnected from events.

General Appearance and Behaviour Assessment:

General appearance and behaviour are evaluated by considering:

- Physical attributes such as physique, build, height, weight, and hygiene.

- Gait and posture.

- Behavioural aspects including cooperation, hostility, evasiveness, combativeness, excitement, involuntary movements, and restlessness.

- Presence of catatonic signs and the nature of eye contact.

- Ability to establish rapport and indications of hallucinations, like talking to oneself or making unusual gestures.

Cognition Assessment:

- Cognition assessment involves evaluating consciousness, orientation, attention, concentration, and abstract thinking abilities.

- Insight assessment measures the patient’s awareness and understanding of their condition.

- Judgment assessment examines the capacity to comprehend situations and respond appropriately.

Investigations

- Complete medical toxicological screening tests.

- Drug levels.

- Electrophysiological tests.

- Brain imaging tests.

- Neuroendocrine tests.

- Genetic tests.

- Sexual disorder investigations, and other relevant investigations.

Diagnostic Formulation

- After a thorough psychiatric evaluation, diagnosis and differential diagnostic assessments are conducted along with a comprehensive treatment plan.

Certification

- A certification of mental illness by a doctor based on a single examination is insufficient.

- Recommendations for issuing a certificate for mental illnesses are as follows:

- Conduct three consecutive examinations on three occasions.

- Describe the actual clinical picture in the certificate.

- Provide clear reasons for the diagnosis made.

- Rule out the possibilities of feigned insanity.

Feigned Insanity

Feigned insanity involves an individual pretending to be mentally ill.

Purpose

- To evade capital punishment in criminal cases.

- To escape from business transactions or legal agreements.

- To withdraw from military service.

It is up to doctors to detect and report cases of feigned insanity. Observation should continue for at least 10 days, although this period can be extended with a magistrate's approval.

Key Characteristics

- The onset of feigned insanity is often sudden and may be driven by an underlying motive.

- The individual exhibits signs of insanity only when under observation.

- The symptoms do not align with a specific type of insanity.

- Deceiving others can lead to exhaustion.

- Individuals pretending to be ill typically maintain their personal hygiene and eat well.

- A malingerer often feels frustrated by frequent examinations.

- Examples of feigned conditions include deafness and mutism.

Restraint of Mentally Ill Individuals

Restraint of mentally ill or insane individuals refers to the practice of keeping dangerous individuals with severe mental health issues securely under control in a mental hospital. The Mental Health Act, 1987 updated the laws concerning the treatment and care of mentally ill individuals, enhancing provisions related to their property and affairs. There are primarily two types of restraint: immediate restraint and admission to a psychiatric hospital.

Immediate Restraint

Immediate restraint involves confining the patient without delay. The following situations may indicate the need for immediate restraint:

- When a person exhibits severe mental incapacity, posing a serious risk to themselves or others.

- Delirium caused by underlying medical issues such as infections or metabolic problems.

- Delirium tremens.

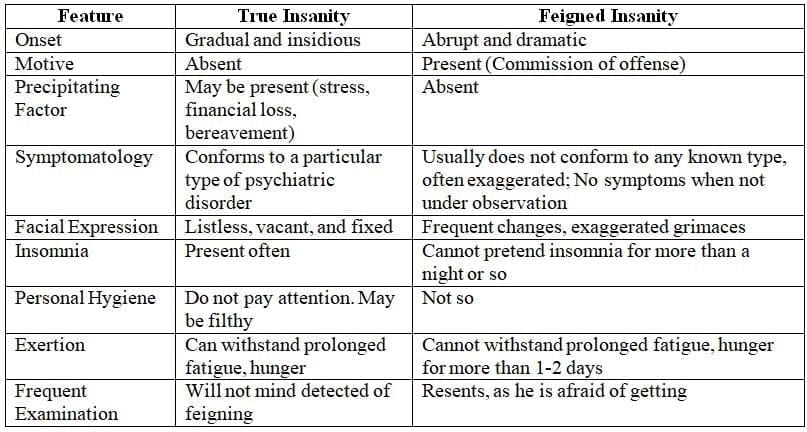

True vs. False Insanity

- True Insanity: Develops gradually and subtly, without a clear motive. Symptoms align with a specific psychiatric disorder and may include insomnia, neglect of personal hygiene, and the ability to endure extended fatigue and hunger. Individuals do not mind being detected, and symptoms may disappear when not under observation.

- False Insanity: Appears suddenly and dramatically, often with a motive related to committing an offense. Symptoms are exaggerated, not fitting any known disorder, and include frequent changes in behavior. Insomnia is not maintained for more than a night, personal hygiene is typically intact, and individuals cannot tolerate extended fatigue and hunger for more than 1-2 days. They resent being detected due to fear of exposure.

Methods: The methods for restraint involve safely confining the individual in a room, ideally with consent from guardians or authorized individuals. Consent is not required if there is no time to obtain it. However, the individual should be released once they are no longer a danger.

Differences between true and false insanity

Ways to Get Admitted to a Psychiatric Hospital

There are several legally approved methods for admitting individuals to a psychiatric hospital. These methods include:

- Voluntary or Direct Restraint

- Reception Order on Petition

- Reception Order Other than on Petition

- Reception after Judicial Inquisition

- Reception of Mentally Ill Criminals

- Reception of Escaped Mentally Ill Individuals

Voluntary or Direct Restraint

This method involves an individual with mental health issues voluntarily requesting admission and treatment at a psychiatric hospital. The process includes the following steps:

- Written Request: The individual submits a written request for admission directly to the officer in charge of the hospital.

- Assessment: The request is assessed to determine the necessity of inpatient care.

- Consent from Visitors: The individual must obtain consent from two appointed visitors of the hospital. These visitors are responsible for confirming that the individual requires inpatient care and treatment.

Petition for Admission: Steps Involved

A person struggling with mental illness can be admitted to a mental health facility through a legal process that involves several important steps:

- Petition Submission:. relative or friend who has been caring for the individual for at least 14 days must submit a formal petition to the magistrate. This petition requests the admission of the person to a mental hospital.

- Required Documents: Along with the petition, several crucial documents need to be submitted to support the request:

- Medical Certificate:. certificate from a registered medical practitioner is necessary, stating that the patient requires mental treatment in a hospital.

- Examination Certificate:. certificate from a medical officer who has examined the patient within the last 7 days is required, confirming the need for hospitalization.

- Fitness for Travel:. doctor’s certificate indicating the patient’s physical fitness for travel is also necessary.

Magistrate's Role: Once the petition and documents are submitted, the magistrate will review them and may issue an order for reception. In some cases, the magistrate may personally examine the patient before making a decision.

Validity of Order: The order issued by the magistrate for reception is typically valid for 30 days, allowing for the necessary arrangements to be made for the patient’s admission to the mental health facility.

Reception Order Other Than on Petition

Following are the indications and procedures.

- Individualswho may pose a risk to themselves or others:

- Police officers are authorised to arrest such patients and bring them before a magistrate.

- The magistrate can issue a reception order directly.

- If there is any doubt, the magistrate may send the patient for a medical examination.

- The order is issued only if the patient is certified as mentally ill and dangerous.

- Individualswho are not receiving adequate care:

- Police officers can present individuals with mental illness who are not properly cared for or are cruelly treated by their relatives to the magistrate.

- A reception order can be sanctioned in such cases.

Reception after Judicial Evaluation

- When a person with substantial assets is found to be mentally ill, the high court or district court has the authority to order a judicial evaluation. Based on the findings, the court can facilitate:

- Admission to a Mental Hospital: The individual may be admitted to a mental health facility for proper care and treatment.

- Property Management: The court can ensure that the individual's property is managed appropriately to protect their interests.

- Fee Recovery Arrangements: Arrangements can be made to recover necessary fees from the income generated by the individual's property. This process will be under the supervision of the court to ensure transparency and legality.

Reception of Mentally Ill Criminal

- This process involves individuals who are mentally ill and have either committed a crime or have developed mental illness after being incarcerated. In such cases, the presiding officer of the court will issue an order for the reception of these individuals to ensure they receive appropriate care and treatment.

Reception of the Escaped Mentally Ill

A police officer or any staff member of the hospital can readmit such a patient to a mental hospital.

Discharge of Mentally Ill from Psychiatric Hospital

Discharging a patient from a mental hospital depends on several factors, including:

- Recovery or cure of the patient

- Request from the individual who initiated the discharge petition

- Order from an authority, ensuring proper care by relatives

- Judicial requisition confirming the patient 's sanity

- Intent to discharge by the voluntary or direct boarder

Responsibilities of an Insane Individual

The legal obligations of a sane person for their actions or lack thereof, and the associated punishments under the law. The responsibilities of an insane person are considered under two categories:

- Civil responsibilities

- Criminal responsibilities

Civil Responsibilities

Civil responsibilities relate to the following:

- Management of property: According to Sections 50, 51, 53, and 54 of the Mental Health Act, 1987, the court can oversee the property of an insane individual by appointing a manager. This occurs only when a friend or relative requests this, a judicial inquiry is conducted, and it is proven beyond a reasonable doubt that the person is mentally unsound.

- Contracts: Under Section 12 of the Indian Contract Act (IX) of 1872, any contract with a mentally ill person is considered invalid. However, it is valid if made during a lucid interval. If insanity develops later, it does not automatically invalidate the contract. Furthermore, if one party was unaware of the other party's mental illness at the time of signing, the court may declare the contract invalid.

- Marriage and divorce: As per the Divorce Act of 1869, a marriage is null and void if one partner is mentally ill at the time of the marriage. This means the marriage is legally regarded as never having occurred, even if it was consummated afterwards. However, if one spouse becomes mentally ill after the marriage, it does not lead to nullity but may be grounds for divorce.

- Competency as a witness: According to Section 118 of the Indian Evidence Act, a mentally ill person cannot serve as a witness unless they are in a lucid interval. It is up to the judge to decide if the person is in such an interval.

- Validity of consent: Under Section 90 of the IPC, consent given by a mentally ill person is invalid in all circumstances.

- Testamentary capacity: Under the Indian Evidence Act, a will can be contested and is not valid unless it can be shown that the testator is mentally sound (compos mentis).

Criminal Responsibilities

Criminal responsibility in law refers to the duty to face punishment for one's actions. The legal system presumes that individuals are sane and accountable for their actions unless proven otherwise. Conversely, those deemed insane are not held accountable for their actions.

Section 84 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) states that a person is not committing an offence if, at the time of the act, they are suffering from a mental disorder that prevents them from understanding:

- The nature of their act

- That what they are doing is wrong or against the law

This provision is similar to McNaghten’s Rule in English law.

Legal Test for Insanity

- The legal test for insanity aims to determine if an individual is responsible for a crime based on the presence of a mental illness or defect at the time of the offence.

- To establish this defence, three key factors must be demonstrated in court:

- Existence of Mental Illness or Defect: There must be evidence of a mental illness or defect affecting the individual's mental capacity.

- Timeliness: The mental illness or defect must have been present at the time the crime was committed.

- Lack of Awareness: The condition should prevent the individual from recognising that their actions were wrong or illegal.

Insanity and Murder

- When a person with a mental disorder, such as schizophrenia, commits murder, legal outcomes can vary under Section 84 of the IPC.

- Examples of different types of killers include:

- Psychotic killers: Individuals with severe mental disorders who commit murder.

- Sexual killers: Murderers motivated by sexual factors.

- Psychopathic killers: Individuals, such as hired assassins, who commit murder for personal gain.

- Jealous killers: Individuals driven by intense jealousy, such as those experiencing Othello syndrome.

- Alcoholic killers: Individuals whose criminal behaviour is linked to alcohol abuse and issues like infidelity.

Insanity and Other Legal Defences

- Somnambulism: Crimes committed while sleepwalking are generally considered unintentional and not subject to punishment.

- Hypnosis: Person under hypnosis cannot be compelled to engage in immoral or dishonest acts.

- Delirium: Individuals in a state of delirium, experiencing hallucinations and delusions, are not held criminally responsible for their actions.

- Drunkenness: According to IPC Section 85, individuals are not criminally liable for acts committed under the influence of alcohol or drugs if they were unaware of their consumption.

- Impulse: Irresistible urges driving individuals to perform specific conscious acts without motive or premeditation, such as kleptomania or pyromania, are not punishable if the impulsive behavior stems from certain organic mental disorders.

Historical Aspects of Concept of Criminal Responsibility

- The concept of criminal responsibility in India, shaped by centuries of British rule, draws heavily from the legal traditions of England and Wales. For a person to be found guilty of a crime, the prosecution must prove all elements of the offense "beyond all reasonable doubt," a stringent standard where the evidence leaves only the slightest possibility of the defendant's innocence. This involves proving both the physical act (actus reus) and the requisite mental state (mens rea, or "guilty mind") for the offense. Mens rea reflects the doctrine that criminal liability hinges on the defendant's intent, often defined in statutes with terms like "intended," "recklessly," "knowingly," or "maliciously." However, certain "strict liability" offenses, typically administrative, do not require proof of mens rea.

- Criminal responsibility assumes individuals are free, intentional beings capable of answering for their actions. This notion underpins most criminal justice systems, where responsibility implies knowledge or control over one’s actions. A person cannot be morally responsible for acts beyond their control. Exceptions are made for those with diminished control, such as children or individuals with mental disorders, whose actions may be excused due to mistake, accident, or provocation.

- The concept of mens rea traces back to the 13th century, as seen in the writings of Henri de Bracton, and was long equated with moral guilt. However, Lady Wootton argued that mens rea is becoming less relevant to responsibility, which she claimed has "withered away." Criminal responsibility remains a legal question for courts to decide, historically defined as liability to punishment. By the 19th century, medical and psychiatric testimony began challenging traditional views, particularly regarding the responsibility of mentally abnormal individuals, though such testimony was not always accepted, as seen in cases like Fooks (1863). The 1953 Royal Commission on Capital Punishment emphasized that responsibility is a moral issue, and criminal law should align with societal moral standards.

- The M'Naghten Rules, a key standard for assessing insanity, raise questions about whether "wrongfulness" refers to legal or moral wrongs. Commentators suggest three interpretations: the illegality standard (exempting those unaware their actions were illegal), the subjective moral standard (exempting those who believed their actions were morally justified due to mental illness), and the objective moral standard (exempting those unable to recognize society’s view of their actions as morally wrong).

- Philosophical debates, from Thomas Aquinas to Lady Wootton, question whether a person’s mental state or responsibility can be truly known, citing the inaccessibility of human consciousness. Cartesian dualism, separating actions from thoughts, and Wootton’s critique of the lack of logical criteria for distinguishing responsibility, further complicate the issue. Despite these philosophical challenges, juries routinely apply common sense to assess intent and responsibility, relying on human insight rather than esoteric moral philosophy. Thus, while philosophers critique the concept, the legal system pragmatically relies on practical judgment to determine criminal responsibility.

The Historical Treatment of the Mentally Abnormal Offender

- In early Indian criminal history, there is limited information available regarding the treatment of the insane.

- Under Roman law, insane offenders were treated with leniency, as madness was considered a form of punishment in itself.

- This perspective was morally acceptable and was influenced by Greek moral philosophy, particularly the ideas of Aristotle, as well as by Hebrew law.

- One of the earliest mentions of the ‘right-wrong test’ can be found in legal texts from this period.

- In the 13th century, Bracton asserted that for a crime to occur, there must be a ‘will to harm,’ implying that individuals with mental health conditions were not criminally responsible.

- Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634) supported this idea in a case called Beverley (1603), arguing that a madman did not understand his actions and therefore lacked criminal intent.

- This laid the groundwork for assessing ‘insanity’ based on whether the individual knew their actions were wrong, known as the ‘right-wrong’ test.

- Sir Matthew Hale, in his History of the Pleas of the Crown (1736), noted that only those who were ‘totally insane’ could use this excuse for criminal responsibility.

- He likened the understanding of a madman to that of a child, suggesting that both lack reason and behave like brute animals.

- Hale’s writings had a significant impact on lawyers in the 18th and 19th centuries.

- Various notable cases during this time helped to clarify the common law stance on the responsibility of individuals deemed ‘mad.’

R v. Arnold (1724)

- In the case of R v. Arnold in 1724, Arnold claimed that Lord Onslow had put a spell on him, leading him to a place filled with devils and imps that disturbed his mind and caused him sleeplessness.

- Arnold believed that Onslow was the source of all the nation's troubles.

- Despite his delusions, Arnold's defense was not successful, possibly because he still exhibited some level of reasoning, and he was eventually hanged.

- During the judge's summary, Arnold was compared to both an infant and a wild beast, which was part of the 'wild-beast test' for assessing criminal responsibility.

- This case established a new standard for criminal responsibility that focused on the ability to distinguish between good and evil.

- This standard later developed into an independent criterion for insanity.

- Following this, juries were allowed to give a special verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity, even if the offender acknowledged their actions but did not comprehend that they were wrong.

R v Earl Ferrers (1760)

- In this case, Earl Ferrers shot Johnson, the receiver of his estate, because he believed Johnson was conspiring against him.

- The shot was not immediately fatal, and Ferrers called for medical assistance.

- During his murder trial, Ferrers claimed he acted on an "irresistible impulse," but this defence was unsuccessful.

- For a prisoner to be acquitted on grounds of lack of reason, there must be a total, permanent, or temporary absence of reason.

R v Hadfield (1800)

- James Hadfield believed he needed to sacrifice his life for the world's salvation.

- He did not intend to commit suicide but thought that by attempting to kill the king, he would be executed.

- On 15th May 1800, Hadfield fired at King George III at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, London.

- Hadfield was tried for treason, a charge that allowed him legal counsel, which was not permitted in other trials until the Prisoner's Counsel Act 1836.

- His lawyer, Erskine, challenged the traditional tests of insanity, arguing that a person could "know what he was about" but still be unable to resist a delusion.

- Hadfield was acquitted largely due to Erskine's strong arguments, and historians believe the jury may have sympathised with Hadfield because of medical evidence of his severe war injuries.

R - v - Bellingham (1812)

- Bellingham, who was paranoid, blamed the Government, particularly Prime Minister Sir Spencer Perceval, for his business problems.

- He assassinated the popular Perceval.

- Despite his mental state, Bellingham was convicted and hanged after the court applied a strict interpretation of the insanity law.

R - v - M’Naghten (1843)

- Daniel M’Naghten, a man with schizophrenia, believed he was being targeted by various authorities, including Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel.

- On January 20, 1843, M’Naghten shot the wrong person, thinking he was targeting Peel.

- The case raised complex questions about the motives behind crimes and the nature of insanity.

- M’Naghten was found not guilty due to his delusion, which impaired his ability to control his actions.

- This decision caused public outrage and led to the establishment of the M’Naghten Rules, defining the legal criteria for insanity.

- The rules state that individuals are presumed sane unless proven otherwise and that the insanity defense requires a significant mental defect affecting the understanding of the act's nature or wrongfulness.

- The test is cognitive and does not account for partial insanity or delusions.

- Critics argue for improvements, such as the 'irresistible impulse' concept, seen in other jurisdictions.

- Various committees have recommended changes to the test in England, but these suggestions were often rejected due to judicial skepticism about partial insanity.

- Baroness Wootton warned that broadening the rules could lead to unclear responsibility.

- After meeting the criteria for insanity, the accused would not be released immediately but kept in custody until further decisions were made.

- This was due to the Criminal Lunatics Act 1800, which ended simple acquittals based on insanity.

- While it seemed to absolve mentally ill offenders of criminal responsibility, it recognised the risks of treating them as innocent.

- Queen Victoria attempted to change the verdict of 'insane' to 'guilty but insane' due to multiple assassination attempts against her.

- Legal cases affirmed that this verdict was indeed an acquittal, but a qualified one.

- The Criminal Procedure (Insanity) Act 1964 reaffirmed the traditional stance on 'special verdicts'.

Diminished Responsibility

- Diminished responsibility is a legal concept that originated in Scottish law before being introduced to England and Wales through the Homicide Act 1957.

- In Scottish law, the idea of partial insanity has been reducing punishments since the 17th Century. However, it was not a separate legal defence but rather a factor that helped lessen the severity of punishment.

- The introduction of diminished responsibility changed the classification of certain crimes from murder to manslaughter.

- According to the Homicide Act 1957:

- If a person kills or is involved in the killing of another and was suffering from an abnormality of mind that significantly impaired their mental responsibility at the time of the act, they should be convicted of manslaughter instead of murder.

- The language used in this legal defence was influenced by the Mental Deficiency Acts of 1913 and 1927. This led to a broad interpretation of what constitutes an abnormality of mind and mental responsibility in legal cases.

- If a defendant successfully proves diminished responsibility, the court can impose a range of penalties, including:

- Life imprisonment

- Commitment to a mental hospital

- Absolute discharge

- The understanding of criminal responsibility has evolved to include not only cognitive factors from common law insanity but also the defendant's ability to control their impulses and demonstrate self-control.

- Despite the intention behind introducing this defence, there was no significant increase in manslaughter convictions compared to murder. Researchers observed that:

- The rates of offenders being found insane at different stages of the legal process remained relatively stable.

- After the introduction of diminished responsibility and the abolition of capital punishment in 1965, offenders were less likely to plead insanity to avoid life imprisonment. Instead, they could plead guilty to manslaughter.

- The introduction of diminished responsibility modernised the legal perspective on insanity and mental illness, aligning it more closely with contemporary understanding and views on these issues.

|

71 docs|3 tests

|

FAQs on Forensic Psychiatry - 2 Chapter Notes - Forensic Medicine and Toxicology (FMT) - NEET PG

| 1. What are the primary symptoms used to diagnose schizophrenia? |  |

| 2. How is criminal responsibility assessed in individuals with mental illness? |  |

| 3. What are the common reasons for psychiatric hospital admission? |  |

| 4. What are the ethical considerations regarding the restraint of mentally ill individuals? |  |

| 5. What responsibilities do individuals deemed insane have in legal contexts? |  |