Textbook Solutions: Melting Ice in Alaska | Gul Mohar Class 8: Book Solutions, Summaries & Worksheets PDF Download

Before You Read

Look at this picture of a polar bear and her cub. Global warming is the greatest threat to our planet and the biggest reason for climate change. Polar bears are in grave danger because of the loss of ice in the Arctic regions due to global warming.

Global warming is the greatest threat to our planet and the biggest reason for climate change. Polar bears are in grave danger because of the loss of ice in the Arctic regions due to global warming. How would you feel if you lost your home? Write one sentence.

Ans: If I lost my home, I would feel extremely scared, helpless, and lonely. A home is not just a shelter, but a place of comfort, love, and family memories. Losing it would mean losing security and a part of my identity.

While Reading

Q1. What do you think is causing the permafrost to thaw?Ans: The permafrost is thawing because of global warming and climate change. Rising global temperatures are heating the ground, melting frozen soil and ice that has been stable for centuries. This process causes land to sink, buildings to tilt, and rivers to overflow, bringing serious damage to the lives of the Yup’ik people.

Q2. Why do you think the word ‘transplant’ has been used here instead of ‘migrant’?

Ans: The word transplant has been used because the Yup’ik people are not moving temporarily like migrants who return. Instead, they are shifting permanently with their families, homes, and traditions. Like a plant uprooted and placed into new soil, they are trying to adjust and grow in unfamiliar surroundings while still carrying their culture and identity with them.

Q3. How can climate change affect the ‘subsistence lifestyle’ of the Yup’ik people?

Ans: Climate change directly threatens the subsistence lifestyle of the Yup’ik people. Melting ice reduces their ability to hunt seals and fish, while floods and erosion destroy land used for food gathering. Rivers become unstable, and the weather makes survival unpredictable. Their close connection with nature becomes disrupted, forcing them to change practices that had sustained their community for centuries.

Q4. Words like gnawing, splashing, rising instead of gnawed, splashed, etc. show that the process is…

Ans: These words show that the process is continuous and still happening. The gnawing of the riverbanks, splashing of waves, and rising waters indicate ongoing destruction. This means the danger is not in the past but continues to threaten the lives of the villagers daily. Such language emphasizes that climate change is not a one-time event but a continuing crisis.

Q5. What do the ‘storms’ refer to?

Ans: The storms refer to violent natural events caused by climate change, including floods, heavy rains, and surging sea waves. These storms constantly erode the land and destroy homes, leaving the Yup’ik people unsafe. With rising sea levels, these storms grow stronger and more frequent, making life in Newtok dangerous. They symbolize the constant threat that forces people to abandon their homeland.

Q6. Martha seems sad that Newtok will become vacant. Why is she sad about it?

Ans: Martha feels sad because Newtok has been her home all her life. Every corner of the village holds her memories, friendships, and the bonds of her community. Leaving it forever means losing not just a place but an identity, a heritage, and a sense of belonging. This emotional connection makes her mourn the loss of her birthplace.

Q7. Read para 15 to 19. Underline the sentences that show ‘mixed emotions’ of the people.

Ans: Sentences such as: “Many folks are not happy to be leaving the place they’ve known their whole lives.” / “They are excited to finally be moving to a place with better services.” / “Some residents are relieved while others feel anxious.” These lines reflect both sadness of leaving and hope for a safer life.

Q8. Martha says ‘our story’. What is she referring to? Why has she used the word ‘story’?

Ans: Martha is referring to the journey of the Yup’ik people who are being forced to leave Newtok. She uses the word story because it is not just her personal experience but a shared history of her community. Calling it a story makes it sound like a chapter in time—one of hardship, loss, and resilience—that future generations will remember.

Understanding the Text

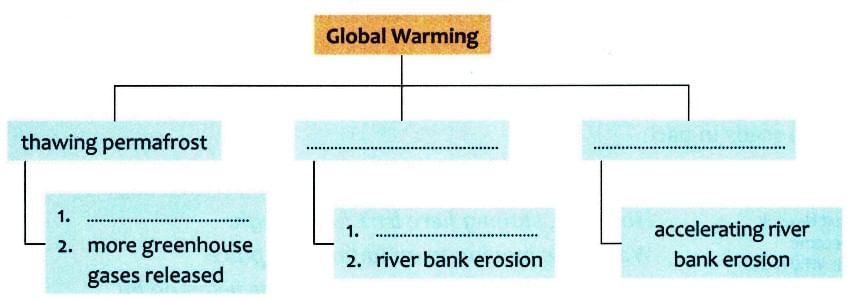

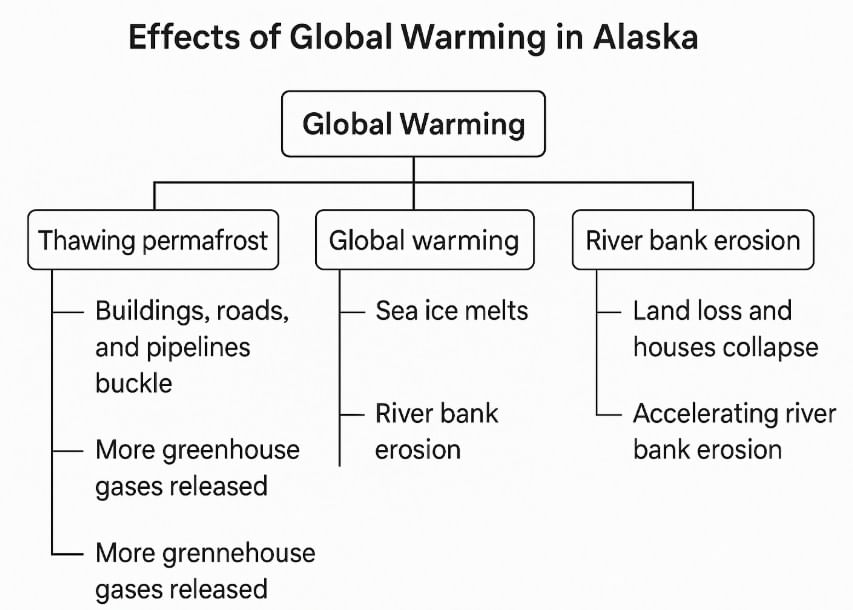

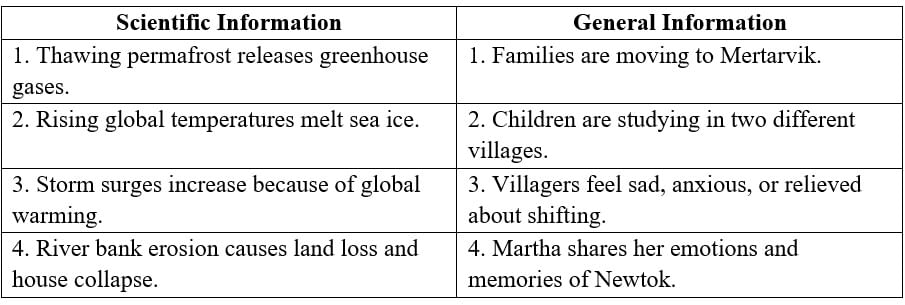

A. Study this chart on the effects of global warming in Alaska and complete it.

Ans:

Ans:

B. Answer these questions.

Q1. What kind of difficulties has thawing permafrost caused to the Yup’ik people?Ans: Thawing permafrost has made ground unstable, so houses tilt, foundations crack, and fuel tanks or boardwalks lean dangerously. Roads and paths sink, clean-water systems fail, and sewage lagoons get breached, creating health risks. Flooding increases as soil loses its frozen structure, forcing costly repairs or demolition. Everyday tasks—fetching water, reaching school, hunting or fishing—become hazardous, while constant anxiety and evacuation alerts strain families and elders.

Q2. How is the Ninglick river a threat to Newtok?

Ans: The Ninglick river aggressively erodes Newtok’s riverbank, especially as sea ice recedes and storms intensify. Each season the channel “eats” the shoreline, moving ever closer to homes, fuel farms, and public buildings. Sudden storm surges can flood the village, contaminate water, and cut evacuation routes. Continued erosion risks isolating sections of the settlement, making services impossible to maintain and ultimately forcing permanent relocation to a safer site.

Q3. Give a reason why the Yup’ik people have waited for two decades to move.

Ans: Relocation required complex, slow steps: securing multi-agency funding, acquiring suitable land, completing environmental studies, and designing climate-resilient infrastructure. Barging materials in brief ice-free windows, building an airstrip, water, power, and housing—all demanded time and money. Community consensus, legal approvals, and prioritizing elders and families stretched timelines. With limited resources and harsh logistics, progress came in phases, explaining why the move has taken nearly two decades.

Q4a. What does ‘higher ground’ mean?

Ans: “Higher ground” refers to land elevated above floodplains, storm-surge zones, and river erosion corridors. Such sites sit well above typical high-water marks, with more stable soils, better drainage, and reduced permafrost melt risk. Building on higher ground lowers exposure to inundation, contamination, and infrastructure failure. In practical terms, it means choosing terrain that remains safe during extreme weather, protecting homes, schools, clinics, and essential services over the long term.

Q4b. Why is the new town being built on ‘higher ground’?

Ans: A site on higher ground lowers flood and erosion hazards, keeping homes from collapsing and utilities from failing. Elevated terrain reduces storm-surge damage, preserves drinking-water safety, and offers firmer soils for foundations, roads, and airstrips. By relocating upslope, the community invests in durable, climate-resilient infrastructure. The goal is not just escape but stability—schools that stay open, clinics that function, and power and sanitation that survive extreme events.

Q4c. What are the challenges that the Yup’ik people face now?

Ans: Families are split between Newtok and the new site, so schooling, healthcare, and caregiving get complicated. Housing is still insufficient; water, power, and sanitation systems are expanding but incomplete. Jobs are limited during transition, while moving costs, supply delays, and brief construction seasons slow progress. Elders miss familiar grounds, adding emotional strain. Balancing cultural continuity with new routines remains difficult as the community rebuilds life step by careful step.

Q5a. What kind of ‘unwanted feelings’ is Martha talking about?

Ans: Martha describes grief at leaving ancestral land, anxiety about uncertain futures, and guilt over departing neighbors or elders who remain. Homesickness mixes with fear of new places, new rules, and changing livelihoods. She also feels sadness for places tied to ceremonies, stories, and graves. These layered emotions—loss, worry, reluctance, and love—arrive together, making departure feel necessary for safety yet painful for memory and identity.

Q5b. Imagine yourself in Martha’s shoes. Why is staying here, in Newtok, no longer fun for her?

Ans: Daily life has turned precarious: boardwalks sag, houses lean, and floods threaten food, fuel, and water. Storms arrive more often, evacuation plans interrupt routines, and subsistence activities become risky. Instead of shared gatherings without worry, every season brings damage and repair. Constant alerts replace ease, and fear for children and elders overshadows small joys. What once felt like home now feels fragile, unsafe, and exhausting to maintain.

Q5c. Why do you think Martha did not go to Mertarvik with her family?

Ans: Strong attachments can slow departures. Martha may be finishing responsibilities—supporting friends, caring for an elder, or completing school or work obligations. Housing availability and seasonal transport also limit immediate moves. She likely wants a proper farewell and time to process leaving. Staying briefly lets her help others pack, safeguard keepsakes, and honor places that shaped her identity before she joins family in Mertarvik.

Q6a. How have the Yup’ik people adapted over time? In what ways have they been ‘flexible’?

Ans: The Yup’ik have repeatedly adjusted lifeways to shifting conditions—moving seasonally for subsistence, then settling in villages when schools and services centralized. They blended traditional knowledge with modern tools, altering hunting, fishing, and travel patterns as ice and rivers changed. Today they’re relocating again, designing safer homes and infrastructure while protecting language, ceremonies, and sharing networks. Flexibility means adapting methods without abandoning cultural values that bind the community.

Q6b. How is the condition of the Yup’ik people a warning for the entire world?

Ans: Newtok’s story foreshadows global displacement from rising seas, thawing ground, and stronger storms. Relocation is costly, slow, and emotionally hard, risking cultural loss and health impacts. Cities, deltas, islands, and river communities everywhere face similar hazards. The lesson is clear: cut emissions, protect ecosystems, and plan equitable adaptation now. Ignoring early warnings turns manageable transitions into emergencies that burden the most vulnerable first—and then everyone.

Appreciating the Text

Q1. This article discusses the conditions of the Yup'ik people of Alaska. What larger message does it have for the reader? What does it make us think about? How, as readers, are we involved in this matter?Ans: The larger message is that climate change is real, urgent, and destructive. It shows us that ordinary people like the Yup’ik community are already losing homes and culture. It makes readers think about our own role in contributing to or preventing such disasters. We are involved by making choices—reducing waste, using energy wisely, and supporting environmental protection. The story warns that ignoring climate change will affect us all.

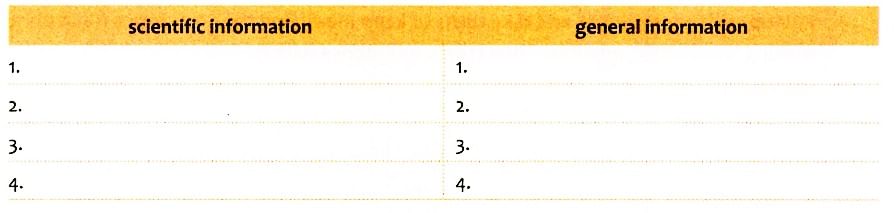

Q2a. Read the text again. Is it a scientific article or a journalistic piece? Fill in the table below with evidence from the text to examine the contents of the text.

Ans:

Q2b. Why has the writer included both scientific and real-life details in the text?

Ans: The writer has included both to make the article informative and relatable. Scientific details explain the reasons for climate change and its consequences, while real-life experiences show its human cost. By combining them, the text appeals to logic and emotion together, helping readers not only understand the problem but also feel empathy. This balance makes the article persuasive and impactful.

|

32 videos|62 docs|17 tests

|

FAQs on Textbook Solutions: Melting Ice in Alaska - Gul Mohar Class 8: Book Solutions, Summaries & Worksheets

| 1. What are the primary causes of ice melting in Alaska? |  |

| 2. How does melting ice in Alaska impact wildlife? |  |

| 3. What are the potential consequences of rising sea levels due to melting ice in Alaska? |  |

| 4. How does melting ice in Alaska contribute to global climate change? |  |

| 5. What measures are being taken to address the effects of ice melting in Alaska? |  |