Class 10 History Chapter 4 Extra Question Answers - The Age of Industrialisation

Short Answer Questions

Q.13. Give one negative impact of the development of cotton textile industry in England on Indian weavers. [2010]

Ans. They could not get enough supply of raw cotton of good quality. The American Civil War stopped the supply of raw cotton to England and the British forced Indian weavers to buy raw cotton at exorbitant prices.

Q.14. Explain the miserable conditions of Indian weavers during the East India Company's regime in the eighteenth century. [2008, 2010]

Ans. Once the East India Company established political power, it started asserting monopoly right to trade. It proceeded to develop a system which gave it control to eliminate all competition, control costs and ensure regular supply of cotton and silk goods. It took the following steps.

First, it eliminated the existing traders and brokers and established direct control over the weaver. It appointed a special officer called the 'gomastha' to supervise weavers, collect supplies and examine the quality of the clothes.

Second, it prevented the Company weavers from dealing with other buyers. They advanced loans to weavers to purchase the raw materials, after placing an order. The ones who took loans had to give their cloth to the gomashta. They could not sell it to any other trader.

Weavers took advance, hoping to earn more. Some weavers even leased out their land to devote all time to weaving. The entire family became engaged in weaving. But soon there were fights between the weavers and the gomashtas. The latter used to march into villages with sepoys and often beat up the weavers for delays in supply.

In many places like Carnatic and Bengal, weavers deserted the villages and had to migrate to other villages. In many places they revolted against the Company and its officials. Weavers began refusing to accept loans after some time, closed down their workshops and became agricultural labour.

Q.15. Write a short note on the role of advertisement during the British rule. [2008, 2010]

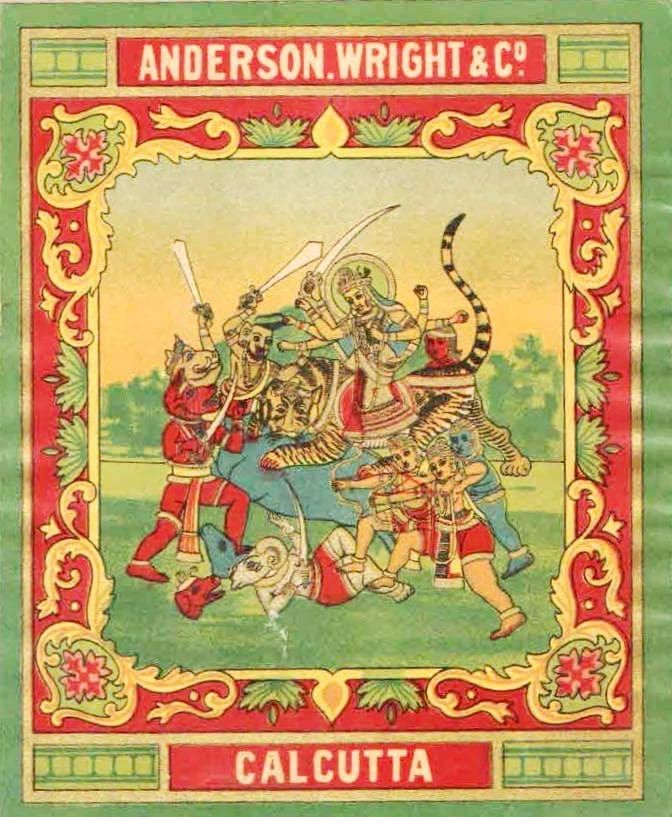

Ans. Manchester industrialists used their labels on clothes sold in India with bold letters, “Made in Manchester” to inspire confidence amongst the buyers. Images were sometimes used instead of labels. Common images of the time were images of Gods and Goddesses, probably to give the product a divine approval. Sometimes, figures of emperors and nawabs also adorned calendars, which were an effective advertising tool as they could be hung and used by everyone and everywhere.

Example of an advertisement during British Rule

Example of an advertisement during British Rule

Q.16. How did the British manufacturers attempt to take over the Indian market with the help of advertisements? Explain with three examples. [2008, 2010]

OR

Explain four ways that helped the British to take over the Indian market with the help of advertisements.

Ans.

(i) When Manchester industrialists began selling cloth in India, they put labels on the cloth bundles. The label served two purposes. One was to make the place of manufacture and the name of the company familiar to the people. The second was that the label was also a mark of quality. When the buyers saw “Made in Manchester” written in bold on the label, they felt confident about buying the cloth.

(ii) Besides words and texts, they also carried images. Beautifully illustrated images of Indian Gods and Goddesses appeared on these labels. For example, images of Kartika, Laxmi, Saraswati were shown on imported cloth label.

(iii) Historic figures like those of Maharaja Ranjit Singh were used to create respect for the product. The image, the labels, the historic figures were intended to make the manufacture from a foreign land appear somewhat familiar to Indian people.

(iv) Manufacturers printed calendars to popularise their products calendars could be used ever by people who could not read. Advertisement could be seen day after day, throughout the year, when hung on the walls.

Q.17. Explain with examples how an average worker in mid-nineteenth century was not a machine operator but a traditional craftsperson and labour. [2008, 2010]

Ans. The most dynamic industries in Britain were cotton and metals. But these industries did not displace traditional industries. Even at the end of 19th century only 20% of the total workforce was employed in technologically advanced industries. Ordinary and small innovations were the basis of growth in many non-machanised sectors such as food processing, buildings, pottery, glasswork, tanning etc. Again, technological changes occurred slowly. New machines were expensive and broke down often. Repair was costly. Take the case of steam engine. James Watt improved the steam engine produced by new comer in 1781. But for years there were no buyers. There were only 321 steam engines in England at the beginning of the 19th century. Of these 50 were in cotton industry, nine in wool and rest in mining. Steam engines were used much later so a typical worker in the mid-19th century was not a machine operator but a traditional craftsperson.

Q.18. Explain any three problems faced by the Indian weavers by the turn of the 19th century. [2009, 2010, 2011 (T-1)]

Ans. The three problems faced by weavers by the turn of the 19th century were :

(i) Decline in export market : By 1860s insufficient supply of raw cotton of good quality affected the Indian weavers. Due to the American civil war, the supply of raw cotton from USA had stopped. Britain turned to India for new cotton export. This resulted in price rise and the Indian weavers suffered. In the beginning of the 19th century, there was a sharp decline in Indian export of cotton piece exports. In 1811-12, 33% of exports were made in price goods. In 1850-51, it was no more than 3%.

(ii) The British started dumping mill-made and machine-made British goods in India. British exports to India for textile goods increased from 31% to over 50% in the 1870s. The local markets collapsed as they were glutted with Manchester imports. Machine-made goods were sold at lower prices and Indian weavers could not compete with them.

(iii) Another problem cropped up for weavers. At the end of the 19th century, India started producing cotton textiles in factories and punished and the weavers for delays in supply, often beating and flogging them. The weavers lost the power to bargain for prices and sell to different buyers. The Company paid them a miserably low price. The loans tied them to the Company. It led to deserted villages and migration to other cities.

Q.19. Explain the impact of First World War on Indian industries. [2010]

OR

Why did industrial production in India increase during the First World War?

Ans. Till the First World War, industrial growth in India was slow. The war created a dramatically new situation. Manchester imports into India declined due to the war. The British factories became busy with producing things needed for the army. Indian mills now suddenly had a large market to supply. The long war made the Indian factories supply them with jute bags, cloth for army uniforms, tents and leather boots, horse and mule saddles, and a host of other items. Many workers were employed for longer hours. After the war Manchester goods lost their hold on the Indian markets. British economy collapsed as it could not compete with the USA, Japan, and its European rivals. The Indian industrialists captured the local market. Small scale industries prospered.

Q.20. Explain any three major problems faced by new European merchants in setting up their industries in towns before the Industrial Revolution. [2010]

Ans. New European merchants faced problems in setting up their industries in towns for three major reasons :

(i) The urban crafts and trade guilds were powerful. These were associations of producers that trained craftspeople and maintained control over production.

(ii) They regulated competition and prices and restricted the entry of new people into the trade.

(iii) Rulers granted different guilds monopoly right to produce and trade in specific products.

Q.21. How had a series of inventions in the eighteenth century increased the efficiency of each step of the production process in cotton textile industry? Explain. [2010]

Ans. A series of inventions in the 18th century increased the efficiency of each step of the production process in cotton textile industry.

(i) Each step means carding, twisting, spinning and rolling. They enhanced the output per worker, enabling each worker to produce more and produce stronger threads and yarn.

(ii) Richard Arkwright created the cotton mill. Before this, cloth production was carried out within village households. Now costly machines could be set up in the mill and all the mill of Industrialisation processes were completed under one roof.

(iii) Spinning jenny devised by James Hargreaves in 1764 speeded up the spinning process and reduced labour demand. By turning one single wheel, a worker could set in motion a number of spindles and spin several threads at a time.

(iv) The steam engine, invented by James Watt in 1781, was used in cotton mills.

(v) Factories came up in large numbers and by 1840, cotton textile became the leading sector in industrialisation. The expansion of railways also helped in production of textile goods.

Q.22. What is meant by proto-industrialisation? Why was it successful in the countryside in England in the 17th century? [2010, 2011 (T-1)]

Ans. Proto-industrialisation refers to first or early form of industrialisation. Even before the factories came up in England and Europe, there was large-scale industrial production for an international market, not based on factories. This phase of industrialisation is referred to as proto-industrialisation.

Guilds were associations of producers that trained crafts people, maintained control over production, regulated competition and prices and restricted the entry of new people into the trade.

Q.23. ‘Technological changes occurred slowly in Britain.’ Give three reasons for this. [2010, 2011 (T-1)]

Ans. Technological changes occurred slowly because :

(i) New technology was expensive and merchants and industrialists were cautious about using it.

(ii) They did not spread dramatically a cross the industrial landscape.

(iii) The machines often broke down and repair was costly.

(iv) They were not as effective as their inventors and manufacturers claimed.

For example : For years there were no buyers for the steam engine improved by James Watt and they were not used in the industry till much later in the 18th century. So even the most powerful technology had enhanced productivity of labour manifold was slow to be accepted by industrialists.

Q.24. What led to expansion in handloom craft production between 1900 and 1940? [2010 (T-1)]

Ans. In the 20th century, handloom craft actually expanded, handloom cloth production expanded steadily almost trebling between 1900 and 1940.

(i) This was partly due to technological changes. Handicrafts people adopted new technology which improved production without pushing up the costs excessively. Weavers started using a fly shuttle which speeded up production and reduced labour demand. By 1941, over 35% of handlooms in India were fitted with fly shuttles. In Travancore, Madras, Mysore, Cochin and Bengal the proportion was 70 to 80%. There were several other innovations that helped weavers.

(ii) The demand for finer Varieties bought by the well-to-do was always stable, unlike the coarse variety. Famines did not affect the sale of Banarasi or Baluchari saris. Mills could not produce saris with woven borders, or the famous lungis and handkerchiefs of Madras. Handlooms cloth production in the 20th century almost trebled between 1900-1940.

Q.25. Vasant Parkar, who was once a mill worker in Bombay, said : [2010 (T-1)]

‘The workers would pay the jobbers money to get their sons work in mill .... The mill worker was closely associated with his village, physically and emotionally. He would go home to cut the harvest and for sowing. The Konkani would go home to cut the paddy and Gahti, the sugarcane. It was accepted practice for which the mills granted leave.’

(i) Why do workers pay a jobber?

(ii) In what ways did the mill workers remain associated with the village?

(iii) Why did mill workers go to the village?

Ans.

(i) Workers paid a jobber because he got jobs for them, helped them to settle in the city and provided them money in times of crisis. For these favours he was paid.

(ii) The workers in the mill came from the villages or neighbouring districts. For example, 50% workers in the Bombay cotton industries in 1911 came from neighbouring districts of Ratnagiri, from mills of Kanpur, from surrounding districts of Kanpur.

(iii) Most often mill workers moved between the villages and the city, returning to their village homes during harvests and festivals.

Q.26. Explain any three functions of a jobber. [2010, 2011 (T-1)]

Ans. The three functions of a jobber were :

1. To recruit new people from his village and ensure them jobs.

2. To help them to settle in the cities.

3. To provide money to the workers in time of crisis.

Q.27. Who were the Gomasthas? Why did the weavers and Gomasthas clash? [2010, 2011 (T-1)]

Ans. Gomasthas were paid servants of the East India Company. Their job was to supervise weavers, collect supplies, and examine the quality of cloth. The weavers clashed with the Gomasthas because they were outsiders with no long-term link with the villages. They acted arrogantly marched into villages with sepoys and peons and punished weavers for delays. They often beat and flogged the workers.

Q.28. Mention the name of three Indian entrepreneurs and their individual contribution during the nineteenth century. [2010 (T-1)]

Ans. The three Indian industrialists of the 19th century were :

(i) Dwarkanath Tagore,

(ii) Dinshaw Petit & Nusserwanjee Tata

(iii) Seth Hukum Chand

Dwarkanath Tagore set up six joint stock companies in the 1830s and 1840s. In Bombay, Dinshaw Petit and Nusserwanjee Tata built huge industrial empires in India. Seth Hukumchand, a Marwari businessman set up the first jute mill in Calcutta in 1917.

Q.29. Why were Victorian industrialists not interested to introduce machines in England? Give any four reasons. [2010 (T-1)]

OR

Why were some industrialists in the 19th century Europe prefer hand labour over machines. 2011 (T-1)]

Ans. The four reasons are :

(i) There was no shortage of human labour in the Victorian England. When there is plenty of labour, wages are low, the industrialists did not want to introduce machines that got rid of human labour, and required large capital investment.

(ii) In many industries demand for labour was seasonal (for example, gas works and breweries) So more workers were needed in peak season. So, industrialists usually preferred hand labour, employing workers for the season only.

(iii) A range of products could be produced only by hand labour. Machines could produce standardised goods for a mass market. The demand in the market was for goods with intricate designs and specific shapes (for example - hammers). These required human skills, not mechanical technology.

(iv) In Victorian Britain, the upper classes the aristocrats and the bourgeoisie preferred things produced by hand. Handmade products symbolised class and refinement. They were better finished and carefully designed. Machine made goods were for exports to colonies only.

Q.30. What role did the Indian merchants play in the growth of textiles industries before 1750? Explain any three points. [2010 (T-1)]

Ans. Before 1750, Indian merchants were involved in a network of export trade. Silk and cotton goods from India dominated the international market in textiles. Surat and Gujarat Coast connected India to Gulf and Red Sea ports. Masaulipatam on the Coromondal Coast and Hooghly in Bengal had trade links with Southeast Asian ports. Indian merchants managed financial production, carrying goods and supplying exporters. They gave advances to weavers, procured the woven cloth from weaving villages and carried supplies to the ports. At the port, the big shippers and export merchants had brokers who negotiated the price and bought good from the supply merchants operating inland.

Q.31. After industrial development in England, what steps did the British government take to prevent competition with the Indian textiles? [2010 (T-1)]

Ans. The British Government prevented competition with Indian textiles by :

- They imposed import duties on textile goods so that Manchester goods could sell in Britain without facing any competition from outside.

- The industrialists persuaded East India Company to sell British goods in Indian markets, and export of British cotton goods increased.

- At the end of 18th century there was virtually no import of cotton goods from India. The value of cotton goods constituted 31% in 1850 but by 1870s the figure was over 50%.

Q.32. How did a series of changes affect the pattern of industrialisation by the first decade of the 20th century? Explain any three. [2010 (T-1)]

Ans. When the Swadeshi Movement, the nationalists mobilised people to boycott foreign cloth

(i) Industrial groups organised themselves to protect their collective interests. They pressurised the government to increase tariff protection and grant other concessions

(ii) From 1906, export of Indian yarn to China declined, so industrialists in India began shifting from yarn to cloth production.

(iii) Cotton piece goods production doubled in India between 1900 and 1912.

Q.33. Mention any three restrictions imposed by the British government upon the Indian merchants in the 19th century? [2010, 2011 (T-1)]

Ans. The British Government in the 19th century tightened their control over Indian merchants.

(i) They were barred from trading with Europe in manufactured goods.

(ii) They had to export mostly raw materials and food grains — raw cotton, opium, wheat and indigo — required by the British. They were also edged out of the shipping industries.

(iii) European Managing Agencies, in fact, controlled a large sector of Indian business : three of the biggest ones were, Bird Heighlers Co, Andrew Yule, and Jardine Skinnr & Co. In most cases Indian financiers provided the capital while the European Agencies made all investment and business decision. Indian businessmen were not allowed to join European merchant, industrialists.

Q.34. Why did Indian industrialists begin to shift from yarn to cloth production? Give three reasons. [2010 (T-1)]

Ans. Indian industrialists began to shift from yarn to cloth production for the following reasons:

(i) The Swadeshi Movement mobilised people to boycott foreign cloth. This encouraged Indian industrialists to produce cloth, as Indian mills had a vast home market to supply, and Manchester imports into India declined.

(ii) Export of Indian yarn to China declined from 1906 as produce from Chinese and Japanese mills flooded the Chinese market. So Indian industrialists to began to shift from yarn to cloth production.

(iii) After the First World War, Manchester could not capture its position in Indian markets. This enabled the local industrialists in the colonies to capture the home market, and consolidate their position.

Q.35. Why did the East India Company appoint Gomasthas in India? [2011 (T-1)]

Ans. The company tried to eliminate the existing traders and brokers connected with the cloth trade, and establish a more direct control over the weaver. It appointed a paid servant called the gomastha to supervise weavers, collect supplies, and examine the quality of cloth.

Q.36. Why there was no shortage of human labour in Victorian Britain in the mid of nineteenth century? [2011 (T-1)]

Ans. Poor peasants and vagrants moved to the cities in large numbers in search of jobs, waiting for work. Industrialists did not want to introduce machines that got rid of human labour and required large capital investment. A range of products could be produced only with hand labour. For instance, in mid-nineteenth century Britain, 500 varieties of hammers were produced and 45 kinds of axes. These required human skill. Moreover, in Victorian Britain, the upper classes preferred things produced by hand.

Q.37. Why did women workers in Britain attack the Spinning Jenny? Give any three reasons.[2011 (T-1)]

Ans.

(i) Spinning Jenny speeded up the spinning process and reduced labour demand.

(ii) The fear of unemployment made workers hostile to the introduction of new technology.

(iii) When the Spinning Jenny was introduced in the woolen industry, women who survived on hand spinning lost their job and began attacking the new machines.

Q.38. Why do historians agree that the typical worker in the mid-nineteenth century was not a machine operator but the traditional craftsperson and labourer? Explain. [2011 (T-1)]

Ans.

(i) The industrialists were very hesitant to introduce new machines for a variety of reasons.

(ii) Due to abundance of human labour, industrialists had no problem of labour shortage or high wage costs. Machines required large capital investment.

(iii) Goods with intricate designs and specific shapes (like hammer, axes, etc.) required human skill, not mechanical technology.

(iv) The upper classes preferred things produced by hand.

Long Answer Questions

Q.12. Explain the main features of proto-industrialisation. [2010]

OR

Throw light on production during the proto-industrialisation phase in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries with an example [2011 (T-1)]

OR

Enumerate the features of proto-industrialisation. [2011 (T-1)]

OR

How did the poor peasants and artisans benefit during the proto-industrialisation phase? [2011 (T-1)]

Ans. Proto-industrialisation refers to a phase of industrialisation which was not based on factories. Even before factories began to appear, there was large-scale industrial production for international market.

(i) In the 17th and 18th centuries merchants in Europe began to move to the countryside. They gave money to peasants and artisans to produce for an international market. The demands of goods had increased due to colonisation and the resultant expansion of trade. Merchants could not increase production in towns due to the monopoly and power of the crafts and trade guilds. They had the monopoly to produce certain goods and did not allow the entry of new competitors. The guilds were associations of producers that trained craftspeople, maintained control over production, and regulated prices.

(ii) The peasants and farmers started working for the merchants. At this time open fields were disappearing and the poor farmers were looking to new avenues of livelihood. Merchants offered advances to produce goods to them which the peasants eagerly accepted. They could stay in the countryside and continue to cultivate their small lands. Proto-industralisation added to their shrinking income.

(iii) The proto-industrial system became a network of commercial exchanges. A merchant clothier purchased wool from a wool stapler, carried it to the spinners, weavers took up the later stages of weaving, and later fullers and dyers stepped in. The finishing of the cloth was done in London before the export merchant sold it to the international market. At every stage of production 20 to 25 workers were employed by each merchant, with each clothier thus controlling hundreds of workers.

Q.13. Describe the peculiarities of Indian industrial growth during the First World War. [2010]

Ans. l Before the First World War industrial growth was slow.

- War created a different situation.

- British occupation with the war, Manchester imports into India declined.

- Indian mills had a vast market to supply.

- Indian factories supplied jute bags, cloth for army uniforms, tents and leather boots, and host of other items.

- New factories were set up and old ones started working multiple shifts.

- Many new workers employed, worked for longer hours.

- Boom in industrial production; India also produced war goods.

- Britain failed to recapture its former economic power.

- Within the colonies, that is the Indian industrialists consolidated their position, captured the home market and took the place of foreign manufacturers.

Q.14. How did the Industrial Revolution in England affect India’s economy? [2010, 2011 (T-1)]

Ans.

(i) Industrial Revolution in England led to the beginning of long decline of textile exports from India. In 1811-12 cotton goods accounted for 33% of India’s exports; by 1850-51 it was no more than 3 per cent.

(ii) As industries developed in England, industrial groups forced the government to impose import duties on textile goods, so that British goods could sell in Britain without competition. They forced the Company to sell their goods in India, so as a result, by 1850 import of goods to India increased to 50% as compared to 31% earlier.

(iii) Indian markets were glutted with machine-made Manchester goods which were cheaper and Indian weavers could not compete with them. Indian markets suffered from paucity, of raw material, for which they had to pay a higher price, as Indian raw materials were bought by the British at a cheaper price.

Q.15. Give reasons why the handloom weavers in India survived the onslaught of the machine made textiles of Manchester? [2010 (T-1)]

Ans. Handloom weavers in India survived the onslaught of machine-made textiles of Manchester because of :

(i) The technological changes. They adopted new technologies which improved production without putting up the costs.

(ii) The use of a fly shuttle with a loom increased productivity per worker speeded up production and reduced labour demand. By 1941, over 35% of handlooms in India were fitted with fly shuttles. In some regions like Travancore, Madras, Mysore, Cochin and Bengal the proportion was 70 to 80 per cent. There were several other innovations that helped weavers improve their production.

(iii) Another reason was that the demand for finer varieties of yarn, bought by the well-to-do was stable. The coarser cloth, bought by poor, suffered in comparison when there were famines or bad harvests. The rich could buy Banarasi or Baluchari sarees even when there were famines. Mills could not produce sarees with woven borders or famous lungis of Madras, so the weavers survived. They could not be easily displaced by mill production.

Q.16. Discuss four factors responsible for the decline of the cotton textile industry in India in the mid-nineteenth century. [2010 (T-1)]

Ans. The four factors responsible for the decline of cotton textile industry in India were :

(i) European managing agencies which dominated industrial production in India, were interested in certain kinds of products. They established tea and coffee plantations, invested in mining, indigo and jute. These products were required for export trade and not for sale in India.

(ii) Indian businessmen set up industries in the late 19th century which avoided competition with the Manchester goods. The Manchester goods were cheaper and mill-made.

(iii) The British disallowed Indian merchants to trade with Europe in manufactured goods. They had to export raw materials and food grains — raw cotton, opium, wheat and indigo.

(iv) The British monopolised and controlled a large sector of Indian industries. Their agencies mobilised capital, set up joint stock companies and managed them. They made all the decisions in their favour though the Indian businessmen provided the finance.

Q.17. Explain why industrial production in India increased during the First World War. [2010, 2011 (T-1)]

OR

How did industrial production in India increase during the First World War.

OR

“The First World War created favourable conditions for development of industries in India.” Give examples. [2011 (T-1)]

Ans. Industrial production in India increased during the First World War

(i) British mills became busy with war production and Manchester imports into India declined.

(ii) Suddenly Indian factories had a vast home market to supply goods.

(iii) Indian factories were called upon to supply war needs : jute bags, cloth for army uniforms, tents and leather boots, horse and mule saddles and a host of other items.

(iv) New factories were set up and old ones ran multiple stufts. Many new workers were employed and everyone was made to work longer hours. Over the war years industrial production boomed.

(v) After the war, Manchester could not recapture its old position in the Indian market. The economy of Britain collapsed after the war, cotton production and exports fell. Local industrialists in India consolidated their position, substituting foreign goods and capturing the home market.

Q.18. “The modern industrialisation could not marginalise the traditional industries in England.” Justify the statement with any four suitable arguments. [2010, 2011 (T-1)]

Ans.

(i) The new industries could not easily displace traditional industries. At the end of 19th century itself, less than 20% of total workforce was employed in advanced technological industrial centres. Textile industry itself produced a large portion of its output not within the factories, but outside, within domestic units.

(ii) In non-mechanised sectors such as food processing, building, pottery, glass work, tanning furniture making and production of implements, ordinary and small innovations were the basis of their grants.

(iii) Technological changes were not accepted at once by the industrialists. Their growth was slow as new technology was expensive and often broke down; and repairs are costly.

(iv) The traditional craftsmen and labour and not a machine operator was still more popular. Hand-made things were popular, as machines produced mass designs and there was no variety. For example, human skill produced 45 kinds of axes and 500 varieties of hammers, which no machine could produce.

Q.19. What measures were adopted by the producers in India to expand the market for their goods in the nineteenth century? [2010 (T-1)]

Ans.

- When Indian businessmen set up industries in the late 19th century they avoided competing with Manchester goods in the Indian market.

- Since yarn was not an important part of British imports into India, the early cotton mills of India produced coarse cotton yarn (thread) rather than fabric.

- Imported yarn was of the finest quality.

- The yarn produced in Indian spinning mills was used by handloom weavers or exported to China.

- Dwarkanath Tagore set up six joint stock companies in 1830s and 1840s. In Bombay Parsis like Dinshaw Petit and Nusserwanjee Tata accumulated their wealth through exports to China. Some merchants traded with Burma while others had links with Middle East and East Africa. Some operated in India itself and when opportunities of investment in industries opened up, set up factories.

Q.20. Describe any four impacts of Manchester imports on the cotton weavers of India. [2011 (T-1)]

Ans.

(i) Cotton weavers faced two problems. Their export market collapsed, and the local market shrank being glutted with Manchester imports. The imported machine-made goods were cheaper and of better quality.

(ii) Due to American civil war Britain turned to India for cotton. As raw cotton exports increased prices of raw cotton shot up. Indian weavers were starved of supplies and forced to buy at exorbitant prices.

(iii) By the end of 19th century, factories in India began production, flooding the market with machine-goods.

Q.21. What were the principal features of industrialisation process of Europe in 19th century? [2011 (T-1)]

Ans.

(i) The most dynamic industries in Britain were cotton and metals. Cotton was the leading sector in the first phase of industrialisation. Soon iron and steel led the way.

(ii) The new industries could not easily displace traditional industries. A large portion of textile output was produced not within factories but within domestic units.

(iii) The pace of change in ‘traditional’ industries was not set by stream-powered cotton or metal industries but by ordinary and small innovations.

(iv) The technological changes occurred slowly. They didn’t spread dramatically across the industrial landscape.

Q.22. Explain how the condition of the workers steadily declined in the early twentieth century Europe. [2011 (T-1)]

Ans. The abundance of labour in the market affected the lives of workers. Thousands tramped to cities for work. Many job-seekers had to wait weeks, spending nights in open sky or under bridges or in night shelters. Seasonality of work in many industries meant prolonged periods without work. After the busy season was over, the poor were in the streets again hardly eating enough.

The workers’ wages increased but so did the prices enabling lesser purchase of goods. Most of the workers were irregularly and seasonally employed pushing them to the brink of starvation and disease.

Q.23. Why in Victorian Britain, the upper classes preferred things produced by hand? Give four reasons. [2011 (T-1)]

Ans.

(i) Handmade products came to symbolise refinement and class.

(ii) They were better finished, individually produced, and carefully designed.

(iii) Machine-made goods were for masses, for colonies, not for classes.

(iv) Handmade goods were costlier, of better quality and fine threads.

|

66 videos|800 docs|79 tests

|

FAQs on Class 10 History Chapter 4 Extra Question Answers - The Age of Industrialisation

| 1. What was the Industrial Revolution? |  |

| 2. How did the Industrial Revolution impact society? |  |

| 3. What were some of the key inventions during the Industrial Revolution? |  |

| 4. Why did the Industrial Revolution begin in Britain? |  |

| 5. What were the consequences of the Industrial Revolution? |  |