Class 7 History Notes - Towns, Traders And Craftspersons

Introduction

When a traveller visited a medieval town, what they found would vary based on the type of town it was. Towns in medieval times served different purposes, like being a place of worship (temple town), a hub for governing activities (administrative centre), a marketplace for trade (commercial town), or a port for maritime activities. Often, towns had multiple roles, serving as both administrative centres and places for temples, trade, and craft production.

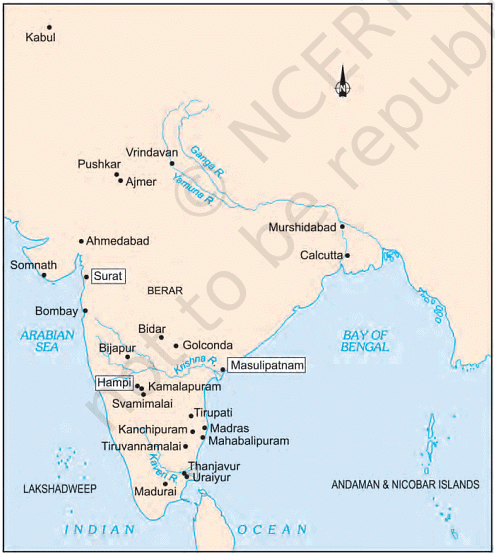

Some important centres of trade and artisanal production in central and south India.

Some important centres of trade and artisanal production in central and south India. Administrative Centres

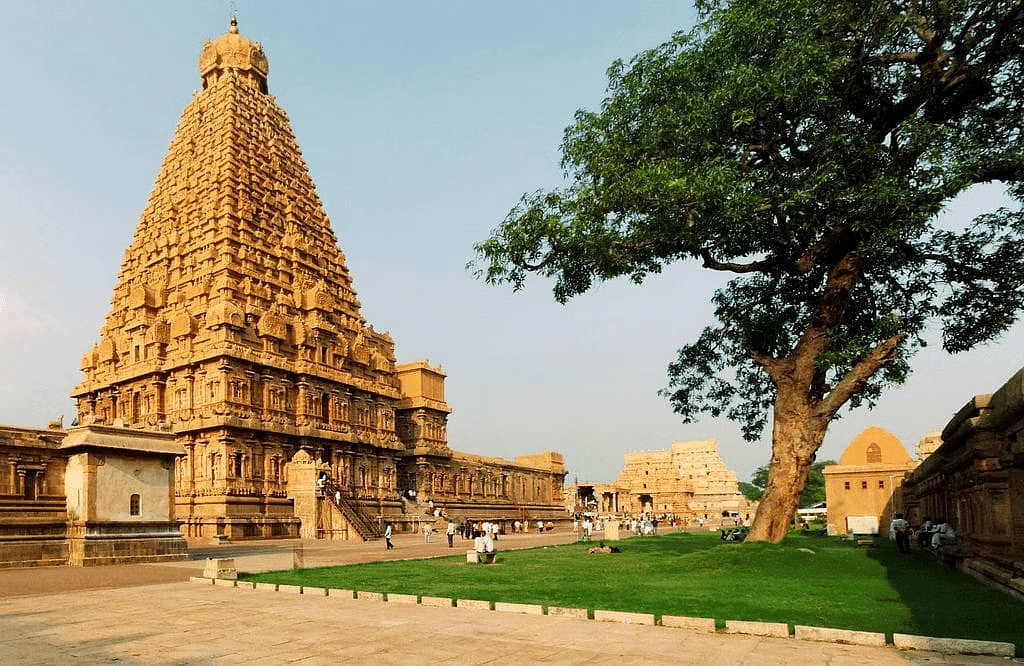

Thousand of years ago, Thanjavur, the Chola capital was a beautiful town near the Kaveri river, featuring the Rajarajeshvara temple built by King Rajaraja Chola.

Rajarajeshvara temple

Rajarajeshvara temple

- The architect, Kunjaramallan Rajaraja Perunthachchan carved his name on the temple wall, which houses a massive Shiva linga.

- The town boasts palaces with mandapas for royal court sessions and army barracks. Busy markets offer grain, spices, cloth, and jewelry. Water came from wells and tanks.

- Saliya weavers in Thanjavur and Uraiyur produce cloth for temple flags, fine cotton for the elite, and coarse cotton for the masses. Skilled sculptors in Svamimalai craft bronze idols and ornamental bell metal lamps. The town is alive with craftsmanship, trade, and cultural richness.

Temple Towns and Pilgrimage Centres

Temples played a central role in the economy and society, with rulers constructing them to showcase their devotion to various deities. They generously supported temples with grants of land and money for rituals, feeding pilgrims and priests, and organizing festivals. Pilgrims visiting the temples also made donations.

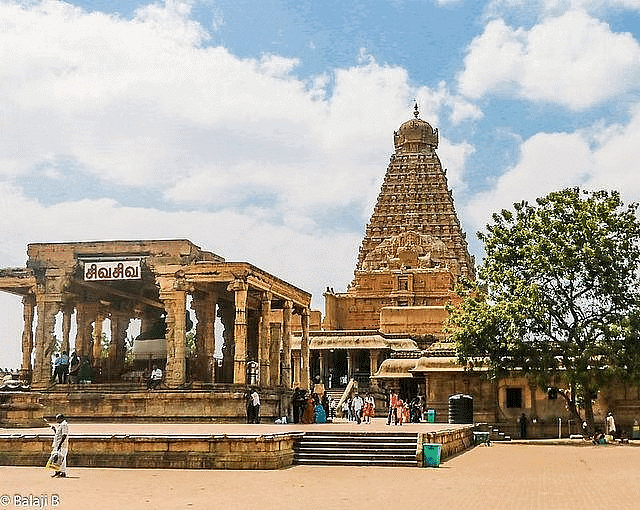

Thanjavur's Temple Town: Thanjavur is an example of a temple town, showing how cities grow around important religious places.

A temple of Thanjavur

A temple of ThanjavurRole of Temples:

- Temples were super important in the local area.

- Rulers built temples to show how much they loved different gods.

- They gave lots of land and money to temples for prayers, helping pilgrims, and big parties.

Economic Impact:

- People giving money and rulers' gifts made temples super-rich.

- Temple leaders also did trade and banking, making a big impact on the local money stuff.

Growth of Temple Towns:

- Temples became so cool that towns started around them.

- These towns had priests, workers, artists, and traders helping the temple and pilgrims.

- Examples are Bhillasvamin, Somnath, Kanchipuram, Madurai, and Tirupati.

Transformation of Pilgrimage Centers:

- Places where people went for religious trips became towns.

- Cool examples are Vrindavan and Tiruvannamalai.

Religious Coexistence:

- Ajmer was once a king's capital and later a Mughal place.

- People from different religions lived together.

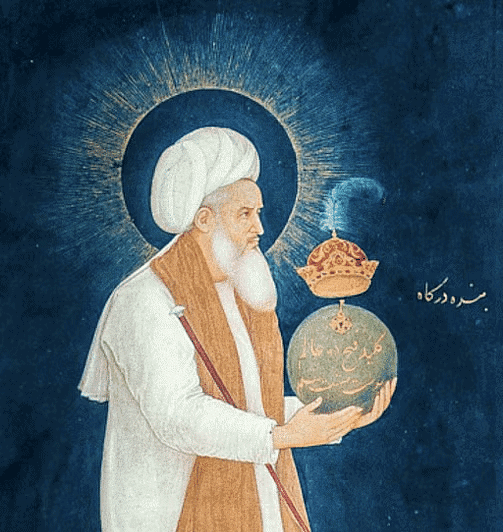

Khwaja Muinuddin Chishti

Khwaja Muinuddin Chishti - A special person named Khwaja Muinuddin Chishti settled there and got fans from all beliefs.

- There's also a lake called Pushkar nearby that's been a holy place forever.

A Network of Small Towns

Starting from the 8th century, small towns began to emerge across the subcontinent. These likely originated from larger villages and featured a central marketplace known as mandapika (later called mandi), where local villagers brought their goods for sale.

These towns also boasted market streets, called hatta (later haat), hosting various shops catering to different trades like pottery, oil pressing, sugar making, and more.

Traders played a pivotal role, with some settling in the towns and others moving between them. Many traders traveled from distant places to these towns, bringing local products and selling items sourced from far-off regions, such as horses, salt, camphor, saffron, betel nut, and spices like pepper.

Typically, a local ruler, known as a samanta or later a zamindar, erected a fortified palace either in the town or nearby. They imposed taxes on traders, artisans, and trade commodities. At times, they delegated the "right" to collect these taxes to local temples, which were either constructed by them or affluent merchants. These rights were documented in inscriptions that have endured through time.

Traders Big and Small

There were various types of traders, including those dealing with horses called Banjaras. They formed groups, and their leaders talked with warriors interested in buying horses.

Banjaras

Banjaras

Caravans and Guilds: Traders traveled in groups called caravans to protect themselves while passing through different areas. They also formed guilds, like the Manigramam and Nanadesi, for trading within India and with countries like Southeast Asia and China.

Trading Communities: Some groups, such as the Chettiars and Marwari Oswal, became the main trading communities. Gujarati traders, including Hindu Baniyas and Muslim Bohras, played a big role in trade with regions like the Red Sea, Persian Gulf, East Africa, Southeast Asia, and China.

Marwani business communityThey traded textiles and spices, getting items like gold, ivory, spices, tin, Chinese blue pottery, and silver.

Marwani business communityThey traded textiles and spices, getting items like gold, ivory, spices, tin, Chinese blue pottery, and silver.The west coast towns had traders from different places, like Arab, Persian, Chinese, Jewish, and Syrian Christian traders.

Indian goods like spices and cloth sold in places like the Red Sea, and Italian traders brought them to European markets. These items became popular in Europe, leading to more European traders coming to India.

The demand for Indian goods in European markets brought European traders to India. Indian spices and cloth became important in European cooking and fashion, changing how Europeans traded and used goods.

Crafts in Towns

The craftspersons in Bidar were renowned for their inlay work, known as Bidri, using copper and silver. Bidri/Inlay on Metal The Panchalas or Vishwakarma community, consisting of various skilled workers like goldsmiths, bronzesmiths, blacksmiths, masons, and carpenters, played a vital role in constructing temples, palaces, large buildings, and water structures.

Bidri/Inlay on Metal The Panchalas or Vishwakarma community, consisting of various skilled workers like goldsmiths, bronzesmiths, blacksmiths, masons, and carpenters, played a vital role in constructing temples, palaces, large buildings, and water structures.

Weavers like the Saliyar or Kaikkolars became prosperous communities and contributed to temples. Specific tasks in cloth making, such as cleaning, spinning, and dyeing cotton, became specialized and independent crafts.

A Closer Look: Hampi, Masulipatnam and Surat

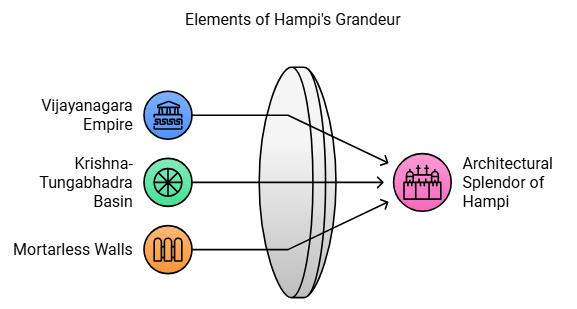

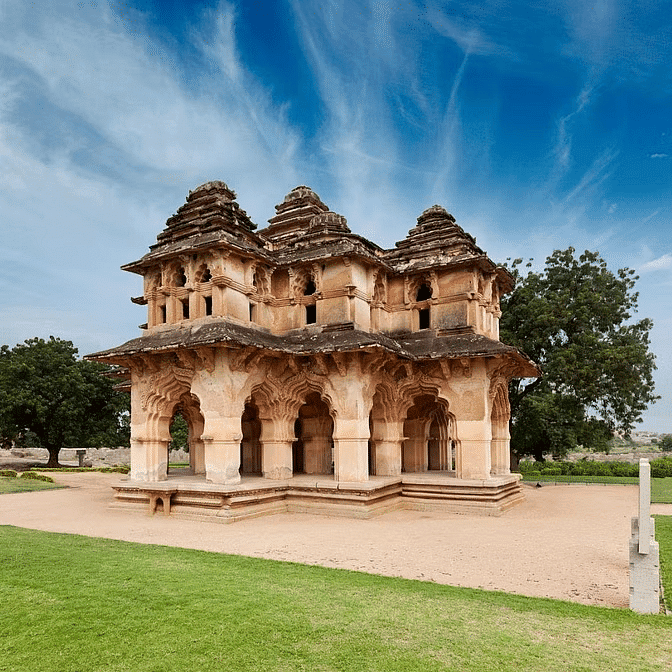

The Architectural Splendour of HampiHampi, situated in the Krishna-Tungabhadra basin, was the core of the Vijayanagara Empire founded in 1336. The ruins of Hampi showcase a well-fortified city with walls constructed without mortar, utilizing interlocking techniques.

- Hampi's distinctive architecture included splendid arches, domes, and pillared halls adorned with sculptures, surrounded by well-planned orchards and gardens featuring lotus and corbel motifs.

- During its peak in the fifteenth-sixteenth centuries, Hampi was a vibrant hub of commercial and cultural activities, attracting Muslim merchants, Chettis, and European traders like the Portuguese.

Exploring Hampi: UNESCO World Heritage site

Exploring Hampi: UNESCO World Heritage site - Temples, particularly the Virupaksha temple, played a central role in cultural events, hosting devadasis in many-pillared halls. The Mahanavami festival, akin to Navaratri, was a significant celebration.

- Vijayanagara rulers showed a keen interest in water management, constructing tanks and canals. Notable projects included the Anantraj Sagar Tank and a massive lake near Vijayanagara by Krishnadeva Raya, facilitating irrigation through aqueducts and channels.

- Hampi fell into ruin after the defeat of Vijayanagara in 1565 by the Deccani Sultans, rulers of Golconda, Bijapur, Ahmadnagar, Berar, and Bidar.

[Intext Question]

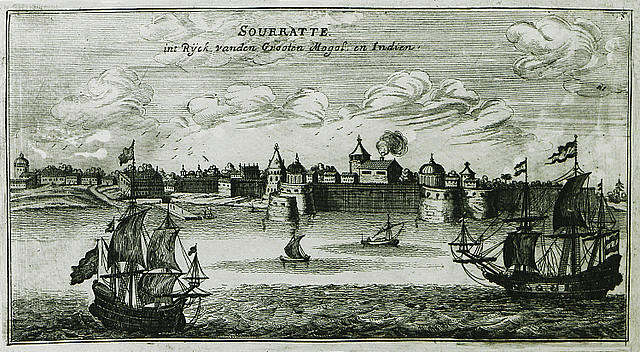

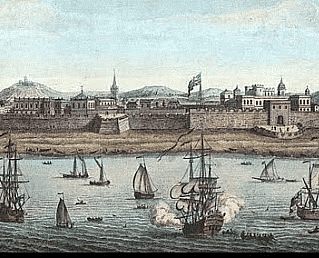

A Gateway to the West: Surat

Surat in Gujarat served as a major trading hub during the Mughal period, along with Cambay and Ahmedabad.

The city was a crucial gateway for trade with West Asia through the Gulf of Ormuz, earning the nickname "the gate to Mecca."

Surat was characterized by its cosmopolitan population, encompassing people of various castes and creeds.

During the seventeenth century, the Portuguese, Dutch, and English established factories and warehouses in Surat.

According to Ovington, an English chronicler, around a hundred ships from different countries could be found anchored at the port simultaneously.

Surat's renowned cotton textiles, featuring gold lace borders (zari), had a thriving market in West Asia, Africa, and Europe.

The city had numerous rest-houses to accommodate visitors from across the world, along with magnificent buildings and pleasure parks.

The Kathiawad seths or mahajans (moneychangers) operated significant banking houses in Surat.

The Surat hundis (bills of exchange) held respect in far-off markets like Cairo, Basra, and Antwerp.

Towards the end of the seventeenth century, Surat faced a decline due to factors such as the Mughal Empire's decline, Portuguese control of sea routes, and competition from Bombay (Mumbai).

Despite its historical decline, Surat remains a bustling commercial center today

Fishing in Troubled Waters: Masulipatnam

Located on the Krishna River delta, Masulipatnam was a crucial Fish Port Town in the seventeenth century.

Masulipatnam : Fish Port Town

Masulipatnam : Fish Port Town- Seventeenth-Century Activity: Attracting European East India Companies : The Dutch and English East India Companies vied for control of Masulipatnam due to its increasing importance.

- Dutch Fort at Masulipatnam: The Dutch constructed a fort in Masulipatnam in their efforts to establish dominance in the region.

- Qutb Shahi Rule and Royal Monopolies: Golconda's Qutb Shahi rulers enforced royal monopolies on various goods to prevent complete dominance by European trading companies.

- Diverse Trading Groups: A competitive environment involving Golconda nobles, Persian merchants, Telugu Komati Chettis, and European traders contributed to the city's prosperity.

- Mughal Annexation and Mir Jumla's Strategy: Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb's annexation of Golconda prompted Mir Jumla, a Mughal governor and merchant, to manipulate Dutch and English alliances for political advantage.

- Decline Triggered by Mughal Annexation: Following Golconda's annexation, European companies sought alternative trade centers as part of a new policy by the English East India Company.

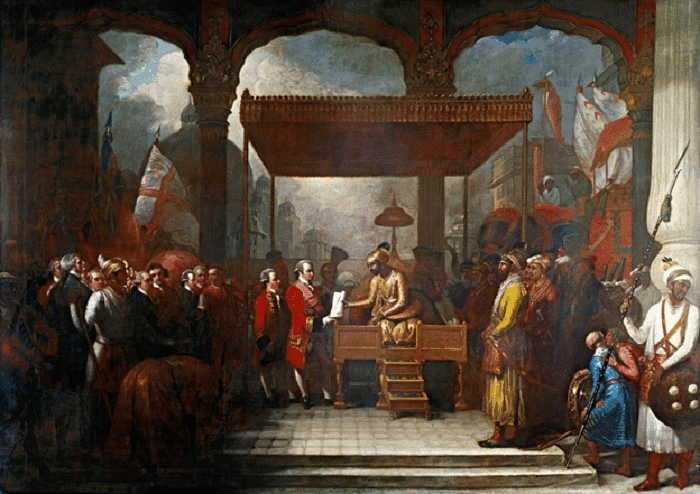

East India Company

East India Company - English East India Company's New Policy: The English East India Company aimed for its trade centers to serve political, administrative, and commercial purposes.

- Shift of English East India Company Traders: As the English East India Company traders moved to Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras, Masulipatnam lost both merchants and prosperity.

- Eighteenth-Century Decline: Masulipatnam experienced a decline in the eighteenth century, transforming from a prosperous port to a dilapidated town.

New Towns and Traders

In the 16th and 17th centuries, European countries sought spices and textiles, leading to the formation of East India Companies by the English, Dutch, and French. Initially, Indian traders like Mulla Abdul Ghafur and Virji Vora competed, but European naval power allowed them to control sea trade, making Indian traders work as their agents. Ultimately, the English became the dominant power. Virji Vora

Virji Vora

The demand for textiles led to the expansion of crafts like spinning and weaving, but it also marked the decline of craftspersons' independence. They had to work on advances, producing cloth promised to European agents and reproducing designs supplied by them.

The 18th century witnessed the rise of Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras as pivotal cities. Crafts and commerce underwent significant changes as merchants and artisans, including weavers, were confined to Black Towns established by European companies within these cities. Native traders and craftspersons resided there, while the ruling Europeans occupied superior residences in forts. The story of crafts and commerce in the 18th century will be explored further next year.

|

63 videos|371 docs|46 tests

|

FAQs on Class 7 History Notes - Towns, Traders And Craftspersons

| 1. What are the main administrative centres discussed in the article? |  |

| 2. How did temple towns and pilgrimage centres contribute to the economy? |  |

| 3. What was the significance of small towns in the trade network? |  |

| 4. Can you explain the roles of traders, both big and small, in the towns? |  |

| 5. What are the unique characteristics of Hampi, Masulipatnam, and Surat as trading towns? |  |