Class 9 History Chapter 2 Notes - Socialism in Europe and the Russian Revolution

The Age of Social Change

- In the last chapter, you learned how the French Revolution spread strong ideas about freedom and equality across Europe. This revolution made people think that it was possible to completely change the way society worked.

- Before the 1700s, society in Europe was mainly divided into groups called estates or orders, where the aristocrats (nobles) and the church had most of the power and wealth. But after the French Revolution, people began to believe that this unfair system could be changed.

French Revolution

French Revolution - However, not everyone in Europe agreed on how much change was needed. Some people thought a little change was okay, and it should happen slowly. Others believed society needed big changes immediately. People with different views were given different names:

- Conservatives wanted to keep things mostly the same.

- Liberals wanted change, but in a peaceful and gradual way.

- Radicals wanted quick and major changes.

In this chapter, you’ll learn about some important political ideas from the 19th century and how they led to social changes. Then we’ll study one major event — the Russian Revolution — where people tried to change society completely. This revolution helped spread the idea of socialism, which became very powerful in the 20th century.

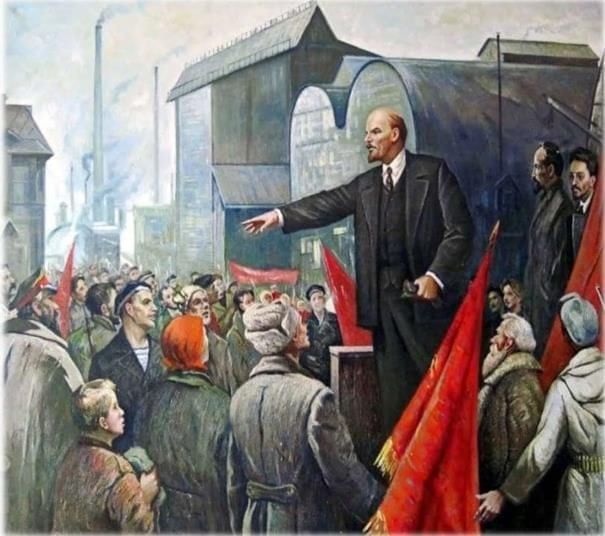

Lenin addressing workers during the Russian Revolution, symbolizing the rise of socialism and workers' rights.

Lenin addressing workers during the Russian Revolution, symbolizing the rise of socialism and workers' rights.

Liberals, Radicals, and Conservatives

During the nineteenth century, various groups in Europe had different ideas for bringing about change in society. These included liberals, radicals, and conservatives. Their beliefs and goals often clashed, especially in the period following the French Revolution.

One group that wanted to change society was called the liberals.

- They believed in religious tolerance, meaning all religions should be treated equally. At that time, many countries supported only one religion (e.g., Britain supported the Church of England, Austria and Spain supported the Catholic Church).

- Liberals were against the unlimited power of kings and dynasties.

- They wanted to protect individual rights.

- They supported the idea of a parliament elected by the people.

- They wanted clear laws and fair judges, not rulers controlling everything.

- However, liberals did not support democracy for all:

(a) They believed only men with property should be allowed to vote.

(b) They were against giving voting rights to women.

Radicals wanted deeper and more extensive changes in society. They believed:

- The government should represent the majority of the population.

- Women should have the right to vote, and many radicals supported women’s suffrage movements.

- The power of rich landowners and factory owners should be questioned.

- They supported private property but were against too much wealth being held by a few people.

Conservatives opposed both liberals and radicals. However, their views changed over time:

- In the eighteenth century, conservatives were strongly against any change and wanted to preserve the traditional order.

- After the French Revolution, even conservatives began to see the need for reform.

- By the nineteenth century, they accepted that some change was necessary, but believed it should happen gradually and with respect for traditions from the past.

These different political ideas led to various social and political conflicts in nineteenth-century Europe.

Industrial Society and Social Change

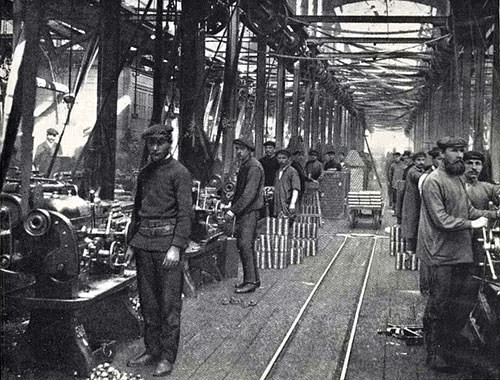

This period saw significant social and economic transformations. There was a rise of new cities, growth in industrial regions, expansion of railways, and the start of the Industrial Revolution.

- Industrialisation Problems: As industrialisation took off, many people, including men, women, and children, moved near factories. However, this progress came with serious drawbacks. Working hours were long, and wages were low. Unemployment was common, especially during times when demand for industrial goods was low. The rapid growth of towns led to urgent challenges regarding housing and sanitation.

An image of Russian Industrial Workers in the 1890s

An image of Russian Industrial Workers in the 1890s

- Solution by Radicals and Liberals: In response to the issues caused by industrialisation, liberals and radicals got together to look for solutions. They believed in supporting individual hard work and business, as an educated and healthy workforce would help society grow. This thinking attracted more support from the working class.

- Effects on the World: The ideas of radicals, liberals, and conservatives strongly shaped 19th-century society and politics. Their clashes and actions led to revolutions and national changes, which defined these movements and their limits.

Many nationalists and liberals aimed to change the governments set up in Europe after 1815. In countries like France, Italy, Germany, and Russia, they became revolutionaries, seeking to overthrow the existing monarchs. Nationalists spoke of revolutions that would create 'nations' where all citizens enjoyed equal rights. After 1815, Giuseppe Mazzini, an Italian nationalist, worked with others to achieve this in Italy. Nationalists in other regions, including India, read his writings.

The Coming of Socialism to Europe

One of the most powerful and far-reaching ideas for changing society in the 19th century was socialism. By the mid-1800s, socialism had become a well-known and widely discussed idea in Europe.

What Did Socialists Believe?

Socialists strongly opposed private property. They believed that private property was the main reason for many social problems at that time. This is because property—such as land, factories, and machines—was owned by a few individuals who focused only on earning personal profit. They paid little attention to the needs and welfare of the workers who actually helped make the property productive.

Socialists believed that if property was owned and managed by society as a whole, then more attention would be paid to the well-being of everyone, not just a few individuals. They wanted to build a system where the focus was on the collective good of all people. To bring this change, they campaigned and shared their ideas widely.

Different Visions Within Socialism

Not all socialists agreed on how a socialist society should be created. They had different ideas about how to achieve this goal.

Robert Owen's Idea of Cooperative Society

Robert Owen (1771–1858) was a well-known English manufacturer. He believed in creating cooperative communities, where people would live and work together and share the profits. He tried to build such a community called New Harmony in Indiana, USA.

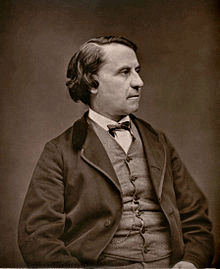

Louis Blanc and Government Support for Cooperatives

Louis Blanc (1813–1882), a socialist thinker from France, had a different view. He believed that cooperative societies could not be set up on a large scale by individuals alone. He argued that the government should take the lead in promoting cooperatives and replacing capitalist businesses. In his view, cooperatives should be groups of people working together to produce goods and sharing profits based on the work each member contributed.

Louis Blanc

Louis Blanc

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: A Radical View

Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) introduced a more radical version of socialism. Marx believed that industrial society was based on capitalism, where capitalists (the factory and property owners) invested money and made profits from the hard work of laborers.

Marx argued that workers would never be able to improve their condition as long as capitalists continued to earn profits from their labour. The only way to bring change, according to him, was for workers to overthrow the capitalist system and end private ownership of property.

He believed that a truly fair society could only be created when all property was collectively owned and managed by society. Marx called this ideal a communist society. In such a society, there would be no private property, no exploitation, and everyone would have equal rights.

In conclusion, socialism introduced a new way to think about society. It questioned private ownership and suggested sharing resources and profits for everyone’s benefit. These ideas inspired many political movements, and events like the Russian Revolution made socialism a major force in the 20th century.

Support for Socialism

By the 1870s, socialist ideas were spreading across Europe. An international organisation called the Second International was formed. Workers in England and Germany began establishing associations to campaign for better living and working conditions. They set up funds to assist members in times of need and demanded:

- A reduction in working hours

- The right to vote

In Germany, the Social Democratic Party gained parliamentary seats. By 1905, socialists and trade unionists had established a Labour Party in Britain and a Socialist Party in France. While their ideas influenced legislation, governments continued to be led by conservatives, liberals, and radicals.

The Russian Revolution

Russia was one of the least industrialised countries in Europe, but something unusual happened there. In 1917, the socialists took control of the government during what is known as the October Revolution. Earlier that same year, the Russian king (Tsar) had lost his throne in February. These two big events—the fall of the monarchy in February and the socialist takeover in October—are together known as the Russian Revolution.

But how did all this happen? What was life like in Russia before the revolution? Let’s find out by looking at the conditions in Russia a few years earlier.

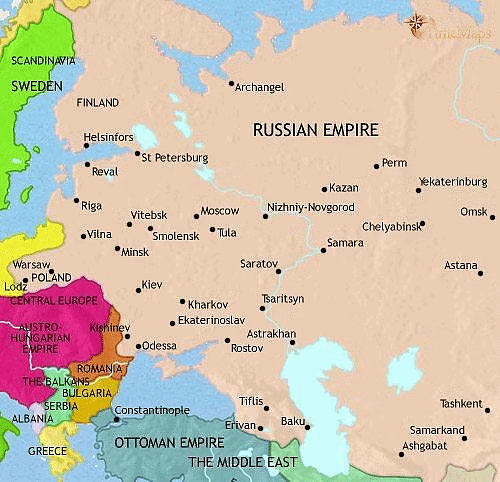

The Russian Empire in 1914

- In 1914, Tsar Nicholas II ruled over Russia and its large empire. This included areas around Moscow, as well as present-day Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, parts of Poland, Ukraine, and Belarus. The empire stretched to the Pacific Ocean and included today’s Central Asian nations, along with Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan.

- The main religion was Russian Orthodox Christianity, which evolved from the Greek Orthodox Church, but there were also followers of Catholicism, Protestantism, Islam, and Buddhism.

- Russia followed the Julian calendar until 1st February 1918. The country then switched to the Gregorian calendar, which is the standard today.

- The Gregorian dates are 13 days ahead of the Julian dates, meaning the 'February' Revolution happened on 12th March, and the 'October' Revolution occurred on 7th November.

- Russia was an autocracy. Unlike many other European leaders at the beginning of the 20th century, the Tsar was not accountable to a parliament. This lack of political representation played a significant role in the unrest that led to the revolution.

Economy and Society

- Agriculture Dominance: In the early 20th century, around 85% of the population worked in agriculture. Russia had a larger share of people reliant on farming compared to most European nations.

- Industrial Development: Industrialisation was primarily found in cities like St Petersburg and Moscow. Both craftsmen and large factories existed side by side, with significant factory growth in the 1890s. Russia became a leading exporter of grain. The expansion of the railway system and foreign investments during the 1890s boosted industrial growth, with coal production doubling and iron and steel output increasing fourfold.

- Working Conditions: Most industries were owned by private individuals. The government attempted to ensure minimum wages and limit working hours, but factory inspectors often faced challenges enforcing these rules. Many workers dealt with long hours, and living conditions varied greatly.

- Social Divisions Among Workers: The year 1904 was very difficult for Russian workers. Prices of basic goods rose fast, and real wages fell by 20%. Workers were socially divided based on their village ties, how long they had lived in cities, and their skill levels. Women constituted 31% of the workforce, yet earned less than their male counterparts. Some workers formed associations to support each other during times of unemployment or financial struggles, but these were few in number. Even with social differences, workers often came together to strike over job losses or poor working conditions. Frequent strikes occurred in the textile industry during 1896-1897 and in the metal industry in 1902.

- Peasant Conditions: Many unemployed peasants relied on charitable kitchens for food and lived in poor conditions. The poor living situations of peasants contributed to the social unrest that started the revolution.

- Impact of World War I: Initially, the war was popular in Russia, with people supporting Tsar Nicholas II. However, as the conflict dragged on, the Tsar's refusal to consult the main political parties in the Duma led to growing dissatisfaction among the general population.

Russian Empire in 1914

Russian Empire in 1914

- Peasants and Land Ownership:

a) Peasants worked the majority of the land, while large estates were owned by the nobility, the crown, and the Orthodox Church.

b) Russian peasants were very religious, but they generally had no respect for the nobility, who gained their power through their services to the Tsar, not through local popularity.

c) They demanded land redistribution and often refused to pay rent, with some even resorting to murdering landlords. This trend became widespread in southern Russia in 1902 and spread across the country in 1905.

d) Unlike other European peasants, Russian peasants periodically pooled their land together, and their commune (mir) allocated it based on the needs of individual families.

Socialism in Russia

- Before 1914, the government in Russia banned all political parties, forcing the Russian Social Democratic Workers Party (RSDWP) to function as an illegal group.

- The RSDWP was established in 1898 by socialists who followed Marx's principles, organising strikes, mobilising workers secretly, and creating a newspaper.

- Some socialists viewed Russian peasants, with their tradition of sharing land, as natural socialists who could lead the revolution.

- This belief led to the formation of the Socialist Revolutionary Party in 1900, which advocated for peasant rights and land redistribution from nobles to peasants.

- The Socialist Revolutionary Party focused on issues affecting peasants, while Lenin and the Social Democrats believed peasants were divided.

- Lenin argued that differences among peasants, such as wealth and roles in labour, prevented them from being a unified revolutionary force.

- Lenin’s Bolsheviks preferred a tightly controlled, disciplined party to withstand Tsarist repression.

- In contrast, the Mensheviks supported a more open membership model like that of the German socialist movement.

A Turbulent Time: The 1905 Revolution

- Russia was an autocracy, with the Tsar holding all power.

- In 1905, liberals, socialists, peasants, and workers united to demand a constitution. Rising prices and falling wages in 1904 worsened worker struggles. They gained support from nationalists in the empire, such as poland and Muslim reformers.

- In the Bloody Sunday incident, police and Cossacks attacked unarmed workers led by Father Gapon, resulting in over 100 deaths and around 300 injuries.

- The 1905 Revolution sparked widespread unrest, including strikes, student walkouts, and the formation of the Union of Unions, which called for a constituent assembly.

- The Tsar temporarily allowed the formation of a consultative Parliament (Duma) and permitted trade unions and factory committees to operate briefly.

- After the revolution, the Tsar limited the Duma, dismissing the first two within months and altering voting laws to ensure a conservative majority in the third Duma.

- Political repression resumed, with the Tsar banning most political activities to silence liberals and revolutionaries.

The First World War and the Russian Empire

- In 1914, a war began in Europe between two groups of countries: Germany, Austria, and Turkey on one side, and France, Britain, and Russia on the other.

- Later, countries like Italy and Romania also joined the war, which was fought in many parts of the world due to the European colonies.

- This global conflict came to be known as the First World War.

- In Russia, many people initially supported the war and hoped it would make their country proud.

- However, the Tsar (King of Russia) took all major decisions himself without consulting the Duma (the elected Parliament), which made people unhappy.

- Anti-German feelings grew strong in Russia, so the capital city’s name was changed from St Petersburg (which sounded German) to Petrograd.

- The Tsarina (queen), Alexandra, was German by birth. Her close friendship with a monk named Rasputin, who influenced royal decisions, made the royal family very unpopular.

- On the western front of the war (in places like France), soldiers stayed in deep trenches and fought from there.

- On the eastern front (Russia’s side), armies moved around more, and there were very heavy losses.

- Between 1914 and 1916, the Russian army suffered huge defeats from Germany and Austria.

- Over 7 million Russian soldiers were killed, wounded, or taken as prisoners of war by 1917.

- As Russian troops retreated, they destroyed crops and buildings so that the enemy could not use them, which led to more than 3 million people becoming homeless refugees.

- These disasters made the Russian people very angry with their government.

- Most soldiers had lost the will to fight and no longer believed in the war.

- Russia had very few industries, and during the war, it could not get help from its allies because Germany blocked trade routes like the Baltic Sea.

- As a result, machines broke down quickly and were not repaired or replaced.

- By 1916, the railway system in Russia had started to fail.

- Many workers were sent to fight in the army, so there were not enough people left to run the factories.

- Small workshops and industries had to close down due to a shortage of workers and materials.

- Grain was being sent mainly to feed the soldiers at the front, leaving people in the cities with very little food.

- By the winter of 1916, there was so little bread and flour available that people were rioting outside bread shops.

The February Revolution in Petrograd

- The winter of 1917 was tough for the people of Petrograd. The city was divided, with workers living in the poorer areas on the right bank of the River Neva, while the left bank had the more affluent districts, the Winter Palace, and government buildings, including where the Duma met.

- Food shortages were a major issue, especially in the workers' areas. The effects of World War I had severely disrupted grain supplies, resulting in a lack of bread and flour. By winter 1916, riots over bread were common.

- Tensions rose as the government faced opposition from parliament members who wanted to maintain the elected government, while the Tsar aimed to dissolve the Duma.

- On 22 February, there was a lockout at a factory on the right bank. The next day, workers from fifty factories went on strike in support. Women were prominent in these protests; at the Lorenz telephone factory, Marfa Vasileva played a key role in organising a successful strike. In honour of International Women's Day, women workers gave red bows to their male colleagues, motivating them.

- After the initial protests, demonstrators regrouped on the 24th and 25th. On 25 February, the government suspended the Duma, leading to a resurgence of protests on the left bank of Petrograd the next day, with people demanding better conditions.

- On 27 February, the Police Headquarters was attacked, and the streets were filled with calls for bread, wages, better working hours, and democracy. Despite government attempts to suppress the protests, the cavalry refused to attack the demonstrators. This change in loyalty was crucial; when the Imperial Russian army began to support the revolutionaries, the Tsarist regime fell apart.

- Eventually, soldiers and striking workers united to form a council called the Petrograd Soviet in the same building where the Duma convened. Military leaders urged the Tsar to step down, which he did on 2 March.

- Leaders from the Soviet and the Duma created a Provisional Government to manage the country, effectively ending the monarchy in what is known as the February Revolution. The future of Russia would be determined by a constituent assembly elected based on universal adult suffrage.

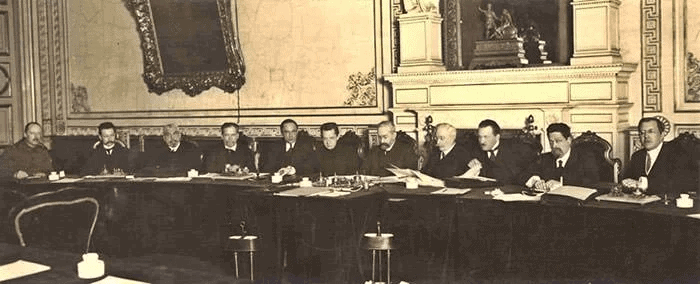

Russian Provisional Government in March 1917

Russian Provisional Government in March 1917

After February

- Army officials, landowners, and industrialists held significant power in the Provisional Government. However, both the liberals and socialists among them aimed for an elected government.

- Restrictions on public meetings and associations were lifted.

- In April 1917, Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the Bolsheviks, returned to Russia from exile.

- He and the Bolsheviks had been against the war since 1914.

- Lenin announced his ‘April Theses’, which called for an end to the war, land to be given to the peasants, and the nationalisation of banks. These were Lenin's core demands.

- Initially, most in the Bolshevik Party were taken aback by the April Theses. They believed it was too early for a socialist revolution and that the Provisional Government should be supported. However, events in the following months shifted their views.

- The workers’ movement continued to grow throughout the summer, leading to the creation of factory committees and trade unions, as well as soldier committees within the army.

- In June, approximately 500 Soviets sent delegates to an All-Russian Congress of Soviets. There was no uniform system of election for these Soviets.

- As Bolshevik influence expanded and the Provisional Government weakened, the latter took harsh actions against the rising discontent, arresting leaders and resisting workers’ attempts to manage factories.

- In July 1917, the Bolsheviks organised popular demonstrations that were seemingly suppressed, forcing many of their leaders to go into hiding or flee.

The Revolution of October 1917

- Lenin grew increasingly worried that the Provisional Government might establish a dictatorship as tensions between them and the Bolsheviks heightened.

- In September, he began preparations for a rebellion against the government, rallying Bolshevik supporters from the army, Soviets, and factories.

- On 16 October 1917, Lenin convinced the Petrograd Soviet and the Bolshevik Party to endorse a socialist seizure of power. A Military Revolutionary Committee was appointed by the Soviet, led by Leon Trotskii, to plan the takeover. The date of the uprising was kept secret.

- The uprising commenced on 24 October. Anticipating unrest, Prime Minister Kerenskii left the city to call for troops. At dawn, military forces loyal to the government captured the offices of two Bolshevik newspapers.

- Government troops were dispatched to seize telephone and telegraph offices and to guard the Winter Palace.

- Later that day, the ship Aurora bombarded the Winter Palace, allowing the committee to capture the city and leading to the ministers' surrender.

- During a Petrograd meeting of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets, the majority supported the Bolshevik actions.

- Uprisings also occurred in other cities, with intense fighting, particularly in Moscow.

- By December, the Bolsheviks had gained control over the Moscow-Petrograd region.

The Petrograd Soviet, the banner on the left reads, "Down with Lenin and Co."

The Petrograd Soviet, the banner on the left reads, "Down with Lenin and Co."

What Changed After October?

- Private property was strongly opposed by the Bolsheviks (This was in alignment with Marxist ideology), who nationalised most industries and banks in November 1917. They also allowed peasants to take land from the nobility.

- They enforced the division of large homes in cities and prohibited the use of aristocratic titles.

- The army and officials received new uniforms to signify the change.

- The Bolshevik Party was renamed the Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik). In November 1917, they held elections for the Constituent Assembly but did not secure majority support.

- The Assembly rejected Bolshevik proposals, resulting in its dismissal by Lenin in January 1918.

- Despite opposition from political allies, the Bolsheviks signed a peace treaty with Germany at Brest Litovsk in March 1918.

- In the following years, the Bolsheviks became the only party to participate in elections for the All Russian Congress of Soviets, which evolved into the country's Parliament, establishing Russia as a one-party state.

The Civil War

- After the Bolsheviks ordered land redistribution, the Russian army broke apart, with soldiers—mostly peasants—deserting the army to return home and claim redistributed land.

- Opponents of the Bolsheviks—like other socialists, liberals, and royalists—rejected the uprising. Their leaders gathered in southern Russia to form armies against the Bolsheviks, with support from France, America, Britain, and Japan, who feared the spread of socialism.

- During 1918 and 1919, the Socialist Revolutionaries (known as "greens") and pro-Tsarists (referred to as "whites") controlled most of the Russian empire. As these troops fought the Bolsheviks in a civil war, looting, banditry, and famine became widespread.

- Supporters of private property among the "whites" took severe actions against peasants who had seized land, leading to a loss of popular support for the non-Bolsheviks.

- By January 1920, the Bolsheviks had taken control of most of the former Russian empire. To gain support, they granted political autonomy to non-Russian nationalities in the Soviet Union (USSR), established by the Bolsheviks from the Russian empire in December 1922. However, their attempts to win over different nationalities were only partially successful, as they enforced unpopular policies on local governments, such as the harsh discouragement of nomadism.

Making a Socialist Society

- During the civil war, the Bolsheviks kept control over industries and banks by nationalising them (bringing them under government control).

- Peasants were allowed to farm on the land that had been taken over by the government (socialised land).

- The confiscated land was used to show how people could work together (collective farming).

- The government started centralised planning, where officials decided how the economy should function and set goals for five years at a time.

- These goals were known as Five Year Plans.

- The government fixed prices of goods to encourage faster industrial growth, especially during the first two plans (1927–1932 and 1933–1938).

- This type of planning led to economic growth. For example, production of oil, coal, and steel doubled between 1929 and 1933.

- Many new industrial cities were built.

- However, because construction was done quickly, working conditions were poor.

- In the new city of Magnitogorsk, a steel plant was built in just three years, but workers faced a lot of hardship.

- In the first year alone, there were 550 strikes due to poor conditions.

- Living conditions were also tough — in winter, people had to go outside in freezing cold (–40°C) just to use the toilet.

- The government started schools and gave opportunities for workers and peasants to go to universities.

- Childcare centres (crèches) were set up in factories for children of women workers.

- Low-cost public health care was provided.

- Model homes were made for workers.

- But not everyone benefited equally because government funds were limited, so the results were uneven.

Stalinism and Collectivization

- Context of Early Planned Economy: In the late 1920s, Soviet towns faced serious grain shortages as government price controls led peasants to withhold their grain, showing the flaws in early Soviet economic policies.

- Stalin’s Emergency Measures: After Lenin’s death, Stalin took over and blamed wealthy peasants, or "kulaks", for hoarding grain. He enforced strict grain collections, with party members raiding kulaks to obtain food supplies.

- The Collectivization Program: It was argued that grain shortages were partly due to the small size of holdings. Stalin launched collectivization in 1929, forcing peasants into state-controlled farms (kolkhozes) to modernise agriculture. Peasants shared land, tools, and profits under state supervision.

- Resistance and Consequences: Many peasants resisted collectivization by destroying their livestock, leading to a significant drop in cattle numbers. Resistance was met with harsh punishment, and independent farming was pushed to the margins.

- Impact, Criticism, and Repression: Collectivization resulted in a devastating famine (1930-1933), causing millions of deaths. Criticism within the party arose, but Stalin responded with severe repression, imprisoning or executing over 2 million people by 1939.

The Global Influence of the Russian Revolution and the USSR

- Many socialist parties in Europe did not fully support the way the Bolsheviks took and held power in Russia.

- Despite this, the idea of a government run by workers excited people across the world.

- This led to the formation of communist parties in different countries, such as the Communist Party of Great Britain.

- The Bolsheviks encouraged people in colonies to try similar revolutions.

- People from outside Russia attended events like the Conference of the Peoples of the East (1920) and joined the Comintern – a worldwide organisation of pro-Bolshevik socialist parties.

- Some non-Russian supporters studied in the Communist University of the Workers of the East, located in the USSR.

- By the time World War II began, the USSR had become a symbol of socialism worldwide.

- However, by the 1950s, people in the USSR began to realise that their government did not fully follow the values of the Russian Revolution.

- Around the world, socialist supporters also noticed that things were not ideal in the Soviet Union.

- The USSR had transformed from a poor country into a powerful nation.

- It improved its industries and farming, and provided food for the poor.

- But the government took away basic freedoms and used harsh methods to carry out development.

- By the late 20th century, the USSR’s global image as a socialist country had weakened.

- Still, socialist ideas remained popular among many people.

- Different countries began thinking about socialism in their own unique ways.

Difficult Words

- Suffragette movement: A movement to give women the right to vote.

- Jadidists: Muslim reformers within the Russian Empire.

- Real wage: Reflects the amounts of goods that wages can buy.

- Autonomy: The right to govern themselves.

- Nomadism: A lifestyle of people who move from place to place to earn a living.

- Deported: Forcibly removed from one’s own country.

- Exiled: Forced to live away from one’s own country.

- Aristocracy: A class of people with special rank and privileges, especially the hereditary nobility.

- Dynastic: Related to a dynasty, a sequence of rulers from the same family.

- Franchise: The right to vote in public elections.

- Judiciary: The judges of a country; judicial authorities collectively.

- Cooperatives: Enterprises owned by and operated for the benefit of those using their services.

- Autocracy: A government system where one person has absolute power.

- Provisional: Existing for the present, possibly to change later.

- Soviet: A governing council in the former Soviet Union, usually elected from workplaces or army units.

- Constituent: A part of a whole; a component.

- Kulaks: Wealthy peasants in the Soviet Union who owned larger farms and used hired labour; they were targeted during Stalin's forced collectivisation.

- Collective farms (kolkhoz): Agricultural cooperatives in the Soviet Union where land and equipment were pooled for collective farming.

- Planned Economy: An economic system where the government controls and regulates production, distribution, and prices.

Some Important Dates

- 1850s - 1880s: Debates over socialism in Russia.

- 1898: Formation of the Russian Social Democratic Workers Party.

- 1905: Bloody Sunday and the Revolution of 1905.

- 1917: 2nd March - Abdication of the Tsar; 24th October - Bolshevik uprising in Petrograd.

- 1918-20: The Civil War.

- 1919: Formation of the Comintern.

- 1929: Beginning of Collectivisation.

Note on Calendar Change: Russia followed the Julian calendar until 1 February 1918. It then changed to the Gregorian calendar, which is used everywhere today. The Gregorian dates are 13 days ahead of the Julian dates. Thus, according to our calendar, the 'February' Revolution took place on 12th March and the 'October' Revolution on 7th November.

Context on Conditions in 1904: The year 1904 was particularly difficult for Russian workers. Prices of essential goods rose quickly, leading to a 20% decline in real wages.

|

55 videos|635 docs|79 tests

|

FAQs on Class 9 History Chapter 2 Notes - Socialism in Europe and the Russian Revolution

| 1. What were the main causes of the Russian Revolution? |  |

| 2. How did the February Revolution differ from the October Revolution? |  |

| 3. What were the major changes in Russia after the October Revolution? |  |

| 4. What was the global impact of the Russian Revolution? |  |

| 5. How did socialism evolve in Europe after the Russian Revolution? |  |