Atoms | Physics Class 12 - NEET PDF Download

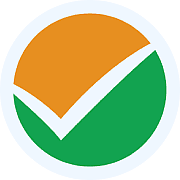

Thomson’s Atomic Model

- Every atom is uniformly positive charged sphere of radius of the order of 10-10 m, in which entire mass is uniformly distributed and negative charged electrons are embedded randomly.

- The atom as a whole is neutral.

Thomson's atomic model

Thomson's atomic model

Limitations of Thomson’s Atomic Model

- It could not explain the origin of spectral series of hydrogen and other atoms.

- It could not explain large angle scattering of α – particles.

Rutherford's Nuclear Model of an Atom

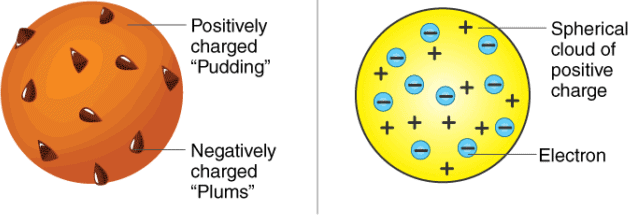

- In 1911, Rutherford, along with Geiger and Marsden, conducted the Alpha Particle scattering experiment.

- This experiment marked the inception of the 'nuclear model of an atom,' reshaping our understanding of atomic structure.

The Alpha Particle Scattering Experiment

- They conducted an experiment using a thin gold foil placed in the center of a rotatable detector made of zinc sulfide and a microscope.

- A beam of 5.5MeV alpha particles from a radioactive source was directed at the foil, collimated by lead bricks.

- Scattering of alpha particles could be observed by flashes on the screen post-collision.

Alpha Particle Scattering Experiment

Alpha Particle Scattering Experiment

Observations

- Majority of alpha particles passed through the foil without collisions.

- Approximately 0.14% of alpha particles scattered by more than 1 degree.

- Around 1 in 8000 alpha particles deflected by more than 90 degrees.

Conclusions and Arguments

- Results conflicted with Thomson's plum-pudding model of the atom.

- Rutherford proposed a concentrated positive charge at the atom's center based on deflection observations.

The Experiment by Rutherford

- Incident Alpha Particle and Deflection

When the incident alpha particle approaches the positive mass at the center of the atom closely, it experiences repulsion, leading to deflection. Conversely, if it passes at a considerable distance from this mass, there is no deflection; it simply continues through.

- Nuclear Model of an Atom

Rutherford introduced the 'nuclear model of an atom,' where the nucleus contains most of the positive charge and mass. Electrons orbit around the nucleus like planets around the sun. His experiments suggested the nucleus's size ranges from about 10-15 m to 10-14 m.

- Size Discrepancy and Atom Structure

The Kinetic theory indicates that an atom measures about 10-10 meters, which is roughly 10,000 to 100,000 times larger than the nucleus. Therefore, electrons appear to be around 10,000 to 100,000 times the size of the nucleus away from it.

- Empty Space in Atoms

The experiment highlighted that most of an atom comprises empty space, explaining why a significant number of alpha particles passed through the foil. When alpha particles come close to the nucleus, they get deflected or scattered at wide angles. Since electrons have minimal mass, they do not alter the path of these incident alpha particles.

Alpha Particle Trajectory

- Alpha particles are the nuclei of helium atoms, possessing two units of positive charge (2e) and the mass of a helium atom.

- The path of an alpha particle is influenced by the impact parameter, which is the shortest distance from the centre of the nucleus.

- When alpha particles in a beam have the same kinetic energy, their scattering is determined only by the impact parameter.

- Alpha particles with a small impact parameter (close to the nucleus) experience significant scattering, often at large angles.

- In contrast, those with a large impact parameter move nearly straight with little deflection.

- Alpha particles that approach with nearly zero impact parameter collide head-on with the nucleus and bounce back.

- Only about 0.14% of incident alpha particles scatter by more than 1°, and roughly 1 in 8000 deflect by more than 90°.

- The small number of particles that bounce back suggests that few alpha particles collide head-on.

- This indicates that the mass and positive charge of the atom are concentrated in a small volume.

Distance of Closest Approach

- As an alpha (α) particle gets closer to the nucleus, the positive charge of the nucleus pushes back with a strong electrostatic force.

- This push causes the kinetic energy of the α-particle to change into electrostatic potential energy.

- At a certain closest distance r0, all the kinetic energy becomes potential energy, stopping the α-particle from getting any nearer. This distance is called the distance of closest approach.

Calculating the Distance of Closest Approach

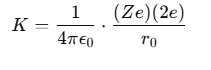

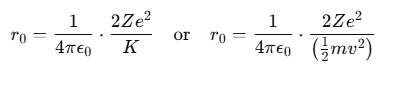

At the distance of closest approach, the kinetic energy (KE) of the α-particle is equal to its electrostatic potential energy. The relationship can be expressed as:

where:

- The charge on the α-particle is +2e,

- The charge on the nucleus is Ze (where Z is the atomic number).

From this, the formula for r0 can be derived as:

where:

- m represents the mass of the α-particle,

- v is the initial velocity of the α-particle.

From this formula, it is evident that the distance of closest approach between the α-particle and the nucleus is influenced by the kinetic energy of the α-particle.

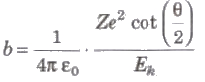

Impact Parameter (b)

The perpendicular distance of the velocity vector of a-particle from the central line of the nucleus, when the particle is far away from the nucleus is called impact parameter.

Impact parameter,

where, Z = atomic number of the nucleus, Ek = kinetic energy of the c-particle and θ = angle of scattering.

Limitations of Rutherford Atomic Model

- About the Stability of Atom: According to Maxwell’s electromagnetic wave theory electron should emit energy in the form of electromagnetic wave during its orbital motion. Therefore. radius of orbit of electron will decrease gradually and ultimately it will fall in the nucleus.

- About the Line Spectrum: Rutherford atomic model cannot explain atomic line spectrum.

Electron Orbits

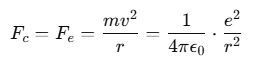

The Rutherford model of the atom describes it as a neutral sphere composed of a very small, dense, positively charged nucleus at the center, surrounded by electrons moving in dynamically stable orbits.

These electrons remain in orbit due to the electrostatic force of attraction Fe between the negatively charged electrons and the positively charged nucleus, which acts as the required centripetal force Fc to maintain the orbit.

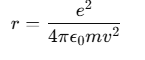

For a stable orbit in a hydrogen (H) atom:

Since Z=1 for hydrogen, the relationship between the radius of the orbit r and the electron velocity v can be expressed as:

Energy of an Electron in the H Atom

The kinetic energy K of the electron and its electrostatic potential energy U in the hydrogen atom can be given by:

(The negative sign in U indicates that the electrostatic force is attractive, directed towards the nucleus.)

Thus, the total mechanical energy E of the electron in the hydrogen atom is:

The negative total energy E signifies that the electron is bound to the nucleus. If E were positive, the electron would not follow a closed orbit and would escape from the atom.

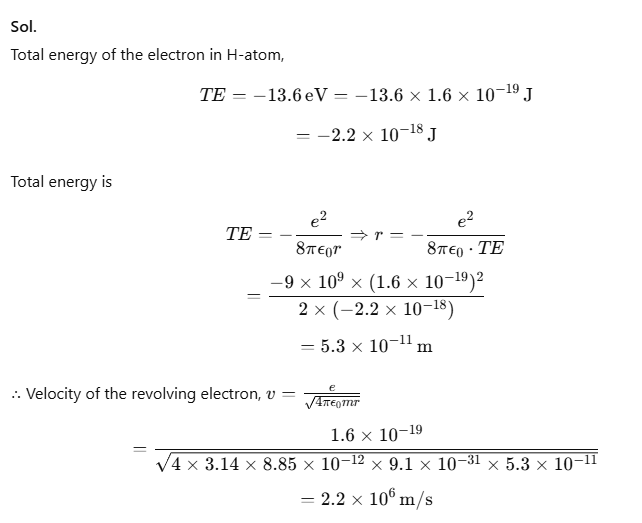

Example 1. It is found experimentally that 13.6 eV energy is required to separate a H-atom into a proton and an electron. Compute the orbital radius and velocity of the electron in a H-atom.

Atomic Spectra

- All condensed matter (solids, liquids, and dense gases) emit electromagnetic radiation at all temperatures.

- This radiation has a continuous distribution of several wavelengths with different intensities.

- This is caused by oscillating atoms and molecules and their interaction with the neighbours.

- In the early nineteenth century, it was established that each element is associated with a characteristic spectrum of radiation, known as Atomic Spectra.

- Hence, this suggests an intimate relationship between the internal structure of an atom and the spectrum emitted by it.

- When an atomic gas or vapour is excited under low pressure by passing an electric current through it, the spectrum of the emitted radiation has specific wavelengths.

- It is important to note that such a spectrum consists of bright lines on a dark background.

- This is an emission line spectrum.

Here is an emission line spectrum of hydrogen gas:

- The emission line spectra work as a ‘fingerprint’ for identification of the gas.

- Also, on passing a white light through the gas, the transmitted light shows some dark lines in the spectrum.

- These lines correspond to those wavelengths that are found in the emission line spectra of the gas.

- This is the absorption spectrum of the material of the gas.

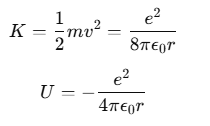

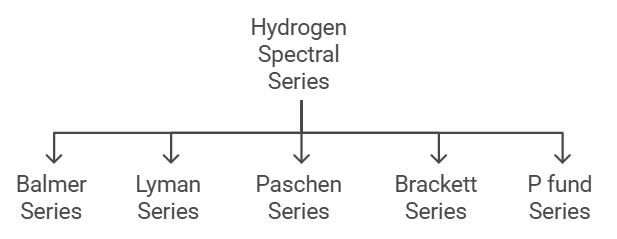

Spectral Series of Atomic Spectra

- Normally, one would expect to find a regular pattern in the frequencies of light emitted by a particular element.

- Let’s look at hydrogen as an example. Interestingly, at the first glance, it is difficult to find any regularity or order in the atomic spectra.

- However, on close observation, it can be seen that the spacing between lines within certain sets decreases in a regular manner.

- Each of these sets is a spectral series.

Five spectral series identified in hydrogen are

Further, let’s look at the Balmer series in detail.

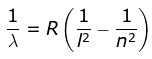

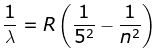

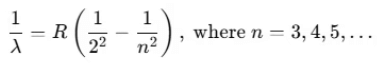

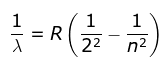

1. Balmer Series

In 1885, when Johann Balmer observed a spectral series in the visible spectrum of hydrogen, he made the following observations:

- The longest wavelength is 656.3 nm

- The second longest wavelength is 486.1 nm

- And the third is 434.1 nm

- Also, as the wavelength decreases the lines appear closer together and weak in intensity

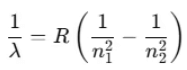

- He found a simple formula for the observed wavelengths:

where λ is the wavelength

R is the Rydberg's constant and

n can have any integral value.

Further, for n=∞, you can get the limit of the series at a wavelength of 364.6 nm. Also, you can’t see any lines beyond this; only a faint continuous spectrum. Furthermore, like the Balmer’s formula, here are the formulae for the other series:

2. Lyman Series

where λ is the wavelength

R is the Rydberg's constant and

n can have any integral value.

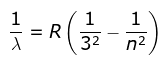

3. Paschen Series

where λ is the wavelength

R is the Rydberg's constant and

n can have any integral value

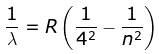

4. Brackett Series

where λ is the wavelength

R is the Rydberg's constant and

n can have any integral value

5. P fund Series

where λ is the wavelength

R is the Rydberg's constant and

n can have any integral value

Spectral Series of Atomic Spectra

Spectral Series of Atomic Spectra

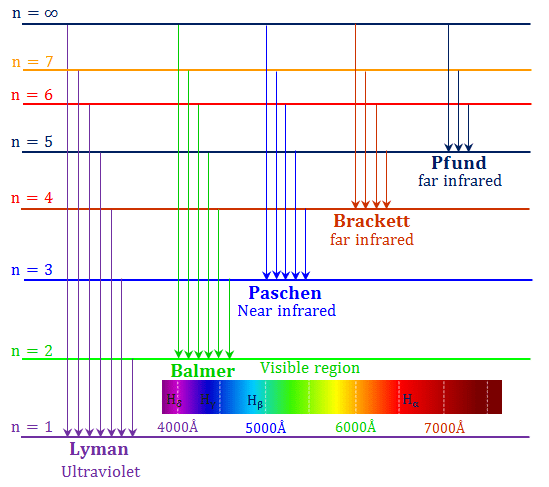

Bohr's Model of the Hydrogen Atom

Bohr combined classical and early quantum theories and presented his model of the hydrogen atom with three postulates:

1. Bohr’s First Postulate

An electron in an atom can move in specific stable orbits without radiating energy, which contradicts the predictions of classical electromagnetic theory. According to this postulate, each atom has a set of definite, stable energy states in which it can exist. Each possible state has a specific total energy and is referred to as a stationary state of the atom.

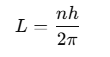

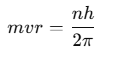

2. Bohr’s Second Postulate

The electron orbits the nucleus only in orbits where its angular momentum is an integer multiple of

where h is Planck’s constant (6.63 x 10−34 J·s). Thus, the angular momentum L of the orbiting electron is quantized and is given by:

where n is a positive integer known as the principal quantum number. As the angular momentum of an electron is mvr, for any permitted (stationary) orbit, we have:

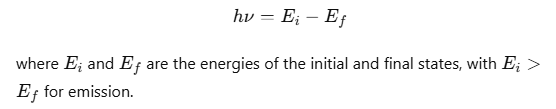

3. Bohr’s Third Postulate

An electron can transition between specified non-radiating orbits by emitting or absorbing a photon with energy equal to the difference between the initial and final energy levels. The frequency ν of the emitted photon is given by:

Bohr's Theory

Electron can revolve in certain non-radiating orbits called stationary or bits for which the angular momentum of electron is an integer multiple of (h / 2π)

- mvr = nh / 2π

where n = I, 2. 3,… called principle quantum number.

Bohr's Atomic Model

Bohr's Atomic Model

- The radiation of energy occurs only when any electron jumps from one permitted orbit to another permitted orbit.

- Energy of emitted photon, hv = E2 – E1, where E1 and E2are energies of electron in orbits.

- Radius of orbit of electron is given by

r = n2h2 / 4π2 mK Ze2

⇒ r ∝ n2 / Z,

where,

n = principle quantum number,

h = Planck’s constant,

m = mass of an electron,

K = 1 / 4 π ε,

Z = atomic number and

e = electronic charge. - Velocity of electron in any orbit is given by

v = 2πKZe2 / nh

⇒ v ∝ Z / n - Frequency of electron in any orbit is given by

v = KZe2 / nhr - Kinetic energy of electron in any orbit is given by

Ek = 2π2me4Z2K2 / n2 h2 = 13.6 Z2 / n2 eV - Potential energy of electron in any orbit is given by

Ep = – 4π2me4Z2K2 / n2 h2 = 27.2 Z2 / n2 eV

⇒ Ep = ∝ Z2 / n2 - Total energy of electron in any orbit is given by

E = – 2π2me4Z2K2 / n2 h2 = – 13.6 Z2 / n2 eV

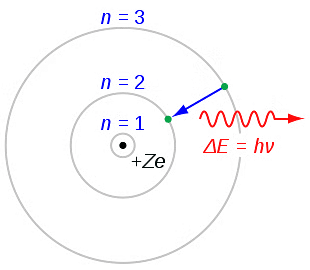

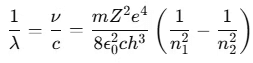

⇒ Ep = ∝ Z2 / n2 - Wavelength of radiation emitted in the radiation from orbit n2 to n1 is given by

- In quantum mechanics, the energies of a system are discrete or quantized. The energy of a particle of mass m is confined to a box of length L can have discrete values of energy given by the relation,

En = n2 h2 / 8mL2 ; n < 1, 2, 3,…

Energy Levels

- The energy of an atom is at its minimum when its electron is in the orbit closest to the nucleus, corresponding to n=1. For higher energy levels (n=2,3, etc.), the absolute value of energy E decreases, making the energy progressively larger in orbits farther from the nucleus.

- The lowest energy state of an atom is called the ground state, with an energy of −13.6 eV. This energy represents the minimum energy required to free the electron from the ground state of the hydrogen atom, known as the ionization energy of hydrogen.

- At room temperature, most hydrogen atoms are in the ground state. When an atom absorbs energy (such as through electron collisions), it can be raised to a higher energy state, known as an excited state.

- In this state, the atom can later return to a lower energy state by emitting a photon with energy equal to the difference between the two energy levels.

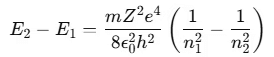

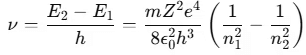

- If an electron in an excited atom moves from a higher energy state n2 to a lower energy state n1, the energy difference is given by:

- According to Bohr’s third postulate, the frequency ν of the emitted photon is:

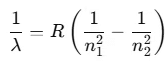

- The wavelength λ of the emitted radiation is given by:

- The term 1/λ is called the wave number, representing the number of waves per unit length.

In this equation, the quantity is a constant called the Rydberg constant R, with a value of 1.097 × 107 m-1.

is a constant called the Rydberg constant R, with a value of 1.097 × 107 m-1.

Thus, the formula becomes:

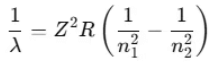

- This is Bohr’s formula for hydrogen and hydrogen-like atoms (such as He+, Li2+, etc.).

For a hydrogen atom (Z = 1):

Example 2. (i) The radius of the innermost electron orbit of a hydrogen atom is 5.3 × 10⁻¹¹ m. Calculate its radius in n = 2 orbit.

(ii) The total energy of an electron in the second excited state of the hydrogen atom is −1.51 eV. Find out its

(a) kinetic energy and

(b) potential energy in this state.

Sol.

(i) Given, Bohr radius, r1 = 5.3 × 10⁻11 m

We know that, rn = n2 × r1

Let r2 be the radius of the orbit for n = 2

r2 = (22) × 5.3 × 10-11

r2 = 2.12 × 10-10 m

(ii) Given, total energy of an electron in second excited state,

E = - 1.51 eV

(a) Kinetic energy of electron is equal to negative of the total energy,

K = -E = -(-1.51) = 1.51 eV

(b) Potential energy of electron is equal to negative of twice its kinetic energy.

U = -2K = -2 × 1.51 = -3.02 eV

Hydrogen Spectrum Series

The hydrogen spectrum displays discrete bright lines against a dark background, known as the hydrogen emission spectrum.

Conversely, when dark lines appear on a bright background, it is referred to as the absorption spectrum. Balmer identified an empirical formula for a part of this spectrum:

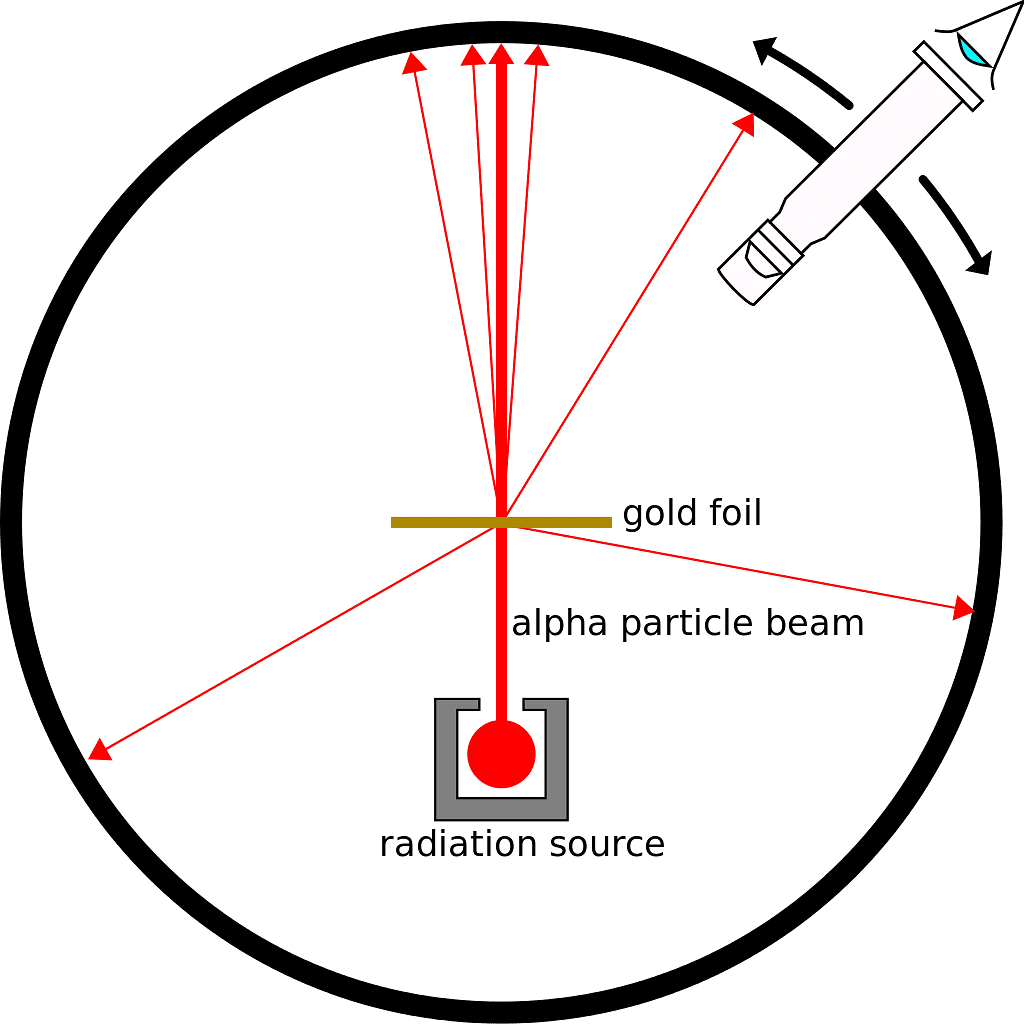

Here, R is the Rydberg constant with a value of 1.097 × 107 m-1. For n = 3, this yields:

1/λ = 1.522 × 106 m-1 ⇒ λ = 656.3 nm

Other hydrogen spectral series were later identified, named after their discoverers. The Balmer series lines appear in the visible range, while other series are in the invisible ultraviolet and infrared regions, such as the Lyman series (ultraviolet) and the Paschen, Brackett, and P fund series (infrared).

Formulas for these series are:

Explanation of the Hydrogen Spectrum

Bohr’s theory helps explain the hydrogen spectral series. If the ionized hydrogen atom state is taken as the zero energy level, the energies of other atomic energy levels are given by:

Here, R is the Rydberg constant, h is Planck's constant, and n is the principal quantum number.

When an atom absorbs energy, its electron moves to a higher energy level, eventually returning to the lowest level by emitting photons. This transition back to the ground state or lower energy levels produces spectral lines.

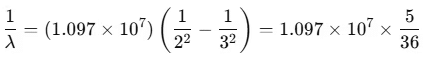

Example 3. In H-atom, a transition takes place from n = 3 to n = 2 orbit. Calculate the wavelength of the emitted photon, will the photon be visible? To which spectral series will this photon belong?

(Take, R = 1.097 × 107 m-1)

Sol. The wavelength of the emitted photon is given by

When the transition takes place from n = 3 to n = 2, then

∴

Since λ falls in the visible (red) part of the spectrum, hence the photon will be visible.

This photon is the first member of the Balmer series.

De Broglie's Comment on Bohr’s Second Postulate

According to de Broglie, a stable (stationary) orbit is one in which the electron's motion is associated with an integer number of de Broglie wavelengths. For an electron orbiting in the n-th circular orbit with radius rn, the total distance covered (circumference) is:

2πrn = nλ

The de Broglie wavelength λ is:

λ = h / (m vn)

where vn is the electron's speed in the n-th orbit. Thus,

2πrn = (nh) / (mvn) ⇒ m vn rn = (nh) / (2π)

This expression confirms that the angular momentum of the electron in a stationary orbit is quantized as an integral multiple of h / (2π), consistent with Bohr’s second postulate.

|

98 videos|332 docs|102 tests

|

FAQs on Atoms - Physics Class 12 - NEET

| 1. What is Thomson's Atomic Model and how does it differ from Rutherford's model? |  |

| 2. What was the significance of Rutherford's experiment in understanding atomic structure? |  |

| 3. How do electron orbits relate to Bohr's Model of the Hydrogen Atom? |  |

| 4. What are energy levels, and how do they affect the hydrogen spectrum series? |  |

| 5. What is Bohr's Theory and its implications for atomic spectra? |  |

where h is Planck’s constant (6.63 x 10−34 J·s). Thus, the angular momentum L of the orbiting electron is quantized and is given by:

where h is Planck’s constant (6.63 x 10−34 J·s). Thus, the angular momentum L of the orbiting electron is quantized and is given by: where n is a positive integer known as the principal quantum number. As the angular momentum of an electron is mvr, for any permitted (stationary) orbit, we have:

where n is a positive integer known as the principal quantum number. As the angular momentum of an electron is mvr, for any permitted (stationary) orbit, we have:

is a constant called the Rydberg constant R, with a value of 1.097 × 107 m-1.

is a constant called the Rydberg constant R, with a value of 1.097 × 107 m-1.