Syntax Definition: Simple Syntax Directed Translation | Compiler Design - Computer Science Engineering (CSE) PDF Download

Syntax Definition

1 Definition of Grammars

2 Derivations

3 Parse Trees

4 Ambiguity

5 Associativity of Operators

6 Precedence of Operators

In this section, we introduce a notation - the "context-free grammar," or "grammar" for short - that is used to specify the syntax of a language. Gram-mars will be used throughout this book to organize compiler front ends.

A grammar naturally describes the hierarchical structure of most program-ming language constructs. For example, an if-else statement in Java can have the form

if ( expression ) statement else statement

That is, an if-else statement is the concatenation of the keyword if, an open-ing parenthesis, an expression, a closing parenthesis, a statement, the keyword else, and another statement. Using the variable expr to denote an expres-sion and the variable stmt to denote a statement, this structuring rule can be expressed as

stmt -> + if ( expr ) stmt else stmt

in which the arrow may be read as "can have the form." Such a rule is called a production. In a production, lexical elements like the keyword if and the paren-theses are called terminals. Variables like expr and stmt represent sequences of terminals and are called nonterminals.

1 Definition of Grammars

A context-free grammar has four components:

1.A set of terminal symbols, sometimes referred to as "tokens." The termi-nals are the elementary symbols of the language defined by the grammar.

2. A set of nonterminals, sometimes called "syntactic variables." Each non-terminal represents a set of strings of terminals, in a manner we shall describe.

3. A set of productions, where each production consists of a nonterminal, called the head or left side of the production, an arrow, and a sequence of terminals and1or nonterminals, called the body or right side of the produc-tion. The intuitive intent of a production is to specify one of the written forms of a construct; if the head nonterminal represents a construct, then the body represents a written form of the construct.

4. A designation of one of the nonterminals as the start symbol.

We specify grammars by listing their productions, with the productions for the start symbol listed first. We assume that digits, signs such as < and <=, and boldface strings such as while are terminals. An italicized name is a nonterminal, and any nonitalicized name or symbol may be assumed to be a terminal.' For notational convenience, productions with the same nonterminal as the head can have their bodies grouped, with the alternative bodies separated by the symbol 1 , which we read as "or."

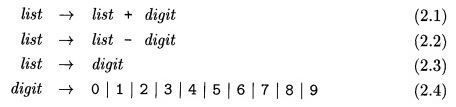

Example 2.1 : Several examples in this chapter use expressions consisting of digits and plus and minus signs; e.g., strings such as 9-5+2, 3-1, or 7. Since a plus or minus sign must appear between two digits, we refer to such expressions as "lists of digits separated by plus or minus signs." The following grammar describes the syntax of these expressions. The productions are:

The bodies of the three productions with nonterminal list as head equivalently can be grouped:

According to our conventions, the terminals of the grammar are the symbols

+ - 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

The nonterminals are the italicized names list and digit, with list being the start symbol because its productions are given first.

We say a production is for a nonterminal if the nonterminal is the head of the production. A string of terminals is a sequence of zero or more terminals. The string of zero terminals, written as E , is called the e m p t y string2

2 Derivations

A grammar derives strings by beginning with the start symbol and repeatedly replacing a nonterminal by the body of a production for that nonterminal. The terminal strings that can be derived from the start symbol form the language defined by the grammar.

Example 2.2 : The language defined by the grammar of Example 2.1 consists of lists of digits separated by plus and minus signs. The ten productions for the nonterminal digit allow it to stand for any of the terminals 0 , 1 , . . . ,9 . From production (2.3), a single digit by itself is a list. Productions (2.1) and (2.2) express the rule that any list followed by a plus or minus sign and then another digit makes up a new list.

Productions (2.1) to (2.4) are all we need to define the desired language. For example, we can deduce that 9-5+2 is a list as follows.

a) 9 is a list by production (2.3), since 9 is a digit.

b) 9-5 is a list by production (2.2), since 9 is a list and 5 is a digit.

c) 9-5+2 is a list by production (2.1), since 9-5 is a list and 2 is a digit.

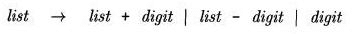

Example 2.3 : A somewhat different sort of list is the list of parameters in a function call. In Java, the parameters are enclosed within parentheses, as in the call max(x, y) of function max with parameters x and y.One nuance of such lists is that an empty list of parameters may be found between the terminals ( and ). We may start to develop a grammar for such sequences with the productions:

Note that the second possible body for optpamm s ("optional parameter list") is t, which stands for the empty string of symbols. That is, optparams can be replaced by the empty string, so a call can consist of a function name followed by the two-terminal string () . Notice that the productions for params are analogous to those for dist in Example 2.1, with comma in place of the arithmetic operator + or -, and param in place of digit. We have not shown the productions for param, since parameters are really arbitrary expressions. Shortly, we shall discuss the appropriate productions for the various language constructs, such as expressions, statements, and so on.

Parsing is the problem of taking a string of terminals and figuring out how to derive it from the start symbol of the grammar, and if it cannot be derived from the start symbol of the grammar, then reporting syntax errors within the string. Parsing is one of the most fundamental problems in all of compiling; the main approaches to parsing are discussed in Chapter 4. In this chapter, for simplicity, we begin with source programs like 9-5+2 in which each character is a terminal; in general, a source program has multicharacter lexemes that are grouped by the lexical analyzer into tokens, whose first components are the terminals processed by the parser.

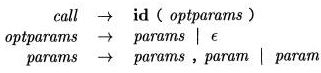

3 Parse Trees

A parse tree pictorially shows how the start symbol of a grammar derives a string in the language. If nonterminal A has a production A -+ X Y Z , then a parse tree may have an interior node labeled A with three children labeled X, Y, and Z, from left to right:

Formally, given a context-free grammar, a parse tree according to the gram-mar is a tree with the following properties:

1. The root is labeled by the start symbol.

2. Each leaf is labeled by a terminal or by e.

3. Each interior node is labeled by a nonterminal.

If A is the nonterminal labeling some interior node and X I , Xz, . . . ,Xn are the labels of the children of that node from left to right, then there must be a production A -> X1X2 . . Xn . Here, X1, X2,. . .,X, each stand for a symbol that is either a terminal or a nonterminal. As a special case, if A -> c is a production, then a node labeled A may have a single child labeled E .

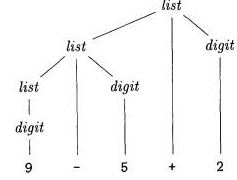

Example 2.4: The derivation of 9-5+2 in Example 2.2 is illustrated by the tree in Fig. 2.5. Each node in the tree is labeled by a grammar symbol. An interior node and its children correspond to a production; the interior node corresponds to the head of the production, the children to the body.

In Fig. 2.5, the root is labeled list, the start symbol of the grammar in Example 2.1. The children of the root are labeled, from left to right, list, +, and digit. Note that

list -> list + digit

is a production in the grammar of Example 2.1. The left child of the root is similar to the root, with a child labeled - instead of +. The three nodes labeled digit each have one child that is labeled by a digit.

From left to right, the leaves of a parse tree form the yield of the tree, which is the string generated or derived from the nonterminal at the root of the parse

tree. In Fig. 2.5, the yield is 9-5+2; for convenience, all the leaves are shown at the bottom level. Henceforth, we shall not necessarily line up the leaves in this way. Any tree imparts a natural left-to-right order to its leaves, based on the idea that if X and Y are two children with the same parent, and X is to the left of Y, then all descendants of X are to the left of descendants of Y.

Another definition of the language generated by a grammar is as the set of strings that can be generated by some parse tree. The process of finding a parse tree for a given string of terminals is called parsing that string.

4 Ambiguity

We have to be careful in talking about the structure of a string according to a grammar. A grammar can have more than one parse tree generating a given string of terminals. Such a grammar is said to be ambiguous. To show that a grammar is ambiguous, all we need to do is find a terminal string that is the yield of more than one parse tree. Since a string with more than one parse tree usually has more than one meaning, we need to design unambiguous grammars for compiling applications, or to use ambiguous grammars with additional rules to resolve the ambiguities.

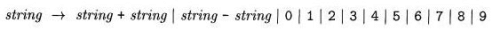

Example 2.5 : Suppose we used a single nonterminal string and did not dis-tinguish between digits and lists, as in Example 2.1. We could have written the grammar

Merging the notion of digit and list into the nonterminal string makes superficial sense, because a singledigit is a special case of a list.

However, Fig. 2.6 shows that an expression like 9-5+2 has more than one parse tree with this grammar. The two trees for 9-5+2 correspond to the two ways of parenthesizing the expression: (9-5) +2 and 9- (5+2) .This second parenthesization gives the expression the unexpected value 2 rather than the customary value 6. The grammar of Example 2.1 does not permit this interpretation.

5. Associativity of Operators

By convention, 9+5+2 is equivalent to (9+5)+2 and 9 - 5 - 2 is equivalent to ( 9 - 5 ) - 2 . When an operand like 5 has operators to its left and right, con-ventions are needed for deciding which operator applies to that operand. We say that the operator + associates to the left, because an operand with plus signs on both sides of it belongs to the operator to its left. In most programming languages the four arithmetic operators, addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division are left-associative.

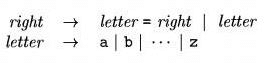

Some common operators such as exponentiation are right-associative. As another example, the assignment operator = in C and its descendants is right-associative; that is, the expression a=b=c is treated in the same way as the expression a =(b=c) .

Strings like a=b=c with a right-associative operator are generated by the following grammar:

The contrast between a parse tree for a left-associative operator like - and a parse tree for a right-associative operator like = is shown by Fig. 2.7. Note that the parse tree for 9 - 5 - 2 grows down towards the left, whereas the parse tree for a-b=c grows down towards the right.

6 Precedence of Operators

Consider the expression 9+5*2. There are two possible interpretations of this expression: (9+5)*2 or 9+(5*2). The associativity rules for + and * apply to occurrences of the same operator, so they do not resolve this ambiguity. Rules defining the relative precedence of operators are needed when more than one kind of operator is present.

We say that * has higher precedence than + if * takes its operands before + does. In ordinary arithmetic, multiplication and division have higher precedence than addition and subtraction. Therefore, 5 is taken by * in both 9+5*2 and 9*5+2; i.e., the expressions are equivalent to 9+(5*2) and (9*5)+2, respectively.

Example 2.6 : A grammar for arithmetic expressions can be constructed from a table showing the associativity and precedence of operators. We start with the four common arithmetic operators and a precedence table, showing the operators in order of increasing precedence. Operators on the same line have the same associativity and precedence:

left-associative: + -

left-associative: * /

We create two nonterminals expr and term for the two levels of precedence, and an extra nonterminal factorfor generating basic units in expressions. The basic units in expressions are presently digits and parenthesized expressions.

factor —> digit | ( expr)

Now consider the binary operators, * and /, that have the highest prece-dence. Since these operators associate to the left, the productions are similar to those for lists that associate to the left.

Generalizing the Expression Grammar of Example 2.6

We can think of a factor as an expression that cannot be "torn apart" by any operator. By "torn apart," we mean that placing an operator next to any factor, on either side, does not cause any piece of the factor, other than the whole, to become an operand of that operator. If the factor is a parenthesized expression, the parentheses protect against such "tearing," while if the factor is a single operand, it cannot be torn apart.

A term (that is not also a factor) is an expression that can be torn apart by operators of the highest precedence: * and /, but not by the lower-precedence operators. An expression (that is not a term or factor) can be torn apart by any operator.

We can generalize this idea to any number n of precedence levels. We need n+1 nonterminals. The first, likefactor in Example 2.6, can never be torn apart. Typically, the production bodies for this nonterminal are only single operands and parenthesized expressions. Then, for each precedence level, there is one nonterminal representing expressions that can be torn apart only by operators at that level or higher. Typically, the productions for this nonterminal have bodies representing uses of the operators at that level, plus one body that is just the nonterminal for the next higher level.

With this grammar, an expression is a list of terms separated by either + or - signs, and a term is a list of factors separated by * or / signs. Notice that any parenthesized expression is a factor, so with parentheses we can develop expressions that have arbitrarily deep nesting (and arbitrarily deep trees). •

Example 2 . 7: Keywords allow us to recognize statements, since most state-ment begin with a keyword or a special character. Exceptions to this rule include assignments and procedure calls. The statements defined by the (am-biguous) grammar in Fig. 2.8 are legal in Java.

In the first production for stmt, the terminal id represents any identifier. The productions for expression are not shown. The assignment statements specified by the first production are legal in Java, although Java treats = as an assignment operator that can appear within an expression. For example, Java allows a = b = c,which this grammar does not.

The nonterminal stmts generates a possibly empty list of statements. The second production for stmtsgenerates the empty list e. The first production generates a possibly empty list of statements followed by a statement.

The placement of semicolons is subtle; they appear at the end of every body that does not end in stmt. This approach prevents the build-up of semicolons after statements such as if- and while-, which end with nested substatements. When the nested substatement is an assignment or a do-while, a semicolon will be generated as part of the substatement. •

Exercise 2 . 2 . 3: Which of the grammars in Exercise 2.2.2 are ambiguous?

Exercise 2 . 2 . 4: Construct unambiguous context-free grammars for each of the following languages. In each case show that your grammar is correct.

Arithmetic expressions in postfix notation.

Left-associative lists of identifiers separated by commas.

Right-associative lists of identifiers separated by commas.

Arithmetic expressions of integers and identifiers with the four binary operators +, -, *, /.

! e) Add unary plus and minus to the arithmetic operators of (d).

Exercise 2 . 2 . 5:

a) Show that all binary strings generated by the following grammar have values divisible by 3. Hint. Use induction on the number of nodes in a parse tree.

num ->• 11 | 1001 | numO | num num

b) Does the grammar generate all binary strings with values divisible by 3?

|

28 videos|86 docs|31 tests

|

FAQs on Syntax Definition: Simple Syntax Directed Translation - Compiler Design - Computer Science Engineering (CSE)

| 1. What is a syntax-directed translator in computer science engineering? |  |

| 2. How does a simple syntax-directed translator work? |  |

| 3. What is the role of semantic actions in a syntax-directed translator? |  |

| 4. What is the difference between a compiler and an interpreter in the context of a syntax-directed translator? |  |

| 5. How does a syntax-directed translator contribute to computer science engineering? |  |