CAT Practice Test - 7 - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - CAT Practice Test - 7

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

WHEN Otto von Bismarck introduced the first pension for workers over 70 in 1889, the life expectancy of a Prussian was 45. In 1908, when Lloyd George bullied through a payment of five shillings a week for poor men who had reached 70, Britons, especially poor ones, were lucky to survive much past 50. By 1935, when America set up its Social Security system, the official pension age was 65—three years beyond the lifespan of the typical American. State-sponsored retirement was designed to be a brief sunset to life, for a few hardy souls.

Now retirement is for everyone, and often as long as whole lives once were. In some European countries the average retirement lasts more than a quarter of a century. In America the official pension age is 66, but the average American retires at 64 and can then expect to live for another 16 years.

Although the idea that “we are all getting older” is a truism, few governments, employers or individuals have yet come to terms with where longer retirement is heading. Whether we like it or not, we are going back to the pre-Bismarckian world, where work had no formal stopping point. That reversion will not happen overnight, but preparations should start now—to ensure that when the inevitable happens it is a change for the better.

It should be for the better because it is being partly driven by a wonderful thing: people are living ever longer. This imminent greying of society is compounded by two other demographic shifts. First, in most rich countries women no longer have enough babies to keep up the numbers; and the huge baby-boom generation, born after the second world war, has begun to retire. In 1950 the OECD countries had seven people aged 20-64 for every one of 65 and over. Now it is four to one—and on course to be two to one by 2050. That will ruin the pay-as-you-go state pension schemes that provide the bulk of retirement income in rich countries.

It is tempting to think that some of the gaps in the rich countries’ labour forces could be filled by immigrants from poorer countries. They already account for much of what little population growth there is in the developed world. But once ageing gets properly under way, the shortfalls will become so large that the flow of immigrants would have to increase to many times what it is now.

Individuals, companies and governments in rich countries will have to adapt. Many employers remain prejudiced against older workers, and not always without reason: performance in manual jobs does drop off in middle age, and older people are often slower on the uptake and less comfortable with new technology. But people past retirement age would not necessarily carry on in the same jobs as before.

Retailers such as Wal-Mart or Britain’s B&Q, and caterers such as McDonald’s, have started hiring pensioners because their customers find them friendlier and more helpful. And skills shortages are already creating opportunities: in the past year or two a dearth of German engineers has caused companies to bring back older workers. Once labour forces start declining, from about 2020, employers will no longer have much choice.

As for the older workers themselves, many of them seem keen enough to carry on beyond retirement. A recent Financial Times/Harris poll showed most Americans, Britons and Italians would work for longer in return for a larger pension. This surely makes sense: as long as the job is not too onerous, many people benefit in mind and body from having something to get them out of the house.

Q. All of the following would not induce some old people from seeking re-employment except

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

WHEN Otto von Bismarck introduced the first pension for workers over 70 in 1889, the life expectancy of a Prussian was 45. In 1908, when Lloyd George bullied through a payment of five shillings a week for poor men who had reached 70, Britons, especially poor ones, were lucky to survive much past 50. By 1935, when America set up its Social Security system, the official pension age was 65—three years beyond the lifespan of the typical American. State-sponsored retirement was designed to be a brief sunset to life, for a few hardy souls.

Now retirement is for everyone, and often as long as whole lives once were. In some European countries the average retirement lasts more than a quarter of a century. In America the official pension age is 66, but the average American retires at 64 and can then expect to live for another 16 years.

Although the idea that “we are all getting older” is a truism, few governments, employers or individuals have yet come to terms with where longer retirement is heading. Whether we like it or not, we are going back to the pre-Bismarckian world, where work had no formal stopping point. That reversion will not happen overnight, but preparations should start now—to ensure that when the inevitable happens it is a change for the better.

It should be for the better because it is being partly driven by a wonderful thing: people are living ever longer. This imminent greying of society is compounded by two other demographic shifts. First, in most rich countries women no longer have enough babies to keep up the numbers; and the huge baby-boom generation, born after the second world war, has begun to retire. In 1950 the OECD countries had seven people aged 20-64 for every one of 65 and over. Now it is four to one—and on course to be two to one by 2050. That will ruin the pay-as-you-go state pension schemes that provide the bulk of retirement income in rich countries.

It is tempting to think that some of the gaps in the rich countries’ labour forces could be filled by immigrants from poorer countries. They already account for much of what little population growth there is in the developed world. But once ageing gets properly under way, the shortfalls will become so large that the flow of immigrants would have to increase to many times what it is now.

Individuals, companies and governments in rich countries will have to adapt. Many employers remain prejudiced against older workers, and not always without reason: performance in manual jobs does drop off in middle age, and older people are often slower on the uptake and less comfortable with new technology. But people past retirement age would not necessarily carry on in the same jobs as before.

Retailers such as Wal-Mart or Britain’s B&Q, and caterers such as McDonald’s, have started hiring pensioners because their customers find them friendlier and more helpful. And skills shortages are already creating opportunities: in the past year or two a dearth of German engineers has caused companies to bring back older workers. Once labour forces start declining, from about 2020, employers will no longer have much choice.

As for the older workers themselves, many of them seem keen enough to carry on beyond retirement. A recent Financial Times/Harris poll showed most Americans, Britons and Italians would work for longer in return for a larger pension. This surely makes sense: as long as the job is not too onerous, many people benefit in mind and body from having something to get them out of the house.

Q. All of the following can be inferred from the passage except

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

WHEN Otto von Bismarck introduced the first pension for workers over 70 in 1889, the life expectancy of a Prussian was 45. In 1908, when Lloyd George bullied through a payment of five shillings a week for poor men who had reached 70, Britons, especially poor ones, were lucky to survive much past 50. By 1935, when America set up its Social Security system, the official pension age was 65—three years beyond the lifespan of the typical American. State-sponsored retirement was designed to be a brief sunset to life, for a few hardy souls.

Now retirement is for everyone, and often as long as whole lives once were. In some European countries the average retirement lasts more than a quarter of a century. In America the official pension age is 66, but the average American retires at 64 and can then expect to live for another 16 years.

Although the idea that “we are all getting older” is a truism, few governments, employers or individuals have yet come to terms with where longer retirement is heading. Whether we like it or not, we are going back to the pre-Bismarckian world, where work had no formal stopping point. That reversion will not happen overnight, but preparations should start now—to ensure that when the inevitable happens it is a change for the better.

It should be for the better because it is being partly driven by a wonderful thing: people are living ever longer. This imminent greying of society is compounded by two other demographic shifts. First, in most rich countries women no longer have enough babies to keep up the numbers; and the huge baby-boom generation, born after the second world war, has begun to retire. In 1950 the OECD countries had seven people aged 20-64 for every one of 65 and over. Now it is four to one—and on course to be two to one by 2050. That will ruin the pay-as-you-go state pension schemes that provide the bulk of retirement income in rich countries.

It is tempting to think that some of the gaps in the rich countries’ labour forces could be filled by immigrants from poorer countries. They already account for much of what little population growth there is in the developed world. But once ageing gets properly under way, the shortfalls will become so large that the flow of immigrants would have to increase to many times what it is now.

Individuals, companies and governments in rich countries will have to adapt. Many employers remain prejudiced against older workers, and not always without reason: performance in manual jobs does drop off in middle age, and older people are often slower on the uptake and less comfortable with new technology. But people past retirement age would not necessarily carry on in the same jobs as before.

Retailers such as Wal-Mart or Britain’s B&Q, and caterers such as McDonald’s, have started hiring pensioners because their customers find them friendlier and more helpful. And skills shortages are already creating opportunities: in the past year or two a dearth of German engineers has caused companies to bring back older workers. Once labour forces start declining, from about 2020, employers will no longer have much choice.

As for the older workers themselves, many of them seem keen enough to carry on beyond retirement. A recent Financial Times/Harris poll showed most Americans, Britons and Italians would work for longer in return for a larger pension. This surely makes sense: as long as the job is not too onerous, many people benefit in mind and body from having something to get them out of the house.

Q. According to the passage all of the following are untrue, except

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Until I was 35 years old I thought talking about the weather was for losers. A waste of time, insulting even. No one can do anything about the weather anyway. I believed that any comment that does not offer new insight or otherwise advance the cause of humanity is just so much hot air. I might make an exception for intimate friends, but I sure did not want that kind of intimacy with the man on the street, or the one in my office.

Then something happened. Alone for the first time in a long time, living in challenging circumstances, experiencing a cold winter in New England, I noticed the weather. It affected me deeply and directly, every single day. Slowly it dawned on me that the weather affected everyone else, too. Maybe talking about it wasn't totally vacuous after all.

I started with the cashier at a gas station. I figured I'd never see her again, so it was pretty safe. She has no clue that I was a smart person with a lot of potential. Years of cynicism made me almost laugh as I said. 'Sure got a lot of snow this year so far. Yep, was her reply. Then she said, I could barely get my car out of the lot, be careful driving. Talking about the weather was easy, even effortless. An entree to at least one person on the planet who apparently cared about me, at least enough to share her small challenge and want me safe on the road.

Next time I tried it at work. It turned out to be even more effective with people I already knew. Talking about the weather acted as a little bridge, sometimes to further conversation and sometimes just to the mutual acknowledgment of shared experience. Whether it was rainy or snowy or sunny or damp for everyone, each had their own relationship with the weather. They might be achy, delighted, burdened, grumpy, relieved or simply cold or hot. Like anything of personal importance, most were grateful for the opportunity to talk about it.

Then something else happened. As talking about the weather became more natural, I found myself talking about a whole lot more. I found out about people's families, their frustrations at work, their plans and aspirations. Plus, I found out that the weather is not the same for everyone! And it's only one of many factors dependent on location that you'll never know about without engaging in casual conversation.

For a businessperson, there may be no better way to make a connection, continue a thread, or open a deeper dialogue. Honoring the simple reality of another person's experience is an instant link to the bigger world outside one's self. It's the seed of empathy, and it's free.

Q. As used in the third paragraph, the word entree most likely stands for -

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Until I was 35 years old I thought talking about the weather was for losers. A waste of time, insulting even. No one can do anything about the weather anyway. I believed that any comment that does not offer new insight or otherwise advance the cause of humanity is just so much hot air. I might make an exception for intimate friends, but I sure did not want that kind of intimacy with the man on the street, or the one in my office.

Then something happened. Alone for the first time in a long time, living in challenging circumstances, experiencing a cold winter in New England, I noticed the weather. It affected me deeply and directly, every single day. Slowly it dawned on me that the weather affected everyone else, too. Maybe talking about it wasn't totally vacuous after all.

I started with the cashier at a gas station. I figured I'd never see her again, so it was pretty safe. She has no clue that I was a smart person with a lot of potential. Years of cynicism made me almost laugh as I said. 'Sure got a lot of snow this year so far. Yep, was her reply. Then she said, I could barely get my car out of the lot, be careful driving. Talking about the weather was easy, even effortless. An entree to at least one person on the planet who apparently cared about me, at least enough to share her small challenge and want me safe on the road.

Next time I tried it at work. It turned out to be even more effective with people I already knew. Talking about the weather acted as a little bridge, sometimes to further conversation and sometimes just to the mutual acknowledgment of shared experience. Whether it was rainy or snowy or sunny or damp for everyone, each had their own relationship with the weather. They might be achy, delighted, burdened, grumpy, relieved or simply cold or hot. Like anything of personal importance, most were grateful for the opportunity to talk about it.

Then something else happened. As talking about the weather became more natural, I found myself talking about a whole lot more. I found out about people's families, their frustrations at work, their plans and aspirations. Plus, I found out that the weather is not the same for everyone! And it's only one of many factors dependent on location that you'll never know about without engaging in casual conversation.

For a businessperson, there may be no better way to make a connection, continue a thread, or open a deeper dialogue. Honoring the simple reality of another person's experience is an instant link to the bigger world outside one's self. It's the seed of empathy, and it's free.

Q. What is the main theme of the passage?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Until I was 35 years old I thought talking about the weather was for losers. A waste of time, insulting even. No one can do anything about the weather anyway. I believed that any comment that does not offer new insight or otherwise advance the cause of humanity is just so much hot air. I might make an exception for intimate friends, but I sure did not want that kind of intimacy with the man on the street, or the one in my office.

Then something happened. Alone for the first time in a long time, living in challenging circumstances, experiencing a cold winter in New England, I noticed the weather. It affected me deeply and directly, every single day. Slowly it dawned on me that the weather affected everyone else, too. Maybe talking about it wasn't totally vacuous after all.

I started with the cashier at a gas station. I figured I'd never see her again, so it was pretty safe. She has no clue that I was a smart person with a lot of potential. Years of cynicism made me almost laugh as I said. 'Sure got a lot of snow this year so far. Yep, was her reply. Then she said, I could barely get my car out of the lot, be careful driving. Talking about the weather was easy, even effortless. An entree to at least one person on the planet who apparently cared about me, at least enough to share her small challenge and want me safe on the road.

Next time I tried it at work. It turned out to be even more effective with people I already knew. Talking about the weather acted as a little bridge, sometimes to further conversation and sometimes just to the mutual acknowledgment of shared experience. Whether it was rainy or snowy or sunny or damp for everyone, each had their own relationship with the weather. They might be achy, delighted, burdened, grumpy, relieved or simply cold or hot. Like anything of personal importance, most were grateful for the opportunity to talk about it.

Then something else happened. As talking about the weather became more natural, I found myself talking about a whole lot more. I found out about people's families, their frustrations at work, their plans and aspirations. Plus, I found out that the weather is not the same for everyone! And it's only one of many factors dependent on location that you'll never know about without engaging in casual conversation.

For a businessperson, there may be no better way to make a connection, continue a thread, or open a deeper dialogue. Honoring the simple reality of another person's experience is an instant link to the bigger world outside one's self. It's the seed of empathy, and it's free.

Q. In the fourth paragraph, what is meant by the phrase 'each had their own relationship with the weather'?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

I don’t know how to write. Which is unfortunate, as I do it for a living. Mind you, I don’t know how to live either. Writers are asked, particularly when we’ve got a book coming out, to write about writing. To give interviews and explain how we did this thing that we appear to have done. We even teach, as I have recently, students who want to know how to approach the peculiar occupation of fiction writing. I tell them at the beginning—I’ve got nothing for you. I don’t know. Don’t look at me.

I’ve written six books now, but instead of making it easier, it has complicated matters to the point of absurdity. I have no idea what I’m doing. All the decisions I appear to have made—about plots and characters and where to start and when to stop—are not decisions at all. They are compromises. A book is whittled down from hope, and when I start to cut my fingers I push it away from me to see what others make of it. And I wait in terror for the judgements of those others—judgements that seem, whether positive or negative, unjust, because they are about something that I didn’t really do. They are about something that happened to me. It’s a little like crawling from a car crash to be greeted by a panel of strangers holding up score cards.

Something, obviously, is going on. I manage, every few years, to generate a book. And of course, there are things that I know. I know how to wait until the last minute before putting anything on paper. I mean the last minute before the thought leaves me forever. I know how to leave out anything that looks to me—after a while—forced, deliberate, or fake. I know that I need to put myself in the story. I don’t mean literally. I mean emotionally. I need to care about what I’m writing—whether about the characters, or about what they’re getting up to, or about the way they feel or experience their world. I know that my job is to create a perspective. And to impose it on the reader. And I know that in order to do that with any success at all I must in some mysterious way risk everything. If I don’t break my own heart in the writing of a book then I know I’ve done it wrong. I’m not entirely sure what that means. But I know what it feels like.

I do no research. Given that I’ve just written a book that revolves around two London Met police detectives, this might seem a little foolhardy. I have no real idea what detectives do with their days. So I made some guesses. I suppose that they must investigate things. I tried to imagine what that might be like. I’ve seen the same films and TV shows that you have. I’ve read the same sorts of cheap thrillers. And I know that everything is fiction. Absolutely everything. Research is its own slow fiction, a process of reassurance for the author. I don’t want reassurance. I like writing out of confusion, panic, a sense of everything being perilously close to collapse. So I try to embrace the fiction of all things.

And I mean that—everything is fiction. When you tell yourself the story of your life, the story of your day, you edit and rewrite and weave a narrative out of a collection of random experiences and events. Your conversations are fiction. Your friends and loved ones—they are characters you have created. And your arguments with them are like meetings with an editor—please, they beseech you, you beseech them, rewrite me. You have a perception of the way things are, and you impose it on your memory, and in this way you think, in the same way that I think, that you are living something that is describable. When of course, what we actually live, what we actually experience—with our senses and our nerves—is a vast, absurd, beautiful, ridiculous chaos.

So I love hearing from people who have no time for fiction. Who read only biographies and popular science. I love hearing about the death of the novel. I love getting lectures about the triviality of fiction, the triviality of making things up. As if that wasn’t what all of us do, all day long, all life long. Fiction gives us everything. It gives us our memories, our understanding, our insight, our lives. We use it to invent ourselves and others. We use it to feel change and sadness and hope and love and to tell each other about ourselves. And we all, it turns out, know how to do it.

Q. A central idea that the author of the passage subscribes to is:

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

I don’t know how to write. Which is unfortunate, as I do it for a living. Mind you, I don’t know how to live either. Writers are asked, particularly when we’ve got a book coming out, to write about writing. To give interviews and explain how we did this thing that we appear to have done. We even teach, as I have recently, students who want to know how to approach the peculiar occupation of fiction writing. I tell them at the beginning—I’ve got nothing for you. I don’t know. Don’t look at me.

I’ve written six books now, but instead of making it easier, it has complicated matters to the point of absurdity. I have no idea what I’m doing. All the decisions I appear to have made—about plots and characters and where to start and when to stop—are not decisions at all. They are compromises. A book is whittled down from hope, and when I start to cut my fingers I push it away from me to see what others make of it. And I wait in terror for the judgements of those others—judgements that seem, whether positive or negative, unjust, because they are about something that I didn’t really do. They are about something that happened to me. It’s a little like crawling from a car crash to be greeted by a panel of strangers holding up score cards.

Something, obviously, is going on. I manage, every few years, to generate a book. And of course, there are things that I know. I know how to wait until the last minute before putting anything on paper. I mean the last minute before the thought leaves me forever. I know how to leave out anything that looks to me—after a while—forced, deliberate, or fake. I know that I need to put myself in the story. I don’t mean literally. I mean emotionally. I need to care about what I’m writing—whether about the characters, or about what they’re getting up to, or about the way they feel or experience their world. I know that my job is to create a perspective. And to impose it on the reader. And I know that in order to do that with any success at all I must in some mysterious way risk everything. If I don’t break my own heart in the writing of a book then I know I’ve done it wrong. I’m not entirely sure what that means. But I know what it feels like.

I do no research. Given that I’ve just written a book that revolves around two London Met police detectives, this might seem a little foolhardy. I have no real idea what detectives do with their days. So I made some guesses. I suppose that they must investigate things. I tried to imagine what that might be like. I’ve seen the same films and TV shows that you have. I’ve read the same sorts of cheap thrillers. And I know that everything is fiction. Absolutely everything. Research is its own slow fiction, a process of reassurance for the author. I don’t want reassurance. I like writing out of confusion, panic, a sense of everything being perilously close to collapse. So I try to embrace the fiction of all things.

And I mean that—everything is fiction. When you tell yourself the story of your life, the story of your day, you edit and rewrite and weave a narrative out of a collection of random experiences and events. Your conversations are fiction. Your friends and loved ones—they are characters you have created. And your arguments with them are like meetings with an editor—please, they beseech you, you beseech them, rewrite me. You have a perception of the way things are, and you impose it on your memory, and in this way you think, in the same way that I think, that you are living something that is describable. When of course, what we actually live, what we actually experience—with our senses and our nerves—is a vast, absurd, beautiful, ridiculous chaos.

So I love hearing from people who have no time for fiction. Who read only biographies and popular science. I love hearing about the death of the novel. I love getting lectures about the triviality of fiction, the triviality of making things up. As if that wasn’t what all of us do, all day long, all life long. Fiction gives us everything. It gives us our memories, our understanding, our insight, our lives. We use it to invent ourselves and others. We use it to feel change and sadness and hope and love and to tell each other about ourselves. And we all, it turns out, know how to do it.

Q. It can be inferred from the passage that:

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

I don’t know how to write. Which is unfortunate, as I do it for a living. Mind you, I don’t know how to live either. Writers are asked, particularly when we’ve got a book coming out, to write about writing. To give interviews and explain how we did this thing that we appear to have done. We even teach, as I have recently, students who want to know how to approach the peculiar occupation of fiction writing. I tell them at the beginning—I’ve got nothing for you. I don’t know. Don’t look at me.

I’ve written six books now, but instead of making it easier, it has complicated matters to the point of absurdity. I have no idea what I’m doing. All the decisions I appear to have made—about plots and characters and where to start and when to stop—are not decisions at all. They are compromises. A book is whittled down from hope, and when I start to cut my fingers I push it away from me to see what others make of it. And I wait in terror for the judgements of those others—judgements that seem, whether positive or negative, unjust, because they are about something that I didn’t really do. They are about something that happened to me. It’s a little like crawling from a car crash to be greeted by a panel of strangers holding up score cards.

Something, obviously, is going on. I manage, every few years, to generate a book. And of course, there are things that I know. I know how to wait until the last minute before putting anything on paper. I mean the last minute before the thought leaves me forever. I know how to leave out anything that looks to me—after a while—forced, deliberate, or fake. I know that I need to put myself in the story. I don’t mean literally. I mean emotionally. I need to care about what I’m writing—whether about the characters, or about what they’re getting up to, or about the way they feel or experience their world. I know that my job is to create a perspective. And to impose it on the reader. And I know that in order to do that with any success at all I must in some mysterious way risk everything. If I don’t break my own heart in the writing of a book then I know I’ve done it wrong. I’m not entirely sure what that means. But I know what it feels like.

I do no research. Given that I’ve just written a book that revolves around two London Met police detectives, this might seem a little foolhardy. I have no real idea what detectives do with their days. So I made some guesses. I suppose that they must investigate things. I tried to imagine what that might be like. I’ve seen the same films and TV shows that you have. I’ve read the same sorts of cheap thrillers. And I know that everything is fiction. Absolutely everything. Research is its own slow fiction, a process of reassurance for the author. I don’t want reassurance. I like writing out of confusion, panic, a sense of everything being perilously close to collapse. So I try to embrace the fiction of all things.

And I mean that—everything is fiction. When you tell yourself the story of your life, the story of your day, you edit and rewrite and weave a narrative out of a collection of random experiences and events. Your conversations are fiction. Your friends and loved ones—they are characters you have created. And your arguments with them are like meetings with an editor—please, they beseech you, you beseech them, rewrite me. You have a perception of the way things are, and you impose it on your memory, and in this way you think, in the same way that I think, that you are living something that is describable. When of course, what we actually live, what we actually experience—with our senses and our nerves—is a vast, absurd, beautiful, ridiculous chaos.

So I love hearing from people who have no time for fiction. Who read only biographies and popular science. I love hearing about the death of the novel. I love getting lectures about the triviality of fiction, the triviality of making things up. As if that wasn’t what all of us do, all day long, all life long. Fiction gives us everything. It gives us our memories, our understanding, our insight, our lives. We use it to invent ourselves and others. We use it to feel change and sadness and hope and love and to tell each other about ourselves. And we all, it turns out, know how to do it.

Q. According to the author of the passage, when others judge his work, those judgements can be said to be:

i. unfair

ii. undeserved

iii. biased

iv. influenced

v. shabby

How many of the above words are valid in the given context of the passage?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

A new source of methane – a greenhouse gas many times more powerful than carbon dioxide – has been identified by scientists flying over areas in the Arctic where the sea ice has melted.

The researchers found significant amounts of methane being released from the ocean into the atmosphere through cracks in the melting sea ice. They said the quantities could be large enough to affect the global climate. Previous observations have pointed to large methane plumes being released from the seabed in the relatively shallow sea off the northern coast of Siberia but the latest findings were made far away from land in the deep, open ocean where the surface is usually capped by ice.

Eric Kort of Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said that he and his colleagues were surprised to see methane levels rise so dramatically each time their research aircraft flew over cracks in the sea ice.

"When we flew over completely solid sea ice, we didn't see anything in terms of methane. But when we flew over areas were the sea ice had melted, or where there were cracks in the ice, we saw the methane levels increase," Dr Kort said. "We were surprised to see these enhanced methane levels at these high latitudes. Our observations really point to the ocean surface as the source, which was not what we had expected," he said.

"Other scientists had seen high concentrations of methane in the sea surface but nobody had expected to see it being released into the atmosphere in this way," he added.

Methane is about 70 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide when it comes to trapping heat. However, because methane is broken down more quickly in the atmosphere, scientists calculate that it is 20 times more powerful over a 100-year cycle. The latest methane measurements were made from the American HIPPO research programme where a research aircraft loaded with scientific instruments flies for long distances at varying altitudes, measuring and recording gas levels at different heights.

The study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, covered several flights into the Arctic at different times of the year. They covered an area about 950 miles north of the coast of Alaska and about 350 miles south of the North Pole. Dr Kort said that the levels of methane coming off this region were about the same as the quantities measured by other scientists monitoring methane levels above the shallow sea of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf.

"We suggest that the surface waters of the Arctic Ocean represent a potentially important source of methane, which could prove sensitive to changes in sea ice cover," the researchers write. "The association with sea ice makes this methane source likely to be sensitive to changing Arctic ice cover and dynamics, providing an unrecognised feedback process in the global atmosphere-climate system," they say.

Climate scientists are concerned that rising temperatures in the Arctic could trigger climate-feedbacks, where melting ice results in the release of methane which in turn results in a further increase in temperatures.

Q. Methane is

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

A new source of methane – a greenhouse gas many times more powerful than carbon dioxide – has been identified by scientists flying over areas in the Arctic where the sea ice has melted.

The researchers found significant amounts of methane being released from the ocean into the atmosphere through cracks in the melting sea ice. They said the quantities could be large enough to affect the global climate. Previous observations have pointed to large methane plumes being released from the seabed in the relatively shallow sea off the northern coast of Siberia but the latest findings were made far away from land in the deep, open ocean where the surface is usually capped by ice.

Eric Kort of Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said that he and his colleagues were surprised to see methane levels rise so dramatically each time their research aircraft flew over cracks in the sea ice.

"When we flew over completely solid sea ice, we didn't see anything in terms of methane. But when we flew over areas were the sea ice had melted, or where there were cracks in the ice, we saw the methane levels increase," Dr Kort said. "We were surprised to see these enhanced methane levels at these high latitudes. Our observations really point to the ocean surface as the source, which was not what we had expected," he said.

"Other scientists had seen high concentrations of methane in the sea surface but nobody had expected to see it being released into the atmosphere in this way," he added.

Methane is about 70 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide when it comes to trapping heat. However, because methane is broken down more quickly in the atmosphere, scientists calculate that it is 20 times more powerful over a 100-year cycle. The latest methane measurements were made from the American HIPPO research programme where a research aircraft loaded with scientific instruments flies for long distances at varying altitudes, measuring and recording gas levels at different heights.

The study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, covered several flights into the Arctic at different times of the year. They covered an area about 950 miles north of the coast of Alaska and about 350 miles south of the North Pole. Dr Kort said that the levels of methane coming off this region were about the same as the quantities measured by other scientists monitoring methane levels above the shallow sea of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf.

"We suggest that the surface waters of the Arctic Ocean represent a potentially important source of methane, which could prove sensitive to changes in sea ice cover," the researchers write. "The association with sea ice makes this methane source likely to be sensitive to changing Arctic ice cover and dynamics, providing an unrecognised feedback process in the global atmosphere-climate system," they say.

Climate scientists are concerned that rising temperatures in the Arctic could trigger climate-feedbacks, where melting ice results in the release of methane which in turn results in a further increase in temperatures.

Q. What is the tone of the passage?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

A new source of methane – a greenhouse gas many times more powerful than carbon dioxide – has been identified by scientists flying over areas in the Arctic where the sea ice has melted.

The researchers found significant amounts of methane being released from the ocean into the atmosphere through cracks in the melting sea ice. They said the quantities could be large enough to affect the global climate. Previous observations have pointed to large methane plumes being released from the seabed in the relatively shallow sea off the northern coast of Siberia but the latest findings were made far away from land in the deep, open ocean where the surface is usually capped by ice.

Eric Kort of Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said that he and his colleagues were surprised to see methane levels rise so dramatically each time their research aircraft flew over cracks in the sea ice.

"When we flew over completely solid sea ice, we didn't see anything in terms of methane. But when we flew over areas were the sea ice had melted, or where there were cracks in the ice, we saw the methane levels increase," Dr Kort said. "We were surprised to see these enhanced methane levels at these high latitudes. Our observations really point to the ocean surface as the source, which was not what we had expected," he said.

"Other scientists had seen high concentrations of methane in the sea surface but nobody had expected to see it being released into the atmosphere in this way," he added.

Methane is about 70 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide when it comes to trapping heat. However, because methane is broken down more quickly in the atmosphere, scientists calculate that it is 20 times more powerful over a 100-year cycle. The latest methane measurements were made from the American HIPPO research programme where a research aircraft loaded with scientific instruments flies for long distances at varying altitudes, measuring and recording gas levels at different heights.

The study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, covered several flights into the Arctic at different times of the year. They covered an area about 950 miles north of the coast of Alaska and about 350 miles south of the North Pole. Dr Kort said that the levels of methane coming off this region were about the same as the quantities measured by other scientists monitoring methane levels above the shallow sea of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf.

"We suggest that the surface waters of the Arctic Ocean represent a potentially important source of methane, which could prove sensitive to changes in sea ice cover," the researchers write. "The association with sea ice makes this methane source likely to be sensitive to changing Arctic ice cover and dynamics, providing an unrecognised feedback process in the global atmosphere-climate system," they say.

Climate scientists are concerned that rising temperatures in the Arctic could trigger climate-feedbacks, where melting ice results in the release of methane which in turn results in a further increase in temperatures.

Q. What pertinent question would you ask the scientist after reading the passage?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

The present day view of alcoholism as a physical disease was not a scientific discovery; it is a medical thesis that has developed only slowly over the past 200 years and amidst considerable controversy. Historically the moral prospective of the Judeo-Christian tradition has been that excessive use of alcohol is wilful act, one that leads to intoxication and other sinful behaviour; but in the early nineteenth century, Benjamin Rush, a founder of American psychiatry, proposed that “The habit of drunkenness is a disease of the will.” By the late nineteenth century, physicians generally viewed the habitual use of drugs such as opiates tobacco and coffee as a generic disorder stemming from biological vulnerability, either inherited or acquired.

Prohibition represented a triumph of the older morality over a modern medical concept. Where physicians who championed the disease concept of alcoholism emphasized the need for treatment, the Temperance Movement stressed that alcohol itself was the cause of drunkenness and advocated its control and eventually its prohibition. Scientific interest in alcoholism, dampened by Prohibition, revived toward the middle of the twentieth century, not because of any new scientific findings but because of humanitarian efforts to shift the focus from blame and punishment, to treatment and concern.

The early 1960s witnessed a growing acceptance of the notion that, in certain “vulnerable” people, alcohol use leads to physical addiction –a true disease. Central to this concept of alcoholism as a disease were the twin notions of substance tolerance and physical dependence, both physical phenomena. Substance tolerance occurs when increased doses of a drug are required to produce effects previously attained at lower dosages; physical dependence refers to the occurrence of withdrawal symptoms, such as seizures, following cessation of a drinking bout. In 1972, the National Council on Alcoholism outlined criteria for diagnosing alcoholism. These criteria emphasized alcohol tolerance and treated alcoholism as an independent disorder, not merely a manifestation of a more general and underlying personality disorder.

In 1977, A World Health Organisation report challenged this disease model by pointing out that not everyone who develops alcohol-related problems exhibits true alcohol dependence. This important distinction between dependence and other drug-related problems that do not involve dependence was not immediately accepted by the American Psychiatric Association. The early drafts of the 1980 edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders described a dependence syndrome for alcohol and other drugs in which tolerance and dependence were important, but not essential, criteria for diagnosis, but at the last moment, the inertia of history prevailed, and tolerance and dependence were both included not as necessary to diagnose dependence but as sufficient indicators in and of themselves.

It was not until 1993 that the American psychiatric Association modified this position. In the fourth edition of the Manual, tolerance and withdrawal symptoms are the first two of seven criteria listed for diagnosing alcohol and other drug dependence, but the clinician is not required to find whether either is present or in what degree in order to make the diagnosis.

Despite the consensus among health professionals, we should not forget that the moral prospective on alcoholism is still very much alive. It perhaps does not surprise us that the Revered J.E. Todd wrote an essay entitled “Drunkenness a Vice, Not a Disease” in 1882, but we should be concerned that the book Heavy Drinking: The Myth of Alcoholism as a Disease was published in 1988. Even as late as the mid – 1970s, sociologists were reporting that the term “alcoholic” was commonly used in the United States as synonym for “drunkard,” rather than as a designation for someone with an illness or a disorder. Apparently, in the mind of non-professionals, the contradictory notions of alcoholism as a disease and alcoholism as a moral weakness can coexist quite comfortably.

Q. The author would most likely agree with which of the following statements?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

The present day view of alcoholism as a physical disease was not a scientific discovery; it is a medical thesis that has developed only slowly over the past 200 years and amidst considerable controversy. Historically the moral prospective of the Judeo-Christian tradition has been that excessive use of alcohol is wilful act, one that leads to intoxication and other sinful behaviour; but in the early nineteenth century, Benjamin Rush, a founder of American psychiatry, proposed that “The habit of drunkenness is a disease of the will.” By the late nineteenth century, physicians generally viewed the habitual use of drugs such as opiates tobacco and coffee as a generic disorder stemming from biological vulnerability, either inherited or acquired.

Prohibition represented a triumph of the older morality over a modern medical concept. Where physicians who championed the disease concept of alcoholism emphasized the need for treatment, the Temperance Movement stressed that alcohol itself was the cause of drunkenness and advocated its control and eventually its prohibition. Scientific interest in alcoholism, dampened by Prohibition, revived toward the middle of the twentieth century, not because of any new scientific findings but because of humanitarian efforts to shift the focus from blame and punishment, to treatment and concern.

The early 1960s witnessed a growing acceptance of the notion that, in certain “vulnerable” people, alcohol use leads to physical addiction –a true disease. Central to this concept of alcoholism as a disease were the twin notions of substance tolerance and physical dependence, both physical phenomena. Substance tolerance occurs when increased doses of a drug are required to produce effects previously attained at lower dosages; physical dependence refers to the occurrence of withdrawal symptoms, such as seizures, following cessation of a drinking bout. In 1972, the National Council on Alcoholism outlined criteria for diagnosing alcoholism. These criteria emphasized alcohol tolerance and treated alcoholism as an independent disorder, not merely a manifestation of a more general and underlying personality disorder.

In 1977, A World Health Organisation report challenged this disease model by pointing out that not everyone who develops alcohol-related problems exhibits true alcohol dependence. This important distinction between dependence and other drug-related problems that do not involve dependence was not immediately accepted by the American Psychiatric Association. The early drafts of the 1980 edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders described a dependence syndrome for alcohol and other drugs in which tolerance and dependence were important, but not essential, criteria for diagnosis, but at the last moment, the inertia of history prevailed, and tolerance and dependence were both included not as necessary to diagnose dependence but as sufficient indicators in and of themselves.

It was not until 1993 that the American psychiatric Association modified this position. In the fourth edition of the Manual, tolerance and withdrawal symptoms are the first two of seven criteria listed for diagnosing alcohol and other drug dependence, but the clinician is not required to find whether either is present or in what degree in order to make the diagnosis.

Despite the consensus among health professionals, we should not forget that the moral prospective on alcoholism is still very much alive. It perhaps does not surprise us that the Revered J.E. Todd wrote an essay entitled “Drunkenness a Vice, Not a Disease” in 1882, but we should be concerned that the book Heavy Drinking: The Myth of Alcoholism as a Disease was published in 1988. Even as late as the mid – 1970s, sociologists were reporting that the term “alcoholic” was commonly used in the United States as synonym for “drunkard,” rather than as a designation for someone with an illness or a disorder. Apparently, in the mind of non-professionals, the contradictory notions of alcoholism as a disease and alcoholism as a moral weakness can coexist quite comfortably.

Q. Which of the following is not in accordance with the passage?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

The present day view of alcoholism as a physical disease was not a scientific discovery; it is a medical thesis that has developed only slowly over the past 200 years and amidst considerable controversy. Historically the moral prospective of the Judeo-Christian tradition has been that excessive use of alcohol is wilful act, one that leads to intoxication and other sinful behaviour; but in the early nineteenth century, Benjamin Rush, a founder of American psychiatry, proposed that “The habit of drunkenness is a disease of the will.” By the late nineteenth century, physicians generally viewed the habitual use of drugs such as opiates tobacco and coffee as a generic disorder stemming from biological vulnerability, either inherited or acquired.

Prohibition represented a triumph of the older morality over a modern medical concept. Where physicians who championed the disease concept of alcoholism emphasized the need for treatment, the Temperance Movement stressed that alcohol itself was the cause of drunkenness and advocated its control and eventually its prohibition. Scientific interest in alcoholism, dampened by Prohibition, revived toward the middle of the twentieth century, not because of any new scientific findings but because of humanitarian efforts to shift the focus from blame and punishment, to treatment and concern.

The early 1960s witnessed a growing acceptance of the notion that, in certain “vulnerable” people, alcohol use leads to physical addiction –a true disease. Central to this concept of alcoholism as a disease were the twin notions of substance tolerance and physical dependence, both physical phenomena. Substance tolerance occurs when increased doses of a drug are required to produce effects previously attained at lower dosages; physical dependence refers to the occurrence of withdrawal symptoms, such as seizures, following cessation of a drinking bout. In 1972, the National Council on Alcoholism outlined criteria for diagnosing alcoholism. These criteria emphasized alcohol tolerance and treated alcoholism as an independent disorder, not merely a manifestation of a more general and underlying personality disorder.

In 1977, A World Health Organisation report challenged this disease model by pointing out that not everyone who develops alcohol-related problems exhibits true alcohol dependence. This important distinction between dependence and other drug-related problems that do not involve dependence was not immediately accepted by the American Psychiatric Association. The early drafts of the 1980 edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders described a dependence syndrome for alcohol and other drugs in which tolerance and dependence were important, but not essential, criteria for diagnosis, but at the last moment, the inertia of history prevailed, and tolerance and dependence were both included not as necessary to diagnose dependence but as sufficient indicators in and of themselves.

It was not until 1993 that the American psychiatric Association modified this position. In the fourth edition of the Manual, tolerance and withdrawal symptoms are the first two of seven criteria listed for diagnosing alcohol and other drug dependence, but the clinician is not required to find whether either is present or in what degree in order to make the diagnosis.

Despite the consensus among health professionals, we should not forget that the moral prospective on alcoholism is still very much alive. It perhaps does not surprise us that the Revered J.E. Todd wrote an essay entitled “Drunkenness a Vice, Not a Disease” in 1882, but we should be concerned that the book Heavy Drinking: The Myth of Alcoholism as a Disease was published in 1988. Even as late as the mid – 1970s, sociologists were reporting that the term “alcoholic” was commonly used in the United States as synonym for “drunkard,” rather than as a designation for someone with an illness or a disorder. Apparently, in the mind of non-professionals, the contradictory notions of alcoholism as a disease and alcoholism as a moral weakness can coexist quite comfortably.

Q. The main focus of the passage is to

DIRECTIONS for the question: The five sentences (labelled 1,2,3,4, and 5) given in this question, when properly sequenced, form a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper order for the sentence and key in this sequence of five numbers as your answer.

1. This is nothing unusual.

2. It implies intense appreciation on behalf of the reader, and suggests that books in themselves are enjoyable and delicious, like warm pastries.

3. Last year, a reporter in the Guardian described how the Man Booker Prize judges spent a summer devouring novel after magnificent novel, culminating in their selection of a (baker's) dozen.

4. The language of eating is often used to describe reading habits.

5. If pressed for an explanation, one might say that to 'devour' books is to do something positive.

DIRECTIONS for the question: Identify the most appropriate summary for the paragraph.

The science of climate change does set the parameters of the problem, even though it doesn’t dictate the correct solution. It must be dealt with in the medium term, but through the structural transformation of our carbon economy rather than global austerity. That will include both developing scalable technologies for removing CO2 from the atmosphere (such as genetically modified algae and trees) and reducing the carbon intensity of our high energy life-styles (for which we already have some existing technologies, such as nuclear power). But note that such innovations require no prior global agreement to set in train, but can be developed and pioneered by a handful of big industrial economies acting on the moral concerns of their own citizens.

DIRECTIONS for the question: The five sentences (labelled 1,2,3,4 and 5) given in this question, when properly sequenced, from a coherent paragraph. Arrange them in the correct order.

1. Without the distribution and manufacturing efficiencies of the modern age, without the toll-free numbers and express delivery and bar codes and scanners and, above all, computer, the choices would not be multiplying like this.

2. Everywhere you turn, someone is offering advice on things like which of the thousands of mutual funds to buy.

3. Consumer psychologists say this sea of choices is driving us bonkers.

4. Or the right MBA program from among hundreds of business schools.

5. Superior performance in this competitive world is all about mastering business basics.

DIRECTIONS for the question: Identify the most appropriate summary for the paragraph.

Julia believed that because each person was equally valuable, she was not entitled to care more for herself than for anyone else; she believed that she was therefore obliged to spend much of her life working for the benefit of others. That was the core of it; as she grew older, she worked out the implications of this principle in greater detail. In college, she thought she might want to work in development abroad somewhere, but then she realised that probably the most useful thing she could do was not to become a white aid worker telling people in other countries what to do, but, instead, to earn a salary in the US and give it to NGOs that could use it to pay for several local workers who knew what their countries needed better than she did. She reduced her expenses to the absolute minimum so she could give away 50% of what she earned. She felt that nearly every penny she spent on herself should have gone to someone else who needed it more. She gave to whichever charity seemed to her (after researching the matter) to relieve the most suffering for the least money. All this made her worry that she might be wrong. How likely was it that everyone else was wrong and she was right? But she was also suspicious of that worry: after all, it would be quite convenient to be wrong " she would not have to give so much. Although her beliefs seemed to her not only reasonable but clearly true, and she could argue for them in a rational way, they were not entirely the result of conscious thinking: the essential impulse that gave rise to all the rest was simply a part of her. She could not help it; she had always been this way, since she was a child.

DIRECTIONS for question:

Four sentences related to a topic are given below. Three of them can be put together to form a meaningful and coherent short paragraph. Identify the odd one out. Choose its number as your answer and key it in.

1. A friend who stumbled upon my Twitter account told me that my tweets made me sound like an unrecognisable jerk. “You’re much nicer than this in real life,” she said.

2. The internet and social media change personalities of people.

3. But as face-to-face conversation becomes rarer it’s time to stop thinking that it is authentic and social media are artificial.

4. This is a common refrain about social media: that they make people behave worse than they do in “real life”.

DIRECTIONS for question:

Four sentences related to a topic are given below. Three of them can be put together to form a meaningful and coherent short paragraph. Identify the odd one out. Choose its number as your answer and key it in.

1. Some of them, former cold warriors, shared a guilty awareness of how close the planet had come to destruction as a result of accident and miscalculation.

2. In a world of failing banks and successful jihadists, nuclear weapons felt to, many like dangerous, expensive anachronisms.

3. Nuclear weapons are an effective way to make up for a lack of conventional military power—as America readily appreciated when, in the 1950s, it used the threat of retaliation with its comparatively sophisticated nuclear weapons to hold off massed Soviet tank divisions in Europe.

4. America’s superiority in conventional weapons, although not readily converted into lasting victory in real wars, was striking enough to make gradual nuclear disarmament attractive to a number of American security professionals and academics.

DIRECTIONS for the question: Identify the most appropriate summary for the paragraph.

Can I have my brain back now? I enjoyed the Olympics, and my impression is that most Britons did so too. Holidaying at home, I noticed people in pubs and shops delighting in unusual celebrities and unusual challenges, especially from the Paralympians. With Bradley Wiggins' success in the Tour de France and Andy Murray's in New York, it made for a satisfying summer of sport. Yet I saw nothing to justify the hysteria, the sobbing with joy and weeping with ecstasy, of the London media and politicians. The grasping for national pride and pseudo-psychological significance exaggerated the event and cheapened the athletes' achievement.

DIRECTIONS for question:

Four sentences related to a topic are given below. Three of them can be put together to form a meaningful and coherent short paragraph. Identify the odd one out. Choose its number as your answer and key it in.

1. For today's embattled humanities, the sciences have come to stand for the antithesis of what is now understood to constitute the content and values of a liberal education, namely: the cultivation of the intellectual and artistic traditions of diverse cultures past and present, the assertion of the generalist's prerogatives over those of the specialist, and the defense of non-utilitarian values as preparation for civic engagement in the cause of the commonweal.

2. The term "liberal education" derives from the seven medieval artesliberales(rhetoric, grammar, logic, astronomy, music, geometry and arithmetic), the knowledge necessary to a free man, by which was usually meant an adult, property-owning male who exercised the rights of citizen in the polity and pater familias in the household.

3. Some of you may be mentally re-parsing my title to something more like "Can Liberal Education Be Saved from the Sciences?"

4. In contrast, what are currently known as the STEM disciplines"science, technology, engineering and mathematics"stand for knowledge that is presumed universal and uniform, for narrow specialization and, above all, for applications that are useful and often lucrative.

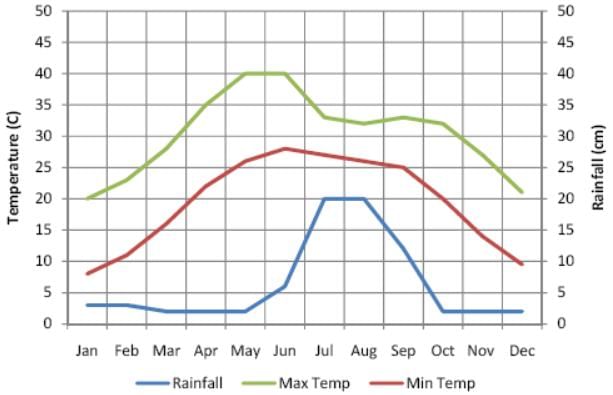

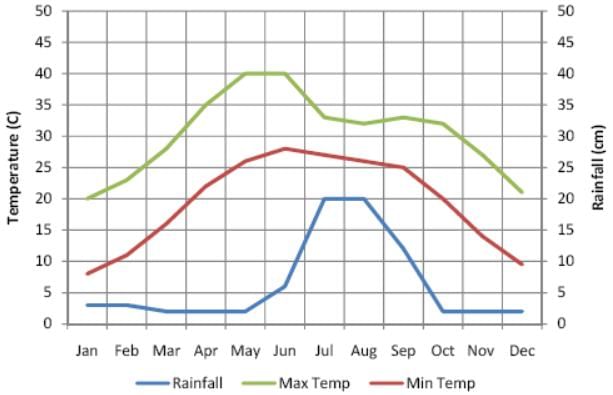

DIRECTIONS for the question: Analyse the graph/s given below and answer the question that follows.

The graph for the average temperature and rainfall seen in Delhi over the past 10 years every month referring to this graph, answer the questions below

Q. An extreme month is defined as that which has a big gap between the highest and lowest temperatures. Which is the most extreme month amongst the following?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Analyse the graph/s given below and answer the question that follows.

The graph for the average temperature and rainfall seen in Delhi over the past 10 years every month referring to this graph, answer the questions below

Q. What is the average rainfall received by Delhi every month?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Analyse the graph/s given below and answer the question that follows.

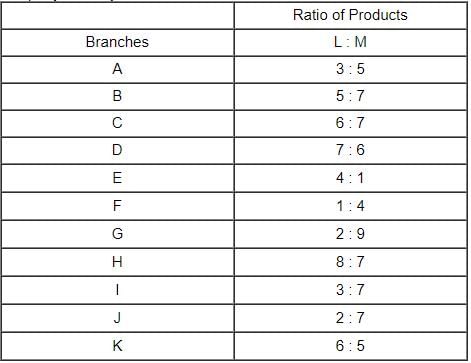

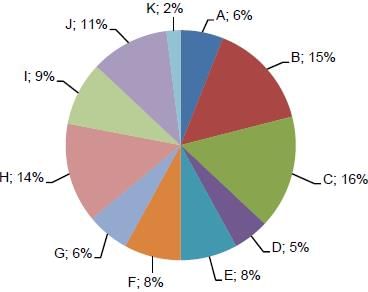

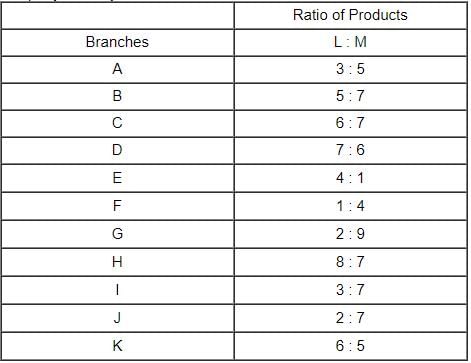

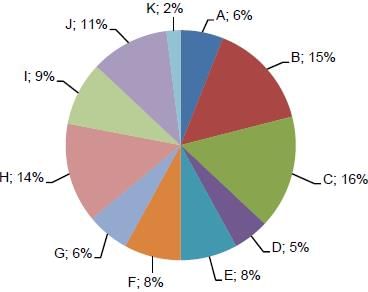

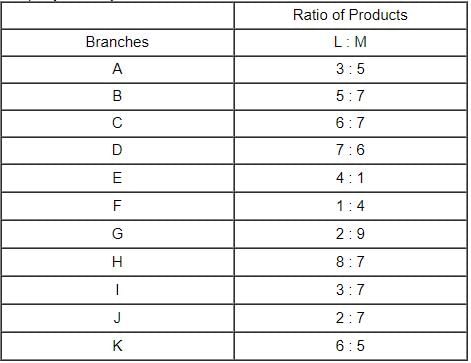

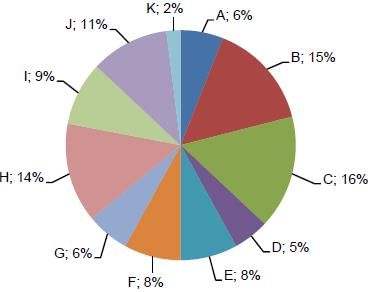

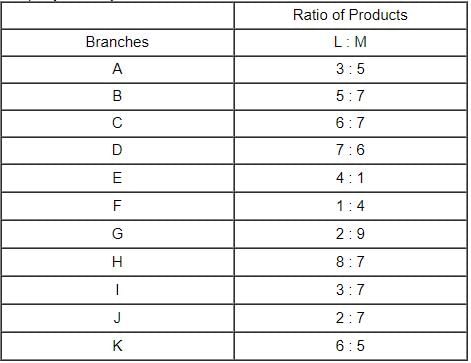

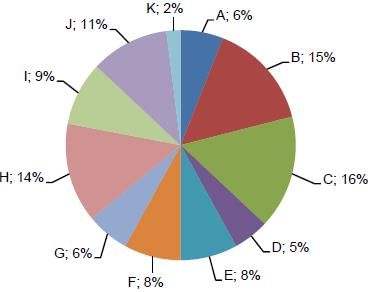

The table shows the ratio of products L and M that are produced in XYZ Company in 11 branches of that company in a day.

The diagram shows the percentage of total number of units that are produced in the different branches of XYZ Company in a day.

Q. If the total number of units of L and M is produced in branch K is 3500 then what is total number of units of M that is produced by branch I?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Analyse the graph/s given below and answer the question that follows.

The table shows the ratio of products L and M that are produced in XYZ Company in 11 branches of that company in a day.

The diagram shows the percentage of total number of units that are produced in the different branches of XYZ Company in a day.

Q. What is the ratio of the number of units of M produced by branch A to the number of units of L produced by branch B?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Analyse the graph/s given below and answer the question that follows.

The table shows the ratio of products L and M that are produced in XYZ Company in 11 branches of that company in a day.

The diagram shows the percentage of total number of units that are produced in the different branches of XYZ Company in a day.

Q. What is the ratio of the total number of units of L produced by branches E and F to the total number of units of M produced by the same branches?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Analyse the graph/s given below and answer the question that follows.

The table shows the ratio of products L and M that are produced in XYZ Company in 11 branches of that company in a day.

The diagram shows the percentage of total number of units that are produced in the different branches of XYZ Company in a day.

Q. If the total number of units of L and M produced by G is 4500, then total number of units of L that is produced by A concludes what percentage of the total number of units of M produced by E?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the information given below and answer the question that follows.

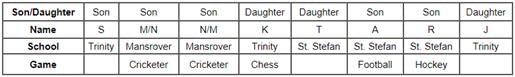

Mr. Mansingh has five sons - Arun, Mahi, Rohit, Nilesh and Sourav, and three daughters - Tamanna, Kuntala and Janaki. Three sons of Mr. Mansingh were born first followed by two daughters. Sourav is the eldest child and Janaki is the youngest. Three of the children are studying at Trinity School and three are studying at St Stefan. Tamanna and Rohit study at St Stefan school. Kuntala, the eldest daughter, plays chess. Mansorover school offers cricket only, while Trinity school offers chess. Beside, these schools offer no other games, The children who are at Mansorover school have been born in succession. Mahi and Nilesh are cricketers while Arun plays football. Rohit who was born just before Janaki, plays hockey.

Q. Arun is the ______________ child of Mr. Mansingh.