DU LLB Mock Test - 13 (New Pattern) - CLAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - DU LLB Mock Test - 13 (New Pattern)

Directions: Answer the given question based on the following passage:

History of the British parliament should not be seen as history alone, but as a historical account of certain of its leading principles and features. It is an extraordinary story. It is certainly not the tale of steady constitutional advances to which our schoolmasters have accustomed us. Looking back on the long-drawn-out processes by which each advantage was won, we cannot but be struck, not only by the intense conservatism of Englishmen in constitutional matters, but by the apparent indifference to the value of the progress already achieved. It is understandable perhaps that contemporaries should not be able to see which way the road must lead and excusable that they should tread it with hesitation. But to refuse to exploit, and to neglect and even to throw away the advantage already gained, seems to be a folly of the worst kind.

At the very moment when the Commons had secured for themselves the most fruitful of the principles of Magna Carta – the principle of consent to taxation – they minimised its power for constitutional progress by exercising it as rarely as possible. When they discovered the value of the right to petition and seemed well on the way to a monopoly of legislation, they surrendered the initiative to the Crown without a struggle. Their very privileges owed as much to the artful complaisance of a tyrant as to their own exertions.

Even the aggressive political consciousness of the seventeenth century seems almost to have been ashamed of its exuberance and shrank from using the opportunities for reform which the ascendancy of parliament conferred. Such admirable proposals for electoral reform as those of 1647 and 1653 came to nothing and the anomalies of the system continued, or rather increased, for the best part of two centuries. Cromwell's brave experiment of the 'Other House' was received without enthusiasm, and the constitution of the House of Lords still awaits reform.

Later centuries showed hardly more sense of the future. The principles of ministerial responsibility and party government, those twin pillars of the modern parliamentary system, were abhorred by most respectable statesmen of the eighteenth century. The tradition of the Speaker's neutrality, of which British parliamentarians are justly proud, is hardly a century old and owes more to the outstanding character of one or two holders of the office than to any general recognition of its necessity. It would seem indeed as if the Commons had made progress in spite of themselves.

Certainly constitutional conservatism has its compensations. As Lord Action said, 'the one thing that saved England from the fate of other countries was not her insular position, nor the independent spirit, nor the magnanimity of her people…but only the consistent, uninventive, stupid fidelity' to the political system. We have had a civil war without a prescription and a revolution without bloodshed. We have had our share of demagogues, but no one has succeeded in establishing a tyranny. For all this we may be justly thankful and take a share of the credit. Nevertheless, when we look back over the story, we cannot but recognise how much more we owe to our good fortune than to our own exertions. (History of British Parliament by Harold Laski)

Q. The author alludes to something when he says 'our schoolmasters have accustomed us'. The allusion is to

Direction: Answer the given question based on the following passage:

History of the British parliament should not be seen as history alone, but as a historical account of certain of its leading principles and features. It is an extraordinary story. It is certainly not the tale of steady constitutional advances to which our schoolmasters have accustomed us. Looking back on the long-drawn-out processes by which each advantage was won, we cannot but be struck, not only by the intense conservatism of Englishmen in constitutional matters, but by the apparent indifference to the value of the progress already achieved. It is understandable perhaps that contemporaries should not be able to see which way the road must lead and excusable that they should tread it with hesitation. But to refuse to exploit, and to neglect and even to throw away the advantage already gained, seems to be a folly of the worst kind.

At the very moment when the Commons had secured for themselves the most fruitful of the principles of Magna Carta – the principle of consent to taxation – they minimised its power for constitutional progress by exercising it as rarely as possible. When they discovered the value of the right to petition and seemed well on the way to a monopoly of legislation, they surrendered the initiative to the Crown without a struggle. Their very privileges owed as much to the artful complaisance of a tyrant as to their own exertions.

Even the aggressive political consciousness of the seventeenth century seems almost to have been ashamed of its exuberance and shrank from using the opportunities for reform which the ascendancy of parliament conferred. Such admirable proposals for electoral reform as those of 1647 and 1653 came to nothing and the anomalies of the system continued, or rather increased, for the best part of two centuries. Cromwell's brave experiment of the 'Other House' was received without enthusiasm, and the constitution of the House of Lords still awaits reform.

Later centuries showed hardly more sense of the future. The principles of ministerial responsibility and party government, those twin pillars of the modern parliamentary system, were abhorred by most respectable statesmen of the eighteenth century. The tradition of the Speaker's neutrality, of which British parliamentarians are justly proud, is hardly a century old and owes more to the outstanding character of one or two holders of the office than to any general recognition of its necessity. It would seem indeed as if the Commons had made progress in spite of themselves.

Certainly constitutional conservatism has its compensations. As Lord Action said, 'the one thing that saved England from the fate of other countries was not her insular position, nor the independent spirit, nor the magnanimity of her people…but only the consistent, uninventive, stupid fidelity' to the political system. We have had a civil war without a prescription and a revolution without bloodshed. We have had our share of demagogues, but no one has succeeded in establishing a tyranny. For all this we may be justly thankful and take a share of the credit. Nevertheless, when we look back over the story, we cannot but recognise how much more we owe to our good fortune than to our own exertions. (History of British Parliament by Harold Laski)

Q. What, according to the author, is a 'folly of the worst kind'?

Direction: Answer the given question based on the following passage:

History of the British parliament should not be seen as history alone, but as a historical account of certain of its leading principles and features. It is an extraordinary story. It is certainly not the tale of steady constitutional advances to which our schoolmasters have accustomed us. Looking back on the long-drawn-out processes by which each advantage was won, we cannot but be struck, not only by the intense conservatism of Englishmen in constitutional matters, but by the apparent indifference to the value of the progress already achieved. It is understandable perhaps that contemporaries should not be able to see which way the road must lead and excusable that they should tread it with hesitation. But to refuse to exploit, and to neglect and even to throw away the advantage already gained, seems to be a folly of the worst kind.

At the very moment when the Commons had secured for themselves the most fruitful of the principles of Magna Carta – the principle of consent to taxation – they minimised its power for constitutional progress by exercising it as rarely as possible. When they discovered the value of the right to petition and seemed well on the way to a monopoly of legislation, they surrendered the initiative to the Crown without a struggle. Their very privileges owed as much to the artful complaisance of a tyrant as to their own exertions.

Even the aggressive political consciousness of the seventeenth century seems almost to have been ashamed of its exuberance and shrank from using the opportunities for reform which the ascendancy of parliament conferred. Such admirable proposals for electoral reform as those of 1647 and 1653 came to nothing and the anomalies of the system continued, or rather increased, for the best part of two centuries. Cromwell's brave experiment of the 'Other House' was received without enthusiasm, and the constitution of the House of Lords still awaits reform.

Later centuries showed hardly more sense of the future. The principles of ministerial responsibility and party government, those twin pillars of the modern parliamentary system, were abhorred by most respectable statesmen of the eighteenth century. The tradition of the Speaker's neutrality, of which British parliamentarians are justly proud, is hardly a century old and owes more to the outstanding character of one or two holders of the office than to any general recognition of its necessity. It would seem indeed as if the Commons had made progress in spite of themselves.

Certainly constitutional conservatism has its compensations. As Lord Action said, 'the one thing that saved England from the fate of other countries was not her insular position, nor the independent spirit, nor the magnanimity of her people…but only the consistent, uninventive, stupid fidelity' to the political system. We have had a civil war without a prescription and a revolution without bloodshed. We have had our share of demagogues, but no one has succeeded in establishing a tyranny. For all this we may be justly thankful and take a share of the credit. Nevertheless, when we look back over the story, we cannot but recognise how much more we owe to our good fortune than to our own exertions. (History of British Parliament by Harold Laski)

Q. Which of the following is definitely not true in the context of the passage?

Direction: Answer the given question based on the following passage:

History of the British parliament should not be seen as history alone, but as a historical account of certain of its leading principles and features. It is an extraordinary story. It is certainly not the tale of steady constitutional advances to which our schoolmasters have accustomed us. Looking back on the long-drawn-out processes by which each advantage was won, we cannot but be struck, not only by the intense conservatism of Englishmen in constitutional matters, but by the apparent indifference to the value of the progress already achieved. It is understandable perhaps that contemporaries should not be able to see which way the road must lead and excusable that they should tread it with hesitation. But to refuse to exploit, and to neglect and even to throw away the advantage already gained, seems to be a folly of the worst kind.

At the very moment when the Commons had secured for themselves the most fruitful of the principles of Magna Carta – the principle of consent to taxation – they minimised its power for constitutional progress by exercising it as rarely as possible. When they discovered the value of the right to petition and seemed well on the way to a monopoly of legislation, they surrendered the initiative to the Crown without a struggle. Their very privileges owed as much to the artful complaisance of a tyrant as to their own exertions.

Even the aggressive political consciousness of the seventeenth century seems almost to have been ashamed of its exuberance and shrank from using the opportunities for reform which the ascendancy of parliament conferred. Such admirable proposals for electoral reform as those of 1647 and 1653 came to nothing and the anomalies of the system continued, or rather increased, for the best part of two centuries. Cromwell's brave experiment of the 'Other House' was received without enthusiasm, and the constitution of the House of Lords still awaits reform.

Later centuries showed hardly more sense of the future. The principles of ministerial responsibility and party government, those twin pillars of the modern parliamentary system, were abhorred by most respectable statesmen of the eighteenth century. The tradition of the Speaker's neutrality, of which British parliamentarians are justly proud, is hardly a century old and owes more to the outstanding character of one or two holders of the office than to any general recognition of its necessity. It would seem indeed as if the Commons had made progress in spite of themselves.

Certainly constitutional conservatism has its compensations. As Lord Action said, 'the one thing that saved England from the fate of other countries was not her insular position, nor the independent spirit, nor the magnanimity of her people…but only the consistent, uninventive, stupid fidelity' to the political system. We have had a civil war without a prescription and a revolution without bloodshed. We have had our share of demagogues, but no one has succeeded in establishing a tyranny. For all this we may be justly thankful and take a share of the credit. Nevertheless, when we look back over the story, we cannot but recognise how much more we owe to our good fortune than to our own exertions. (History of British Parliament by Harold Laski)

Q. The twin pillars of the modern parliamentary system were

Directions: The sentence given below has been divided into three parts (a), (b) and (c). One of these parts may contain an error. You have to indicate that part as your answer. If there is no error, indicate (d) as your answer.

Because he is intelligent so (a)/ I expect him (b)/ to get good marks. (c)/ No error (d)

Direction: Complete the sentence with an appropriate word from the options given:

If you ___________ respect, you get respect.

Direction: Choose a collective noun to fill in the following question.

A _______ of arrows.

Directions: Choose the synonym of the given word(s).

Convivial

Directions: Against the keyword some suggested meanings are given. Choose the word or phrase which is nearest in meaning to the keyword.

Effusion

Directions: Choose the best option to fill in the blank.

You can do your quixotic experiments with someone else; I do not wish to be your ________.

Directions: Choose the best option to fill in the blank.

The door was opened and a gust of warm air ______ at us.

Directions: Fill in the following blank.

Professional studies have become the __________ of the rich.

Directions: Fill in the following blank.

The dogs were the first to recognise the signs of the oncoming ____________.

Directions: The question given below consists of a sentence, the constituent words/phrases of which are arranged in an arbitrary way. Each separated phrase/set of words is indicated by a unique letter. Select from the alternatives provided, the option that reorganizes the phrases/set of words back into the original sentence.

(A) one important job (B) would satisfy (C) with (D) an ordinary mortal.

Directions: The question given below consists of a sentence. The constituent words/phrases are arranged in an arbitrary way. Each separated phrase/set of words is indicated by a unique letter. Select the option that reorganizes the phrases/set of words back into the original sentence.

(A) in eight weeks

(B) could

(C) houses

(D) once be built

Directions: Select the option that expresses the idea in the most clear, concise and correct manner.

Directions: Find the part of the sentence which has an error. If there is no error select (d) as your answer.

A group of (a)/ friend wants to visit (b)/ the new plant as early as possible. (c)/ No error (d)

Directions: Find the part of the sentence which has an error. If there is no error select (d) as your answer.

If I was you (a) I would not have (b) / committed this blunder. (c) / No error (d)

Directions: Find the part of the sentence which has an error. If there is no error select (d) as your answer.

Firstly, you should (a) think over the meaning of the words (b) and then use them. (c) / No error (d)

Directions: Find the part of the sentence which has an error.

The Sunrise Hotel was (a)/ fully equipped to offer (b)/ a leisure stay (c)/ to its clients. (d)

Directions: Find the part of the sentence which has an error. If there is no error select (d) as your answer.

If you lose your passport (a) in a foreign country (b) / it will affect you in a hard way. (c) / No error (d)

Directions: Select the option that expresses the central idea in the most clear, concise and correct manner.

Directions: Select the option that expresses the central idea in the most clear, concise and correct manner.

Directions: Select the option that expresses the central idea in the most clear, concise and correct manner.

Directions: Select the option that expresses the central idea in the most clear, concise and correct manner.

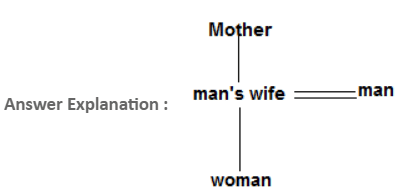

Introducing a woman, a man said, ''Her mother is the only daughter of my mother-in-law.'' How is the man related to the woman?

A tradesman marks his goods at 20% above the cost price. He allows his customers a discount of 8% on marked price. Find out his profit percent.

In a row of girls, If P is 15th from the left and Q who is 14th from the right. After interchanging their positions, P becomes 20th from the left. What is the initial position of P from right?

Directions: In the following question, there is a certain relationship between two given terms on one side of (: :) and one term is given on the other side of (: :), while another term is to be found from the given alternatives having the same relationship with this term as the terms of the given pair bear. Choose the best alternative.

Fodder : Grass : : Sentence : ?

Directions: The word pair given in the following question has a certain relationship. Select from answer choices a word pair having the same relationship.

Stretch : Shrink