CAT Mock Test - 12 - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - CAT Mock Test - 12

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

We tend to experience the olfactory realm as a shapeless suffusion, forever shifting, eluding description the way fog eludes the grasp of one's hand. Smell does not produce objects in our minds so much as auras, but these can be the most vivid of our sensory experiences. Smell is the sense most deeply entangled with memory and emotion. It functions as a kind of psychic mortar, binding together all the richness of past experience, such that a familiar scent can instantly overwhelm us with remembrance and feeling. And yet we strain to describe even the simplest odours; we retreat into simile and metaphor, or cadge the terminology of other senses, or designate smells, rather prosaically, by their source. The scent of a rose is "soft," or "rosy," or perhaps "evocative of decorous passion," but none of these descriptions would let you imagine it if you didn't know it already. Nor does smell lend itself to quantification. Sound and light fall along well-defined spectra of wavelength and frequency, but we have no such scale for odour, no metric by which to relate the aroma of cinnamon, say, to that of burnt rubber, or that of old books.

Nor can we say with certainty why anything smells the way it does. Lucretius, the Epicurean polymath, believed that odour was a function of geometry. "You cannot suppose that atoms of the same shape are entering our nostrils when stinking corpses are roasting," he wrote, "as when the stage is freshly sprinkled with saffron of Cilicia and a nearby altar exhales the perfumes of the Orient." A number of alternative theories have since been advanced. Some have imagined odours as chemical reactions between the nose and the molecules that enter it. According to "vibrational" theories, a molecule's scent depends upon its infrared or ultraviolet emissions. Shape-based theories are still the most prevalent, though, and Lucretius is thought to have been basically right, apart from the correlation he imagined between harmoniousness of form and loveliness of smell. The scent of a rose is the combined effect of about 260 volatile compounds, some as jagged as the flower's thorns.

If shape does indeed account for smell, however, we are far from knowing exactly how. Molecules of widely divergent structure can smell nearly identical. Muscone and Helvetolide, for instance, both smell of musk, but one is shaped like a ring, the other a kinked chain. Conversely, molecules of nearly identical structure produce odours that are completely distinct. The compound L-carvone smells of spearmint, while its mirror image, D-carvone, smells of caraway seed. Certain substances have unrelated smells at different concentrations. Gamma-undecalactone generally smells fatty and aversive. Heavily diluted, it smells of ripened peach.

We speak of scent as if it were a property intrinsic to a given substance, but odour is not simply "out there." It is a co-creation of the nose. At the very top of the nasal cavity, up between the eyes, sits mucosal tissue known as the olfactory epithelium. It is dense with neurons, and embedded in these neurons are proteins known as odourant receptors. Odourant receptors bind the volatile compounds we inhale, converting them into electric signals that will, eventually, register in our consciousness as smell. The nature of these receptors—how many kinds there are, which molecules they respond to—is central to our experience of scent. It is also, for the most part, a mystery.

Q. In the phrase 'Lucretius is thought to have been basically right ... and loveliness of smell', which of the following statements is the author trying to imply?

Nor can we say with certainty why anything smells the way it does. Lucretius, the Epicurean polymath, believed that odour was a function of geometry. "You cannot suppose that atoms of the same shape are entering our nostrils when stinking corpses are roasting," he wrote, "as when the stage is freshly sprinkled with saffron of Cilicia and a nearby altar exhales the perfumes of the Orient." A number of alternative theories have since been advanced. Some have imagined odours as chemical reactions between the nose and the molecules that enter it. According to "vibrational" theories, a molecule's scent depends upon its infrared or ultraviolet emissions. Shape-based theories are still the most prevalent, though, and Lucretius is thought to have been basically right, apart from the correlation he imagined between harmoniousness of form and loveliness of smell. The scent of a rose is the combined effect of about 260 volatile compounds, some as jagged as the flower's thorns.

If shape does indeed account for smell, however, we are far from knowing exactly how. Molecules of widely divergent structure can smell nearly identical. Muscone and Helvetolide, for instance, both smell of musk, but one is shaped like a ring, the other a kinked chain. Conversely, molecules of nearly identical structure produce odours that are completely distinct. The compound L-carvone smells of spearmint, while its mirror image, D-carvone, smells of caraway seed. Certain substances have unrelated smells at different concentrations. Gamma-undecalactone generally smells fatty and aversive. Heavily diluted, it smells of ripened peach.

We speak of scent as if it were a property intrinsic to a given substance, but odour is not simply "out there." It is a co-creation of the nose. At the very top of the nasal cavity, up between the eyes, sits mucosal tissue known as the olfactory epithelium. It is dense with neurons, and embedded in these neurons are proteins known as odourant receptors. Odourant receptors bind the volatile compounds we inhale, converting them into electric signals that will, eventually, register in our consciousness as smell. The nature of these receptors—how many kinds there are, which molecules they respond to—is central to our experience of scent. It is also, for the most part, a mystery.

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

We tend to experience the olfactory realm as a shapeless suffusion, forever shifting, eluding description the way fog eludes the grasp of one's hand. Smell does not produce objects in our minds so much as auras, but these can be the most vivid of our sensory experiences. Smell is the sense most deeply entangled with memory and emotion. It functions as a kind of psychic mortar, binding together all the richness of past experience, such that a familiar scent can instantly overwhelm us with remembrance and feeling. And yet we strain to describe even the simplest odours; we retreat into simile and metaphor, or cadge the terminology of other senses, or designate smells, rather prosaically, by their source. The scent of a rose is "soft," or "rosy," or perhaps "evocative of decorous passion," but none of these descriptions would let you imagine it if you didn't know it already. Nor does smell lend itself to quantification. Sound and light fall along well-defined spectra of wavelength and frequency, but we have no such scale for odour, no metric by which to relate the aroma of cinnamon, say, to that of burnt rubber, or that of old books.

Nor can we say with certainty why anything smells the way it does. Lucretius, the Epicurean polymath, believed that odour was a function of geometry. "You cannot suppose that atoms of the same shape are entering our nostrils when stinking corpses are roasting," he wrote, "as when the stage is freshly sprinkled with saffron of Cilicia and a nearby altar exhales the perfumes of the Orient." A number of alternative theories have since been advanced. Some have imagined odours as chemical reactions between the nose and the molecules that enter it. According to "vibrational" theories, a molecule's scent depends upon its infrared or ultraviolet emissions. Shape-based theories are still the most prevalent, though, and Lucretius is thought to have been basically right, apart from the correlation he imagined between harmoniousness of form and loveliness of smell. The scent of a rose is the combined effect of about 260 volatile compounds, some as jagged as the flower's thorns.

If shape does indeed account for smell, however, we are far from knowing exactly how. Molecules of widely divergent structure can smell nearly identical. Muscone and Helvetolide, for instance, both smell of musk, but one is shaped like a ring, the other a kinked chain. Conversely, molecules of nearly identical structure produce odours that are completely distinct. The compound L-carvone smells of spearmint, while its mirror image, D-carvone, smells of caraway seed. Certain substances have unrelated smells at different concentrations. Gamma-undecalactone generally smells fatty and aversive. Heavily diluted, it smells of ripened peach.

We speak of scent as if it were a property intrinsic to a given substance, but odour is not simply "out there." It is a co-creation of the nose. At the very top of the nasal cavity, up between the eyes, sits mucosal tissue known as the olfactory epithelium. It is dense with neurons, and embedded in these neurons are proteins known as odourant receptors. Odourant receptors bind the volatile compounds we inhale, converting them into electric signals that will, eventually, register in our consciousness as smell. The nature of these receptors—how many kinds there are, which molecules they respond to—is central to our experience of scent. It is also, for the most part, a mystery.

Q. Which of the following, according to the author, can be inferred as a flaw in the present approaches to understand the concept of smell and scent?

Nor can we say with certainty why anything smells the way it does. Lucretius, the Epicurean polymath, believed that odour was a function of geometry. "You cannot suppose that atoms of the same shape are entering our nostrils when stinking corpses are roasting," he wrote, "as when the stage is freshly sprinkled with saffron of Cilicia and a nearby altar exhales the perfumes of the Orient." A number of alternative theories have since been advanced. Some have imagined odours as chemical reactions between the nose and the molecules that enter it. According to "vibrational" theories, a molecule's scent depends upon its infrared or ultraviolet emissions. Shape-based theories are still the most prevalent, though, and Lucretius is thought to have been basically right, apart from the correlation he imagined between harmoniousness of form and loveliness of smell. The scent of a rose is the combined effect of about 260 volatile compounds, some as jagged as the flower's thorns.

If shape does indeed account for smell, however, we are far from knowing exactly how. Molecules of widely divergent structure can smell nearly identical. Muscone and Helvetolide, for instance, both smell of musk, but one is shaped like a ring, the other a kinked chain. Conversely, molecules of nearly identical structure produce odours that are completely distinct. The compound L-carvone smells of spearmint, while its mirror image, D-carvone, smells of caraway seed. Certain substances have unrelated smells at different concentrations. Gamma-undecalactone generally smells fatty and aversive. Heavily diluted, it smells of ripened peach.

We speak of scent as if it were a property intrinsic to a given substance, but odour is not simply "out there." It is a co-creation of the nose. At the very top of the nasal cavity, up between the eyes, sits mucosal tissue known as the olfactory epithelium. It is dense with neurons, and embedded in these neurons are proteins known as odourant receptors. Odourant receptors bind the volatile compounds we inhale, converting them into electric signals that will, eventually, register in our consciousness as smell. The nature of these receptors—how many kinds there are, which molecules they respond to—is central to our experience of scent. It is also, for the most part, a mystery.

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

We tend to experience the olfactory realm as a shapeless suffusion, forever shifting, eluding description the way fog eludes the grasp of one's hand. Smell does not produce objects in our minds so much as auras, but these can be the most vivid of our sensory experiences. Smell is the sense most deeply entangled with memory and emotion. It functions as a kind of psychic mortar, binding together all the richness of past experience, such that a familiar scent can instantly overwhelm us with remembrance and feeling. And yet we strain to describe even the simplest odours; we retreat into simile and metaphor, or cadge the terminology of other senses, or designate smells, rather prosaically, by their source. The scent of a rose is "soft," or "rosy," or perhaps "evocative of decorous passion," but none of these descriptions would let you imagine it if you didn't know it already. Nor does smell lend itself to quantification. Sound and light fall along well-defined spectra of wavelength and frequency, but we have no such scale for odour, no metric by which to relate the aroma of cinnamon, say, to that of burnt rubber, or that of old books.

Nor can we say with certainty why anything smells the way it does. Lucretius, the Epicurean polymath, believed that odour was a function of geometry. "You cannot suppose that atoms of the same shape are entering our nostrils when stinking corpses are roasting," he wrote, "as when the stage is freshly sprinkled with saffron of Cilicia and a nearby altar exhales the perfumes of the Orient." A number of alternative theories have since been advanced. Some have imagined odours as chemical reactions between the nose and the molecules that enter it. According to "vibrational" theories, a molecule's scent depends upon its infrared or ultraviolet emissions. Shape-based theories are still the most prevalent, though, and Lucretius is thought to have been basically right, apart from the correlation he imagined between harmoniousness of form and loveliness of smell. The scent of a rose is the combined effect of about 260 volatile compounds, some as jagged as the flower's thorns.

If shape does indeed account for smell, however, we are far from knowing exactly how. Molecules of widely divergent structure can smell nearly identical. Muscone and Helvetolide, for instance, both smell of musk, but one is shaped like a ring, the other a kinked chain. Conversely, molecules of nearly identical structure produce odours that are completely distinct. The compound L-carvone smells of spearmint, while its mirror image, D-carvone, smells of caraway seed. Certain substances have unrelated smells at different concentrations. Gamma-undecalactone generally smells fatty and aversive. Heavily diluted, it smells of ripened peach.

We speak of scent as if it were a property intrinsic to a given substance, but odour is not simply "out there." It is a co-creation of the nose. At the very top of the nasal cavity, up between the eyes, sits mucosal tissue known as the olfactory epithelium. It is dense with neurons, and embedded in these neurons are proteins known as odourant receptors. Odourant receptors bind the volatile compounds we inhale, converting them into electric signals that will, eventually, register in our consciousness as smell. The nature of these receptors—how many kinds there are, which molecules they respond to—is central to our experience of scent. It is also, for the most part, a mystery.

Q. The author of the passage is most likely to agree with which of the following statements?

Nor can we say with certainty why anything smells the way it does. Lucretius, the Epicurean polymath, believed that odour was a function of geometry. "You cannot suppose that atoms of the same shape are entering our nostrils when stinking corpses are roasting," he wrote, "as when the stage is freshly sprinkled with saffron of Cilicia and a nearby altar exhales the perfumes of the Orient." A number of alternative theories have since been advanced. Some have imagined odours as chemical reactions between the nose and the molecules that enter it. According to "vibrational" theories, a molecule's scent depends upon its infrared or ultraviolet emissions. Shape-based theories are still the most prevalent, though, and Lucretius is thought to have been basically right, apart from the correlation he imagined between harmoniousness of form and loveliness of smell. The scent of a rose is the combined effect of about 260 volatile compounds, some as jagged as the flower's thorns.

If shape does indeed account for smell, however, we are far from knowing exactly how. Molecules of widely divergent structure can smell nearly identical. Muscone and Helvetolide, for instance, both smell of musk, but one is shaped like a ring, the other a kinked chain. Conversely, molecules of nearly identical structure produce odours that are completely distinct. The compound L-carvone smells of spearmint, while its mirror image, D-carvone, smells of caraway seed. Certain substances have unrelated smells at different concentrations. Gamma-undecalactone generally smells fatty and aversive. Heavily diluted, it smells of ripened peach.

We speak of scent as if it were a property intrinsic to a given substance, but odour is not simply "out there." It is a co-creation of the nose. At the very top of the nasal cavity, up between the eyes, sits mucosal tissue known as the olfactory epithelium. It is dense with neurons, and embedded in these neurons are proteins known as odourant receptors. Odourant receptors bind the volatile compounds we inhale, converting them into electric signals that will, eventually, register in our consciousness as smell. The nature of these receptors—how many kinds there are, which molecules they respond to—is central to our experience of scent. It is also, for the most part, a mystery.

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

We tend to experience the olfactory realm as a shapeless suffusion, forever shifting, eluding description the way fog eludes the grasp of one's hand. Smell does not produce objects in our minds so much as auras, but these can be the most vivid of our sensory experiences. Smell is the sense most deeply entangled with memory and emotion. It functions as a kind of psychic mortar, binding together all the richness of past experience, such that a familiar scent can instantly overwhelm us with remembrance and feeling. And yet we strain to describe even the simplest odours; we retreat into simile and metaphor, or cadge the terminology of other senses, or designate smells, rather prosaically, by their source. The scent of a rose is "soft," or "rosy," or perhaps "evocative of decorous passion," but none of these descriptions would let you imagine it if you didn't know it already. Nor does smell lend itself to quantification. Sound and light fall along well-defined spectra of wavelength and frequency, but we have no such scale for odour, no metric by which to relate the aroma of cinnamon, say, to that of burnt rubber, or that of old books.

Nor can we say with certainty why anything smells the way it does. Lucretius, the Epicurean polymath, believed that odour was a function of geometry. "You cannot suppose that atoms of the same shape are entering our nostrils when stinking corpses are roasting," he wrote, "as when the stage is freshly sprinkled with saffron of Cilicia and a nearby altar exhales the perfumes of the Orient." A number of alternative theories have since been advanced. Some have imagined odours as chemical reactions between the nose and the molecules that enter it. According to "vibrational" theories, a molecule's scent depends upon its infrared or ultraviolet emissions. Shape-based theories are still the most prevalent, though, and Lucretius is thought to have been basically right, apart from the correlation he imagined between harmoniousness of form and loveliness of smell. The scent of a rose is the combined effect of about 260 volatile compounds, some as jagged as the flower's thorns.

If shape does indeed account for smell, however, we are far from knowing exactly how. Molecules of widely divergent structure can smell nearly identical. Muscone and Helvetolide, for instance, both smell of musk, but one is shaped like a ring, the other a kinked chain. Conversely, molecules of nearly identical structure produce odours that are completely distinct. The compound L-carvone smells of spearmint, while its mirror image, D-carvone, smells of caraway seed. Certain substances have unrelated smells at different concentrations. Gamma-undecalactone generally smells fatty and aversive. Heavily diluted, it smells of ripened peach.

We speak of scent as if it were a property intrinsic to a given substance, but odour is not simply "out there." It is a co-creation of the nose. At the very top of the nasal cavity, up between the eyes, sits mucosal tissue known as the olfactory epithelium. It is dense with neurons, and embedded in these neurons are proteins known as odourant receptors. Odourant receptors bind the volatile compounds we inhale, converting them into electric signals that will, eventually, register in our consciousness as smell. The nature of these receptors—how many kinds there are, which molecules they respond to—is central to our experience of scent. It is also, for the most part, a mystery.

Q. '...odour is not simply out there. It is a co-creation of the nose'. It can be inferred from this that the author is trying to imply which of the following?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the given question.

Claude Lorrain and Carle Vernet are considered by the Impressionists as precursors from the point of view of decorative landscape arrangement, and particularly of the predominance of light in which all objects are bathed. Ruysdael and Poussin are, in their eyes, for the same reasons precursors who observed so frankly the blue colouring of the horizon and the influence of blue upon the landscape. It is known that Turner worshipped Claude for the very same reasons. The Impressionists in their turn consider Turner as one of their mighty geniuses, a visionary. Notably in the famous Entry of the Crusaders into Constantinople, the fair woman kneeling in the foreground is painted in accordance with the principles of the division of tones: the nude back is furrowed with blue, green and yellow touches, the juxtaposition of which produces, at a certain distance, an admirable flesh-tone.

And now I must speak at some length of a painter who, together with the luminous and sparkling landscapist Félix Ziem, was the most direct initiator of Impressionist technique. Monticelli is one of those singular men of genius who are not connected with any school, and whose work is an inexhaustible source of applications. He lived at Marseilles, where he was born, made a short appearance at the Salons, and then returned to his native town, where he died poor, ignored, paralysed and mad.

In order to live he sold his small pictures at the cafés, where they fetched ten or twenty francs at the most. Today they sell for considerable prices. The mysterious power of these paintings secures him a fame which is, alas! posthumous. Many Monticellis have been sold by dealers as Diaz's; now they are more eagerly looked for than Diaz, and collectors have made fortunes with these small canvases bought formerly, to use a colloquial expression which is here only too literally true, ''for a piece of bread.''

Monticelli painted landscapes, romantic scenes, and still-life pictures: one could not imagine a more inspired sense of colour than shown by these works which seem to be painted with crushed jewels, with powerful harmony, and beyond all with an unheard-of delicacy in the perception of fine shades. There are tones which nobody had ever invented yet, a richness, a profusion, a subtlety which almost vie with the resources of music. The fairyland atmosphere of these works surrounds a very firm design of charming style, but, to use the words of the artist himself, ''in these canvases the objects are the decoration, the touches are the scales, and the light is the tenor.'' Monticelli has created for himself an entirely personal technique which can only be compared with that of Turner; he painted with a brush so full, fat and rich, that some of the details are often truly modelled in relief, in a substance as precious as enamels, jewels, ceramics - a substance which is a delight in itself. Every picture by Monticelli provokes astonishment; constructed upon one colour as upon a musical theme, it rises to intensities which one would have thought impossible. His pictures are magnificent bouquets, bursts of joy and colour, where nothing is ever crude, and where everything is ruled by a supreme sense of harmony.

Q. According to the passage, in which of the following ways was the work of early Impressionist masters significantly different in style?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the given question.

Claude Lorrain and Carle Vernet are considered by the Impressionists as precursors from the point of view of decorative landscape arrangement, and particularly of the predominance of light in which all objects are bathed. Ruysdael and Poussin are, in their eyes, for the same reasons precursors who observed so frankly the blue colouring of the horizon and the influence of blue upon the landscape. It is known that Turner worshipped Claude for the very same reasons. The Impressionists in their turn consider Turner as one of their mighty geniuses, a visionary. Notably in the famous Entry of the Crusaders into Constantinople, the fair woman kneeling in the foreground is painted in accordance with the principles of the division of tones: the nude back is furrowed with blue, green and yellow touches, the juxtaposition of which produces, at a certain distance, an admirable flesh-tone.

And now I must speak at some length of a painter who, together with the luminous and sparkling landscapist Félix Ziem, was the most direct initiator of Impressionist technique. Monticelli is one of those singular men of genius who are not connected with any school, and whose work is an inexhaustible source of applications. He lived at Marseilles, where he was born, made a short appearance at the Salons, and then returned to his native town, where he died poor, ignored, paralysed and mad.

In order to live he sold his small pictures at the cafés, where they fetched ten or twenty francs at the most. Today they sell for considerable prices. The mysterious power of these paintings secures him a fame which is, alas! posthumous. Many Monticellis have been sold by dealers as Diaz's; now they are more eagerly looked for than Diaz, and collectors have made fortunes with these small canvases bought formerly, to use a colloquial expression which is here only too literally true, ''for a piece of bread.''

Monticelli painted landscapes, romantic scenes, and still-life pictures: one could not imagine a more inspired sense of colour than shown by these works which seem to be painted with crushed jewels, with powerful harmony, and beyond all with an unheard-of delicacy in the perception of fine shades. There are tones which nobody had ever invented yet, a richness, a profusion, a subtlety which almost vie with the resources of music. The fairyland atmosphere of these works surrounds a very firm design of charming style, but, to use the words of the artist himself, ''in these canvases the objects are the decoration, the touches are the scales, and the light is the tenor.'' Monticelli has created for himself an entirely personal technique which can only be compared with that of Turner; he painted with a brush so full, fat and rich, that some of the details are often truly modelled in relief, in a substance as precious as enamels, jewels, ceramics - a substance which is a delight in itself. Every picture by Monticelli provokes astonishment; constructed upon one colour as upon a musical theme, it rises to intensities which one would have thought impossible. His pictures are magnificent bouquets, bursts of joy and colour, where nothing is ever crude, and where everything is ruled by a supreme sense of harmony.

Q. From the passage, it can be inferred that the painting 'Entry of the Crusaders into Constantinople' is truly symbolic of Impressionist art due to:

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the given question.

Claude Lorrain and Carle Vernet are considered by the Impressionists as precursors from the point of view of decorative landscape arrangement, and particularly of the predominance of light in which all objects are bathed. Ruysdael and Poussin are, in their eyes, for the same reasons precursors who observed so frankly the blue colouring of the horizon and the influence of blue upon the landscape. It is known that Turner worshipped Claude for the very same reasons. The Impressionists in their turn consider Turner as one of their mighty geniuses, a visionary. Notably in the famous Entry of the Crusaders into Constantinople, the fair woman kneeling in the foreground is painted in accordance with the principles of the division of tones: the nude back is furrowed with blue, green and yellow touches, the juxtaposition of which produces, at a certain distance, an admirable flesh-tone.

And now I must speak at some length of a painter who, together with the luminous and sparkling landscapist Félix Ziem, was the most direct initiator of Impressionist technique. Monticelli is one of those singular men of genius who are not connected with any school, and whose work is an inexhaustible source of applications. He lived at Marseilles, where he was born, made a short appearance at the Salons, and then returned to his native town, where he died poor, ignored, paralysed and mad.

In order to live he sold his small pictures at the cafés, where they fetched ten or twenty francs at the most. Today they sell for considerable prices. The mysterious power of these paintings secures him a fame which is, alas! posthumous. Many Monticellis have been sold by dealers as Diaz's; now they are more eagerly looked for than Diaz, and collectors have made fortunes with these small canvases bought formerly, to use a colloquial expression which is here only too literally true, ''for a piece of bread.''

Monticelli painted landscapes, romantic scenes, and still-life pictures: one could not imagine a more inspired sense of colour than shown by these works which seem to be painted with crushed jewels, with powerful harmony, and beyond all with an unheard-of delicacy in the perception of fine shades. There are tones which nobody had ever invented yet, a richness, a profusion, a subtlety which almost vie with the resources of music. The fairyland atmosphere of these works surrounds a very firm design of charming style, but, to use the words of the artist himself, ''in these canvases the objects are the decoration, the touches are the scales, and the light is the tenor.'' Monticelli has created for himself an entirely personal technique which can only be compared with that of Turner; he painted with a brush so full, fat and rich, that some of the details are often truly modelled in relief, in a substance as precious as enamels, jewels, ceramics - a substance which is a delight in itself. Every picture by Monticelli provokes astonishment; constructed upon one colour as upon a musical theme, it rises to intensities which one would have thought impossible. His pictures are magnificent bouquets, bursts of joy and colour, where nothing is ever crude, and where everything is ruled by a supreme sense of harmony.

Q. Which of the following is stated by the author as Monticelli's contribution to the world of art?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the given question.

Claude Lorrain and Carle Vernet are considered by the Impressionists as precursors from the point of view of decorative landscape arrangement, and particularly of the predominance of light in which all objects are bathed. Ruysdael and Poussin are, in their eyes, for the same reasons precursors who observed so frankly the blue colouring of the horizon and the influence of blue upon the landscape. It is known that Turner worshipped Claude for the very same reasons. The Impressionists in their turn consider Turner as one of their mighty geniuses, a visionary. Notably in the famous Entry of the Crusaders into Constantinople, the fair woman kneeling in the foreground is painted in accordance with the principles of the division of tones: the nude back is furrowed with blue, green and yellow touches, the juxtaposition of which produces, at a certain distance, an admirable flesh-tone.

And now I must speak at some length of a painter who, together with the luminous and sparkling landscapist Félix Ziem, was the most direct initiator of Impressionist technique. Monticelli is one of those singular men of genius who are not connected with any school, and whose work is an inexhaustible source of applications. He lived at Marseilles, where he was born, made a short appearance at the Salons, and then returned to his native town, where he died poor, ignored, paralysed and mad.

In order to live he sold his small pictures at the cafés, where they fetched ten or twenty francs at the most. Today they sell for considerable prices. The mysterious power of these paintings secures him a fame which is, alas! posthumous. Many Monticellis have been sold by dealers as Diaz's; now they are more eagerly looked for than Diaz, and collectors have made fortunes with these small canvases bought formerly, to use a colloquial expression which is here only too literally true, ''for a piece of bread.''

Monticelli painted landscapes, romantic scenes, and still-life pictures: one could not imagine a more inspired sense of colour than shown by these works which seem to be painted with crushed jewels, with powerful harmony, and beyond all with an unheard-of delicacy in the perception of fine shades. There are tones which nobody had ever invented yet, a richness, a profusion, a subtlety which almost vie with the resources of music. The fairyland atmosphere of these works surrounds a very firm design of charming style, but, to use the words of the artist himself, ''in these canvases the objects are the decoration, the touches are the scales, and the light is the tenor.'' Monticelli has created for himself an entirely personal technique which can only be compared with that of Turner; he painted with a brush so full, fat and rich, that some of the details are often truly modelled in relief, in a substance as precious as enamels, jewels, ceramics - a substance which is a delight in itself. Every picture by Monticelli provokes astonishment; constructed upon one colour as upon a musical theme, it rises to intensities which one would have thought impossible. His pictures are magnificent bouquets, bursts of joy and colour, where nothing is ever crude, and where everything is ruled by a supreme sense of harmony.

Q. It can be inferred from the passage that apart from being a great artist, Monticelli led a life that exemplified

Directions: The passage below is followed by a question based on its content. Answer the question on the basis of what is stated or implied in the passage.

The incisive observations entrenched in Parmenides' Eleatic as we know it may actually have originated in Parmenides' lecture notes, or even those of one of his students. Regardless of the origin, Kepler refers to Eleatic, written prior to 323 B.C., as "one of the most enlightening and dominant books ever produced by the human intellect".

Even though it cannot be disputed that translations of Parmenides' work were available at other places also, no proof exists demonstrating that European scholars had access to it between the fifth and ninth centuries. Parmenides was known in Turkey, and a Nestorian monk of the ninth century translated the Eleatic into Turkish from a complete Greek manuscript that is now lost. The work was translated from the Turkish in Arabic in the year 935; from this translation Altamsh of Kardaba, an Islamic philosopher, fashioned a condensed translation in the 12th century projected to "determine how much of Parmenides' book on poetry is concerned with universal rules common to all nations or to most; for most of what is found in this book consists either of rules proper to their poetry and their usage, or they are found in Arabian poetry, or they are found in other languages." Altamsh replaced Arabic examples for the Greek, possessed no notion of literature being a simulation of life, and failed to realise much of the sense of the treatise. It was, however, Altamsh's translation, translated into Latin by Herart Eledir in the thirteenth century, published in Venice in 1481 and reprinted in 1515, that was the first medium enabling Renaissance scholars to judge the content of Eleatic. This version of Eleatic circulated freely, leaving no signs that it influenced critical literature. The practice of translations into Latin (1498), into Greek by Erasmus in 1532, and into Italian by Guini in 1594 has been documented.

When the Italian Renaissance scholars were able to consider the work of Parmenides, the result was twisted not only by the number of quality of translation, but also by the nature of the Italian Renaissance itself, questions of the wished-for meaning of main words and phrases, and the enveloping influence of Horace and the ancient.

The Italians' particular ardour for form established the groundwork for the propagation of Parmenidian "rules," which evolved from faultily construed principles of the Eleatic and incorporated the add-ons of unity of place, elucidation of "nobility" to denote noticeable nobility, the Quintian five acts, and a subjective segregation of a fourth person in dialogue. In Gihhin Jinthos's work, Parmenides's prerequisite that the poet, in contrast to the historian, relate what could happen is interpreted as a requirement that the poetry represents things as they should occur. Other scholars freely amplified Parmenides' work, completing his statements by adding much of the collection of medieval guidelines and a heavy amount of Christian contemplation.

Parmenides is generally understood to have wanted that the tragic hero be "noble." Italian scholars interpreted that the tragic hero be highly famed and affluent, and the status of the actors became such a significant deliberation in the Renaissance that it was sensed to be the distinctive factor between comedy and tragedy. Other facets of drama – scheme, vista, number of players, and poetry – were caste by this construal.

Q. Which of the following statements best summarises the central idea of the passage?

Directions: The passage below is followed by a question based on its content. Answer the question on the basis of what is stated or implied in the passage.

The incisive observations entrenched in Parmenides' Eleatic as we know it may actually have originated in Parmenides' lecture notes, or even those of one of his students. Regardless of the origin, Kepler refers to Eleatic, written prior to 323 B.C., as "one of the most enlightening and dominant books ever produced by the human intellect".

Even though it cannot be disputed that translations of Parmenides' work were available at other places also, no proof exists demonstrating that European scholars had access to it between the fifth and ninth centuries. Parmenides was known in Turkey, and a Nestorian monk of the ninth century translated the Eleatic into Turkish from a complete Greek manuscript that is now lost. The work was translated from the Turkish in Arabic in the year 935; from this translation Altamsh of Kardaba, an Islamic philosopher, fashioned a condensed translation in the 12th century projected to "determine how much of Parmenides' book on poetry is concerned with universal rules common to all nations or to most; for most of what is found in this book consists either of rules proper to their poetry and their usage, or they are found in Arabian poetry, or they are found in other languages." Altamsh replaced Arabic examples for the Greek, possessed no notion of literature being a simulation of life, and failed to realise much of the sense of the treatise. It was, however, Altamsh's translation, translated into Latin by Herart Eledir in the thirteenth century, published in Venice in 1481 and reprinted in 1515, that was the first medium enabling Renaissance scholars to judge the content of Eleatic. This version of Eleatic circulated freely, leaving no signs that it influenced critical literature. The practice of translations into Latin (1498), into Greek by Erasmus in 1532, and into Italian by Guini in 1594 has been documented.

When the Italian Renaissance scholars were able to consider the work of Parmenides, the result was twisted not only by the number of quality of translation, but also by the nature of the Italian Renaissance itself, questions of the wished-for meaning of main words and phrases, and the enveloping influence of Horace and the ancient.

The Italians' particular ardour for form established the groundwork for the propagation of Parmenidian "rules," which evolved from faultily construed principles of the Eleatic and incorporated the add-ons of unity of place, elucidation of "nobility" to denote noticeable nobility, the Quintian five acts, and a subjective segregation of a fourth person in dialogue. In Gihhin Jinthos's work, Parmenides's prerequisite that the poet, in contrast to the historian, relate what could happen is interpreted as a requirement that the poetry represents things as they should occur. Other scholars freely amplified Parmenides' work, completing his statements by adding much of the collection of medieval guidelines and a heavy amount of Christian contemplation.

Parmenides is generally understood to have wanted that the tragic hero be "noble." Italian scholars interpreted that the tragic hero be highly famed and affluent, and the status of the actors became such a significant deliberation in the Renaissance that it was sensed to be the distinctive factor between comedy and tragedy. Other facets of drama – scheme, vista, number of players, and poetry – were caste by this construal.

Q. Which of the following options best states the function of the third paragraph in the overall context of the passage?

Directions: The passage below is followed by a question based on its content. Answer the question on the basis of what is stated or implied in the passage.

The incisive observations entrenched in Parmenides' Eleatic as we know it may actually have originated in Parmenides' lecture notes, or even those of one of his students. Regardless of the origin, Kepler refers to Eleatic, written prior to 323 B.C., as "one of the most enlightening and dominant books ever produced by the human intellect".

Even though it cannot be disputed that translations of Parmenides' work were available at other places also, no proof exists demonstrating that European scholars had access to it between the fifth and ninth centuries. Parmenides was known in Turkey, and a Nestorian monk of the ninth century translated the Eleatic into Turkish from a complete Greek manuscript that is now lost. The work was translated from the Turkish in Arabic in the year 935; from this translation Altamsh of Kardaba, an Islamic philosopher, fashioned a condensed translation in the 12th century projected to "determine how much of Parmenides' book on poetry is concerned with universal rules common to all nations or to most; for most of what is found in this book consists either of rules proper to their poetry and their usage, or they are found in Arabian poetry, or they are found in other languages." Altamsh replaced Arabic examples for the Greek, possessed no notion of literature being a simulation of life, and failed to realise much of the sense of the treatise. It was, however, Altamsh's translation, translated into Latin by Herart Eledir in the thirteenth century, published in Venice in 1481 and reprinted in 1515, that was the first medium enabling Renaissance scholars to judge the content of Eleatic. This version of Eleatic circulated freely, leaving no signs that it influenced critical literature. The practice of translations into Latin (1498), into Greek by Erasmus in 1532, and into Italian by Guini in 1594 has been documented.

When the Italian Renaissance scholars were able to consider the work of Parmenides, the result was twisted not only by the number of quality of translation, but also by the nature of the Italian Renaissance itself, questions of the wished-for meaning of main words and phrases, and the enveloping influence of Horace and the ancient.

The Italians' particular ardour for form established the groundwork for the propagation of Parmenidian "rules," which evolved from faultily construed principles of the Eleatic and incorporated the add-ons of unity of place, elucidation of "nobility" to denote noticeable nobility, the Quintian five acts, and a subjective segregation of a fourth person in dialogue. In Gihhin Jinthos's work, Parmenides's prerequisite that the poet, in contrast to the historian, relate what could happen is interpreted as a requirement that the poetry represents things as they should occur. Other scholars freely amplified Parmenides' work, completing his statements by adding much of the collection of medieval guidelines and a heavy amount of Christian contemplation.

Parmenides is generally understood to have wanted that the tragic hero be "noble." Italian scholars interpreted that the tragic hero be highly famed and affluent, and the status of the actors became such a significant deliberation in the Renaissance that it was sensed to be the distinctive factor between comedy and tragedy. Other facets of drama – scheme, vista, number of players, and poetry – were caste by this construal.

Q. Which of the following had the LEAST influence upon Renaissance's interpretation of Parmenides?

Directions: The passage below is followed by a question based on its content. Answer the question on the basis of what is stated or implied in the passage.

The incisive observations entrenched in Parmenides' Eleatic as we know it may actually have originated in Parmenides' lecture notes, or even those of one of his students. Regardless of the origin, Kepler refers to Eleatic, written prior to 323 B.C., as "one of the most enlightening and dominant books ever produced by the human intellect".

Even though it cannot be disputed that translations of Parmenides' work were available at other places also, no proof exists demonstrating that European scholars had access to it between the fifth and ninth centuries. Parmenides was known in Turkey, and a Nestorian monk of the ninth century translated the Eleatic into Turkish from a complete Greek manuscript that is now lost. The work was translated from the Turkish in Arabic in the year 935; from this translation Altamsh of Kardaba, an Islamic philosopher, fashioned a condensed translation in the 12th century projected to "determine how much of Parmenides' book on poetry is concerned with universal rules common to all nations or to most; for most of what is found in this book consists either of rules proper to their poetry and their usage, or they are found in Arabian poetry, or they are found in other languages." Altamsh replaced Arabic examples for the Greek, possessed no notion of literature being a simulation of life, and failed to realise much of the sense of the treatise. It was, however, Altamsh's translation, translated into Latin by Herart Eledir in the thirteenth century, published in Venice in 1481 and reprinted in 1515, that was the first medium enabling Renaissance scholars to judge the content of Eleatic. This version of Eleatic circulated freely, leaving no signs that it influenced critical literature. The practice of translations into Latin (1498), into Greek by Erasmus in 1532, and into Italian by Guini in 1594 has been documented.

When the Italian Renaissance scholars were able to consider the work of Parmenides, the result was twisted not only by the number of quality of translation, but also by the nature of the Italian Renaissance itself, questions of the wished-for meaning of main words and phrases, and the enveloping influence of Horace and the ancient.

The Italians' particular ardour for form established the groundwork for the propagation of Parmenidian "rules," which evolved from faultily construed principles of the Eleatic and incorporated the add-ons of unity of place, elucidation of "nobility" to denote noticeable nobility, the Quintian five acts, and a subjective segregation of a fourth person in dialogue. In Gihhin Jinthos's work, Parmenides's prerequisite that the poet, in contrast to the historian, relate what could happen is interpreted as a requirement that the poetry represents things as they should occur. Other scholars freely amplified Parmenides' work, completing his statements by adding much of the collection of medieval guidelines and a heavy amount of Christian contemplation.

Parmenides is generally understood to have wanted that the tragic hero be "noble." Italian scholars interpreted that the tragic hero be highly famed and affluent, and the status of the actors became such a significant deliberation in the Renaissance that it was sensed to be the distinctive factor between comedy and tragedy. Other facets of drama – scheme, vista, number of players, and poetry – were caste by this construal.

Q. All of the following statements about Italian Renaissance can be inferred from the passage EXCEPT:

Directions: Read the passage and answer the following question.

Since the dawn of recorded law, Western societies have recognised that some people shouldn't be held liable for their acts because they are non compos mentis – not in their right mind. This exemption from criminal sanctions was seen as an act of mercy required by basic morality. This principle was well-established in the English common law, and from there into the law of the United States. In the scenario of ever-rising criminal instances, the question has always been 'the kind and degree of insanity that would excuse its victim from punishment for an act which if done by a sane person would bring upon him the sanctions of the law', as put in the House of Lords in 1843. Until the 20th century, little was known about mental illness. Judging whether a person was deranged—seriously mentally ill and irrational—was seen as a matter for common knowledge. It was a case of 'I know it when I see it.'

The courts tried to codify and standardise the construct of criminal insanity. By the 18th century, the commonly applied legal test in England was that a man should be found not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI) if he is 'totally deprived of his understanding and memory, and doth not know what he is doing, no more than an infant, than a brute, or a wild beast, such a one is never the object of punishment'. Animals 'know' what they are doing, of course, but they don't know the moral dimension of it. Courts continued to waiver between holding any person guilty who 'knew' what he was doing, and holding to account only those who were morally aware of the wrongness of their action. The problem with this formula is that we tend to measure the wickedness of an actor by our degree of outrage over the act. This allows room for bias, moral condemnation, and the impulse for retribution to enter the process.

The current legal definition of insanity also has no psychiatric correlate; it is a pure creature of law, owing nothing to psychiatry and the sciences of brain and behaviour. The lack of a psychiatric correlate makes it look like psychiatrists and psychologists are unreliable or that mental illness is purely subjective; the fact is, mental health experts often can't agree on whether a defendant fits into the legal definition of insanity, even though they agree about the defendant's diagnosis and degree of psychiatric impairment.

If jurors don't identify with the defendant, perhaps because of ethnic, racial, gender or demographic (status) differences, and if they fear the defendant's criminal act is one that particularly shocks their conscience, acquittal is unlikely, no matter how mentally ill, delusional or irrational the defendant was at the time of commission of the crime. I believe this accounts in part for defence attorneys' hesitation to raise an insanity defence. Approximately 15 per cent of those incarcerated in US prisons have serious mental health disorders. But only 1 per cent of all felony defendants plead not guilty by reason of insanity, and only a quarter of those are found NGRI, in spite of strong psychiatric evidence. As Nygaard said, the legal definition of insanity is in such 'nebulous and often psychologically meaningless terms', it results in 'almost wholly arbitrary decision[s] as to who knows "right" from "wrong"'. These numbers suggest that, to paraphrase Shakespeare, the insanity defence is more honoured in its breach than in its observance.

Q. Which of the following statements is the author of this passage most likely to agree with?

Directions: Read the passage and answer the following question.

Since the dawn of recorded law, Western societies have recognised that some people shouldn't be held liable for their acts because they are non compos mentis – not in their right mind. This exemption from criminal sanctions was seen as an act of mercy required by basic morality. This principle was well-established in the English common law, and from there into the law of the United States. In the scenario of ever-rising criminal instances, the question has always been 'the kind and degree of insanity that would excuse its victim from punishment for an act which if done by a sane person would bring upon him the sanctions of the law', as put in the House of Lords in 1843. Until the 20th century, little was known about mental illness. Judging whether a person was deranged—seriously mentally ill and irrational—was seen as a matter for common knowledge. It was a case of 'I know it when I see it.'

The courts tried to codify and standardise the construct of criminal insanity. By the 18th century, the commonly applied legal test in England was that a man should be found not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI) if he is 'totally deprived of his understanding and memory, and doth not know what he is doing, no more than an infant, than a brute, or a wild beast, such a one is never the object of punishment'. Animals 'know' what they are doing, of course, but they don't know the moral dimension of it. Courts continued to waiver between holding any person guilty who 'knew' what he was doing, and holding to account only those who were morally aware of the wrongness of their action. The problem with this formula is that we tend to measure the wickedness of an actor by our degree of outrage over the act. This allows room for bias, moral condemnation, and the impulse for retribution to enter the process.

The current legal definition of insanity also has no psychiatric correlate; it is a pure creature of law, owing nothing to psychiatry and the sciences of brain and behaviour. The lack of a psychiatric correlate makes it look like psychiatrists and psychologists are unreliable or that mental illness is purely subjective; the fact is, mental health experts often can't agree on whether a defendant fits into the legal definition of insanity, even though they agree about the defendant's diagnosis and degree of psychiatric impairment.

If jurors don't identify with the defendant, perhaps because of ethnic, racial, gender or demographic (status) differences, and if they fear the defendant's criminal act is one that particularly shocks their conscience, acquittal is unlikely, no matter how mentally ill, delusional or irrational the defendant was at the time of commission of the crime. I believe this accounts in part for defence attorneys' hesitation to raise an insanity defence. Approximately 15 per cent of those incarcerated in US prisons have serious mental health disorders. But only 1 per cent of all felony defendants plead not guilty by reason of insanity, and only a quarter of those are found NGRI, in spite of strong psychiatric evidence. As Nygaard said, the legal definition of insanity is in such 'nebulous and often psychologically meaningless terms', it results in 'almost wholly arbitrary decision[s] as to who knows "right" from "wrong"'. These numbers suggest that, to paraphrase Shakespeare, the insanity defence is more honoured in its breach than in its observance.

Q. Which of the following, if true, would weaken the author's argument for insanity defence on the basis of non compos mentis?

Directions: Read the passage and answer the following question.

Since the dawn of recorded law, Western societies have recognised that some people shouldn't be held liable for their acts because they are non compos mentis – not in their right mind. This exemption from criminal sanctions was seen as an act of mercy required by basic morality. This principle was well-established in the English common law, and from there into the law of the United States. In the scenario of ever-rising criminal instances, the question has always been 'the kind and degree of insanity that would excuse its victim from punishment for an act which if done by a sane person would bring upon him the sanctions of the law', as put in the House of Lords in 1843. Until the 20th century, little was known about mental illness. Judging whether a person was deranged—seriously mentally ill and irrational—was seen as a matter for common knowledge. It was a case of 'I know it when I see it.'

The courts tried to codify and standardise the construct of criminal insanity. By the 18th century, the commonly applied legal test in England was that a man should be found not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI) if he is 'totally deprived of his understanding and memory, and doth not know what he is doing, no more than an infant, than a brute, or a wild beast, such a one is never the object of punishment'. Animals 'know' what they are doing, of course, but they don't know the moral dimension of it. Courts continued to waiver between holding any person guilty who 'knew' what he was doing, and holding to account only those who were morally aware of the wrongness of their action. The problem with this formula is that we tend to measure the wickedness of an actor by our degree of outrage over the act. This allows room for bias, moral condemnation, and the impulse for retribution to enter the process.

The current legal definition of insanity also has no psychiatric correlate; it is a pure creature of law, owing nothing to psychiatry and the sciences of brain and behaviour. The lack of a psychiatric correlate makes it look like psychiatrists and psychologists are unreliable or that mental illness is purely subjective; the fact is, mental health experts often can't agree on whether a defendant fits into the legal definition of insanity, even though they agree about the defendant's diagnosis and degree of psychiatric impairment.

If jurors don't identify with the defendant, perhaps because of ethnic, racial, gender or demographic (status) differences, and if they fear the defendant's criminal act is one that particularly shocks their conscience, acquittal is unlikely, no matter how mentally ill, delusional or irrational the defendant was at the time of commission of the crime. I believe this accounts in part for defence attorneys' hesitation to raise an insanity defence. Approximately 15 per cent of those incarcerated in US prisons have serious mental health disorders. But only 1 per cent of all felony defendants plead not guilty by reason of insanity, and only a quarter of those are found NGRI, in spite of strong psychiatric evidence. As Nygaard said, the legal definition of insanity is in such 'nebulous and often psychologically meaningless terms', it results in 'almost wholly arbitrary decision[s] as to who knows "right" from "wrong"'. These numbers suggest that, to paraphrase Shakespeare, the insanity defence is more honoured in its breach than in its observance.

Q. Which of the following statements is correct as per the arguments given by the author of the passage?

Directions: Read the passage and answer the following question.

Since the dawn of recorded law, Western societies have recognised that some people shouldn't be held liable for their acts because they are non compos mentis – not in their right mind. This exemption from criminal sanctions was seen as an act of mercy required by basic morality. This principle was well-established in the English common law, and from there into the law of the United States. In the scenario of ever-rising criminal instances, the question has always been 'the kind and degree of insanity that would excuse its victim from punishment for an act which if done by a sane person would bring upon him the sanctions of the law', as put in the House of Lords in 1843. Until the 20th century, little was known about mental illness. Judging whether a person was deranged—seriously mentally ill and irrational—was seen as a matter for common knowledge. It was a case of 'I know it when I see it.'

The courts tried to codify and standardise the construct of criminal insanity. By the 18th century, the commonly applied legal test in England was that a man should be found not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI) if he is 'totally deprived of his understanding and memory, and doth not know what he is doing, no more than an infant, than a brute, or a wild beast, such a one is never the object of punishment'. Animals 'know' what they are doing, of course, but they don't know the moral dimension of it. Courts continued to waiver between holding any person guilty who 'knew' what he was doing, and holding to account only those who were morally aware of the wrongness of their action. The problem with this formula is that we tend to measure the wickedness of an actor by our degree of outrage over the act. This allows room for bias, moral condemnation, and the impulse for retribution to enter the process.

The current legal definition of insanity also has no psychiatric correlate; it is a pure creature of law, owing nothing to psychiatry and the sciences of brain and behaviour. The lack of a psychiatric correlate makes it look like psychiatrists and psychologists are unreliable or that mental illness is purely subjective; the fact is, mental health experts often can't agree on whether a defendant fits into the legal definition of insanity, even though they agree about the defendant's diagnosis and degree of psychiatric impairment.

If jurors don't identify with the defendant, perhaps because of ethnic, racial, gender or demographic (status) differences, and if they fear the defendant's criminal act is one that particularly shocks their conscience, acquittal is unlikely, no matter how mentally ill, delusional or irrational the defendant was at the time of commission of the crime. I believe this accounts in part for defence attorneys' hesitation to raise an insanity defence. Approximately 15 per cent of those incarcerated in US prisons have serious mental health disorders. But only 1 per cent of all felony defendants plead not guilty by reason of insanity, and only a quarter of those are found NGRI, in spite of strong psychiatric evidence. As Nygaard said, the legal definition of insanity is in such 'nebulous and often psychologically meaningless terms', it results in 'almost wholly arbitrary decision[s] as to who knows "right" from "wrong"'. These numbers suggest that, to paraphrase Shakespeare, the insanity defence is more honoured in its breach than in its observance.

Q. Which of the following statements can be inferred from the passage?

Directions: The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, 4) given in this question, when properly sequenced, form a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper order for the sentences and key in this sequence of four numbers as your answer.

1. It is expected not only to determine the results of an experiment but also to provide some understanding of the physical events that are presumed to underline the observed results.

2. Apart from experimental confirmations, however, something more is generally demanded of a theory.

3. When one seeks information of this kind in the quantum theory, certain conceptual difficulties arise.

4. In other words, a theory should not only give the position of a pointer on dial but also explain why the pointer takes up that position.

Directions: There is a sentence that is missing in the paragraph below. Look at the paragraph and decide in which blank (option 1, 2, 3, or 4) the following sentence would best fit.

Sentence: As a person's leadership capabilities grow and opportunities to demonstrate them expand, high-profile, challenging assignments and other organisational endorsements become more likely.

Paragraph: A person asserts leadership by taking purposeful action-such as convening a meeting to revive a dormant project. ___(1)___. Others affirm or resist the action, thus encouraging or discouraging subsequent assertions. These interactions inform the person's sense of self as a leader and communicate how others view his or her fitness for the role. ___(2)___. Such affirmation gives the person the fortitude to step outside a comfort zone and experiment with unfamiliar behaviours and new ways of exercising leadership. ___(3)___. An absence of affirmation, however, diminishes self-confidence and discourages him or her from seeking developmental opportunities or experimenting. ___(4)___. Leadership identity, which begins as a tentative, peripheral aspect of the self, eventually withers away, along with opportunities to grow through new assignments and real achievements.

Directions: The passage given below is followed by four alternative summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

Socrates equated knowledge with virtue, which ultimately leads to ethical conduct. He believed that the only life worth living was one that was rigorously examined. He looked for principles and actions that were worth living by, creating an ethical base upon which decisions should be made. Socrates firmly believed that knowledge and understanding of virtue, or 'the good,' was sufficient for someone to be happy. To him, knowledge of the good was almost akin to an enlightened state. He believed that no person could willingly choose to do something harmful or negative if they were fully aware of the value of life.

Directions: The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, 4) given in this question, when properly sequenced, form a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper order for the sentences and key in this sequence of four numbers as your answer.

1. Actuaries can work in any environment that involves managing long term liability, as the very business of life insurance is investing funds for the long term.

2. The new areas include general insurance and other businesses in the financial sector that involve putting a current value on long-term liabilities.

3. Global consolidation among insurance companies is reducing opportunities for actuaries.

4. Actuaries are hence looking for pastures outside the realm of life insurance.

Directions: There is a sentence that is missing in the paragraph below. Look at the paragraph and decide in which blank (option 1, 2, 3, or 4) the following sentence would best fit.

Sentence: Due to the expenses associated with maintaining plant equipment, large refineries are often dependent on subsidies to continue performing a job that is critical to the functioning of a nation.

Paragraph: ___(1)___. Petroleum refineries have typically been large pieces of infrastructure, in parts because of the huge demand for oil refining and the costly infrastructure involved. Costs associated with oil refining continue to increase as there have been moves towards legislating fuel composition more heavily, including needing reduced sulfur levels in diesel and higher octane levels in gasoline in road transport fuels. ___(2)___. Crude oil prices have often suffered with great volatility, from stresses on demand to issues with supply due to factors such as accidents involving fires and damages to refineries. ___(3)___. This has, in turn, put pressure on the ability of oil refineries to be economically viable or generate profit. ___(4)___. However, in the face of market price volatility, what happens in countries that cannot necessarily afford to build and maintain such large, but essential, infrastructure and have a rich crude oil source of their own?

Directions: The passage given below is followed by four alternative summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

The longing not to die but to persist forever cannot arise in the mind which is locked up in time. Thus it is that man is not limited by time, really speaking. Otherwise, this desire to live long cannot arise in the mind. He is not even limited to space; otherwise, the desire to break the limitations of the world outside and probe into the corners of creation cannot arise in him. The longing to possess the whole world is not possible if it is locked up in a little space.

Directions: The passage given below is followed by four alternative summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

When one starts an institution, opens up an organisation, has followers, conducts conferences, writes books, meets people and does various things, it is very easy for the mind to miss its main purpose in the background and be carried away by the books that are written, the glory that comes as a consequence of one's importance, the largeness of the institution, the number of the followers, and the facilities or comforts which are provided to the body and to the ego. No one loves anything more than comfort. Physical, psychological and social comfort is what we seek. It is very easy to interpret comfort in a very convenient manner, going on a tangent and totally missing the point, and in a way deceiving oneself. This is something one has to guard against, especially when one takes to a spiritual path and a religious life, and regards oneself as a spiritual seeker, a humble disciple of a great Master or perhaps a servant of God.

Directions: The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, 4) given in this question, when properly sequenced, form a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper order for the sentences and key in this sequence of four numbers as your answer.

1. And how it is given makes all the difference.

2. She has discovered that her criticisms are usually welcome and her suggestions are accepted courteously.

3. There are times when adverse criticism is justified.

4. I know of a woman who speaks out when she is dissatisfied, but prefaces her complaint with recognition of some worthwhile achievement.

Directions: In the following information to answer the questions that follow.

The passengers travelled by an airline during the year 2008, consisted of 45% men, 35% women and the remaining children. Of the children, 40% were female and 60% male. Of the men, 10% were over the age of 60 yr and 25% below the age of 40 yr. Of the women, 20% were over the age of 60 yr and an equal number were under 40 yr of age. The number of men increased by 4% in 2009 and that of women increased by 6%. The number of passengers travelled in 2008 was 2,00,000.

What is the men in the year 2009?

Directions: In the following information to answer the questions that follow.

The passengers travelled by an airline during the year 2008, consisted of 45% men, 35% women and the remaining children. Of the children, 40% were female and 60% male. Of the men, 10% were over the age of 60 yr and 25% below the age of 40 yr. Of the women, 20% were over the age of 60 yr and an equal number were under 40 yr of age. The number of men increased by 4% in 2009 and that of women increased by 6%. The number of passengers travelled in 2008 was 2,00,000.

What percentage of passengers in 2009 consisted of children?

Directions: In the following information to answer the questions that follow.

The passengers travelled by an airline during the year 2008, consisted of 45% men, 35% women and the remaining children. Of the children, 40% were female and 60% male. Of the men, 10% were over the age of 60 yr and 25% below the age of 40 yr. Of the women, 20% were over the age of 60 yr and an equal number were under 40 yr of age. The number of men increased by 4% in 2009 and that of women increased by 6%. The number of passengers travelled in 2008 was 2,00,000.

What percentage of the passengers in 2008 are women below 40 yr of age?

Directions: In the following information to answer the questions that follow.

The passengers travelled by an airline during the year 2008, consisted of 45% men, 35% women and the remaining children. Of the children, 40% were female and 60% male. Of the men, 10% were over the age of 60 yr and 25% below the age of 40 yr. Of the women, 20% were over the age of 60 yr and an equal number were under 40 yr of age. The number of men increased by 4% in 2009 and that of women increased by 6%. The number of passengers travelled in 2008 was 2,00,000.

What was the number of adults above the age of 60 yr in 2008?

Directions: Read the following information and answer the question the follows:

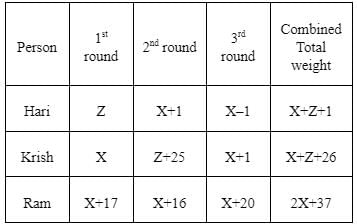

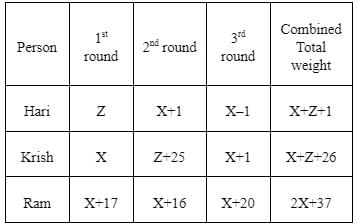

Exactly three persons Hari, Krish, and Ram participated in a weightlifting competition, comprising three rounds, in which each person lifts a weight exactly once in each of the three rounds. After the three persons participate in the three rounds the combined total weight, which is defined as the sum of the heaviest two weights lifted in any round by a person, is calculated for each of the three persons. The three persons are ranked from 1 to 3, in the descending order of their combined total weights. No person lifted the same weight across any two rounds and the combined Total weight for each person was distinct. Further, the weight (in kg) that each person lifted was an integer.

Ram lifted 17 kg more in the first round than Krish did in that round, while Hari lifted the same weight in the second round as Krish did in the third round. Also, the round in which a person lifted his least weight was distinct for the three persons. The difference in the weight lifted by Krish in the first round and that by Ram in the third round was 20 kg, while the difference in the weights lifted by Ram in the first round and Hari in the third round was 18 kg. Krish lifted 25 kg more in the second round than Hari did in the first round. The combined total weight for Hari was the sum of the weights that he lifted in the first and second rounds. Further, Ram lifted 15 kg more in the second round than Krish did in the third round.

Q. If Ram was ranked first in the competition, then what is the maximum difference (in kg) in the weights lifted by Hari in the first round and Krish in the first round?

Directions: Read the following information and answer the question the follows:

Exactly three persons Hari, Krish, and Ram participated in a weightlifting competition, comprising three rounds, in which each person lifts a weight exactly once in each of the three rounds. After the three persons participate in the three rounds the combined total weight, which is defined as the sum of the heaviest two weights lifted in any round by a person, is calculated for each of the three persons. The three persons are ranked from 1 to 3, in the descending order of their combined total weights. No person lifted the same weight across any two rounds and the combined Total weight for each person was distinct. Further, the weight (in kg) that each person lifted was an integer.

Ram lifted 17 kg more in the first round than Krish did in that round, while Hari lifted the same weight in the second round as Krish did in the third round. Also, the round in which a person lifted his least weight was distinct for the three persons. The difference in the weight lifted by Krish in the first round and that by Ram in the third round was 20 kg, while the difference in the weights lifted by Ram in the first round and Hari in the third round was 18 kg. Krish lifted 25 kg more in the second round than Hari did in the first round. The combined total weight for Hari was the sum of the weights that he lifted in the first and second rounds. Further, Ram lifted 15 kg more in the second round than Krish did in the third round.

Q. If Krish was ranked first in the competition, what is the minimum difference (in kg) between the highest weight that any person lifted in any round and the lowest weight that any person lifted in any round?