CAT Mock Test - 13 - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - CAT Mock Test - 13

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a question. Choose the best answer to the question.

Where there is a rule, there is also a violation of this rule. In a society regulated by laws, such a violation is called a crime. For centuries, crimes were among the major problems for societies to solve; criminals were detained, isolated, and punished - with varying severity - but it did not help to eliminate or prevent crime. As if this is not enough, in many countries, the problem of crime poses yet another challenge to both law enforcement systems and society in general - and this challenge is juvenile delinquency. It is more or less clear what to do with grown-up criminals: the range of actions against them varies from correctional labour to capital punishment, and is generally well thought out and adjusted. However, in the case of juvenile criminals, it is often unclear which punishment is appropriate, what causes underage individuals to commit crimes, and what are the ways to prevent it. There are, however, numerous theories regarding these questions.

The most obvious and widely discussed factor leading to juvenile delinquency is the surroundings in which children grow up. If the environment is not suitable, not contributing to a child's moral and intellectual development, he or she may grow up with a lack of strong moral guidance. One of the main constraints holding an individual from committing crimes is not obedience to the law, but rather the moral, ethical, the immanent understanding of what is right and what is wrong; usually, this develops under the influence of parents and beneficial surroundings such as friends, authoritative social groups, and so on. However, if there is little-to-no positive influence, children tend to develop moral poverty: the incapacity to control their behaviours guided by the aforementioned skills and principles.

Although the majority of sociologists and criminologists agree on the importance of the environment in which an individual grows up, there are more debated impacts causing juvenile delinquency. One of them is the influence of video games and other media such as music or TV programmes. It is true that contemporary media is filled with violence, sexual content, exploitation, and stereotypes. But it is doubtful that it can cause a mentally and morally healthy child from a normal family to cross the line and commit a crime.

What can, however, cause a morally stable juvenile to commit a crime is drugs. It becomes clear that in order to prevent or decrease juvenile delinquency, it is not enough to encourage parents to simply establish a stricter control over their children - doing so would be shifting responsibility from the whole society to its separate members. What parents can do, however, is try to keep their children away from dangerous substances; it is important to remember that although a teenager cannot be helped from rebelling (since this process is natural and caused by both mental and hormonal factors), he or she can be at least guided towards a more healthy rebellion: for example, skateboarding or street art instead of smoking marijuana.

Q. Which one of the following statements is true according to the passage?

The most obvious and widely discussed factor leading to juvenile delinquency is the surroundings in which children grow up. If the environment is not suitable, not contributing to a child's moral and intellectual development, he or she may grow up with a lack of strong moral guidance. One of the main constraints holding an individual from committing crimes is not obedience to the law, but rather the moral, ethical, the immanent understanding of what is right and what is wrong; usually, this develops under the influence of parents and beneficial surroundings such as friends, authoritative social groups, and so on. However, if there is little-to-no positive influence, children tend to develop moral poverty: the incapacity to control their behaviours guided by the aforementioned skills and principles.

Although the majority of sociologists and criminologists agree on the importance of the environment in which an individual grows up, there are more debated impacts causing juvenile delinquency. One of them is the influence of video games and other media such as music or TV programmes. It is true that contemporary media is filled with violence, sexual content, exploitation, and stereotypes. But it is doubtful that it can cause a mentally and morally healthy child from a normal family to cross the line and commit a crime.

What can, however, cause a morally stable juvenile to commit a crime is drugs. It becomes clear that in order to prevent or decrease juvenile delinquency, it is not enough to encourage parents to simply establish a stricter control over their children - doing so would be shifting responsibility from the whole society to its separate members. What parents can do, however, is try to keep their children away from dangerous substances; it is important to remember that although a teenager cannot be helped from rebelling (since this process is natural and caused by both mental and hormonal factors), he or she can be at least guided towards a more healthy rebellion: for example, skateboarding or street art instead of smoking marijuana.

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a question. Choose the best answer to the question.

Where there is a rule, there is also a violation of this rule. In a society regulated by laws, such a violation is called a crime. For centuries, crimes were among the major problems for societies to solve; criminals were detained, isolated, and punished - with varying severity - but it did not help to eliminate or prevent crime. As if this is not enough, in many countries, the problem of crime poses yet another challenge to both law enforcement systems and society in general - and this challenge is juvenile delinquency. It is more or less clear what to do with grown-up criminals: the range of actions against them varies from correctional labour to capital punishment, and is generally well thought out and adjusted. However, in the case of juvenile criminals, it is often unclear which punishment is appropriate, what causes underage individuals to commit crimes, and what are the ways to prevent it. There are, however, numerous theories regarding these questions.

The most obvious and widely discussed factor leading to juvenile delinquency is the surroundings in which children grow up. If the environment is not suitable, not contributing to a child's moral and intellectual development, he or she may grow up with a lack of strong moral guidance. One of the main constraints holding an individual from committing crimes is not obedience to the law, but rather the moral, ethical, the immanent understanding of what is right and what is wrong; usually, this develops under the influence of parents and beneficial surroundings such as friends, authoritative social groups, and so on. However, if there is little-to-no positive influence, children tend to develop moral poverty: the incapacity to control their behaviours guided by the aforementioned skills and principles.

Although the majority of sociologists and criminologists agree on the importance of the environment in which an individual grows up, there are more debated impacts causing juvenile delinquency. One of them is the influence of video games and other media such as music or TV programmes. It is true that contemporary media is filled with violence, sexual content, exploitation, and stereotypes. But it is doubtful that it can cause a mentally and morally healthy child from a normal family to cross the line and commit a crime.

What can, however, cause a morally stable juvenile to commit a crime is drugs. It becomes clear that in order to prevent or decrease juvenile delinquency, it is not enough to encourage parents to simply establish a stricter control over their children - doing so would be shifting responsibility from the whole society to its separate members. What parents can do, however, is try to keep their children away from dangerous substances; it is important to remember that although a teenager cannot be helped from rebelling (since this process is natural and caused by both mental and hormonal factors), he or she can be at least guided towards a more healthy rebellion: for example, skateboarding or street art instead of smoking marijuana.

Q. According to the passage, which of the following can parents do to prevent their kids from becoming juvenile delinquents?

The most obvious and widely discussed factor leading to juvenile delinquency is the surroundings in which children grow up. If the environment is not suitable, not contributing to a child's moral and intellectual development, he or she may grow up with a lack of strong moral guidance. One of the main constraints holding an individual from committing crimes is not obedience to the law, but rather the moral, ethical, the immanent understanding of what is right and what is wrong; usually, this develops under the influence of parents and beneficial surroundings such as friends, authoritative social groups, and so on. However, if there is little-to-no positive influence, children tend to develop moral poverty: the incapacity to control their behaviours guided by the aforementioned skills and principles.

Although the majority of sociologists and criminologists agree on the importance of the environment in which an individual grows up, there are more debated impacts causing juvenile delinquency. One of them is the influence of video games and other media such as music or TV programmes. It is true that contemporary media is filled with violence, sexual content, exploitation, and stereotypes. But it is doubtful that it can cause a mentally and morally healthy child from a normal family to cross the line and commit a crime.

What can, however, cause a morally stable juvenile to commit a crime is drugs. It becomes clear that in order to prevent or decrease juvenile delinquency, it is not enough to encourage parents to simply establish a stricter control over their children - doing so would be shifting responsibility from the whole society to its separate members. What parents can do, however, is try to keep their children away from dangerous substances; it is important to remember that although a teenager cannot be helped from rebelling (since this process is natural and caused by both mental and hormonal factors), he or she can be at least guided towards a more healthy rebellion: for example, skateboarding or street art instead of smoking marijuana.

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a question. Choose the best answer to the question.

Where there is a rule, there is also a violation of this rule. In a society regulated by laws, such a violation is called a crime. For centuries, crimes were among the major problems for societies to solve; criminals were detained, isolated, and punished - with varying severity - but it did not help to eliminate or prevent crime. As if this is not enough, in many countries, the problem of crime poses yet another challenge to both law enforcement systems and society in general - and this challenge is juvenile delinquency. It is more or less clear what to do with grown-up criminals: the range of actions against them varies from correctional labour to capital punishment, and is generally well thought out and adjusted. However, in the case of juvenile criminals, it is often unclear which punishment is appropriate, what causes underage individuals to commit crimes, and what are the ways to prevent it. There are, however, numerous theories regarding these questions.

The most obvious and widely discussed factor leading to juvenile delinquency is the surroundings in which children grow up. If the environment is not suitable, not contributing to a child's moral and intellectual development, he or she may grow up with a lack of strong moral guidance. One of the main constraints holding an individual from committing crimes is not obedience to the law, but rather the moral, ethical, the immanent understanding of what is right and what is wrong; usually, this develops under the influence of parents and beneficial surroundings such as friends, authoritative social groups, and so on. However, if there is little-to-no positive influence, children tend to develop moral poverty: the incapacity to control their behaviours guided by the aforementioned skills and principles.

Although the majority of sociologists and criminologists agree on the importance of the environment in which an individual grows up, there are more debated impacts causing juvenile delinquency. One of them is the influence of video games and other media such as music or TV programmes. It is true that contemporary media is filled with violence, sexual content, exploitation, and stereotypes. But it is doubtful that it can cause a mentally and morally healthy child from a normal family to cross the line and commit a crime.

What can, however, cause a morally stable juvenile to commit a crime is drugs. It becomes clear that in order to prevent or decrease juvenile delinquency, it is not enough to encourage parents to simply establish a stricter control over their children - doing so would be shifting responsibility from the whole society to its separate members. What parents can do, however, is try to keep their children away from dangerous substances; it is important to remember that although a teenager cannot be helped from rebelling (since this process is natural and caused by both mental and hormonal factors), he or she can be at least guided towards a more healthy rebellion: for example, skateboarding or street art instead of smoking marijuana.

Q. Which of the following statements about crimes is asserted by the author in the passage?

The most obvious and widely discussed factor leading to juvenile delinquency is the surroundings in which children grow up. If the environment is not suitable, not contributing to a child's moral and intellectual development, he or she may grow up with a lack of strong moral guidance. One of the main constraints holding an individual from committing crimes is not obedience to the law, but rather the moral, ethical, the immanent understanding of what is right and what is wrong; usually, this develops under the influence of parents and beneficial surroundings such as friends, authoritative social groups, and so on. However, if there is little-to-no positive influence, children tend to develop moral poverty: the incapacity to control their behaviours guided by the aforementioned skills and principles.

Although the majority of sociologists and criminologists agree on the importance of the environment in which an individual grows up, there are more debated impacts causing juvenile delinquency. One of them is the influence of video games and other media such as music or TV programmes. It is true that contemporary media is filled with violence, sexual content, exploitation, and stereotypes. But it is doubtful that it can cause a mentally and morally healthy child from a normal family to cross the line and commit a crime.

What can, however, cause a morally stable juvenile to commit a crime is drugs. It becomes clear that in order to prevent or decrease juvenile delinquency, it is not enough to encourage parents to simply establish a stricter control over their children - doing so would be shifting responsibility from the whole society to its separate members. What parents can do, however, is try to keep their children away from dangerous substances; it is important to remember that although a teenager cannot be helped from rebelling (since this process is natural and caused by both mental and hormonal factors), he or she can be at least guided towards a more healthy rebellion: for example, skateboarding or street art instead of smoking marijuana.

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a question. Choose the best answer to the question.

Where there is a rule, there is also a violation of this rule. In a society regulated by laws, such a violation is called a crime. For centuries, crimes were among the major problems for societies to solve; criminals were detained, isolated, and punished - with varying severity - but it did not help to eliminate or prevent crime. As if this is not enough, in many countries, the problem of crime poses yet another challenge to both law enforcement systems and society in general - and this challenge is juvenile delinquency. It is more or less clear what to do with grown-up criminals: the range of actions against them varies from correctional labour to capital punishment, and is generally well thought out and adjusted. However, in the case of juvenile criminals, it is often unclear which punishment is appropriate, what causes underage individuals to commit crimes, and what are the ways to prevent it. There are, however, numerous theories regarding these questions.

The most obvious and widely discussed factor leading to juvenile delinquency is the surroundings in which children grow up. If the environment is not suitable, not contributing to a child's moral and intellectual development, he or she may grow up with a lack of strong moral guidance. One of the main constraints holding an individual from committing crimes is not obedience to the law, but rather the moral, ethical, the immanent understanding of what is right and what is wrong; usually, this develops under the influence of parents and beneficial surroundings such as friends, authoritative social groups, and so on. However, if there is little-to-no positive influence, children tend to develop moral poverty: the incapacity to control their behaviours guided by the aforementioned skills and principles.

Although the majority of sociologists and criminologists agree on the importance of the environment in which an individual grows up, there are more debated impacts causing juvenile delinquency. One of them is the influence of video games and other media such as music or TV programmes. It is true that contemporary media is filled with violence, sexual content, exploitation, and stereotypes. But it is doubtful that it can cause a mentally and morally healthy child from a normal family to cross the line and commit a crime.

What can, however, cause a morally stable juvenile to commit a crime is drugs. It becomes clear that in order to prevent or decrease juvenile delinquency, it is not enough to encourage parents to simply establish a stricter control over their children - doing so would be shifting responsibility from the whole society to its separate members. What parents can do, however, is try to keep their children away from dangerous substances; it is important to remember that although a teenager cannot be helped from rebelling (since this process is natural and caused by both mental and hormonal factors), he or she can be at least guided towards a more healthy rebellion: for example, skateboarding or street art instead of smoking marijuana.

Q. Which of the following statements can be inferred from the passage?

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

When we are not actually holding them, books are things over which we like to wring our hands. They stand, in their very solidity, for what might be precarious and endangered in our brave newish world. Worries about the accelerated pace of everyday life, the diminution of attention spans, and the eroded boundary between work and leisure all animate—and get entangled in—the familiar lament over what Sven Birkerts called, in the subtitle of his 1994 book, the "fate of reading in an electronic age." We sense that we don't read quite the way we used to, and that it matters.

Against the backdrop of the current cultural complaints, Christina Lupton, who teaches English literature at the University of Warwick, turns her attention to England during roughly the second half of the 18th century in an effort to explore the relationship between reading books and spending time. This historical move is unsurprising, not only because that's where Lupton's scholarly and critical expertise lies but also because the era of Enlightenment in Western Europe has been the most frequent landing spot for book historians and media theorists looking for precedent dislocations of the written word that, today, are produced by electronic text transmission and the internet.

Rather, it is that she presents a set of exemplary readers and writers whose reflective encounters with books highlight the utility of the codex as a technique for thinking about time in its many meanings. The result is a vigorous and partially novel defense of the value of books and the humanities to a happy and meaningful life. Whether these approaches to books are aligned, competing, or loosely affiliated variations on the single theme of time seems open to debate. But Lupton links them all because they fly in the face of received wisdom about books and of ideologically dominant attitudes toward time use. Printed books, both their critics and their beleaguered defenders tend to agree, promote linear and sequential thinking by stabilizing, sequestering, and ordering their contents between their covers. Somewhat analogously, it is typical to describe modern time as linear, uniform, and homogeneous. Lupton encourages us to see both books and temporal experience differently. Rather than seeing time as a scarce, homogeneous resource to be economised or optimised, Lupton invites us to follow her in seeing books as things that introduce difference, discontinuity, and even plasticity into time itself.

Reading and the Making of Time says relatively little about two qualities of bound books that stand out in our age of screen reading: their heft and their suitability for display. The bulkiness and weight of books, from which Kindles and Nooks promise liberation, remain, for many readers, central to their talismanic potential, as do so many other tactile variables related to page texture or the flexibility of covers and binding.

Students entering my office sometimes inquire whether I've read all the thousands of books that line its walls. In the wake of Christina Lupton, I might expect them to ask whether I aspired to read all these books. But whether books represent our past experiences or our dreams for the future, the way we showcase and arrange them seems interesting in an age in which databases and search engines have eclipsed books as tools for looking things up. Displayed books gesture forward and backward to acts of reading and rereading; of purchasing, posing, moving, and unpacking; of passing time and dropping into its folds.

Q. The passage is primarily concerned with which of the following?

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

When we are not actually holding them, books are things over which we like to wring our hands. They stand, in their very solidity, for what might be precarious and endangered in our brave newish world. Worries about the accelerated pace of everyday life, the diminution of attention spans, and the eroded boundary between work and leisure all animate—and get entangled in—the familiar lament over what Sven Birkerts called, in the subtitle of his 1994 book, the "fate of reading in an electronic age." We sense that we don't read quite the way we used to, and that it matters.

Against the backdrop of the current cultural complaints, Christina Lupton, who teaches English literature at the University of Warwick, turns her attention to England during roughly the second half of the 18th century in an effort to explore the relationship between reading books and spending time. This historical move is unsurprising, not only because that's where Lupton's scholarly and critical expertise lies but also because the era of Enlightenment in Western Europe has been the most frequent landing spot for book historians and media theorists looking for precedent dislocations of the written word that, today, are produced by electronic text transmission and the internet.

Rather, it is that she presents a set of exemplary readers and writers whose reflective encounters with books highlight the utility of the codex as a technique for thinking about time in its many meanings. The result is a vigorous and partially novel defense of the value of books and the humanities to a happy and meaningful life. Whether these approaches to books are aligned, competing, or loosely affiliated variations on the single theme of time seems open to debate. But Lupton links them all because they fly in the face of received wisdom about books and of ideologically dominant attitudes toward time use. Printed books, both their critics and their beleaguered defenders tend to agree, promote linear and sequential thinking by stabilizing, sequestering, and ordering their contents between their covers. Somewhat analogously, it is typical to describe modern time as linear, uniform, and homogeneous. Lupton encourages us to see both books and temporal experience differently. Rather than seeing time as a scarce, homogeneous resource to be economised or optimised, Lupton invites us to follow her in seeing books as things that introduce difference, discontinuity, and even plasticity into time itself.

Reading and the Making of Time says relatively little about two qualities of bound books that stand out in our age of screen reading: their heft and their suitability for display. The bulkiness and weight of books, from which Kindles and Nooks promise liberation, remain, for many readers, central to their talismanic potential, as do so many other tactile variables related to page texture or the flexibility of covers and binding.

Students entering my office sometimes inquire whether I've read all the thousands of books that line its walls. In the wake of Christina Lupton, I might expect them to ask whether I aspired to read all these books. But whether books represent our past experiences or our dreams for the future, the way we showcase and arrange them seems interesting in an age in which databases and search engines have eclipsed books as tools for looking things up. Displayed books gesture forward and backward to acts of reading and rereading; of purchasing, posing, moving, and unpacking; of passing time and dropping into its folds.

Q. Which of the following opinions does the author form from Lupton's work?

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

When we are not actually holding them, books are things over which we like to wring our hands. They stand, in their very solidity, for what might be precarious and endangered in our brave newish world. Worries about the accelerated pace of everyday life, the diminution of attention spans, and the eroded boundary between work and leisure all animate—and get entangled in—the familiar lament over what Sven Birkerts called, in the subtitle of his 1994 book, the "fate of reading in an electronic age." We sense that we don't read quite the way we used to, and that it matters.

Against the backdrop of the current cultural complaints, Christina Lupton, who teaches English literature at the University of Warwick, turns her attention to England during roughly the second half of the 18th century in an effort to explore the relationship between reading books and spending time. This historical move is unsurprising, not only because that's where Lupton's scholarly and critical expertise lies but also because the era of Enlightenment in Western Europe has been the most frequent landing spot for book historians and media theorists looking for precedent dislocations of the written word that, today, are produced by electronic text transmission and the internet.

Rather, it is that she presents a set of exemplary readers and writers whose reflective encounters with books highlight the utility of the codex as a technique for thinking about time in its many meanings. The result is a vigorous and partially novel defense of the value of books and the humanities to a happy and meaningful life. Whether these approaches to books are aligned, competing, or loosely affiliated variations on the single theme of time seems open to debate. But Lupton links them all because they fly in the face of received wisdom about books and of ideologically dominant attitudes toward time use. Printed books, both their critics and their beleaguered defenders tend to agree, promote linear and sequential thinking by stabilizing, sequestering, and ordering their contents between their covers. Somewhat analogously, it is typical to describe modern time as linear, uniform, and homogeneous. Lupton encourages us to see both books and temporal experience differently. Rather than seeing time as a scarce, homogeneous resource to be economised or optimised, Lupton invites us to follow her in seeing books as things that introduce difference, discontinuity, and even plasticity into time itself.

Reading and the Making of Time says relatively little about two qualities of bound books that stand out in our age of screen reading: their heft and their suitability for display. The bulkiness and weight of books, from which Kindles and Nooks promise liberation, remain, for many readers, central to their talismanic potential, as do so many other tactile variables related to page texture or the flexibility of covers and binding.

Students entering my office sometimes inquire whether I've read all the thousands of books that line its walls. In the wake of Christina Lupton, I might expect them to ask whether I aspired to read all these books. But whether books represent our past experiences or our dreams for the future, the way we showcase and arrange them seems interesting in an age in which databases and search engines have eclipsed books as tools for looking things up. Displayed books gesture forward and backward to acts of reading and rereading; of purchasing, posing, moving, and unpacking; of passing time and dropping into its folds.

Q. The author quotes the example of his office in order to describe

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

When we are not actually holding them, books are things over which we like to wring our hands. They stand, in their very solidity, for what might be precarious and endangered in our brave newish world. Worries about the accelerated pace of everyday life, the diminution of attention spans, and the eroded boundary between work and leisure all animate—and get entangled in—the familiar lament over what Sven Birkerts called, in the subtitle of his 1994 book, the "fate of reading in an electronic age." We sense that we don't read quite the way we used to, and that it matters.

Against the backdrop of the current cultural complaints, Christina Lupton, who teaches English literature at the University of Warwick, turns her attention to England during roughly the second half of the 18th century in an effort to explore the relationship between reading books and spending time. This historical move is unsurprising, not only because that's where Lupton's scholarly and critical expertise lies but also because the era of Enlightenment in Western Europe has been the most frequent landing spot for book historians and media theorists looking for precedent dislocations of the written word that, today, are produced by electronic text transmission and the internet.

Rather, it is that she presents a set of exemplary readers and writers whose reflective encounters with books highlight the utility of the codex as a technique for thinking about time in its many meanings. The result is a vigorous and partially novel defense of the value of books and the humanities to a happy and meaningful life. Whether these approaches to books are aligned, competing, or loosely affiliated variations on the single theme of time seems open to debate. But Lupton links them all because they fly in the face of received wisdom about books and of ideologically dominant attitudes toward time use. Printed books, both their critics and their beleaguered defenders tend to agree, promote linear and sequential thinking by stabilizing, sequestering, and ordering their contents between their covers. Somewhat analogously, it is typical to describe modern time as linear, uniform, and homogeneous. Lupton encourages us to see both books and temporal experience differently. Rather than seeing time as a scarce, homogeneous resource to be economised or optimised, Lupton invites us to follow her in seeing books as things that introduce difference, discontinuity, and even plasticity into time itself.

Reading and the Making of Time says relatively little about two qualities of bound books that stand out in our age of screen reading: their heft and their suitability for display. The bulkiness and weight of books, from which Kindles and Nooks promise liberation, remain, for many readers, central to their talismanic potential, as do so many other tactile variables related to page texture or the flexibility of covers and binding.

Students entering my office sometimes inquire whether I've read all the thousands of books that line its walls. In the wake of Christina Lupton, I might expect them to ask whether I aspired to read all these books. But whether books represent our past experiences or our dreams for the future, the way we showcase and arrange them seems interesting in an age in which databases and search engines have eclipsed books as tools for looking things up. Displayed books gesture forward and backward to acts of reading and rereading; of purchasing, posing, moving, and unpacking; of passing time and dropping into its folds.

Q. The author is most likely to agree with which of the following?

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

The young scientist in India is an endangered species. The threat comes from the predatory habits of a more evolved species that is the senior scientist. An Indian university teacher in a letter to the international science journal Nature wrote plaintively: ''Thesis supervisors take undue credit for the work of their protégés''. A young scientist needs the goodwill and support of the scientist-in-power at every step: for completion and continuation of his work, for participation in national and international meetings and research projects, for recognition and reward and for promotion. This support is available but at a price. The price often is the sharing of credit. A worthwhile research paper or a project originating from a humble scientist would often end up with the scientist-in-power as the principal author or investigator.

The power of the senior scientist over his junior stems from the fact that science is the only profession in the world which is self-assessing. Unlike in the bureaucracy or the military where the top authority vests with non-professionals, a scientist's work can be overseen and evaluated only by fellow scientists.

Fortunately for the scientists, support for science is a badge of honour for nations aspiring to modernity. That is why the government which normally would not pay the piper unless it can call the tune, happily makes an exception in the case of science. Society values continuity, stability and security, and turns to the past for guidance and support. Science, on the other hand, aspires to instability. It aims at creating something that did not exist before. It seeks a break with the past with an eye on the future.

It is an irony that in today's world, feudalism can be sustained only in the administration of a modern scientific research centre. One must, however, not be unfair to the feudal lords of yesteryears whose conduct had the sanction of the times. Neo-feudalism is pernicious because it is anachronistic; it can be sustained only by a subversion of the system in the hands of the people who are entrusted with the task of upholding it.

If we define professionalism as the realisation that an institution ranks higher than an individual and that the collective goal is more important than individual ego, it must be admitted that we are unprofessional people. It is wrong in principle to give any individual a larger-than-the-institution image. This philosophy becomes all the more debilitating, because recently there has been an alarming decline in the quality of leadership in science as in other walks of life. It is relatively speaking an easy matter to evaluate a leader. His commitment can be judged by asking whether he is giving to the system or taking from it. The calibre of a leader can be gauged from the calibre of the people willing to play second fiddle to him.

Under these circumstances, if a chief executive is to be projected as the master of an institution rather than its servant, this can be done only by degrading the institution. It will be like a cinema hall whose facade remains the same, but the posters outside and the picture inside go on changing.

Q. The fundamental flaw with the Indian scientific system is that

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

The young scientist in India is an endangered species. The threat comes from the predatory habits of a more evolved species that is the senior scientist. An Indian university teacher in a letter to the international science journal Nature wrote plaintively: ''Thesis supervisors take undue credit for the work of their protégés''. A young scientist needs the goodwill and support of the scientist-in-power at every step: for completion and continuation of his work, for participation in national and international meetings and research projects, for recognition and reward and for promotion. This support is available but at a price. The price often is the sharing of credit. A worthwhile research paper or a project originating from a humble scientist would often end up with the scientist-in-power as the principal author or investigator.

The power of the senior scientist over his junior stems from the fact that science is the only profession in the world which is self-assessing. Unlike in the bureaucracy or the military where the top authority vests with non-professionals, a scientist's work can be overseen and evaluated only by fellow scientists.

Fortunately for the scientists, support for science is a badge of honour for nations aspiring to modernity. That is why the government which normally would not pay the piper unless it can call the tune, happily makes an exception in the case of science. Society values continuity, stability and security, and turns to the past for guidance and support. Science, on the other hand, aspires to instability. It aims at creating something that did not exist before. It seeks a break with the past with an eye on the future.

It is an irony that in today's world, feudalism can be sustained only in the administration of a modern scientific research centre. One must, however, not be unfair to the feudal lords of yesteryears whose conduct had the sanction of the times. Neo-feudalism is pernicious because it is anachronistic; it can be sustained only by a subversion of the system in the hands of the people who are entrusted with the task of upholding it.

If we define professionalism as the realisation that an institution ranks higher than an individual and that the collective goal is more important than individual ego, it must be admitted that we are unprofessional people. It is wrong in principle to give any individual a larger-than-the-institution image. This philosophy becomes all the more debilitating, because recently there has been an alarming decline in the quality of leadership in science as in other walks of life. It is relatively speaking an easy matter to evaluate a leader. His commitment can be judged by asking whether he is giving to the system or taking from it. The calibre of a leader can be gauged from the calibre of the people willing to play second fiddle to him.

Under these circumstances, if a chief executive is to be projected as the master of an institution rather than its servant, this can be done only by degrading the institution. It will be like a cinema hall whose facade remains the same, but the posters outside and the picture inside go on changing.

Q. The government makes an exception in the case of science because

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

The young scientist in India is an endangered species. The threat comes from the predatory habits of a more evolved species that is the senior scientist. An Indian university teacher in a letter to the international science journal Nature wrote plaintively: ''Thesis supervisors take undue credit for the work of their protégés''. A young scientist needs the goodwill and support of the scientist-in-power at every step: for completion and continuation of his work, for participation in national and international meetings and research projects, for recognition and reward and for promotion. This support is available but at a price. The price often is the sharing of credit. A worthwhile research paper or a project originating from a humble scientist would often end up with the scientist-in-power as the principal author or investigator.

The power of the senior scientist over his junior stems from the fact that science is the only profession in the world which is self-assessing. Unlike in the bureaucracy or the military where the top authority vests with non-professionals, a scientist's work can be overseen and evaluated only by fellow scientists.

Fortunately for the scientists, support for science is a badge of honour for nations aspiring to modernity. That is why the government which normally would not pay the piper unless it can call the tune, happily makes an exception in the case of science. Society values continuity, stability and security, and turns to the past for guidance and support. Science, on the other hand, aspires to instability. It aims at creating something that did not exist before. It seeks a break with the past with an eye on the future.

It is an irony that in today's world, feudalism can be sustained only in the administration of a modern scientific research centre. One must, however, not be unfair to the feudal lords of yesteryears whose conduct had the sanction of the times. Neo-feudalism is pernicious because it is anachronistic; it can be sustained only by a subversion of the system in the hands of the people who are entrusted with the task of upholding it.

If we define professionalism as the realisation that an institution ranks higher than an individual and that the collective goal is more important than individual ego, it must be admitted that we are unprofessional people. It is wrong in principle to give any individual a larger-than-the-institution image. This philosophy becomes all the more debilitating, because recently there has been an alarming decline in the quality of leadership in science as in other walks of life. It is relatively speaking an easy matter to evaluate a leader. His commitment can be judged by asking whether he is giving to the system or taking from it. The calibre of a leader can be gauged from the calibre of the people willing to play second fiddle to him.

Under these circumstances, if a chief executive is to be projected as the master of an institution rather than its servant, this can be done only by degrading the institution. It will be like a cinema hall whose facade remains the same, but the posters outside and the picture inside go on changing.

Q. The author suggests that the power which a senior scientist exercises over his juniors is due to

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

The young scientist in India is an endangered species. The threat comes from the predatory habits of a more evolved species that is the senior scientist. An Indian university teacher in a letter to the international science journal Nature wrote plaintively: ''Thesis supervisors take undue credit for the work of their protégés''. A young scientist needs the goodwill and support of the scientist-in-power at every step: for completion and continuation of his work, for participation in national and international meetings and research projects, for recognition and reward and for promotion. This support is available but at a price. The price often is the sharing of credit. A worthwhile research paper or a project originating from a humble scientist would often end up with the scientist-in-power as the principal author or investigator.

The power of the senior scientist over his junior stems from the fact that science is the only profession in the world which is self-assessing. Unlike in the bureaucracy or the military where the top authority vests with non-professionals, a scientist's work can be overseen and evaluated only by fellow scientists.

Fortunately for the scientists, support for science is a badge of honour for nations aspiring to modernity. That is why the government which normally would not pay the piper unless it can call the tune, happily makes an exception in the case of science. Society values continuity, stability and security, and turns to the past for guidance and support. Science, on the other hand, aspires to instability. It aims at creating something that did not exist before. It seeks a break with the past with an eye on the future.

It is an irony that in today's world, feudalism can be sustained only in the administration of a modern scientific research centre. One must, however, not be unfair to the feudal lords of yesteryears whose conduct had the sanction of the times. Neo-feudalism is pernicious because it is anachronistic; it can be sustained only by a subversion of the system in the hands of the people who are entrusted with the task of upholding it.

If we define professionalism as the realisation that an institution ranks higher than an individual and that the collective goal is more important than individual ego, it must be admitted that we are unprofessional people. It is wrong in principle to give any individual a larger-than-the-institution image. This philosophy becomes all the more debilitating, because recently there has been an alarming decline in the quality of leadership in science as in other walks of life. It is relatively speaking an easy matter to evaluate a leader. His commitment can be judged by asking whether he is giving to the system or taking from it. The calibre of a leader can be gauged from the calibre of the people willing to play second fiddle to him.

Under these circumstances, if a chief executive is to be projected as the master of an institution rather than its servant, this can be done only by degrading the institution. It will be like a cinema hall whose facade remains the same, but the posters outside and the picture inside go on changing.

Q. The author calls ''neo-feudalism'' pernicious because

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the given question.

There is a history of intimate links between the study of dreams and the US advertising industry. Sigmund Freud's nephew Edward Bernays is credited with pioneering the US public relations and advertising industries, in part through influential books such as Propaganda (1928). It was Freud's theories, which examined the nature of dreams and the unconscious, that Bernays took as inspiration for his approaches to influencing the public, with a focus on the creation of unconscious desires and associations. In a series of hugely successful advertising campaigns, Bernays demonstrated that the irrational forces that drive human behaviour could be harnessed to 'engineer consent' and manipulate people's behaviour without their realising it. It is psychoanalysis that gave advertising the idea to sell by association, linking cars and masculinity or cigarettes and freedom, just as the Coors dream-incubation project linked beer with positive, refreshing experiences.

Bernays inspired a wave of advertising industry leaders in the ensuing decades to hire 'motivational analysts' and 'depth manipulators', who sought to uncover and redirect the unconscious desires of consumers. The use of subliminal stimuli, first explored in perception and attention laboratories, seemed well suited to their purposes. Research suggested subliminal stimuli might be able to deliver messaging below a person's perceptual threshold, allowing for the undetected insertion of new motivations and meaningful associations in vulnerable viewers.

In 1957, a press conference from the market researcher James Vicary – claiming that flashing the phrases 'Eat popcorn' and 'Drink Coca-Cola' during a film significantly increased the sale of these products – hit a raw nerve. Claims about the potential of subliminal messaging smacked of manipulation by a Communist state broadcast. A demonstration of subliminal advertising was demanded and held for the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and members of Congress, where 'Eat popcorn' was flashed at the attendees during a TV programme. But the response was mild: one senator reportedly quipped 'I think I want a hot dog,' and it seems that nobody was overcome with a desire for popcorn.

It's not surprising that the audience was unmoved; the evidence for large behavioural effects caused by subliminal advertising was, and remains, quite weak. By his own admission (five years after the fact), Vicary had faked his study. Nevertheless, the FCC has stated that: 'Regardless of whether it is effective, the broadcast of subliminal material is inconsistent with a station's obligation to serve the public interest because it is designed to be deceptive.' In the view of the regulatory body, a message that seeks to circumvent the awareness of a listener to influence them without their being able to assess it is, by nature, deceptive. More generally, the Federal Trade Commission, which has the power to regulate all advertising, has concluded that: 'It would be deceptive for marketers to embed ads with so-called subliminal messages that could affect consumer behaviour,' making it a prohibited form of advertising. But no extension of these prohibitions to dream hacking has been made, and the advertising industry must be aware of this lack.

Q. All of the following statements can be inferred about 'engineer[ing] consent' as mentioned in the first paragraph EXCEPT:

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the given question.

There is a history of intimate links between the study of dreams and the US advertising industry. Sigmund Freud's nephew Edward Bernays is credited with pioneering the US public relations and advertising industries, in part through influential books such as Propaganda (1928). It was Freud's theories, which examined the nature of dreams and the unconscious, that Bernays took as inspiration for his approaches to influencing the public, with a focus on the creation of unconscious desires and associations. In a series of hugely successful advertising campaigns, Bernays demonstrated that the irrational forces that drive human behaviour could be harnessed to 'engineer consent' and manipulate people's behaviour without their realising it. It is psychoanalysis that gave advertising the idea to sell by association, linking cars and masculinity or cigarettes and freedom, just as the Coors dream-incubation project linked beer with positive, refreshing experiences.

Bernays inspired a wave of advertising industry leaders in the ensuing decades to hire 'motivational analysts' and 'depth manipulators', who sought to uncover and redirect the unconscious desires of consumers. The use of subliminal stimuli, first explored in perception and attention laboratories, seemed well suited to their purposes. Research suggested subliminal stimuli might be able to deliver messaging below a person's perceptual threshold, allowing for the undetected insertion of new motivations and meaningful associations in vulnerable viewers.

In 1957, a press conference from the market researcher James Vicary – claiming that flashing the phrases 'Eat popcorn' and 'Drink Coca-Cola' during a film significantly increased the sale of these products – hit a raw nerve. Claims about the potential of subliminal messaging smacked of manipulation by a Communist state broadcast. A demonstration of subliminal advertising was demanded and held for the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and members of Congress, where 'Eat popcorn' was flashed at the attendees during a TV programme. But the response was mild: one senator reportedly quipped 'I think I want a hot dog,' and it seems that nobody was overcome with a desire for popcorn.

It's not surprising that the audience was unmoved; the evidence for large behavioural effects caused by subliminal advertising was, and remains, quite weak. By his own admission (five years after the fact), Vicary had faked his study. Nevertheless, the FCC has stated that: 'Regardless of whether it is effective, the broadcast of subliminal material is inconsistent with a station's obligation to serve the public interest because it is designed to be deceptive.' In the view of the regulatory body, a message that seeks to circumvent the awareness of a listener to influence them without their being able to assess it is, by nature, deceptive. More generally, the Federal Trade Commission, which has the power to regulate all advertising, has concluded that: 'It would be deceptive for marketers to embed ads with so-called subliminal messages that could affect consumer behaviour,' making it a prohibited form of advertising. But no extension of these prohibitions to dream hacking has been made, and the advertising industry must be aware of this lack.

Q. Which of the following does the author imply when he mentions the importance of delivering a message 'below a person's perceptual threshold' in the second paragraph?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the given question.

There is a history of intimate links between the study of dreams and the US advertising industry. Sigmund Freud's nephew Edward Bernays is credited with pioneering the US public relations and advertising industries, in part through influential books such as Propaganda (1928). It was Freud's theories, which examined the nature of dreams and the unconscious, that Bernays took as inspiration for his approaches to influencing the public, with a focus on the creation of unconscious desires and associations. In a series of hugely successful advertising campaigns, Bernays demonstrated that the irrational forces that drive human behaviour could be harnessed to 'engineer consent' and manipulate people's behaviour without their realising it. It is psychoanalysis that gave advertising the idea to sell by association, linking cars and masculinity or cigarettes and freedom, just as the Coors dream-incubation project linked beer with positive, refreshing experiences.

Bernays inspired a wave of advertising industry leaders in the ensuing decades to hire 'motivational analysts' and 'depth manipulators', who sought to uncover and redirect the unconscious desires of consumers. The use of subliminal stimuli, first explored in perception and attention laboratories, seemed well suited to their purposes. Research suggested subliminal stimuli might be able to deliver messaging below a person's perceptual threshold, allowing for the undetected insertion of new motivations and meaningful associations in vulnerable viewers.

In 1957, a press conference from the market researcher James Vicary – claiming that flashing the phrases 'Eat popcorn' and 'Drink Coca-Cola' during a film significantly increased the sale of these products – hit a raw nerve. Claims about the potential of subliminal messaging smacked of manipulation by a Communist state broadcast. A demonstration of subliminal advertising was demanded and held for the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and members of Congress, where 'Eat popcorn' was flashed at the attendees during a TV programme. But the response was mild: one senator reportedly quipped 'I think I want a hot dog,' and it seems that nobody was overcome with a desire for popcorn.

It's not surprising that the audience was unmoved; the evidence for large behavioural effects caused by subliminal advertising was, and remains, quite weak. By his own admission (five years after the fact), Vicary had faked his study. Nevertheless, the FCC has stated that: 'Regardless of whether it is effective, the broadcast of subliminal material is inconsistent with a station's obligation to serve the public interest because it is designed to be deceptive.' In the view of the regulatory body, a message that seeks to circumvent the awareness of a listener to influence them without their being able to assess it is, by nature, deceptive. More generally, the Federal Trade Commission, which has the power to regulate all advertising, has concluded that: 'It would be deceptive for marketers to embed ads with so-called subliminal messages that could affect consumer behaviour,' making it a prohibited form of advertising. But no extension of these prohibitions to dream hacking has been made, and the advertising industry must be aware of this lack.

Q. According to the passage, why did James Vicary's claim about the effectiveness of subliminal advertising 'hit a raw nerve'?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the given question.

There is a history of intimate links between the study of dreams and the US advertising industry. Sigmund Freud's nephew Edward Bernays is credited with pioneering the US public relations and advertising industries, in part through influential books such as Propaganda (1928). It was Freud's theories, which examined the nature of dreams and the unconscious, that Bernays took as inspiration for his approaches to influencing the public, with a focus on the creation of unconscious desires and associations. In a series of hugely successful advertising campaigns, Bernays demonstrated that the irrational forces that drive human behaviour could be harnessed to 'engineer consent' and manipulate people's behaviour without their realising it. It is psychoanalysis that gave advertising the idea to sell by association, linking cars and masculinity or cigarettes and freedom, just as the Coors dream-incubation project linked beer with positive, refreshing experiences.

Bernays inspired a wave of advertising industry leaders in the ensuing decades to hire 'motivational analysts' and 'depth manipulators', who sought to uncover and redirect the unconscious desires of consumers. The use of subliminal stimuli, first explored in perception and attention laboratories, seemed well suited to their purposes. Research suggested subliminal stimuli might be able to deliver messaging below a person's perceptual threshold, allowing for the undetected insertion of new motivations and meaningful associations in vulnerable viewers.

In 1957, a press conference from the market researcher James Vicary – claiming that flashing the phrases 'Eat popcorn' and 'Drink Coca-Cola' during a film significantly increased the sale of these products – hit a raw nerve. Claims about the potential of subliminal messaging smacked of manipulation by a Communist state broadcast. A demonstration of subliminal advertising was demanded and held for the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and members of Congress, where 'Eat popcorn' was flashed at the attendees during a TV programme. But the response was mild: one senator reportedly quipped 'I think I want a hot dog,' and it seems that nobody was overcome with a desire for popcorn.

It's not surprising that the audience was unmoved; the evidence for large behavioural effects caused by subliminal advertising was, and remains, quite weak. By his own admission (five years after the fact), Vicary had faked his study. Nevertheless, the FCC has stated that: 'Regardless of whether it is effective, the broadcast of subliminal material is inconsistent with a station's obligation to serve the public interest because it is designed to be deceptive.' In the view of the regulatory body, a message that seeks to circumvent the awareness of a listener to influence them without their being able to assess it is, by nature, deceptive. More generally, the Federal Trade Commission, which has the power to regulate all advertising, has concluded that: 'It would be deceptive for marketers to embed ads with so-called subliminal messages that could affect consumer behaviour,' making it a prohibited form of advertising. But no extension of these prohibitions to dream hacking has been made, and the advertising industry must be aware of this lack.

Q. "But no extension of these prohibitions to dream hacking has been made, and the advertising industry must be aware of this lack."

All of the following is implied in this last line of the passage EXCEPT:

Directions: The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, 4) given below, when properly sequenced would yield a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper sequence of the order of the sentences and key in the sequence of the four numbers as your answer.

1. Literary works such as Byron's Darkness, Percy Shelley's Mont Blanc, and Mary Shelley's Frankenstein reveal anxieties about human vulnerability to environmental change even as they address our power to manipulate our environments.

2. Historical texts reflect the changing climatic conditions that produced them.

3. This was caused largely by the massive eruption of the Indonesian volcano Mount Tambora the previous year, which lowered global temperatures and led to harvest failures and famine.

4. When Byron and the Shelleys stayed on the shores of Lake Geneva in 1816, the literature that they wrote responded to the wild weather of the year without a summer.

Directions: There is a sentence that is missing in the paragraph below. Look at the paragraph and decide in which blank (option 1, 2, 3, or 4) the following sentence would best fit.

Sentence: The aesthetic realm sits, rather, askance to politics; it allows us to attend to politics but relieves us from the weight of taking on a political position.

Paragraph: Art, perhaps uniquely among the forms of political discourse available to us, allows for audiences to contemplate issues at the heart of political clashes, while temporarily suspending the judgment of right and wrong. ___(1)___. The space of aesthetics is therefore neither fully political nor anti-political. ___(2)___. None of this is to suggest, of course, that this aesthetic, inconclusive mode is better than either objectivity or activism. ___(3)___. Instead, the suggestion is that the democratic public sphere requires a plurality of these different modes of discourse, among which the arts play their distinctive role. ___(4)___.

Directions: The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, and 4) below, when properly sequenced, would yield a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper sequencing of the order of the sentences and key in the sequence of the four numbers as your answer.

1. The human experience of space is intimately connected to the temporal structure of those activities by means of which we experience space.

2. Nonetheless, they generally agree that alterations in humanity's experiences of space and time are working to undermine the importance of local and even national boundaries in many arenas of human endeavor.

3. Changes in the temporality of human activity inevitably generate altered experiences of space or territory.

4. Theorists of globalization disagree about the precise sources of recent shifts in the spatial and temporal contours of human life.

Directions: There is a sentence that is missing in the paragraph below. Look at the paragraph and decide in which blank (option 1, 2, 3, or 4) the following sentence would best fit.

Sentence: Many companies still use outdated, energy-inefficient designs or do not have the resources to invest in cooling or power-optimisation solutions.

Paragraph: Data centres differ based on their technological sophistication: there is a tiering system that ranks centres according to their resources, scale of operation, and level of redundancies. ___(1)___. Only about one-third of the world's data centres resemble the oft-circulated images of Google's idyllic facilities, glittering with colourful pipes and smiling technicians who get around their workplaces on scooters. ___(2)___. The remaining two-thirds of data centres are far less impressive. Some are found in mouldy basements, others in the shells of decaying office buildings or abandoned military installations. ___(3)___. As such, the workers in these facilities must rely more readily on their experiences and finely tuned instincts to keep their patches of the cloud 'up', however imperfectly. ___(4)___. They do not see themselves as automatons, as mere cogs in a perfectly optimised machine, but rather as hunters, firefighters or even priests, who must make, find or invent ways to meet the impossible demand of an unremitting cloud.

Directions: Four alternative summaries are given below the text. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the text.

Some decisions will be fairly obvious - no-brainers. Your bank account is low, but you have a two-week vacation coming up and you want to get away to some place warm to relax with your family. Will you accept your in-laws' offer of free use of their Florida beachfront condo? Sure. You like your employer and feel ready to move forward in your career. Will you step in for your boss for three weeks while she attends a professional development course? Of course.

Directions: Four alternative summaries are given below the text. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the text.

It is important for shipping companies to be clear about the objectives for maintenance and materials management as to whether the primary focus is on service level improvement or cost minimization. Often when certain systems are set in place, the cost minimisation objective and associated procedure become more important than the flexibility required for service level improvement. The problem really arises since cost minimisation tends to focus on out of pocket costs which are visible, while the opportunity costs, often greater in value, are lost sight of.

Directions: The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, 4) given below, when properly sequenced would yield a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper sequence of the order of the sentences and key in the sequence of the four numbers as your answer.

1. Studies with recent evidence looking at digital interventions for behaviour change show promise for those living with chronic disease.

2. Given its global adoption and growing popularity among older adults, mobile technology may be an effective strategy to improve medication adherence.

3. Text-message based interventions have been considered feasible and favourable given their automated administration, long-standing use, and ease of use.

4. Medication non-adherence is linked to adverse clinical outcomes among patients with coronary heart disease.

Directions: Four alternative summaries are given below the text. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the text.

Free will plays a crucial role to mould our destiny. Everyone has the option to take decisions using his or her own free will. If we take correct decisions and act accordingly, nothing can prevent us from achieving what we want to achieve. The outcome of any act depends on many factors over which we have no control. That is why even the best laid out plans of the most intelligent people end up in utter chaos. To shape our destiny, free will becomes a prerequisite. Destiny is derived from our past, free from the present. What you are now is the result of what you did in the past. What you shall be in the future will be the result of what you think and are doing now. There are many ways to reach a destination; it's upon our free will to choose the road so as to achieve success or failure.

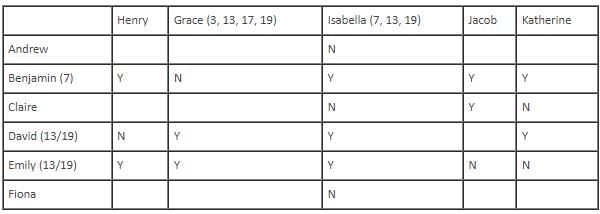

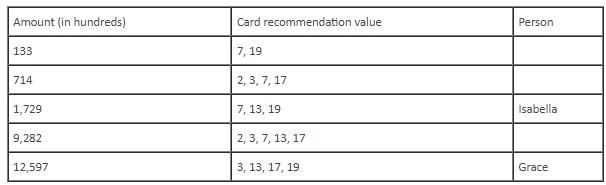

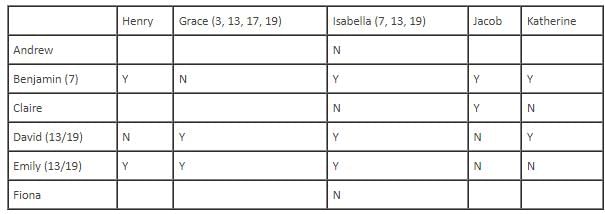

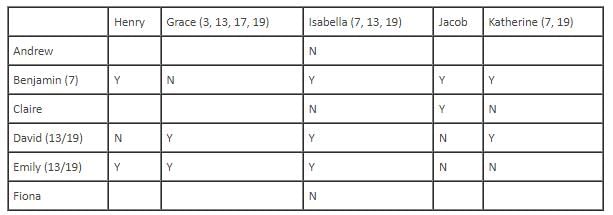

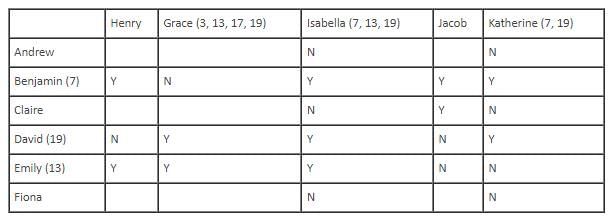

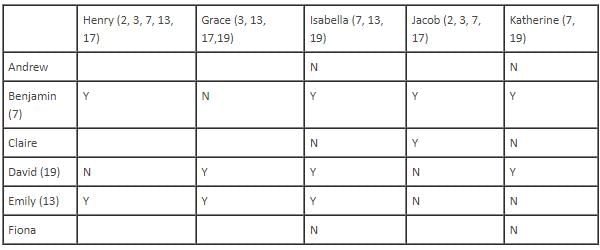

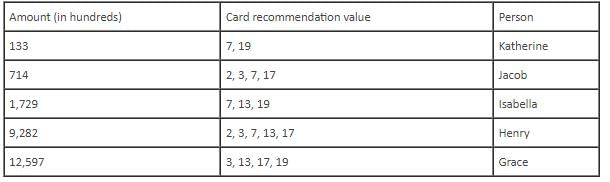

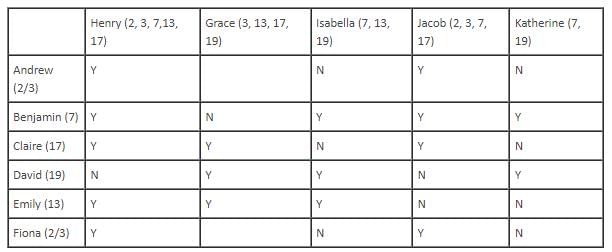

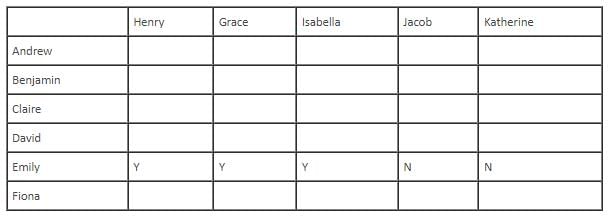

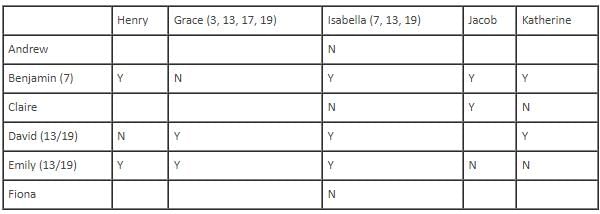

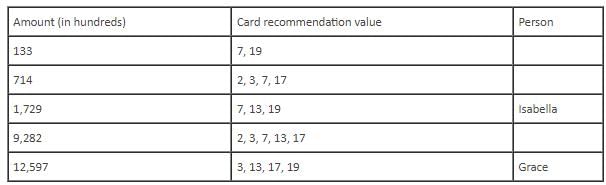

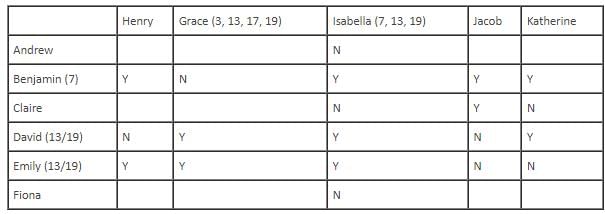

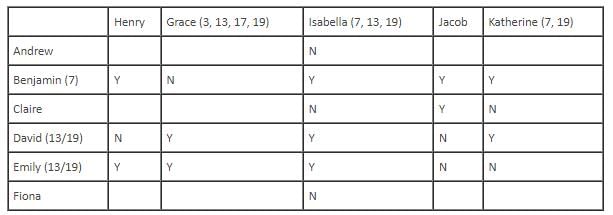

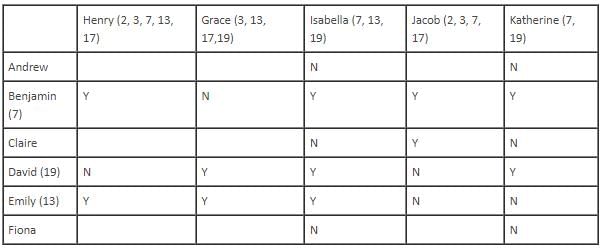

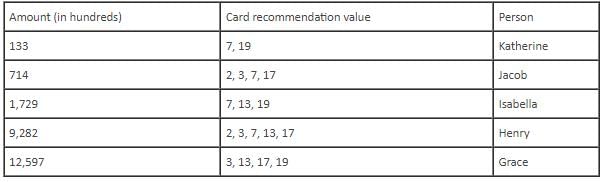

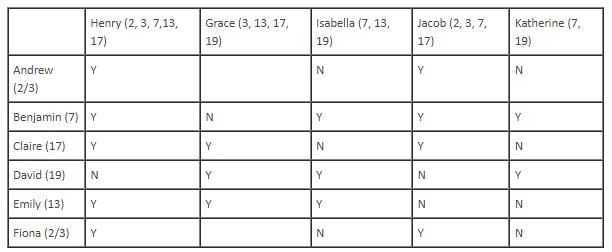

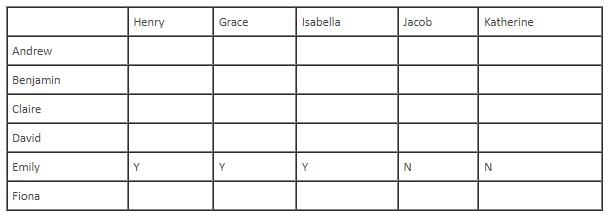

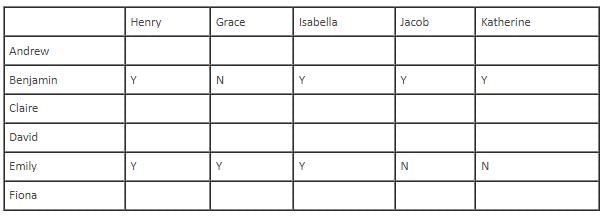

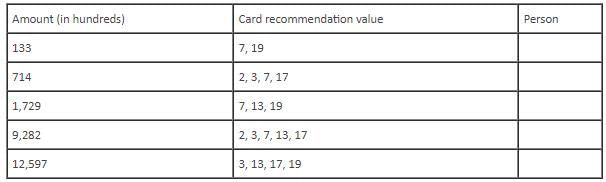

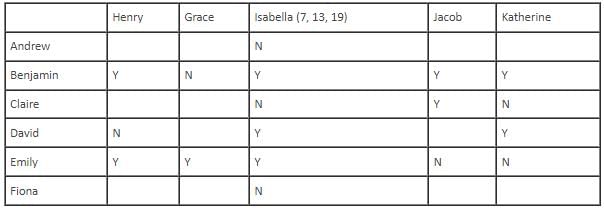

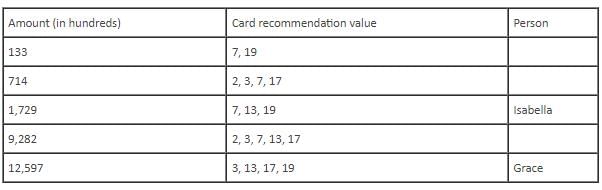

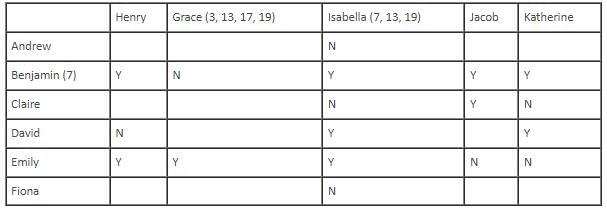

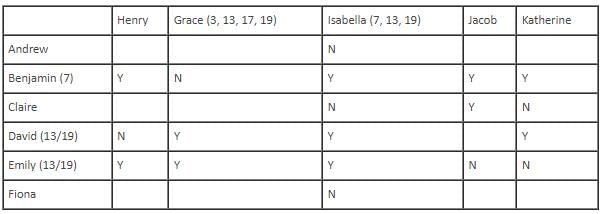

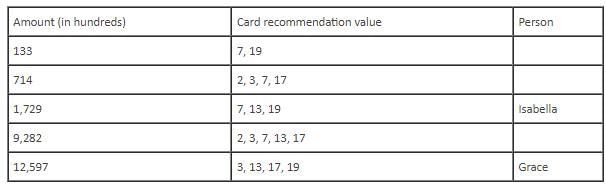

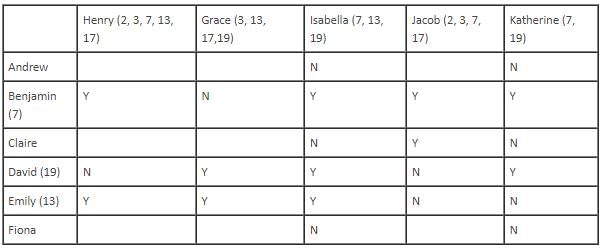

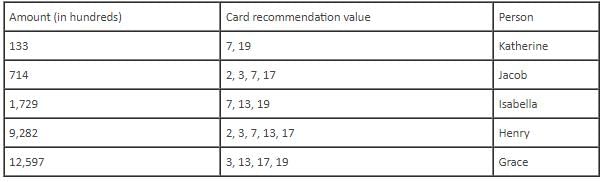

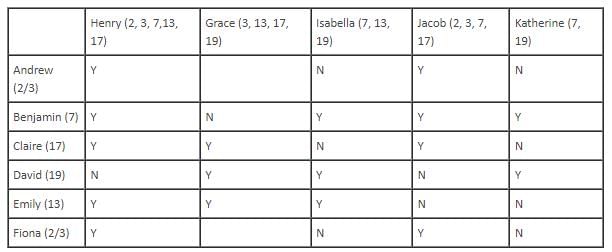

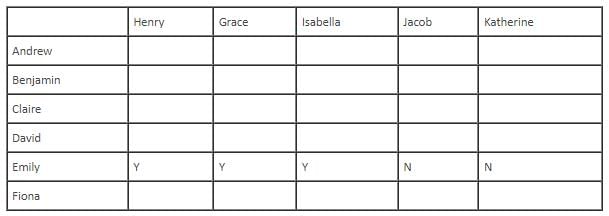

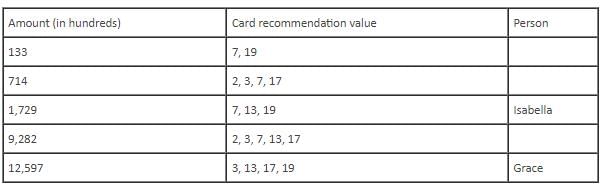

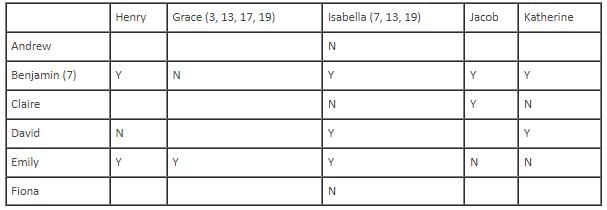

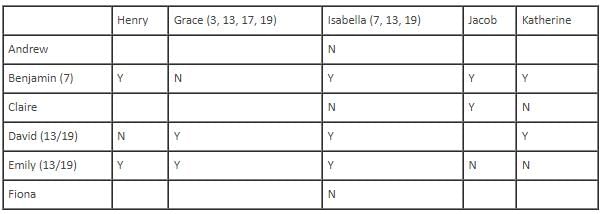

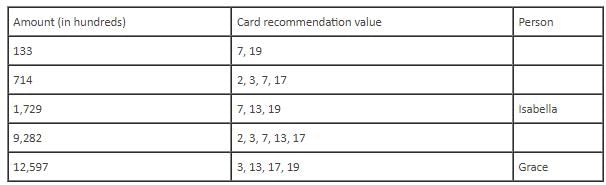

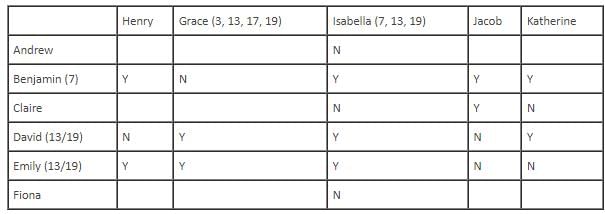

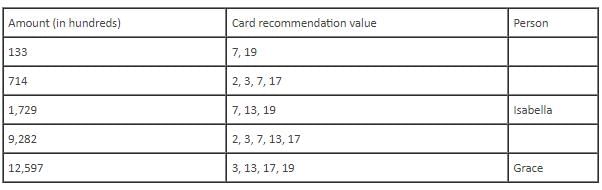

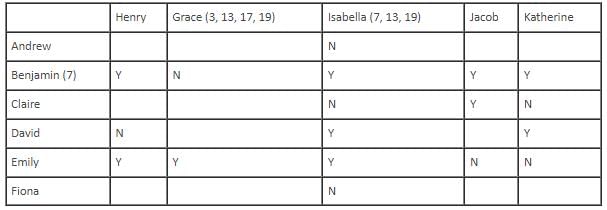

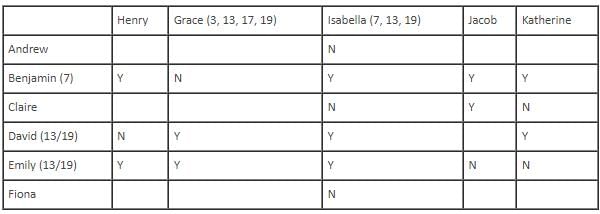

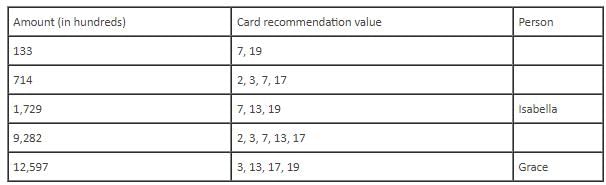

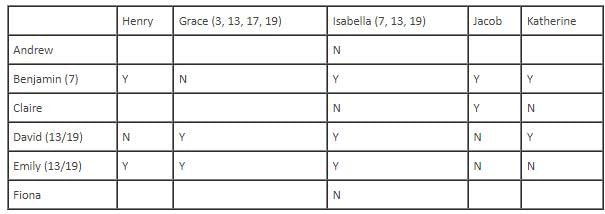

Directions: Answer the question on the basis of the information given below.

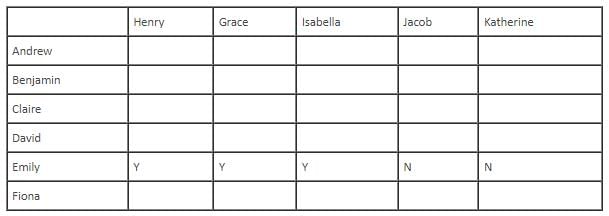

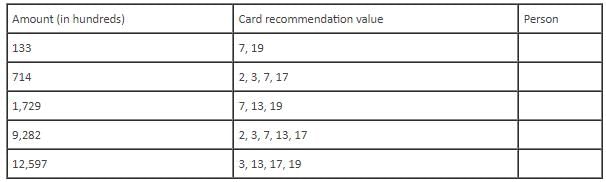

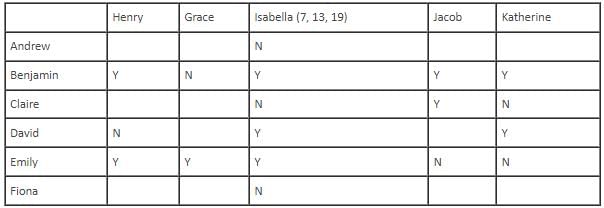

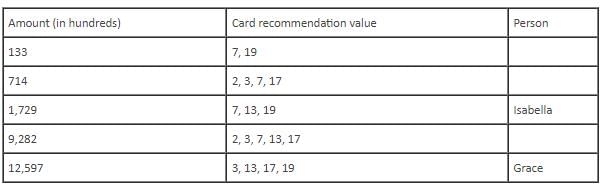

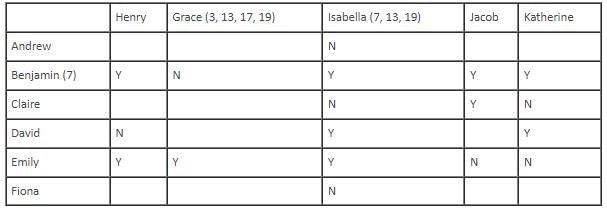

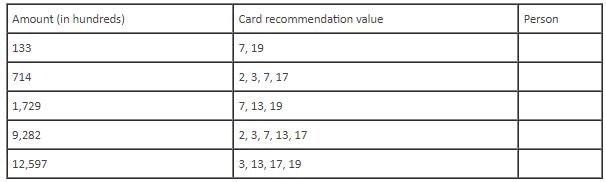

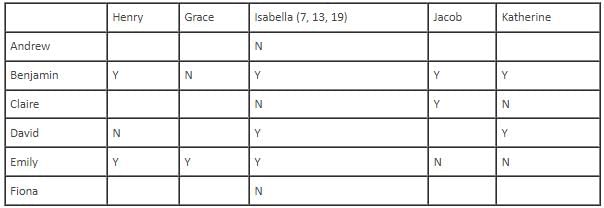

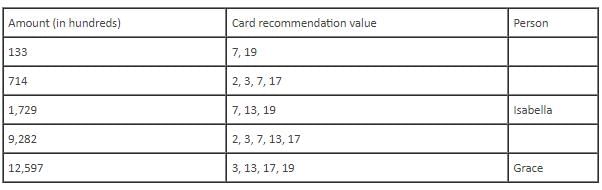

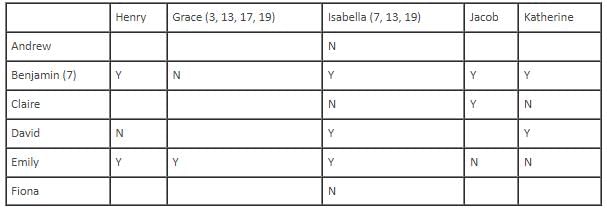

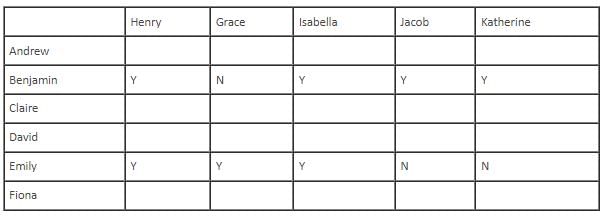

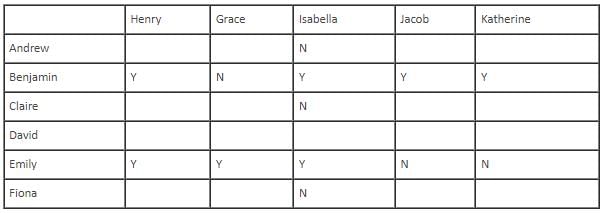

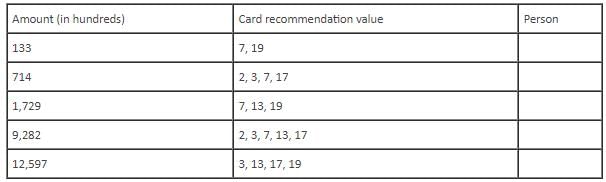

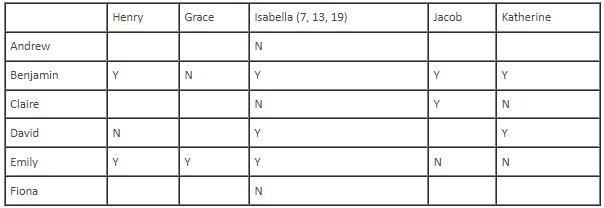

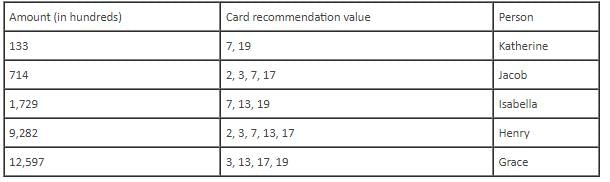

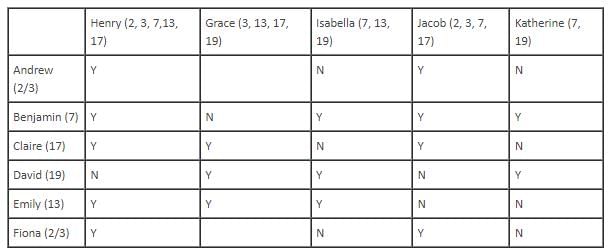

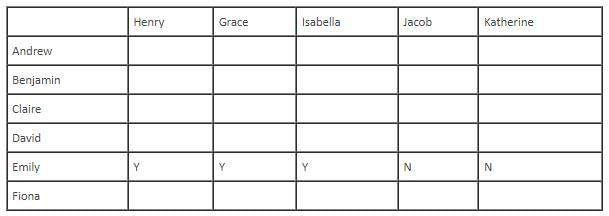

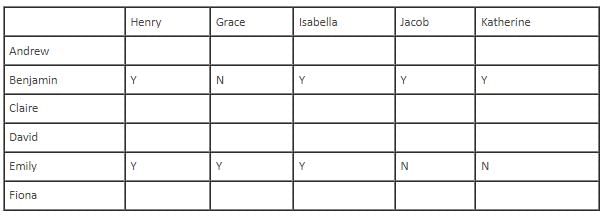

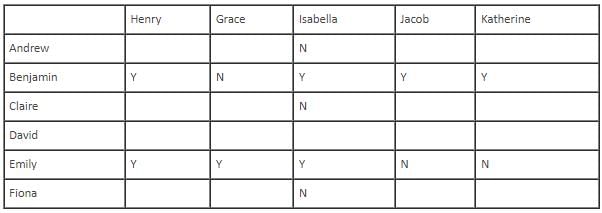

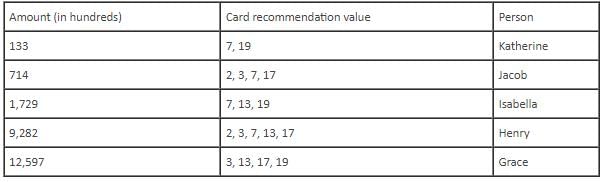

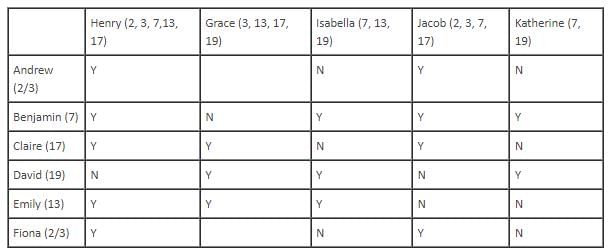

In a prestigious scholarship selection process, a committee comprised of professors and professionals came together to evaluate and award scholarships to exceptional students. The committee members were Andrew, Benjamin, Claire, David, Emily, and Fiona. Every committee member individually interviewed each of the students individually and awarded a recommendatory card only if he found him to be truly deserving. The card recommendation value was denoted as 2, 3, 7, 13, 17 or 19. Each interviewer awarded card of a single recommendation value only. Upon the completion of all interviews for a candidate, the scholarship amount awarded was determined by multiplying the card recommendation value they received by a factor of 100. For example, if a candidate card recommendation values are 7, 13, and 17, their total scholarship amount would be Rs. 100 × (7 × 13 × 17) equaling Rs. 1,54,700. Among the brilliant recipients of scholarships, let's consider the following five students: Grace, Henry, Isabella, Jacob, and Katherine. The scholarships they were granted, in ascending order, were Rs. 13,300, Rs. 71,400, Rs. 1,72,900, Rs. 9,28,200, and Rs. 12,59,700, respectively. Now, let's explore some additional facts about the selection process:

(i) Emily awarded cards to all the candidates except Katherine and Jacob.

(ii) Benjamin granted cards to all except Grace.

(iii) Isabella received the second lowest number of cards.

(iv) Among Andrew, Claire and Fiona, no one awarded any card to Isabella.

(v) David chose to award a card to Katherine but not to Henry.

(vi) Claire decided to bestow a card upon Jacob but not Katherine.

Q. The amount of scholarship received by Henry was

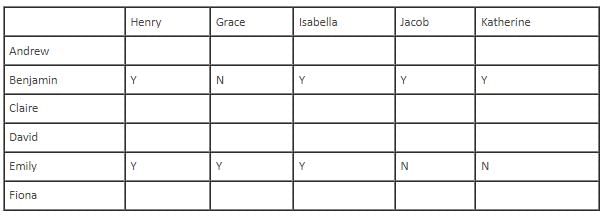

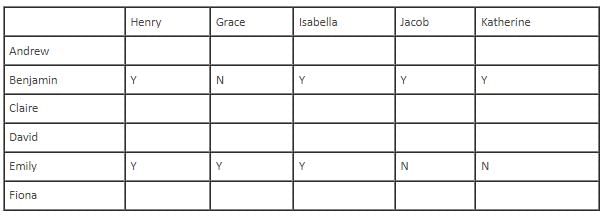

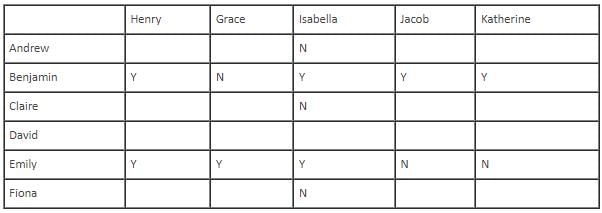

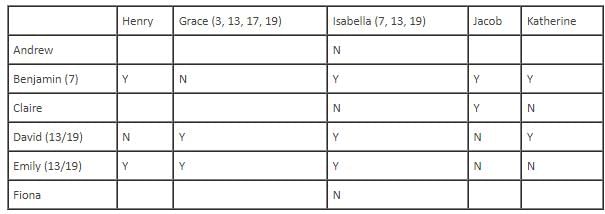

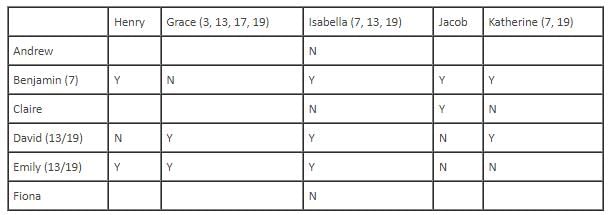

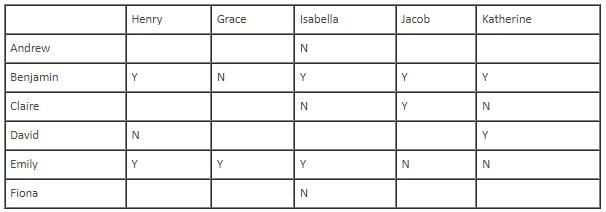

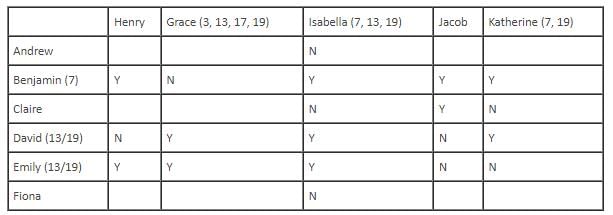

Directions: Answer the question on the basis of the information given below.

In a prestigious scholarship selection process, a committee comprised of professors and professionals came together to evaluate and award scholarships to exceptional students. The committee members were Andrew, Benjamin, Claire, David, Emily, and Fiona. Every committee member individually interviewed each of the students individually and awarded a recommendatory card only if he found him to be truly deserving. The card recommendation value was denoted as 2, 3, 7, 13, 17 or 19. Each interviewer awarded card of a single recommendation value only. Upon the completion of all interviews for a candidate, the scholarship amount awarded was determined by multiplying the card recommendation value they received by a factor of 100. For example, if a candidate card recommendation values are 7, 13, and 17, their total scholarship amount would be Rs. 100 × (7 × 13 × 17) equaling Rs. 1,54,700. Among the brilliant recipients of scholarships, let's consider the following five students: Grace, Henry, Isabella, Jacob, and Katherine. The scholarships they were granted, in ascending order, were Rs. 13,300, Rs. 71,400, Rs. 1,72,900, Rs. 9,28,200, and Rs. 12,59,700, respectively. Now, let's explore some additional facts about the selection process:

(i) Emily awarded cards to all the candidates except Katherine and Jacob.

(ii) Benjamin granted cards to all except Grace.

(iii) Isabella received the second lowest number of cards.

(iv) Among Andrew, Claire and Fiona, no one awarded any card to Isabella.

(v) David chose to award a card to Katherine but not to Henry.

(vi) Claire decided to bestow a card upon Jacob but not Katherine.

Q. Fiona awarded cards to how many students?

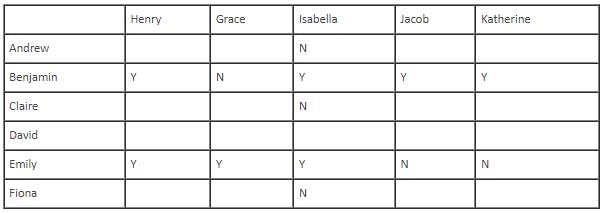

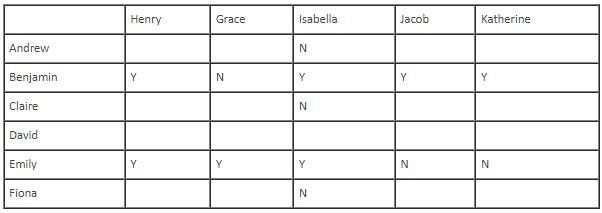

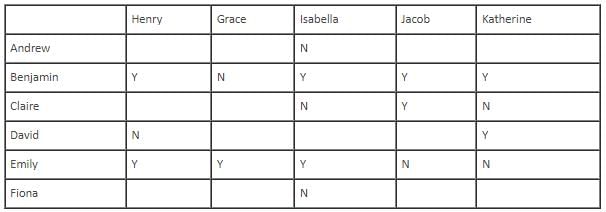

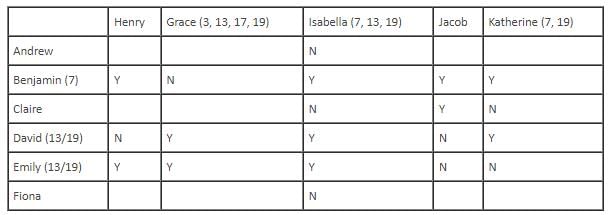

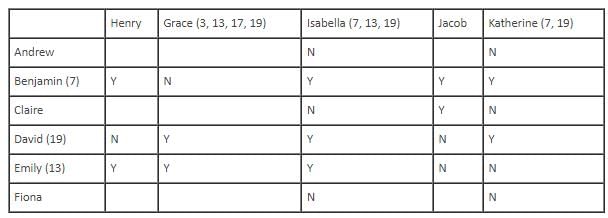

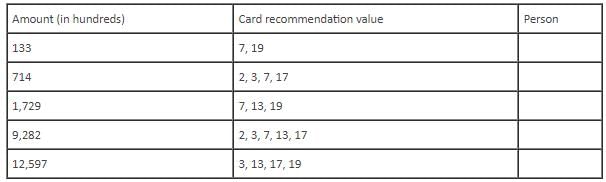

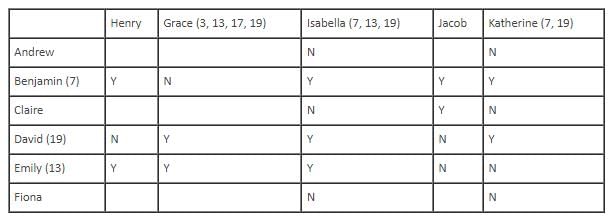

Directions: Answer the question on the basis of the information given below.

In a prestigious scholarship selection process, a committee comprised of professors and professionals came together to evaluate and award scholarships to exceptional students. The committee members were Andrew, Benjamin, Claire, David, Emily, and Fiona. Every committee member individually interviewed each of the students individually and awarded a recommendatory card only if he found him to be truly deserving. The card recommendation value was denoted as 2, 3, 7, 13, 17 or 19. Each interviewer awarded card of a single recommendation value only. Upon the completion of all interviews for a candidate, the scholarship amount awarded was determined by multiplying the card recommendation value they received by a factor of 100. For example, if a candidate card recommendation values are 7, 13, and 17, their total scholarship amount would be Rs. 100 × (7 × 13 × 17) equaling Rs. 1,54,700. Among the brilliant recipients of scholarships, let's consider the following five students: Grace, Henry, Isabella, Jacob, and Katherine. The scholarships they were granted, in ascending order, were Rs. 13,300, Rs. 71,400, Rs. 1,72,900, Rs. 9,28,200, and Rs. 12,59,700, respectively. Now, let's explore some additional facts about the selection process:

(i) Emily awarded cards to all the candidates except Katherine and Jacob.

(ii) Benjamin granted cards to all except Grace.

(iii) Isabella received the second lowest number of cards.

(iv) Among Andrew, Claire and Fiona, no one awarded any card to Isabella.

(v) David chose to award a card to Katherine but not to Henry.

(vi) Claire decided to bestow a card upon Jacob but not Katherine.

Q. Which of the following members awarded a card to Isabella?

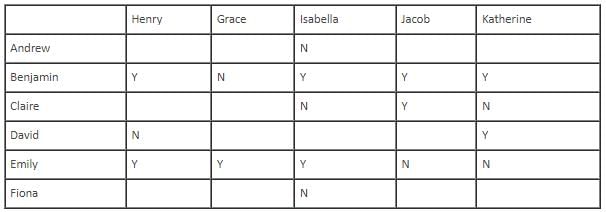

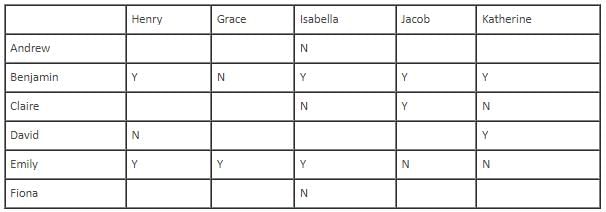

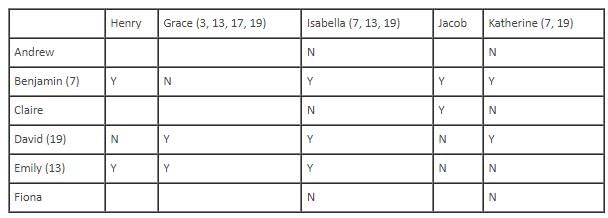

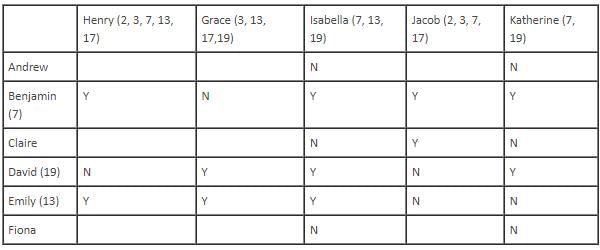

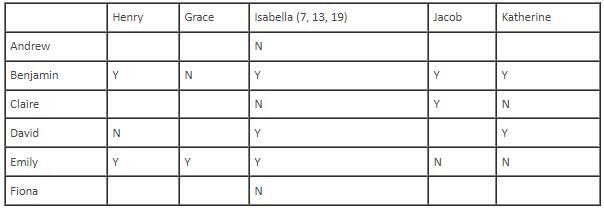

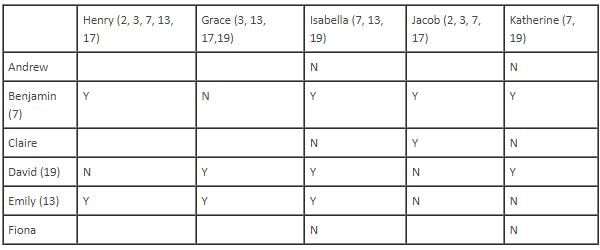

Directions: Answer the question on the basis of the information given below.

In a prestigious scholarship selection process, a committee comprised of professors and professionals came together to evaluate and award scholarships to exceptional students. The committee members were Andrew, Benjamin, Claire, David, Emily, and Fiona. Every committee member individually interviewed each of the students individually and awarded a recommendatory card only if he found him to be truly deserving. The card recommendation value was denoted as 2, 3, 7, 13, 17 or 19. Each interviewer awarded card of a single recommendation value only. Upon the completion of all interviews for a candidate, the scholarship amount awarded was determined by multiplying the card recommendation value they received by a factor of 100. For example, if a candidate card recommendation values are 7, 13, and 17, their total scholarship amount would be Rs. 100 × (7 × 13 × 17) equaling Rs. 1,54,700. Among the brilliant recipients of scholarships, let's consider the following five students: Grace, Henry, Isabella, Jacob, and Katherine. The scholarships they were granted, in ascending order, were Rs. 13,300, Rs. 71,400, Rs. 1,72,900, Rs. 9,28,200, and Rs. 12,59,700, respectively. Now, let's explore some additional facts about the selection process:

(i) Emily awarded cards to all the candidates except Katherine and Jacob.

(ii) Benjamin granted cards to all except Grace.

(iii) Isabella received the second lowest number of cards.

(iv) Among Andrew, Claire and Fiona, no one awarded any card to Isabella.

(v) David chose to award a card to Katherine but not to Henry.

(vi) Claire decided to bestow a card upon Jacob but not Katherine.

Q. Emily did not award cards to which of the following groups?

Directions: Answer the question on the basis of the information given below.

In a prestigious scholarship selection process, a committee comprised of professors and professionals came together to evaluate and award scholarships to exceptional students. The committee members were Andrew, Benjamin, Claire, David, Emily, and Fiona. Every committee member individually interviewed each of the students individually and awarded a recommendatory card only if he found him to be truly deserving. The card recommendation value was denoted as 2, 3, 7, 13, 17 or 19. Each interviewer awarded card of a single recommendation value only. Upon the completion of all interviews for a candidate, the scholarship amount awarded was determined by multiplying the card recommendation value they received by a factor of 100. For example, if a candidate card recommendation values are 7, 13, and 17, their total scholarship amount would be Rs. 100 × (7 × 13 × 17) equaling Rs. 1,54,700. Among the brilliant recipients of scholarships, let's consider the following five students: Grace, Henry, Isabella, Jacob, and Katherine. The scholarships they were granted, in ascending order, were Rs. 13,300, Rs. 71,400, Rs. 1,72,900, Rs. 9,28,200, and Rs. 12,59,700, respectively. Now, let's explore some additional facts about the selection process:

(i) Emily awarded cards to all the candidates except Katherine and Jacob.

(ii) Benjamin granted cards to all except Grace.

(iii) Isabella received the second lowest number of cards.

(iv) Among Andrew, Claire and Fiona, no one awarded any card to Isabella.

(v) David chose to award a card to Katherine but not to Henry.

(vi) Claire decided to bestow a card upon Jacob but not Katherine.

Q. Which of the following groups was awarded with a card of recommendation value 19?

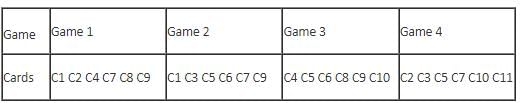

Directions: Read the following and answer the question.

Mr. Ernest who likes to play cards has eleven cards available – C1 through C11 with him. Among these eleven cards, there are five different colors of cards – Red, Blue, Yellow, White and Black – such that there are exactly three Red cards, two Blue cards, two Yellow cards, two White cards and two Black cards. The Mr. Ernest picks the six cards such that any game contains exactly two Red, one Blue, one Yellow, one White and one Black. The Mr. Ernest picked the following cards combinations for different games:

Q. Which of the following pairs of cards are definitely of the same color?