OneTime: Digital SAT Mock Test - 3 - SAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - OneTime: Digital SAT Mock Test - 3

Question based on the following passage.

The following passage is adapted from Oscar Wilde, The Canterville Ghost, published in 1887.

When Mr. Hiram B. Otis, the American

Minister, bought Canterville Chase, everyone

told him that the place was haunted. Indeed,

Lord Canterville himself, a man of punctilious

(5) honor, felt it his duty to mention the fact to Mr.

Otis when they came to discuss terms.

“We have not cared to live in the place

ourselves,” said Lord Canterville, “since the

Dowager Duchess of Bolton was frightened into

(10) a fit by two skeleton hands on her shoulders as

she was dressing for dinner. The ghost has been

seen by several members of my family, as well as

by the Rev. Augustus Dampier, a Fellow of King’s

College, Cambridge.”

(15) “My Lord,” answered the Minister, “I will

take the furniture and the ghost at a valuation. I

come from a modern country, and I reckon that if

there were such a thing as a ghost in Europe, we’d

have it at home in a very short time in one of our

(20) public museums.”

“I fear that the ghost exists,” said Lord

Canterville, smiling, “though it may have resisted

the overtures of your enterprising impresarios.

It has been well known for three centuries, since

(25) 1584 in fact, and always makes its appearance

before the death of any member of our family.”

“Well, so does the family doctor for that

matter, Lord Canterville. But there is no such

thing, sir, as a ghost, and I guess the laws of

(30) Nature are not going to be suspended for the

British aristocracy.”

After the purchase was concluded, the

Minister and his family went down to Canterville

Chase. Mrs. Otis, who, as Miss Lucretia R. Tappan

(35) had been a celebrated New York belle, was now a

very handsome, middle-aged woman. Her eldest

son, christened Washington by his parents in a

moment of patriotism, was a fair-haired, rather

good-looking young man.

(40) Standing on the steps to receive them was old

Mrs. Umney, the housekeeper, whom Mrs. Otis, at

Lady Canterville's earnest request, had consented

to keep on in her former position. Following her

into the library, they found tea laid out for them,

(45) sat down and began to look round.

Suddenly Mrs. Otis caught sight of a dull red

stain on the floor just by the fireplace and said

to Mrs. Umney, “I am afraid something has been

spilt there.”

(50) “Yes, madam,” replied the old housekeeper in

a low voice, “blood has been spilt on that spot.”

“How horrid,” cried Mrs. Otis; “I don't at all

care for bloodstains in a sitting-room. It must be

removed at once.”

(55) The old woman answered in the same low,

mysterious voice, “It is the blood of Lady Eleanore

de Canterville, who was murdered on that spot by

her husband, Sir Simon de Canterville, in 1575.

His guilty spirit still haunts the Chase. The blood-

(60) stain has been much admired by tourists and

others, and cannot be removed.”

“That is all nonsense,” cried Washington;

“Pinkerton's Champion Stain Remover will

clean it up in no time,” and before the terrified

(65) housekeeper could interfere he was rapidly

scouring the floor. In a few moments no trace of

the blood-stain could be seen.

“I knew Pinkerton would do it,” he exclaimed

triumphantly, as he looked round at his admiring

(70) family. A terrible flash of lightning lit up the

somber room, a fearful peal of thunder made them

all start to their feet, and Mrs. Umney fainted.

“What a monstrous climate!” said the

American Minister calmly. “I guess the old

(75) country is so overpopulated that they have not

enough decent weather for everybody. I have

always been of opinion that emigration is the

only thing for England.”

“My dear Hiram,” cried Mrs. Otis, “what can

(80) we do with a woman who faints?”

“Charge it to her like breakages,” answered

the Minister; “she won't faint after that;” and in

a few moments Mrs. Umney certainly came to.

There was no doubt, however, that she was upset,

(85) and she sternly warned Mr. Otis to beware of

some trouble coming to the house.

“Many and many a night,” she said, “I have

not closed my eyes in sleep for the awful things

that are done here.” Mr. Otis, however, and his

(90) wife warmly assured the honest soul that they

were not afraid of ghosts, and, after invoking

the blessings of Providence on her new master

and mistress, and making arrangements for an

increase of salary, the old housekeeper tottered

(95) off to her own room.

Q. Which choice best describes what happens in the passage?

The following passage is adapted from Oscar Wilde, The Canterville Ghost, published in 1887.

When Mr. Hiram B. Otis, the American

Minister, bought Canterville Chase, everyone

told him that the place was haunted. Indeed,

Lord Canterville himself, a man of punctilious

(5) honor, felt it his duty to mention the fact to Mr.

Otis when they came to discuss terms.

“We have not cared to live in the place

ourselves,” said Lord Canterville, “since the

Dowager Duchess of Bolton was frightened into

(10) a fit by two skeleton hands on her shoulders as

she was dressing for dinner. The ghost has been

seen by several members of my family, as well as

by the Rev. Augustus Dampier, a Fellow of King’s

College, Cambridge.”

(15) “My Lord,” answered the Minister, “I will

take the furniture and the ghost at a valuation. I

come from a modern country, and I reckon that if

there were such a thing as a ghost in Europe, we’d

have it at home in a very short time in one of our

(20) public museums.”

“I fear that the ghost exists,” said Lord

Canterville, smiling, “though it may have resisted

the overtures of your enterprising impresarios.

It has been well known for three centuries, since

(25) 1584 in fact, and always makes its appearance

before the death of any member of our family.”

“Well, so does the family doctor for that

matter, Lord Canterville. But there is no such

thing, sir, as a ghost, and I guess the laws of

(30) Nature are not going to be suspended for the

British aristocracy.”

After the purchase was concluded, the

Minister and his family went down to Canterville

Chase. Mrs. Otis, who, as Miss Lucretia R. Tappan

(35) had been a celebrated New York belle, was now a

very handsome, middle-aged woman. Her eldest

son, christened Washington by his parents in a

moment of patriotism, was a fair-haired, rather

good-looking young man.

(40) Standing on the steps to receive them was old

Mrs. Umney, the housekeeper, whom Mrs. Otis, at

Lady Canterville's earnest request, had consented

to keep on in her former position. Following her

into the library, they found tea laid out for them,

(45) sat down and began to look round.

Suddenly Mrs. Otis caught sight of a dull red

stain on the floor just by the fireplace and said

to Mrs. Umney, “I am afraid something has been

spilt there.”

(50) “Yes, madam,” replied the old housekeeper in

a low voice, “blood has been spilt on that spot.”

“How horrid,” cried Mrs. Otis; “I don't at all

care for bloodstains in a sitting-room. It must be

removed at once.”

(55) The old woman answered in the same low,

mysterious voice, “It is the blood of Lady Eleanore

de Canterville, who was murdered on that spot by

her husband, Sir Simon de Canterville, in 1575.

His guilty spirit still haunts the Chase. The blood-

(60) stain has been much admired by tourists and

others, and cannot be removed.”

“That is all nonsense,” cried Washington;

“Pinkerton's Champion Stain Remover will

clean it up in no time,” and before the terrified

(65) housekeeper could interfere he was rapidly

scouring the floor. In a few moments no trace of

the blood-stain could be seen.

“I knew Pinkerton would do it,” he exclaimed

triumphantly, as he looked round at his admiring

(70) family. A terrible flash of lightning lit up the

somber room, a fearful peal of thunder made them

all start to their feet, and Mrs. Umney fainted.

“What a monstrous climate!” said the

American Minister calmly. “I guess the old

(75) country is so overpopulated that they have not

enough decent weather for everybody. I have

always been of opinion that emigration is the

only thing for England.”

“My dear Hiram,” cried Mrs. Otis, “what can

(80) we do with a woman who faints?”

“Charge it to her like breakages,” answered

the Minister; “she won't faint after that;” and in

a few moments Mrs. Umney certainly came to.

There was no doubt, however, that she was upset,

(85) and she sternly warned Mr. Otis to beware of

some trouble coming to the house.

“Many and many a night,” she said, “I have

not closed my eyes in sleep for the awful things

that are done here.” Mr. Otis, however, and his

(90) wife warmly assured the honest soul that they

were not afraid of ghosts, and, after invoking

the blessings of Providence on her new master

and mistress, and making arrangements for an

increase of salary, the old housekeeper tottered

(95) off to her own room.

Question based on the following passage.

The following passage is adapted from Oscar Wilde, The Canterville Ghost, published in 1887.

When Mr. Hiram B. Otis, the American

Minister, bought Canterville Chase, everyone

told him that the place was haunted. Indeed,

Lord Canterville himself, a man of punctilious

(5) honor, felt it his duty to mention the fact to Mr.

Otis when they came to discuss terms.

“We have not cared to live in the place

ourselves,” said Lord Canterville, “since the

Dowager Duchess of Bolton was frightened into

(10) a fit by two skeleton hands on her shoulders as

she was dressing for dinner. The ghost has been

seen by several members of my family, as well as

by the Rev. Augustus Dampier, a Fellow of King’s

College, Cambridge.”

(15) “My Lord,” answered the Minister, “I will

take the furniture and the ghost at a valuation. I

come from a modern country, and I reckon that if

there were such a thing as a ghost in Europe, we’d

have it at home in a very short time in one of our

(20) public museums.”

“I fear that the ghost exists,” said Lord

Canterville, smiling, “though it may have resisted

the overtures of your enterprising impresarios.

It has been well known for three centuries, since

(25) 1584 in fact, and always makes its appearance

before the death of any member of our family.”

“Well, so does the family doctor for that

matter, Lord Canterville. But there is no such

thing, sir, as a ghost, and I guess the laws of

(30) Nature are not going to be suspended for the

British aristocracy.”

After the purchase was concluded, the

Minister and his family went down to Canterville

Chase. Mrs. Otis, who, as Miss Lucretia R. Tappan

(35) had been a celebrated New York belle, was now a

very handsome, middle-aged woman. Her eldest

son, christened Washington by his parents in a

moment of patriotism, was a fair-haired, rather

good-looking young man.

(40) Standing on the steps to receive them was old

Mrs. Umney, the housekeeper, whom Mrs. Otis, at

Lady Canterville's earnest request, had consented

to keep on in her former position. Following her

into the library, they found tea laid out for them,

(45) sat down and began to look round.

Suddenly Mrs. Otis caught sight of a dull red

stain on the floor just by the fireplace and said

to Mrs. Umney, “I am afraid something has been

spilt there.”

(50) “Yes, madam,” replied the old housekeeper in

a low voice, “blood has been spilt on that spot.”

“How horrid,” cried Mrs. Otis; “I don't at all

care for bloodstains in a sitting-room. It must be

removed at once.”

(55) The old woman answered in the same low,

mysterious voice, “It is the blood of Lady Eleanore

de Canterville, who was murdered on that spot by

her husband, Sir Simon de Canterville, in 1575.

His guilty spirit still haunts the Chase. The blood-

(60) stain has been much admired by tourists and

others, and cannot be removed.”

“That is all nonsense,” cried Washington;

“Pinkerton's Champion Stain Remover will

clean it up in no time,” and before the terrified

(65) housekeeper could interfere he was rapidly

scouring the floor. In a few moments no trace of

the blood-stain could be seen.

“I knew Pinkerton would do it,” he exclaimed

triumphantly, as he looked round at his admiring

(70) family. A terrible flash of lightning lit up the

somber room, a fearful peal of thunder made them

all start to their feet, and Mrs. Umney fainted.

“What a monstrous climate!” said the

American Minister calmly. “I guess the old

(75) country is so overpopulated that they have not

enough decent weather for everybody. I have

always been of opinion that emigration is the

only thing for England.”

“My dear Hiram,” cried Mrs. Otis, “what can

(80) we do with a woman who faints?”

“Charge it to her like breakages,” answered

the Minister; “she won't faint after that;” and in

a few moments Mrs. Umney certainly came to.

There was no doubt, however, that she was upset,

(85) and she sternly warned Mr. Otis to beware of

some trouble coming to the house.

“Many and many a night,” she said, “I have

not closed my eyes in sleep for the awful things

that are done here.” Mr. Otis, however, and his

(90) wife warmly assured the honest soul that they

were not afraid of ghosts, and, after invoking

the blessings of Providence on her new master

and mistress, and making arrangements for an

increase of salary, the old housekeeper tottered

(95) off to her own room.

Q. Which choice best describes the tone and developmental pattern of the passage?

The following passage is adapted from Oscar Wilde, The Canterville Ghost, published in 1887.

When Mr. Hiram B. Otis, the American

Minister, bought Canterville Chase, everyone

told him that the place was haunted. Indeed,

Lord Canterville himself, a man of punctilious

(5) honor, felt it his duty to mention the fact to Mr.

Otis when they came to discuss terms.

“We have not cared to live in the place

ourselves,” said Lord Canterville, “since the

Dowager Duchess of Bolton was frightened into

(10) a fit by two skeleton hands on her shoulders as

she was dressing for dinner. The ghost has been

seen by several members of my family, as well as

by the Rev. Augustus Dampier, a Fellow of King’s

College, Cambridge.”

(15) “My Lord,” answered the Minister, “I will

take the furniture and the ghost at a valuation. I

come from a modern country, and I reckon that if

there were such a thing as a ghost in Europe, we’d

have it at home in a very short time in one of our

(20) public museums.”

“I fear that the ghost exists,” said Lord

Canterville, smiling, “though it may have resisted

the overtures of your enterprising impresarios.

It has been well known for three centuries, since

(25) 1584 in fact, and always makes its appearance

before the death of any member of our family.”

“Well, so does the family doctor for that

matter, Lord Canterville. But there is no such

thing, sir, as a ghost, and I guess the laws of

(30) Nature are not going to be suspended for the

British aristocracy.”

After the purchase was concluded, the

Minister and his family went down to Canterville

Chase. Mrs. Otis, who, as Miss Lucretia R. Tappan

(35) had been a celebrated New York belle, was now a

very handsome, middle-aged woman. Her eldest

son, christened Washington by his parents in a

moment of patriotism, was a fair-haired, rather

good-looking young man.

(40) Standing on the steps to receive them was old

Mrs. Umney, the housekeeper, whom Mrs. Otis, at

Lady Canterville's earnest request, had consented

to keep on in her former position. Following her

into the library, they found tea laid out for them,

(45) sat down and began to look round.

Suddenly Mrs. Otis caught sight of a dull red

stain on the floor just by the fireplace and said

to Mrs. Umney, “I am afraid something has been

spilt there.”

(50) “Yes, madam,” replied the old housekeeper in

a low voice, “blood has been spilt on that spot.”

“How horrid,” cried Mrs. Otis; “I don't at all

care for bloodstains in a sitting-room. It must be

removed at once.”

(55) The old woman answered in the same low,

mysterious voice, “It is the blood of Lady Eleanore

de Canterville, who was murdered on that spot by

her husband, Sir Simon de Canterville, in 1575.

His guilty spirit still haunts the Chase. The blood-

(60) stain has been much admired by tourists and

others, and cannot be removed.”

“That is all nonsense,” cried Washington;

“Pinkerton's Champion Stain Remover will

clean it up in no time,” and before the terrified

(65) housekeeper could interfere he was rapidly

scouring the floor. In a few moments no trace of

the blood-stain could be seen.

“I knew Pinkerton would do it,” he exclaimed

triumphantly, as he looked round at his admiring

(70) family. A terrible flash of lightning lit up the

somber room, a fearful peal of thunder made them

all start to their feet, and Mrs. Umney fainted.

“What a monstrous climate!” said the

American Minister calmly. “I guess the old

(75) country is so overpopulated that they have not

enough decent weather for everybody. I have

always been of opinion that emigration is the

only thing for England.”

“My dear Hiram,” cried Mrs. Otis, “what can

(80) we do with a woman who faints?”

“Charge it to her like breakages,” answered

the Minister; “she won't faint after that;” and in

a few moments Mrs. Umney certainly came to.

There was no doubt, however, that she was upset,

(85) and she sternly warned Mr. Otis to beware of

some trouble coming to the house.

“Many and many a night,” she said, “I have

not closed my eyes in sleep for the awful things

that are done here.” Mr. Otis, however, and his

(90) wife warmly assured the honest soul that they

were not afraid of ghosts, and, after invoking

the blessings of Providence on her new master

and mistress, and making arrangements for an

increase of salary, the old housekeeper tottered

(95) off to her own room.

Question based on the following passage.

The following passage is adapted from Oscar Wilde, The Canterville Ghost, published in 1887.

When Mr. Hiram B. Otis, the American

Minister, bought Canterville Chase, everyone

told him that the place was haunted. Indeed,

Lord Canterville himself, a man of punctilious

(5) honor, felt it his duty to mention the fact to Mr.

Otis when they came to discuss terms.

“We have not cared to live in the place

ourselves,” said Lord Canterville, “since the

Dowager Duchess of Bolton was frightened into

(10) a fit by two skeleton hands on her shoulders as

she was dressing for dinner. The ghost has been

seen by several members of my family, as well as

by the Rev. Augustus Dampier, a Fellow of King’s

College, Cambridge.”

(15) “My Lord,” answered the Minister, “I will

take the furniture and the ghost at a valuation. I

come from a modern country, and I reckon that if

there were such a thing as a ghost in Europe, we’d

have it at home in a very short time in one of our

(20) public museums.”

“I fear that the ghost exists,” said Lord

Canterville, smiling, “though it may have resisted

the overtures of your enterprising impresarios.

It has been well known for three centuries, since

(25) 1584 in fact, and always makes its appearance

before the death of any member of our family.”

“Well, so does the family doctor for that

matter, Lord Canterville. But there is no such

thing, sir, as a ghost, and I guess the laws of

(30) Nature are not going to be suspended for the

British aristocracy.”

After the purchase was concluded, the

Minister and his family went down to Canterville

Chase. Mrs. Otis, who, as Miss Lucretia R. Tappan

(35) had been a celebrated New York belle, was now a

very handsome, middle-aged woman. Her eldest

son, christened Washington by his parents in a

moment of patriotism, was a fair-haired, rather

good-looking young man.

(40) Standing on the steps to receive them was old

Mrs. Umney, the housekeeper, whom Mrs. Otis, at

Lady Canterville's earnest request, had consented

to keep on in her former position. Following her

into the library, they found tea laid out for them,

(45) sat down and began to look round.

Suddenly Mrs. Otis caught sight of a dull red

stain on the floor just by the fireplace and said

to Mrs. Umney, “I am afraid something has been

spilt there.”

(50) “Yes, madam,” replied the old housekeeper in

a low voice, “blood has been spilt on that spot.”

“How horrid,” cried Mrs. Otis; “I don't at all

care for bloodstains in a sitting-room. It must be

removed at once.”

(55) The old woman answered in the same low,

mysterious voice, “It is the blood of Lady Eleanore

de Canterville, who was murdered on that spot by

her husband, Sir Simon de Canterville, in 1575.

His guilty spirit still haunts the Chase. The blood-

(60) stain has been much admired by tourists and

others, and cannot be removed.”

“That is all nonsense,” cried Washington;

“Pinkerton's Champion Stain Remover will

clean it up in no time,” and before the terrified

(65) housekeeper could interfere he was rapidly

scouring the floor. In a few moments no trace of

the blood-stain could be seen.

“I knew Pinkerton would do it,” he exclaimed

triumphantly, as he looked round at his admiring

(70) family. A terrible flash of lightning lit up the

somber room, a fearful peal of thunder made them

all start to their feet, and Mrs. Umney fainted.

“What a monstrous climate!” said the

American Minister calmly. “I guess the old

(75) country is so overpopulated that they have not

enough decent weather for everybody. I have

always been of opinion that emigration is the

only thing for England.”

“My dear Hiram,” cried Mrs. Otis, “what can

(80) we do with a woman who faints?”

“Charge it to her like breakages,” answered

the Minister; “she won't faint after that;” and in

a few moments Mrs. Umney certainly came to.

There was no doubt, however, that she was upset,

(85) and she sternly warned Mr. Otis to beware of

some trouble coming to the house.

“Many and many a night,” she said, “I have

not closed my eyes in sleep for the awful things

that are done here.” Mr. Otis, however, and his

(90) wife warmly assured the honest soul that they

were not afraid of ghosts, and, after invoking

the blessings of Providence on her new master

and mistress, and making arrangements for an

increase of salary, the old housekeeper tottered

(95) off to her own room.

Q. Lord Canterville mentions the titles of Augustus Dampier in line 13 in order to emphasize

The following passage is adapted from Oscar Wilde, The Canterville Ghost, published in 1887.

When Mr. Hiram B. Otis, the American

Minister, bought Canterville Chase, everyone

told him that the place was haunted. Indeed,

Lord Canterville himself, a man of punctilious

(5) honor, felt it his duty to mention the fact to Mr.

Otis when they came to discuss terms.

“We have not cared to live in the place

ourselves,” said Lord Canterville, “since the

Dowager Duchess of Bolton was frightened into

(10) a fit by two skeleton hands on her shoulders as

she was dressing for dinner. The ghost has been

seen by several members of my family, as well as

by the Rev. Augustus Dampier, a Fellow of King’s

College, Cambridge.”

(15) “My Lord,” answered the Minister, “I will

take the furniture and the ghost at a valuation. I

come from a modern country, and I reckon that if

there were such a thing as a ghost in Europe, we’d

have it at home in a very short time in one of our

(20) public museums.”

“I fear that the ghost exists,” said Lord

Canterville, smiling, “though it may have resisted

the overtures of your enterprising impresarios.

It has been well known for three centuries, since

(25) 1584 in fact, and always makes its appearance

before the death of any member of our family.”

“Well, so does the family doctor for that

matter, Lord Canterville. But there is no such

thing, sir, as a ghost, and I guess the laws of

(30) Nature are not going to be suspended for the

British aristocracy.”

After the purchase was concluded, the

Minister and his family went down to Canterville

Chase. Mrs. Otis, who, as Miss Lucretia R. Tappan

(35) had been a celebrated New York belle, was now a

very handsome, middle-aged woman. Her eldest

son, christened Washington by his parents in a

moment of patriotism, was a fair-haired, rather

good-looking young man.

(40) Standing on the steps to receive them was old

Mrs. Umney, the housekeeper, whom Mrs. Otis, at

Lady Canterville's earnest request, had consented

to keep on in her former position. Following her

into the library, they found tea laid out for them,

(45) sat down and began to look round.

Suddenly Mrs. Otis caught sight of a dull red

stain on the floor just by the fireplace and said

to Mrs. Umney, “I am afraid something has been

spilt there.”

(50) “Yes, madam,” replied the old housekeeper in

a low voice, “blood has been spilt on that spot.”

“How horrid,” cried Mrs. Otis; “I don't at all

care for bloodstains in a sitting-room. It must be

removed at once.”

(55) The old woman answered in the same low,

mysterious voice, “It is the blood of Lady Eleanore

de Canterville, who was murdered on that spot by

her husband, Sir Simon de Canterville, in 1575.

His guilty spirit still haunts the Chase. The blood-

(60) stain has been much admired by tourists and

others, and cannot be removed.”

“That is all nonsense,” cried Washington;

“Pinkerton's Champion Stain Remover will

clean it up in no time,” and before the terrified

(65) housekeeper could interfere he was rapidly

scouring the floor. In a few moments no trace of

the blood-stain could be seen.

“I knew Pinkerton would do it,” he exclaimed

triumphantly, as he looked round at his admiring

(70) family. A terrible flash of lightning lit up the

somber room, a fearful peal of thunder made them

all start to their feet, and Mrs. Umney fainted.

“What a monstrous climate!” said the

American Minister calmly. “I guess the old

(75) country is so overpopulated that they have not

enough decent weather for everybody. I have

always been of opinion that emigration is the

only thing for England.”

“My dear Hiram,” cried Mrs. Otis, “what can

(80) we do with a woman who faints?”

“Charge it to her like breakages,” answered

the Minister; “she won't faint after that;” and in

a few moments Mrs. Umney certainly came to.

There was no doubt, however, that she was upset,

(85) and she sternly warned Mr. Otis to beware of

some trouble coming to the house.

“Many and many a night,” she said, “I have

not closed my eyes in sleep for the awful things

that are done here.” Mr. Otis, however, and his

(90) wife warmly assured the honest soul that they

were not afraid of ghosts, and, after invoking

the blessings of Providence on her new master

and mistress, and making arrangements for an

increase of salary, the old housekeeper tottered

(95) off to her own room.

Question based on the following passage.

The following passage is adapted from Oscar Wilde, The Canterville Ghost, published in 1887.

When Mr. Hiram B. Otis, the American

Minister, bought Canterville Chase, everyone

told him that the place was haunted. Indeed,

Lord Canterville himself, a man of punctilious

(5) honor, felt it his duty to mention the fact to Mr.

Otis when they came to discuss terms.

“We have not cared to live in the place

ourselves,” said Lord Canterville, “since the

Dowager Duchess of Bolton was frightened into

(10) a fit by two skeleton hands on her shoulders as

she was dressing for dinner. The ghost has been

seen by several members of my family, as well as

by the Rev. Augustus Dampier, a Fellow of King’s

College, Cambridge.”

(15) “My Lord,” answered the Minister, “I will

take the furniture and the ghost at a valuation. I

come from a modern country, and I reckon that if

there were such a thing as a ghost in Europe, we’d

have it at home in a very short time in one of our

(20) public museums.”

“I fear that the ghost exists,” said Lord

Canterville, smiling, “though it may have resisted

the overtures of your enterprising impresarios.

It has been well known for three centuries, since

(25) 1584 in fact, and always makes its appearance

before the death of any member of our family.”

“Well, so does the family doctor for that

matter, Lord Canterville. But there is no such

thing, sir, as a ghost, and I guess the laws of

(30) Nature are not going to be suspended for the

British aristocracy.”

After the purchase was concluded, the

Minister and his family went down to Canterville

Chase. Mrs. Otis, who, as Miss Lucretia R. Tappan

(35) had been a celebrated New York belle, was now a

very handsome, middle-aged woman. Her eldest

son, christened Washington by his parents in a

moment of patriotism, was a fair-haired, rather

good-looking young man.

(40) Standing on the steps to receive them was old

Mrs. Umney, the housekeeper, whom Mrs. Otis, at

Lady Canterville's earnest request, had consented

to keep on in her former position. Following her

into the library, they found tea laid out for them,

(45) sat down and began to look round.

Suddenly Mrs. Otis caught sight of a dull red

stain on the floor just by the fireplace and said

to Mrs. Umney, “I am afraid something has been

spilt there.”

(50) “Yes, madam,” replied the old housekeeper in

a low voice, “blood has been spilt on that spot.”

“How horrid,” cried Mrs. Otis; “I don't at all

care for bloodstains in a sitting-room. It must be

removed at once.”

(55) The old woman answered in the same low,

mysterious voice, “It is the blood of Lady Eleanore

de Canterville, who was murdered on that spot by

her husband, Sir Simon de Canterville, in 1575.

His guilty spirit still haunts the Chase. The blood-

(60) stain has been much admired by tourists and

others, and cannot be removed.”

“That is all nonsense,” cried Washington;

“Pinkerton's Champion Stain Remover will

clean it up in no time,” and before the terrified

(65) housekeeper could interfere he was rapidly

scouring the floor. In a few moments no trace of

the blood-stain could be seen.

“I knew Pinkerton would do it,” he exclaimed

triumphantly, as he looked round at his admiring

(70) family. A terrible flash of lightning lit up the

somber room, a fearful peal of thunder made them

all start to their feet, and Mrs. Umney fainted.

“What a monstrous climate!” said the

American Minister calmly. “I guess the old

(75) country is so overpopulated that they have not

enough decent weather for everybody. I have

always been of opinion that emigration is the

only thing for England.”

“My dear Hiram,” cried Mrs. Otis, “what can

(80) we do with a woman who faints?”

“Charge it to her like breakages,” answered

the Minister; “she won't faint after that;” and in

a few moments Mrs. Umney certainly came to.

There was no doubt, however, that she was upset,

(85) and she sternly warned Mr. Otis to beware of

some trouble coming to the house.

“Many and many a night,” she said, “I have

not closed my eyes in sleep for the awful things

that are done here.” Mr. Otis, however, and his

(90) wife warmly assured the honest soul that they

were not afraid of ghosts, and, after invoking

the blessings of Providence on her new master

and mistress, and making arrangements for an

increase of salary, the old housekeeper tottered

(95) off to her own room.

Q. As used in line 30, “suspended” most nearly means

Question based on the following passage.

The following passage is adapted from Oscar Wilde, The Canterville Ghost, published in 1887.

When Mr. Hiram B. Otis, the American

Minister, bought Canterville Chase, everyone

told him that the place was haunted. Indeed,

Lord Canterville himself, a man of punctilious

(5) honor, felt it his duty to mention the fact to Mr.

Otis when they came to discuss terms.

“We have not cared to live in the place

ourselves,” said Lord Canterville, “since the

Dowager Duchess of Bolton was frightened into

(10) a fit by two skeleton hands on her shoulders as

she was dressing for dinner. The ghost has been

seen by several members of my family, as well as

by the Rev. Augustus Dampier, a Fellow of King’s

College, Cambridge.”

(15) “My Lord,” answered the Minister, “I will

take the furniture and the ghost at a valuation. I

come from a modern country, and I reckon that if

there were such a thing as a ghost in Europe, we’d

have it at home in a very short time in one of our

(20) public museums.”

“I fear that the ghost exists,” said Lord

Canterville, smiling, “though it may have resisted

the overtures of your enterprising impresarios.

It has been well known for three centuries, since

(25) 1584 in fact, and always makes its appearance

before the death of any member of our family.”

“Well, so does the family doctor for that

matter, Lord Canterville. But there is no such

thing, sir, as a ghost, and I guess the laws of

(30) Nature are not going to be suspended for the

British aristocracy.”

After the purchase was concluded, the

Minister and his family went down to Canterville

Chase. Mrs. Otis, who, as Miss Lucretia R. Tappan

(35) had been a celebrated New York belle, was now a

very handsome, middle-aged woman. Her eldest

son, christened Washington by his parents in a

moment of patriotism, was a fair-haired, rather

good-looking young man.

(40) Standing on the steps to receive them was old

Mrs. Umney, the housekeeper, whom Mrs. Otis, at

Lady Canterville's earnest request, had consented

to keep on in her former position. Following her

into the library, they found tea laid out for them,

(45) sat down and began to look round.

Suddenly Mrs. Otis caught sight of a dull red

stain on the floor just by the fireplace and said

to Mrs. Umney, “I am afraid something has been

spilt there.”

(50) “Yes, madam,” replied the old housekeeper in

a low voice, “blood has been spilt on that spot.”

“How horrid,” cried Mrs. Otis; “I don't at all

care for bloodstains in a sitting-room. It must be

removed at once.”

(55) The old woman answered in the same low,

mysterious voice, “It is the blood of Lady Eleanore

de Canterville, who was murdered on that spot by

her husband, Sir Simon de Canterville, in 1575.

His guilty spirit still haunts the Chase. The blood-

(60) stain has been much admired by tourists and

others, and cannot be removed.”

“That is all nonsense,” cried Washington;

“Pinkerton's Champion Stain Remover will

clean it up in no time,” and before the terrified

(65) housekeeper could interfere he was rapidly

scouring the floor. In a few moments no trace of

the blood-stain could be seen.

“I knew Pinkerton would do it,” he exclaimed

triumphantly, as he looked round at his admiring

(70) family. A terrible flash of lightning lit up the

somber room, a fearful peal of thunder made them

all start to their feet, and Mrs. Umney fainted.

“What a monstrous climate!” said the

American Minister calmly. “I guess the old

(75) country is so overpopulated that they have not

enough decent weather for everybody. I have

always been of opinion that emigration is the

only thing for England.”

“My dear Hiram,” cried Mrs. Otis, “what can

(80) we do with a woman who faints?”

“Charge it to her like breakages,” answered

the Minister; “she won't faint after that;” and in

a few moments Mrs. Umney certainly came to.

There was no doubt, however, that she was upset,

(85) and she sternly warned Mr. Otis to beware of

some trouble coming to the house.

“Many and many a night,” she said, “I have

not closed my eyes in sleep for the awful things

that are done here.” Mr. Otis, however, and his

(90) wife warmly assured the honest soul that they

were not afraid of ghosts, and, after invoking

the blessings of Providence on her new master

and mistress, and making arrangements for an

increase of salary, the old housekeeper tottered

(95) off to her own room.

Q. The Otises regard the blood stain in the library as

Question based on the following passage.

The following passage is adapted from Oscar Wilde, The Canterville Ghost, published in 1887.

When Mr. Hiram B. Otis, the American

Minister, bought Canterville Chase, everyone

told him that the place was haunted. Indeed,

Lord Canterville himself, a man of punctilious

(5) honor, felt it his duty to mention the fact to Mr.

Otis when they came to discuss terms.

“We have not cared to live in the place

ourselves,” said Lord Canterville, “since the

Dowager Duchess of Bolton was frightened into

(10) a fit by two skeleton hands on her shoulders as

she was dressing for dinner. The ghost has been

seen by several members of my family, as well as

by the Rev. Augustus Dampier, a Fellow of King’s

College, Cambridge.”

(15) “My Lord,” answered the Minister, “I will

take the furniture and the ghost at a valuation. I

come from a modern country, and I reckon that if

there were such a thing as a ghost in Europe, we’d

have it at home in a very short time in one of our

(20) public museums.”

“I fear that the ghost exists,” said Lord

Canterville, smiling, “though it may have resisted

the overtures of your enterprising impresarios.

It has been well known for three centuries, since

(25) 1584 in fact, and always makes its appearance

before the death of any member of our family.”

“Well, so does the family doctor for that

matter, Lord Canterville. But there is no such

thing, sir, as a ghost, and I guess the laws of

(30) Nature are not going to be suspended for the

British aristocracy.”

After the purchase was concluded, the

Minister and his family went down to Canterville

Chase. Mrs. Otis, who, as Miss Lucretia R. Tappan

(35) had been a celebrated New York belle, was now a

very handsome, middle-aged woman. Her eldest

son, christened Washington by his parents in a

moment of patriotism, was a fair-haired, rather

good-looking young man.

(40) Standing on the steps to receive them was old

Mrs. Umney, the housekeeper, whom Mrs. Otis, at

Lady Canterville's earnest request, had consented

to keep on in her former position. Following her

into the library, they found tea laid out for them,

(45) sat down and began to look round.

Suddenly Mrs. Otis caught sight of a dull red

stain on the floor just by the fireplace and said

to Mrs. Umney, “I am afraid something has been

spilt there.”

(50) “Yes, madam,” replied the old housekeeper in

a low voice, “blood has been spilt on that spot.”

“How horrid,” cried Mrs. Otis; “I don't at all

care for bloodstains in a sitting-room. It must be

removed at once.”

(55) The old woman answered in the same low,

mysterious voice, “It is the blood of Lady Eleanore

de Canterville, who was murdered on that spot by

her husband, Sir Simon de Canterville, in 1575.

His guilty spirit still haunts the Chase. The blood-

(60) stain has been much admired by tourists and

others, and cannot be removed.”

“That is all nonsense,” cried Washington;

“Pinkerton's Champion Stain Remover will

clean it up in no time,” and before the terrified

(65) housekeeper could interfere he was rapidly

scouring the floor. In a few moments no trace of

the blood-stain could be seen.

“I knew Pinkerton would do it,” he exclaimed

triumphantly, as he looked round at his admiring

(70) family. A terrible flash of lightning lit up the

somber room, a fearful peal of thunder made them

all start to their feet, and Mrs. Umney fainted.

“What a monstrous climate!” said the

American Minister calmly. “I guess the old

(75) country is so overpopulated that they have not

enough decent weather for everybody. I have

always been of opinion that emigration is the

only thing for England.”

“My dear Hiram,” cried Mrs. Otis, “what can

(80) we do with a woman who faints?”

“Charge it to her like breakages,” answered

the Minister; “she won't faint after that;” and in

a few moments Mrs. Umney certainly came to.

There was no doubt, however, that she was upset,

(85) and she sternly warned Mr. Otis to beware of

some trouble coming to the house.

“Many and many a night,” she said, “I have

not closed my eyes in sleep for the awful things

that are done here.” Mr. Otis, however, and his

(90) wife warmly assured the honest soul that they

were not afraid of ghosts, and, after invoking

the blessings of Providence on her new master

and mistress, and making arrangements for an

increase of salary, the old housekeeper tottered

(95) off to her own room.

Q. Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

Question based on the following passage.

The following passage is adapted from Oscar Wilde, The Canterville Ghost, published in 1887.

When Mr. Hiram B. Otis, the American

Minister, bought Canterville Chase, everyone

told him that the place was haunted. Indeed,

Lord Canterville himself, a man of punctilious

(5) honor, felt it his duty to mention the fact to Mr.

Otis when they came to discuss terms.

“We have not cared to live in the place

ourselves,” said Lord Canterville, “since the

Dowager Duchess of Bolton was frightened into

(10) a fit by two skeleton hands on her shoulders as

she was dressing for dinner. The ghost has been

seen by several members of my family, as well as

by the Rev. Augustus Dampier, a Fellow of King’s

College, Cambridge.”

(15) “My Lord,” answered the Minister, “I will

take the furniture and the ghost at a valuation. I

come from a modern country, and I reckon that if

there were such a thing as a ghost in Europe, we’d

have it at home in a very short time in one of our

(20) public museums.”

“I fear that the ghost exists,” said Lord

Canterville, smiling, “though it may have resisted

the overtures of your enterprising impresarios.

It has been well known for three centuries, since

(25) 1584 in fact, and always makes its appearance

before the death of any member of our family.”

“Well, so does the family doctor for that

matter, Lord Canterville. But there is no such

thing, sir, as a ghost, and I guess the laws of

(30) Nature are not going to be suspended for the

British aristocracy.”

After the purchase was concluded, the

Minister and his family went down to Canterville

Chase. Mrs. Otis, who, as Miss Lucretia R. Tappan

(35) had been a celebrated New York belle, was now a

very handsome, middle-aged woman. Her eldest

son, christened Washington by his parents in a

moment of patriotism, was a fair-haired, rather

good-looking young man.

(40) Standing on the steps to receive them was old

Mrs. Umney, the housekeeper, whom Mrs. Otis, at

Lady Canterville's earnest request, had consented

to keep on in her former position. Following her

into the library, they found tea laid out for them,

(45) sat down and began to look round.

Suddenly Mrs. Otis caught sight of a dull red

stain on the floor just by the fireplace and said

to Mrs. Umney, “I am afraid something has been

spilt there.”

(50) “Yes, madam,” replied the old housekeeper in

a low voice, “blood has been spilt on that spot.”

“How horrid,” cried Mrs. Otis; “I don't at all

care for bloodstains in a sitting-room. It must be

removed at once.”

(55) The old woman answered in the same low,

mysterious voice, “It is the blood of Lady Eleanore

de Canterville, who was murdered on that spot by

her husband, Sir Simon de Canterville, in 1575.

His guilty spirit still haunts the Chase. The blood-

(60) stain has been much admired by tourists and

others, and cannot be removed.”

“That is all nonsense,” cried Washington;

“Pinkerton's Champion Stain Remover will

clean it up in no time,” and before the terrified

(65) housekeeper could interfere he was rapidly

scouring the floor. In a few moments no trace of

the blood-stain could be seen.

“I knew Pinkerton would do it,” he exclaimed

triumphantly, as he looked round at his admiring

(70) family. A terrible flash of lightning lit up the

somber room, a fearful peal of thunder made them

all start to their feet, and Mrs. Umney fainted.

“What a monstrous climate!” said the

American Minister calmly. “I guess the old

(75) country is so overpopulated that they have not

enough decent weather for everybody. I have

always been of opinion that emigration is the

only thing for England.”

“My dear Hiram,” cried Mrs. Otis, “what can

(80) we do with a woman who faints?”

“Charge it to her like breakages,” answered

the Minister; “she won't faint after that;” and in

a few moments Mrs. Umney certainly came to.

There was no doubt, however, that she was upset,

(85) and she sternly warned Mr. Otis to beware of

some trouble coming to the house.

“Many and many a night,” she said, “I have

not closed my eyes in sleep for the awful things

that are done here.” Mr. Otis, however, and his

(90) wife warmly assured the honest soul that they

were not afraid of ghosts, and, after invoking

the blessings of Providence on her new master

and mistress, and making arrangements for an

increase of salary, the old housekeeper tottered

(95) off to her own room.

Q. As used in line 72, “start” most nearly means

Question based on the following passage.

The following passage is adapted from Oscar Wilde, The Canterville Ghost, published in 1887.

When Mr. Hiram B. Otis, the American

Minister, bought Canterville Chase, everyone

told him that the place was haunted. Indeed,

Lord Canterville himself, a man of punctilious

(5) honor, felt it his duty to mention the fact to Mr.

Otis when they came to discuss terms.

“We have not cared to live in the place

ourselves,” said Lord Canterville, “since the

Dowager Duchess of Bolton was frightened into

(10) a fit by two skeleton hands on her shoulders as

she was dressing for dinner. The ghost has been

seen by several members of my family, as well as

by the Rev. Augustus Dampier, a Fellow of King’s

College, Cambridge.”

(15) “My Lord,” answered the Minister, “I will

take the furniture and the ghost at a valuation. I

come from a modern country, and I reckon that if

there were such a thing as a ghost in Europe, we’d

have it at home in a very short time in one of our

(20) public museums.”

“I fear that the ghost exists,” said Lord

Canterville, smiling, “though it may have resisted

the overtures of your enterprising impresarios.

It has been well known for three centuries, since

(25) 1584 in fact, and always makes its appearance

before the death of any member of our family.”

“Well, so does the family doctor for that

matter, Lord Canterville. But there is no such

thing, sir, as a ghost, and I guess the laws of

(30) Nature are not going to be suspended for the

British aristocracy.”

After the purchase was concluded, the

Minister and his family went down to Canterville

Chase. Mrs. Otis, who, as Miss Lucretia R. Tappan

(35) had been a celebrated New York belle, was now a

very handsome, middle-aged woman. Her eldest

son, christened Washington by his parents in a

moment of patriotism, was a fair-haired, rather

good-looking young man.

(40) Standing on the steps to receive them was old

Mrs. Umney, the housekeeper, whom Mrs. Otis, at

Lady Canterville's earnest request, had consented

to keep on in her former position. Following her

into the library, they found tea laid out for them,

(45) sat down and began to look round.

Suddenly Mrs. Otis caught sight of a dull red

stain on the floor just by the fireplace and said

to Mrs. Umney, “I am afraid something has been

spilt there.”

(50) “Yes, madam,” replied the old housekeeper in

a low voice, “blood has been spilt on that spot.”

“How horrid,” cried Mrs. Otis; “I don't at all

care for bloodstains in a sitting-room. It must be

removed at once.”

(55) The old woman answered in the same low,

mysterious voice, “It is the blood of Lady Eleanore

de Canterville, who was murdered on that spot by

her husband, Sir Simon de Canterville, in 1575.

His guilty spirit still haunts the Chase. The blood-

(60) stain has been much admired by tourists and

others, and cannot be removed.”

“That is all nonsense,” cried Washington;

“Pinkerton's Champion Stain Remover will

clean it up in no time,” and before the terrified

(65) housekeeper could interfere he was rapidly

scouring the floor. In a few moments no trace of

the blood-stain could be seen.

“I knew Pinkerton would do it,” he exclaimed

triumphantly, as he looked round at his admiring

(70) family. A terrible flash of lightning lit up the

somber room, a fearful peal of thunder made them

all start to their feet, and Mrs. Umney fainted.

“What a monstrous climate!” said the

American Minister calmly. “I guess the old

(75) country is so overpopulated that they have not

enough decent weather for everybody. I have

always been of opinion that emigration is the

only thing for England.”

“My dear Hiram,” cried Mrs. Otis, “what can

(80) we do with a woman who faints?”

“Charge it to her like breakages,” answered

the Minister; “she won't faint after that;” and in

a few moments Mrs. Umney certainly came to.

There was no doubt, however, that she was upset,

(85) and she sternly warned Mr. Otis to beware of

some trouble coming to the house.

“Many and many a night,” she said, “I have

not closed my eyes in sleep for the awful things

that are done here.” Mr. Otis, however, and his

(90) wife warmly assured the honest soul that they

were not afraid of ghosts, and, after invoking

the blessings of Providence on her new master

and mistress, and making arrangements for an

increase of salary, the old housekeeper tottered

(95) off to her own room.

Q. The conversation between Mr. and Mrs. Otis in lines 73–80 is notable for its tone of

Question based on the following passage.

The following passage is adapted from Oscar Wilde, The Canterville Ghost, published in 1887.

When Mr. Hiram B. Otis, the American

Minister, bought Canterville Chase, everyone

told him that the place was haunted. Indeed,

Lord Canterville himself, a man of punctilious

(5) honor, felt it his duty to mention the fact to Mr.

Otis when they came to discuss terms.

“We have not cared to live in the place

ourselves,” said Lord Canterville, “since the

Dowager Duchess of Bolton was frightened into

(10) a fit by two skeleton hands on her shoulders as

she was dressing for dinner. The ghost has been

seen by several members of my family, as well as

by the Rev. Augustus Dampier, a Fellow of King’s

College, Cambridge.”

(15) “My Lord,” answered the Minister, “I will

take the furniture and the ghost at a valuation. I

come from a modern country, and I reckon that if

there were such a thing as a ghost in Europe, we’d

have it at home in a very short time in one of our

(20) public museums.”

“I fear that the ghost exists,” said Lord

Canterville, smiling, “though it may have resisted

the overtures of your enterprising impresarios.

It has been well known for three centuries, since

(25) 1584 in fact, and always makes its appearance

before the death of any member of our family.”

“Well, so does the family doctor for that

matter, Lord Canterville. But there is no such

thing, sir, as a ghost, and I guess the laws of

(30) Nature are not going to be suspended for the

British aristocracy.”

After the purchase was concluded, the

Minister and his family went down to Canterville

Chase. Mrs. Otis, who, as Miss Lucretia R. Tappan

(35) had been a celebrated New York belle, was now a

very handsome, middle-aged woman. Her eldest

son, christened Washington by his parents in a

moment of patriotism, was a fair-haired, rather

good-looking young man.

(40) Standing on the steps to receive them was old

Mrs. Umney, the housekeeper, whom Mrs. Otis, at

Lady Canterville's earnest request, had consented

to keep on in her former position. Following her

into the library, they found tea laid out for them,

(45) sat down and began to look round.

Suddenly Mrs. Otis caught sight of a dull red

stain on the floor just by the fireplace and said

to Mrs. Umney, “I am afraid something has been

spilt there.”

(50) “Yes, madam,” replied the old housekeeper in

a low voice, “blood has been spilt on that spot.”

“How horrid,” cried Mrs. Otis; “I don't at all

care for bloodstains in a sitting-room. It must be

removed at once.”

(55) The old woman answered in the same low,

mysterious voice, “It is the blood of Lady Eleanore

de Canterville, who was murdered on that spot by

her husband, Sir Simon de Canterville, in 1575.

His guilty spirit still haunts the Chase. The blood-

(60) stain has been much admired by tourists and

others, and cannot be removed.”

“That is all nonsense,” cried Washington;

“Pinkerton's Champion Stain Remover will

clean it up in no time,” and before the terrified

(65) housekeeper could interfere he was rapidly

scouring the floor. In a few moments no trace of

the blood-stain could be seen.

“I knew Pinkerton would do it,” he exclaimed

triumphantly, as he looked round at his admiring

(70) family. A terrible flash of lightning lit up the

somber room, a fearful peal of thunder made them

all start to their feet, and Mrs. Umney fainted.

“What a monstrous climate!” said the

American Minister calmly. “I guess the old

(75) country is so overpopulated that they have not

enough decent weather for everybody. I have

always been of opinion that emigration is the

only thing for England.”

“My dear Hiram,” cried Mrs. Otis, “what can

(80) we do with a woman who faints?”

“Charge it to her like breakages,” answered

the Minister; “she won't faint after that;” and in

a few moments Mrs. Umney certainly came to.

There was no doubt, however, that she was upset,

(85) and she sternly warned Mr. Otis to beware of

some trouble coming to the house.

“Many and many a night,” she said, “I have

not closed my eyes in sleep for the awful things

that are done here.” Mr. Otis, however, and his

(90) wife warmly assured the honest soul that they

were not afraid of ghosts, and, after invoking

the blessings of Providence on her new master

and mistress, and making arrangements for an

increase of salary, the old housekeeper tottered

(95) off to her own room.

Q. Mr. Otis dismisses the claims that Canterville Chase is haunted because

Question based on the following passage.

The following passage is adapted from Oscar Wilde, The Canterville Ghost, published in 1887.

When Mr. Hiram B. Otis, the American

Minister, bought Canterville Chase, everyone

told him that the place was haunted. Indeed,

Lord Canterville himself, a man of punctilious

(5) honor, felt it his duty to mention the fact to Mr.

Otis when they came to discuss terms.

“We have not cared to live in the place

ourselves,” said Lord Canterville, “since the

Dowager Duchess of Bolton was frightened into

(10) a fit by two skeleton hands on her shoulders as

she was dressing for dinner. The ghost has been

seen by several members of my family, as well as

by the Rev. Augustus Dampier, a Fellow of King’s

College, Cambridge.”

(15) “My Lord,” answered the Minister, “I will

take the furniture and the ghost at a valuation. I

come from a modern country, and I reckon that if

there were such a thing as a ghost in Europe, we’d

have it at home in a very short time in one of our

(20) public museums.”

“I fear that the ghost exists,” said Lord

Canterville, smiling, “though it may have resisted

the overtures of your enterprising impresarios.

It has been well known for three centuries, since

(25) 1584 in fact, and always makes its appearance

before the death of any member of our family.”

“Well, so does the family doctor for that

matter, Lord Canterville. But there is no such

thing, sir, as a ghost, and I guess the laws of

(30) Nature are not going to be suspended for the

British aristocracy.”

After the purchase was concluded, the

Minister and his family went down to Canterville

Chase. Mrs. Otis, who, as Miss Lucretia R. Tappan

(35) had been a celebrated New York belle, was now a

very handsome, middle-aged woman. Her eldest

son, christened Washington by his parents in a

moment of patriotism, was a fair-haired, rather

good-looking young man.

(40) Standing on the steps to receive them was old

Mrs. Umney, the housekeeper, whom Mrs. Otis, at

Lady Canterville's earnest request, had consented

to keep on in her former position. Following her

into the library, they found tea laid out for them,

(45) sat down and began to look round.

Suddenly Mrs. Otis caught sight of a dull red

stain on the floor just by the fireplace and said

to Mrs. Umney, “I am afraid something has been

spilt there.”

(50) “Yes, madam,” replied the old housekeeper in

a low voice, “blood has been spilt on that spot.”

“How horrid,” cried Mrs. Otis; “I don't at all

care for bloodstains in a sitting-room. It must be

removed at once.”

(55) The old woman answered in the same low,

mysterious voice, “It is the blood of Lady Eleanore

de Canterville, who was murdered on that spot by

her husband, Sir Simon de Canterville, in 1575.

His guilty spirit still haunts the Chase. The blood-

(60) stain has been much admired by tourists and

others, and cannot be removed.”

“That is all nonsense,” cried Washington;

“Pinkerton's Champion Stain Remover will

clean it up in no time,” and before the terrified

(65) housekeeper could interfere he was rapidly

scouring the floor. In a few moments no trace of

the blood-stain could be seen.

“I knew Pinkerton would do it,” he exclaimed

triumphantly, as he looked round at his admiring

(70) family. A terrible flash of lightning lit up the

somber room, a fearful peal of thunder made them

all start to their feet, and Mrs. Umney fainted.

“What a monstrous climate!” said the

American Minister calmly. “I guess the old

(75) country is so overpopulated that they have not

enough decent weather for everybody. I have

always been of opinion that emigration is the

only thing for England.”

“My dear Hiram,” cried Mrs. Otis, “what can

(80) we do with a woman who faints?”

“Charge it to her like breakages,” answered

the Minister; “she won't faint after that;” and in

a few moments Mrs. Umney certainly came to.

There was no doubt, however, that she was upset,

(85) and she sternly warned Mr. Otis to beware of

some trouble coming to the house.

“Many and many a night,” she said, “I have

not closed my eyes in sleep for the awful things

that are done here.” Mr. Otis, however, and his

(90) wife warmly assured the honest soul that they

were not afraid of ghosts, and, after invoking

the blessings of Providence on her new master

and mistress, and making arrangements for an

increase of salary, the old housekeeper tottered

(95) off to her own room.

Q. Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.

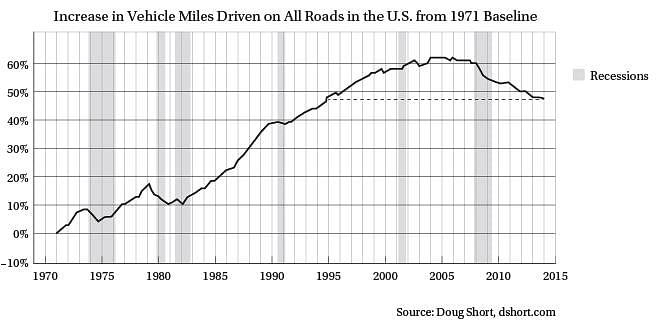

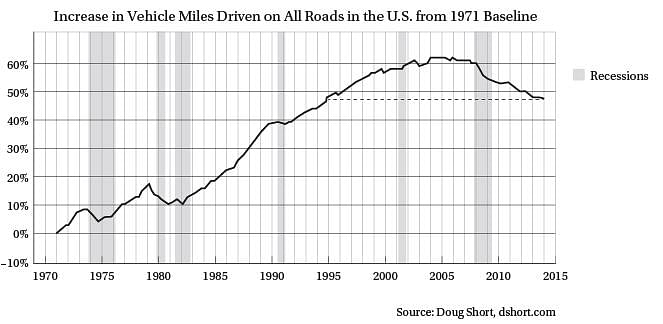

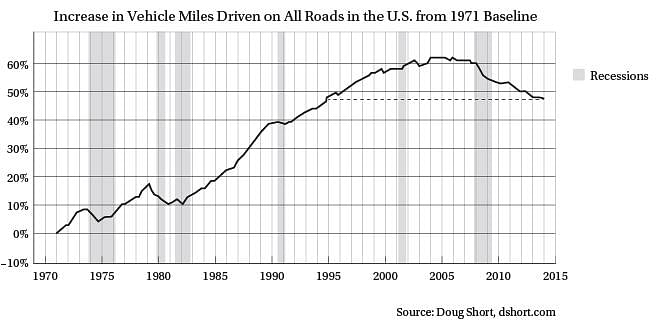

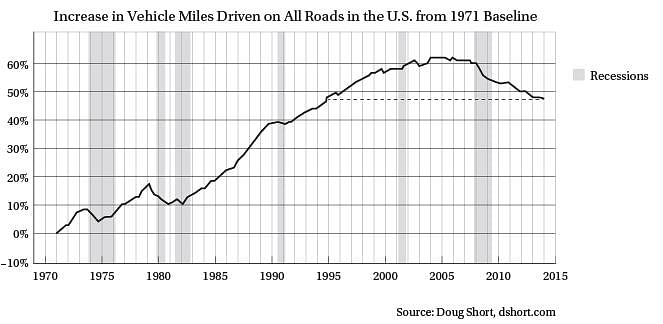

The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.

As traffic levels in the United States decline in

defiance of forecasts projecting major increases, a

number of commentators have claimed that we've

reached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in

(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comes

to an end. But while this has been celebrated by

many urbanists as undermining plans for more

roads, we have yet to face the implications peak

car has for public policy.

(10) For a long time, urbanists have embraced

Say's Law of Markets for roads: increasing the

supply of driving lanes only increases the number

of drivers to fill them, hence building more roads

to reduce congestion is pointless. But if we've

(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really can

build our way out of congestion after all.

Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallen

in recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked on

a per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.

(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994

levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travel

shows a marked reversal.

These data are complemented by a slew of

recent stories about the poor financial

(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in part

from traffic falling far below projections. On the

Indiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% in

eight years, in contrast with a forecasted increase

of 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.

(30) Many of the trends that drove high traffic

growth in the past have largely been played

out: household size declines, suburbanization,

the entry of women into the workforce, one

car per driver, etc. That's not to say these will

(35) necessarily reverse. But we've reached the point

of diminishing returns, particularly in terms of

how many more women will join the labor force.

This is potentially very good fiscal news,

especially given tight budgets. Clearly many

(40) freeway expansion projects that have been driven

by speculative demand should be revisited. From

top to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate their

forecasting models to better correspond to reality,

and then revisit highway plans accordingly.

(45) But we must also pay attention to the flip

side of peak car. Although speculative highway

expansion projects may be dubious, there may be

good reasons now to build projects designed to

alleviate already exiting congestion. Places like

(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, which

has great economic and social consequences,

not the least of which is the value of untold hours

lost sitting in traffic. Although some projects

there might indeed be boondoggles, maybe it's

(55) worth building some of the planned freeway

expansions there in light of peak car. In short,

in some cases—particularly where Say's Law no

longer seems to apply—peak car strengthens the

argument for building or expanding roads.

(60) On the other hand, many of the regional

development plans designed to promote compact

central city development and transit may be

predicated on an analysis that assumes large

future traffic increases in a “business as usual”

(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects of

regional planning are dependent on traffic

forecasts. That's not to say that such plans are

necessarily wrong, but clearly revised traffic

reality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just

(70) highway building ones.

Urbanists and policy makers of all stripes

need to think about the full implications of peak

car. At a minimum, the traditional “you can't

build your way out of congestion” rhetoric should

(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a more

nuanced approach that neither overestimates

demand, nor ignores the problems caused by

rapid growth in some regions and pockets of

congestion in others.

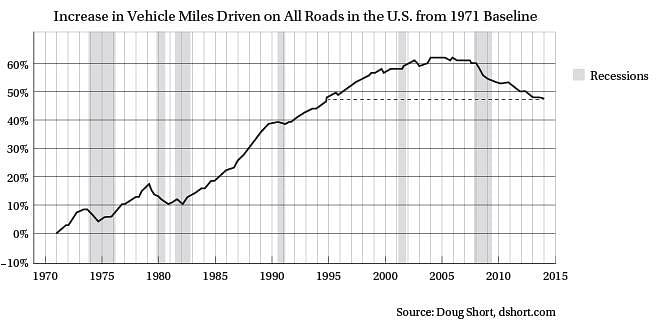

Q. The primary purpose of the first paragraph is to

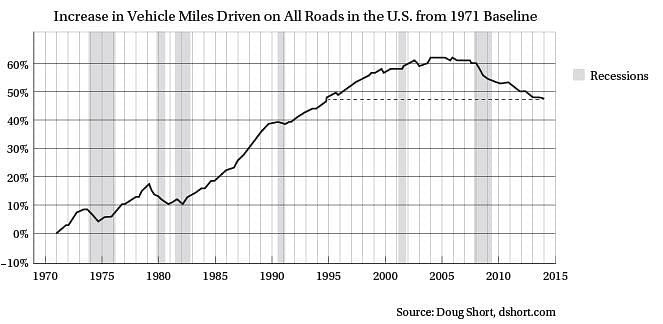

Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.

The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.

As traffic levels in the United States decline in

defiance of forecasts projecting major increases, a

number of commentators have claimed that we've

reached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in

(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comes

to an end. But while this has been celebrated by

many urbanists as undermining plans for more

roads, we have yet to face the implications peak

car has for public policy.

(10) For a long time, urbanists have embraced

Say's Law of Markets for roads: increasing the

supply of driving lanes only increases the number

of drivers to fill them, hence building more roads

to reduce congestion is pointless. But if we've

(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really can

build our way out of congestion after all.

Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallen

in recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked on

a per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.

(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994

levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travel

shows a marked reversal.

These data are complemented by a slew of

recent stories about the poor financial

(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in part

from traffic falling far below projections. On the

Indiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% in

eight years, in contrast with a forecasted increase

of 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.

(30) Many of the trends that drove high traffic

growth in the past have largely been played

out: household size declines, suburbanization,

the entry of women into the workforce, one

car per driver, etc. That's not to say these will

(35) necessarily reverse. But we've reached the point

of diminishing returns, particularly in terms of

how many more women will join the labor force.

This is potentially very good fiscal news,

especially given tight budgets. Clearly many

(40) freeway expansion projects that have been driven

by speculative demand should be revisited. From

top to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate their

forecasting models to better correspond to reality,

and then revisit highway plans accordingly.

(45) But we must also pay attention to the flip

side of peak car. Although speculative highway

expansion projects may be dubious, there may be

good reasons now to build projects designed to

alleviate already exiting congestion. Places like

(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, which

has great economic and social consequences,

not the least of which is the value of untold hours

lost sitting in traffic. Although some projects

there might indeed be boondoggles, maybe it's

(55) worth building some of the planned freeway

expansions there in light of peak car. In short,

in some cases—particularly where Say's Law no

longer seems to apply—peak car strengthens the

argument for building or expanding roads.

(60) On the other hand, many of the regional

development plans designed to promote compact

central city development and transit may be

predicated on an analysis that assumes large

future traffic increases in a “business as usual”

(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects of

regional planning are dependent on traffic

forecasts. That's not to say that such plans are

necessarily wrong, but clearly revised traffic

reality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just

(70) highway building ones.

Urbanists and policy makers of all stripes

need to think about the full implications of peak

car. At a minimum, the traditional “you can't

build your way out of congestion” rhetoric should

(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a more

nuanced approach that neither overestimates

demand, nor ignores the problems caused by

rapid growth in some regions and pockets of

congestion in others.

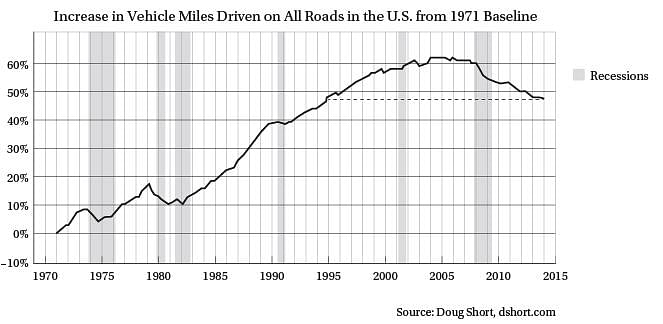

Q. As used in lines 14 and 16, “congestion” refers to a type of

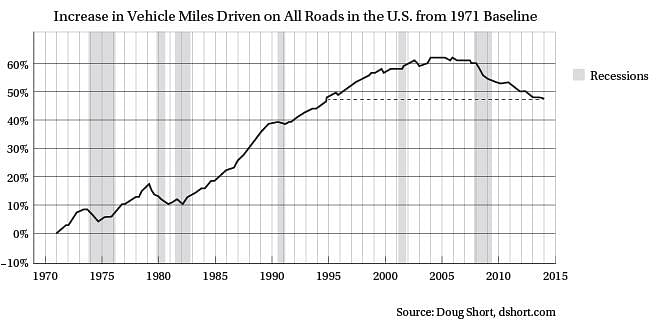

Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.

The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.

As traffic levels in the United States decline in

defiance of forecasts projecting major increases, a

number of commentators have claimed that we've

reached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in

(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comes

to an end. But while this has been celebrated by

many urbanists as undermining plans for more

roads, we have yet to face the implications peak

car has for public policy.

(10) For a long time, urbanists have embraced

Say's Law of Markets for roads: increasing the

supply of driving lanes only increases the number

of drivers to fill them, hence building more roads

to reduce congestion is pointless. But if we've

(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really can

build our way out of congestion after all.

Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallen

in recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked on

a per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.

(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994

levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travel

shows a marked reversal.

These data are complemented by a slew of

recent stories about the poor financial

(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in part

from traffic falling far below projections. On the

Indiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% in

eight years, in contrast with a forecasted increase

of 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.

(30) Many of the trends that drove high traffic

growth in the past have largely been played

out: household size declines, suburbanization,

the entry of women into the workforce, one

car per driver, etc. That's not to say these will

(35) necessarily reverse. But we've reached the point

of diminishing returns, particularly in terms of

how many more women will join the labor force.

This is potentially very good fiscal news,

especially given tight budgets. Clearly many

(40) freeway expansion projects that have been driven

by speculative demand should be revisited. From

top to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate their

forecasting models to better correspond to reality,

and then revisit highway plans accordingly.

(45) But we must also pay attention to the flip

side of peak car. Although speculative highway

expansion projects may be dubious, there may be

good reasons now to build projects designed to

alleviate already exiting congestion. Places like

(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, which

has great economic and social consequences,

not the least of which is the value of untold hours

lost sitting in traffic. Although some projects

there might indeed be boondoggles, maybe it's

(55) worth building some of the planned freeway

expansions there in light of peak car. In short,

in some cases—particularly where Say's Law no

longer seems to apply—peak car strengthens the

argument for building or expanding roads.

(60) On the other hand, many of the regional

development plans designed to promote compact

central city development and transit may be

predicated on an analysis that assumes large

future traffic increases in a “business as usual”

(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects of

regional planning are dependent on traffic

forecasts. That's not to say that such plans are

necessarily wrong, but clearly revised traffic

reality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just

(70) highway building ones.

Urbanists and policy makers of all stripes

need to think about the full implications of peak

car. At a minimum, the traditional “you can't

build your way out of congestion” rhetoric should

(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a more

nuanced approach that neither overestimates

demand, nor ignores the problems caused by

rapid growth in some regions and pockets of

congestion in others.

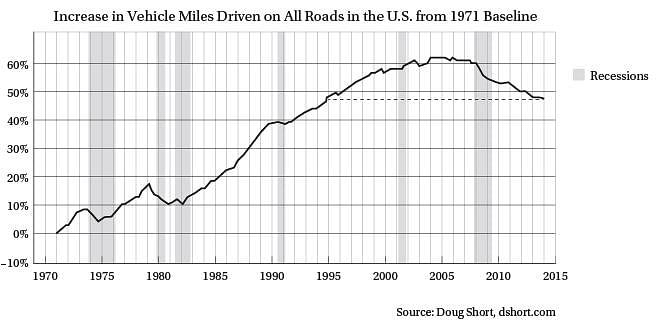

Q. Which situation best illustrates “Say’s Law of Markets” (lines 10–14)?

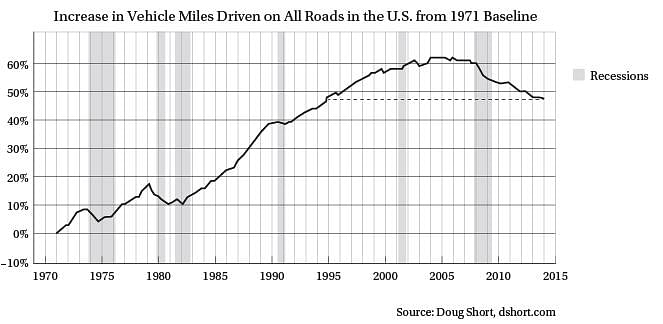

Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.

The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.

As traffic levels in the United States decline in

defiance of forecasts projecting major increases, a

number of commentators have claimed that we've

reached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in

(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comes

to an end. But while this has been celebrated by

many urbanists as undermining plans for more

roads, we have yet to face the implications peak

car has for public policy.

(10) For a long time, urbanists have embraced

Say's Law of Markets for roads: increasing the