Test: CLAT Mock Test - 15 - CLAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - Test: CLAT Mock Test - 15

Directions: Kindly read the passage carefully and answer the questions given beside.

We need the support of many people in life — parents, good friends, teachers and men of high moral calibre, elaborated R. Narayanan, in a discourse. Thiruvalluvar says that there can be nothing more auspicious for a man than to have a good wife. If he also has good children, then that is like being endowed with valuable ornaments. A good wife is a source of strength to her husband, especially when he faces troubles, financial or otherwise.

We must seek the company of virtuous people, for they are the ones who sustain the world through their upright conduct. The Tamil work Moothurai says that water which is used to irrigate crops, also flows to weeds, and keeps them alive. We get copious rains only because of the presence in this world of men with laudable traits. We also benefit because of this, though we may lack such sterling qualities. We may not have intrinsic merits, but association with great men will work to our benefit. We must find people who never deviate from the moral path, and befriend them. We should see them as our relatives. Associating with such men will prove to be our biggest strength, emphasises Thiruvalluvar.

Learned men can guide us to take the right path. It is important that a ruler of a country takes the advice of scholars. Thiruvalluvar says that a ruler who takes the advice of men of learning can never be defeated. An honest man, who has all desirable virtues, cannot tolerate even a small blemish in his character. Even if he makes a small mistake, he will repent for it, and be ashamed of what he has done. Life is full of hurdles, and it is like traversing a slippery path. Just as a man on a slippery path needs a stick to help him maintain his balance, so also do we need the help of great men to help us through life.

Q. Who are the people we require support from in life, according to R. Narayanan?

Directions: Kindly read the passage carefully and answer the questions given beside.

We need the support of many people in life — parents, good friends, teachers and men of high moral calibre, elaborated R. Narayanan, in a discourse. Thiruvalluvar says that there can be nothing more auspicious for a man than to have a good wife. If he also has good children, then that is like being endowed with valuable ornaments. A good wife is a source of strength to her husband, especially when he faces troubles, financial or otherwise.

We must seek the company of virtuous people, for they are the ones who sustain the world through their upright conduct. The Tamil work Moothurai says that water which is used to irrigate crops, also flows to weeds, and keeps them alive. We get copious rains only because of the presence in this world of men with laudable traits. We also benefit because of this, though we may lack such sterling qualities. We may not have intrinsic merits, but association with great men will work to our benefit. We must find people who never deviate from the moral path, and befriend them. We should see them as our relatives. Associating with such men will prove to be our biggest strength, emphasises Thiruvalluvar.

Learned men can guide us to take the right path. It is important that a ruler of a country takes the advice of scholars. Thiruvalluvar says that a ruler who takes the advice of men of learning can never be defeated. An honest man, who has all desirable virtues, cannot tolerate even a small blemish in his character. Even if he makes a small mistake, he will repent for it, and be ashamed of what he has done. Life is full of hurdles, and it is like traversing a slippery path. Just as a man on a slippery path needs a stick to help him maintain his balance, so also do we need the help of great men to help us through life.

Q. What does Thiruvalluvar think about the value of moral people in the world?

| 1 Crore+ students have signed up on EduRev. Have you? Download the App |

Directions: Kindly read the passage carefully and answer the questions given beside.

We need the support of many people in life — parents, good friends, teachers and men of high moral calibre, elaborated R. Narayanan, in a discourse. Thiruvalluvar says that there can be nothing more auspicious for a man than to have a good wife. If he also has good children, then that is like being endowed with valuable ornaments. A good wife is a source of strength to her husband, especially when he faces troubles, financial or otherwise.

We must seek the company of virtuous people, for they are the ones who sustain the world through their upright conduct. The Tamil work Moothurai says that water which is used to irrigate crops, also flows to weeds, and keeps them alive. We get copious rains only because of the presence in this world of men with laudable traits. We also benefit because of this, though we may lack such sterling qualities. We may not have intrinsic merits, but association with great men will work to our benefit. We must find people who never deviate from the moral path, and befriend them. We should see them as our relatives. Associating with such men will prove to be our biggest strength, emphasises Thiruvalluvar.

Learned men can guide us to take the right path. It is important that a ruler of a country takes the advice of scholars. Thiruvalluvar says that a ruler who takes the advice of men of learning can never be defeated. An honest man, who has all desirable virtues, cannot tolerate even a small blemish in his character. Even if he makes a small mistake, he will repent for it, and be ashamed of what he has done. Life is full of hurdles, and it is like traversing a slippery path. Just as a man on a slippery path needs a stick to help him maintain his balance, so also do we need the help of great men to help us through life.

Q. What does the passage's use of the term "sterling" mean?

Directions: Kindly read the passage carefully and answer the questions given beside.

We need the support of many people in life — parents, good friends, teachers and men of high moral calibre, elaborated R. Narayanan, in a discourse. Thiruvalluvar says that there can be nothing more auspicious for a man than to have a good wife. If he also has good children, then that is like being endowed with valuable ornaments. A good wife is a source of strength to her husband, especially when he faces troubles, financial or otherwise.

We must seek the company of virtuous people, for they are the ones who sustain the world through their upright conduct. The Tamil work Moothurai says that water which is used to irrigate crops, also flows to weeds, and keeps them alive. We get copious rains only because of the presence in this world of men with laudable traits. We also benefit because of this, though we may lack such sterling qualities. We may not have intrinsic merits, but association with great men will work to our benefit. We must find people who never deviate from the moral path, and befriend them. We should see them as our relatives. Associating with such men will prove to be our biggest strength, emphasises Thiruvalluvar.

Learned men can guide us to take the right path. It is important that a ruler of a country takes the advice of scholars. Thiruvalluvar says that a ruler who takes the advice of men of learning can never be defeated. An honest man, who has all desirable virtues, cannot tolerate even a small blemish in his character. Even if he makes a small mistake, he will repent for it, and be ashamed of what he has done. Life is full of hurdles, and it is like traversing a slippery path. Just as a man on a slippery path needs a stick to help him maintain his balance, so also do we need the help of great men to help us through life.

Q. According to Thiruvalluvar in the passage, why should we seek the company of virtuous people?

Directions: Kindly read the passage carefully and answer the questions given beside.

We need the support of many people in life — parents, good friends, teachers and men of high moral calibre, elaborated R. Narayanan, in a discourse. Thiruvalluvar says that there can be nothing more auspicious for a man than to have a good wife. If he also has good children, then that is like being endowed with valuable ornaments. A good wife is a source of strength to her husband, especially when he faces troubles, financial or otherwise.

We must seek the company of virtuous people, for they are the ones who sustain the world through their upright conduct. The Tamil work Moothurai says that water which is used to irrigate crops, also flows to weeds, and keeps them alive. We get copious rains only because of the presence in this world of men with laudable traits. We also benefit because of this, though we may lack such sterling qualities. We may not have intrinsic merits, but association with great men will work to our benefit. We must find people who never deviate from the moral path, and befriend them. We should see them as our relatives. Associating with such men will prove to be our biggest strength, emphasises Thiruvalluvar.

Learned men can guide us to take the right path. It is important that a ruler of a country takes the advice of scholars. Thiruvalluvar says that a ruler who takes the advice of men of learning can never be defeated. An honest man, who has all desirable virtues, cannot tolerate even a small blemish in his character. Even if he makes a small mistake, he will repent for it, and be ashamed of what he has done. Life is full of hurdles, and it is like traversing a slippery path. Just as a man on a slippery path needs a stick to help him maintain his balance, so also do we need the help of great men to help us through life.

Q. What role do learned men play in the passage?

Directions: Kindly read the passage carefully and answer the questions given beside.

Aunty Nusrat wasn’t someone I spent a lot of time with. I met her, or rather bumped into her, at family gatherings that she always attended punctually. She would greet me warmly with a hug and a sloppy kiss planted on my forehead. She would enquire about my family (even though she would see them standing right next to me) and my studies, and would heap blessings upon me, which included among many things becoming a big doctor and a mother to boys. She was mild and gentle towards everyone, and she was someone people usually said nice things about.

Over the years, this repeated exposure to Aunty Nusrat transformed and turned itself into a habit and then into an expectation. When I crossed into my early 20s, this expectation would announce itself at a family gathering in the form of a slight tug at the heart, which would then dissolve into a feeling of relief upon seeing her. It was as though my mind had a checklist for family gatherings that included Aunty Nusrat as one of the things I needed to cross off. The funny thing about these episodes was they lasted only a few seconds. They never entered my mind before or after the events. They existed only for as long as they took place.

One July afternoon, at a distant cousin’s engagement party, I felt the familiar tug at my heart. I looked around for Aunty Nusrat, but she was nowhere to be seen. I asked a few people, but no one had seen her. Later, closer to when the party was about to conclude, we learned that she had passed away. She had been getting ready to leave for the party when she had suddenly collapsed. She was taken to the hospital where she was declared dead. When we heard about her death, she had already been buried.

We went upstairs and after performing our ablutions, prayed side by side. Throughout the prayers, I felt that I was unable to concentrate. I was upset of course, but I couldn’t say that I was heartbroken or even deeply distressed. I couldn’t understand why I was feeling restless. I thought about Aunty Nusrat and how she had sort of just existed out there for as long as I could remember. I wasn’t missing her, maybe just missing the idea of her. She was like a painting that had stood in your home for years and now had suddenly disappeared, leaving behind just the impression on the wall, a painting that you mostly walked by most days but occasionally you would catch yourself stopping and gazing at its contents before walking off again.

Q. How would you describe the tone of the passage?

Directions: Kindly read the passage carefully and answer the questions given beside.

Aunty Nusrat wasn’t someone I spent a lot of time with. I met her, or rather bumped into her, at family gatherings that she always attended punctually. She would greet me warmly with a hug and a sloppy kiss planted on my forehead. She would enquire about my family (even though she would see them standing right next to me) and my studies, and would heap blessings upon me, which included among many things becoming a big doctor and a mother to boys. She was mild and gentle towards everyone, and she was someone people usually said nice things about.

Over the years, this repeated exposure to Aunty Nusrat transformed and turned itself into a habit and then into an expectation. When I crossed into my early 20s, this expectation would announce itself at a family gathering in the form of a slight tug at the heart, which would then dissolve into a feeling of relief upon seeing her. It was as though my mind had a checklist for family gatherings that included Aunty Nusrat as one of the things I needed to cross off. The funny thing about these episodes was they lasted only a few seconds. They never entered my mind before or after the events. They existed only for as long as they took place.

One July afternoon, at a distant cousin’s engagement party, I felt the familiar tug at my heart. I looked around for Aunty Nusrat, but she was nowhere to be seen. I asked a few people, but no one had seen her. Later, closer to when the party was about to conclude, we learned that she had passed away. She had been getting ready to leave for the party when she had suddenly collapsed. She was taken to the hospital where she was declared dead. When we heard about her death, she had already been buried.

We went upstairs and after performing our ablutions, prayed side by side. Throughout the prayers, I felt that I was unable to concentrate. I was upset of course, but I couldn’t say that I was heartbroken or even deeply distressed. I couldn’t understand why I was feeling restless. I thought about Aunty Nusrat and how she had sort of just existed out there for as long as I could remember. I wasn’t missing her, maybe just missing the idea of her. She was like a painting that had stood in your home for years and now had suddenly disappeared, leaving behind just the impression on the wall, a painting that you mostly walked by most days but occasionally you would catch yourself stopping and gazing at its contents before walking off again.

Q. How may Aunty Nusrat be deduced from the passage?

Directions: Kindly read the passage carefully and answer the questions given beside.

Aunty Nusrat wasn’t someone I spent a lot of time with. I met her, or rather bumped into her, at family gatherings that she always attended punctually. She would greet me warmly with a hug and a sloppy kiss planted on my forehead. She would enquire about my family (even though she would see them standing right next to me) and my studies, and would heap blessings upon me, which included among many things becoming a big doctor and a mother to boys. She was mild and gentle towards everyone, and she was someone people usually said nice things about.

Over the years, this repeated exposure to Aunty Nusrat transformed and turned itself into a habit and then into an expectation. When I crossed into my early 20s, this expectation would announce itself at a family gathering in the form of a slight tug at the heart, which would then dissolve into a feeling of relief upon seeing her. It was as though my mind had a checklist for family gatherings that included Aunty Nusrat as one of the things I needed to cross off. The funny thing about these episodes was they lasted only a few seconds. They never entered my mind before or after the events. They existed only for as long as they took place.

One July afternoon, at a distant cousin’s engagement party, I felt the familiar tug at my heart. I looked around for Aunty Nusrat, but she was nowhere to be seen. I asked a few people, but no one had seen her. Later, closer to when the party was about to conclude, we learned that she had passed away. She had been getting ready to leave for the party when she had suddenly collapsed. She was taken to the hospital where she was declared dead. When we heard about her death, she had already been buried.

We went upstairs and after performing our ablutions, prayed side by side. Throughout the prayers, I felt that I was unable to concentrate. I was upset of course, but I couldn’t say that I was heartbroken or even deeply distressed. I couldn’t understand why I was feeling restless. I thought about Aunty Nusrat and how she had sort of just existed out there for as long as I could remember. I wasn’t missing her, maybe just missing the idea of her. She was like a painting that had stood in your home for years and now had suddenly disappeared, leaving behind just the impression on the wall, a painting that you mostly walked by most days but occasionally you would catch yourself stopping and gazing at its contents before walking off again.

Q. How did Aunty Nusrat and the narrator typically communicate?

Directions: Kindly read the passage carefully and answer the questions given beside.

Aunty Nusrat wasn’t someone I spent a lot of time with. I met her, or rather bumped into her, at family gatherings that she always attended punctually. She would greet me warmly with a hug and a sloppy kiss planted on my forehead. She would enquire about my family (even though she would see them standing right next to me) and my studies, and would heap blessings upon me, which included among many things becoming a big doctor and a mother to boys. She was mild and gentle towards everyone, and she was someone people usually said nice things about.

Over the years, this repeated exposure to Aunty Nusrat transformed and turned itself into a habit and then into an expectation. When I crossed into my early 20s, this expectation would announce itself at a family gathering in the form of a slight tug at the heart, which would then dissolve into a feeling of relief upon seeing her. It was as though my mind had a checklist for family gatherings that included Aunty Nusrat as one of the things I needed to cross off. The funny thing about these episodes was they lasted only a few seconds. They never entered my mind before or after the events. They existed only for as long as they took place.

One July afternoon, at a distant cousin’s engagement party, I felt the familiar tug at my heart. I looked around for Aunty Nusrat, but she was nowhere to be seen. I asked a few people, but no one had seen her. Later, closer to when the party was about to conclude, we learned that she had passed away. She had been getting ready to leave for the party when she had suddenly collapsed. She was taken to the hospital where she was declared dead. When we heard about her death, she had already been buried.

We went upstairs and after performing our ablutions, prayed side by side. Throughout the prayers, I felt that I was unable to concentrate. I was upset of course, but I couldn’t say that I was heartbroken or even deeply distressed. I couldn’t understand why I was feeling restless. I thought about Aunty Nusrat and how she had sort of just existed out there for as long as I could remember. I wasn’t missing her, maybe just missing the idea of her. She was like a painting that had stood in your home for years and now had suddenly disappeared, leaving behind just the impression on the wall, a painting that you mostly walked by most days but occasionally you would catch yourself stopping and gazing at its contents before walking off again.

Q. What is the author's initial impression of Aunty Nusrat?

Directions: Kindly read the passage carefully and answer the questions given beside.

Aunty Nusrat wasn’t someone I spent a lot of time with. I met her, or rather bumped into her, at family gatherings that she always attended punctually. She would greet me warmly with a hug and a sloppy kiss planted on my forehead. She would enquire about my family (even though she would see them standing right next to me) and my studies, and would heap blessings upon me, which included among many things becoming a big doctor and a mother to boys. She was mild and gentle towards everyone, and she was someone people usually said nice things about.

Over the years, this repeated exposure to Aunty Nusrat transformed and turned itself into a habit and then into an expectation. When I crossed into my early 20s, this expectation would announce itself at a family gathering in the form of a slight tug at the heart, which would then dissolve into a feeling of relief upon seeing her. It was as though my mind had a checklist for family gatherings that included Aunty Nusrat as one of the things I needed to cross off. The funny thing about these episodes was they lasted only a few seconds. They never entered my mind before or after the events. They existed only for as long as they took place.

One July afternoon, at a distant cousin’s engagement party, I felt the familiar tug at my heart. I looked around for Aunty Nusrat, but she was nowhere to be seen. I asked a few people, but no one had seen her. Later, closer to when the party was about to conclude, we learned that she had passed away. She had been getting ready to leave for the party when she had suddenly collapsed. She was taken to the hospital where she was declared dead. When we heard about her death, she had already been buried.

We went upstairs and after performing our ablutions, prayed side by side. Throughout the prayers, I felt that I was unable to concentrate. I was upset of course, but I couldn’t say that I was heartbroken or even deeply distressed. I couldn’t understand why I was feeling restless. I thought about Aunty Nusrat and how she had sort of just existed out there for as long as I could remember. I wasn’t missing her, maybe just missing the idea of her. She was like a painting that had stood in your home for years and now had suddenly disappeared, leaving behind just the impression on the wall, a painting that you mostly walked by most days but occasionally you would catch yourself stopping and gazing at its contents before walking off again.

Q. How did the author's feelings toward Aunty Nusrat change as they grew older?

Directions: Kindly read the passage carefully and answer the questions given beside.

A colossal statue of the Buddha, surrounded by cells for monks who conduct daily prayer services. That might be how we imagine a Buddhist monastery today. But for many who lived in present-day Sri Lanka a thousand years ago, that was what a hospital looked like.

Religious leaders throughout history have sought to care for their followers in various ways, and Buddhists were no exception. In fact, excavation projects in Sri Lanka have come up with the ruins of medieval monastic hospitals of a scale that hasn’t yet been seen anywhere in South Asia—even in India, with its long-standing Ayurvedic tradition. With new archaeological data, historians can now reconstruct these medieval healthcare administrations, endowments, and facilities.

In the late 19th century, Indologist Wilhelm Geiger came across some rather strange-looking stone troughs in Sri Lanka. They had cavities roughly the shape of human beings and finely-carved exteriors decorated with mouldings and pilasters. He noted that they were being used to serve food to pilgrims, since their original purpose had been long forgotten. In Stone Sarcophagi and Ancient Hospitals in Sri Lanka, physician Heinz Mueller-Dietz mentions this story with a persuasive explanation: These were not originally feeding troughs but medical tubs. Filled with “plant liniments, milk, ghee, oils, and vinegar”, Mueller-Dietz suggests that they could have been used “for the treatment of rheumatism, haemorrhoids, fever, and snake bites”.

Since then, excavations across Sri Lanka have turned up more of these medical tubs, leading to at least four major monastic hospitals being identified across the island. Possibly the most impressive was at Mihintale, near the ancient Lankan capital of Anuradhapura, the primary seat of the island’s kings until the late 10th century CE. It is also the oldest-surviving structure dedicated primarily to healthcare. Archaeologist Leelananda Prematilleke published a study of the site in The Archaeology of Buddhist Monastic Hospitals, part of the volume The Archaeology of Buddhism: Recent Discoveries from South Asia.

Situated close to Anuradhapura, this complex consisted of two courtyards, the first of which had 25 cells and larger rooms arranged around a central shrine with a colossal Buddha statue. This opened to another courtyard with four to five adjoining rooms. Persian blue glass flasks were discovered in these rooms, along with mortars and pestles for grinding herbs and a pool with heating facilities.

Q. Which of the following statements, as stated in the passage, is untrue?

Directions: Kindly read the passage carefully and answer the questions given beside.

A colossal statue of the Buddha, surrounded by cells for monks who conduct daily prayer services. That might be how we imagine a Buddhist monastery today. But for many who lived in present-day Sri Lanka a thousand years ago, that was what a hospital looked like.

Religious leaders throughout history have sought to care for their followers in various ways, and Buddhists were no exception. In fact, excavation projects in Sri Lanka have come up with the ruins of medieval monastic hospitals of a scale that hasn’t yet been seen anywhere in South Asia—even in India, with its long-standing Ayurvedic tradition. With new archaeological data, historians can now reconstruct these medieval healthcare administrations, endowments, and facilities.

In the late 19th century, Indologist Wilhelm Geiger came across some rather strange-looking stone troughs in Sri Lanka. They had cavities roughly the shape of human beings and finely-carved exteriors decorated with mouldings and pilasters. He noted that they were being used to serve food to pilgrims, since their original purpose had been long forgotten. In Stone Sarcophagi and Ancient Hospitals in Sri Lanka, physician Heinz Mueller-Dietz mentions this story with a persuasive explanation: These were not originally feeding troughs but medical tubs. Filled with “plant liniments, milk, ghee, oils, and vinegar”, Mueller-Dietz suggests that they could have been used “for the treatment of rheumatism, haemorrhoids, fever, and snake bites”.

Since then, excavations across Sri Lanka have turned up more of these medical tubs, leading to at least four major monastic hospitals being identified across the island. Possibly the most impressive was at Mihintale, near the ancient Lankan capital of Anuradhapura, the primary seat of the island’s kings until the late 10th century CE. It is also the oldest-surviving structure dedicated primarily to healthcare. Archaeologist Leelananda Prematilleke published a study of the site in The Archaeology of Buddhist Monastic Hospitals, part of the volume The Archaeology of Buddhism: Recent Discoveries from South Asia.

Situated close to Anuradhapura, this complex consisted of two courtyards, the first of which had 25 cells and larger rooms arranged around a central shrine with a colossal Buddha statue. This opened to another courtyard with four to five adjoining rooms. Persian blue glass flasks were discovered in these rooms, along with mortars and pestles for grinding herbs and a pool with heating facilities.

Q. What inference can be drawn regarding the monastic hospitals in Sri Lanka?

Directions: Kindly read the passage carefully and answer the questions given beside.

A colossal statue of the Buddha, surrounded by cells for monks who conduct daily prayer services. That might be how we imagine a Buddhist monastery today. But for many who lived in present-day Sri Lanka a thousand years ago, that was what a hospital looked like.

Religious leaders throughout history have sought to care for their followers in various ways, and Buddhists were no exception. In fact, excavation projects in Sri Lanka have come up with the ruins of medieval monastic hospitals of a scale that hasn’t yet been seen anywhere in South Asia—even in India, with its long-standing Ayurvedic tradition. With new archaeological data, historians can now reconstruct these medieval healthcare administrations, endowments, and facilities.

In the late 19th century, Indologist Wilhelm Geiger came across some rather strange-looking stone troughs in Sri Lanka. They had cavities roughly the shape of human beings and finely-carved exteriors decorated with mouldings and pilasters. He noted that they were being used to serve food to pilgrims, since their original purpose had been long forgotten. In Stone Sarcophagi and Ancient Hospitals in Sri Lanka, physician Heinz Mueller-Dietz mentions this story with a persuasive explanation: These were not originally feeding troughs but medical tubs. Filled with “plant liniments, milk, ghee, oils, and vinegar”, Mueller-Dietz suggests that they could have been used “for the treatment of rheumatism, haemorrhoids, fever, and snake bites”.

Since then, excavations across Sri Lanka have turned up more of these medical tubs, leading to at least four major monastic hospitals being identified across the island. Possibly the most impressive was at Mihintale, near the ancient Lankan capital of Anuradhapura, the primary seat of the island’s kings until the late 10th century CE. It is also the oldest-surviving structure dedicated primarily to healthcare. Archaeologist Leelananda Prematilleke published a study of the site in The Archaeology of Buddhist Monastic Hospitals, part of the volume The Archaeology of Buddhism: Recent Discoveries from South Asia.

Situated close to Anuradhapura, this complex consisted of two courtyards, the first of which had 25 cells and larger rooms arranged around a central shrine with a colossal Buddha statue. This opened to another courtyard with four to five adjoining rooms. Persian blue glass flasks were discovered in these rooms, along with mortars and pestles for grinding herbs and a pool with heating facilities.

Q. Where did this passage come from?

Directions: Kindly read the passage carefully and answer the questions given beside.

A colossal statue of the Buddha, surrounded by cells for monks who conduct daily prayer services. That might be how we imagine a Buddhist monastery today. But for many who lived in present-day Sri Lanka a thousand years ago, that was what a hospital looked like.

Religious leaders throughout history have sought to care for their followers in various ways, and Buddhists were no exception. In fact, excavation projects in Sri Lanka have come up with the ruins of medieval monastic hospitals of a scale that hasn’t yet been seen anywhere in South Asia—even in India, with its long-standing Ayurvedic tradition. With new archaeological data, historians can now reconstruct these medieval healthcare administrations, endowments, and facilities.

In the late 19th century, Indologist Wilhelm Geiger came across some rather strange-looking stone troughs in Sri Lanka. They had cavities roughly the shape of human beings and finely-carved exteriors decorated with mouldings and pilasters. He noted that they were being used to serve food to pilgrims, since their original purpose had been long forgotten. In Stone Sarcophagi and Ancient Hospitals in Sri Lanka, physician Heinz Mueller-Dietz mentions this story with a persuasive explanation: These were not originally feeding troughs but medical tubs. Filled with “plant liniments, milk, ghee, oils, and vinegar”, Mueller-Dietz suggests that they could have been used “for the treatment of rheumatism, haemorrhoids, fever, and snake bites”.

Since then, excavations across Sri Lanka have turned up more of these medical tubs, leading to at least four major monastic hospitals being identified across the island. Possibly the most impressive was at Mihintale, near the ancient Lankan capital of Anuradhapura, the primary seat of the island’s kings until the late 10th century CE. It is also the oldest-surviving structure dedicated primarily to healthcare. Archaeologist Leelananda Prematilleke published a study of the site in The Archaeology of Buddhist Monastic Hospitals, part of the volume The Archaeology of Buddhism: Recent Discoveries from South Asia.

Situated close to Anuradhapura, this complex consisted of two courtyards, the first of which had 25 cells and larger rooms arranged around a central shrine with a colossal Buddha statue. This opened to another courtyard with four to five adjoining rooms. Persian blue glass flasks were discovered in these rooms, along with mortars and pestles for grinding herbs and a pool with heating facilities.

Q. What was the original purpose of the stone troughs mentioned in the passage?

Directions: Kindly read the passage carefully and answer the questions given beside.

A colossal statue of the Buddha, surrounded by cells for monks who conduct daily prayer services. That might be how we imagine a Buddhist monastery today. But for many who lived in present-day Sri Lanka a thousand years ago, that was what a hospital looked like.

Religious leaders throughout history have sought to care for their followers in various ways, and Buddhists were no exception. In fact, excavation projects in Sri Lanka have come up with the ruins of medieval monastic hospitals of a scale that hasn’t yet been seen anywhere in South Asia—even in India, with its long-standing Ayurvedic tradition. With new archaeological data, historians can now reconstruct these medieval healthcare administrations, endowments, and facilities.

In the late 19th century, Indologist Wilhelm Geiger came across some rather strange-looking stone troughs in Sri Lanka. They had cavities roughly the shape of human beings and finely-carved exteriors decorated with mouldings and pilasters. He noted that they were being used to serve food to pilgrims, since their original purpose had been long forgotten. In Stone Sarcophagi and Ancient Hospitals in Sri Lanka, physician Heinz Mueller-Dietz mentions this story with a persuasive explanation: These were not originally feeding troughs but medical tubs. Filled with “plant liniments, milk, ghee, oils, and vinegar”, Mueller-Dietz suggests that they could have been used “for the treatment of rheumatism, haemorrhoids, fever, and snake bites”.

Since then, excavations across Sri Lanka have turned up more of these medical tubs, leading to at least four major monastic hospitals being identified across the island. Possibly the most impressive was at Mihintale, near the ancient Lankan capital of Anuradhapura, the primary seat of the island’s kings until the late 10th century CE. It is also the oldest-surviving structure dedicated primarily to healthcare. Archaeologist Leelananda Prematilleke published a study of the site in The Archaeology of Buddhist Monastic Hospitals, part of the volume The Archaeology of Buddhism: Recent Discoveries from South Asia.

Situated close to Anuradhapura, this complex consisted of two courtyards, the first of which had 25 cells and larger rooms arranged around a central shrine with a colossal Buddha statue. This opened to another courtyard with four to five adjoining rooms. Persian blue glass flasks were discovered in these rooms, along with mortars and pestles for grinding herbs and a pool with heating facilities.

Q. Where was the most impressive monastic hospital located, as described in the passage?

Directions: Read the following passage and answer the question.

Here's my latest report on things grown-ups say but don't actually mean.

So, our school's Annual Day finally happened last week and I couldn't be happier. This year, I decided that I wanted to try something different, so I opted for media and editing. What's that, you ask? Who cares, I thought. As long as I didn't have to dress up as a sunflower and wave my arms about while lip-synching to the song by Post Malone, I didn't really care.

But to be honest, I thought media and editing would be cool. That I'd learn how to create special effects which I could then use on my YouTube channel. That it would launch my movie career. HA! Can you tell that that is not what happened?

A tad off?

First, the Sir who taught us editing was not some cool guy with amazing stories about how he worked on The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings. He worked in an IT company and spent most of his time 'writing code'. And not cool spy code but Python. Bleh.

Well, after he taught us a few of the basics, we were divided into groups and told to start working on backdrops for some of the scenes in the production. When we went to him with ideas and images and clips he kept waving us away and saying "No! No! Show me the final thing. And remember, it's not about being perfect! It's about learning."

DOUBLE HA!

So, after spending weeks and weeks finding stuff and putting it together, Sir finally takes a look and tells us that it's terrible! That we can't have work like this up on the stage. That we should have come to him sooner. That it was all a terrible disaster. Are you confused by his reaction? I sure was.

I don't know if you've ever tried to correct a grown up, but let me save you the trouble and tell you not to bother. They hate being reminded that they said one thing and are doing the exact opposite. When we tried to tell Sir that we had come to him with ideas and that he said perfection didn't matter — he kicked us off the team! YUP! You read that right. He said that if we'd spent more time working and less time arguing and answering back, then our work would have looked better.

So, I present to you 'Things grownups say but don't actually mean #103: The results don't matter, the learning does'. You can also apply this to chemistry lab explosions and getting your report card signed by your parents.

I had to spend the rest of Annual Day practice as an understudy. To a lamp post.

Q. What did the author choose to study for the Annual Day event?

Directions: Read the following passage and answer the question.

Here's my latest report on things grown-ups say but don't actually mean.

So, our school's Annual Day finally happened last week and I couldn't be happier. This year, I decided that I wanted to try something different, so I opted for media and editing. What's that, you ask? Who cares, I thought. As long as I didn't have to dress up as a sunflower and wave my arms about while lip-synching to the song by Post Malone, I didn't really care.

But to be honest, I thought media and editing would be cool. That I'd learn how to create special effects which I could then use on my YouTube channel. That it would launch my movie career. HA! Can you tell that that is not what happened?

A tad off?

First, the Sir who taught us editing was not some cool guy with amazing stories about how he worked on The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings. He worked in an IT company and spent most of his time 'writing code'. And not cool spy code but Python. Bleh.

Well, after he taught us a few of the basics, we were divided into groups and told to start working on backdrops for some of the scenes in the production. When we went to him with ideas and images and clips he kept waving us away and saying "No! No! Show me the final thing. And remember, it's not about being perfect! It's about learning."

DOUBLE HA!

So, after spending weeks and weeks finding stuff and putting it together, Sir finally takes a look and tells us that it's terrible! That we can't have work like this up on the stage. That we should have come to him sooner. That it was all a terrible disaster. Are you confused by his reaction? I sure was.

I don't know if you've ever tried to correct a grown up, but let me save you the trouble and tell you not to bother. They hate being reminded that they said one thing and are doing the exact opposite. When we tried to tell Sir that we had come to him with ideas and that he said perfection didn't matter — he kicked us off the team! YUP! You read that right. He said that if we'd spent more time working and less time arguing and answering back, then our work would have looked better.

So, I present to you 'Things grownups say but don't actually mean #103: The results don't matter, the learning does'. You can also apply this to chemistry lab explosions and getting your report card signed by your parents.

I had to spend the rest of Annual Day practice as an understudy. To a lamp post.

Q. How did the author and their group react when their work on the backdrops was criticized by the teacher?

Directions: Read the following passage and answer the question.

Here's my latest report on things grown-ups say but don't actually mean.

So, our school's Annual Day finally happened last week and I couldn't be happier. This year, I decided that I wanted to try something different, so I opted for media and editing. What's that, you ask? Who cares, I thought. As long as I didn't have to dress up as a sunflower and wave my arms about while lip-synching to the song by Post Malone, I didn't really care.

But to be honest, I thought media and editing would be cool. That I'd learn how to create special effects which I could then use on my YouTube channel. That it would launch my movie career. HA! Can you tell that that is not what happened?

A tad off?

First, the Sir who taught us editing was not some cool guy with amazing stories about how he worked on The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings. He worked in an IT company and spent most of his time 'writing code'. And not cool spy code but Python. Bleh.

Well, after he taught us a few of the basics, we were divided into groups and told to start working on backdrops for some of the scenes in the production. When we went to him with ideas and images and clips he kept waving us away and saying "No! No! Show me the final thing. And remember, it's not about being perfect! It's about learning."

DOUBLE HA!

So, after spending weeks and weeks finding stuff and putting it together, Sir finally takes a look and tells us that it's terrible! That we can't have work like this up on the stage. That we should have come to him sooner. That it was all a terrible disaster. Are you confused by his reaction? I sure was.

I don't know if you've ever tried to correct a grown up, but let me save you the trouble and tell you not to bother. They hate being reminded that they said one thing and are doing the exact opposite. When we tried to tell Sir that we had come to him with ideas and that he said perfection didn't matter — he kicked us off the team! YUP! You read that right. He said that if we'd spent more time working and less time arguing and answering back, then our work would have looked better.

So, I present to you 'Things grownups say but don't actually mean #103: The results don't matter, the learning does'. You can also apply this to chemistry lab explosions and getting your report card signed by your parents.

I had to spend the rest of Annual Day practice as an understudy. To a lamp post.

Q. How did the Sir respond when the author and other students approached him with suggestions for the assignment?

Directions: Read the following passage and answer the question.

Here's my latest report on things grown-ups say but don't actually mean.

So, our school's Annual Day finally happened last week and I couldn't be happier. This year, I decided that I wanted to try something different, so I opted for media and editing. What's that, you ask? Who cares, I thought. As long as I didn't have to dress up as a sunflower and wave my arms about while lip-synching to the song by Post Malone, I didn't really care.

But to be honest, I thought media and editing would be cool. That I'd learn how to create special effects which I could then use on my YouTube channel. That it would launch my movie career. HA! Can you tell that that is not what happened?

A tad off?

First, the Sir who taught us editing was not some cool guy with amazing stories about how he worked on The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings. He worked in an IT company and spent most of his time 'writing code'. And not cool spy code but Python. Bleh.

Well, after he taught us a few of the basics, we were divided into groups and told to start working on backdrops for some of the scenes in the production. When we went to him with ideas and images and clips he kept waving us away and saying "No! No! Show me the final thing. And remember, it's not about being perfect! It's about learning."

DOUBLE HA!

So, after spending weeks and weeks finding stuff and putting it together, Sir finally takes a look and tells us that it's terrible! That we can't have work like this up on the stage. That we should have come to him sooner. That it was all a terrible disaster. Are you confused by his reaction? I sure was.

I don't know if you've ever tried to correct a grown up, but let me save you the trouble and tell you not to bother. They hate being reminded that they said one thing and are doing the exact opposite. When we tried to tell Sir that we had come to him with ideas and that he said perfection didn't matter — he kicked us off the team! YUP! You read that right. He said that if we'd spent more time working and less time arguing and answering back, then our work would have looked better.

So, I present to you 'Things grownups say but don't actually mean #103: The results don't matter, the learning does'. You can also apply this to chemistry lab explosions and getting your report card signed by your parents.

I had to spend the rest of Annual Day practice as an understudy. To a lamp post.

Q. What does the passage's usage of the word "opted" mean?

Directions: Read the following passage and answer the question.

Here's my latest report on things grown-ups say but don't actually mean.

So, our school's Annual Day finally happened last week and I couldn't be happier. This year, I decided that I wanted to try something different, so I opted for media and editing. What's that, you ask? Who cares, I thought. As long as I didn't have to dress up as a sunflower and wave my arms about while lip-synching to the song by Post Malone, I didn't really care.

But to be honest, I thought media and editing would be cool. That I'd learn how to create special effects which I could then use on my YouTube channel. That it would launch my movie career. HA! Can you tell that that is not what happened?

A tad off?

First, the Sir who taught us editing was not some cool guy with amazing stories about how he worked on The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings. He worked in an IT company and spent most of his time 'writing code'. And not cool spy code but Python. Bleh.

Well, after he taught us a few of the basics, we were divided into groups and told to start working on backdrops for some of the scenes in the production. When we went to him with ideas and images and clips he kept waving us away and saying "No! No! Show me the final thing. And remember, it's not about being perfect! It's about learning."

DOUBLE HA!

So, after spending weeks and weeks finding stuff and putting it together, Sir finally takes a look and tells us that it's terrible! That we can't have work like this up on the stage. That we should have come to him sooner. That it was all a terrible disaster. Are you confused by his reaction? I sure was.

I don't know if you've ever tried to correct a grown up, but let me save you the trouble and tell you not to bother. They hate being reminded that they said one thing and are doing the exact opposite. When we tried to tell Sir that we had come to him with ideas and that he said perfection didn't matter — he kicked us off the team! YUP! You read that right. He said that if we'd spent more time working and less time arguing and answering back, then our work would have looked better.

So, I present to you 'Things grownups say but don't actually mean #103: The results don't matter, the learning does'. You can also apply this to chemistry lab explosions and getting your report card signed by your parents.

I had to spend the rest of Annual Day practice as an understudy. To a lamp post.

Q. Which of the following conclusions drawn from the passage cannot be trusted?

Directions: Read the following passage and answer the question.

One summer, many years ago, while I was living in the garden city of Pune, I lay in bed, unwell. Lying in bed, I watched a large neem tree teeming with activity. Birds like orioles, flycatchers, and magpie robins were frequent visitors to the tree. Another cute resident on the neem tree was the palm squirrel; common in peninsular India. As I lay in bed, I enjoyed watching these creatures go about their daily tasks. Their activities on the tree made me get well quicker!

Then one day, I saw to my dismay that the tree was being chopped down to widen the road in the neighbouring society. I had watched the squirrel build its nest all summer, and it was with sadness I watched as the tree was slowly chopped down. I wondered what happened to the squirrel nesting in the tree.

The loss of the squirrel's nest made me sad. After much thought, I decided to do something about this. The loss of the tree led me to find out that in India trees, even the ones planted by us in our homes, need permission before they are chopped.

Over the next few years, I got involved in a programme called Pune Tree Watch, where citizens engaged with the Garden Department, to reduce tree felling in the rapidly developing city of Pune. We looked to balance development with the green needs of the city. We sought solutions like tree transplantation, alternate routes for roads or different designs for buildings, sewage and pipelines to save trees. In two to three years, we were able to save many trees, and create awareness about the laws relating to tree felling among citizens.

In 2008, I shifted to Dehradun, where I continued my work to save urban biodiversity. We worked with citizens and institutions _ the municipal and forest departments _ to save green cover in Dehradun. Over the last few years, we have successfully transplanted some trees, and saved many of them from being felled, too.

My ultimate reward in this line of work came when a tree in the middle of Dehradun city was being cut down. I watched as a squirrel ran down the tree that the municipality was chopping, and run up the one we had saved. It had lost a home, but found a new one. All the work I had done in the last decade seemed worthwhile.

It took a squirrel and a tree to move me from being aware and feeling sad, to action. All of us need to act to save nature.

So, what will be your "squirrel" moment?

[Extracted with edits and revisions from 'Who moved my tree?', The Hindu]

Q. Which of the following situations might be compared to the one in which the author chose to fight for the protection of trees in his area?

Directions: Read the following passage and answer the question.

One summer, many years ago, while I was living in the garden city of Pune, I lay in bed, unwell. Lying in bed, I watched a large neem tree teeming with activity. Birds like orioles, flycatchers, and magpie robins were frequent visitors to the tree. Another cute resident on the neem tree was the palm squirrel; common in peninsular India. As I lay in bed, I enjoyed watching these creatures go about their daily tasks. Their activities on the tree made me get well quicker!

Then one day, I saw to my dismay that the tree was being chopped down to widen the road in the neighbouring society. I had watched the squirrel build its nest all summer, and it was with sadness I watched as the tree was slowly chopped down. I wondered what happened to the squirrel nesting in the tree.

The loss of the squirrel's nest made me sad. After much thought, I decided to do something about this. The loss of the tree led me to find out that in India trees, even the ones planted by us in our homes, need permission before they are chopped.

Over the next few years, I got involved in a programme called Pune Tree Watch, where citizens engaged with the Garden Department, to reduce tree felling in the rapidly developing city of Pune. We looked to balance development with the green needs of the city. We sought solutions like tree transplantation, alternate routes for roads or different designs for buildings, sewage and pipelines to save trees. In two to three years, we were able to save many trees, and create awareness about the laws relating to tree felling among citizens.

In 2008, I shifted to Dehradun, where I continued my work to save urban biodiversity. We worked with citizens and institutions _ the municipal and forest departments _ to save green cover in Dehradun. Over the last few years, we have successfully transplanted some trees, and saved many of them from being felled, too.

My ultimate reward in this line of work came when a tree in the middle of Dehradun city was being cut down. I watched as a squirrel ran down the tree that the municipality was chopping, and run up the one we had saved. It had lost a home, but found a new one. All the work I had done in the last decade seemed worthwhile.

It took a squirrel and a tree to move me from being aware and feeling sad, to action. All of us need to act to save nature.

So, what will be your "squirrel" moment?

[Extracted with edits and revisions from 'Who moved my tree?', The Hindu]

Q. What does the passage's usage of the term "dismay" mean?

Directions: Read the following passage and answer the question.

One summer, many years ago, while I was living in the garden city of Pune, I lay in bed, unwell. Lying in bed, I watched a large neem tree teeming with activity. Birds like orioles, flycatchers, and magpie robins were frequent visitors to the tree. Another cute resident on the neem tree was the palm squirrel; common in peninsular India. As I lay in bed, I enjoyed watching these creatures go about their daily tasks. Their activities on the tree made me get well quicker!

Then one day, I saw to my dismay that the tree was being chopped down to widen the road in the neighbouring society. I had watched the squirrel build its nest all summer, and it was with sadness I watched as the tree was slowly chopped down. I wondered what happened to the squirrel nesting in the tree.

The loss of the squirrel's nest made me sad. After much thought, I decided to do something about this. The loss of the tree led me to find out that in India trees, even the ones planted by us in our homes, need permission before they are chopped.

Over the next few years, I got involved in a programme called Pune Tree Watch, where citizens engaged with the Garden Department, to reduce tree felling in the rapidly developing city of Pune. We looked to balance development with the green needs of the city. We sought solutions like tree transplantation, alternate routes for roads or different designs for buildings, sewage and pipelines to save trees. In two to three years, we were able to save many trees, and create awareness about the laws relating to tree felling among citizens.

In 2008, I shifted to Dehradun, where I continued my work to save urban biodiversity. We worked with citizens and institutions _ the municipal and forest departments _ to save green cover in Dehradun. Over the last few years, we have successfully transplanted some trees, and saved many of them from being felled, too.

My ultimate reward in this line of work came when a tree in the middle of Dehradun city was being cut down. I watched as a squirrel ran down the tree that the municipality was chopping, and run up the one we had saved. It had lost a home, but found a new one. All the work I had done in the last decade seemed worthwhile.

It took a squirrel and a tree to move me from being aware and feeling sad, to action. All of us need to act to save nature.

So, what will be your "squirrel" moment?

[Extracted with edits and revisions from 'Who moved my tree?', The Hindu]

Q. Which of the following, as per the passage, prompted the author to believe that he ought to take action over tree cutting?

Directions: Read the following passage and answer the question.

One summer, many years ago, while I was living in the garden city of Pune, I lay in bed, unwell. Lying in bed, I watched a large neem tree teeming with activity. Birds like orioles, flycatchers, and magpie robins were frequent visitors to the tree. Another cute resident on the neem tree was the palm squirrel; common in peninsular India. As I lay in bed, I enjoyed watching these creatures go about their daily tasks. Their activities on the tree made me get well quicker!

Then one day, I saw to my dismay that the tree was being chopped down to widen the road in the neighbouring society. I had watched the squirrel build its nest all summer, and it was with sadness I watched as the tree was slowly chopped down. I wondered what happened to the squirrel nesting in the tree.

The loss of the squirrel's nest made me sad. After much thought, I decided to do something about this. The loss of the tree led me to find out that in India trees, even the ones planted by us in our homes, need permission before they are chopped.

Over the next few years, I got involved in a programme called Pune Tree Watch, where citizens engaged with the Garden Department, to reduce tree felling in the rapidly developing city of Pune. We looked to balance development with the green needs of the city. We sought solutions like tree transplantation, alternate routes for roads or different designs for buildings, sewage and pipelines to save trees. In two to three years, we were able to save many trees, and create awareness about the laws relating to tree felling among citizens.

In 2008, I shifted to Dehradun, where I continued my work to save urban biodiversity. We worked with citizens and institutions _ the municipal and forest departments _ to save green cover in Dehradun. Over the last few years, we have successfully transplanted some trees, and saved many of them from being felled, too.

My ultimate reward in this line of work came when a tree in the middle of Dehradun city was being cut down. I watched as a squirrel ran down the tree that the municipality was chopping, and run up the one we had saved. It had lost a home, but found a new one. All the work I had done in the last decade seemed worthwhile.

It took a squirrel and a tree to move me from being aware and feeling sad, to action. All of us need to act to save nature.

So, what will be your "squirrel" moment?

[Extracted with edits and revisions from 'Who moved my tree?', The Hindu]

Q. What motivated the narrator to get involved in the Pune Tree Watch program?

Directions: Read the following passage and answer the question.

One summer, many years ago, while I was living in the garden city of Pune, I lay in bed, unwell. Lying in bed, I watched a large neem tree teeming with activity. Birds like orioles, flycatchers, and magpie robins were frequent visitors to the tree. Another cute resident on the neem tree was the palm squirrel; common in peninsular India. As I lay in bed, I enjoyed watching these creatures go about their daily tasks. Their activities on the tree made me get well quicker!

Then one day, I saw to my dismay that the tree was being chopped down to widen the road in the neighbouring society. I had watched the squirrel build its nest all summer, and it was with sadness I watched as the tree was slowly chopped down. I wondered what happened to the squirrel nesting in the tree.

The loss of the squirrel's nest made me sad. After much thought, I decided to do something about this. The loss of the tree led me to find out that in India trees, even the ones planted by us in our homes, need permission before they are chopped.

Over the next few years, I got involved in a programme called Pune Tree Watch, where citizens engaged with the Garden Department, to reduce tree felling in the rapidly developing city of Pune. We looked to balance development with the green needs of the city. We sought solutions like tree transplantation, alternate routes for roads or different designs for buildings, sewage and pipelines to save trees. In two to three years, we were able to save many trees, and create awareness about the laws relating to tree felling among citizens.

In 2008, I shifted to Dehradun, where I continued my work to save urban biodiversity. We worked with citizens and institutions _ the municipal and forest departments _ to save green cover in Dehradun. Over the last few years, we have successfully transplanted some trees, and saved many of them from being felled, too.

My ultimate reward in this line of work came when a tree in the middle of Dehradun city was being cut down. I watched as a squirrel ran down the tree that the municipality was chopping, and run up the one we had saved. It had lost a home, but found a new one. All the work I had done in the last decade seemed worthwhile.

It took a squirrel and a tree to move me from being aware and feeling sad, to action. All of us need to act to save nature.

So, what will be your "squirrel" moment?

[Extracted with edits and revisions from 'Who moved my tree?', The Hindu]

Q. What was the ultimate reward for the narrator in their efforts to save trees and urban biodiversity?

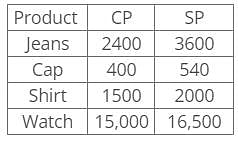

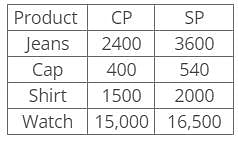

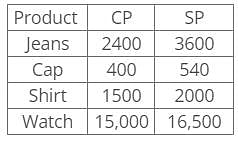

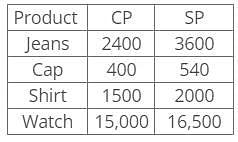

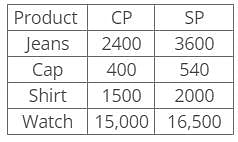

Directions: Study the following information carefully and answer the questions given beside.

A customer purchased four items, a Jeans, a Cap, a Shirt and a Watch, from a lifestyle store. The store owner sold all the items at a certain profit after allowing some discount to the customer.

Jeans cost six times as much as the cap and 16% as much as the watch while the cost of the shirt is 90% less than that of the watch.

The store owner sold the jeans, cap, shirt and watch at a profit of 50%, 35%, 33.33% and 10% respectively.

The customer spent a total of Rs. 22640 on all four products combined.

Q. If the jeans and the shirt are marked 60% and 80% above their cost prices, what is the difference between their marked prices?

Directions: Study the following information carefully and answer the questions given beside.

A customer purchased four items, a Jeans, a Cap, a Shirt and a Watch, from a lifestyle store. The store owner sold all the items at a certain profit after allowing some discount to the customer.

Jeans cost six times as much as the cap and 16% as much as the watch while the cost of the shirt is 90% less than that of the watch.

The store owner sold the jeans, cap, shirt and watch at a profit of 50%, 35%, 33.33% and 10% respectively.

The customer spent a total of Rs. 22640 on all four products combined.

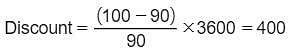

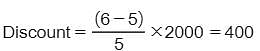

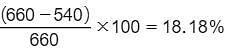

Q. If the Jeans and the Shirt are sold at a discount of 10% and 16.67%, respectively, what is the ratio of the discount on the Jeans to that on the Shirt?

Directions: Study the following information carefully and answer the questions given beside.

A customer purchased four items, a Jeans, a Cap, a Shirt and a Watch, from a lifestyle store. The store owner sold all the items at a certain profit after allowing some discount to the customer.

Jeans cost six times as much as the cap and 16% as much as the watch while the cost of the shirt is 90% less than that of the watch.

The store owner sold the jeans, cap, shirt and watch at a profit of 50%, 35%, 33.33% and 10% respectively.

The customer spent a total of Rs. 22640 on all four products combined.

Q. What is the selling price of the watch?

Directions: Study the following information carefully and answer the questions given beside.

A customer purchased four items, a Jeans, a Cap, a Shirt and a Watch, from a lifestyle store. The store owner sold all the items at a certain profit after allowing some discount to the customer.

Jeans cost six times as much as the cap and 16% as much as the watch while the cost of the shirt is 90% less than that of the watch.

The store owner sold the jeans, cap, shirt and watch at a profit of 50%, 35%, 33.33% and 10% respectively.

The customer spent a total of Rs. 22640 on all four products combined.

Q. How much profit did the store owner earn on the shirt?

Directions: Study the following information carefully and answer the questions given beside.

A customer purchased four items, a Jeans, a Cap, a Shirt and a Watch, from a lifestyle store. The store owner sold all the items at a certain profit after allowing some discount to the customer.

Jeans cost six times as much as the cap and 16% as much as the watch while the cost of the shirt is 90% less than that of the watch.

The store owner sold the jeans, cap, shirt and watch at a profit of 50%, 35%, 33.33% and 10% respectively.

The customer spent a total of Rs. 22640 on all four products combined.

Q. If the cap is marked 65% above its cost price, at what percentage discount the cap is sold?