SAT Exam > SAT Questions > Question based on the following passage and s...

Start Learning for Free

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Bryan Walsh, "Whole Food Blues: Why Organic Agriculture May Not Be So Sustainable." ©2012 by Time Inc.

When it comes to energy, everyone loves

efficiency. Cutting energy waste is one of those goals

that both sides of the political divide can agree on,

even if they sometimes diverge on how best to get

(5) there. Energy efficiency allows us to get more out of

our given resources, which is good for the economy

and (mostly) good for the environment as well. In

an increasingly hot and crowded world, the only

sustainable way to live is to get more out of less.

(10) Every environmentalist would agree.

But change the conversation to food, and

suddenly efficiency doesn’t look so good.

Conventional industrial agriculture has become

incredibly efficient on a simple land to food basis.

(15) Thanks to fertilizers, mechanization and irrigation,

each American farmer feeds over 155 people

worldwide. Conventional farming gets more and

more crop per square foot of cultivated land—

over 170 bushels of corn per acre in Iowa, for

(20) example—which can mean less territory needs to

be converted from wilderness to farmland.

And since a third of the planet is already used for

agriculture—destroying forests and other wild

habitats along the way—anything that could help us

(25) produce more food on less land would seem to be

good for the environment.

Of course, that’s not how most environmentalists

regard their arugula [a leafy green]. They have

embraced organic food as better for the planet—and

(30) healthier and tastier, too—than the stuff produced by

agricultural corporations. Environmentalists disdain

the enormous amounts of energy needed and waste

created by conventional farming, while organic

practices—forgoing artificial fertilizers and chemical

(35) pesticides—are considered far more sustainable.

Sales of organic food rose 7.7% in 2010, up to $26.7

billion—and people are making those purchases for

their consciences as much as their taste buds.

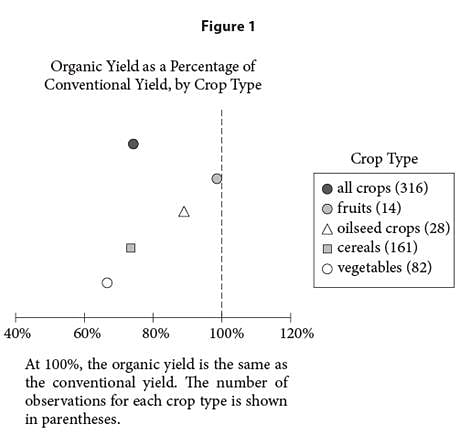

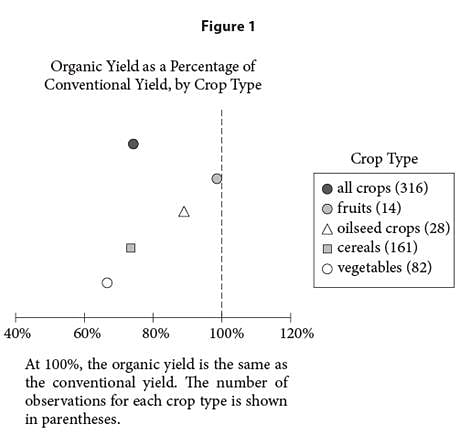

Yet a new meta-analysis in Nature does the math

(40) and comes to a hard conclusion: organic farming

yields 25% fewer crops on average than conventional

agriculture. More land is therefore needed to

produce fewer crops—and that means organic

farming may not be as good for the planet as

(45) we think.

In the Nature analysis, scientists from McGill

University in Montreal and the University of

Minnesota performed an analysis of 66 studies

comparing conventional and organic methods across

(50) 34 different crop species, from fruits to grains to

legumes. They found that organic farming delivered

a lower yield for every crop type, though the disparity

varied widely. For rain-watered legume crops like

beans or perennial crops like fruit trees, organic

(55) trailed conventional agriculture by just 5%. Yet for

major cereal crops like corn or wheat, as well as most

vegetables—all of which provide the bulk of the

world’s calories—conventional agriculture

outperformed organics by more than 25%.

(60) The main difference is nitrogen, the chemical key

to plant growth. Conventional agriculture makes use

of 171 million metric tons of synthetic fertilizer each

year, and all that nitrogen enables much faster plant

growth than the slower release of nitrogen from the

(65) compost or cover crops used in organic farming.

When we talk about a Green Revolution, we really

mean a nitrogen revolution—along with a lot of

water.

But not all the nitrogen used in conventional

(70) fertilizer ends up in crops—much of it ends up

running off the soil and into the oceans, creating vast

polluted dead zones. We’re already putting more

nitrogen into the soil than the planet can stand over

the long term. And conventional agriculture also

(75) depends heavily on chemical pesticides, which can

have unintended side effects.

What that means is that while conventional

agriculture is more efficient—sometimes much more

efficient—than organic farming, there are trade-offs

(80) with each. So an ideal global agriculture system, in

the views of the study’s authors, may borrow the best

from both systems, as Jonathan Foley of the

University of Minnesota explained:

The bottom line? Today’s organic farming

(85) practices are probably best deployed in fruit and

vegetable farms, where growing nutrition (not

just bulk calories) is the primary goal. But for

delivering sheer calories, especially in our staple

crops of wheat, rice, maize, soybeans and so on,

(90) conventional farms have the advantage right now.

Looking forward, I think we will need to deploy

different kinds of practices (especially new,

mixed approaches that take the best of organic

(95) and conventional farming systems) where they

are best suited—geographically, economically,

socially, etc.

This passage is adapted from Bryan Walsh, "Whole Food Blues: Why Organic Agriculture May Not Be So Sustainable." ©2012 by Time Inc.

When it comes to energy, everyone loves

efficiency. Cutting energy waste is one of those goals

that both sides of the political divide can agree on,

even if they sometimes diverge on how best to get

(5) there. Energy efficiency allows us to get more out of

our given resources, which is good for the economy

and (mostly) good for the environment as well. In

an increasingly hot and crowded world, the only

sustainable way to live is to get more out of less.

(10) Every environmentalist would agree.

But change the conversation to food, and

suddenly efficiency doesn’t look so good.

Conventional industrial agriculture has become

incredibly efficient on a simple land to food basis.

(15) Thanks to fertilizers, mechanization and irrigation,

each American farmer feeds over 155 people

worldwide. Conventional farming gets more and

more crop per square foot of cultivated land—

over 170 bushels of corn per acre in Iowa, for

(20) example—which can mean less territory needs to

be converted from wilderness to farmland.

And since a third of the planet is already used for

agriculture—destroying forests and other wild

habitats along the way—anything that could help us

(25) produce more food on less land would seem to be

good for the environment.

Of course, that’s not how most environmentalists

regard their arugula [a leafy green]. They have

embraced organic food as better for the planet—and

(30) healthier and tastier, too—than the stuff produced by

agricultural corporations. Environmentalists disdain

the enormous amounts of energy needed and waste

created by conventional farming, while organic

practices—forgoing artificial fertilizers and chemical

(35) pesticides—are considered far more sustainable.

Sales of organic food rose 7.7% in 2010, up to $26.7

billion—and people are making those purchases for

their consciences as much as their taste buds.

Yet a new meta-analysis in Nature does the math

(40) and comes to a hard conclusion: organic farming

yields 25% fewer crops on average than conventional

agriculture. More land is therefore needed to

produce fewer crops—and that means organic

farming may not be as good for the planet as

(45) we think.

In the Nature analysis, scientists from McGill

University in Montreal and the University of

Minnesota performed an analysis of 66 studies

comparing conventional and organic methods across

(50) 34 different crop species, from fruits to grains to

legumes. They found that organic farming delivered

a lower yield for every crop type, though the disparity

varied widely. For rain-watered legume crops like

beans or perennial crops like fruit trees, organic

(55) trailed conventional agriculture by just 5%. Yet for

major cereal crops like corn or wheat, as well as most

vegetables—all of which provide the bulk of the

world’s calories—conventional agriculture

outperformed organics by more than 25%.

(60) The main difference is nitrogen, the chemical key

to plant growth. Conventional agriculture makes use

of 171 million metric tons of synthetic fertilizer each

year, and all that nitrogen enables much faster plant

growth than the slower release of nitrogen from the

(65) compost or cover crops used in organic farming.

When we talk about a Green Revolution, we really

mean a nitrogen revolution—along with a lot of

water.

But not all the nitrogen used in conventional

(70) fertilizer ends up in crops—much of it ends up

running off the soil and into the oceans, creating vast

polluted dead zones. We’re already putting more

nitrogen into the soil than the planet can stand over

the long term. And conventional agriculture also

(75) depends heavily on chemical pesticides, which can

have unintended side effects.

What that means is that while conventional

agriculture is more efficient—sometimes much more

efficient—than organic farming, there are trade-offs

(80) with each. So an ideal global agriculture system, in

the views of the study’s authors, may borrow the best

from both systems, as Jonathan Foley of the

University of Minnesota explained:

The bottom line? Today’s organic farming

(85) practices are probably best deployed in fruit and

vegetable farms, where growing nutrition (not

just bulk calories) is the primary goal. But for

delivering sheer calories, especially in our staple

crops of wheat, rice, maize, soybeans and so on,

(90) conventional farms have the advantage right now.

Looking forward, I think we will need to deploy

different kinds of practices (especially new,

mixed approaches that take the best of organic

(95) and conventional farming systems) where they

are best suited—geographically, economically,

socially, etc.

Q. In line 88, “sheer” most nearly means

- a)transparent.

- b)abrupt.

- c)steep.

- d)pure.

Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer?

Verified Answer

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Thi...

Choice D is the best answer. The passage states that conventional agriculture can be superior to organic farming in terms of producing "sheer calories" (line 88). In this context, "sheer" most nearly means pure; the passage is referring to the pure number of calories delivered by foods.

Choices A, B, and C are incorrect because in the context of discussing the calories foods can provide, "sheer" suggests the pure number of calories. Also, it does not make sense to say that calories can be seen through (choice A), are somehow sudden or happen unexpectedly (choice B), or are at a very sharp angle (choice C).

Choices A, B, and C are incorrect because in the context of discussing the calories foods can provide, "sheer" suggests the pure number of calories. Also, it does not make sense to say that calories can be seen through (choice A), are somehow sudden or happen unexpectedly (choice B), or are at a very sharp angle (choice C).

Most Upvoted Answer

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Thi...

Choice D is the best answer. The passage states that conventional agriculture can be superior to organic farming in terms of producing "sheer calories" (line 88). In this context, "sheer" most nearly means pure; the passage is referring to the pure number of calories delivered by foods.

Choices A, B, and C are incorrect because in the context of discussing the calories foods can provide, "sheer" suggests the pure number of calories. Also, it does not make sense to say that calories can be seen through (choice A), are somehow sudden or happen unexpectedly (choice B), or are at a very sharp angle (choice C).

Choices A, B, and C are incorrect because in the context of discussing the calories foods can provide, "sheer" suggests the pure number of calories. Also, it does not make sense to say that calories can be seen through (choice A), are somehow sudden or happen unexpectedly (choice B), or are at a very sharp angle (choice C).

|

Explore Courses for SAT exam

|

|

Similar SAT Doubts

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Bryan Walsh, "Whole Food Blues: Why Organic Agriculture May Not Be So Sustainable." ©2012 by Time Inc.When it comes to energy, everyone lovesefficiency. Cutting energy waste is one of those goalsthat both sides of the political divide can agree on,even if they sometimes diverge on how best to get(5) there. Energy efficiency allows us to get more out ofour given resources, which is good for the economyand (mostly) good for the environment as well. Inan increasingly hot and crowded world, the onlysustainable way to live is to get more out of less.(10) Every environmentalist would agree.But change the conversation to food, andsuddenly efficiency doesn’t look so good.Conventional industrial agriculture has becomeincredibly efficient on a simple land to food basis.(15) Thanks to fertilizers, mechanization and irrigation,each American farmer feeds over 155 peopleworldwide. Conventional farming gets more andmore crop per square foot of cultivated land—over 170 bushels of corn per acre in Iowa, for(20) example—which can mean less territory needs tobe converted from wilderness to farmland.And since a third of the planet is already used foragriculture—destroying forests and other wildhabitats along the way—anything that could help us(25) produce more food on less land would seem to begood for the environment.Of course, that’s not how most environmentalistsregard their arugula [a leafy green]. They haveembraced organic food as better for the planet—and(30) healthier and tastier, too—than the stuff produced byagricultural corporations. Environmentalists disdainthe enormous amounts of energy needed and wastecreated by conventional farming, while organicpractices—forgoing artificial fertilizers and chemical(35) pesticides—are considered far more sustainable.Sales of organic food rose 7.7% in 2010, up to $26.7billion—and people are making those purchases fortheir consciences as much as their taste buds.Yet a new meta-analysis in Nature does the math(40) and comes to a hard conclusion: organic farmingyields 25% fewer crops on average than conventionalagriculture. More land is therefore needed toproduce fewer crops—and that means organicfarming may not be as good for the planet as(45) we think.In the Nature analysis, scientists from McGillUniversity in Montreal and the University ofMinnesota performed an analysis of 66 studiescomparing conventional and organic methods across(50) 34 different crop species, from fruits to grains tolegumes. They found that organic farming delivereda lower yield for every crop type, though the disparityvaried widely. For rain-watered legume crops likebeans or perennial crops like fruit trees, organic(55) trailed conventional agriculture by just 5%. Yet formajor cereal crops like corn or wheat, as well as mostvegetables—all of which provide the bulk of theworld’s calories—conventional agricultureoutperformed organics by more than 25%.(60) The main difference is nitrogen, the chemical keyto plant growth. Conventional agriculture makes useof 171 million metric tons of synthetic fertilizer eachyear, and all that nitrogen enables much faster plantgrowth than the slower release of nitrogen from the(65) compost or cover crops used in organic farming.When we talk about a Green Revolution, we reallymean a nitrogen revolution—along with a lot ofwater.But not all the nitrogen used in conventional(70) fertilizer ends up in crops—much of it ends uprunning off the soil and into the oceans, creating vastpolluted dead zones. We’re already putting morenitrogen into the soil than the planet can stand overthe long term. And conventional agriculture also(75) depends heavily on chemical pesticides, which canhave unintended side effects.What that means is that while conventionalagriculture is more efficient—sometimes much moreefficient—than organic farming, there are trade-offs(80) with each. So an ideal global agriculture system, inthe views of the study’s authors, may borrow the bestfrom both systems, as Jonathan Foley of theUniversity of Minnesota explained:The bottom line? Today’s organic farming(85) practices are probably best deployed in fruit andvegetable farms, where growing nutrition (notjust bulk calories) is the primary goal. But fordelivering sheer calories, especially in our staplecrops of wheat, rice, maize, soybeans and so on,(90) conventional farms have the advantage right now.Looking forward, I think we will need to deploydifferent kinds of practices (especially new,mixed approaches that take the best of organic(95) and conventional farming systems) where theyare best suited—geographically, economically,socially, etc.Q.In line 88, “sheer” most nearly meansa)transparent.b)abrupt.c)steep.d)pure.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer?

Question Description

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Bryan Walsh, "Whole Food Blues: Why Organic Agriculture May Not Be So Sustainable." ©2012 by Time Inc.When it comes to energy, everyone lovesefficiency. Cutting energy waste is one of those goalsthat both sides of the political divide can agree on,even if they sometimes diverge on how best to get(5) there. Energy efficiency allows us to get more out ofour given resources, which is good for the economyand (mostly) good for the environment as well. Inan increasingly hot and crowded world, the onlysustainable way to live is to get more out of less.(10) Every environmentalist would agree.But change the conversation to food, andsuddenly efficiency doesn’t look so good.Conventional industrial agriculture has becomeincredibly efficient on a simple land to food basis.(15) Thanks to fertilizers, mechanization and irrigation,each American farmer feeds over 155 peopleworldwide. Conventional farming gets more andmore crop per square foot of cultivated land—over 170 bushels of corn per acre in Iowa, for(20) example—which can mean less territory needs tobe converted from wilderness to farmland.And since a third of the planet is already used foragriculture—destroying forests and other wildhabitats along the way—anything that could help us(25) produce more food on less land would seem to begood for the environment.Of course, that’s not how most environmentalistsregard their arugula [a leafy green]. They haveembraced organic food as better for the planet—and(30) healthier and tastier, too—than the stuff produced byagricultural corporations. Environmentalists disdainthe enormous amounts of energy needed and wastecreated by conventional farming, while organicpractices—forgoing artificial fertilizers and chemical(35) pesticides—are considered far more sustainable.Sales of organic food rose 7.7% in 2010, up to $26.7billion—and people are making those purchases fortheir consciences as much as their taste buds.Yet a new meta-analysis in Nature does the math(40) and comes to a hard conclusion: organic farmingyields 25% fewer crops on average than conventionalagriculture. More land is therefore needed toproduce fewer crops—and that means organicfarming may not be as good for the planet as(45) we think.In the Nature analysis, scientists from McGillUniversity in Montreal and the University ofMinnesota performed an analysis of 66 studiescomparing conventional and organic methods across(50) 34 different crop species, from fruits to grains tolegumes. They found that organic farming delivereda lower yield for every crop type, though the disparityvaried widely. For rain-watered legume crops likebeans or perennial crops like fruit trees, organic(55) trailed conventional agriculture by just 5%. Yet formajor cereal crops like corn or wheat, as well as mostvegetables—all of which provide the bulk of theworld’s calories—conventional agricultureoutperformed organics by more than 25%.(60) The main difference is nitrogen, the chemical keyto plant growth. Conventional agriculture makes useof 171 million metric tons of synthetic fertilizer eachyear, and all that nitrogen enables much faster plantgrowth than the slower release of nitrogen from the(65) compost or cover crops used in organic farming.When we talk about a Green Revolution, we reallymean a nitrogen revolution—along with a lot ofwater.But not all the nitrogen used in conventional(70) fertilizer ends up in crops—much of it ends uprunning off the soil and into the oceans, creating vastpolluted dead zones. We’re already putting morenitrogen into the soil than the planet can stand overthe long term. And conventional agriculture also(75) depends heavily on chemical pesticides, which canhave unintended side effects.What that means is that while conventionalagriculture is more efficient—sometimes much moreefficient—than organic farming, there are trade-offs(80) with each. So an ideal global agriculture system, inthe views of the study’s authors, may borrow the bestfrom both systems, as Jonathan Foley of theUniversity of Minnesota explained:The bottom line? Today’s organic farming(85) practices are probably best deployed in fruit andvegetable farms, where growing nutrition (notjust bulk calories) is the primary goal. But fordelivering sheer calories, especially in our staplecrops of wheat, rice, maize, soybeans and so on,(90) conventional farms have the advantage right now.Looking forward, I think we will need to deploydifferent kinds of practices (especially new,mixed approaches that take the best of organic(95) and conventional farming systems) where theyare best suited—geographically, economically,socially, etc.Q.In line 88, “sheer” most nearly meansa)transparent.b)abrupt.c)steep.d)pure.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? for SAT 2025 is part of SAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the SAT exam syllabus. Information about Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Bryan Walsh, "Whole Food Blues: Why Organic Agriculture May Not Be So Sustainable." ©2012 by Time Inc.When it comes to energy, everyone lovesefficiency. Cutting energy waste is one of those goalsthat both sides of the political divide can agree on,even if they sometimes diverge on how best to get(5) there. Energy efficiency allows us to get more out ofour given resources, which is good for the economyand (mostly) good for the environment as well. Inan increasingly hot and crowded world, the onlysustainable way to live is to get more out of less.(10) Every environmentalist would agree.But change the conversation to food, andsuddenly efficiency doesn’t look so good.Conventional industrial agriculture has becomeincredibly efficient on a simple land to food basis.(15) Thanks to fertilizers, mechanization and irrigation,each American farmer feeds over 155 peopleworldwide. Conventional farming gets more andmore crop per square foot of cultivated land—over 170 bushels of corn per acre in Iowa, for(20) example—which can mean less territory needs tobe converted from wilderness to farmland.And since a third of the planet is already used foragriculture—destroying forests and other wildhabitats along the way—anything that could help us(25) produce more food on less land would seem to begood for the environment.Of course, that’s not how most environmentalistsregard their arugula [a leafy green]. They haveembraced organic food as better for the planet—and(30) healthier and tastier, too—than the stuff produced byagricultural corporations. Environmentalists disdainthe enormous amounts of energy needed and wastecreated by conventional farming, while organicpractices—forgoing artificial fertilizers and chemical(35) pesticides—are considered far more sustainable.Sales of organic food rose 7.7% in 2010, up to $26.7billion—and people are making those purchases fortheir consciences as much as their taste buds.Yet a new meta-analysis in Nature does the math(40) and comes to a hard conclusion: organic farmingyields 25% fewer crops on average than conventionalagriculture. More land is therefore needed toproduce fewer crops—and that means organicfarming may not be as good for the planet as(45) we think.In the Nature analysis, scientists from McGillUniversity in Montreal and the University ofMinnesota performed an analysis of 66 studiescomparing conventional and organic methods across(50) 34 different crop species, from fruits to grains tolegumes. They found that organic farming delivereda lower yield for every crop type, though the disparityvaried widely. For rain-watered legume crops likebeans or perennial crops like fruit trees, organic(55) trailed conventional agriculture by just 5%. Yet formajor cereal crops like corn or wheat, as well as mostvegetables—all of which provide the bulk of theworld’s calories—conventional agricultureoutperformed organics by more than 25%.(60) The main difference is nitrogen, the chemical keyto plant growth. Conventional agriculture makes useof 171 million metric tons of synthetic fertilizer eachyear, and all that nitrogen enables much faster plantgrowth than the slower release of nitrogen from the(65) compost or cover crops used in organic farming.When we talk about a Green Revolution, we reallymean a nitrogen revolution—along with a lot ofwater.But not all the nitrogen used in conventional(70) fertilizer ends up in crops—much of it ends uprunning off the soil and into the oceans, creating vastpolluted dead zones. We’re already putting morenitrogen into the soil than the planet can stand overthe long term. And conventional agriculture also(75) depends heavily on chemical pesticides, which canhave unintended side effects.What that means is that while conventionalagriculture is more efficient—sometimes much moreefficient—than organic farming, there are trade-offs(80) with each. So an ideal global agriculture system, inthe views of the study’s authors, may borrow the bestfrom both systems, as Jonathan Foley of theUniversity of Minnesota explained:The bottom line? Today’s organic farming(85) practices are probably best deployed in fruit andvegetable farms, where growing nutrition (notjust bulk calories) is the primary goal. But fordelivering sheer calories, especially in our staplecrops of wheat, rice, maize, soybeans and so on,(90) conventional farms have the advantage right now.Looking forward, I think we will need to deploydifferent kinds of practices (especially new,mixed approaches that take the best of organic(95) and conventional farming systems) where theyare best suited—geographically, economically,socially, etc.Q.In line 88, “sheer” most nearly meansa)transparent.b)abrupt.c)steep.d)pure.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for SAT 2025 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Bryan Walsh, "Whole Food Blues: Why Organic Agriculture May Not Be So Sustainable." ©2012 by Time Inc.When it comes to energy, everyone lovesefficiency. Cutting energy waste is one of those goalsthat both sides of the political divide can agree on,even if they sometimes diverge on how best to get(5) there. Energy efficiency allows us to get more out ofour given resources, which is good for the economyand (mostly) good for the environment as well. Inan increasingly hot and crowded world, the onlysustainable way to live is to get more out of less.(10) Every environmentalist would agree.But change the conversation to food, andsuddenly efficiency doesn’t look so good.Conventional industrial agriculture has becomeincredibly efficient on a simple land to food basis.(15) Thanks to fertilizers, mechanization and irrigation,each American farmer feeds over 155 peopleworldwide. Conventional farming gets more andmore crop per square foot of cultivated land—over 170 bushels of corn per acre in Iowa, for(20) example—which can mean less territory needs tobe converted from wilderness to farmland.And since a third of the planet is already used foragriculture—destroying forests and other wildhabitats along the way—anything that could help us(25) produce more food on less land would seem to begood for the environment.Of course, that’s not how most environmentalistsregard their arugula [a leafy green]. They haveembraced organic food as better for the planet—and(30) healthier and tastier, too—than the stuff produced byagricultural corporations. Environmentalists disdainthe enormous amounts of energy needed and wastecreated by conventional farming, while organicpractices—forgoing artificial fertilizers and chemical(35) pesticides—are considered far more sustainable.Sales of organic food rose 7.7% in 2010, up to $26.7billion—and people are making those purchases fortheir consciences as much as their taste buds.Yet a new meta-analysis in Nature does the math(40) and comes to a hard conclusion: organic farmingyields 25% fewer crops on average than conventionalagriculture. More land is therefore needed toproduce fewer crops—and that means organicfarming may not be as good for the planet as(45) we think.In the Nature analysis, scientists from McGillUniversity in Montreal and the University ofMinnesota performed an analysis of 66 studiescomparing conventional and organic methods across(50) 34 different crop species, from fruits to grains tolegumes. They found that organic farming delivereda lower yield for every crop type, though the disparityvaried widely. For rain-watered legume crops likebeans or perennial crops like fruit trees, organic(55) trailed conventional agriculture by just 5%. Yet formajor cereal crops like corn or wheat, as well as mostvegetables—all of which provide the bulk of theworld’s calories—conventional agricultureoutperformed organics by more than 25%.(60) The main difference is nitrogen, the chemical keyto plant growth. Conventional agriculture makes useof 171 million metric tons of synthetic fertilizer eachyear, and all that nitrogen enables much faster plantgrowth than the slower release of nitrogen from the(65) compost or cover crops used in organic farming.When we talk about a Green Revolution, we reallymean a nitrogen revolution—along with a lot ofwater.But not all the nitrogen used in conventional(70) fertilizer ends up in crops—much of it ends uprunning off the soil and into the oceans, creating vastpolluted dead zones. We’re already putting morenitrogen into the soil than the planet can stand overthe long term. And conventional agriculture also(75) depends heavily on chemical pesticides, which canhave unintended side effects.What that means is that while conventionalagriculture is more efficient—sometimes much moreefficient—than organic farming, there are trade-offs(80) with each. So an ideal global agriculture system, inthe views of the study’s authors, may borrow the bestfrom both systems, as Jonathan Foley of theUniversity of Minnesota explained:The bottom line? Today’s organic farming(85) practices are probably best deployed in fruit andvegetable farms, where growing nutrition (notjust bulk calories) is the primary goal. But fordelivering sheer calories, especially in our staplecrops of wheat, rice, maize, soybeans and so on,(90) conventional farms have the advantage right now.Looking forward, I think we will need to deploydifferent kinds of practices (especially new,mixed approaches that take the best of organic(95) and conventional farming systems) where theyare best suited—geographically, economically,socially, etc.Q.In line 88, “sheer” most nearly meansa)transparent.b)abrupt.c)steep.d)pure.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer?.

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Bryan Walsh, "Whole Food Blues: Why Organic Agriculture May Not Be So Sustainable." ©2012 by Time Inc.When it comes to energy, everyone lovesefficiency. Cutting energy waste is one of those goalsthat both sides of the political divide can agree on,even if they sometimes diverge on how best to get(5) there. Energy efficiency allows us to get more out ofour given resources, which is good for the economyand (mostly) good for the environment as well. Inan increasingly hot and crowded world, the onlysustainable way to live is to get more out of less.(10) Every environmentalist would agree.But change the conversation to food, andsuddenly efficiency doesn’t look so good.Conventional industrial agriculture has becomeincredibly efficient on a simple land to food basis.(15) Thanks to fertilizers, mechanization and irrigation,each American farmer feeds over 155 peopleworldwide. Conventional farming gets more andmore crop per square foot of cultivated land—over 170 bushels of corn per acre in Iowa, for(20) example—which can mean less territory needs tobe converted from wilderness to farmland.And since a third of the planet is already used foragriculture—destroying forests and other wildhabitats along the way—anything that could help us(25) produce more food on less land would seem to begood for the environment.Of course, that’s not how most environmentalistsregard their arugula [a leafy green]. They haveembraced organic food as better for the planet—and(30) healthier and tastier, too—than the stuff produced byagricultural corporations. Environmentalists disdainthe enormous amounts of energy needed and wastecreated by conventional farming, while organicpractices—forgoing artificial fertilizers and chemical(35) pesticides—are considered far more sustainable.Sales of organic food rose 7.7% in 2010, up to $26.7billion—and people are making those purchases fortheir consciences as much as their taste buds.Yet a new meta-analysis in Nature does the math(40) and comes to a hard conclusion: organic farmingyields 25% fewer crops on average than conventionalagriculture. More land is therefore needed toproduce fewer crops—and that means organicfarming may not be as good for the planet as(45) we think.In the Nature analysis, scientists from McGillUniversity in Montreal and the University ofMinnesota performed an analysis of 66 studiescomparing conventional and organic methods across(50) 34 different crop species, from fruits to grains tolegumes. They found that organic farming delivereda lower yield for every crop type, though the disparityvaried widely. For rain-watered legume crops likebeans or perennial crops like fruit trees, organic(55) trailed conventional agriculture by just 5%. Yet formajor cereal crops like corn or wheat, as well as mostvegetables—all of which provide the bulk of theworld’s calories—conventional agricultureoutperformed organics by more than 25%.(60) The main difference is nitrogen, the chemical keyto plant growth. Conventional agriculture makes useof 171 million metric tons of synthetic fertilizer eachyear, and all that nitrogen enables much faster plantgrowth than the slower release of nitrogen from the(65) compost or cover crops used in organic farming.When we talk about a Green Revolution, we reallymean a nitrogen revolution—along with a lot ofwater.But not all the nitrogen used in conventional(70) fertilizer ends up in crops—much of it ends uprunning off the soil and into the oceans, creating vastpolluted dead zones. We’re already putting morenitrogen into the soil than the planet can stand overthe long term. And conventional agriculture also(75) depends heavily on chemical pesticides, which canhave unintended side effects.What that means is that while conventionalagriculture is more efficient—sometimes much moreefficient—than organic farming, there are trade-offs(80) with each. So an ideal global agriculture system, inthe views of the study’s authors, may borrow the bestfrom both systems, as Jonathan Foley of theUniversity of Minnesota explained:The bottom line? Today’s organic farming(85) practices are probably best deployed in fruit andvegetable farms, where growing nutrition (notjust bulk calories) is the primary goal. But fordelivering sheer calories, especially in our staplecrops of wheat, rice, maize, soybeans and so on,(90) conventional farms have the advantage right now.Looking forward, I think we will need to deploydifferent kinds of practices (especially new,mixed approaches that take the best of organic(95) and conventional farming systems) where theyare best suited—geographically, economically,socially, etc.Q.In line 88, “sheer” most nearly meansa)transparent.b)abrupt.c)steep.d)pure.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? for SAT 2025 is part of SAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the SAT exam syllabus. Information about Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Bryan Walsh, "Whole Food Blues: Why Organic Agriculture May Not Be So Sustainable." ©2012 by Time Inc.When it comes to energy, everyone lovesefficiency. Cutting energy waste is one of those goalsthat both sides of the political divide can agree on,even if they sometimes diverge on how best to get(5) there. Energy efficiency allows us to get more out ofour given resources, which is good for the economyand (mostly) good for the environment as well. Inan increasingly hot and crowded world, the onlysustainable way to live is to get more out of less.(10) Every environmentalist would agree.But change the conversation to food, andsuddenly efficiency doesn’t look so good.Conventional industrial agriculture has becomeincredibly efficient on a simple land to food basis.(15) Thanks to fertilizers, mechanization and irrigation,each American farmer feeds over 155 peopleworldwide. Conventional farming gets more andmore crop per square foot of cultivated land—over 170 bushels of corn per acre in Iowa, for(20) example—which can mean less territory needs tobe converted from wilderness to farmland.And since a third of the planet is already used foragriculture—destroying forests and other wildhabitats along the way—anything that could help us(25) produce more food on less land would seem to begood for the environment.Of course, that’s not how most environmentalistsregard their arugula [a leafy green]. They haveembraced organic food as better for the planet—and(30) healthier and tastier, too—than the stuff produced byagricultural corporations. Environmentalists disdainthe enormous amounts of energy needed and wastecreated by conventional farming, while organicpractices—forgoing artificial fertilizers and chemical(35) pesticides—are considered far more sustainable.Sales of organic food rose 7.7% in 2010, up to $26.7billion—and people are making those purchases fortheir consciences as much as their taste buds.Yet a new meta-analysis in Nature does the math(40) and comes to a hard conclusion: organic farmingyields 25% fewer crops on average than conventionalagriculture. More land is therefore needed toproduce fewer crops—and that means organicfarming may not be as good for the planet as(45) we think.In the Nature analysis, scientists from McGillUniversity in Montreal and the University ofMinnesota performed an analysis of 66 studiescomparing conventional and organic methods across(50) 34 different crop species, from fruits to grains tolegumes. They found that organic farming delivereda lower yield for every crop type, though the disparityvaried widely. For rain-watered legume crops likebeans or perennial crops like fruit trees, organic(55) trailed conventional agriculture by just 5%. Yet formajor cereal crops like corn or wheat, as well as mostvegetables—all of which provide the bulk of theworld’s calories—conventional agricultureoutperformed organics by more than 25%.(60) The main difference is nitrogen, the chemical keyto plant growth. Conventional agriculture makes useof 171 million metric tons of synthetic fertilizer eachyear, and all that nitrogen enables much faster plantgrowth than the slower release of nitrogen from the(65) compost or cover crops used in organic farming.When we talk about a Green Revolution, we reallymean a nitrogen revolution—along with a lot ofwater.But not all the nitrogen used in conventional(70) fertilizer ends up in crops—much of it ends uprunning off the soil and into the oceans, creating vastpolluted dead zones. We’re already putting morenitrogen into the soil than the planet can stand overthe long term. And conventional agriculture also(75) depends heavily on chemical pesticides, which canhave unintended side effects.What that means is that while conventionalagriculture is more efficient—sometimes much moreefficient—than organic farming, there are trade-offs(80) with each. So an ideal global agriculture system, inthe views of the study’s authors, may borrow the bestfrom both systems, as Jonathan Foley of theUniversity of Minnesota explained:The bottom line? Today’s organic farming(85) practices are probably best deployed in fruit andvegetable farms, where growing nutrition (notjust bulk calories) is the primary goal. But fordelivering sheer calories, especially in our staplecrops of wheat, rice, maize, soybeans and so on,(90) conventional farms have the advantage right now.Looking forward, I think we will need to deploydifferent kinds of practices (especially new,mixed approaches that take the best of organic(95) and conventional farming systems) where theyare best suited—geographically, economically,socially, etc.Q.In line 88, “sheer” most nearly meansa)transparent.b)abrupt.c)steep.d)pure.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for SAT 2025 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Bryan Walsh, "Whole Food Blues: Why Organic Agriculture May Not Be So Sustainable." ©2012 by Time Inc.When it comes to energy, everyone lovesefficiency. Cutting energy waste is one of those goalsthat both sides of the political divide can agree on,even if they sometimes diverge on how best to get(5) there. Energy efficiency allows us to get more out ofour given resources, which is good for the economyand (mostly) good for the environment as well. Inan increasingly hot and crowded world, the onlysustainable way to live is to get more out of less.(10) Every environmentalist would agree.But change the conversation to food, andsuddenly efficiency doesn’t look so good.Conventional industrial agriculture has becomeincredibly efficient on a simple land to food basis.(15) Thanks to fertilizers, mechanization and irrigation,each American farmer feeds over 155 peopleworldwide. Conventional farming gets more andmore crop per square foot of cultivated land—over 170 bushels of corn per acre in Iowa, for(20) example—which can mean less territory needs tobe converted from wilderness to farmland.And since a third of the planet is already used foragriculture—destroying forests and other wildhabitats along the way—anything that could help us(25) produce more food on less land would seem to begood for the environment.Of course, that’s not how most environmentalistsregard their arugula [a leafy green]. They haveembraced organic food as better for the planet—and(30) healthier and tastier, too—than the stuff produced byagricultural corporations. Environmentalists disdainthe enormous amounts of energy needed and wastecreated by conventional farming, while organicpractices—forgoing artificial fertilizers and chemical(35) pesticides—are considered far more sustainable.Sales of organic food rose 7.7% in 2010, up to $26.7billion—and people are making those purchases fortheir consciences as much as their taste buds.Yet a new meta-analysis in Nature does the math(40) and comes to a hard conclusion: organic farmingyields 25% fewer crops on average than conventionalagriculture. More land is therefore needed toproduce fewer crops—and that means organicfarming may not be as good for the planet as(45) we think.In the Nature analysis, scientists from McGillUniversity in Montreal and the University ofMinnesota performed an analysis of 66 studiescomparing conventional and organic methods across(50) 34 different crop species, from fruits to grains tolegumes. They found that organic farming delivereda lower yield for every crop type, though the disparityvaried widely. For rain-watered legume crops likebeans or perennial crops like fruit trees, organic(55) trailed conventional agriculture by just 5%. Yet formajor cereal crops like corn or wheat, as well as mostvegetables—all of which provide the bulk of theworld’s calories—conventional agricultureoutperformed organics by more than 25%.(60) The main difference is nitrogen, the chemical keyto plant growth. Conventional agriculture makes useof 171 million metric tons of synthetic fertilizer eachyear, and all that nitrogen enables much faster plantgrowth than the slower release of nitrogen from the(65) compost or cover crops used in organic farming.When we talk about a Green Revolution, we reallymean a nitrogen revolution—along with a lot ofwater.But not all the nitrogen used in conventional(70) fertilizer ends up in crops—much of it ends uprunning off the soil and into the oceans, creating vastpolluted dead zones. We’re already putting morenitrogen into the soil than the planet can stand overthe long term. And conventional agriculture also(75) depends heavily on chemical pesticides, which canhave unintended side effects.What that means is that while conventionalagriculture is more efficient—sometimes much moreefficient—than organic farming, there are trade-offs(80) with each. So an ideal global agriculture system, inthe views of the study’s authors, may borrow the bestfrom both systems, as Jonathan Foley of theUniversity of Minnesota explained:The bottom line? Today’s organic farming(85) practices are probably best deployed in fruit andvegetable farms, where growing nutrition (notjust bulk calories) is the primary goal. But fordelivering sheer calories, especially in our staplecrops of wheat, rice, maize, soybeans and so on,(90) conventional farms have the advantage right now.Looking forward, I think we will need to deploydifferent kinds of practices (especially new,mixed approaches that take the best of organic(95) and conventional farming systems) where theyare best suited—geographically, economically,socially, etc.Q.In line 88, “sheer” most nearly meansa)transparent.b)abrupt.c)steep.d)pure.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer?.

Solutions for Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Bryan Walsh, "Whole Food Blues: Why Organic Agriculture May Not Be So Sustainable." ©2012 by Time Inc.When it comes to energy, everyone lovesefficiency. Cutting energy waste is one of those goalsthat both sides of the political divide can agree on,even if they sometimes diverge on how best to get(5) there. Energy efficiency allows us to get more out ofour given resources, which is good for the economyand (mostly) good for the environment as well. Inan increasingly hot and crowded world, the onlysustainable way to live is to get more out of less.(10) Every environmentalist would agree.But change the conversation to food, andsuddenly efficiency doesn’t look so good.Conventional industrial agriculture has becomeincredibly efficient on a simple land to food basis.(15) Thanks to fertilizers, mechanization and irrigation,each American farmer feeds over 155 peopleworldwide. Conventional farming gets more andmore crop per square foot of cultivated land—over 170 bushels of corn per acre in Iowa, for(20) example—which can mean less territory needs tobe converted from wilderness to farmland.And since a third of the planet is already used foragriculture—destroying forests and other wildhabitats along the way—anything that could help us(25) produce more food on less land would seem to begood for the environment.Of course, that’s not how most environmentalistsregard their arugula [a leafy green]. They haveembraced organic food as better for the planet—and(30) healthier and tastier, too—than the stuff produced byagricultural corporations. Environmentalists disdainthe enormous amounts of energy needed and wastecreated by conventional farming, while organicpractices—forgoing artificial fertilizers and chemical(35) pesticides—are considered far more sustainable.Sales of organic food rose 7.7% in 2010, up to $26.7billion—and people are making those purchases fortheir consciences as much as their taste buds.Yet a new meta-analysis in Nature does the math(40) and comes to a hard conclusion: organic farmingyields 25% fewer crops on average than conventionalagriculture. More land is therefore needed toproduce fewer crops—and that means organicfarming may not be as good for the planet as(45) we think.In the Nature analysis, scientists from McGillUniversity in Montreal and the University ofMinnesota performed an analysis of 66 studiescomparing conventional and organic methods across(50) 34 different crop species, from fruits to grains tolegumes. They found that organic farming delivereda lower yield for every crop type, though the disparityvaried widely. For rain-watered legume crops likebeans or perennial crops like fruit trees, organic(55) trailed conventional agriculture by just 5%. Yet formajor cereal crops like corn or wheat, as well as mostvegetables—all of which provide the bulk of theworld’s calories—conventional agricultureoutperformed organics by more than 25%.(60) The main difference is nitrogen, the chemical keyto plant growth. Conventional agriculture makes useof 171 million metric tons of synthetic fertilizer eachyear, and all that nitrogen enables much faster plantgrowth than the slower release of nitrogen from the(65) compost or cover crops used in organic farming.When we talk about a Green Revolution, we reallymean a nitrogen revolution—along with a lot ofwater.But not all the nitrogen used in conventional(70) fertilizer ends up in crops—much of it ends uprunning off the soil and into the oceans, creating vastpolluted dead zones. We’re already putting morenitrogen into the soil than the planet can stand overthe long term. And conventional agriculture also(75) depends heavily on chemical pesticides, which canhave unintended side effects.What that means is that while conventionalagriculture is more efficient—sometimes much moreefficient—than organic farming, there are trade-offs(80) with each. So an ideal global agriculture system, inthe views of the study’s authors, may borrow the bestfrom both systems, as Jonathan Foley of theUniversity of Minnesota explained:The bottom line? Today’s organic farming(85) practices are probably best deployed in fruit andvegetable farms, where growing nutrition (notjust bulk calories) is the primary goal. But fordelivering sheer calories, especially in our staplecrops of wheat, rice, maize, soybeans and so on,(90) conventional farms have the advantage right now.Looking forward, I think we will need to deploydifferent kinds of practices (especially new,mixed approaches that take the best of organic(95) and conventional farming systems) where theyare best suited—geographically, economically,socially, etc.Q.In line 88, “sheer” most nearly meansa)transparent.b)abrupt.c)steep.d)pure.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? in English & in Hindi are available as part of our courses for SAT.

Download more important topics, notes, lectures and mock test series for SAT Exam by signing up for free.

Here you can find the meaning of Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Bryan Walsh, "Whole Food Blues: Why Organic Agriculture May Not Be So Sustainable." ©2012 by Time Inc.When it comes to energy, everyone lovesefficiency. Cutting energy waste is one of those goalsthat both sides of the political divide can agree on,even if they sometimes diverge on how best to get(5) there. Energy efficiency allows us to get more out ofour given resources, which is good for the economyand (mostly) good for the environment as well. Inan increasingly hot and crowded world, the onlysustainable way to live is to get more out of less.(10) Every environmentalist would agree.But change the conversation to food, andsuddenly efficiency doesn’t look so good.Conventional industrial agriculture has becomeincredibly efficient on a simple land to food basis.(15) Thanks to fertilizers, mechanization and irrigation,each American farmer feeds over 155 peopleworldwide. Conventional farming gets more andmore crop per square foot of cultivated land—over 170 bushels of corn per acre in Iowa, for(20) example—which can mean less territory needs tobe converted from wilderness to farmland.And since a third of the planet is already used foragriculture—destroying forests and other wildhabitats along the way—anything that could help us(25) produce more food on less land would seem to begood for the environment.Of course, that’s not how most environmentalistsregard their arugula [a leafy green]. They haveembraced organic food as better for the planet—and(30) healthier and tastier, too—than the stuff produced byagricultural corporations. Environmentalists disdainthe enormous amounts of energy needed and wastecreated by conventional farming, while organicpractices—forgoing artificial fertilizers and chemical(35) pesticides—are considered far more sustainable.Sales of organic food rose 7.7% in 2010, up to $26.7billion—and people are making those purchases fortheir consciences as much as their taste buds.Yet a new meta-analysis in Nature does the math(40) and comes to a hard conclusion: organic farmingyields 25% fewer crops on average than conventionalagriculture. More land is therefore needed toproduce fewer crops—and that means organicfarming may not be as good for the planet as(45) we think.In the Nature analysis, scientists from McGillUniversity in Montreal and the University ofMinnesota performed an analysis of 66 studiescomparing conventional and organic methods across(50) 34 different crop species, from fruits to grains tolegumes. They found that organic farming delivereda lower yield for every crop type, though the disparityvaried widely. For rain-watered legume crops likebeans or perennial crops like fruit trees, organic(55) trailed conventional agriculture by just 5%. Yet formajor cereal crops like corn or wheat, as well as mostvegetables—all of which provide the bulk of theworld’s calories—conventional agricultureoutperformed organics by more than 25%.(60) The main difference is nitrogen, the chemical keyto plant growth. Conventional agriculture makes useof 171 million metric tons of synthetic fertilizer eachyear, and all that nitrogen enables much faster plantgrowth than the slower release of nitrogen from the(65) compost or cover crops used in organic farming.When we talk about a Green Revolution, we reallymean a nitrogen revolution—along with a lot ofwater.But not all the nitrogen used in conventional(70) fertilizer ends up in crops—much of it ends uprunning off the soil and into the oceans, creating vastpolluted dead zones. We’re already putting morenitrogen into the soil than the planet can stand overthe long term. And conventional agriculture also(75) depends heavily on chemical pesticides, which canhave unintended side effects.What that means is that while conventionalagriculture is more efficient—sometimes much moreefficient—than organic farming, there are trade-offs(80) with each. So an ideal global agriculture system, inthe views of the study’s authors, may borrow the bestfrom both systems, as Jonathan Foley of theUniversity of Minnesota explained:The bottom line? Today’s organic farming(85) practices are probably best deployed in fruit andvegetable farms, where growing nutrition (notjust bulk calories) is the primary goal. But fordelivering sheer calories, especially in our staplecrops of wheat, rice, maize, soybeans and so on,(90) conventional farms have the advantage right now.Looking forward, I think we will need to deploydifferent kinds of practices (especially new,mixed approaches that take the best of organic(95) and conventional farming systems) where theyare best suited—geographically, economically,socially, etc.Q.In line 88, “sheer” most nearly meansa)transparent.b)abrupt.c)steep.d)pure.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? defined & explained in the simplest way possible. Besides giving the explanation of

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Bryan Walsh, "Whole Food Blues: Why Organic Agriculture May Not Be So Sustainable." ©2012 by Time Inc.When it comes to energy, everyone lovesefficiency. Cutting energy waste is one of those goalsthat both sides of the political divide can agree on,even if they sometimes diverge on how best to get(5) there. Energy efficiency allows us to get more out ofour given resources, which is good for the economyand (mostly) good for the environment as well. Inan increasingly hot and crowded world, the onlysustainable way to live is to get more out of less.(10) Every environmentalist would agree.But change the conversation to food, andsuddenly efficiency doesn’t look so good.Conventional industrial agriculture has becomeincredibly efficient on a simple land to food basis.(15) Thanks to fertilizers, mechanization and irrigation,each American farmer feeds over 155 peopleworldwide. Conventional farming gets more andmore crop per square foot of cultivated land—over 170 bushels of corn per acre in Iowa, for(20) example—which can mean less territory needs tobe converted from wilderness to farmland.And since a third of the planet is already used foragriculture—destroying forests and other wildhabitats along the way—anything that could help us(25) produce more food on less land would seem to begood for the environment.Of course, that’s not how most environmentalistsregard their arugula [a leafy green]. They haveembraced organic food as better for the planet—and(30) healthier and tastier, too—than the stuff produced byagricultural corporations. Environmentalists disdainthe enormous amounts of energy needed and wastecreated by conventional farming, while organicpractices—forgoing artificial fertilizers and chemical(35) pesticides—are considered far more sustainable.Sales of organic food rose 7.7% in 2010, up to $26.7billion—and people are making those purchases fortheir consciences as much as their taste buds.Yet a new meta-analysis in Nature does the math(40) and comes to a hard conclusion: organic farmingyields 25% fewer crops on average than conventionalagriculture. More land is therefore needed toproduce fewer crops—and that means organicfarming may not be as good for the planet as(45) we think.In the Nature analysis, scientists from McGillUniversity in Montreal and the University ofMinnesota performed an analysis of 66 studiescomparing conventional and organic methods across(50) 34 different crop species, from fruits to grains tolegumes. They found that organic farming delivereda lower yield for every crop type, though the disparityvaried widely. For rain-watered legume crops likebeans or perennial crops like fruit trees, organic(55) trailed conventional agriculture by just 5%. Yet formajor cereal crops like corn or wheat, as well as mostvegetables—all of which provide the bulk of theworld’s calories—conventional agricultureoutperformed organics by more than 25%.(60) The main difference is nitrogen, the chemical keyto plant growth. Conventional agriculture makes useof 171 million metric tons of synthetic fertilizer eachyear, and all that nitrogen enables much faster plantgrowth than the slower release of nitrogen from the(65) compost or cover crops used in organic farming.When we talk about a Green Revolution, we reallymean a nitrogen revolution—along with a lot ofwater.But not all the nitrogen used in conventional(70) fertilizer ends up in crops—much of it ends uprunning off the soil and into the oceans, creating vastpolluted dead zones. We’re already putting morenitrogen into the soil than the planet can stand overthe long term. And conventional agriculture also(75) depends heavily on chemical pesticides, which canhave unintended side effects.What that means is that while conventionalagriculture is more efficient—sometimes much moreefficient—than organic farming, there are trade-offs(80) with each. So an ideal global agriculture system, inthe views of the study’s authors, may borrow the bestfrom both systems, as Jonathan Foley of theUniversity of Minnesota explained:The bottom line? Today’s organic farming(85) practices are probably best deployed in fruit andvegetable farms, where growing nutrition (notjust bulk calories) is the primary goal. But fordelivering sheer calories, especially in our staplecrops of wheat, rice, maize, soybeans and so on,(90) conventional farms have the advantage right now.Looking forward, I think we will need to deploydifferent kinds of practices (especially new,mixed approaches that take the best of organic(95) and conventional farming systems) where theyare best suited—geographically, economically,socially, etc.Q.In line 88, “sheer” most nearly meansa)transparent.b)abrupt.c)steep.d)pure.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer?, a detailed solution for Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Bryan Walsh, "Whole Food Blues: Why Organic Agriculture May Not Be So Sustainable." ©2012 by Time Inc.When it comes to energy, everyone lovesefficiency. Cutting energy waste is one of those goalsthat both sides of the political divide can agree on,even if they sometimes diverge on how best to get(5) there. Energy efficiency allows us to get more out ofour given resources, which is good for the economyand (mostly) good for the environment as well. Inan increasingly hot and crowded world, the onlysustainable way to live is to get more out of less.(10) Every environmentalist would agree.But change the conversation to food, andsuddenly efficiency doesn’t look so good.Conventional industrial agriculture has becomeincredibly efficient on a simple land to food basis.(15) Thanks to fertilizers, mechanization and irrigation,each American farmer feeds over 155 peopleworldwide. Conventional farming gets more andmore crop per square foot of cultivated land—over 170 bushels of corn per acre in Iowa, for(20) example—which can mean less territory needs tobe converted from wilderness to farmland.And since a third of the planet is already used foragriculture—destroying forests and other wildhabitats along the way—anything that could help us(25) produce more food on less land would seem to begood for the environment.Of course, that’s not how most environmentalistsregard their arugula [a leafy green]. They haveembraced organic food as better for the planet—and(30) healthier and tastier, too—than the stuff produced byagricultural corporations. Environmentalists disdainthe enormous amounts of energy needed and wastecreated by conventional farming, while organicpractices—forgoing artificial fertilizers and chemical(35) pesticides—are considered far more sustainable.Sales of organic food rose 7.7% in 2010, up to $26.7billion—and people are making those purchases fortheir consciences as much as their taste buds.Yet a new meta-analysis in Nature does the math(40) and comes to a hard conclusion: organic farmingyields 25% fewer crops on average than conventionalagriculture. More land is therefore needed toproduce fewer crops—and that means organicfarming may not be as good for the planet as(45) we think.In the Nature analysis, scientists from McGillUniversity in Montreal and the University ofMinnesota performed an analysis of 66 studiescomparing conventional and organic methods across(50) 34 different crop species, from fruits to grains tolegumes. They found that organic farming delivereda lower yield for every crop type, though the disparityvaried widely. For rain-watered legume crops likebeans or perennial crops like fruit trees, organic(55) trailed conventional agriculture by just 5%. Yet formajor cereal crops like corn or wheat, as well as mostvegetables—all of which provide the bulk of theworld’s calories—conventional agricultureoutperformed organics by more than 25%.(60) The main difference is nitrogen, the chemical keyto plant growth. Conventional agriculture makes useof 171 million metric tons of synthetic fertilizer eachyear, and all that nitrogen enables much faster plantgrowth than the slower release of nitrogen from the(65) compost or cover crops used in organic farming.When we talk about a Green Revolution, we reallymean a nitrogen revolution—along with a lot ofwater.But not all the nitrogen used in conventional(70) fertilizer ends up in crops—much of it ends uprunning off the soil and into the oceans, creating vastpolluted dead zones. We’re already putting morenitrogen into the soil than the planet can stand overthe long term. And conventional agriculture also(75) depends heavily on chemical pesticides, which canhave unintended side effects.What that means is that while conventionalagriculture is more efficient—sometimes much moreefficient—than organic farming, there are trade-offs(80) with each. So an ideal global agriculture system, inthe views of the study’s authors, may borrow the bestfrom both systems, as Jonathan Foley of theUniversity of Minnesota explained:The bottom line? Today’s organic farming(85) practices are probably best deployed in fruit andvegetable farms, where growing nutrition (notjust bulk calories) is the primary goal. But fordelivering sheer calories, especially in our staplecrops of wheat, rice, maize, soybeans and so on,(90) conventional farms have the advantage right now.Looking forward, I think we will need to deploydifferent kinds of practices (especially new,mixed approaches that take the best of organic(95) and conventional farming systems) where theyare best suited—geographically, economically,socially, etc.Q.In line 88, “sheer” most nearly meansa)transparent.b)abrupt.c)steep.d)pure.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? has been provided alongside types of Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Bryan Walsh, "Whole Food Blues: Why Organic Agriculture May Not Be So Sustainable." ©2012 by Time Inc.When it comes to energy, everyone lovesefficiency. Cutting energy waste is one of those goalsthat both sides of the political divide can agree on,even if they sometimes diverge on how best to get(5) there. Energy efficiency allows us to get more out ofour given resources, which is good for the economyand (mostly) good for the environment as well. Inan increasingly hot and crowded world, the onlysustainable way to live is to get more out of less.(10) Every environmentalist would agree.But change the conversation to food, andsuddenly efficiency doesn’t look so good.Conventional industrial agriculture has becomeincredibly efficient on a simple land to food basis.(15) Thanks to fertilizers, mechanization and irrigation,each American farmer feeds over 155 peopleworldwide. Conventional farming gets more andmore crop per square foot of cultivated land—over 170 bushels of corn per acre in Iowa, for(20) example—which can mean less territory needs tobe converted from wilderness to farmland.And since a third of the planet is already used foragriculture—destroying forests and other wildhabitats along the way—anything that could help us(25) produce more food on less land would seem to begood for the environment.Of course, that’s not how most environmentalistsregard their arugula [a leafy green]. They haveembraced organic food as better for the planet—and(30) healthier and tastier, too—than the stuff produced byagricultural corporations. Environmentalists disdainthe enormous amounts of energy needed and wastecreated by conventional farming, while organicpractices—forgoing artificial fertilizers and chemical(35) pesticides—are considered far more sustainable.Sales of organic food rose 7.7% in 2010, up to $26.7billion—and people are making those purchases fortheir consciences as much as their taste buds.Yet a new meta-analysis in Nature does the math(40) and comes to a hard conclusion: organic farmingyields 25% fewer crops on average than conventionalagriculture. More land is therefore needed toproduce fewer crops—and that means organicfarming may not be as good for the planet as(45) we think.In the Nature analysis, scientists from McGillUniversity in Montreal and the University ofMinnesota performed an analysis of 66 studiescomparing conventional and organic methods across(50) 34 different crop species, from fruits to grains tolegumes. They found that organic farming delivereda lower yield for every crop type, though the disparityvaried widely. For rain-watered legume crops likebeans or perennial crops like fruit trees, organic(55) trailed conventional agriculture by just 5%. Yet formajor cereal crops like corn or wheat, as well as mostvegetables—all of which provide the bulk of theworld’s calories—conventional agricultureoutperformed organics by more than 25%.(60) The main difference is nitrogen, the chemical keyto plant growth. Conventional agriculture makes useof 171 million metric tons of synthetic fertilizer eachyear, and all that nitrogen enables much faster plantgrowth than the slower release of nitrogen from the(65) compost or cover crops used in organic farming.When we talk about a Green Revolution, we reallymean a nitrogen revolution—along with a lot ofwater.But not all the nitrogen used in conventional(70) fertilizer ends up in crops—much of it ends uprunning off the soil and into the oceans, creating vastpolluted dead zones. We’re already putting morenitrogen into the soil than the planet can stand overthe long term. And conventional agriculture also(75) depends heavily on chemical pesticides, which canhave unintended side effects.What that means is that while conventionalagriculture is more efficient—sometimes much moreefficient—than organic farming, there are trade-offs(80) with each. So an ideal global agriculture system, inthe views of the study’s authors, may borrow the bestfrom both systems, as Jonathan Foley of theUniversity of Minnesota explained:The bottom line? Today’s organic farming(85) practices are probably best deployed in fruit andvegetable farms, where growing nutrition (notjust bulk calories) is the primary goal. But fordelivering sheer calories, especially in our staplecrops of wheat, rice, maize, soybeans and so on,(90) conventional farms have the advantage right now.Looking forward, I think we will need to deploydifferent kinds of practices (especially new,mixed approaches that take the best of organic(95) and conventional farming systems) where theyare best suited—geographically, economically,socially, etc.Q.In line 88, “sheer” most nearly meansa)transparent.b)abrupt.c)steep.d)pure.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? theory, EduRev gives you an

ample number of questions to practice Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Bryan Walsh, "Whole Food Blues: Why Organic Agriculture May Not Be So Sustainable." ©2012 by Time Inc.When it comes to energy, everyone lovesefficiency. Cutting energy waste is one of those goalsthat both sides of the political divide can agree on,even if they sometimes diverge on how best to get(5) there. Energy efficiency allows us to get more out ofour given resources, which is good for the economyand (mostly) good for the environment as well. Inan increasingly hot and crowded world, the onlysustainable way to live is to get more out of less.(10) Every environmentalist would agree.But change the conversation to food, andsuddenly efficiency doesn’t look so good.Conventional industrial agriculture has becomeincredibly efficient on a simple land to food basis.(15) Thanks to fertilizers, mechanization and irrigation,each American farmer feeds over 155 peopleworldwide. Conventional farming gets more andmore crop per square foot of cultivated land—over 170 bushels of corn per acre in Iowa, for(20) example—which can mean less territory needs tobe converted from wilderness to farmland.And since a third of the planet is already used foragriculture—destroying forests and other wildhabitats along the way—anything that could help us(25) produce more food on less land would seem to begood for the environment.Of course, that’s not how most environmentalistsregard their arugula [a leafy green]. They haveembraced organic food as better for the planet—and(30) healthier and tastier, too—than the stuff produced byagricultural corporations. Environmentalists disdainthe enormous amounts of energy needed and wastecreated by conventional farming, while organicpractices—forgoing artificial fertilizers and chemical(35) pesticides—are considered far more sustainable.Sales of organic food rose 7.7% in 2010, up to $26.7billion—and people are making those purchases fortheir consciences as much as their taste buds.Yet a new meta-analysis in Nature does the math(40) and comes to a hard conclusion: organic farmingyields 25% fewer crops on average than conventionalagriculture. More land is therefore needed toproduce fewer crops—and that means organicfarming may not be as good for the planet as(45) we think.In the Nature analysis, scientists from McGillUniversity in Montreal and the University ofMinnesota performed an analysis of 66 studiescomparing conventional and organic methods across(50) 34 different crop species, from fruits to grains tolegumes. They found that organic farming delivereda lower yield for every crop type, though the disparityvaried widely. For rain-watered legume crops likebeans or perennial crops like fruit trees, organic(55) trailed conventional agriculture by just 5%. Yet formajor cereal crops like corn or wheat, as well as mostvegetables—all of which provide the bulk of theworld’s calories—conventional agricultureoutperformed organics by more than 25%.(60) The main difference is nitrogen, the chemical keyto plant growth. Conventional agriculture makes useof 171 million metric tons of synthetic fertilizer eachyear, and all that nitrogen enables much faster plantgrowth than the slower release of nitrogen from the(65) compost or cover crops used in organic farming.When we talk about a Green Revolution, we reallymean a nitrogen revolution—along with a lot ofwater.But not all the nitrogen used in conventional(70) fertilizer ends up in crops—much of it ends uprunning off the soil and into the oceans, creating vastpolluted dead zones. We’re already putting morenitrogen into the soil than the planet can stand overthe long term. And conventional agriculture also(75) depends heavily on chemical pesticides, which canhave unintended side effects.What that means is that while conventionalagriculture is more efficient—sometimes much moreefficient—than organic farming, there are trade-offs(80) with each. So an ideal global agriculture system, inthe views of the study’s authors, may borrow the bestfrom both systems, as Jonathan Foley of theUniversity of Minnesota explained:The bottom line? Today’s organic farming(85) practices are probably best deployed in fruit andvegetable farms, where growing nutrition (notjust bulk calories) is the primary goal. But fordelivering sheer calories, especially in our staplecrops of wheat, rice, maize, soybeans and so on,(90) conventional farms have the advantage right now.Looking forward, I think we will need to deploydifferent kinds of practices (especially new,mixed approaches that take the best of organic(95) and conventional farming systems) where theyare best suited—geographically, economically,socially, etc.Q.In line 88, “sheer” most nearly meansa)transparent.b)abrupt.c)steep.d)pure.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? tests, examples and also practice SAT tests.

|

Explore Courses for SAT exam

|

|

Signup for Free!

Signup to see your scores go up within 7 days! Learn & Practice with 1000+ FREE Notes, Videos & Tests.