SAT Exam > SAT Questions > Question based on the following passage and s...

Start Learning for Free

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from John Bohannon, "Why You Shouldn't Trust Internet Comments." ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The “wisdom of crowds” has become a mantra of

the Internet age. Need to choose a new vacuum

cleaner? Check out the reviews on online merchant

Amazon. But a new study suggests that such online

(5) scores don’t always reveal the best choice. A massive

controlled experiment of Web users finds that such

ratings are highly susceptible to irrational “herd

behavior”—and that the herd can be manipulated.

Sometimes the crowd really is wiser than you. The

(10) classic examples are guessing the weight of a bull or

the number of gumballs in a jar. Your guess is

probably going to be far from the mark, whereas the

average of many people’s choices is remarkably close

to the true number.

(15) But what happens when the goal is to judge

something less tangible, such as the quality or worth

of a product? According to one theory, the wisdom

of the crowd still holds—measuring the aggregate of

people’s opinions produces a stable, reliable

(20) value. Skeptics, however, argue that people’s

opinions are easily swayed by those of others. So

nudging a crowd early on by presenting contrary

opinions—for example, exposing them to some very

good or very bad attitudes—will steer the crowd in a

(25) different direction. To test which hypothesis is true,

you would need to manipulate huge numbers of

people, exposing them to false information and

determining how it affects their opinions.

A team led by Sinan Aral, a network scientist at

(30) the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in

Cambridge, did exactly that. Aral has been secretly

working with a popular website that aggregates news

stories. The website allows users to make comments

about news stories and vote each other’s comments

(35) up or down. The vote tallies are visible as a number

next to each comment, and the position of the

comments is chronological. (Stories on the site get an

average of about ten comments and about three votes

per comment.) It’s a follow-up to his experiment

(40) using people’s ratings of movies to measure how

much individual people influence each other online

(answer: a lot). This time, he wanted to know how

much the crowd influences the individual, and

whether it can be controlled from outside.

(45) For five months, every comment submitted by a

user randomly received an “up” vote (positive); a

“down” vote (negative); or as a control, no vote at all.

The team then observed how users rated those

comments. The users generated more than

(50) 100,000 comments that were viewed more than

10 million times and rated more than 300,000 times

by other users.

At least when it comes to comments on news

sites, the crowd is more herdlike than wise.

(55) Comments that received fake positive votes from the

researchers were 32% more likely to receive more

positive votes compared with a control, the team

reports. And those comments were no more likely

than the control to be down-voted by the next viewer

(60) to see them. By the end of the study, positively

manipulated comments got an overall boost of about

25%. However, the same did not hold true for negative

manipulation. The ratings of comments that

got a fake down vote were usually negated by an up

(65) vote by the next user to see them.

“Our experiment does not reveal the psychology

behind people’s decisions,” Aral says, “but an

intuitive explanation is that people are more

skeptical of negative social influence. They’re more

(70) willing to go along with positive opinions from other

people.”

Duncan Watts, a network scientist at Microsoft

Research in New York City, agrees with that

conclusion. “[But] one question is whether the

(75) positive [herding] bias is specific to this site” or true

in general, Watts says. He points out that the

category of the news items in the experiment had a

strong effect on how much people could be

manipulated. “I would have thought that ‘business’ is

(80) pretty similar to ‘economics,’ yet they find a much

stronger effect (almost 50% stronger) for the former

than the latter. What explains this difference? If we’re

going to apply these findings in the real world, we’ll

need to know the answers.”

(85) Will companies be able to boost their products by

manipulating online ratings on a massive scale?

“That is easier said than done,” Watts says. If people

detect—or learn—that comments on a website are

being manipulated, the herd may spook and leave

(90) entirely.

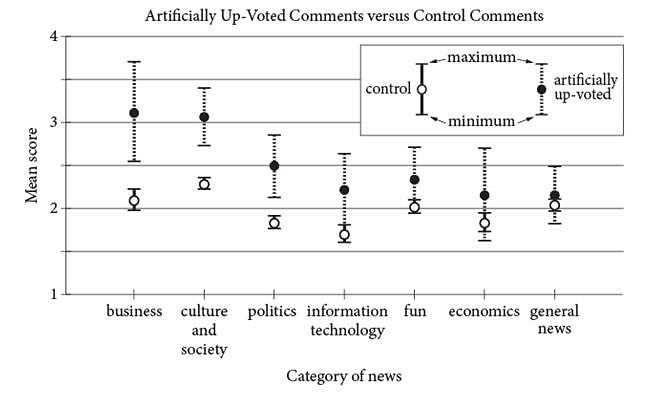

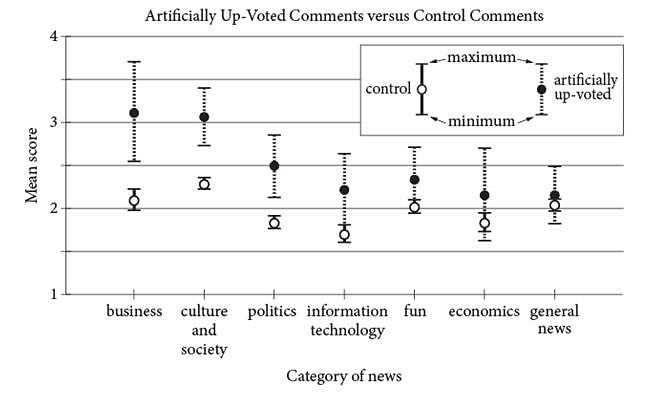

Mean score: mean of scores for the comments in each category, with the score for each comment being determined by the number of positive votes from website users minus the number of negative votes

Adapted from Lev Muchnik, Sinan Aral, and Sean J. Taylor, “Social Influence Bias: A Randomized Experiment.” ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.

This passage is adapted from John Bohannon, "Why You Shouldn't Trust Internet Comments." ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The “wisdom of crowds” has become a mantra of

the Internet age. Need to choose a new vacuum

cleaner? Check out the reviews on online merchant

Amazon. But a new study suggests that such online

(5) scores don’t always reveal the best choice. A massive

controlled experiment of Web users finds that such

ratings are highly susceptible to irrational “herd

behavior”—and that the herd can be manipulated.

Sometimes the crowd really is wiser than you. The

(10) classic examples are guessing the weight of a bull or

the number of gumballs in a jar. Your guess is

probably going to be far from the mark, whereas the

average of many people’s choices is remarkably close

to the true number.

(15) But what happens when the goal is to judge

something less tangible, such as the quality or worth

of a product? According to one theory, the wisdom

of the crowd still holds—measuring the aggregate of

people’s opinions produces a stable, reliable

(20) value. Skeptics, however, argue that people’s

opinions are easily swayed by those of others. So

nudging a crowd early on by presenting contrary

opinions—for example, exposing them to some very

good or very bad attitudes—will steer the crowd in a

(25) different direction. To test which hypothesis is true,

you would need to manipulate huge numbers of

people, exposing them to false information and

determining how it affects their opinions.

A team led by Sinan Aral, a network scientist at

(30) the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in

Cambridge, did exactly that. Aral has been secretly

working with a popular website that aggregates news

stories. The website allows users to make comments

about news stories and vote each other’s comments

(35) up or down. The vote tallies are visible as a number

next to each comment, and the position of the

comments is chronological. (Stories on the site get an

average of about ten comments and about three votes

per comment.) It’s a follow-up to his experiment

(40) using people’s ratings of movies to measure how

much individual people influence each other online

(answer: a lot). This time, he wanted to know how

much the crowd influences the individual, and

whether it can be controlled from outside.

(45) For five months, every comment submitted by a

user randomly received an “up” vote (positive); a

“down” vote (negative); or as a control, no vote at all.

The team then observed how users rated those

comments. The users generated more than

(50) 100,000 comments that were viewed more than

10 million times and rated more than 300,000 times

by other users.

At least when it comes to comments on news

sites, the crowd is more herdlike than wise.

(55) Comments that received fake positive votes from the

researchers were 32% more likely to receive more

positive votes compared with a control, the team

reports. And those comments were no more likely

than the control to be down-voted by the next viewer

(60) to see them. By the end of the study, positively

manipulated comments got an overall boost of about

25%. However, the same did not hold true for negative

manipulation. The ratings of comments that

got a fake down vote were usually negated by an up

(65) vote by the next user to see them.

“Our experiment does not reveal the psychology

behind people’s decisions,” Aral says, “but an

intuitive explanation is that people are more

skeptical of negative social influence. They’re more

(70) willing to go along with positive opinions from other

people.”

Duncan Watts, a network scientist at Microsoft

Research in New York City, agrees with that

conclusion. “[But] one question is whether the

(75) positive [herding] bias is specific to this site” or true

in general, Watts says. He points out that the

category of the news items in the experiment had a

strong effect on how much people could be

manipulated. “I would have thought that ‘business’ is

(80) pretty similar to ‘economics,’ yet they find a much

stronger effect (almost 50% stronger) for the former

than the latter. What explains this difference? If we’re

going to apply these findings in the real world, we’ll

need to know the answers.”

(85) Will companies be able to boost their products by

manipulating online ratings on a massive scale?

“That is easier said than done,” Watts says. If people

detect—or learn—that comments on a website are

being manipulated, the herd may spook and leave

(90) entirely.

Mean score: mean of scores for the comments in each category, with the score for each comment being determined by the number of positive votes from website users minus the number of negative votes

Adapted from Lev Muchnik, Sinan Aral, and Sean J. Taylor, “Social Influence Bias: A Randomized Experiment.” ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Q. Which choice best supports the view of the “skeptics” (line 20)?

- a)Lines 55-58 (“Comments... reports”)

- b)Lines 58-60 (“And... them”)

- c)Lines 63-65 (“The ratings... them”)

- d)Lines 76-79 (“He... manipulated”)

Correct answer is option 'A'. Can you explain this answer?

Most Upvoted Answer

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Thi...

Choice A is the best answer. In the passage, the author explains that those who are skeptical of the theory that "measuring the aggregate of people's opinions produces a stable, reliable value" (lines 1820) believe that "people's opinions are easily swayed by those of others" (lines 20-21). This idea is best supported in lines 55-58, which describe a finding from a study of opinions in crowds: "Comments that received fake positive votes from the researchers were 32% more likely to receive more positive votes compared with a control, the team reports." In other words, people were more likely to give a positive vote when they thought other people had given positive votes.

Choices B, C, and D are incorrect because the lines cited do not provide support for the skeptics' idea that people's opinions are easily influenced by the thoughts of others. Instead, they cite findings concerning people giving ratings different from those already given (choices B and C) and share an observation that the degree to which others can be influenced depends in part on the context of the situation (choice D).

Choices B, C, and D are incorrect because the lines cited do not provide support for the skeptics' idea that people's opinions are easily influenced by the thoughts of others. Instead, they cite findings concerning people giving ratings different from those already given (choices B and C) and share an observation that the degree to which others can be influenced depends in part on the context of the situation (choice D).

|

Explore Courses for SAT exam

|

|

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from John Bohannon, "Why You Shouldnt Trust Internet Comments." ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.The “wisdom of crowds” has become a mantra ofthe Internet age. Need to choose a new vacuumcleaner? Check out the reviews on online merchantAmazon. But a new study suggests that such online(5) scores don’t always reveal the best choice. A massivecontrolled experiment of Web users finds that suchratings are highly susceptible to irrational “herdbehavior”—and that the herd can be manipulated.Sometimes the crowd really is wiser than you. The(10) classic examples are guessing the weight of a bull orthe number of gumballs in a jar. Your guess isprobably going to be far from the mark, whereas theaverage of many people’s choices is remarkably closeto the true number.(15) But what happens when the goal is to judgesomething less tangible, such as the quality or worthof a product? According to one theory, the wisdomof the crowd still holds—measuring the aggregate ofpeople’s opinions produces a stable, reliable(20) value. Skeptics, however, argue that people’sopinions are easily swayed by those of others. Sonudging a crowd early on by presenting contraryopinions—for example, exposing them to some verygood or very bad attitudes—will steer the crowd in a(25) different direction. To test which hypothesis is true,you would need to manipulate huge numbers ofpeople, exposing them to false information anddetermining how it affects their opinions.A team led by Sinan Aral, a network scientist at(30) the Massachusetts Institute of Technology inCambridge, did exactly that. Aral has been secretlyworking with a popular website that aggregates newsstories. The website allows users to make commentsabout news stories and vote each other’s comments(35) up or down. The vote tallies are visible as a numbernext to each comment, and the position of thecomments is chronological. (Stories on the site get anaverage of about ten comments and about three votesper comment.) It’s a follow-up to his experiment(40) using people’s ratings of movies to measure howmuch individual people influence each other online(answer: a lot). This time, he wanted to know howmuch the crowd influences the individual, andwhether it can be controlled from outside.(45) For five months, every comment submitted by auser randomly received an “up” vote (positive); a“down” vote (negative); or as a control, no vote at all.The team then observed how users rated thosecomments. The users generated more than(50) 100,000 comments that were viewed more than10 million times and rated more than 300,000 timesby other users.At least when it comes to comments on newssites, the crowd is more herdlike than wise.(55) Comments that received fake positive votes from theresearchers were 32% more likely to receive morepositive votes compared with a control, the teamreports. And those comments were no more likelythan the control to be down-voted by the next viewer(60) to see them. By the end of the study, positivelymanipulated comments got an overall boost of about25%. However, the same did not hold true for negativemanipulation. The ratings of comments thatgot a fake down vote were usually negated by an up(65) vote by the next user to see them.“Our experiment does not reveal the psychologybehind people’s decisions,” Aral says, “but anintuitive explanation is that people are moreskeptical of negative social influence. They’re more(70) willing to go along with positive opinions from otherpeople.”Duncan Watts, a network scientist at MicrosoftResearch in New York City, agrees with thatconclusion. “[But] one question is whether the(75) positive [herding] bias is specific to this site” or truein general, Watts says. He points out that thecategory of the news items in the experiment had astrong effect on how much people could bemanipulated. “I would have thought that ‘business’ is(80) pretty similar to ‘economics,’ yet they find a muchstronger effect (almost 50% stronger) for the formerthan the latter. What explains this difference? If we’regoing to apply these findings in the real world, we’llneed to know the answers.”(85) Will companies be able to boost their products bymanipulating online ratings on a massive scale?“That is easier said than done,” Watts says. If peopledetect—or learn—that comments on a website arebeing manipulated, the herd may spook and leave(90) entirely.Mean score: mean of scores for the comments in each category, with the score for each comment being determined by the number of positive votes from website users minus the number of negative votesAdapted from Lev Muchnik, Sinan Aral, and Sean J. Taylor, “Social Influence Bias: A Randomized Experiment.” ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.Q.Which choice best supports the view of the “skeptics” (line 20)?a)Lines 55-58 (“Comments... reports”)b)Lines 58-60 (“And... them”)c)Lines 63-65 (“The ratings... them”)d)Lines 76-79 (“He... manipulated”)Correct answer is option 'A'. Can you explain this answer?

Question Description

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from John Bohannon, "Why You Shouldnt Trust Internet Comments." ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.The “wisdom of crowds” has become a mantra ofthe Internet age. Need to choose a new vacuumcleaner? Check out the reviews on online merchantAmazon. But a new study suggests that such online(5) scores don’t always reveal the best choice. A massivecontrolled experiment of Web users finds that suchratings are highly susceptible to irrational “herdbehavior”—and that the herd can be manipulated.Sometimes the crowd really is wiser than you. The(10) classic examples are guessing the weight of a bull orthe number of gumballs in a jar. Your guess isprobably going to be far from the mark, whereas theaverage of many people’s choices is remarkably closeto the true number.(15) But what happens when the goal is to judgesomething less tangible, such as the quality or worthof a product? According to one theory, the wisdomof the crowd still holds—measuring the aggregate ofpeople’s opinions produces a stable, reliable(20) value. Skeptics, however, argue that people’sopinions are easily swayed by those of others. Sonudging a crowd early on by presenting contraryopinions—for example, exposing them to some verygood or very bad attitudes—will steer the crowd in a(25) different direction. To test which hypothesis is true,you would need to manipulate huge numbers ofpeople, exposing them to false information anddetermining how it affects their opinions.A team led by Sinan Aral, a network scientist at(30) the Massachusetts Institute of Technology inCambridge, did exactly that. Aral has been secretlyworking with a popular website that aggregates newsstories. The website allows users to make commentsabout news stories and vote each other’s comments(35) up or down. The vote tallies are visible as a numbernext to each comment, and the position of thecomments is chronological. (Stories on the site get anaverage of about ten comments and about three votesper comment.) It’s a follow-up to his experiment(40) using people’s ratings of movies to measure howmuch individual people influence each other online(answer: a lot). This time, he wanted to know howmuch the crowd influences the individual, andwhether it can be controlled from outside.(45) For five months, every comment submitted by auser randomly received an “up” vote (positive); a“down” vote (negative); or as a control, no vote at all.The team then observed how users rated thosecomments. The users generated more than(50) 100,000 comments that were viewed more than10 million times and rated more than 300,000 timesby other users.At least when it comes to comments on newssites, the crowd is more herdlike than wise.(55) Comments that received fake positive votes from theresearchers were 32% more likely to receive morepositive votes compared with a control, the teamreports. And those comments were no more likelythan the control to be down-voted by the next viewer(60) to see them. By the end of the study, positivelymanipulated comments got an overall boost of about25%. However, the same did not hold true for negativemanipulation. The ratings of comments thatgot a fake down vote were usually negated by an up(65) vote by the next user to see them.“Our experiment does not reveal the psychologybehind people’s decisions,” Aral says, “but anintuitive explanation is that people are moreskeptical of negative social influence. They’re more(70) willing to go along with positive opinions from otherpeople.”Duncan Watts, a network scientist at MicrosoftResearch in New York City, agrees with thatconclusion. “[But] one question is whether the(75) positive [herding] bias is specific to this site” or truein general, Watts says. He points out that thecategory of the news items in the experiment had astrong effect on how much people could bemanipulated. “I would have thought that ‘business’ is(80) pretty similar to ‘economics,’ yet they find a muchstronger effect (almost 50% stronger) for the formerthan the latter. What explains this difference? If we’regoing to apply these findings in the real world, we’llneed to know the answers.”(85) Will companies be able to boost their products bymanipulating online ratings on a massive scale?“That is easier said than done,” Watts says. If peopledetect—or learn—that comments on a website arebeing manipulated, the herd may spook and leave(90) entirely.Mean score: mean of scores for the comments in each category, with the score for each comment being determined by the number of positive votes from website users minus the number of negative votesAdapted from Lev Muchnik, Sinan Aral, and Sean J. Taylor, “Social Influence Bias: A Randomized Experiment.” ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.Q.Which choice best supports the view of the “skeptics” (line 20)?a)Lines 55-58 (“Comments... reports”)b)Lines 58-60 (“And... them”)c)Lines 63-65 (“The ratings... them”)d)Lines 76-79 (“He... manipulated”)Correct answer is option 'A'. Can you explain this answer? for SAT 2025 is part of SAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the SAT exam syllabus. Information about Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from John Bohannon, "Why You Shouldnt Trust Internet Comments." ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.The “wisdom of crowds” has become a mantra ofthe Internet age. Need to choose a new vacuumcleaner? Check out the reviews on online merchantAmazon. But a new study suggests that such online(5) scores don’t always reveal the best choice. A massivecontrolled experiment of Web users finds that suchratings are highly susceptible to irrational “herdbehavior”—and that the herd can be manipulated.Sometimes the crowd really is wiser than you. The(10) classic examples are guessing the weight of a bull orthe number of gumballs in a jar. Your guess isprobably going to be far from the mark, whereas theaverage of many people’s choices is remarkably closeto the true number.(15) But what happens when the goal is to judgesomething less tangible, such as the quality or worthof a product? According to one theory, the wisdomof the crowd still holds—measuring the aggregate ofpeople’s opinions produces a stable, reliable(20) value. Skeptics, however, argue that people’sopinions are easily swayed by those of others. Sonudging a crowd early on by presenting contraryopinions—for example, exposing them to some verygood or very bad attitudes—will steer the crowd in a(25) different direction. To test which hypothesis is true,you would need to manipulate huge numbers ofpeople, exposing them to false information anddetermining how it affects their opinions.A team led by Sinan Aral, a network scientist at(30) the Massachusetts Institute of Technology inCambridge, did exactly that. Aral has been secretlyworking with a popular website that aggregates newsstories. The website allows users to make commentsabout news stories and vote each other’s comments(35) up or down. The vote tallies are visible as a numbernext to each comment, and the position of thecomments is chronological. (Stories on the site get anaverage of about ten comments and about three votesper comment.) It’s a follow-up to his experiment(40) using people’s ratings of movies to measure howmuch individual people influence each other online(answer: a lot). This time, he wanted to know howmuch the crowd influences the individual, andwhether it can be controlled from outside.(45) For five months, every comment submitted by auser randomly received an “up” vote (positive); a“down” vote (negative); or as a control, no vote at all.The team then observed how users rated thosecomments. The users generated more than(50) 100,000 comments that were viewed more than10 million times and rated more than 300,000 timesby other users.At least when it comes to comments on newssites, the crowd is more herdlike than wise.(55) Comments that received fake positive votes from theresearchers were 32% more likely to receive morepositive votes compared with a control, the teamreports. And those comments were no more likelythan the control to be down-voted by the next viewer(60) to see them. By the end of the study, positivelymanipulated comments got an overall boost of about25%. However, the same did not hold true for negativemanipulation. The ratings of comments thatgot a fake down vote were usually negated by an up(65) vote by the next user to see them.“Our experiment does not reveal the psychologybehind people’s decisions,” Aral says, “but anintuitive explanation is that people are moreskeptical of negative social influence. They’re more(70) willing to go along with positive opinions from otherpeople.”Duncan Watts, a network scientist at MicrosoftResearch in New York City, agrees with thatconclusion. “[But] one question is whether the(75) positive [herding] bias is specific to this site” or truein general, Watts says. He points out that thecategory of the news items in the experiment had astrong effect on how much people could bemanipulated. “I would have thought that ‘business’ is(80) pretty similar to ‘economics,’ yet they find a muchstronger effect (almost 50% stronger) for the formerthan the latter. What explains this difference? If we’regoing to apply these findings in the real world, we’llneed to know the answers.”(85) Will companies be able to boost their products bymanipulating online ratings on a massive scale?“That is easier said than done,” Watts says. If peopledetect—or learn—that comments on a website arebeing manipulated, the herd may spook and leave(90) entirely.Mean score: mean of scores for the comments in each category, with the score for each comment being determined by the number of positive votes from website users minus the number of negative votesAdapted from Lev Muchnik, Sinan Aral, and Sean J. Taylor, “Social Influence Bias: A Randomized Experiment.” ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.Q.Which choice best supports the view of the “skeptics” (line 20)?a)Lines 55-58 (“Comments... reports”)b)Lines 58-60 (“And... them”)c)Lines 63-65 (“The ratings... them”)d)Lines 76-79 (“He... manipulated”)Correct answer is option 'A'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for SAT 2025 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from John Bohannon, "Why You Shouldnt Trust Internet Comments." ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.The “wisdom of crowds” has become a mantra ofthe Internet age. Need to choose a new vacuumcleaner? Check out the reviews on online merchantAmazon. But a new study suggests that such online(5) scores don’t always reveal the best choice. A massivecontrolled experiment of Web users finds that suchratings are highly susceptible to irrational “herdbehavior”—and that the herd can be manipulated.Sometimes the crowd really is wiser than you. The(10) classic examples are guessing the weight of a bull orthe number of gumballs in a jar. Your guess isprobably going to be far from the mark, whereas theaverage of many people’s choices is remarkably closeto the true number.(15) But what happens when the goal is to judgesomething less tangible, such as the quality or worthof a product? According to one theory, the wisdomof the crowd still holds—measuring the aggregate ofpeople’s opinions produces a stable, reliable(20) value. Skeptics, however, argue that people’sopinions are easily swayed by those of others. Sonudging a crowd early on by presenting contraryopinions—for example, exposing them to some verygood or very bad attitudes—will steer the crowd in a(25) different direction. To test which hypothesis is true,you would need to manipulate huge numbers ofpeople, exposing them to false information anddetermining how it affects their opinions.A team led by Sinan Aral, a network scientist at(30) the Massachusetts Institute of Technology inCambridge, did exactly that. Aral has been secretlyworking with a popular website that aggregates newsstories. The website allows users to make commentsabout news stories and vote each other’s comments(35) up or down. The vote tallies are visible as a numbernext to each comment, and the position of thecomments is chronological. (Stories on the site get anaverage of about ten comments and about three votesper comment.) It’s a follow-up to his experiment(40) using people’s ratings of movies to measure howmuch individual people influence each other online(answer: a lot). This time, he wanted to know howmuch the crowd influences the individual, andwhether it can be controlled from outside.(45) For five months, every comment submitted by auser randomly received an “up” vote (positive); a“down” vote (negative); or as a control, no vote at all.The team then observed how users rated thosecomments. The users generated more than(50) 100,000 comments that were viewed more than10 million times and rated more than 300,000 timesby other users.At least when it comes to comments on newssites, the crowd is more herdlike than wise.(55) Comments that received fake positive votes from theresearchers were 32% more likely to receive morepositive votes compared with a control, the teamreports. And those comments were no more likelythan the control to be down-voted by the next viewer(60) to see them. By the end of the study, positivelymanipulated comments got an overall boost of about25%. However, the same did not hold true for negativemanipulation. The ratings of comments thatgot a fake down vote were usually negated by an up(65) vote by the next user to see them.“Our experiment does not reveal the psychologybehind people’s decisions,” Aral says, “but anintuitive explanation is that people are moreskeptical of negative social influence. They’re more(70) willing to go along with positive opinions from otherpeople.”Duncan Watts, a network scientist at MicrosoftResearch in New York City, agrees with thatconclusion. “[But] one question is whether the(75) positive [herding] bias is specific to this site” or truein general, Watts says. He points out that thecategory of the news items in the experiment had astrong effect on how much people could bemanipulated. “I would have thought that ‘business’ is(80) pretty similar to ‘economics,’ yet they find a muchstronger effect (almost 50% stronger) for the formerthan the latter. What explains this difference? If we’regoing to apply these findings in the real world, we’llneed to know the answers.”(85) Will companies be able to boost their products bymanipulating online ratings on a massive scale?“That is easier said than done,” Watts says. If peopledetect—or learn—that comments on a website arebeing manipulated, the herd may spook and leave(90) entirely.Mean score: mean of scores for the comments in each category, with the score for each comment being determined by the number of positive votes from website users minus the number of negative votesAdapted from Lev Muchnik, Sinan Aral, and Sean J. Taylor, “Social Influence Bias: A Randomized Experiment.” ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.Q.Which choice best supports the view of the “skeptics” (line 20)?a)Lines 55-58 (“Comments... reports”)b)Lines 58-60 (“And... them”)c)Lines 63-65 (“The ratings... them”)d)Lines 76-79 (“He... manipulated”)Correct answer is option 'A'. Can you explain this answer?.

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from John Bohannon, "Why You Shouldnt Trust Internet Comments." ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.The “wisdom of crowds” has become a mantra ofthe Internet age. Need to choose a new vacuumcleaner? Check out the reviews on online merchantAmazon. But a new study suggests that such online(5) scores don’t always reveal the best choice. A massivecontrolled experiment of Web users finds that suchratings are highly susceptible to irrational “herdbehavior”—and that the herd can be manipulated.Sometimes the crowd really is wiser than you. The(10) classic examples are guessing the weight of a bull orthe number of gumballs in a jar. Your guess isprobably going to be far from the mark, whereas theaverage of many people’s choices is remarkably closeto the true number.(15) But what happens when the goal is to judgesomething less tangible, such as the quality or worthof a product? According to one theory, the wisdomof the crowd still holds—measuring the aggregate ofpeople’s opinions produces a stable, reliable(20) value. Skeptics, however, argue that people’sopinions are easily swayed by those of others. Sonudging a crowd early on by presenting contraryopinions—for example, exposing them to some verygood or very bad attitudes—will steer the crowd in a(25) different direction. To test which hypothesis is true,you would need to manipulate huge numbers ofpeople, exposing them to false information anddetermining how it affects their opinions.A team led by Sinan Aral, a network scientist at(30) the Massachusetts Institute of Technology inCambridge, did exactly that. Aral has been secretlyworking with a popular website that aggregates newsstories. The website allows users to make commentsabout news stories and vote each other’s comments(35) up or down. The vote tallies are visible as a numbernext to each comment, and the position of thecomments is chronological. (Stories on the site get anaverage of about ten comments and about three votesper comment.) It’s a follow-up to his experiment(40) using people’s ratings of movies to measure howmuch individual people influence each other online(answer: a lot). This time, he wanted to know howmuch the crowd influences the individual, andwhether it can be controlled from outside.(45) For five months, every comment submitted by auser randomly received an “up” vote (positive); a“down” vote (negative); or as a control, no vote at all.The team then observed how users rated thosecomments. The users generated more than(50) 100,000 comments that were viewed more than10 million times and rated more than 300,000 timesby other users.At least when it comes to comments on newssites, the crowd is more herdlike than wise.(55) Comments that received fake positive votes from theresearchers were 32% more likely to receive morepositive votes compared with a control, the teamreports. And those comments were no more likelythan the control to be down-voted by the next viewer(60) to see them. By the end of the study, positivelymanipulated comments got an overall boost of about25%. However, the same did not hold true for negativemanipulation. The ratings of comments thatgot a fake down vote were usually negated by an up(65) vote by the next user to see them.“Our experiment does not reveal the psychologybehind people’s decisions,” Aral says, “but anintuitive explanation is that people are moreskeptical of negative social influence. They’re more(70) willing to go along with positive opinions from otherpeople.”Duncan Watts, a network scientist at MicrosoftResearch in New York City, agrees with thatconclusion. “[But] one question is whether the(75) positive [herding] bias is specific to this site” or truein general, Watts says. He points out that thecategory of the news items in the experiment had astrong effect on how much people could bemanipulated. “I would have thought that ‘business’ is(80) pretty similar to ‘economics,’ yet they find a muchstronger effect (almost 50% stronger) for the formerthan the latter. What explains this difference? If we’regoing to apply these findings in the real world, we’llneed to know the answers.”(85) Will companies be able to boost their products bymanipulating online ratings on a massive scale?“That is easier said than done,” Watts says. If peopledetect—or learn—that comments on a website arebeing manipulated, the herd may spook and leave(90) entirely.Mean score: mean of scores for the comments in each category, with the score for each comment being determined by the number of positive votes from website users minus the number of negative votesAdapted from Lev Muchnik, Sinan Aral, and Sean J. Taylor, “Social Influence Bias: A Randomized Experiment.” ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.Q.Which choice best supports the view of the “skeptics” (line 20)?a)Lines 55-58 (“Comments... reports”)b)Lines 58-60 (“And... them”)c)Lines 63-65 (“The ratings... them”)d)Lines 76-79 (“He... manipulated”)Correct answer is option 'A'. Can you explain this answer? for SAT 2025 is part of SAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the SAT exam syllabus. Information about Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from John Bohannon, "Why You Shouldnt Trust Internet Comments." ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.The “wisdom of crowds” has become a mantra ofthe Internet age. Need to choose a new vacuumcleaner? Check out the reviews on online merchantAmazon. But a new study suggests that such online(5) scores don’t always reveal the best choice. A massivecontrolled experiment of Web users finds that suchratings are highly susceptible to irrational “herdbehavior”—and that the herd can be manipulated.Sometimes the crowd really is wiser than you. The(10) classic examples are guessing the weight of a bull orthe number of gumballs in a jar. Your guess isprobably going to be far from the mark, whereas theaverage of many people’s choices is remarkably closeto the true number.(15) But what happens when the goal is to judgesomething less tangible, such as the quality or worthof a product? According to one theory, the wisdomof the crowd still holds—measuring the aggregate ofpeople’s opinions produces a stable, reliable(20) value. Skeptics, however, argue that people’sopinions are easily swayed by those of others. Sonudging a crowd early on by presenting contraryopinions—for example, exposing them to some verygood or very bad attitudes—will steer the crowd in a(25) different direction. To test which hypothesis is true,you would need to manipulate huge numbers ofpeople, exposing them to false information anddetermining how it affects their opinions.A team led by Sinan Aral, a network scientist at(30) the Massachusetts Institute of Technology inCambridge, did exactly that. Aral has been secretlyworking with a popular website that aggregates newsstories. The website allows users to make commentsabout news stories and vote each other’s comments(35) up or down. The vote tallies are visible as a numbernext to each comment, and the position of thecomments is chronological. (Stories on the site get anaverage of about ten comments and about three votesper comment.) It’s a follow-up to his experiment(40) using people’s ratings of movies to measure howmuch individual people influence each other online(answer: a lot). This time, he wanted to know howmuch the crowd influences the individual, andwhether it can be controlled from outside.(45) For five months, every comment submitted by auser randomly received an “up” vote (positive); a“down” vote (negative); or as a control, no vote at all.The team then observed how users rated thosecomments. The users generated more than(50) 100,000 comments that were viewed more than10 million times and rated more than 300,000 timesby other users.At least when it comes to comments on newssites, the crowd is more herdlike than wise.(55) Comments that received fake positive votes from theresearchers were 32% more likely to receive morepositive votes compared with a control, the teamreports. And those comments were no more likelythan the control to be down-voted by the next viewer(60) to see them. By the end of the study, positivelymanipulated comments got an overall boost of about25%. However, the same did not hold true for negativemanipulation. The ratings of comments thatgot a fake down vote were usually negated by an up(65) vote by the next user to see them.“Our experiment does not reveal the psychologybehind people’s decisions,” Aral says, “but anintuitive explanation is that people are moreskeptical of negative social influence. They’re more(70) willing to go along with positive opinions from otherpeople.”Duncan Watts, a network scientist at MicrosoftResearch in New York City, agrees with thatconclusion. “[But] one question is whether the(75) positive [herding] bias is specific to this site” or truein general, Watts says. He points out that thecategory of the news items in the experiment had astrong effect on how much people could bemanipulated. “I would have thought that ‘business’ is(80) pretty similar to ‘economics,’ yet they find a muchstronger effect (almost 50% stronger) for the formerthan the latter. What explains this difference? If we’regoing to apply these findings in the real world, we’llneed to know the answers.”(85) Will companies be able to boost their products bymanipulating online ratings on a massive scale?“That is easier said than done,” Watts says. If peopledetect—or learn—that comments on a website arebeing manipulated, the herd may spook and leave(90) entirely.Mean score: mean of scores for the comments in each category, with the score for each comment being determined by the number of positive votes from website users minus the number of negative votesAdapted from Lev Muchnik, Sinan Aral, and Sean J. Taylor, “Social Influence Bias: A Randomized Experiment.” ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.Q.Which choice best supports the view of the “skeptics” (line 20)?a)Lines 55-58 (“Comments... reports”)b)Lines 58-60 (“And... them”)c)Lines 63-65 (“The ratings... them”)d)Lines 76-79 (“He... manipulated”)Correct answer is option 'A'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for SAT 2025 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from John Bohannon, "Why You Shouldnt Trust Internet Comments." ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.The “wisdom of crowds” has become a mantra ofthe Internet age. Need to choose a new vacuumcleaner? Check out the reviews on online merchantAmazon. But a new study suggests that such online(5) scores don’t always reveal the best choice. A massivecontrolled experiment of Web users finds that suchratings are highly susceptible to irrational “herdbehavior”—and that the herd can be manipulated.Sometimes the crowd really is wiser than you. The(10) classic examples are guessing the weight of a bull orthe number of gumballs in a jar. Your guess isprobably going to be far from the mark, whereas theaverage of many people’s choices is remarkably closeto the true number.(15) But what happens when the goal is to judgesomething less tangible, such as the quality or worthof a product? According to one theory, the wisdomof the crowd still holds—measuring the aggregate ofpeople’s opinions produces a stable, reliable(20) value. Skeptics, however, argue that people’sopinions are easily swayed by those of others. Sonudging a crowd early on by presenting contraryopinions—for example, exposing them to some verygood or very bad attitudes—will steer the crowd in a(25) different direction. To test which hypothesis is true,you would need to manipulate huge numbers ofpeople, exposing them to false information anddetermining how it affects their opinions.A team led by Sinan Aral, a network scientist at(30) the Massachusetts Institute of Technology inCambridge, did exactly that. Aral has been secretlyworking with a popular website that aggregates newsstories. The website allows users to make commentsabout news stories and vote each other’s comments(35) up or down. The vote tallies are visible as a numbernext to each comment, and the position of thecomments is chronological. (Stories on the site get anaverage of about ten comments and about three votesper comment.) It’s a follow-up to his experiment(40) using people’s ratings of movies to measure howmuch individual people influence each other online(answer: a lot). This time, he wanted to know howmuch the crowd influences the individual, andwhether it can be controlled from outside.(45) For five months, every comment submitted by auser randomly received an “up” vote (positive); a“down” vote (negative); or as a control, no vote at all.The team then observed how users rated thosecomments. The users generated more than(50) 100,000 comments that were viewed more than10 million times and rated more than 300,000 timesby other users.At least when it comes to comments on newssites, the crowd is more herdlike than wise.(55) Comments that received fake positive votes from theresearchers were 32% more likely to receive morepositive votes compared with a control, the teamreports. And those comments were no more likelythan the control to be down-voted by the next viewer(60) to see them. By the end of the study, positivelymanipulated comments got an overall boost of about25%. However, the same did not hold true for negativemanipulation. The ratings of comments thatgot a fake down vote were usually negated by an up(65) vote by the next user to see them.“Our experiment does not reveal the psychologybehind people’s decisions,” Aral says, “but anintuitive explanation is that people are moreskeptical of negative social influence. They’re more(70) willing to go along with positive opinions from otherpeople.”Duncan Watts, a network scientist at MicrosoftResearch in New York City, agrees with thatconclusion. “[But] one question is whether the(75) positive [herding] bias is specific to this site” or truein general, Watts says. He points out that thecategory of the news items in the experiment had astrong effect on how much people could bemanipulated. “I would have thought that ‘business’ is(80) pretty similar to ‘economics,’ yet they find a muchstronger effect (almost 50% stronger) for the formerthan the latter. What explains this difference? If we’regoing to apply these findings in the real world, we’llneed to know the answers.”(85) Will companies be able to boost their products bymanipulating online ratings on a massive scale?“That is easier said than done,” Watts says. If peopledetect—or learn—that comments on a website arebeing manipulated, the herd may spook and leave(90) entirely.Mean score: mean of scores for the comments in each category, with the score for each comment being determined by the number of positive votes from website users minus the number of negative votesAdapted from Lev Muchnik, Sinan Aral, and Sean J. Taylor, “Social Influence Bias: A Randomized Experiment.” ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.Q.Which choice best supports the view of the “skeptics” (line 20)?a)Lines 55-58 (“Comments... reports”)b)Lines 58-60 (“And... them”)c)Lines 63-65 (“The ratings... them”)d)Lines 76-79 (“He... manipulated”)Correct answer is option 'A'. Can you explain this answer?.

Solutions for Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from John Bohannon, "Why You Shouldnt Trust Internet Comments." ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.The “wisdom of crowds” has become a mantra ofthe Internet age. Need to choose a new vacuumcleaner? Check out the reviews on online merchantAmazon. But a new study suggests that such online(5) scores don’t always reveal the best choice. A massivecontrolled experiment of Web users finds that suchratings are highly susceptible to irrational “herdbehavior”—and that the herd can be manipulated.Sometimes the crowd really is wiser than you. The(10) classic examples are guessing the weight of a bull orthe number of gumballs in a jar. Your guess isprobably going to be far from the mark, whereas theaverage of many people’s choices is remarkably closeto the true number.(15) But what happens when the goal is to judgesomething less tangible, such as the quality or worthof a product? According to one theory, the wisdomof the crowd still holds—measuring the aggregate ofpeople’s opinions produces a stable, reliable(20) value. Skeptics, however, argue that people’sopinions are easily swayed by those of others. Sonudging a crowd early on by presenting contraryopinions—for example, exposing them to some verygood or very bad attitudes—will steer the crowd in a(25) different direction. To test which hypothesis is true,you would need to manipulate huge numbers ofpeople, exposing them to false information anddetermining how it affects their opinions.A team led by Sinan Aral, a network scientist at(30) the Massachusetts Institute of Technology inCambridge, did exactly that. Aral has been secretlyworking with a popular website that aggregates newsstories. The website allows users to make commentsabout news stories and vote each other’s comments(35) up or down. The vote tallies are visible as a numbernext to each comment, and the position of thecomments is chronological. (Stories on the site get anaverage of about ten comments and about three votesper comment.) It’s a follow-up to his experiment(40) using people’s ratings of movies to measure howmuch individual people influence each other online(answer: a lot). This time, he wanted to know howmuch the crowd influences the individual, andwhether it can be controlled from outside.(45) For five months, every comment submitted by auser randomly received an “up” vote (positive); a“down” vote (negative); or as a control, no vote at all.The team then observed how users rated thosecomments. The users generated more than(50) 100,000 comments that were viewed more than10 million times and rated more than 300,000 timesby other users.At least when it comes to comments on newssites, the crowd is more herdlike than wise.(55) Comments that received fake positive votes from theresearchers were 32% more likely to receive morepositive votes compared with a control, the teamreports. And those comments were no more likelythan the control to be down-voted by the next viewer(60) to see them. By the end of the study, positivelymanipulated comments got an overall boost of about25%. However, the same did not hold true for negativemanipulation. The ratings of comments thatgot a fake down vote were usually negated by an up(65) vote by the next user to see them.“Our experiment does not reveal the psychologybehind people’s decisions,” Aral says, “but anintuitive explanation is that people are moreskeptical of negative social influence. They’re more(70) willing to go along with positive opinions from otherpeople.”Duncan Watts, a network scientist at MicrosoftResearch in New York City, agrees with thatconclusion. “[But] one question is whether the(75) positive [herding] bias is specific to this site” or truein general, Watts says. He points out that thecategory of the news items in the experiment had astrong effect on how much people could bemanipulated. “I would have thought that ‘business’ is(80) pretty similar to ‘economics,’ yet they find a muchstronger effect (almost 50% stronger) for the formerthan the latter. What explains this difference? If we’regoing to apply these findings in the real world, we’llneed to know the answers.”(85) Will companies be able to boost their products bymanipulating online ratings on a massive scale?“That is easier said than done,” Watts says. If peopledetect—or learn—that comments on a website arebeing manipulated, the herd may spook and leave(90) entirely.Mean score: mean of scores for the comments in each category, with the score for each comment being determined by the number of positive votes from website users minus the number of negative votesAdapted from Lev Muchnik, Sinan Aral, and Sean J. Taylor, “Social Influence Bias: A Randomized Experiment.” ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.Q.Which choice best supports the view of the “skeptics” (line 20)?a)Lines 55-58 (“Comments... reports”)b)Lines 58-60 (“And... them”)c)Lines 63-65 (“The ratings... them”)d)Lines 76-79 (“He... manipulated”)Correct answer is option 'A'. Can you explain this answer? in English & in Hindi are available as part of our courses for SAT.

Download more important topics, notes, lectures and mock test series for SAT Exam by signing up for free.

Here you can find the meaning of Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from John Bohannon, "Why You Shouldnt Trust Internet Comments." ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.The “wisdom of crowds” has become a mantra ofthe Internet age. Need to choose a new vacuumcleaner? Check out the reviews on online merchantAmazon. But a new study suggests that such online(5) scores don’t always reveal the best choice. A massivecontrolled experiment of Web users finds that suchratings are highly susceptible to irrational “herdbehavior”—and that the herd can be manipulated.Sometimes the crowd really is wiser than you. The(10) classic examples are guessing the weight of a bull orthe number of gumballs in a jar. Your guess isprobably going to be far from the mark, whereas theaverage of many people’s choices is remarkably closeto the true number.(15) But what happens when the goal is to judgesomething less tangible, such as the quality or worthof a product? According to one theory, the wisdomof the crowd still holds—measuring the aggregate ofpeople’s opinions produces a stable, reliable(20) value. Skeptics, however, argue that people’sopinions are easily swayed by those of others. Sonudging a crowd early on by presenting contraryopinions—for example, exposing them to some verygood or very bad attitudes—will steer the crowd in a(25) different direction. To test which hypothesis is true,you would need to manipulate huge numbers ofpeople, exposing them to false information anddetermining how it affects their opinions.A team led by Sinan Aral, a network scientist at(30) the Massachusetts Institute of Technology inCambridge, did exactly that. Aral has been secretlyworking with a popular website that aggregates newsstories. The website allows users to make commentsabout news stories and vote each other’s comments(35) up or down. The vote tallies are visible as a numbernext to each comment, and the position of thecomments is chronological. (Stories on the site get anaverage of about ten comments and about three votesper comment.) It’s a follow-up to his experiment(40) using people’s ratings of movies to measure howmuch individual people influence each other online(answer: a lot). This time, he wanted to know howmuch the crowd influences the individual, andwhether it can be controlled from outside.(45) For five months, every comment submitted by auser randomly received an “up” vote (positive); a“down” vote (negative); or as a control, no vote at all.The team then observed how users rated thosecomments. The users generated more than(50) 100,000 comments that were viewed more than10 million times and rated more than 300,000 timesby other users.At least when it comes to comments on newssites, the crowd is more herdlike than wise.(55) Comments that received fake positive votes from theresearchers were 32% more likely to receive morepositive votes compared with a control, the teamreports. And those comments were no more likelythan the control to be down-voted by the next viewer(60) to see them. By the end of the study, positivelymanipulated comments got an overall boost of about25%. However, the same did not hold true for negativemanipulation. The ratings of comments thatgot a fake down vote were usually negated by an up(65) vote by the next user to see them.“Our experiment does not reveal the psychologybehind people’s decisions,” Aral says, “but anintuitive explanation is that people are moreskeptical of negative social influence. They’re more(70) willing to go along with positive opinions from otherpeople.”Duncan Watts, a network scientist at MicrosoftResearch in New York City, agrees with thatconclusion. “[But] one question is whether the(75) positive [herding] bias is specific to this site” or truein general, Watts says. He points out that thecategory of the news items in the experiment had astrong effect on how much people could bemanipulated. “I would have thought that ‘business’ is(80) pretty similar to ‘economics,’ yet they find a muchstronger effect (almost 50% stronger) for the formerthan the latter. What explains this difference? If we’regoing to apply these findings in the real world, we’llneed to know the answers.”(85) Will companies be able to boost their products bymanipulating online ratings on a massive scale?“That is easier said than done,” Watts says. If peopledetect—or learn—that comments on a website arebeing manipulated, the herd may spook and leave(90) entirely.Mean score: mean of scores for the comments in each category, with the score for each comment being determined by the number of positive votes from website users minus the number of negative votesAdapted from Lev Muchnik, Sinan Aral, and Sean J. Taylor, “Social Influence Bias: A Randomized Experiment.” ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.Q.Which choice best supports the view of the “skeptics” (line 20)?a)Lines 55-58 (“Comments... reports”)b)Lines 58-60 (“And... them”)c)Lines 63-65 (“The ratings... them”)d)Lines 76-79 (“He... manipulated”)Correct answer is option 'A'. Can you explain this answer? defined & explained in the simplest way possible. Besides giving the explanation of

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from John Bohannon, "Why You Shouldnt Trust Internet Comments." ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.The “wisdom of crowds” has become a mantra ofthe Internet age. Need to choose a new vacuumcleaner? Check out the reviews on online merchantAmazon. But a new study suggests that such online(5) scores don’t always reveal the best choice. A massivecontrolled experiment of Web users finds that suchratings are highly susceptible to irrational “herdbehavior”—and that the herd can be manipulated.Sometimes the crowd really is wiser than you. The(10) classic examples are guessing the weight of a bull orthe number of gumballs in a jar. Your guess isprobably going to be far from the mark, whereas theaverage of many people’s choices is remarkably closeto the true number.(15) But what happens when the goal is to judgesomething less tangible, such as the quality or worthof a product? According to one theory, the wisdomof the crowd still holds—measuring the aggregate ofpeople’s opinions produces a stable, reliable(20) value. Skeptics, however, argue that people’sopinions are easily swayed by those of others. Sonudging a crowd early on by presenting contraryopinions—for example, exposing them to some verygood or very bad attitudes—will steer the crowd in a(25) different direction. To test which hypothesis is true,you would need to manipulate huge numbers ofpeople, exposing them to false information anddetermining how it affects their opinions.A team led by Sinan Aral, a network scientist at(30) the Massachusetts Institute of Technology inCambridge, did exactly that. Aral has been secretlyworking with a popular website that aggregates newsstories. The website allows users to make commentsabout news stories and vote each other’s comments(35) up or down. The vote tallies are visible as a numbernext to each comment, and the position of thecomments is chronological. (Stories on the site get anaverage of about ten comments and about three votesper comment.) It’s a follow-up to his experiment(40) using people’s ratings of movies to measure howmuch individual people influence each other online(answer: a lot). This time, he wanted to know howmuch the crowd influences the individual, andwhether it can be controlled from outside.(45) For five months, every comment submitted by auser randomly received an “up” vote (positive); a“down” vote (negative); or as a control, no vote at all.The team then observed how users rated thosecomments. The users generated more than(50) 100,000 comments that were viewed more than10 million times and rated more than 300,000 timesby other users.At least when it comes to comments on newssites, the crowd is more herdlike than wise.(55) Comments that received fake positive votes from theresearchers were 32% more likely to receive morepositive votes compared with a control, the teamreports. And those comments were no more likelythan the control to be down-voted by the next viewer(60) to see them. By the end of the study, positivelymanipulated comments got an overall boost of about25%. However, the same did not hold true for negativemanipulation. The ratings of comments thatgot a fake down vote were usually negated by an up(65) vote by the next user to see them.“Our experiment does not reveal the psychologybehind people’s decisions,” Aral says, “but anintuitive explanation is that people are moreskeptical of negative social influence. They’re more(70) willing to go along with positive opinions from otherpeople.”Duncan Watts, a network scientist at MicrosoftResearch in New York City, agrees with thatconclusion. “[But] one question is whether the(75) positive [herding] bias is specific to this site” or truein general, Watts says. He points out that thecategory of the news items in the experiment had astrong effect on how much people could bemanipulated. “I would have thought that ‘business’ is(80) pretty similar to ‘economics,’ yet they find a muchstronger effect (almost 50% stronger) for the formerthan the latter. What explains this difference? If we’regoing to apply these findings in the real world, we’llneed to know the answers.”(85) Will companies be able to boost their products bymanipulating online ratings on a massive scale?“That is easier said than done,” Watts says. If peopledetect—or learn—that comments on a website arebeing manipulated, the herd may spook and leave(90) entirely.Mean score: mean of scores for the comments in each category, with the score for each comment being determined by the number of positive votes from website users minus the number of negative votesAdapted from Lev Muchnik, Sinan Aral, and Sean J. Taylor, “Social Influence Bias: A Randomized Experiment.” ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.Q.Which choice best supports the view of the “skeptics” (line 20)?a)Lines 55-58 (“Comments... reports”)b)Lines 58-60 (“And... them”)c)Lines 63-65 (“The ratings... them”)d)Lines 76-79 (“He... manipulated”)Correct answer is option 'A'. Can you explain this answer?, a detailed solution for Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from John Bohannon, "Why You Shouldnt Trust Internet Comments." ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.The “wisdom of crowds” has become a mantra ofthe Internet age. Need to choose a new vacuumcleaner? Check out the reviews on online merchantAmazon. But a new study suggests that such online(5) scores don’t always reveal the best choice. A massivecontrolled experiment of Web users finds that suchratings are highly susceptible to irrational “herdbehavior”—and that the herd can be manipulated.Sometimes the crowd really is wiser than you. The(10) classic examples are guessing the weight of a bull orthe number of gumballs in a jar. Your guess isprobably going to be far from the mark, whereas theaverage of many people’s choices is remarkably closeto the true number.(15) But what happens when the goal is to judgesomething less tangible, such as the quality or worthof a product? According to one theory, the wisdomof the crowd still holds—measuring the aggregate ofpeople’s opinions produces a stable, reliable(20) value. Skeptics, however, argue that people’sopinions are easily swayed by those of others. Sonudging a crowd early on by presenting contraryopinions—for example, exposing them to some verygood or very bad attitudes—will steer the crowd in a(25) different direction. To test which hypothesis is true,you would need to manipulate huge numbers ofpeople, exposing them to false information anddetermining how it affects their opinions.A team led by Sinan Aral, a network scientist at(30) the Massachusetts Institute of Technology inCambridge, did exactly that. Aral has been secretlyworking with a popular website that aggregates newsstories. The website allows users to make commentsabout news stories and vote each other’s comments(35) up or down. The vote tallies are visible as a numbernext to each comment, and the position of thecomments is chronological. (Stories on the site get anaverage of about ten comments and about three votesper comment.) It’s a follow-up to his experiment(40) using people’s ratings of movies to measure howmuch individual people influence each other online(answer: a lot). This time, he wanted to know howmuch the crowd influences the individual, andwhether it can be controlled from outside.(45) For five months, every comment submitted by auser randomly received an “up” vote (positive); a“down” vote (negative); or as a control, no vote at all.The team then observed how users rated thosecomments. The users generated more than(50) 100,000 comments that were viewed more than10 million times and rated more than 300,000 timesby other users.At least when it comes to comments on newssites, the crowd is more herdlike than wise.(55) Comments that received fake positive votes from theresearchers were 32% more likely to receive morepositive votes compared with a control, the teamreports. And those comments were no more likelythan the control to be down-voted by the next viewer(60) to see them. By the end of the study, positivelymanipulated comments got an overall boost of about25%. However, the same did not hold true for negativemanipulation. The ratings of comments thatgot a fake down vote were usually negated by an up(65) vote by the next user to see them.“Our experiment does not reveal the psychologybehind people’s decisions,” Aral says, “but anintuitive explanation is that people are moreskeptical of negative social influence. They’re more(70) willing to go along with positive opinions from otherpeople.”Duncan Watts, a network scientist at MicrosoftResearch in New York City, agrees with thatconclusion. “[But] one question is whether the(75) positive [herding] bias is specific to this site” or truein general, Watts says. He points out that thecategory of the news items in the experiment had astrong effect on how much people could bemanipulated. “I would have thought that ‘business’ is(80) pretty similar to ‘economics,’ yet they find a muchstronger effect (almost 50% stronger) for the formerthan the latter. What explains this difference? If we’regoing to apply these findings in the real world, we’llneed to know the answers.”(85) Will companies be able to boost their products bymanipulating online ratings on a massive scale?“That is easier said than done,” Watts says. If peopledetect—or learn—that comments on a website arebeing manipulated, the herd may spook and leave(90) entirely.Mean score: mean of scores for the comments in each category, with the score for each comment being determined by the number of positive votes from website users minus the number of negative votesAdapted from Lev Muchnik, Sinan Aral, and Sean J. Taylor, “Social Influence Bias: A Randomized Experiment.” ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.Q.Which choice best supports the view of the “skeptics” (line 20)?a)Lines 55-58 (“Comments... reports”)b)Lines 58-60 (“And... them”)c)Lines 63-65 (“The ratings... them”)d)Lines 76-79 (“He... manipulated”)Correct answer is option 'A'. Can you explain this answer? has been provided alongside types of Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from John Bohannon, "Why You Shouldnt Trust Internet Comments." ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.The “wisdom of crowds” has become a mantra ofthe Internet age. Need to choose a new vacuumcleaner? Check out the reviews on online merchantAmazon. But a new study suggests that such online(5) scores don’t always reveal the best choice. A massivecontrolled experiment of Web users finds that suchratings are highly susceptible to irrational “herdbehavior”—and that the herd can be manipulated.Sometimes the crowd really is wiser than you. The(10) classic examples are guessing the weight of a bull orthe number of gumballs in a jar. Your guess isprobably going to be far from the mark, whereas theaverage of many people’s choices is remarkably closeto the true number.(15) But what happens when the goal is to judgesomething less tangible, such as the quality or worthof a product? According to one theory, the wisdomof the crowd still holds—measuring the aggregate ofpeople’s opinions produces a stable, reliable(20) value. Skeptics, however, argue that people’sopinions are easily swayed by those of others. Sonudging a crowd early on by presenting contraryopinions—for example, exposing them to some verygood or very bad attitudes—will steer the crowd in a(25) different direction. To test which hypothesis is true,you would need to manipulate huge numbers ofpeople, exposing them to false information anddetermining how it affects their opinions.A team led by Sinan Aral, a network scientist at(30) the Massachusetts Institute of Technology inCambridge, did exactly that. Aral has been secretlyworking with a popular website that aggregates newsstories. The website allows users to make commentsabout news stories and vote each other’s comments(35) up or down. The vote tallies are visible as a numbernext to each comment, and the position of thecomments is chronological. (Stories on the site get anaverage of about ten comments and about three votesper comment.) It’s a follow-up to his experiment(40) using people’s ratings of movies to measure howmuch individual people influence each other online(answer: a lot). This time, he wanted to know howmuch the crowd influences the individual, andwhether it can be controlled from outside.(45) For five months, every comment submitted by auser randomly received an “up” vote (positive); a“down” vote (negative); or as a control, no vote at all.The team then observed how users rated thosecomments. The users generated more than(50) 100,000 comments that were viewed more than10 million times and rated more than 300,000 timesby other users.At least when it comes to comments on newssites, the crowd is more herdlike than wise.(55) Comments that received fake positive votes from theresearchers were 32% more likely to receive morepositive votes compared with a control, the teamreports. And those comments were no more likelythan the control to be down-voted by the next viewer(60) to see them. By the end of the study, positivelymanipulated comments got an overall boost of about25%. However, the same did not hold true for negativemanipulation. The ratings of comments thatgot a fake down vote were usually negated by an up(65) vote by the next user to see them.“Our experiment does not reveal the psychologybehind people’s decisions,” Aral says, “but anintuitive explanation is that people are moreskeptical of negative social influence. They’re more(70) willing to go along with positive opinions from otherpeople.”Duncan Watts, a network scientist at MicrosoftResearch in New York City, agrees with thatconclusion. “[But] one question is whether the(75) positive [herding] bias is specific to this site” or truein general, Watts says. He points out that thecategory of the news items in the experiment had astrong effect on how much people could bemanipulated. “I would have thought that ‘business’ is(80) pretty similar to ‘economics,’ yet they find a muchstronger effect (almost 50% stronger) for the formerthan the latter. What explains this difference? If we’regoing to apply these findings in the real world, we’llneed to know the answers.”(85) Will companies be able to boost their products bymanipulating online ratings on a massive scale?“That is easier said than done,” Watts says. If peopledetect—or learn—that comments on a website arebeing manipulated, the herd may spook and leave(90) entirely.Mean score: mean of scores for the comments in each category, with the score for each comment being determined by the number of positive votes from website users minus the number of negative votesAdapted from Lev Muchnik, Sinan Aral, and Sean J. Taylor, “Social Influence Bias: A Randomized Experiment.” ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.Q.Which choice best supports the view of the “skeptics” (line 20)?a)Lines 55-58 (“Comments... reports”)b)Lines 58-60 (“And... them”)c)Lines 63-65 (“The ratings... them”)d)Lines 76-79 (“He... manipulated”)Correct answer is option 'A'. Can you explain this answer? theory, EduRev gives you an