SAT Exam > SAT Questions > Question based on the following passage and s...

Start Learning for Free

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “America's Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.

Experts often suggest that crime resembles

an epidemic. But what kind? Economics

professor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumb

for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along

(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause is

information. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travels

along major transportation routes, the cause is

microbial. Think influenza. If it spreads out like

a fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But

(10) if it's everywhere, all at once—as both the rise of

crime in the '60s and '70s and the fall of crime in

the '90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.

A molecule? That sounds crazy. What

molecule could be responsible for a steep and

(15) sudden decline in violent crime?

Well, here's one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.

In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultant

working for the US Department of Housing and

Urban Development on the costs and benefits of

(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growing

body of research had linked lead exposure in

small children with a whole raft of complications

later in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,

behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.

(25) A recent study had also suggested a link

between childhood lead exposure and juvenile

delinquency later on. Maybe reducing lead

exposure had an effect on violent crime too?

That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The

(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turns

out, wasn't paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chart

the rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused by

the rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,

you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from

(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early '40s through

the early '70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.

Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leaded

gasoline, emissions plummeted.

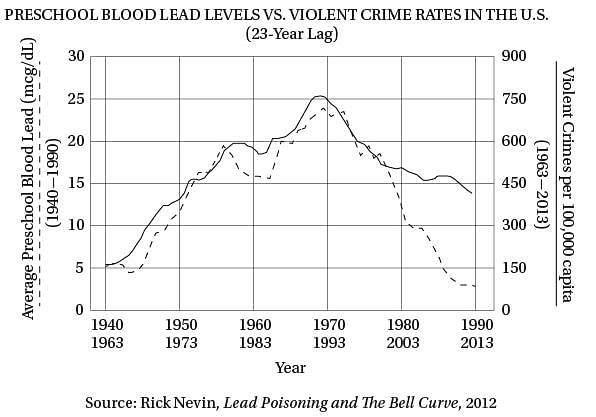

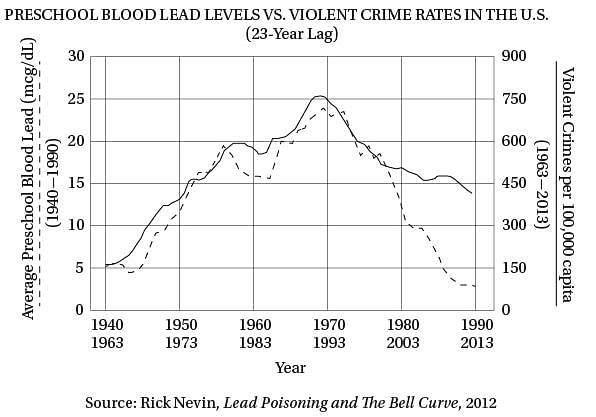

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the

(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). The

only thing different was the time period. Crime

rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the

'80s, and then began dropping steadily starting

in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily

(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

So Nevin dug up detailed data on lead

emissions and crime rates to see if the similarity

of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned

out to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded

(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, lead

emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of

the variation in violent crime in America. Toddlers

who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and

'50s really were more likely to become violent

(55) criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetra-

ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented by

General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking

and pinging in high-performance engines. As

(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and drivers

in powerful new cars increasingly asked service

station attendants to “fill 'er up with ethyl,” they

were unwittingly creating a crime wave two

decades later.

(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and it

prompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.

Nevin's paper was almost completely ignored,

and in one sense it's easy to see why—Nevin is

an economist, not a criminologist, and his paper

(70) was published in Environmental Research, not a

journal with a big readership in the criminology

community. What's more, a single correlation

between two curves isn't all that impressive,

econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose

(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined in

the '80s and '90s. No matter how good the fit, if

you only have a single correlation it might just be

a coincidence. You need to do something more to

establish causality.

(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data and

crime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,

Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and West

Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other

astonishingly well.

(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explain

some things we might not have realized even

needed explaining. For example, murder rates

have always been higher in big cities than in

towns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,

(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a small

area, they also had high densities of atmospheric

lead during the postwar era. But as lead levels

in gasoline decreased, the differences between

big and small cities largely went away. And guess

(95) what? The difference in murder rates went away

too. Today, homicide rates are similar in cities

of all sizes. It may be that violent crime isn't an

inevitable consequence of being a big city after all.

*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.

This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “America's Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.

Experts often suggest that crime resembles

an epidemic. But what kind? Economics

professor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumb

for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along

(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause is

information. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travels

along major transportation routes, the cause is

microbial. Think influenza. If it spreads out like

a fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But

(10) if it's everywhere, all at once—as both the rise of

crime in the '60s and '70s and the fall of crime in

the '90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.

A molecule? That sounds crazy. What

molecule could be responsible for a steep and

(15) sudden decline in violent crime?

Well, here's one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.

In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultant

working for the US Department of Housing and

Urban Development on the costs and benefits of

(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growing

body of research had linked lead exposure in

small children with a whole raft of complications

later in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,

behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.

(25) A recent study had also suggested a link

between childhood lead exposure and juvenile

delinquency later on. Maybe reducing lead

exposure had an effect on violent crime too?

That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The

(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turns

out, wasn't paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chart

the rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused by

the rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,

you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from

(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early '40s through

the early '70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.

Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leaded

gasoline, emissions plummeted.

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the

(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). The

only thing different was the time period. Crime

rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the

'80s, and then began dropping steadily starting

in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily

(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

So Nevin dug up detailed data on lead

emissions and crime rates to see if the similarity

of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned

out to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded

(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, lead

emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of

the variation in violent crime in America. Toddlers

who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and

'50s really were more likely to become violent

(55) criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetra-

ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented by

General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking

and pinging in high-performance engines. As

(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and drivers

in powerful new cars increasingly asked service

station attendants to “fill 'er up with ethyl,” they

were unwittingly creating a crime wave two

decades later.

(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and it

prompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.

Nevin's paper was almost completely ignored,

and in one sense it's easy to see why—Nevin is

an economist, not a criminologist, and his paper

(70) was published in Environmental Research, not a

journal with a big readership in the criminology

community. What's more, a single correlation

between two curves isn't all that impressive,

econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose

(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined in

the '80s and '90s. No matter how good the fit, if

you only have a single correlation it might just be

a coincidence. You need to do something more to

establish causality.

(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data and

crime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,

Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and West

Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other

astonishingly well.

(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explain

some things we might not have realized even

needed explaining. For example, murder rates

have always been higher in big cities than in

towns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,

(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a small

area, they also had high densities of atmospheric

lead during the postwar era. But as lead levels

in gasoline decreased, the differences between

big and small cities largely went away. And guess

(95) what? The difference in murder rates went away

too. Today, homicide rates are similar in cities

of all sizes. It may be that violent crime isn't an

inevitable consequence of being a big city after all.

*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.

Q. In line 49, “even better” most nearly means

- a)less controversial.

- b)more correlative.

- c)easier to calculate.

- d)more aesthetically engaging.

Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?

Most Upvoted Answer

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Thi...

The phrase even better (line 49) refers to the finding mentioned in the previous sentence that the similarity of the curves was as good as it seemed, suggesting that the data showed an even stronger correlation than Nevin had hoped.

|

Explore Courses for SAT exam

|

|

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “Americas Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.Experts often suggest that crime resemblesan epidemic. But what kind? Economicsprofessor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumbfor categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause isinformation. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travelsalong major transportation routes, the cause ismicrobial. Think influenza. If it spreads out likea fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But(10) if its everywhere, all at once—as both the rise ofcrime in the 60s and 70s and the fall of crime inthe 90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.A molecule? That sounds crazy. Whatmolecule could be responsible for a steep and(15) sudden decline in violent crime?Well, heres one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultantworking for the US Department of Housing andUrban Development on the costs and benefits of(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growingbody of research had linked lead exposure insmall children with a whole raft of complicationslater in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.(25) A recent study had also suggested a linkbetween childhood lead exposure and juveniledelinquency later on. Maybe reducing leadexposure had an effect on violent crime too?That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turnsout, wasnt paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chartthe rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused bythe rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early 40s throughthe early 70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leadedgasoline, emissions plummeted.Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). Theonly thing different was the time period. Crimerates rose dramatically in the 60s through the80s, and then began dropping steadily startingin the early 90s. The two curves looked eerily(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.So Nevin dug up detailed data on leademissions and crime rates to see if the similarityof the curves was as good as it seemed. It turnedout to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, leademissions from automobiles explain 90 percent ofthe variation in violent crime in America. Toddlerswho ingested high levels of lead in the 40s and50s really were more likely to become violent(55) criminals in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.And with that we have our molecule: tetra-ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented byGeneral Motors in the 1920s to prevent knockingand pinging in high-performance engines. As(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and driversin powerful new cars increasingly asked servicestation attendants to “fill er up with ethyl,” theywere unwittingly creating a crime wave twodecades later.(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and itprompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.Nevins paper was almost completely ignored,and in one sense its easy to see why—Nevin isan economist, not a criminologist, and his paper(70) was published in Environmental Research, not ajournal with a big readership in the criminologycommunity. Whats more, a single correlationbetween two curves isnt all that impressive,econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined inthe 80s and 90s. No matter how good the fit, ifyou only have a single correlation it might just bea coincidence. You need to do something more toestablish causality.(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data andcrime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and WestGermany. Every time, the two curves fit each otherastonishingly well.(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explainsome things we might not have realized evenneeded explaining. For example, murder rateshave always been higher in big cities than intowns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a smallarea, they also had high densities of atmosphericlead during the postwar era. But as lead levelsin gasoline decreased, the differences betweenbig and small cities largely went away. And guess(95) what? The difference in murder rates went awaytoo. Today, homicide rates are similar in citiesof all sizes. It may be that violent crime isnt aninevitable consequence of being a big city after all.*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.Q.In line 49, “even better” most nearly meansa)less controversial.b)more correlative.c)easier to calculate.d)more aesthetically engaging.Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?

Question Description

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “Americas Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.Experts often suggest that crime resemblesan epidemic. But what kind? Economicsprofessor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumbfor categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause isinformation. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travelsalong major transportation routes, the cause ismicrobial. Think influenza. If it spreads out likea fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But(10) if its everywhere, all at once—as both the rise ofcrime in the 60s and 70s and the fall of crime inthe 90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.A molecule? That sounds crazy. Whatmolecule could be responsible for a steep and(15) sudden decline in violent crime?Well, heres one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultantworking for the US Department of Housing andUrban Development on the costs and benefits of(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growingbody of research had linked lead exposure insmall children with a whole raft of complicationslater in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.(25) A recent study had also suggested a linkbetween childhood lead exposure and juveniledelinquency later on. Maybe reducing leadexposure had an effect on violent crime too?That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turnsout, wasnt paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chartthe rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused bythe rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early 40s throughthe early 70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leadedgasoline, emissions plummeted.Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). Theonly thing different was the time period. Crimerates rose dramatically in the 60s through the80s, and then began dropping steadily startingin the early 90s. The two curves looked eerily(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.So Nevin dug up detailed data on leademissions and crime rates to see if the similarityof the curves was as good as it seemed. It turnedout to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, leademissions from automobiles explain 90 percent ofthe variation in violent crime in America. Toddlerswho ingested high levels of lead in the 40s and50s really were more likely to become violent(55) criminals in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.And with that we have our molecule: tetra-ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented byGeneral Motors in the 1920s to prevent knockingand pinging in high-performance engines. As(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and driversin powerful new cars increasingly asked servicestation attendants to “fill er up with ethyl,” theywere unwittingly creating a crime wave twodecades later.(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and itprompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.Nevins paper was almost completely ignored,and in one sense its easy to see why—Nevin isan economist, not a criminologist, and his paper(70) was published in Environmental Research, not ajournal with a big readership in the criminologycommunity. Whats more, a single correlationbetween two curves isnt all that impressive,econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined inthe 80s and 90s. No matter how good the fit, ifyou only have a single correlation it might just bea coincidence. You need to do something more toestablish causality.(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data andcrime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and WestGermany. Every time, the two curves fit each otherastonishingly well.(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explainsome things we might not have realized evenneeded explaining. For example, murder rateshave always been higher in big cities than intowns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a smallarea, they also had high densities of atmosphericlead during the postwar era. But as lead levelsin gasoline decreased, the differences betweenbig and small cities largely went away. And guess(95) what? The difference in murder rates went awaytoo. Today, homicide rates are similar in citiesof all sizes. It may be that violent crime isnt aninevitable consequence of being a big city after all.*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.Q.In line 49, “even better” most nearly meansa)less controversial.b)more correlative.c)easier to calculate.d)more aesthetically engaging.Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? for SAT 2025 is part of SAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the SAT exam syllabus. Information about Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “Americas Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.Experts often suggest that crime resemblesan epidemic. But what kind? Economicsprofessor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumbfor categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause isinformation. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travelsalong major transportation routes, the cause ismicrobial. Think influenza. If it spreads out likea fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But(10) if its everywhere, all at once—as both the rise ofcrime in the 60s and 70s and the fall of crime inthe 90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.A molecule? That sounds crazy. Whatmolecule could be responsible for a steep and(15) sudden decline in violent crime?Well, heres one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultantworking for the US Department of Housing andUrban Development on the costs and benefits of(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growingbody of research had linked lead exposure insmall children with a whole raft of complicationslater in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.(25) A recent study had also suggested a linkbetween childhood lead exposure and juveniledelinquency later on. Maybe reducing leadexposure had an effect on violent crime too?That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turnsout, wasnt paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chartthe rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused bythe rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early 40s throughthe early 70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leadedgasoline, emissions plummeted.Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). Theonly thing different was the time period. Crimerates rose dramatically in the 60s through the80s, and then began dropping steadily startingin the early 90s. The two curves looked eerily(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.So Nevin dug up detailed data on leademissions and crime rates to see if the similarityof the curves was as good as it seemed. It turnedout to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, leademissions from automobiles explain 90 percent ofthe variation in violent crime in America. Toddlerswho ingested high levels of lead in the 40s and50s really were more likely to become violent(55) criminals in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.And with that we have our molecule: tetra-ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented byGeneral Motors in the 1920s to prevent knockingand pinging in high-performance engines. As(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and driversin powerful new cars increasingly asked servicestation attendants to “fill er up with ethyl,” theywere unwittingly creating a crime wave twodecades later.(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and itprompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.Nevins paper was almost completely ignored,and in one sense its easy to see why—Nevin isan economist, not a criminologist, and his paper(70) was published in Environmental Research, not ajournal with a big readership in the criminologycommunity. Whats more, a single correlationbetween two curves isnt all that impressive,econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined inthe 80s and 90s. No matter how good the fit, ifyou only have a single correlation it might just bea coincidence. You need to do something more toestablish causality.(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data andcrime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and WestGermany. Every time, the two curves fit each otherastonishingly well.(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explainsome things we might not have realized evenneeded explaining. For example, murder rateshave always been higher in big cities than intowns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a smallarea, they also had high densities of atmosphericlead during the postwar era. But as lead levelsin gasoline decreased, the differences betweenbig and small cities largely went away. And guess(95) what? The difference in murder rates went awaytoo. Today, homicide rates are similar in citiesof all sizes. It may be that violent crime isnt aninevitable consequence of being a big city after all.*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.Q.In line 49, “even better” most nearly meansa)less controversial.b)more correlative.c)easier to calculate.d)more aesthetically engaging.Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for SAT 2025 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “Americas Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.Experts often suggest that crime resemblesan epidemic. But what kind? Economicsprofessor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumbfor categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause isinformation. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travelsalong major transportation routes, the cause ismicrobial. Think influenza. If it spreads out likea fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But(10) if its everywhere, all at once—as both the rise ofcrime in the 60s and 70s and the fall of crime inthe 90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.A molecule? That sounds crazy. Whatmolecule could be responsible for a steep and(15) sudden decline in violent crime?Well, heres one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultantworking for the US Department of Housing andUrban Development on the costs and benefits of(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growingbody of research had linked lead exposure insmall children with a whole raft of complicationslater in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.(25) A recent study had also suggested a linkbetween childhood lead exposure and juveniledelinquency later on. Maybe reducing leadexposure had an effect on violent crime too?That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turnsout, wasnt paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chartthe rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused bythe rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early 40s throughthe early 70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leadedgasoline, emissions plummeted.Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). Theonly thing different was the time period. Crimerates rose dramatically in the 60s through the80s, and then began dropping steadily startingin the early 90s. The two curves looked eerily(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.So Nevin dug up detailed data on leademissions and crime rates to see if the similarityof the curves was as good as it seemed. It turnedout to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, leademissions from automobiles explain 90 percent ofthe variation in violent crime in America. Toddlerswho ingested high levels of lead in the 40s and50s really were more likely to become violent(55) criminals in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.And with that we have our molecule: tetra-ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented byGeneral Motors in the 1920s to prevent knockingand pinging in high-performance engines. As(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and driversin powerful new cars increasingly asked servicestation attendants to “fill er up with ethyl,” theywere unwittingly creating a crime wave twodecades later.(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and itprompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.Nevins paper was almost completely ignored,and in one sense its easy to see why—Nevin isan economist, not a criminologist, and his paper(70) was published in Environmental Research, not ajournal with a big readership in the criminologycommunity. Whats more, a single correlationbetween two curves isnt all that impressive,econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined inthe 80s and 90s. No matter how good the fit, ifyou only have a single correlation it might just bea coincidence. You need to do something more toestablish causality.(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data andcrime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and WestGermany. Every time, the two curves fit each otherastonishingly well.(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explainsome things we might not have realized evenneeded explaining. For example, murder rateshave always been higher in big cities than intowns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a smallarea, they also had high densities of atmosphericlead during the postwar era. But as lead levelsin gasoline decreased, the differences betweenbig and small cities largely went away. And guess(95) what? The difference in murder rates went awaytoo. Today, homicide rates are similar in citiesof all sizes. It may be that violent crime isnt aninevitable consequence of being a big city after all.*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.Q.In line 49, “even better” most nearly meansa)less controversial.b)more correlative.c)easier to calculate.d)more aesthetically engaging.Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?.

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “Americas Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.Experts often suggest that crime resemblesan epidemic. But what kind? Economicsprofessor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumbfor categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause isinformation. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travelsalong major transportation routes, the cause ismicrobial. Think influenza. If it spreads out likea fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But(10) if its everywhere, all at once—as both the rise ofcrime in the 60s and 70s and the fall of crime inthe 90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.A molecule? That sounds crazy. Whatmolecule could be responsible for a steep and(15) sudden decline in violent crime?Well, heres one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultantworking for the US Department of Housing andUrban Development on the costs and benefits of(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growingbody of research had linked lead exposure insmall children with a whole raft of complicationslater in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.(25) A recent study had also suggested a linkbetween childhood lead exposure and juveniledelinquency later on. Maybe reducing leadexposure had an effect on violent crime too?That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turnsout, wasnt paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chartthe rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused bythe rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early 40s throughthe early 70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leadedgasoline, emissions plummeted.Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). Theonly thing different was the time period. Crimerates rose dramatically in the 60s through the80s, and then began dropping steadily startingin the early 90s. The two curves looked eerily(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.So Nevin dug up detailed data on leademissions and crime rates to see if the similarityof the curves was as good as it seemed. It turnedout to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, leademissions from automobiles explain 90 percent ofthe variation in violent crime in America. Toddlerswho ingested high levels of lead in the 40s and50s really were more likely to become violent(55) criminals in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.And with that we have our molecule: tetra-ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented byGeneral Motors in the 1920s to prevent knockingand pinging in high-performance engines. As(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and driversin powerful new cars increasingly asked servicestation attendants to “fill er up with ethyl,” theywere unwittingly creating a crime wave twodecades later.(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and itprompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.Nevins paper was almost completely ignored,and in one sense its easy to see why—Nevin isan economist, not a criminologist, and his paper(70) was published in Environmental Research, not ajournal with a big readership in the criminologycommunity. Whats more, a single correlationbetween two curves isnt all that impressive,econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined inthe 80s and 90s. No matter how good the fit, ifyou only have a single correlation it might just bea coincidence. You need to do something more toestablish causality.(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data andcrime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and WestGermany. Every time, the two curves fit each otherastonishingly well.(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explainsome things we might not have realized evenneeded explaining. For example, murder rateshave always been higher in big cities than intowns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a smallarea, they also had high densities of atmosphericlead during the postwar era. But as lead levelsin gasoline decreased, the differences betweenbig and small cities largely went away. And guess(95) what? The difference in murder rates went awaytoo. Today, homicide rates are similar in citiesof all sizes. It may be that violent crime isnt aninevitable consequence of being a big city after all.*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.Q.In line 49, “even better” most nearly meansa)less controversial.b)more correlative.c)easier to calculate.d)more aesthetically engaging.Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? for SAT 2025 is part of SAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the SAT exam syllabus. Information about Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “Americas Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.Experts often suggest that crime resemblesan epidemic. But what kind? Economicsprofessor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumbfor categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause isinformation. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travelsalong major transportation routes, the cause ismicrobial. Think influenza. If it spreads out likea fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But(10) if its everywhere, all at once—as both the rise ofcrime in the 60s and 70s and the fall of crime inthe 90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.A molecule? That sounds crazy. Whatmolecule could be responsible for a steep and(15) sudden decline in violent crime?Well, heres one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultantworking for the US Department of Housing andUrban Development on the costs and benefits of(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growingbody of research had linked lead exposure insmall children with a whole raft of complicationslater in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.(25) A recent study had also suggested a linkbetween childhood lead exposure and juveniledelinquency later on. Maybe reducing leadexposure had an effect on violent crime too?That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turnsout, wasnt paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chartthe rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused bythe rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early 40s throughthe early 70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leadedgasoline, emissions plummeted.Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). Theonly thing different was the time period. Crimerates rose dramatically in the 60s through the80s, and then began dropping steadily startingin the early 90s. The two curves looked eerily(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.So Nevin dug up detailed data on leademissions and crime rates to see if the similarityof the curves was as good as it seemed. It turnedout to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, leademissions from automobiles explain 90 percent ofthe variation in violent crime in America. Toddlerswho ingested high levels of lead in the 40s and50s really were more likely to become violent(55) criminals in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.And with that we have our molecule: tetra-ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented byGeneral Motors in the 1920s to prevent knockingand pinging in high-performance engines. As(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and driversin powerful new cars increasingly asked servicestation attendants to “fill er up with ethyl,” theywere unwittingly creating a crime wave twodecades later.(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and itprompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.Nevins paper was almost completely ignored,and in one sense its easy to see why—Nevin isan economist, not a criminologist, and his paper(70) was published in Environmental Research, not ajournal with a big readership in the criminologycommunity. Whats more, a single correlationbetween two curves isnt all that impressive,econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined inthe 80s and 90s. No matter how good the fit, ifyou only have a single correlation it might just bea coincidence. You need to do something more toestablish causality.(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data andcrime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and WestGermany. Every time, the two curves fit each otherastonishingly well.(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explainsome things we might not have realized evenneeded explaining. For example, murder rateshave always been higher in big cities than intowns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a smallarea, they also had high densities of atmosphericlead during the postwar era. But as lead levelsin gasoline decreased, the differences betweenbig and small cities largely went away. And guess(95) what? The difference in murder rates went awaytoo. Today, homicide rates are similar in citiesof all sizes. It may be that violent crime isnt aninevitable consequence of being a big city after all.*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.Q.In line 49, “even better” most nearly meansa)less controversial.b)more correlative.c)easier to calculate.d)more aesthetically engaging.Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for SAT 2025 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “Americas Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.Experts often suggest that crime resemblesan epidemic. But what kind? Economicsprofessor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumbfor categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause isinformation. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travelsalong major transportation routes, the cause ismicrobial. Think influenza. If it spreads out likea fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But(10) if its everywhere, all at once—as both the rise ofcrime in the 60s and 70s and the fall of crime inthe 90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.A molecule? That sounds crazy. Whatmolecule could be responsible for a steep and(15) sudden decline in violent crime?Well, heres one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultantworking for the US Department of Housing andUrban Development on the costs and benefits of(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growingbody of research had linked lead exposure insmall children with a whole raft of complicationslater in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.(25) A recent study had also suggested a linkbetween childhood lead exposure and juveniledelinquency later on. Maybe reducing leadexposure had an effect on violent crime too?That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turnsout, wasnt paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chartthe rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused bythe rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early 40s throughthe early 70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leadedgasoline, emissions plummeted.Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). Theonly thing different was the time period. Crimerates rose dramatically in the 60s through the80s, and then began dropping steadily startingin the early 90s. The two curves looked eerily(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.So Nevin dug up detailed data on leademissions and crime rates to see if the similarityof the curves was as good as it seemed. It turnedout to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, leademissions from automobiles explain 90 percent ofthe variation in violent crime in America. Toddlerswho ingested high levels of lead in the 40s and50s really were more likely to become violent(55) criminals in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.And with that we have our molecule: tetra-ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented byGeneral Motors in the 1920s to prevent knockingand pinging in high-performance engines. As(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and driversin powerful new cars increasingly asked servicestation attendants to “fill er up with ethyl,” theywere unwittingly creating a crime wave twodecades later.(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and itprompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.Nevins paper was almost completely ignored,and in one sense its easy to see why—Nevin isan economist, not a criminologist, and his paper(70) was published in Environmental Research, not ajournal with a big readership in the criminologycommunity. Whats more, a single correlationbetween two curves isnt all that impressive,econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined inthe 80s and 90s. No matter how good the fit, ifyou only have a single correlation it might just bea coincidence. You need to do something more toestablish causality.(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data andcrime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and WestGermany. Every time, the two curves fit each otherastonishingly well.(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explainsome things we might not have realized evenneeded explaining. For example, murder rateshave always been higher in big cities than intowns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a smallarea, they also had high densities of atmosphericlead during the postwar era. But as lead levelsin gasoline decreased, the differences betweenbig and small cities largely went away. And guess(95) what? The difference in murder rates went awaytoo. Today, homicide rates are similar in citiesof all sizes. It may be that violent crime isnt aninevitable consequence of being a big city after all.*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.Q.In line 49, “even better” most nearly meansa)less controversial.b)more correlative.c)easier to calculate.d)more aesthetically engaging.Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?.

Solutions for Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “Americas Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.Experts often suggest that crime resemblesan epidemic. But what kind? Economicsprofessor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumbfor categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause isinformation. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travelsalong major transportation routes, the cause ismicrobial. Think influenza. If it spreads out likea fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But(10) if its everywhere, all at once—as both the rise ofcrime in the 60s and 70s and the fall of crime inthe 90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.A molecule? That sounds crazy. Whatmolecule could be responsible for a steep and(15) sudden decline in violent crime?Well, heres one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultantworking for the US Department of Housing andUrban Development on the costs and benefits of(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growingbody of research had linked lead exposure insmall children with a whole raft of complicationslater in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.(25) A recent study had also suggested a linkbetween childhood lead exposure and juveniledelinquency later on. Maybe reducing leadexposure had an effect on violent crime too?That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turnsout, wasnt paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chartthe rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused bythe rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early 40s throughthe early 70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leadedgasoline, emissions plummeted.Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). Theonly thing different was the time period. Crimerates rose dramatically in the 60s through the80s, and then began dropping steadily startingin the early 90s. The two curves looked eerily(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.So Nevin dug up detailed data on leademissions and crime rates to see if the similarityof the curves was as good as it seemed. It turnedout to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, leademissions from automobiles explain 90 percent ofthe variation in violent crime in America. Toddlerswho ingested high levels of lead in the 40s and50s really were more likely to become violent(55) criminals in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.And with that we have our molecule: tetra-ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented byGeneral Motors in the 1920s to prevent knockingand pinging in high-performance engines. As(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and driversin powerful new cars increasingly asked servicestation attendants to “fill er up with ethyl,” theywere unwittingly creating a crime wave twodecades later.(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and itprompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.Nevins paper was almost completely ignored,and in one sense its easy to see why—Nevin isan economist, not a criminologist, and his paper(70) was published in Environmental Research, not ajournal with a big readership in the criminologycommunity. Whats more, a single correlationbetween two curves isnt all that impressive,econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined inthe 80s and 90s. No matter how good the fit, ifyou only have a single correlation it might just bea coincidence. You need to do something more toestablish causality.(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data andcrime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and WestGermany. Every time, the two curves fit each otherastonishingly well.(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explainsome things we might not have realized evenneeded explaining. For example, murder rateshave always been higher in big cities than intowns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a smallarea, they also had high densities of atmosphericlead during the postwar era. But as lead levelsin gasoline decreased, the differences betweenbig and small cities largely went away. And guess(95) what? The difference in murder rates went awaytoo. Today, homicide rates are similar in citiesof all sizes. It may be that violent crime isnt aninevitable consequence of being a big city after all.*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.Q.In line 49, “even better” most nearly meansa)less controversial.b)more correlative.c)easier to calculate.d)more aesthetically engaging.Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? in English & in Hindi are available as part of our courses for SAT.

Download more important topics, notes, lectures and mock test series for SAT Exam by signing up for free.

Here you can find the meaning of Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “Americas Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.Experts often suggest that crime resemblesan epidemic. But what kind? Economicsprofessor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumbfor categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause isinformation. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travelsalong major transportation routes, the cause ismicrobial. Think influenza. If it spreads out likea fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But(10) if its everywhere, all at once—as both the rise ofcrime in the 60s and 70s and the fall of crime inthe 90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.A molecule? That sounds crazy. Whatmolecule could be responsible for a steep and(15) sudden decline in violent crime?Well, heres one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultantworking for the US Department of Housing andUrban Development on the costs and benefits of(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growingbody of research had linked lead exposure insmall children with a whole raft of complicationslater in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.(25) A recent study had also suggested a linkbetween childhood lead exposure and juveniledelinquency later on. Maybe reducing leadexposure had an effect on violent crime too?That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turnsout, wasnt paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chartthe rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused bythe rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early 40s throughthe early 70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leadedgasoline, emissions plummeted.Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). Theonly thing different was the time period. Crimerates rose dramatically in the 60s through the80s, and then began dropping steadily startingin the early 90s. The two curves looked eerily(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.So Nevin dug up detailed data on leademissions and crime rates to see if the similarityof the curves was as good as it seemed. It turnedout to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, leademissions from automobiles explain 90 percent ofthe variation in violent crime in America. Toddlerswho ingested high levels of lead in the 40s and50s really were more likely to become violent(55) criminals in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.And with that we have our molecule: tetra-ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented byGeneral Motors in the 1920s to prevent knockingand pinging in high-performance engines. As(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and driversin powerful new cars increasingly asked servicestation attendants to “fill er up with ethyl,” theywere unwittingly creating a crime wave twodecades later.(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and itprompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.Nevins paper was almost completely ignored,and in one sense its easy to see why—Nevin isan economist, not a criminologist, and his paper(70) was published in Environmental Research, not ajournal with a big readership in the criminologycommunity. Whats more, a single correlationbetween two curves isnt all that impressive,econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined inthe 80s and 90s. No matter how good the fit, ifyou only have a single correlation it might just bea coincidence. You need to do something more toestablish causality.(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data andcrime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and WestGermany. Every time, the two curves fit each otherastonishingly well.(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explainsome things we might not have realized evenneeded explaining. For example, murder rateshave always been higher in big cities than intowns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a smallarea, they also had high densities of atmosphericlead during the postwar era. But as lead levelsin gasoline decreased, the differences betweenbig and small cities largely went away. And guess(95) what? The difference in murder rates went awaytoo. Today, homicide rates are similar in citiesof all sizes. It may be that violent crime isnt aninevitable consequence of being a big city after all.*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.Q.In line 49, “even better” most nearly meansa)less controversial.b)more correlative.c)easier to calculate.d)more aesthetically engaging.Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? defined & explained in the simplest way possible. Besides giving the explanation of

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “Americas Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.Experts often suggest that crime resemblesan epidemic. But what kind? Economicsprofessor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumbfor categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause isinformation. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travelsalong major transportation routes, the cause ismicrobial. Think influenza. If it spreads out likea fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But(10) if its everywhere, all at once—as both the rise ofcrime in the 60s and 70s and the fall of crime inthe 90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.A molecule? That sounds crazy. Whatmolecule could be responsible for a steep and(15) sudden decline in violent crime?Well, heres one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultantworking for the US Department of Housing andUrban Development on the costs and benefits of(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growingbody of research had linked lead exposure insmall children with a whole raft of complicationslater in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.(25) A recent study had also suggested a linkbetween childhood lead exposure and juveniledelinquency later on. Maybe reducing leadexposure had an effect on violent crime too?That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turnsout, wasnt paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chartthe rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused bythe rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early 40s throughthe early 70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leadedgasoline, emissions plummeted.Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). Theonly thing different was the time period. Crimerates rose dramatically in the 60s through the80s, and then began dropping steadily startingin the early 90s. The two curves looked eerily(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.So Nevin dug up detailed data on leademissions and crime rates to see if the similarityof the curves was as good as it seemed. It turnedout to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, leademissions from automobiles explain 90 percent ofthe variation in violent crime in America. Toddlerswho ingested high levels of lead in the 40s and50s really were more likely to become violent(55) criminals in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.And with that we have our molecule: tetra-ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented byGeneral Motors in the 1920s to prevent knockingand pinging in high-performance engines. As(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and driversin powerful new cars increasingly asked servicestation attendants to “fill er up with ethyl,” theywere unwittingly creating a crime wave twodecades later.(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and itprompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.Nevins paper was almost completely ignored,and in one sense its easy to see why—Nevin isan economist, not a criminologist, and his paper(70) was published in Environmental Research, not ajournal with a big readership in the criminologycommunity. Whats more, a single correlationbetween two curves isnt all that impressive,econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined inthe 80s and 90s. No matter how good the fit, ifyou only have a single correlation it might just bea coincidence. You need to do something more toestablish causality.(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data andcrime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and WestGermany. Every time, the two curves fit each otherastonishingly well.(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explainsome things we might not have realized evenneeded explaining. For example, murder rateshave always been higher in big cities than intowns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a smallarea, they also had high densities of atmosphericlead during the postwar era. But as lead levelsin gasoline decreased, the differences betweenbig and small cities largely went away. And guess(95) what? The difference in murder rates went awaytoo. Today, homicide rates are similar in citiesof all sizes. It may be that violent crime isnt aninevitable consequence of being a big city after all.*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.Q.In line 49, “even better” most nearly meansa)less controversial.b)more correlative.c)easier to calculate.d)more aesthetically engaging.Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?, a detailed solution for Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “Americas Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.Experts often suggest that crime resemblesan epidemic. But what kind? Economicsprofessor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumbfor categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause isinformation. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travelsalong major transportation routes, the cause ismicrobial. Think influenza. If it spreads out likea fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But(10) if its everywhere, all at once—as both the rise ofcrime in the 60s and 70s and the fall of crime inthe 90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.A molecule? That sounds crazy. Whatmolecule could be responsible for a steep and(15) sudden decline in violent crime?Well, heres one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultantworking for the US Department of Housing andUrban Development on the costs and benefits of(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growingbody of research had linked lead exposure insmall children with a whole raft of complicationslater in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.(25) A recent study had also suggested a linkbetween childhood lead exposure and juveniledelinquency later on. Maybe reducing leadexposure had an effect on violent crime too?That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turnsout, wasnt paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chartthe rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused bythe rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early 40s throughthe early 70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leadedgasoline, emissions plummeted.Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). Theonly thing different was the time period. Crimerates rose dramatically in the 60s through the80s, and then began dropping steadily startingin the early 90s. The two curves looked eerily(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.So Nevin dug up detailed data on leademissions and crime rates to see if the similarityof the curves was as good as it seemed. It turnedout to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, leademissions from automobiles explain 90 percent ofthe variation in violent crime in America. Toddlerswho ingested high levels of lead in the 40s and50s really were more likely to become violent(55) criminals in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.And with that we have our molecule: tetra-ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented byGeneral Motors in the 1920s to prevent knockingand pinging in high-performance engines. As(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and driversin powerful new cars increasingly asked servicestation attendants to “fill er up with ethyl,” theywere unwittingly creating a crime wave twodecades later.(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and itprompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.Nevins paper was almost completely ignored,and in one sense its easy to see why—Nevin isan economist, not a criminologist, and his paper(70) was published in Environmental Research, not ajournal with a big readership in the criminologycommunity. Whats more, a single correlationbetween two curves isnt all that impressive,econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined inthe 80s and 90s. No matter how good the fit, ifyou only have a single correlation it might just bea coincidence. You need to do something more toestablish causality.(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data andcrime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and WestGermany. Every time, the two curves fit each otherastonishingly well.(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explainsome things we might not have realized evenneeded explaining. For example, murder rateshave always been higher in big cities than intowns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a smallarea, they also had high densities of atmosphericlead during the postwar era. But as lead levelsin gasoline decreased, the differences betweenbig and small cities largely went away. And guess(95) what? The difference in murder rates went awaytoo. Today, homicide rates are similar in citiesof all sizes. It may be that violent crime isnt aninevitable consequence of being a big city after all.*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.Q.In line 49, “even better” most nearly meansa)less controversial.b)more correlative.c)easier to calculate.d)more aesthetically engaging.Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? has been provided alongside types of Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “Americas Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.Experts often suggest that crime resemblesan epidemic. But what kind? Economicsprofessor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumbfor categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause isinformation. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travelsalong major transportation routes, the cause ismicrobial. Think influenza. If it spreads out likea fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But(10) if its everywhere, all at once—as both the rise ofcrime in the 60s and 70s and the fall of crime inthe 90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.A molecule? That sounds crazy. Whatmolecule could be responsible for a steep and(15) sudden decline in violent crime?Well, heres one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultantworking for the US Department of Housing andUrban Development on the costs and benefits of(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growingbody of research had linked lead exposure insmall children with a whole raft of complicationslater in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.(25) A recent study had also suggested a linkbetween childhood lead exposure and juveniledelinquency later on. Maybe reducing leadexposure had an effect on violent crime too?That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turnsout, wasnt paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chartthe rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused bythe rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early 40s throughthe early 70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leadedgasoline, emissions plummeted.Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). Theonly thing different was the time period. Crimerates rose dramatically in the 60s through the80s, and then began dropping steadily startingin the early 90s. The two curves looked eerily(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.So Nevin dug up detailed data on leademissions and crime rates to see if the similarityof the curves was as good as it seemed. It turnedout to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, leademissions from automobiles explain 90 percent ofthe variation in violent crime in America. Toddlerswho ingested high levels of lead in the 40s and50s really were more likely to become violent(55) criminals in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.And with that we have our molecule: tetra-ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented byGeneral Motors in the 1920s to prevent knockingand pinging in high-performance engines. As(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and driversin powerful new cars increasingly asked servicestation attendants to “fill er up with ethyl,” theywere unwittingly creating a crime wave twodecades later.(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and itprompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.Nevins paper was almost completely ignored,and in one sense its easy to see why—Nevin isan economist, not a criminologist, and his paper(70) was published in Environmental Research, not ajournal with a big readership in the criminologycommunity. Whats more, a single correlationbetween two curves isnt all that impressive,econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined inthe 80s and 90s. No matter how good the fit, ifyou only have a single correlation it might just bea coincidence. You need to do something more toestablish causality.(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data andcrime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and WestGermany. Every time, the two curves fit each otherastonishingly well.(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explainsome things we might not have realized evenneeded explaining. For example, murder rateshave always been higher in big cities than intowns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a smallarea, they also had high densities of atmosphericlead during the postwar era. But as lead levelsin gasoline decreased, the differences betweenbig and small cities largely went away. And guess(95) what? The difference in murder rates went awaytoo. Today, homicide rates are similar in citiesof all sizes. It may be that violent crime isnt aninevitable consequence of being a big city after all.*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.Q.In line 49, “even better” most nearly meansa)less controversial.b)more correlative.c)easier to calculate.d)more aesthetically engaging.Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? theory, EduRev gives you an

ample number of questions to practice Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “Americas Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.Experts often suggest that crime resemblesan epidemic. But what kind? Economicsprofessor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumbfor categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause isinformation. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travelsalong major transportation routes, the cause ismicrobial. Think influenza. If it spreads out likea fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But(10) if its everywhere, all at once—as both the rise ofcrime in the 60s and 70s and the fall of crime inthe 90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.A molecule? That sounds crazy. Whatmolecule could be responsible for a steep and(15) sudden decline in violent crime?Well, heres one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultantworking for the US Department of Housing andUrban Development on the costs and benefits of(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growingbody of research had linked lead exposure insmall children with a whole raft of complicationslater in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.(25) A recent study had also suggested a linkbetween childhood lead exposure and juveniledelinquency later on. Maybe reducing leadexposure had an effect on violent crime too?That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turnsout, wasnt paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chartthe rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused bythe rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early 40s throughthe early 70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leadedgasoline, emissions plummeted.Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). Theonly thing different was the time period. Crimerates rose dramatically in the 60s through the80s, and then began dropping steadily startingin the early 90s. The two curves looked eerily(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.So Nevin dug up detailed data on leademissions and crime rates to see if the similarityof the curves was as good as it seemed. It turnedout to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, leademissions from automobiles explain 90 percent ofthe variation in violent crime in America. Toddlerswho ingested high levels of lead in the 40s and50s really were more likely to become violent(55) criminals in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.And with that we have our molecule: tetra-ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented byGeneral Motors in the 1920s to prevent knockingand pinging in high-performance engines. As(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and driversin powerful new cars increasingly asked servicestation attendants to “fill er up with ethyl,” theywere unwittingly creating a crime wave twodecades later.(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and itprompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.Nevins paper was almost completely ignored,and in one sense its easy to see why—Nevin isan economist, not a criminologist, and his paper(70) was published in Environmental Research, not ajournal with a big readership in the criminologycommunity. Whats more, a single correlationbetween two curves isnt all that impressive,econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined inthe 80s and 90s. No matter how good the fit, ifyou only have a single correlation it might just bea coincidence. You need to do something more toestablish causality.(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data andcrime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and WestGermany. Every time, the two curves fit each otherastonishingly well.(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explainsome things we might not have realized evenneeded explaining. For example, murder rateshave always been higher in big cities than intowns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a smallarea, they also had high densities of atmosphericlead during the postwar era. But as lead levelsin gasoline decreased, the differences betweenbig and small cities largely went away. And guess(95) what? The difference in murder rates went awaytoo. Today, homicide rates are similar in citiesof all sizes. It may be that violent crime isnt aninevitable consequence of being a big city after all.*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.Q.In line 49, “even better” most nearly meansa)less controversial.b)more correlative.c)easier to calculate.d)more aesthetically engaging.Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? tests, examples and also practice SAT tests.

|

Explore Courses for SAT exam

|

|

Signup for Free!

Signup to see your scores go up within 7 days! Learn & Practice with 1000+ FREE Notes, Videos & Tests.