SAT Exam > SAT Questions > Question based on the following passage and s...

Start Learning for Free

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is from A. R. Kirchoff, “The New Ecosystems of the Anthropocene" ©2017 by College Hill Coaching.

Scavengers—animals that feed on carcasses,

rotting plants, or waste—get a bad rap.

Yellowjackets and raccoons swarming around

garbage cans can seem like annoying pests at

(5) best and germ-infested monsters at worst. Indeed,

scavengers have been known to spread diseases

such as meningitis, leptospirosis, and bubonic

plague, so it's no surprise that they are the focus

of a huge extermination industry. But our habit of

(10) eradicating irksome species ignores an important

fact: scavenger relationships are essential to all

complex life.

The selective pressures of scavenger behavior

accelerate the evolution of social intelligence.

(15) For thousands of generations, some scavenger

species have struggled to outwit the wily hunters

with whom they compete for scraps. They

must predict, plan, and communicate as they

approach a carcass in order to avoid becoming

(20) the next prey. At the same time, hunters like

Homo sapiens had to become more clever to

protect their meat from these thieves. This social

interaction has allowed at least one scavenger

species to thrive in an anthropocentric* world:

(25) Canis lupus familiaris—the domesticated dog.

Your pet terrier would not be such a faithful

companion if its ancestor, the grey wolf, had

not spend so much time picking over the trash

of our hunter forebears. In just 20,000 years, we

(30) have become symbionts,* turning a few lines of

wolves from freeloading foragers into friendly

Frisbee-fetchers.

Even less perspicacious scavengers play

a vital role in complex ecosystems, often in

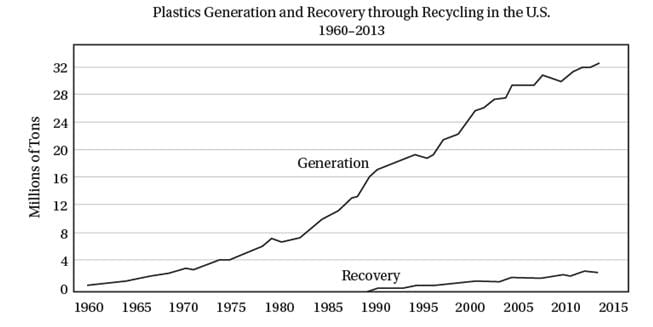

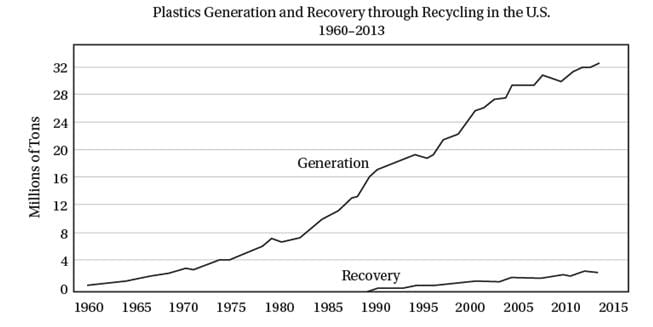

(35) unexpected ways. As plastic waste accumulates

rapidly in the ocean (and is expected to surpass

the total mass of fish by 2050), and toxic

chemical waste continues to be dumped into

our water supplies, the role of one particular

(40) class of scavenger, the decomposers, has become

critical. These creatures break down complex

molecules into simpler ones in a process called

biodegradation. Alcanivorax borkumensis, a

naturally occurring marine bacterium, can

(45) digest petroleum and convert it into food

energy. Hydrocarbons like petroleum and

plastics are energy-rich organic molecules

much like starches, fats, and proteins, so

the idea that they can be used as food by

(50) opportunistic organisms is not so biochemically

far-fetched. After crude oil spills, cleanup

crews encourage this biodegradation by using

chemical dispersant to break the petroleum

into smaller droplets, thereby creating more

(55) surface area for the bacteria to attack. Another

decomposer, Aspergillus tubingensis, is able to

greatly accelerate the breakdown of polyester

polyurethane, a petroleum product and one of

the more durable plastics in our landfills and

(60) oceans. Although environmentalists have yet

to discover a practical method for harnessing

A. tubingensis in large-scale waste mitigation

systems, such bio-technological solutions may

not be far off.

(65) Our dependence on unicellular opportunists

goes deeper still: our digestive processes,

blood pressure, and immune system depend

on thousands of species of scavenger bacteria

that live primarily in our gut and make up our

(70) microbiome. These organisms patrol the intricate

chemical pathways of the gut and perform duties

that, under normal circumstances, keep things

running smoothly. The overuse of antibiotics,

our favorite pharmaceutical pest-control system,

(75) often compromise healthy systemic function by

destroying healthful bacteria as well as harmful

ones. For instance, humans with depleted levels

of Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum in their intestines

have higher rates of chronic bowel diseases like

(80) ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Research

into how these microorganisms has exploded

in recent years, particularly regarding how they

interact with human chemistry to regulate our

hormones, our blood sugar, and even our mood.

* human-centered

* species that live together in a mutually supportive relationship.

This passage is from A. R. Kirchoff, “The New Ecosystems of the Anthropocene" ©2017 by College Hill Coaching.

Scavengers—animals that feed on carcasses,

rotting plants, or waste—get a bad rap.

Yellowjackets and raccoons swarming around

garbage cans can seem like annoying pests at

(5) best and germ-infested monsters at worst. Indeed,

scavengers have been known to spread diseases

such as meningitis, leptospirosis, and bubonic

plague, so it's no surprise that they are the focus

of a huge extermination industry. But our habit of

(10) eradicating irksome species ignores an important

fact: scavenger relationships are essential to all

complex life.

The selective pressures of scavenger behavior

accelerate the evolution of social intelligence.

(15) For thousands of generations, some scavenger

species have struggled to outwit the wily hunters

with whom they compete for scraps. They

must predict, plan, and communicate as they

approach a carcass in order to avoid becoming

(20) the next prey. At the same time, hunters like

Homo sapiens had to become more clever to

protect their meat from these thieves. This social

interaction has allowed at least one scavenger

species to thrive in an anthropocentric* world:

(25) Canis lupus familiaris—the domesticated dog.

Your pet terrier would not be such a faithful

companion if its ancestor, the grey wolf, had

not spend so much time picking over the trash

of our hunter forebears. In just 20,000 years, we

(30) have become symbionts,* turning a few lines of

wolves from freeloading foragers into friendly

Frisbee-fetchers.

Even less perspicacious scavengers play

a vital role in complex ecosystems, often in

(35) unexpected ways. As plastic waste accumulates

rapidly in the ocean (and is expected to surpass

the total mass of fish by 2050), and toxic

chemical waste continues to be dumped into

our water supplies, the role of one particular

(40) class of scavenger, the decomposers, has become

critical. These creatures break down complex

molecules into simpler ones in a process called

biodegradation. Alcanivorax borkumensis, a

naturally occurring marine bacterium, can

(45) digest petroleum and convert it into food

energy. Hydrocarbons like petroleum and

plastics are energy-rich organic molecules

much like starches, fats, and proteins, so

the idea that they can be used as food by

(50) opportunistic organisms is not so biochemically

far-fetched. After crude oil spills, cleanup

crews encourage this biodegradation by using

chemical dispersant to break the petroleum

into smaller droplets, thereby creating more

(55) surface area for the bacteria to attack. Another

decomposer, Aspergillus tubingensis, is able to

greatly accelerate the breakdown of polyester

polyurethane, a petroleum product and one of

the more durable plastics in our landfills and

(60) oceans. Although environmentalists have yet

to discover a practical method for harnessing

A. tubingensis in large-scale waste mitigation

systems, such bio-technological solutions may

not be far off.

(65) Our dependence on unicellular opportunists

goes deeper still: our digestive processes,

blood pressure, and immune system depend

on thousands of species of scavenger bacteria

that live primarily in our gut and make up our

(70) microbiome. These organisms patrol the intricate

chemical pathways of the gut and perform duties

that, under normal circumstances, keep things

running smoothly. The overuse of antibiotics,

our favorite pharmaceutical pest-control system,

(75) often compromise healthy systemic function by

destroying healthful bacteria as well as harmful

ones. For instance, humans with depleted levels

of Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum in their intestines

have higher rates of chronic bowel diseases like

(80) ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Research

into how these microorganisms has exploded

in recent years, particularly regarding how they

interact with human chemistry to regulate our

hormones, our blood sugar, and even our mood.

* human-centered

* species that live together in a mutually supportive relationship.

Q. Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

- a)Lines 13–14 (“The selective . . . intelligence”)

- b)Lines 17–20 (“They must . . . prey”)

- c)Lines 20–22 (“At . . . thieves”)

- d)Lines 26–29 (“Your pet . . . forebears”)

Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?

Most Upvoted Answer

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Thi...

As the explanation to question 46 indicates, the best evidence for this answer can be found in lines 17-20.

|

Explore Courses for SAT exam

|

|

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is from A. R. Kirchoff, “The New Ecosystems of the Anthropocene" ©2017 by College Hill Coaching.Scavengers—animals that feed on carcasses,rotting plants, or waste—get a bad rap.Yellowjackets and raccoons swarming aroundgarbage cans can seem like annoying pests at(5) best and germ-infested monsters at worst. Indeed,scavengers have been known to spread diseasessuch as meningitis, leptospirosis, and bubonicplague, so its no surprise that they are the focusof a huge extermination industry. But our habit of(10) eradicating irksome species ignores an importantfact: scavenger relationships are essential to allcomplex life.The selective pressures of scavenger behavioraccelerate the evolution of social intelligence.(15) For thousands of generations, some scavengerspecies have struggled to outwit the wily hunterswith whom they compete for scraps. Theymust predict, plan, and communicate as theyapproach a carcass in order to avoid becoming(20) the next prey. At the same time, hunters likeHomo sapiens had to become more clever toprotect their meat from these thieves. This socialinteraction has allowed at least one scavengerspecies to thrive in an anthropocentric* world:(25) Canis lupus familiaris—the domesticated dog.Your pet terrier would not be such a faithfulcompanion if its ancestor, the grey wolf, hadnot spend so much time picking over the trashof our hunter forebears. In just 20,000 years, we(30) have become symbionts,* turning a few lines ofwolves from freeloading foragers into friendlyFrisbee-fetchers.Even less perspicacious scavengers playa vital role in complex ecosystems, often in(35) unexpected ways. As plastic waste accumulatesrapidly in the ocean (and is expected to surpassthe total mass of fish by 2050), and toxicchemical waste continues to be dumped intoour water supplies, the role of one particular(40) class of scavenger, the decomposers, has becomecritical. These creatures break down complexmolecules into simpler ones in a process calledbiodegradation. Alcanivorax borkumensis, anaturally occurring marine bacterium, can(45) digest petroleum and convert it into foodenergy. Hydrocarbons like petroleum andplastics are energy-rich organic moleculesmuch like starches, fats, and proteins, sothe idea that they can be used as food by(50) opportunistic organisms is not so biochemicallyfar-fetched. After crude oil spills, cleanupcrews encourage this biodegradation by usingchemical dispersant to break the petroleuminto smaller droplets, thereby creating more(55) surface area for the bacteria to attack. Anotherdecomposer, Aspergillus tubingensis, is able togreatly accelerate the breakdown of polyesterpolyurethane, a petroleum product and one ofthe more durable plastics in our landfills and(60) oceans. Although environmentalists have yetto discover a practical method for harnessingA. tubingensis in large-scale waste mitigationsystems, such bio-technological solutions maynot be far off.(65) Our dependence on unicellular opportunistsgoes deeper still: our digestive processes,blood pressure, and immune system dependon thousands of species of scavenger bacteriathat live primarily in our gut and make up our(70) microbiome. These organisms patrol the intricatechemical pathways of the gut and perform dutiesthat, under normal circumstances, keep thingsrunning smoothly. The overuse of antibiotics,our favorite pharmaceutical pest-control system,(75) often compromise healthy systemic function bydestroying healthful bacteria as well as harmfulones. For instance, humans with depleted levelsof Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum in their intestineshave higher rates of chronic bowel diseases like(80) ulcerative colitis and Crohns disease. Researchinto how these microorganisms has explodedin recent years, particularly regarding how theyinteract with human chemistry to regulate ourhormones, our blood sugar, and even our mood.*human-centered*species that live together in a mutually supportive relationship.Q.Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?a)Lines 13–14 (“The selective . . . intelligence”)b)Lines 17–20 (“They must . . . prey”)c)Lines 20–22 (“At . . . thieves”)d)Lines 26–29 (“Your pet . . . forebears”)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?

Question Description

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is from A. R. Kirchoff, “The New Ecosystems of the Anthropocene" ©2017 by College Hill Coaching.Scavengers—animals that feed on carcasses,rotting plants, or waste—get a bad rap.Yellowjackets and raccoons swarming aroundgarbage cans can seem like annoying pests at(5) best and germ-infested monsters at worst. Indeed,scavengers have been known to spread diseasessuch as meningitis, leptospirosis, and bubonicplague, so its no surprise that they are the focusof a huge extermination industry. But our habit of(10) eradicating irksome species ignores an importantfact: scavenger relationships are essential to allcomplex life.The selective pressures of scavenger behavioraccelerate the evolution of social intelligence.(15) For thousands of generations, some scavengerspecies have struggled to outwit the wily hunterswith whom they compete for scraps. Theymust predict, plan, and communicate as theyapproach a carcass in order to avoid becoming(20) the next prey. At the same time, hunters likeHomo sapiens had to become more clever toprotect their meat from these thieves. This socialinteraction has allowed at least one scavengerspecies to thrive in an anthropocentric* world:(25) Canis lupus familiaris—the domesticated dog.Your pet terrier would not be such a faithfulcompanion if its ancestor, the grey wolf, hadnot spend so much time picking over the trashof our hunter forebears. In just 20,000 years, we(30) have become symbionts,* turning a few lines ofwolves from freeloading foragers into friendlyFrisbee-fetchers.Even less perspicacious scavengers playa vital role in complex ecosystems, often in(35) unexpected ways. As plastic waste accumulatesrapidly in the ocean (and is expected to surpassthe total mass of fish by 2050), and toxicchemical waste continues to be dumped intoour water supplies, the role of one particular(40) class of scavenger, the decomposers, has becomecritical. These creatures break down complexmolecules into simpler ones in a process calledbiodegradation. Alcanivorax borkumensis, anaturally occurring marine bacterium, can(45) digest petroleum and convert it into foodenergy. Hydrocarbons like petroleum andplastics are energy-rich organic moleculesmuch like starches, fats, and proteins, sothe idea that they can be used as food by(50) opportunistic organisms is not so biochemicallyfar-fetched. After crude oil spills, cleanupcrews encourage this biodegradation by usingchemical dispersant to break the petroleuminto smaller droplets, thereby creating more(55) surface area for the bacteria to attack. Anotherdecomposer, Aspergillus tubingensis, is able togreatly accelerate the breakdown of polyesterpolyurethane, a petroleum product and one ofthe more durable plastics in our landfills and(60) oceans. Although environmentalists have yetto discover a practical method for harnessingA. tubingensis in large-scale waste mitigationsystems, such bio-technological solutions maynot be far off.(65) Our dependence on unicellular opportunistsgoes deeper still: our digestive processes,blood pressure, and immune system dependon thousands of species of scavenger bacteriathat live primarily in our gut and make up our(70) microbiome. These organisms patrol the intricatechemical pathways of the gut and perform dutiesthat, under normal circumstances, keep thingsrunning smoothly. The overuse of antibiotics,our favorite pharmaceutical pest-control system,(75) often compromise healthy systemic function bydestroying healthful bacteria as well as harmfulones. For instance, humans with depleted levelsof Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum in their intestineshave higher rates of chronic bowel diseases like(80) ulcerative colitis and Crohns disease. Researchinto how these microorganisms has explodedin recent years, particularly regarding how theyinteract with human chemistry to regulate ourhormones, our blood sugar, and even our mood.*human-centered*species that live together in a mutually supportive relationship.Q.Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?a)Lines 13–14 (“The selective . . . intelligence”)b)Lines 17–20 (“They must . . . prey”)c)Lines 20–22 (“At . . . thieves”)d)Lines 26–29 (“Your pet . . . forebears”)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? for SAT 2025 is part of SAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the SAT exam syllabus. Information about Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is from A. R. Kirchoff, “The New Ecosystems of the Anthropocene" ©2017 by College Hill Coaching.Scavengers—animals that feed on carcasses,rotting plants, or waste—get a bad rap.Yellowjackets and raccoons swarming aroundgarbage cans can seem like annoying pests at(5) best and germ-infested monsters at worst. Indeed,scavengers have been known to spread diseasessuch as meningitis, leptospirosis, and bubonicplague, so its no surprise that they are the focusof a huge extermination industry. But our habit of(10) eradicating irksome species ignores an importantfact: scavenger relationships are essential to allcomplex life.The selective pressures of scavenger behavioraccelerate the evolution of social intelligence.(15) For thousands of generations, some scavengerspecies have struggled to outwit the wily hunterswith whom they compete for scraps. Theymust predict, plan, and communicate as theyapproach a carcass in order to avoid becoming(20) the next prey. At the same time, hunters likeHomo sapiens had to become more clever toprotect their meat from these thieves. This socialinteraction has allowed at least one scavengerspecies to thrive in an anthropocentric* world:(25) Canis lupus familiaris—the domesticated dog.Your pet terrier would not be such a faithfulcompanion if its ancestor, the grey wolf, hadnot spend so much time picking over the trashof our hunter forebears. In just 20,000 years, we(30) have become symbionts,* turning a few lines ofwolves from freeloading foragers into friendlyFrisbee-fetchers.Even less perspicacious scavengers playa vital role in complex ecosystems, often in(35) unexpected ways. As plastic waste accumulatesrapidly in the ocean (and is expected to surpassthe total mass of fish by 2050), and toxicchemical waste continues to be dumped intoour water supplies, the role of one particular(40) class of scavenger, the decomposers, has becomecritical. These creatures break down complexmolecules into simpler ones in a process calledbiodegradation. Alcanivorax borkumensis, anaturally occurring marine bacterium, can(45) digest petroleum and convert it into foodenergy. Hydrocarbons like petroleum andplastics are energy-rich organic moleculesmuch like starches, fats, and proteins, sothe idea that they can be used as food by(50) opportunistic organisms is not so biochemicallyfar-fetched. After crude oil spills, cleanupcrews encourage this biodegradation by usingchemical dispersant to break the petroleuminto smaller droplets, thereby creating more(55) surface area for the bacteria to attack. Anotherdecomposer, Aspergillus tubingensis, is able togreatly accelerate the breakdown of polyesterpolyurethane, a petroleum product and one ofthe more durable plastics in our landfills and(60) oceans. Although environmentalists have yetto discover a practical method for harnessingA. tubingensis in large-scale waste mitigationsystems, such bio-technological solutions maynot be far off.(65) Our dependence on unicellular opportunistsgoes deeper still: our digestive processes,blood pressure, and immune system dependon thousands of species of scavenger bacteriathat live primarily in our gut and make up our(70) microbiome. These organisms patrol the intricatechemical pathways of the gut and perform dutiesthat, under normal circumstances, keep thingsrunning smoothly. The overuse of antibiotics,our favorite pharmaceutical pest-control system,(75) often compromise healthy systemic function bydestroying healthful bacteria as well as harmfulones. For instance, humans with depleted levelsof Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum in their intestineshave higher rates of chronic bowel diseases like(80) ulcerative colitis and Crohns disease. Researchinto how these microorganisms has explodedin recent years, particularly regarding how theyinteract with human chemistry to regulate ourhormones, our blood sugar, and even our mood.*human-centered*species that live together in a mutually supportive relationship.Q.Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?a)Lines 13–14 (“The selective . . . intelligence”)b)Lines 17–20 (“They must . . . prey”)c)Lines 20–22 (“At . . . thieves”)d)Lines 26–29 (“Your pet . . . forebears”)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for SAT 2025 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is from A. R. Kirchoff, “The New Ecosystems of the Anthropocene" ©2017 by College Hill Coaching.Scavengers—animals that feed on carcasses,rotting plants, or waste—get a bad rap.Yellowjackets and raccoons swarming aroundgarbage cans can seem like annoying pests at(5) best and germ-infested monsters at worst. Indeed,scavengers have been known to spread diseasessuch as meningitis, leptospirosis, and bubonicplague, so its no surprise that they are the focusof a huge extermination industry. But our habit of(10) eradicating irksome species ignores an importantfact: scavenger relationships are essential to allcomplex life.The selective pressures of scavenger behavioraccelerate the evolution of social intelligence.(15) For thousands of generations, some scavengerspecies have struggled to outwit the wily hunterswith whom they compete for scraps. Theymust predict, plan, and communicate as theyapproach a carcass in order to avoid becoming(20) the next prey. At the same time, hunters likeHomo sapiens had to become more clever toprotect their meat from these thieves. This socialinteraction has allowed at least one scavengerspecies to thrive in an anthropocentric* world:(25) Canis lupus familiaris—the domesticated dog.Your pet terrier would not be such a faithfulcompanion if its ancestor, the grey wolf, hadnot spend so much time picking over the trashof our hunter forebears. In just 20,000 years, we(30) have become symbionts,* turning a few lines ofwolves from freeloading foragers into friendlyFrisbee-fetchers.Even less perspicacious scavengers playa vital role in complex ecosystems, often in(35) unexpected ways. As plastic waste accumulatesrapidly in the ocean (and is expected to surpassthe total mass of fish by 2050), and toxicchemical waste continues to be dumped intoour water supplies, the role of one particular(40) class of scavenger, the decomposers, has becomecritical. These creatures break down complexmolecules into simpler ones in a process calledbiodegradation. Alcanivorax borkumensis, anaturally occurring marine bacterium, can(45) digest petroleum and convert it into foodenergy. Hydrocarbons like petroleum andplastics are energy-rich organic moleculesmuch like starches, fats, and proteins, sothe idea that they can be used as food by(50) opportunistic organisms is not so biochemicallyfar-fetched. After crude oil spills, cleanupcrews encourage this biodegradation by usingchemical dispersant to break the petroleuminto smaller droplets, thereby creating more(55) surface area for the bacteria to attack. Anotherdecomposer, Aspergillus tubingensis, is able togreatly accelerate the breakdown of polyesterpolyurethane, a petroleum product and one ofthe more durable plastics in our landfills and(60) oceans. Although environmentalists have yetto discover a practical method for harnessingA. tubingensis in large-scale waste mitigationsystems, such bio-technological solutions maynot be far off.(65) Our dependence on unicellular opportunistsgoes deeper still: our digestive processes,blood pressure, and immune system dependon thousands of species of scavenger bacteriathat live primarily in our gut and make up our(70) microbiome. These organisms patrol the intricatechemical pathways of the gut and perform dutiesthat, under normal circumstances, keep thingsrunning smoothly. The overuse of antibiotics,our favorite pharmaceutical pest-control system,(75) often compromise healthy systemic function bydestroying healthful bacteria as well as harmfulones. For instance, humans with depleted levelsof Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum in their intestineshave higher rates of chronic bowel diseases like(80) ulcerative colitis and Crohns disease. Researchinto how these microorganisms has explodedin recent years, particularly regarding how theyinteract with human chemistry to regulate ourhormones, our blood sugar, and even our mood.*human-centered*species that live together in a mutually supportive relationship.Q.Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?a)Lines 13–14 (“The selective . . . intelligence”)b)Lines 17–20 (“They must . . . prey”)c)Lines 20–22 (“At . . . thieves”)d)Lines 26–29 (“Your pet . . . forebears”)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?.

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is from A. R. Kirchoff, “The New Ecosystems of the Anthropocene" ©2017 by College Hill Coaching.Scavengers—animals that feed on carcasses,rotting plants, or waste—get a bad rap.Yellowjackets and raccoons swarming aroundgarbage cans can seem like annoying pests at(5) best and germ-infested monsters at worst. Indeed,scavengers have been known to spread diseasessuch as meningitis, leptospirosis, and bubonicplague, so its no surprise that they are the focusof a huge extermination industry. But our habit of(10) eradicating irksome species ignores an importantfact: scavenger relationships are essential to allcomplex life.The selective pressures of scavenger behavioraccelerate the evolution of social intelligence.(15) For thousands of generations, some scavengerspecies have struggled to outwit the wily hunterswith whom they compete for scraps. Theymust predict, plan, and communicate as theyapproach a carcass in order to avoid becoming(20) the next prey. At the same time, hunters likeHomo sapiens had to become more clever toprotect their meat from these thieves. This socialinteraction has allowed at least one scavengerspecies to thrive in an anthropocentric* world:(25) Canis lupus familiaris—the domesticated dog.Your pet terrier would not be such a faithfulcompanion if its ancestor, the grey wolf, hadnot spend so much time picking over the trashof our hunter forebears. In just 20,000 years, we(30) have become symbionts,* turning a few lines ofwolves from freeloading foragers into friendlyFrisbee-fetchers.Even less perspicacious scavengers playa vital role in complex ecosystems, often in(35) unexpected ways. As plastic waste accumulatesrapidly in the ocean (and is expected to surpassthe total mass of fish by 2050), and toxicchemical waste continues to be dumped intoour water supplies, the role of one particular(40) class of scavenger, the decomposers, has becomecritical. These creatures break down complexmolecules into simpler ones in a process calledbiodegradation. Alcanivorax borkumensis, anaturally occurring marine bacterium, can(45) digest petroleum and convert it into foodenergy. Hydrocarbons like petroleum andplastics are energy-rich organic moleculesmuch like starches, fats, and proteins, sothe idea that they can be used as food by(50) opportunistic organisms is not so biochemicallyfar-fetched. After crude oil spills, cleanupcrews encourage this biodegradation by usingchemical dispersant to break the petroleuminto smaller droplets, thereby creating more(55) surface area for the bacteria to attack. Anotherdecomposer, Aspergillus tubingensis, is able togreatly accelerate the breakdown of polyesterpolyurethane, a petroleum product and one ofthe more durable plastics in our landfills and(60) oceans. Although environmentalists have yetto discover a practical method for harnessingA. tubingensis in large-scale waste mitigationsystems, such bio-technological solutions maynot be far off.(65) Our dependence on unicellular opportunistsgoes deeper still: our digestive processes,blood pressure, and immune system dependon thousands of species of scavenger bacteriathat live primarily in our gut and make up our(70) microbiome. These organisms patrol the intricatechemical pathways of the gut and perform dutiesthat, under normal circumstances, keep thingsrunning smoothly. The overuse of antibiotics,our favorite pharmaceutical pest-control system,(75) often compromise healthy systemic function bydestroying healthful bacteria as well as harmfulones. For instance, humans with depleted levelsof Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum in their intestineshave higher rates of chronic bowel diseases like(80) ulcerative colitis and Crohns disease. Researchinto how these microorganisms has explodedin recent years, particularly regarding how theyinteract with human chemistry to regulate ourhormones, our blood sugar, and even our mood.*human-centered*species that live together in a mutually supportive relationship.Q.Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?a)Lines 13–14 (“The selective . . . intelligence”)b)Lines 17–20 (“They must . . . prey”)c)Lines 20–22 (“At . . . thieves”)d)Lines 26–29 (“Your pet . . . forebears”)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? for SAT 2025 is part of SAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the SAT exam syllabus. Information about Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is from A. R. Kirchoff, “The New Ecosystems of the Anthropocene" ©2017 by College Hill Coaching.Scavengers—animals that feed on carcasses,rotting plants, or waste—get a bad rap.Yellowjackets and raccoons swarming aroundgarbage cans can seem like annoying pests at(5) best and germ-infested monsters at worst. Indeed,scavengers have been known to spread diseasessuch as meningitis, leptospirosis, and bubonicplague, so its no surprise that they are the focusof a huge extermination industry. But our habit of(10) eradicating irksome species ignores an importantfact: scavenger relationships are essential to allcomplex life.The selective pressures of scavenger behavioraccelerate the evolution of social intelligence.(15) For thousands of generations, some scavengerspecies have struggled to outwit the wily hunterswith whom they compete for scraps. Theymust predict, plan, and communicate as theyapproach a carcass in order to avoid becoming(20) the next prey. At the same time, hunters likeHomo sapiens had to become more clever toprotect their meat from these thieves. This socialinteraction has allowed at least one scavengerspecies to thrive in an anthropocentric* world:(25) Canis lupus familiaris—the domesticated dog.Your pet terrier would not be such a faithfulcompanion if its ancestor, the grey wolf, hadnot spend so much time picking over the trashof our hunter forebears. In just 20,000 years, we(30) have become symbionts,* turning a few lines ofwolves from freeloading foragers into friendlyFrisbee-fetchers.Even less perspicacious scavengers playa vital role in complex ecosystems, often in(35) unexpected ways. As plastic waste accumulatesrapidly in the ocean (and is expected to surpassthe total mass of fish by 2050), and toxicchemical waste continues to be dumped intoour water supplies, the role of one particular(40) class of scavenger, the decomposers, has becomecritical. These creatures break down complexmolecules into simpler ones in a process calledbiodegradation. Alcanivorax borkumensis, anaturally occurring marine bacterium, can(45) digest petroleum and convert it into foodenergy. Hydrocarbons like petroleum andplastics are energy-rich organic moleculesmuch like starches, fats, and proteins, sothe idea that they can be used as food by(50) opportunistic organisms is not so biochemicallyfar-fetched. After crude oil spills, cleanupcrews encourage this biodegradation by usingchemical dispersant to break the petroleuminto smaller droplets, thereby creating more(55) surface area for the bacteria to attack. Anotherdecomposer, Aspergillus tubingensis, is able togreatly accelerate the breakdown of polyesterpolyurethane, a petroleum product and one ofthe more durable plastics in our landfills and(60) oceans. Although environmentalists have yetto discover a practical method for harnessingA. tubingensis in large-scale waste mitigationsystems, such bio-technological solutions maynot be far off.(65) Our dependence on unicellular opportunistsgoes deeper still: our digestive processes,blood pressure, and immune system dependon thousands of species of scavenger bacteriathat live primarily in our gut and make up our(70) microbiome. These organisms patrol the intricatechemical pathways of the gut and perform dutiesthat, under normal circumstances, keep thingsrunning smoothly. The overuse of antibiotics,our favorite pharmaceutical pest-control system,(75) often compromise healthy systemic function bydestroying healthful bacteria as well as harmfulones. For instance, humans with depleted levelsof Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum in their intestineshave higher rates of chronic bowel diseases like(80) ulcerative colitis and Crohns disease. Researchinto how these microorganisms has explodedin recent years, particularly regarding how theyinteract with human chemistry to regulate ourhormones, our blood sugar, and even our mood.*human-centered*species that live together in a mutually supportive relationship.Q.Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?a)Lines 13–14 (“The selective . . . intelligence”)b)Lines 17–20 (“They must . . . prey”)c)Lines 20–22 (“At . . . thieves”)d)Lines 26–29 (“Your pet . . . forebears”)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for SAT 2025 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is from A. R. Kirchoff, “The New Ecosystems of the Anthropocene" ©2017 by College Hill Coaching.Scavengers—animals that feed on carcasses,rotting plants, or waste—get a bad rap.Yellowjackets and raccoons swarming aroundgarbage cans can seem like annoying pests at(5) best and germ-infested monsters at worst. Indeed,scavengers have been known to spread diseasessuch as meningitis, leptospirosis, and bubonicplague, so its no surprise that they are the focusof a huge extermination industry. But our habit of(10) eradicating irksome species ignores an importantfact: scavenger relationships are essential to allcomplex life.The selective pressures of scavenger behavioraccelerate the evolution of social intelligence.(15) For thousands of generations, some scavengerspecies have struggled to outwit the wily hunterswith whom they compete for scraps. Theymust predict, plan, and communicate as theyapproach a carcass in order to avoid becoming(20) the next prey. At the same time, hunters likeHomo sapiens had to become more clever toprotect their meat from these thieves. This socialinteraction has allowed at least one scavengerspecies to thrive in an anthropocentric* world:(25) Canis lupus familiaris—the domesticated dog.Your pet terrier would not be such a faithfulcompanion if its ancestor, the grey wolf, hadnot spend so much time picking over the trashof our hunter forebears. In just 20,000 years, we(30) have become symbionts,* turning a few lines ofwolves from freeloading foragers into friendlyFrisbee-fetchers.Even less perspicacious scavengers playa vital role in complex ecosystems, often in(35) unexpected ways. As plastic waste accumulatesrapidly in the ocean (and is expected to surpassthe total mass of fish by 2050), and toxicchemical waste continues to be dumped intoour water supplies, the role of one particular(40) class of scavenger, the decomposers, has becomecritical. These creatures break down complexmolecules into simpler ones in a process calledbiodegradation. Alcanivorax borkumensis, anaturally occurring marine bacterium, can(45) digest petroleum and convert it into foodenergy. Hydrocarbons like petroleum andplastics are energy-rich organic moleculesmuch like starches, fats, and proteins, sothe idea that they can be used as food by(50) opportunistic organisms is not so biochemicallyfar-fetched. After crude oil spills, cleanupcrews encourage this biodegradation by usingchemical dispersant to break the petroleuminto smaller droplets, thereby creating more(55) surface area for the bacteria to attack. Anotherdecomposer, Aspergillus tubingensis, is able togreatly accelerate the breakdown of polyesterpolyurethane, a petroleum product and one ofthe more durable plastics in our landfills and(60) oceans. Although environmentalists have yetto discover a practical method for harnessingA. tubingensis in large-scale waste mitigationsystems, such bio-technological solutions maynot be far off.(65) Our dependence on unicellular opportunistsgoes deeper still: our digestive processes,blood pressure, and immune system dependon thousands of species of scavenger bacteriathat live primarily in our gut and make up our(70) microbiome. These organisms patrol the intricatechemical pathways of the gut and perform dutiesthat, under normal circumstances, keep thingsrunning smoothly. The overuse of antibiotics,our favorite pharmaceutical pest-control system,(75) often compromise healthy systemic function bydestroying healthful bacteria as well as harmfulones. For instance, humans with depleted levelsof Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum in their intestineshave higher rates of chronic bowel diseases like(80) ulcerative colitis and Crohns disease. Researchinto how these microorganisms has explodedin recent years, particularly regarding how theyinteract with human chemistry to regulate ourhormones, our blood sugar, and even our mood.*human-centered*species that live together in a mutually supportive relationship.Q.Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?a)Lines 13–14 (“The selective . . . intelligence”)b)Lines 17–20 (“They must . . . prey”)c)Lines 20–22 (“At . . . thieves”)d)Lines 26–29 (“Your pet . . . forebears”)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?.

Solutions for Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is from A. R. Kirchoff, “The New Ecosystems of the Anthropocene" ©2017 by College Hill Coaching.Scavengers—animals that feed on carcasses,rotting plants, or waste—get a bad rap.Yellowjackets and raccoons swarming aroundgarbage cans can seem like annoying pests at(5) best and germ-infested monsters at worst. Indeed,scavengers have been known to spread diseasessuch as meningitis, leptospirosis, and bubonicplague, so its no surprise that they are the focusof a huge extermination industry. But our habit of(10) eradicating irksome species ignores an importantfact: scavenger relationships are essential to allcomplex life.The selective pressures of scavenger behavioraccelerate the evolution of social intelligence.(15) For thousands of generations, some scavengerspecies have struggled to outwit the wily hunterswith whom they compete for scraps. Theymust predict, plan, and communicate as theyapproach a carcass in order to avoid becoming(20) the next prey. At the same time, hunters likeHomo sapiens had to become more clever toprotect their meat from these thieves. This socialinteraction has allowed at least one scavengerspecies to thrive in an anthropocentric* world:(25) Canis lupus familiaris—the domesticated dog.Your pet terrier would not be such a faithfulcompanion if its ancestor, the grey wolf, hadnot spend so much time picking over the trashof our hunter forebears. In just 20,000 years, we(30) have become symbionts,* turning a few lines ofwolves from freeloading foragers into friendlyFrisbee-fetchers.Even less perspicacious scavengers playa vital role in complex ecosystems, often in(35) unexpected ways. As plastic waste accumulatesrapidly in the ocean (and is expected to surpassthe total mass of fish by 2050), and toxicchemical waste continues to be dumped intoour water supplies, the role of one particular(40) class of scavenger, the decomposers, has becomecritical. These creatures break down complexmolecules into simpler ones in a process calledbiodegradation. Alcanivorax borkumensis, anaturally occurring marine bacterium, can(45) digest petroleum and convert it into foodenergy. Hydrocarbons like petroleum andplastics are energy-rich organic moleculesmuch like starches, fats, and proteins, sothe idea that they can be used as food by(50) opportunistic organisms is not so biochemicallyfar-fetched. After crude oil spills, cleanupcrews encourage this biodegradation by usingchemical dispersant to break the petroleuminto smaller droplets, thereby creating more(55) surface area for the bacteria to attack. Anotherdecomposer, Aspergillus tubingensis, is able togreatly accelerate the breakdown of polyesterpolyurethane, a petroleum product and one ofthe more durable plastics in our landfills and(60) oceans. Although environmentalists have yetto discover a practical method for harnessingA. tubingensis in large-scale waste mitigationsystems, such bio-technological solutions maynot be far off.(65) Our dependence on unicellular opportunistsgoes deeper still: our digestive processes,blood pressure, and immune system dependon thousands of species of scavenger bacteriathat live primarily in our gut and make up our(70) microbiome. These organisms patrol the intricatechemical pathways of the gut and perform dutiesthat, under normal circumstances, keep thingsrunning smoothly. The overuse of antibiotics,our favorite pharmaceutical pest-control system,(75) often compromise healthy systemic function bydestroying healthful bacteria as well as harmfulones. For instance, humans with depleted levelsof Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum in their intestineshave higher rates of chronic bowel diseases like(80) ulcerative colitis and Crohns disease. Researchinto how these microorganisms has explodedin recent years, particularly regarding how theyinteract with human chemistry to regulate ourhormones, our blood sugar, and even our mood.*human-centered*species that live together in a mutually supportive relationship.Q.Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?a)Lines 13–14 (“The selective . . . intelligence”)b)Lines 17–20 (“They must . . . prey”)c)Lines 20–22 (“At . . . thieves”)d)Lines 26–29 (“Your pet . . . forebears”)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? in English & in Hindi are available as part of our courses for SAT.

Download more important topics, notes, lectures and mock test series for SAT Exam by signing up for free.

Here you can find the meaning of Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is from A. R. Kirchoff, “The New Ecosystems of the Anthropocene" ©2017 by College Hill Coaching.Scavengers—animals that feed on carcasses,rotting plants, or waste—get a bad rap.Yellowjackets and raccoons swarming aroundgarbage cans can seem like annoying pests at(5) best and germ-infested monsters at worst. Indeed,scavengers have been known to spread diseasessuch as meningitis, leptospirosis, and bubonicplague, so its no surprise that they are the focusof a huge extermination industry. But our habit of(10) eradicating irksome species ignores an importantfact: scavenger relationships are essential to allcomplex life.The selective pressures of scavenger behavioraccelerate the evolution of social intelligence.(15) For thousands of generations, some scavengerspecies have struggled to outwit the wily hunterswith whom they compete for scraps. Theymust predict, plan, and communicate as theyapproach a carcass in order to avoid becoming(20) the next prey. At the same time, hunters likeHomo sapiens had to become more clever toprotect their meat from these thieves. This socialinteraction has allowed at least one scavengerspecies to thrive in an anthropocentric* world:(25) Canis lupus familiaris—the domesticated dog.Your pet terrier would not be such a faithfulcompanion if its ancestor, the grey wolf, hadnot spend so much time picking over the trashof our hunter forebears. In just 20,000 years, we(30) have become symbionts,* turning a few lines ofwolves from freeloading foragers into friendlyFrisbee-fetchers.Even less perspicacious scavengers playa vital role in complex ecosystems, often in(35) unexpected ways. As plastic waste accumulatesrapidly in the ocean (and is expected to surpassthe total mass of fish by 2050), and toxicchemical waste continues to be dumped intoour water supplies, the role of one particular(40) class of scavenger, the decomposers, has becomecritical. These creatures break down complexmolecules into simpler ones in a process calledbiodegradation. Alcanivorax borkumensis, anaturally occurring marine bacterium, can(45) digest petroleum and convert it into foodenergy. Hydrocarbons like petroleum andplastics are energy-rich organic moleculesmuch like starches, fats, and proteins, sothe idea that they can be used as food by(50) opportunistic organisms is not so biochemicallyfar-fetched. After crude oil spills, cleanupcrews encourage this biodegradation by usingchemical dispersant to break the petroleuminto smaller droplets, thereby creating more(55) surface area for the bacteria to attack. Anotherdecomposer, Aspergillus tubingensis, is able togreatly accelerate the breakdown of polyesterpolyurethane, a petroleum product and one ofthe more durable plastics in our landfills and(60) oceans. Although environmentalists have yetto discover a practical method for harnessingA. tubingensis in large-scale waste mitigationsystems, such bio-technological solutions maynot be far off.(65) Our dependence on unicellular opportunistsgoes deeper still: our digestive processes,blood pressure, and immune system dependon thousands of species of scavenger bacteriathat live primarily in our gut and make up our(70) microbiome. These organisms patrol the intricatechemical pathways of the gut and perform dutiesthat, under normal circumstances, keep thingsrunning smoothly. The overuse of antibiotics,our favorite pharmaceutical pest-control system,(75) often compromise healthy systemic function bydestroying healthful bacteria as well as harmfulones. For instance, humans with depleted levelsof Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum in their intestineshave higher rates of chronic bowel diseases like(80) ulcerative colitis and Crohns disease. Researchinto how these microorganisms has explodedin recent years, particularly regarding how theyinteract with human chemistry to regulate ourhormones, our blood sugar, and even our mood.*human-centered*species that live together in a mutually supportive relationship.Q.Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?a)Lines 13–14 (“The selective . . . intelligence”)b)Lines 17–20 (“They must . . . prey”)c)Lines 20–22 (“At . . . thieves”)d)Lines 26–29 (“Your pet . . . forebears”)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? defined & explained in the simplest way possible. Besides giving the explanation of

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is from A. R. Kirchoff, “The New Ecosystems of the Anthropocene" ©2017 by College Hill Coaching.Scavengers—animals that feed on carcasses,rotting plants, or waste—get a bad rap.Yellowjackets and raccoons swarming aroundgarbage cans can seem like annoying pests at(5) best and germ-infested monsters at worst. Indeed,scavengers have been known to spread diseasessuch as meningitis, leptospirosis, and bubonicplague, so its no surprise that they are the focusof a huge extermination industry. But our habit of(10) eradicating irksome species ignores an importantfact: scavenger relationships are essential to allcomplex life.The selective pressures of scavenger behavioraccelerate the evolution of social intelligence.(15) For thousands of generations, some scavengerspecies have struggled to outwit the wily hunterswith whom they compete for scraps. Theymust predict, plan, and communicate as theyapproach a carcass in order to avoid becoming(20) the next prey. At the same time, hunters likeHomo sapiens had to become more clever toprotect their meat from these thieves. This socialinteraction has allowed at least one scavengerspecies to thrive in an anthropocentric* world:(25) Canis lupus familiaris—the domesticated dog.Your pet terrier would not be such a faithfulcompanion if its ancestor, the grey wolf, hadnot spend so much time picking over the trashof our hunter forebears. In just 20,000 years, we(30) have become symbionts,* turning a few lines ofwolves from freeloading foragers into friendlyFrisbee-fetchers.Even less perspicacious scavengers playa vital role in complex ecosystems, often in(35) unexpected ways. As plastic waste accumulatesrapidly in the ocean (and is expected to surpassthe total mass of fish by 2050), and toxicchemical waste continues to be dumped intoour water supplies, the role of one particular(40) class of scavenger, the decomposers, has becomecritical. These creatures break down complexmolecules into simpler ones in a process calledbiodegradation. Alcanivorax borkumensis, anaturally occurring marine bacterium, can(45) digest petroleum and convert it into foodenergy. Hydrocarbons like petroleum andplastics are energy-rich organic moleculesmuch like starches, fats, and proteins, sothe idea that they can be used as food by(50) opportunistic organisms is not so biochemicallyfar-fetched. After crude oil spills, cleanupcrews encourage this biodegradation by usingchemical dispersant to break the petroleuminto smaller droplets, thereby creating more(55) surface area for the bacteria to attack. Anotherdecomposer, Aspergillus tubingensis, is able togreatly accelerate the breakdown of polyesterpolyurethane, a petroleum product and one ofthe more durable plastics in our landfills and(60) oceans. Although environmentalists have yetto discover a practical method for harnessingA. tubingensis in large-scale waste mitigationsystems, such bio-technological solutions maynot be far off.(65) Our dependence on unicellular opportunistsgoes deeper still: our digestive processes,blood pressure, and immune system dependon thousands of species of scavenger bacteriathat live primarily in our gut and make up our(70) microbiome. These organisms patrol the intricatechemical pathways of the gut and perform dutiesthat, under normal circumstances, keep thingsrunning smoothly. The overuse of antibiotics,our favorite pharmaceutical pest-control system,(75) often compromise healthy systemic function bydestroying healthful bacteria as well as harmfulones. For instance, humans with depleted levelsof Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum in their intestineshave higher rates of chronic bowel diseases like(80) ulcerative colitis and Crohns disease. Researchinto how these microorganisms has explodedin recent years, particularly regarding how theyinteract with human chemistry to regulate ourhormones, our blood sugar, and even our mood.*human-centered*species that live together in a mutually supportive relationship.Q.Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?a)Lines 13–14 (“The selective . . . intelligence”)b)Lines 17–20 (“They must . . . prey”)c)Lines 20–22 (“At . . . thieves”)d)Lines 26–29 (“Your pet . . . forebears”)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?, a detailed solution for Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is from A. R. Kirchoff, “The New Ecosystems of the Anthropocene" ©2017 by College Hill Coaching.Scavengers—animals that feed on carcasses,rotting plants, or waste—get a bad rap.Yellowjackets and raccoons swarming aroundgarbage cans can seem like annoying pests at(5) best and germ-infested monsters at worst. Indeed,scavengers have been known to spread diseasessuch as meningitis, leptospirosis, and bubonicplague, so its no surprise that they are the focusof a huge extermination industry. But our habit of(10) eradicating irksome species ignores an importantfact: scavenger relationships are essential to allcomplex life.The selective pressures of scavenger behavioraccelerate the evolution of social intelligence.(15) For thousands of generations, some scavengerspecies have struggled to outwit the wily hunterswith whom they compete for scraps. Theymust predict, plan, and communicate as theyapproach a carcass in order to avoid becoming(20) the next prey. At the same time, hunters likeHomo sapiens had to become more clever toprotect their meat from these thieves. This socialinteraction has allowed at least one scavengerspecies to thrive in an anthropocentric* world:(25) Canis lupus familiaris—the domesticated dog.Your pet terrier would not be such a faithfulcompanion if its ancestor, the grey wolf, hadnot spend so much time picking over the trashof our hunter forebears. In just 20,000 years, we(30) have become symbionts,* turning a few lines ofwolves from freeloading foragers into friendlyFrisbee-fetchers.Even less perspicacious scavengers playa vital role in complex ecosystems, often in(35) unexpected ways. As plastic waste accumulatesrapidly in the ocean (and is expected to surpassthe total mass of fish by 2050), and toxicchemical waste continues to be dumped intoour water supplies, the role of one particular(40) class of scavenger, the decomposers, has becomecritical. These creatures break down complexmolecules into simpler ones in a process calledbiodegradation. Alcanivorax borkumensis, anaturally occurring marine bacterium, can(45) digest petroleum and convert it into foodenergy. Hydrocarbons like petroleum andplastics are energy-rich organic moleculesmuch like starches, fats, and proteins, sothe idea that they can be used as food by(50) opportunistic organisms is not so biochemicallyfar-fetched. After crude oil spills, cleanupcrews encourage this biodegradation by usingchemical dispersant to break the petroleuminto smaller droplets, thereby creating more(55) surface area for the bacteria to attack. Anotherdecomposer, Aspergillus tubingensis, is able togreatly accelerate the breakdown of polyesterpolyurethane, a petroleum product and one ofthe more durable plastics in our landfills and(60) oceans. Although environmentalists have yetto discover a practical method for harnessingA. tubingensis in large-scale waste mitigationsystems, such bio-technological solutions maynot be far off.(65) Our dependence on unicellular opportunistsgoes deeper still: our digestive processes,blood pressure, and immune system dependon thousands of species of scavenger bacteriathat live primarily in our gut and make up our(70) microbiome. These organisms patrol the intricatechemical pathways of the gut and perform dutiesthat, under normal circumstances, keep thingsrunning smoothly. The overuse of antibiotics,our favorite pharmaceutical pest-control system,(75) often compromise healthy systemic function bydestroying healthful bacteria as well as harmfulones. For instance, humans with depleted levelsof Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum in their intestineshave higher rates of chronic bowel diseases like(80) ulcerative colitis and Crohns disease. Researchinto how these microorganisms has explodedin recent years, particularly regarding how theyinteract with human chemistry to regulate ourhormones, our blood sugar, and even our mood.*human-centered*species that live together in a mutually supportive relationship.Q.Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?a)Lines 13–14 (“The selective . . . intelligence”)b)Lines 17–20 (“They must . . . prey”)c)Lines 20–22 (“At . . . thieves”)d)Lines 26–29 (“Your pet . . . forebears”)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? has been provided alongside types of Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is from A. R. Kirchoff, “The New Ecosystems of the Anthropocene" ©2017 by College Hill Coaching.Scavengers—animals that feed on carcasses,rotting plants, or waste—get a bad rap.Yellowjackets and raccoons swarming aroundgarbage cans can seem like annoying pests at(5) best and germ-infested monsters at worst. Indeed,scavengers have been known to spread diseasessuch as meningitis, leptospirosis, and bubonicplague, so its no surprise that they are the focusof a huge extermination industry. But our habit of(10) eradicating irksome species ignores an importantfact: scavenger relationships are essential to allcomplex life.The selective pressures of scavenger behavioraccelerate the evolution of social intelligence.(15) For thousands of generations, some scavengerspecies have struggled to outwit the wily hunterswith whom they compete for scraps. Theymust predict, plan, and communicate as theyapproach a carcass in order to avoid becoming(20) the next prey. At the same time, hunters likeHomo sapiens had to become more clever toprotect their meat from these thieves. This socialinteraction has allowed at least one scavengerspecies to thrive in an anthropocentric* world:(25) Canis lupus familiaris—the domesticated dog.Your pet terrier would not be such a faithfulcompanion if its ancestor, the grey wolf, hadnot spend so much time picking over the trashof our hunter forebears. In just 20,000 years, we(30) have become symbionts,* turning a few lines ofwolves from freeloading foragers into friendlyFrisbee-fetchers.Even less perspicacious scavengers playa vital role in complex ecosystems, often in(35) unexpected ways. As plastic waste accumulatesrapidly in the ocean (and is expected to surpassthe total mass of fish by 2050), and toxicchemical waste continues to be dumped intoour water supplies, the role of one particular(40) class of scavenger, the decomposers, has becomecritical. These creatures break down complexmolecules into simpler ones in a process calledbiodegradation. Alcanivorax borkumensis, anaturally occurring marine bacterium, can(45) digest petroleum and convert it into foodenergy. Hydrocarbons like petroleum andplastics are energy-rich organic moleculesmuch like starches, fats, and proteins, sothe idea that they can be used as food by(50) opportunistic organisms is not so biochemicallyfar-fetched. After crude oil spills, cleanupcrews encourage this biodegradation by usingchemical dispersant to break the petroleuminto smaller droplets, thereby creating more(55) surface area for the bacteria to attack. Anotherdecomposer, Aspergillus tubingensis, is able togreatly accelerate the breakdown of polyesterpolyurethane, a petroleum product and one ofthe more durable plastics in our landfills and(60) oceans. Although environmentalists have yetto discover a practical method for harnessingA. tubingensis in large-scale waste mitigationsystems, such bio-technological solutions maynot be far off.(65) Our dependence on unicellular opportunistsgoes deeper still: our digestive processes,blood pressure, and immune system dependon thousands of species of scavenger bacteriathat live primarily in our gut and make up our(70) microbiome. These organisms patrol the intricatechemical pathways of the gut and perform dutiesthat, under normal circumstances, keep thingsrunning smoothly. The overuse of antibiotics,our favorite pharmaceutical pest-control system,(75) often compromise healthy systemic function bydestroying healthful bacteria as well as harmfulones. For instance, humans with depleted levelsof Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum in their intestineshave higher rates of chronic bowel diseases like(80) ulcerative colitis and Crohns disease. Researchinto how these microorganisms has explodedin recent years, particularly regarding how theyinteract with human chemistry to regulate ourhormones, our blood sugar, and even our mood.*human-centered*species that live together in a mutually supportive relationship.Q.Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?a)Lines 13–14 (“The selective . . . intelligence”)b)Lines 17–20 (“They must . . . prey”)c)Lines 20–22 (“At . . . thieves”)d)Lines 26–29 (“Your pet . . . forebears”)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? theory, EduRev gives you an

ample number of questions to practice Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.This passage is from A. R. Kirchoff, “The New Ecosystems of the Anthropocene" ©2017 by College Hill Coaching.Scavengers—animals that feed on carcasses,rotting plants, or waste—get a bad rap.Yellowjackets and raccoons swarming aroundgarbage cans can seem like annoying pests at(5) best and germ-infested monsters at worst. Indeed,scavengers have been known to spread diseasessuch as meningitis, leptospirosis, and bubonicplague, so its no surprise that they are the focusof a huge extermination industry. But our habit of(10) eradicating irksome species ignores an importantfact: scavenger relationships are essential to allcomplex life.The selective pressures of scavenger behavioraccelerate the evolution of social intelligence.(15) For thousands of generations, some scavengerspecies have struggled to outwit the wily hunterswith whom they compete for scraps. Theymust predict, plan, and communicate as theyapproach a carcass in order to avoid becoming(20) the next prey. At the same time, hunters likeHomo sapiens had to become more clever toprotect their meat from these thieves. This socialinteraction has allowed at least one scavengerspecies to thrive in an anthropocentric* world:(25) Canis lupus familiaris—the domesticated dog.Your pet terrier would not be such a faithfulcompanion if its ancestor, the grey wolf, hadnot spend so much time picking over the trashof our hunter forebears. In just 20,000 years, we(30) have become symbionts,* turning a few lines ofwolves from freeloading foragers into friendlyFrisbee-fetchers.Even less perspicacious scavengers playa vital role in complex ecosystems, often in(35) unexpected ways. As plastic waste accumulatesrapidly in the ocean (and is expected to surpassthe total mass of fish by 2050), and toxicchemical waste continues to be dumped intoour water supplies, the role of one particular(40) class of scavenger, the decomposers, has becomecritical. These creatures break down complexmolecules into simpler ones in a process calledbiodegradation. Alcanivorax borkumensis, anaturally occurring marine bacterium, can(45) digest petroleum and convert it into foodenergy. Hydrocarbons like petroleum andplastics are energy-rich organic moleculesmuch like starches, fats, and proteins, sothe idea that they can be used as food by(50) opportunistic organisms is not so biochemicallyfar-fetched. After crude oil spills, cleanupcrews encourage this biodegradation by usingchemical dispersant to break the petroleuminto smaller droplets, thereby creating more(55) surface area for the bacteria to attack. Anotherdecomposer, Aspergillus tubingensis, is able togreatly accelerate the breakdown of polyesterpolyurethane, a petroleum product and one ofthe more durable plastics in our landfills and(60) oceans. Although environmentalists have yetto discover a practical method for harnessingA. tubingensis in large-scale waste mitigationsystems, such bio-technological solutions maynot be far off.(65) Our dependence on unicellular opportunistsgoes deeper still: our digestive processes,blood pressure, and immune system dependon thousands of species of scavenger bacteriathat live primarily in our gut and make up our(70) microbiome. These organisms patrol the intricatechemical pathways of the gut and perform dutiesthat, under normal circumstances, keep thingsrunning smoothly. The overuse of antibiotics,our favorite pharmaceutical pest-control system,(75) often compromise healthy systemic function bydestroying healthful bacteria as well as harmfulones. For instance, humans with depleted levelsof Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum in their intestineshave higher rates of chronic bowel diseases like(80) ulcerative colitis and Crohns disease. Researchinto how these microorganisms has explodedin recent years, particularly regarding how theyinteract with human chemistry to regulate ourhormones, our blood sugar, and even our mood.*human-centered*species that live together in a mutually supportive relationship.Q.Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?a)Lines 13–14 (“The selective . . . intelligence”)b)Lines 17–20 (“They must . . . prey”)c)Lines 20–22 (“At . . . thieves”)d)Lines 26–29 (“Your pet . . . forebears”)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? tests, examples and also practice SAT tests.

|

Explore Courses for SAT exam

|

|

Signup for Free!

Signup to see your scores go up within 7 days! Learn & Practice with 1000+ FREE Notes, Videos & Tests.