SAT Exam > SAT Questions > Question based on the following passages and ...

Start Learning for Free

Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.

The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.

As traffic levels in the United States decline in

defiance of forecasts projecting major increases, a

number of commentators have claimed that we've

reached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in

(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comes

to an end. But while this has been celebrated by

many urbanists as undermining plans for more

roads, we have yet to face the implications peak

car has for public policy.

(10) For a long time, urbanists have embraced

Say's Law of Markets for roads: increasing the

supply of driving lanes only increases the number

of drivers to fill them, hence building more roads

to reduce congestion is pointless. But if we've

(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really can

build our way out of congestion after all.

Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallen

in recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked on

a per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.

(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994

levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travel

shows a marked reversal.

These data are complemented by a slew of

recent stories about the poor financial

(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in part

from traffic falling far below projections. On the

Indiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% in

eight years, in contrast with a forecasted increase

of 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.

(30) Many of the trends that drove high traffic

growth in the past have largely been played

out: household size declines, suburbanization,

the entry of women into the workforce, one

car per driver, etc. That's not to say these will

(35) necessarily reverse. But we've reached the point

of diminishing returns, particularly in terms of

how many more women will join the labor force.

This is potentially very good fiscal news,

especially given tight budgets. Clearly many

(40) freeway expansion projects that have been driven

by speculative demand should be revisited. From

top to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate their

forecasting models to better correspond to reality,

and then revisit highway plans accordingly.

(45) But we must also pay attention to the flip

side of peak car. Although speculative highway

expansion projects may be dubious, there may be

good reasons now to build projects designed to

alleviate already exiting congestion. Places like

(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, which

has great economic and social consequences,

not the least of which is the value of untold hours

lost sitting in traffic. Although some projects

there might indeed be boondoggles, maybe it's

(55) worth building some of the planned freeway

expansions there in light of peak car. In short,

in some cases—particularly where Say's Law no

longer seems to apply—peak car strengthens the

argument for building or expanding roads.

(60) On the other hand, many of the regional

development plans designed to promote compact

central city development and transit may be

predicated on an analysis that assumes large

future traffic increases in a “business as usual”

(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects of

regional planning are dependent on traffic

forecasts. That's not to say that such plans are

necessarily wrong, but clearly revised traffic

reality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just

(70) highway building ones.

Urbanists and policy makers of all stripes

need to think about the full implications of peak

car. At a minimum, the traditional “you can't

build your way out of congestion” rhetoric should

(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a more

nuanced approach that neither overestimates

demand, nor ignores the problems caused by

rapid growth in some regions and pockets of

congestion in others.

The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.

As traffic levels in the United States decline in

defiance of forecasts projecting major increases, a

number of commentators have claimed that we've

reached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in

(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comes

to an end. But while this has been celebrated by

many urbanists as undermining plans for more

roads, we have yet to face the implications peak

car has for public policy.

(10) For a long time, urbanists have embraced

Say's Law of Markets for roads: increasing the

supply of driving lanes only increases the number

of drivers to fill them, hence building more roads

to reduce congestion is pointless. But if we've

(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really can

build our way out of congestion after all.

Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallen

in recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked on

a per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.

(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994

levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travel

shows a marked reversal.

These data are complemented by a slew of

recent stories about the poor financial

(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in part

from traffic falling far below projections. On the

Indiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% in

eight years, in contrast with a forecasted increase

of 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.

(30) Many of the trends that drove high traffic

growth in the past have largely been played

out: household size declines, suburbanization,

the entry of women into the workforce, one

car per driver, etc. That's not to say these will

(35) necessarily reverse. But we've reached the point

of diminishing returns, particularly in terms of

how many more women will join the labor force.

This is potentially very good fiscal news,

especially given tight budgets. Clearly many

(40) freeway expansion projects that have been driven

by speculative demand should be revisited. From

top to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate their

forecasting models to better correspond to reality,

and then revisit highway plans accordingly.

(45) But we must also pay attention to the flip

side of peak car. Although speculative highway

expansion projects may be dubious, there may be

good reasons now to build projects designed to

alleviate already exiting congestion. Places like

(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, which

has great economic and social consequences,

not the least of which is the value of untold hours

lost sitting in traffic. Although some projects

there might indeed be boondoggles, maybe it's

(55) worth building some of the planned freeway

expansions there in light of peak car. In short,

in some cases—particularly where Say's Law no

longer seems to apply—peak car strengthens the

argument for building or expanding roads.

(60) On the other hand, many of the regional

development plans designed to promote compact

central city development and transit may be

predicated on an analysis that assumes large

future traffic increases in a “business as usual”

(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects of

regional planning are dependent on traffic

forecasts. That's not to say that such plans are

necessarily wrong, but clearly revised traffic

reality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just

(70) highway building ones.

Urbanists and policy makers of all stripes

need to think about the full implications of peak

car. At a minimum, the traditional “you can't

build your way out of congestion” rhetoric should

(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a more

nuanced approach that neither overestimates

demand, nor ignores the problems caused by

rapid growth in some regions and pockets of

congestion in others.

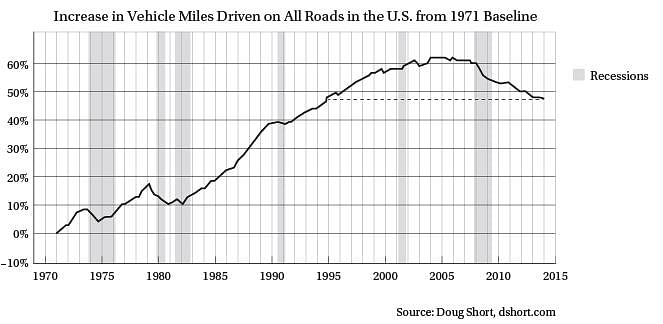

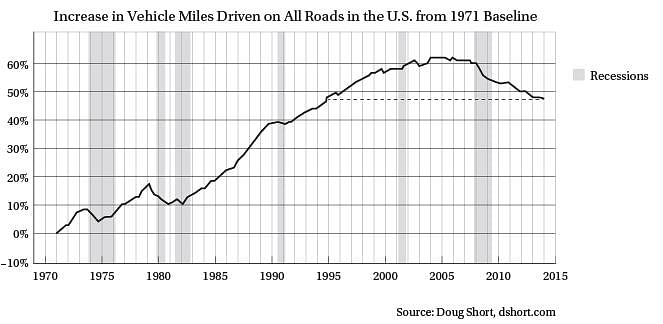

Q. The graph best supports which claim about the relationship between economic recessions in the U.S. and total vehicle miles driven on U.S. roads?

- a)In the last four decades, recessions that last longer than a year correspond to a decrease in total vehicle miles.

- b)The six most recent recession periods each corresponded to an increase in total vehicle miles.

- c)Recent recessions in the U.S. do not correlate strongly with either an increase or decrease in total vehicle miles.

- d)In the last four decades, the longer a recession lasts, the more dramatically total vehicle miles decline.

Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer?

Verified Answer

Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.Th...

In the graph, periods of recession are indicated by vertical gray bars. In the six recessions shown, three seem to correspond to a decrease in vehicle miles and three seem to correspond to an increase in vehicle miles. Therefore, it is safe to say that this graph does not support any claim about a strong correlation between recessions and total vehicle miles.

|

Explore Courses for SAT exam

|

|

Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.As traffic levels in the United States decline indefiance of forecasts projecting major increases, anumber of commentators have claimed that wevereached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comesto an end. But while this has been celebrated bymany urbanists as undermining plans for moreroads, we have yet to face the implications peakcar has for public policy.(10) For a long time, urbanists have embracedSays Law of Markets for roads: increasing thesupply of driving lanes only increases the numberof drivers to fill them, hence building more roadsto reduce congestion is pointless. But if weve(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really canbuild our way out of congestion after all.Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallenin recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked ona per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travelshows a marked reversal.These data are complemented by a slew ofrecent stories about the poor financial(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in partfrom traffic falling far below projections. On theIndiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% ineight years, in contrast with a forecasted increaseof 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.(30) Many of the trends that drove high trafficgrowth in the past have largely been playedout: household size declines, suburbanization,the entry of women into the workforce, onecar per driver, etc. Thats not to say these will(35) necessarily reverse. But weve reached the pointof diminishing returns, particularly in terms ofhow many more women will join the labor force.This is potentially very good fiscal news,especially given tight budgets. Clearly many(40) freeway expansion projects that have been drivenby speculative demand should be revisited. Fromtop to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate theirforecasting models to better correspond to reality,and then revisit highway plans accordingly.(45)But we must also pay attention to the flipside of peak car. Although speculative highwayexpansion projects may be dubious, there may begood reasons now to build projects designed toalleviate already exiting congestion. Places like(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, whichhas great economic and social consequences,not the least of which is the value of untold hourslost sitting in traffic. Although some projectsthere might indeed be boondoggles, maybe its(55) worth building some of the planned freewayexpansions there in light of peak car. In short,in some cases—particularly where Says Law nolonger seems to apply—peak car strengthens theargument for building or expanding roads.(60) On the other hand, many of the regionaldevelopment plans designed to promote compactcentral city development and transit may bepredicated on an analysis that assumes largefuture traffic increases in a “business as usual”(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects ofregional planning are dependent on trafficforecasts. Thats not to say that such plans arenecessarily wrong, but clearly revised trafficreality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just(70) highway building ones.Urbanists and policy makers of all stripesneed to think about the full implications of peakcar. At a minimum, the traditional “you cantbuild your way out of congestion” rhetoric should(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a morenuanced approach that neither overestimatesdemand, nor ignores the problems caused byrapid growth in some regions and pockets ofcongestion in others.Q.The graph best supports which claim about the relationship between economic recessions in the U.S. and total vehicle miles driven on U.S. roads?a)In the last four decades, recessions that last longer than a year correspond to a decrease in total vehicle miles.b)The six most recent recession periods each corresponded to an increase in total vehicle miles.c)Recent recessions in the U.S. do not correlate strongly with either an increase or decrease in total vehicle miles.d)In the last four decades, the longer a recession lasts, the more dramatically total vehicle miles decline.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer?

Question Description

Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.As traffic levels in the United States decline indefiance of forecasts projecting major increases, anumber of commentators have claimed that wevereached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comesto an end. But while this has been celebrated bymany urbanists as undermining plans for moreroads, we have yet to face the implications peakcar has for public policy.(10) For a long time, urbanists have embracedSays Law of Markets for roads: increasing thesupply of driving lanes only increases the numberof drivers to fill them, hence building more roadsto reduce congestion is pointless. But if weve(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really canbuild our way out of congestion after all.Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallenin recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked ona per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travelshows a marked reversal.These data are complemented by a slew ofrecent stories about the poor financial(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in partfrom traffic falling far below projections. On theIndiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% ineight years, in contrast with a forecasted increaseof 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.(30) Many of the trends that drove high trafficgrowth in the past have largely been playedout: household size declines, suburbanization,the entry of women into the workforce, onecar per driver, etc. Thats not to say these will(35) necessarily reverse. But weve reached the pointof diminishing returns, particularly in terms ofhow many more women will join the labor force.This is potentially very good fiscal news,especially given tight budgets. Clearly many(40) freeway expansion projects that have been drivenby speculative demand should be revisited. Fromtop to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate theirforecasting models to better correspond to reality,and then revisit highway plans accordingly.(45)But we must also pay attention to the flipside of peak car. Although speculative highwayexpansion projects may be dubious, there may begood reasons now to build projects designed toalleviate already exiting congestion. Places like(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, whichhas great economic and social consequences,not the least of which is the value of untold hourslost sitting in traffic. Although some projectsthere might indeed be boondoggles, maybe its(55) worth building some of the planned freewayexpansions there in light of peak car. In short,in some cases—particularly where Says Law nolonger seems to apply—peak car strengthens theargument for building or expanding roads.(60) On the other hand, many of the regionaldevelopment plans designed to promote compactcentral city development and transit may bepredicated on an analysis that assumes largefuture traffic increases in a “business as usual”(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects ofregional planning are dependent on trafficforecasts. Thats not to say that such plans arenecessarily wrong, but clearly revised trafficreality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just(70) highway building ones.Urbanists and policy makers of all stripesneed to think about the full implications of peakcar. At a minimum, the traditional “you cantbuild your way out of congestion” rhetoric should(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a morenuanced approach that neither overestimatesdemand, nor ignores the problems caused byrapid growth in some regions and pockets ofcongestion in others.Q.The graph best supports which claim about the relationship between economic recessions in the U.S. and total vehicle miles driven on U.S. roads?a)In the last four decades, recessions that last longer than a year correspond to a decrease in total vehicle miles.b)The six most recent recession periods each corresponded to an increase in total vehicle miles.c)Recent recessions in the U.S. do not correlate strongly with either an increase or decrease in total vehicle miles.d)In the last four decades, the longer a recession lasts, the more dramatically total vehicle miles decline.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? for SAT 2025 is part of SAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the SAT exam syllabus. Information about Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.As traffic levels in the United States decline indefiance of forecasts projecting major increases, anumber of commentators have claimed that wevereached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comesto an end. But while this has been celebrated bymany urbanists as undermining plans for moreroads, we have yet to face the implications peakcar has for public policy.(10) For a long time, urbanists have embracedSays Law of Markets for roads: increasing thesupply of driving lanes only increases the numberof drivers to fill them, hence building more roadsto reduce congestion is pointless. But if weve(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really canbuild our way out of congestion after all.Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallenin recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked ona per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travelshows a marked reversal.These data are complemented by a slew ofrecent stories about the poor financial(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in partfrom traffic falling far below projections. On theIndiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% ineight years, in contrast with a forecasted increaseof 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.(30) Many of the trends that drove high trafficgrowth in the past have largely been playedout: household size declines, suburbanization,the entry of women into the workforce, onecar per driver, etc. Thats not to say these will(35) necessarily reverse. But weve reached the pointof diminishing returns, particularly in terms ofhow many more women will join the labor force.This is potentially very good fiscal news,especially given tight budgets. Clearly many(40) freeway expansion projects that have been drivenby speculative demand should be revisited. Fromtop to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate theirforecasting models to better correspond to reality,and then revisit highway plans accordingly.(45)But we must also pay attention to the flipside of peak car. Although speculative highwayexpansion projects may be dubious, there may begood reasons now to build projects designed toalleviate already exiting congestion. Places like(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, whichhas great economic and social consequences,not the least of which is the value of untold hourslost sitting in traffic. Although some projectsthere might indeed be boondoggles, maybe its(55) worth building some of the planned freewayexpansions there in light of peak car. In short,in some cases—particularly where Says Law nolonger seems to apply—peak car strengthens theargument for building or expanding roads.(60) On the other hand, many of the regionaldevelopment plans designed to promote compactcentral city development and transit may bepredicated on an analysis that assumes largefuture traffic increases in a “business as usual”(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects ofregional planning are dependent on trafficforecasts. Thats not to say that such plans arenecessarily wrong, but clearly revised trafficreality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just(70) highway building ones.Urbanists and policy makers of all stripesneed to think about the full implications of peakcar. At a minimum, the traditional “you cantbuild your way out of congestion” rhetoric should(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a morenuanced approach that neither overestimatesdemand, nor ignores the problems caused byrapid growth in some regions and pockets ofcongestion in others.Q.The graph best supports which claim about the relationship between economic recessions in the U.S. and total vehicle miles driven on U.S. roads?a)In the last four decades, recessions that last longer than a year correspond to a decrease in total vehicle miles.b)The six most recent recession periods each corresponded to an increase in total vehicle miles.c)Recent recessions in the U.S. do not correlate strongly with either an increase or decrease in total vehicle miles.d)In the last four decades, the longer a recession lasts, the more dramatically total vehicle miles decline.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for SAT 2025 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.As traffic levels in the United States decline indefiance of forecasts projecting major increases, anumber of commentators have claimed that wevereached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comesto an end. But while this has been celebrated bymany urbanists as undermining plans for moreroads, we have yet to face the implications peakcar has for public policy.(10) For a long time, urbanists have embracedSays Law of Markets for roads: increasing thesupply of driving lanes only increases the numberof drivers to fill them, hence building more roadsto reduce congestion is pointless. But if weve(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really canbuild our way out of congestion after all.Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallenin recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked ona per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travelshows a marked reversal.These data are complemented by a slew ofrecent stories about the poor financial(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in partfrom traffic falling far below projections. On theIndiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% ineight years, in contrast with a forecasted increaseof 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.(30) Many of the trends that drove high trafficgrowth in the past have largely been playedout: household size declines, suburbanization,the entry of women into the workforce, onecar per driver, etc. Thats not to say these will(35) necessarily reverse. But weve reached the pointof diminishing returns, particularly in terms ofhow many more women will join the labor force.This is potentially very good fiscal news,especially given tight budgets. Clearly many(40) freeway expansion projects that have been drivenby speculative demand should be revisited. Fromtop to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate theirforecasting models to better correspond to reality,and then revisit highway plans accordingly.(45)But we must also pay attention to the flipside of peak car. Although speculative highwayexpansion projects may be dubious, there may begood reasons now to build projects designed toalleviate already exiting congestion. Places like(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, whichhas great economic and social consequences,not the least of which is the value of untold hourslost sitting in traffic. Although some projectsthere might indeed be boondoggles, maybe its(55) worth building some of the planned freewayexpansions there in light of peak car. In short,in some cases—particularly where Says Law nolonger seems to apply—peak car strengthens theargument for building or expanding roads.(60) On the other hand, many of the regionaldevelopment plans designed to promote compactcentral city development and transit may bepredicated on an analysis that assumes largefuture traffic increases in a “business as usual”(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects ofregional planning are dependent on trafficforecasts. Thats not to say that such plans arenecessarily wrong, but clearly revised trafficreality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just(70) highway building ones.Urbanists and policy makers of all stripesneed to think about the full implications of peakcar. At a minimum, the traditional “you cantbuild your way out of congestion” rhetoric should(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a morenuanced approach that neither overestimatesdemand, nor ignores the problems caused byrapid growth in some regions and pockets ofcongestion in others.Q.The graph best supports which claim about the relationship between economic recessions in the U.S. and total vehicle miles driven on U.S. roads?a)In the last four decades, recessions that last longer than a year correspond to a decrease in total vehicle miles.b)The six most recent recession periods each corresponded to an increase in total vehicle miles.c)Recent recessions in the U.S. do not correlate strongly with either an increase or decrease in total vehicle miles.d)In the last four decades, the longer a recession lasts, the more dramatically total vehicle miles decline.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer?.

Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.As traffic levels in the United States decline indefiance of forecasts projecting major increases, anumber of commentators have claimed that wevereached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comesto an end. But while this has been celebrated bymany urbanists as undermining plans for moreroads, we have yet to face the implications peakcar has for public policy.(10) For a long time, urbanists have embracedSays Law of Markets for roads: increasing thesupply of driving lanes only increases the numberof drivers to fill them, hence building more roadsto reduce congestion is pointless. But if weve(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really canbuild our way out of congestion after all.Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallenin recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked ona per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travelshows a marked reversal.These data are complemented by a slew ofrecent stories about the poor financial(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in partfrom traffic falling far below projections. On theIndiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% ineight years, in contrast with a forecasted increaseof 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.(30) Many of the trends that drove high trafficgrowth in the past have largely been playedout: household size declines, suburbanization,the entry of women into the workforce, onecar per driver, etc. Thats not to say these will(35) necessarily reverse. But weve reached the pointof diminishing returns, particularly in terms ofhow many more women will join the labor force.This is potentially very good fiscal news,especially given tight budgets. Clearly many(40) freeway expansion projects that have been drivenby speculative demand should be revisited. Fromtop to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate theirforecasting models to better correspond to reality,and then revisit highway plans accordingly.(45)But we must also pay attention to the flipside of peak car. Although speculative highwayexpansion projects may be dubious, there may begood reasons now to build projects designed toalleviate already exiting congestion. Places like(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, whichhas great economic and social consequences,not the least of which is the value of untold hourslost sitting in traffic. Although some projectsthere might indeed be boondoggles, maybe its(55) worth building some of the planned freewayexpansions there in light of peak car. In short,in some cases—particularly where Says Law nolonger seems to apply—peak car strengthens theargument for building or expanding roads.(60) On the other hand, many of the regionaldevelopment plans designed to promote compactcentral city development and transit may bepredicated on an analysis that assumes largefuture traffic increases in a “business as usual”(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects ofregional planning are dependent on trafficforecasts. Thats not to say that such plans arenecessarily wrong, but clearly revised trafficreality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just(70) highway building ones.Urbanists and policy makers of all stripesneed to think about the full implications of peakcar. At a minimum, the traditional “you cantbuild your way out of congestion” rhetoric should(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a morenuanced approach that neither overestimatesdemand, nor ignores the problems caused byrapid growth in some regions and pockets ofcongestion in others.Q.The graph best supports which claim about the relationship between economic recessions in the U.S. and total vehicle miles driven on U.S. roads?a)In the last four decades, recessions that last longer than a year correspond to a decrease in total vehicle miles.b)The six most recent recession periods each corresponded to an increase in total vehicle miles.c)Recent recessions in the U.S. do not correlate strongly with either an increase or decrease in total vehicle miles.d)In the last four decades, the longer a recession lasts, the more dramatically total vehicle miles decline.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? for SAT 2025 is part of SAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the SAT exam syllabus. Information about Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.As traffic levels in the United States decline indefiance of forecasts projecting major increases, anumber of commentators have claimed that wevereached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comesto an end. But while this has been celebrated bymany urbanists as undermining plans for moreroads, we have yet to face the implications peakcar has for public policy.(10) For a long time, urbanists have embracedSays Law of Markets for roads: increasing thesupply of driving lanes only increases the numberof drivers to fill them, hence building more roadsto reduce congestion is pointless. But if weve(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really canbuild our way out of congestion after all.Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallenin recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked ona per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travelshows a marked reversal.These data are complemented by a slew ofrecent stories about the poor financial(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in partfrom traffic falling far below projections. On theIndiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% ineight years, in contrast with a forecasted increaseof 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.(30) Many of the trends that drove high trafficgrowth in the past have largely been playedout: household size declines, suburbanization,the entry of women into the workforce, onecar per driver, etc. Thats not to say these will(35) necessarily reverse. But weve reached the pointof diminishing returns, particularly in terms ofhow many more women will join the labor force.This is potentially very good fiscal news,especially given tight budgets. Clearly many(40) freeway expansion projects that have been drivenby speculative demand should be revisited. Fromtop to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate theirforecasting models to better correspond to reality,and then revisit highway plans accordingly.(45)But we must also pay attention to the flipside of peak car. Although speculative highwayexpansion projects may be dubious, there may begood reasons now to build projects designed toalleviate already exiting congestion. Places like(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, whichhas great economic and social consequences,not the least of which is the value of untold hourslost sitting in traffic. Although some projectsthere might indeed be boondoggles, maybe its(55) worth building some of the planned freewayexpansions there in light of peak car. In short,in some cases—particularly where Says Law nolonger seems to apply—peak car strengthens theargument for building or expanding roads.(60) On the other hand, many of the regionaldevelopment plans designed to promote compactcentral city development and transit may bepredicated on an analysis that assumes largefuture traffic increases in a “business as usual”(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects ofregional planning are dependent on trafficforecasts. Thats not to say that such plans arenecessarily wrong, but clearly revised trafficreality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just(70) highway building ones.Urbanists and policy makers of all stripesneed to think about the full implications of peakcar. At a minimum, the traditional “you cantbuild your way out of congestion” rhetoric should(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a morenuanced approach that neither overestimatesdemand, nor ignores the problems caused byrapid growth in some regions and pockets ofcongestion in others.Q.The graph best supports which claim about the relationship between economic recessions in the U.S. and total vehicle miles driven on U.S. roads?a)In the last four decades, recessions that last longer than a year correspond to a decrease in total vehicle miles.b)The six most recent recession periods each corresponded to an increase in total vehicle miles.c)Recent recessions in the U.S. do not correlate strongly with either an increase or decrease in total vehicle miles.d)In the last four decades, the longer a recession lasts, the more dramatically total vehicle miles decline.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for SAT 2025 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.As traffic levels in the United States decline indefiance of forecasts projecting major increases, anumber of commentators have claimed that wevereached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comesto an end. But while this has been celebrated bymany urbanists as undermining plans for moreroads, we have yet to face the implications peakcar has for public policy.(10) For a long time, urbanists have embracedSays Law of Markets for roads: increasing thesupply of driving lanes only increases the numberof drivers to fill them, hence building more roadsto reduce congestion is pointless. But if weve(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really canbuild our way out of congestion after all.Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallenin recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked ona per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travelshows a marked reversal.These data are complemented by a slew ofrecent stories about the poor financial(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in partfrom traffic falling far below projections. On theIndiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% ineight years, in contrast with a forecasted increaseof 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.(30) Many of the trends that drove high trafficgrowth in the past have largely been playedout: household size declines, suburbanization,the entry of women into the workforce, onecar per driver, etc. Thats not to say these will(35) necessarily reverse. But weve reached the pointof diminishing returns, particularly in terms ofhow many more women will join the labor force.This is potentially very good fiscal news,especially given tight budgets. Clearly many(40) freeway expansion projects that have been drivenby speculative demand should be revisited. Fromtop to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate theirforecasting models to better correspond to reality,and then revisit highway plans accordingly.(45)But we must also pay attention to the flipside of peak car. Although speculative highwayexpansion projects may be dubious, there may begood reasons now to build projects designed toalleviate already exiting congestion. Places like(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, whichhas great economic and social consequences,not the least of which is the value of untold hourslost sitting in traffic. Although some projectsthere might indeed be boondoggles, maybe its(55) worth building some of the planned freewayexpansions there in light of peak car. In short,in some cases—particularly where Says Law nolonger seems to apply—peak car strengthens theargument for building or expanding roads.(60) On the other hand, many of the regionaldevelopment plans designed to promote compactcentral city development and transit may bepredicated on an analysis that assumes largefuture traffic increases in a “business as usual”(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects ofregional planning are dependent on trafficforecasts. Thats not to say that such plans arenecessarily wrong, but clearly revised trafficreality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just(70) highway building ones.Urbanists and policy makers of all stripesneed to think about the full implications of peakcar. At a minimum, the traditional “you cantbuild your way out of congestion” rhetoric should(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a morenuanced approach that neither overestimatesdemand, nor ignores the problems caused byrapid growth in some regions and pockets ofcongestion in others.Q.The graph best supports which claim about the relationship between economic recessions in the U.S. and total vehicle miles driven on U.S. roads?a)In the last four decades, recessions that last longer than a year correspond to a decrease in total vehicle miles.b)The six most recent recession periods each corresponded to an increase in total vehicle miles.c)Recent recessions in the U.S. do not correlate strongly with either an increase or decrease in total vehicle miles.d)In the last four decades, the longer a recession lasts, the more dramatically total vehicle miles decline.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer?.

Solutions for Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.As traffic levels in the United States decline indefiance of forecasts projecting major increases, anumber of commentators have claimed that wevereached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comesto an end. But while this has been celebrated bymany urbanists as undermining plans for moreroads, we have yet to face the implications peakcar has for public policy.(10) For a long time, urbanists have embracedSays Law of Markets for roads: increasing thesupply of driving lanes only increases the numberof drivers to fill them, hence building more roadsto reduce congestion is pointless. But if weve(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really canbuild our way out of congestion after all.Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallenin recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked ona per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travelshows a marked reversal.These data are complemented by a slew ofrecent stories about the poor financial(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in partfrom traffic falling far below projections. On theIndiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% ineight years, in contrast with a forecasted increaseof 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.(30) Many of the trends that drove high trafficgrowth in the past have largely been playedout: household size declines, suburbanization,the entry of women into the workforce, onecar per driver, etc. Thats not to say these will(35) necessarily reverse. But weve reached the pointof diminishing returns, particularly in terms ofhow many more women will join the labor force.This is potentially very good fiscal news,especially given tight budgets. Clearly many(40) freeway expansion projects that have been drivenby speculative demand should be revisited. Fromtop to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate theirforecasting models to better correspond to reality,and then revisit highway plans accordingly.(45)But we must also pay attention to the flipside of peak car. Although speculative highwayexpansion projects may be dubious, there may begood reasons now to build projects designed toalleviate already exiting congestion. Places like(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, whichhas great economic and social consequences,not the least of which is the value of untold hourslost sitting in traffic. Although some projectsthere might indeed be boondoggles, maybe its(55) worth building some of the planned freewayexpansions there in light of peak car. In short,in some cases—particularly where Says Law nolonger seems to apply—peak car strengthens theargument for building or expanding roads.(60) On the other hand, many of the regionaldevelopment plans designed to promote compactcentral city development and transit may bepredicated on an analysis that assumes largefuture traffic increases in a “business as usual”(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects ofregional planning are dependent on trafficforecasts. Thats not to say that such plans arenecessarily wrong, but clearly revised trafficreality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just(70) highway building ones.Urbanists and policy makers of all stripesneed to think about the full implications of peakcar. At a minimum, the traditional “you cantbuild your way out of congestion” rhetoric should(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a morenuanced approach that neither overestimatesdemand, nor ignores the problems caused byrapid growth in some regions and pockets ofcongestion in others.Q.The graph best supports which claim about the relationship between economic recessions in the U.S. and total vehicle miles driven on U.S. roads?a)In the last four decades, recessions that last longer than a year correspond to a decrease in total vehicle miles.b)The six most recent recession periods each corresponded to an increase in total vehicle miles.c)Recent recessions in the U.S. do not correlate strongly with either an increase or decrease in total vehicle miles.d)In the last four decades, the longer a recession lasts, the more dramatically total vehicle miles decline.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? in English & in Hindi are available as part of our courses for SAT.

Download more important topics, notes, lectures and mock test series for SAT Exam by signing up for free.

Here you can find the meaning of Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.As traffic levels in the United States decline indefiance of forecasts projecting major increases, anumber of commentators have claimed that wevereached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comesto an end. But while this has been celebrated bymany urbanists as undermining plans for moreroads, we have yet to face the implications peakcar has for public policy.(10) For a long time, urbanists have embracedSays Law of Markets for roads: increasing thesupply of driving lanes only increases the numberof drivers to fill them, hence building more roadsto reduce congestion is pointless. But if weve(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really canbuild our way out of congestion after all.Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallenin recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked ona per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travelshows a marked reversal.These data are complemented by a slew ofrecent stories about the poor financial(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in partfrom traffic falling far below projections. On theIndiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% ineight years, in contrast with a forecasted increaseof 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.(30) Many of the trends that drove high trafficgrowth in the past have largely been playedout: household size declines, suburbanization,the entry of women into the workforce, onecar per driver, etc. Thats not to say these will(35) necessarily reverse. But weve reached the pointof diminishing returns, particularly in terms ofhow many more women will join the labor force.This is potentially very good fiscal news,especially given tight budgets. Clearly many(40) freeway expansion projects that have been drivenby speculative demand should be revisited. Fromtop to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate theirforecasting models to better correspond to reality,and then revisit highway plans accordingly.(45)But we must also pay attention to the flipside of peak car. Although speculative highwayexpansion projects may be dubious, there may begood reasons now to build projects designed toalleviate already exiting congestion. Places like(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, whichhas great economic and social consequences,not the least of which is the value of untold hourslost sitting in traffic. Although some projectsthere might indeed be boondoggles, maybe its(55) worth building some of the planned freewayexpansions there in light of peak car. In short,in some cases—particularly where Says Law nolonger seems to apply—peak car strengthens theargument for building or expanding roads.(60) On the other hand, many of the regionaldevelopment plans designed to promote compactcentral city development and transit may bepredicated on an analysis that assumes largefuture traffic increases in a “business as usual”(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects ofregional planning are dependent on trafficforecasts. Thats not to say that such plans arenecessarily wrong, but clearly revised trafficreality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just(70) highway building ones.Urbanists and policy makers of all stripesneed to think about the full implications of peakcar. At a minimum, the traditional “you cantbuild your way out of congestion” rhetoric should(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a morenuanced approach that neither overestimatesdemand, nor ignores the problems caused byrapid growth in some regions and pockets ofcongestion in others.Q.The graph best supports which claim about the relationship between economic recessions in the U.S. and total vehicle miles driven on U.S. roads?a)In the last four decades, recessions that last longer than a year correspond to a decrease in total vehicle miles.b)The six most recent recession periods each corresponded to an increase in total vehicle miles.c)Recent recessions in the U.S. do not correlate strongly with either an increase or decrease in total vehicle miles.d)In the last four decades, the longer a recession lasts, the more dramatically total vehicle miles decline.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? defined & explained in the simplest way possible. Besides giving the explanation of

Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.As traffic levels in the United States decline indefiance of forecasts projecting major increases, anumber of commentators have claimed that wevereached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comesto an end. But while this has been celebrated bymany urbanists as undermining plans for moreroads, we have yet to face the implications peakcar has for public policy.(10) For a long time, urbanists have embracedSays Law of Markets for roads: increasing thesupply of driving lanes only increases the numberof drivers to fill them, hence building more roadsto reduce congestion is pointless. But if weve(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really canbuild our way out of congestion after all.Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallenin recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked ona per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travelshows a marked reversal.These data are complemented by a slew ofrecent stories about the poor financial(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in partfrom traffic falling far below projections. On theIndiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% ineight years, in contrast with a forecasted increaseof 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.(30) Many of the trends that drove high trafficgrowth in the past have largely been playedout: household size declines, suburbanization,the entry of women into the workforce, onecar per driver, etc. Thats not to say these will(35) necessarily reverse. But weve reached the pointof diminishing returns, particularly in terms ofhow many more women will join the labor force.This is potentially very good fiscal news,especially given tight budgets. Clearly many(40) freeway expansion projects that have been drivenby speculative demand should be revisited. Fromtop to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate theirforecasting models to better correspond to reality,and then revisit highway plans accordingly.(45)But we must also pay attention to the flipside of peak car. Although speculative highwayexpansion projects may be dubious, there may begood reasons now to build projects designed toalleviate already exiting congestion. Places like(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, whichhas great economic and social consequences,not the least of which is the value of untold hourslost sitting in traffic. Although some projectsthere might indeed be boondoggles, maybe its(55) worth building some of the planned freewayexpansions there in light of peak car. In short,in some cases—particularly where Says Law nolonger seems to apply—peak car strengthens theargument for building or expanding roads.(60) On the other hand, many of the regionaldevelopment plans designed to promote compactcentral city development and transit may bepredicated on an analysis that assumes largefuture traffic increases in a “business as usual”(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects ofregional planning are dependent on trafficforecasts. Thats not to say that such plans arenecessarily wrong, but clearly revised trafficreality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just(70) highway building ones.Urbanists and policy makers of all stripesneed to think about the full implications of peakcar. At a minimum, the traditional “you cantbuild your way out of congestion” rhetoric should(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a morenuanced approach that neither overestimatesdemand, nor ignores the problems caused byrapid growth in some regions and pockets ofcongestion in others.Q.The graph best supports which claim about the relationship between economic recessions in the U.S. and total vehicle miles driven on U.S. roads?a)In the last four decades, recessions that last longer than a year correspond to a decrease in total vehicle miles.b)The six most recent recession periods each corresponded to an increase in total vehicle miles.c)Recent recessions in the U.S. do not correlate strongly with either an increase or decrease in total vehicle miles.d)In the last four decades, the longer a recession lasts, the more dramatically total vehicle miles decline.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer?, a detailed solution for Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.As traffic levels in the United States decline indefiance of forecasts projecting major increases, anumber of commentators have claimed that wevereached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comesto an end. But while this has been celebrated bymany urbanists as undermining plans for moreroads, we have yet to face the implications peakcar has for public policy.(10) For a long time, urbanists have embracedSays Law of Markets for roads: increasing thesupply of driving lanes only increases the numberof drivers to fill them, hence building more roadsto reduce congestion is pointless. But if weve(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really canbuild our way out of congestion after all.Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallenin recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked ona per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travelshows a marked reversal.These data are complemented by a slew ofrecent stories about the poor financial(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in partfrom traffic falling far below projections. On theIndiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% ineight years, in contrast with a forecasted increaseof 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.(30) Many of the trends that drove high trafficgrowth in the past have largely been playedout: household size declines, suburbanization,the entry of women into the workforce, onecar per driver, etc. Thats not to say these will(35) necessarily reverse. But weve reached the pointof diminishing returns, particularly in terms ofhow many more women will join the labor force.This is potentially very good fiscal news,especially given tight budgets. Clearly many(40) freeway expansion projects that have been drivenby speculative demand should be revisited. Fromtop to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate theirforecasting models to better correspond to reality,and then revisit highway plans accordingly.(45)But we must also pay attention to the flipside of peak car. Although speculative highwayexpansion projects may be dubious, there may begood reasons now to build projects designed toalleviate already exiting congestion. Places like(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, whichhas great economic and social consequences,not the least of which is the value of untold hourslost sitting in traffic. Although some projectsthere might indeed be boondoggles, maybe its(55) worth building some of the planned freewayexpansions there in light of peak car. In short,in some cases—particularly where Says Law nolonger seems to apply—peak car strengthens theargument for building or expanding roads.(60) On the other hand, many of the regionaldevelopment plans designed to promote compactcentral city development and transit may bepredicated on an analysis that assumes largefuture traffic increases in a “business as usual”(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects ofregional planning are dependent on trafficforecasts. Thats not to say that such plans arenecessarily wrong, but clearly revised trafficreality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just(70) highway building ones.Urbanists and policy makers of all stripesneed to think about the full implications of peakcar. At a minimum, the traditional “you cantbuild your way out of congestion” rhetoric should(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a morenuanced approach that neither overestimatesdemand, nor ignores the problems caused byrapid growth in some regions and pockets ofcongestion in others.Q.The graph best supports which claim about the relationship between economic recessions in the U.S. and total vehicle miles driven on U.S. roads?a)In the last four decades, recessions that last longer than a year correspond to a decrease in total vehicle miles.b)The six most recent recession periods each corresponded to an increase in total vehicle miles.c)Recent recessions in the U.S. do not correlate strongly with either an increase or decrease in total vehicle miles.d)In the last four decades, the longer a recession lasts, the more dramatically total vehicle miles decline.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? has been provided alongside types of Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.As traffic levels in the United States decline indefiance of forecasts projecting major increases, anumber of commentators have claimed that wevereached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comesto an end. But while this has been celebrated bymany urbanists as undermining plans for moreroads, we have yet to face the implications peakcar has for public policy.(10) For a long time, urbanists have embracedSays Law of Markets for roads: increasing thesupply of driving lanes only increases the numberof drivers to fill them, hence building more roadsto reduce congestion is pointless. But if weve(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really canbuild our way out of congestion after all.Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallenin recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked ona per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travelshows a marked reversal.These data are complemented by a slew ofrecent stories about the poor financial(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in partfrom traffic falling far below projections. On theIndiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% ineight years, in contrast with a forecasted increaseof 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.(30) Many of the trends that drove high trafficgrowth in the past have largely been playedout: household size declines, suburbanization,the entry of women into the workforce, onecar per driver, etc. Thats not to say these will(35) necessarily reverse. But weve reached the pointof diminishing returns, particularly in terms ofhow many more women will join the labor force.This is potentially very good fiscal news,especially given tight budgets. Clearly many(40) freeway expansion projects that have been drivenby speculative demand should be revisited. Fromtop to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate theirforecasting models to better correspond to reality,and then revisit highway plans accordingly.(45)But we must also pay attention to the flipside of peak car. Although speculative highwayexpansion projects may be dubious, there may begood reasons now to build projects designed toalleviate already exiting congestion. Places like(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, whichhas great economic and social consequences,not the least of which is the value of untold hourslost sitting in traffic. Although some projectsthere might indeed be boondoggles, maybe its(55) worth building some of the planned freewayexpansions there in light of peak car. In short,in some cases—particularly where Says Law nolonger seems to apply—peak car strengthens theargument for building or expanding roads.(60) On the other hand, many of the regionaldevelopment plans designed to promote compactcentral city development and transit may bepredicated on an analysis that assumes largefuture traffic increases in a “business as usual”(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects ofregional planning are dependent on trafficforecasts. Thats not to say that such plans arenecessarily wrong, but clearly revised trafficreality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just(70) highway building ones.Urbanists and policy makers of all stripesneed to think about the full implications of peakcar. At a minimum, the traditional “you cantbuild your way out of congestion” rhetoric should(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a morenuanced approach that neither overestimatesdemand, nor ignores the problems caused byrapid growth in some regions and pockets ofcongestion in others.Q.The graph best supports which claim about the relationship between economic recessions in the U.S. and total vehicle miles driven on U.S. roads?a)In the last four decades, recessions that last longer than a year correspond to a decrease in total vehicle miles.b)The six most recent recession periods each corresponded to an increase in total vehicle miles.c)Recent recessions in the U.S. do not correlate strongly with either an increase or decrease in total vehicle miles.d)In the last four decades, the longer a recession lasts, the more dramatically total vehicle miles decline.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? theory, EduRev gives you an

ample number of questions to practice Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.The following is adapted from Aaron M. Renn, “Urbanists Need to Face the Full Implications of Peak Car," published in New Geography (newgeography. com) on November 25, 2014.As traffic levels in the United States decline indefiance of forecasts projecting major increases, anumber of commentators have claimed that wevereached “peak car,” the point at which the rise in(5) vehicle miles traveled in America finally comesto an end. But while this has been celebrated bymany urbanists as undermining plans for moreroads, we have yet to face the implications peakcar has for public policy.(10) For a long time, urbanists have embracedSays Law of Markets for roads: increasing thesupply of driving lanes only increases the numberof drivers to fill them, hence building more roadsto reduce congestion is pointless. But if weve(15) really reached peak car, maybe we really canbuild our way out of congestion after all.Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallenin recent years. Aggregate auto travel peaked ona per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since.(20) Per capita traffic levels in 2014 were back to 1994levels. Even looking at total (not per capita) travelshows a marked reversal.These data are complemented by a slew ofrecent stories about the poor financial(25) performance of toll roads, resulting in partfrom traffic falling far below projections. On theIndiana Toll Road, for example, traffic fell 11% ineight years, in contrast with a forecasted increaseof 22%, and so the concessionaire went bankrupt.(30) Many of the trends that drove high trafficgrowth in the past have largely been playedout: household size declines, suburbanization,the entry of women into the workforce, onecar per driver, etc. Thats not to say these will(35) necessarily reverse. But weve reached the pointof diminishing returns, particularly in terms ofhow many more women will join the labor force.This is potentially very good fiscal news,especially given tight budgets. Clearly many(40) freeway expansion projects that have been drivenby speculative demand should be revisited. Fromtop to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate theirforecasting models to better correspond to reality,and then revisit highway plans accordingly.(45)But we must also pay attention to the flipside of peak car. Although speculative highwayexpansion projects may be dubious, there may begood reasons now to build projects designed toalleviate already exiting congestion. Places like(50) Los Angeles remain chronically congested, whichhas great economic and social consequences,not the least of which is the value of untold hourslost sitting in traffic. Although some projectsthere might indeed be boondoggles, maybe its(55) worth building some of the planned freewayexpansions there in light of peak car. In short,in some cases—particularly where Says Law nolonger seems to apply—peak car strengthens theargument for building or expanding roads.(60) On the other hand, many of the regionaldevelopment plans designed to promote compactcentral city development and transit may bepredicated on an analysis that assumes largefuture traffic increases in a “business as usual”(65) scenario. Not just highways but all aspects ofregional planning are dependent on trafficforecasts. Thats not to say that such plans arenecessarily wrong, but clearly revised trafficreality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just(70) highway building ones.Urbanists and policy makers of all stripesneed to think about the full implications of peakcar. At a minimum, the traditional “you cantbuild your way out of congestion” rhetoric should(75) be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a morenuanced approach that neither overestimatesdemand, nor ignores the problems caused byrapid growth in some regions and pockets ofcongestion in others.Q.The graph best supports which claim about the relationship between economic recessions in the U.S. and total vehicle miles driven on U.S. roads?a)In the last four decades, recessions that last longer than a year correspond to a decrease in total vehicle miles.b)The six most recent recession periods each corresponded to an increase in total vehicle miles.c)Recent recessions in the U.S. do not correlate strongly with either an increase or decrease in total vehicle miles.d)In the last four decades, the longer a recession lasts, the more dramatically total vehicle miles decline.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? tests, examples and also practice SAT tests.

|

Explore Courses for SAT exam

|

|

Signup for Free!

Signup to see your scores go up within 7 days! Learn & Practice with 1000+ FREE Notes, Videos & Tests.