SAT Exam > SAT Questions > Question based on the following passages and ...

Start Learning for Free

Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is adapted from Radhika Singh, “Mice Utopias and the Behavioral Sink," published July 31, 2015 in the blog of The Borgen Project (borgenproject. org). Passage 2 is adapted from Frans de Waal, “Is it 'Behavioral Sink' or Resource Distribution?" published in Scientific American online July 21, 2010.

Passage 1

In 1972, behavioral researcher John Calhoun

introduced four breeding pairs of mice into a box

9-feet square and 4.5-feet high. It was a “perfect

(5) universe:” the mice were safe from predators and

disease and given ample food and water. They

doubled in population every 55 days.

However, within a year males stopped

defending their territory, random violence broke

(10) out, and female mice attacked their own offspring.

Normal social bonds and interactions completely

broke down. Infant abandonment soared, and

mortality climbed. Cannibalism appeared, even

though there was more than enough food. Fertile

(15) females closed themselves off from society, and

males of reproductive age—Calhoun called them

the “beautiful ones”—did nothing but eat, sleep

and groom.

Calhoun called this breakdown the

(20) “behavioral sink,” vand believed it came about

when there were too many mice and a lack of

important social roles for each one to play. Even

when enough of the population died off so that

only an optimal population remained, the mice

(25) were not able to return to their natural behavior.

This connection between a breakdown of

social bonds and violence was observed by Emile

Durkheim in the late 19th century. In traditional

societies, where family expectations and religion

(30) held sway, people enjoyed strong social bonds

and had distinct social roles to fill. However,

as they moved to cities, they found they were

fighting for a place in society. In exasperation and

a state of helplessness, many fell into poverty or

(35) turned to crime, violence and even suicide.

The fear of failing to be a productive member

of society and fulfilling social roles can also push

people, like the “beautiful ones,” into isolating

themselves. For instance, Japanese “hikikomori”

(40) refuse to leave their rooms, sometimes for years,

because they feel shame for being unable to fulfill

familial expectations.

However, it is not clear that a high population

density necessarily leads to a breakdown of

(45) society and social roles. Humans might be

able, with our ingenuity, to create social roles

for everyone and avoid the behavioral sink.

Some critics, such as psychologist Jonathan

Freedam, suggested that it was not the density of

(50) population that overwhelmed the mice but the

large number of social interactions they had to

deal with. Humans are able to avoid this, even

while living in a highly dense area.

Passage 2

In the 1960s, John Calhoun placed a group

(55) of rats in a room and observed how the animals

killed, sexually assaulted and, eventually,

cannibalized one another. This

behavioral deviancy led Calhoun to coin the phrase

“behavioral sink.”

(60) In no time, popularizers were comparing

politically motivated street riots with rat packs

and inner cities to behavioral sinks. Warning

that society was heading for either anarchy or

dictatorship, Robert Ardrey, a popular science

(65) journalist, remarked in 1970 on the voluntary

nature of human crowding and its ill effects. The

negative impact of crowding became a central

tenet of the voluminous literature on aggression.

In extrapolating from rodents to people,

(70) however, these writers were making a giant leap.

Compare, for instance, the per capita murder

rates with the number of people per square

kilometer in different nations. There is in fact no

statistically meaningful relation. Among free-

(75) market nations, the U.S. has the highest homicide

rate despite a low population density.

To see how other primates respond to being

packed together, we compared rhesus monkeys

in crowded cages with those roaming free

(80) on Morgan Island in South Carolina. We also

compared chimpanzees in indoor enclosures

with those living on large forested islands.

Nothing like the expected crowding effects

could be found. If anything, primates become

(85) more sociable in captivity, grooming each other

more—probably in an effort to counter the

potential of conflict, which is greater the closer

they live together. Primates are excellent at

conflict resolution.

(90) For the future of the world this means that

crowding by itself is perhaps not the problem it

is made it out to be. Resource distribution seems

the real issue. This was already true for Calhoun's

rats, the violence among them could be explained

(95) by concentrated food sources and competition.

Also for humans, I would worry more about

sustainability and resource distribution than

population density.

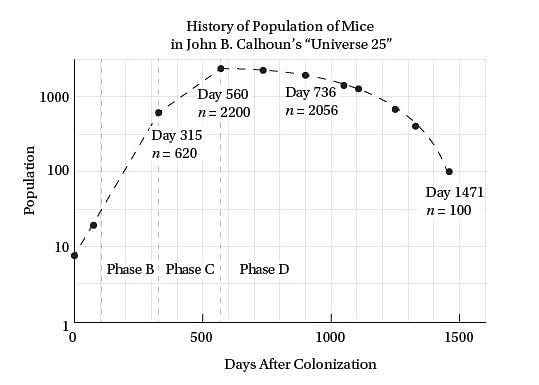

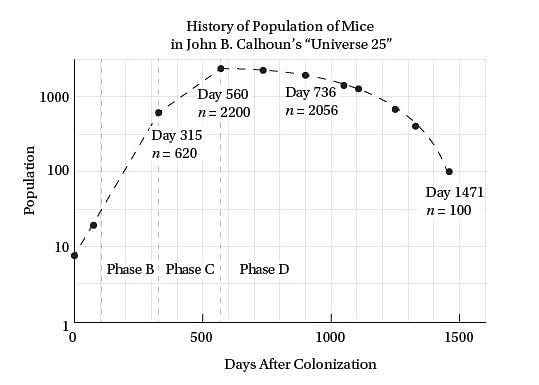

Phase A: Days 1–104 (Social Adjustment): Mice are introduced (4 males and 4 females). Nests are established.

Phase B: Days 105–315 (Rapid growth): Population doubles every 55 days.

Male strength corresponds to frequency of reproduction. As crowding develops, immature males begin to proliferate within the population.

Phase C: Days 316–560 (Stagnation): Population doubles every 145 days.

Male ability to defend territory declines. Nursing females become more aggressive, even towards own offspring. By midway point in Phase C, virtually all young are prematurely rejected by their mothers. Although 20% of nest sites are unoccupied, there is severe overcrowding in other sites.

Withdrawn males become more violent toward each other.

Phase D: Days 561–1588 (Death): Population begins to decline on Day 561.

Incidences of pregnancy decline rapidly with no young surviving. The last 1000 mice born grow up with no social skills or ability to defend territory. The males become withdrawn and obsessed with their own grooming.

Passage 1 is adapted from Radhika Singh, “Mice Utopias and the Behavioral Sink," published July 31, 2015 in the blog of The Borgen Project (borgenproject. org). Passage 2 is adapted from Frans de Waal, “Is it 'Behavioral Sink' or Resource Distribution?" published in Scientific American online July 21, 2010.

Passage 1

In 1972, behavioral researcher John Calhoun

introduced four breeding pairs of mice into a box

9-feet square and 4.5-feet high. It was a “perfect

(5) universe:” the mice were safe from predators and

disease and given ample food and water. They

doubled in population every 55 days.

However, within a year males stopped

defending their territory, random violence broke

(10) out, and female mice attacked their own offspring.

Normal social bonds and interactions completely

broke down. Infant abandonment soared, and

mortality climbed. Cannibalism appeared, even

though there was more than enough food. Fertile

(15) females closed themselves off from society, and

males of reproductive age—Calhoun called them

the “beautiful ones”—did nothing but eat, sleep

and groom.

Calhoun called this breakdown the

(20) “behavioral sink,” vand believed it came about

when there were too many mice and a lack of

important social roles for each one to play. Even

when enough of the population died off so that

only an optimal population remained, the mice

(25) were not able to return to their natural behavior.

This connection between a breakdown of

social bonds and violence was observed by Emile

Durkheim in the late 19th century. In traditional

societies, where family expectations and religion

(30) held sway, people enjoyed strong social bonds

and had distinct social roles to fill. However,

as they moved to cities, they found they were

fighting for a place in society. In exasperation and

a state of helplessness, many fell into poverty or

(35) turned to crime, violence and even suicide.

The fear of failing to be a productive member

of society and fulfilling social roles can also push

people, like the “beautiful ones,” into isolating

themselves. For instance, Japanese “hikikomori”

(40) refuse to leave their rooms, sometimes for years,

because they feel shame for being unable to fulfill

familial expectations.

However, it is not clear that a high population

density necessarily leads to a breakdown of

(45) society and social roles. Humans might be

able, with our ingenuity, to create social roles

for everyone and avoid the behavioral sink.

Some critics, such as psychologist Jonathan

Freedam, suggested that it was not the density of

(50) population that overwhelmed the mice but the

large number of social interactions they had to

deal with. Humans are able to avoid this, even

while living in a highly dense area.

Passage 2

In the 1960s, John Calhoun placed a group

(55) of rats in a room and observed how the animals

killed, sexually assaulted and, eventually,

cannibalized one another. This

behavioral deviancy led Calhoun to coin the phrase

“behavioral sink.”

(60) In no time, popularizers were comparing

politically motivated street riots with rat packs

and inner cities to behavioral sinks. Warning

that society was heading for either anarchy or

dictatorship, Robert Ardrey, a popular science

(65) journalist, remarked in 1970 on the voluntary

nature of human crowding and its ill effects. The

negative impact of crowding became a central

tenet of the voluminous literature on aggression.

In extrapolating from rodents to people,

(70) however, these writers were making a giant leap.

Compare, for instance, the per capita murder

rates with the number of people per square

kilometer in different nations. There is in fact no

statistically meaningful relation. Among free-

(75) market nations, the U.S. has the highest homicide

rate despite a low population density.

To see how other primates respond to being

packed together, we compared rhesus monkeys

in crowded cages with those roaming free

(80) on Morgan Island in South Carolina. We also

compared chimpanzees in indoor enclosures

with those living on large forested islands.

Nothing like the expected crowding effects

could be found. If anything, primates become

(85) more sociable in captivity, grooming each other

more—probably in an effort to counter the

potential of conflict, which is greater the closer

they live together. Primates are excellent at

conflict resolution.

(90) For the future of the world this means that

crowding by itself is perhaps not the problem it

is made it out to be. Resource distribution seems

the real issue. This was already true for Calhoun's

rats, the violence among them could be explained

(95) by concentrated food sources and competition.

Also for humans, I would worry more about

sustainability and resource distribution than

population density.

Phase A: Days 1–104 (Social Adjustment): Mice are introduced (4 males and 4 females). Nests are established.

Phase B: Days 105–315 (Rapid growth): Population doubles every 55 days.

Male strength corresponds to frequency of reproduction. As crowding develops, immature males begin to proliferate within the population.

Phase C: Days 316–560 (Stagnation): Population doubles every 145 days.

Male ability to defend territory declines. Nursing females become more aggressive, even towards own offspring. By midway point in Phase C, virtually all young are prematurely rejected by their mothers. Although 20% of nest sites are unoccupied, there is severe overcrowding in other sites.

Withdrawn males become more violent toward each other.

Phase D: Days 561–1588 (Death): Population begins to decline on Day 561.

Incidences of pregnancy decline rapidly with no young surviving. The last 1000 mice born grow up with no social skills or ability to defend territory. The males become withdrawn and obsessed with their own grooming.

Q. As used in line 2, “introduced” most nearly means

- a)pioneered.

- b)acquainted.

- c)inserted.

- d)announced.

Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer?

Verified Answer

Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.Pa...

The statement that Calhoun introduced four breeding pairs of mice into a box (lines 1–2), the author means that Calhoun inserted the rats into their new environment.

|

Explore Courses for SAT exam

|

|

Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.Passage 1 is adapted from Radhika Singh, “Mice Utopias and the Behavioral Sink," published July 31, 2015 in the blog of The Borgen Project (borgenproject. org). Passage 2 is adapted from Frans de Waal, “Is it Behavioral Sink or Resource Distribution?" published in Scientific American online July 21, 2010.Passage 1In 1972, behavioral researcher John Calhounintroduced four breeding pairs of mice into a box9-feet square and 4.5-feet high. It was a “perfect(5) universe:” the mice were safe from predators anddisease and given ample food and water. Theydoubled in population every 55 days.However, within a year males stoppeddefending their territory, random violence broke(10) out, and female mice attacked their own offspring.Normal social bonds and interactions completelybroke down. Infant abandonment soared, andmortality climbed. Cannibalism appeared, eventhough there was more than enough food. Fertile(15) females closed themselves off from society, andmales of reproductive age—Calhoun called themthe “beautiful ones”—did nothing but eat, sleepand groom.Calhoun called this breakdown the(20) “behavioral sink,” vand believed it came aboutwhen there were too many mice and a lack ofimportant social roles for each one to play. Evenwhen enough of the population died off so thatonly an optimal population remained, the mice(25) were not able to return to their natural behavior.This connection between a breakdown ofsocial bonds and violence was observed by EmileDurkheim in the late 19th century. In traditionalsocieties, where family expectations and religion(30) held sway, people enjoyed strong social bondsand had distinct social roles to fill. However,as they moved to cities, they found they werefighting for a place in society. In exasperation anda state of helplessness, many fell into poverty or(35) turned to crime, violence and even suicide.The fear of failing to be a productive memberof society and fulfilling social roles can also pushpeople, like the “beautiful ones,” into isolatingthemselves. For instance, Japanese “hikikomori”(40) refuse to leave their rooms, sometimes for years,because they feel shame for being unable to fulfillfamilial expectations.However, it is not clear that a high populationdensity necessarily leads to a breakdown of(45) society and social roles. Humans might beable, with our ingenuity, to create social rolesfor everyone and avoid the behavioral sink.Some critics, such as psychologist JonathanFreedam, suggested that it was not the density of(50) population that overwhelmed the mice but thelarge number of social interactions they had todeal with. Humans are able to avoid this, evenwhile living in a highly dense area.Passage 2In the 1960s, John Calhoun placed a group(55) of rats in a room and observed how the animalskilled, sexually assaulted and, eventually,cannibalized one another. Thisbehavioral deviancy led Calhoun to coin the phrase“behavioral sink.”(60) In no time, popularizers were comparingpolitically motivated street riots with rat packsand inner cities to behavioral sinks. Warningthat society was heading for either anarchy ordictatorship, Robert Ardrey, a popular science(65) journalist, remarked in 1970 on the voluntarynature of human crowding and its ill effects. Thenegative impact of crowding became a centraltenet of the voluminous literature on aggression.In extrapolating from rodents to people,(70) however, these writers were making a giant leap.Compare, for instance, the per capita murderrates with the number of people per squarekilometer in different nations. There is in fact nostatistically meaningful relation. Among free-(75) market nations, the U.S. has the highest homiciderate despite a low population density.To see how other primates respond to beingpacked together, we compared rhesus monkeysin crowded cages with those roaming free(80) on Morgan Island in South Carolina. We alsocompared chimpanzees in indoor enclosureswith those living on large forested islands.Nothing like the expected crowding effectscould be found. If anything, primates become(85) more sociable in captivity, grooming each othermore—probably in an effort to counter thepotential of conflict, which is greater the closerthey live together. Primates are excellent atconflict resolution.(90) For the future of the world this means thatcrowding by itself is perhaps not the problem itis made it out to be. Resource distribution seemsthe real issue. This was already true for Calhounsrats, the violence among them could be explained(95) by concentrated food sources and competition.Also for humans, I would worry more aboutsustainability and resource distribution thanpopulation density.Phase A: Days 1–104 (Social Adjustment): Mice are introduced (4 males and 4 females). Nests are established.Phase B: Days 105–315 (Rapid growth): Population doubles every 55 days.Male strength corresponds to frequency of reproduction. As crowding develops, immature males begin to proliferate within the population.Phase C: Days 316–560 (Stagnation): Population doubles every 145 days.Male ability to defend territory declines. Nursing females become more aggressive, even towards own offspring. By midway point in Phase C, virtually all young are prematurely rejected by their mothers. Although 20% of nest sites are unoccupied, there is severe overcrowding in other sites.Withdrawn males become more violent toward each other.Phase D: Days 561–1588 (Death): Population begins to decline on Day 561.Incidences of pregnancy decline rapidly with no young surviving. The last 1000 mice born grow up with no social skills or ability to defend territory. The males become withdrawn and obsessed with their own grooming.Q.As used in line 2, “introduced” most nearly meansa)pioneered.b)acquainted.c)inserted.d)announced.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer?

Question Description

Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.Passage 1 is adapted from Radhika Singh, “Mice Utopias and the Behavioral Sink," published July 31, 2015 in the blog of The Borgen Project (borgenproject. org). Passage 2 is adapted from Frans de Waal, “Is it Behavioral Sink or Resource Distribution?" published in Scientific American online July 21, 2010.Passage 1In 1972, behavioral researcher John Calhounintroduced four breeding pairs of mice into a box9-feet square and 4.5-feet high. It was a “perfect(5) universe:” the mice were safe from predators anddisease and given ample food and water. Theydoubled in population every 55 days.However, within a year males stoppeddefending their territory, random violence broke(10) out, and female mice attacked their own offspring.Normal social bonds and interactions completelybroke down. Infant abandonment soared, andmortality climbed. Cannibalism appeared, eventhough there was more than enough food. Fertile(15) females closed themselves off from society, andmales of reproductive age—Calhoun called themthe “beautiful ones”—did nothing but eat, sleepand groom.Calhoun called this breakdown the(20) “behavioral sink,” vand believed it came aboutwhen there were too many mice and a lack ofimportant social roles for each one to play. Evenwhen enough of the population died off so thatonly an optimal population remained, the mice(25) were not able to return to their natural behavior.This connection between a breakdown ofsocial bonds and violence was observed by EmileDurkheim in the late 19th century. In traditionalsocieties, where family expectations and religion(30) held sway, people enjoyed strong social bondsand had distinct social roles to fill. However,as they moved to cities, they found they werefighting for a place in society. In exasperation anda state of helplessness, many fell into poverty or(35) turned to crime, violence and even suicide.The fear of failing to be a productive memberof society and fulfilling social roles can also pushpeople, like the “beautiful ones,” into isolatingthemselves. For instance, Japanese “hikikomori”(40) refuse to leave their rooms, sometimes for years,because they feel shame for being unable to fulfillfamilial expectations.However, it is not clear that a high populationdensity necessarily leads to a breakdown of(45) society and social roles. Humans might beable, with our ingenuity, to create social rolesfor everyone and avoid the behavioral sink.Some critics, such as psychologist JonathanFreedam, suggested that it was not the density of(50) population that overwhelmed the mice but thelarge number of social interactions they had todeal with. Humans are able to avoid this, evenwhile living in a highly dense area.Passage 2In the 1960s, John Calhoun placed a group(55) of rats in a room and observed how the animalskilled, sexually assaulted and, eventually,cannibalized one another. Thisbehavioral deviancy led Calhoun to coin the phrase“behavioral sink.”(60) In no time, popularizers were comparingpolitically motivated street riots with rat packsand inner cities to behavioral sinks. Warningthat society was heading for either anarchy ordictatorship, Robert Ardrey, a popular science(65) journalist, remarked in 1970 on the voluntarynature of human crowding and its ill effects. Thenegative impact of crowding became a centraltenet of the voluminous literature on aggression.In extrapolating from rodents to people,(70) however, these writers were making a giant leap.Compare, for instance, the per capita murderrates with the number of people per squarekilometer in different nations. There is in fact nostatistically meaningful relation. Among free-(75) market nations, the U.S. has the highest homiciderate despite a low population density.To see how other primates respond to beingpacked together, we compared rhesus monkeysin crowded cages with those roaming free(80) on Morgan Island in South Carolina. We alsocompared chimpanzees in indoor enclosureswith those living on large forested islands.Nothing like the expected crowding effectscould be found. If anything, primates become(85) more sociable in captivity, grooming each othermore—probably in an effort to counter thepotential of conflict, which is greater the closerthey live together. Primates are excellent atconflict resolution.(90) For the future of the world this means thatcrowding by itself is perhaps not the problem itis made it out to be. Resource distribution seemsthe real issue. This was already true for Calhounsrats, the violence among them could be explained(95) by concentrated food sources and competition.Also for humans, I would worry more aboutsustainability and resource distribution thanpopulation density.Phase A: Days 1–104 (Social Adjustment): Mice are introduced (4 males and 4 females). Nests are established.Phase B: Days 105–315 (Rapid growth): Population doubles every 55 days.Male strength corresponds to frequency of reproduction. As crowding develops, immature males begin to proliferate within the population.Phase C: Days 316–560 (Stagnation): Population doubles every 145 days.Male ability to defend territory declines. Nursing females become more aggressive, even towards own offspring. By midway point in Phase C, virtually all young are prematurely rejected by their mothers. Although 20% of nest sites are unoccupied, there is severe overcrowding in other sites.Withdrawn males become more violent toward each other.Phase D: Days 561–1588 (Death): Population begins to decline on Day 561.Incidences of pregnancy decline rapidly with no young surviving. The last 1000 mice born grow up with no social skills or ability to defend territory. The males become withdrawn and obsessed with their own grooming.Q.As used in line 2, “introduced” most nearly meansa)pioneered.b)acquainted.c)inserted.d)announced.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? for SAT 2025 is part of SAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the SAT exam syllabus. Information about Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.Passage 1 is adapted from Radhika Singh, “Mice Utopias and the Behavioral Sink," published July 31, 2015 in the blog of The Borgen Project (borgenproject. org). Passage 2 is adapted from Frans de Waal, “Is it Behavioral Sink or Resource Distribution?" published in Scientific American online July 21, 2010.Passage 1In 1972, behavioral researcher John Calhounintroduced four breeding pairs of mice into a box9-feet square and 4.5-feet high. It was a “perfect(5) universe:” the mice were safe from predators anddisease and given ample food and water. Theydoubled in population every 55 days.However, within a year males stoppeddefending their territory, random violence broke(10) out, and female mice attacked their own offspring.Normal social bonds and interactions completelybroke down. Infant abandonment soared, andmortality climbed. Cannibalism appeared, eventhough there was more than enough food. Fertile(15) females closed themselves off from society, andmales of reproductive age—Calhoun called themthe “beautiful ones”—did nothing but eat, sleepand groom.Calhoun called this breakdown the(20) “behavioral sink,” vand believed it came aboutwhen there were too many mice and a lack ofimportant social roles for each one to play. Evenwhen enough of the population died off so thatonly an optimal population remained, the mice(25) were not able to return to their natural behavior.This connection between a breakdown ofsocial bonds and violence was observed by EmileDurkheim in the late 19th century. In traditionalsocieties, where family expectations and religion(30) held sway, people enjoyed strong social bondsand had distinct social roles to fill. However,as they moved to cities, they found they werefighting for a place in society. In exasperation anda state of helplessness, many fell into poverty or(35) turned to crime, violence and even suicide.The fear of failing to be a productive memberof society and fulfilling social roles can also pushpeople, like the “beautiful ones,” into isolatingthemselves. For instance, Japanese “hikikomori”(40) refuse to leave their rooms, sometimes for years,because they feel shame for being unable to fulfillfamilial expectations.However, it is not clear that a high populationdensity necessarily leads to a breakdown of(45) society and social roles. Humans might beable, with our ingenuity, to create social rolesfor everyone and avoid the behavioral sink.Some critics, such as psychologist JonathanFreedam, suggested that it was not the density of(50) population that overwhelmed the mice but thelarge number of social interactions they had todeal with. Humans are able to avoid this, evenwhile living in a highly dense area.Passage 2In the 1960s, John Calhoun placed a group(55) of rats in a room and observed how the animalskilled, sexually assaulted and, eventually,cannibalized one another. Thisbehavioral deviancy led Calhoun to coin the phrase“behavioral sink.”(60) In no time, popularizers were comparingpolitically motivated street riots with rat packsand inner cities to behavioral sinks. Warningthat society was heading for either anarchy ordictatorship, Robert Ardrey, a popular science(65) journalist, remarked in 1970 on the voluntarynature of human crowding and its ill effects. Thenegative impact of crowding became a centraltenet of the voluminous literature on aggression.In extrapolating from rodents to people,(70) however, these writers were making a giant leap.Compare, for instance, the per capita murderrates with the number of people per squarekilometer in different nations. There is in fact nostatistically meaningful relation. Among free-(75) market nations, the U.S. has the highest homiciderate despite a low population density.To see how other primates respond to beingpacked together, we compared rhesus monkeysin crowded cages with those roaming free(80) on Morgan Island in South Carolina. We alsocompared chimpanzees in indoor enclosureswith those living on large forested islands.Nothing like the expected crowding effectscould be found. If anything, primates become(85) more sociable in captivity, grooming each othermore—probably in an effort to counter thepotential of conflict, which is greater the closerthey live together. Primates are excellent atconflict resolution.(90) For the future of the world this means thatcrowding by itself is perhaps not the problem itis made it out to be. Resource distribution seemsthe real issue. This was already true for Calhounsrats, the violence among them could be explained(95) by concentrated food sources and competition.Also for humans, I would worry more aboutsustainability and resource distribution thanpopulation density.Phase A: Days 1–104 (Social Adjustment): Mice are introduced (4 males and 4 females). Nests are established.Phase B: Days 105–315 (Rapid growth): Population doubles every 55 days.Male strength corresponds to frequency of reproduction. As crowding develops, immature males begin to proliferate within the population.Phase C: Days 316–560 (Stagnation): Population doubles every 145 days.Male ability to defend territory declines. Nursing females become more aggressive, even towards own offspring. By midway point in Phase C, virtually all young are prematurely rejected by their mothers. Although 20% of nest sites are unoccupied, there is severe overcrowding in other sites.Withdrawn males become more violent toward each other.Phase D: Days 561–1588 (Death): Population begins to decline on Day 561.Incidences of pregnancy decline rapidly with no young surviving. The last 1000 mice born grow up with no social skills or ability to defend territory. The males become withdrawn and obsessed with their own grooming.Q.As used in line 2, “introduced” most nearly meansa)pioneered.b)acquainted.c)inserted.d)announced.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for SAT 2025 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.Passage 1 is adapted from Radhika Singh, “Mice Utopias and the Behavioral Sink," published July 31, 2015 in the blog of The Borgen Project (borgenproject. org). Passage 2 is adapted from Frans de Waal, “Is it Behavioral Sink or Resource Distribution?" published in Scientific American online July 21, 2010.Passage 1In 1972, behavioral researcher John Calhounintroduced four breeding pairs of mice into a box9-feet square and 4.5-feet high. It was a “perfect(5) universe:” the mice were safe from predators anddisease and given ample food and water. Theydoubled in population every 55 days.However, within a year males stoppeddefending their territory, random violence broke(10) out, and female mice attacked their own offspring.Normal social bonds and interactions completelybroke down. Infant abandonment soared, andmortality climbed. Cannibalism appeared, eventhough there was more than enough food. Fertile(15) females closed themselves off from society, andmales of reproductive age—Calhoun called themthe “beautiful ones”—did nothing but eat, sleepand groom.Calhoun called this breakdown the(20) “behavioral sink,” vand believed it came aboutwhen there were too many mice and a lack ofimportant social roles for each one to play. Evenwhen enough of the population died off so thatonly an optimal population remained, the mice(25) were not able to return to their natural behavior.This connection between a breakdown ofsocial bonds and violence was observed by EmileDurkheim in the late 19th century. In traditionalsocieties, where family expectations and religion(30) held sway, people enjoyed strong social bondsand had distinct social roles to fill. However,as they moved to cities, they found they werefighting for a place in society. In exasperation anda state of helplessness, many fell into poverty or(35) turned to crime, violence and even suicide.The fear of failing to be a productive memberof society and fulfilling social roles can also pushpeople, like the “beautiful ones,” into isolatingthemselves. For instance, Japanese “hikikomori”(40) refuse to leave their rooms, sometimes for years,because they feel shame for being unable to fulfillfamilial expectations.However, it is not clear that a high populationdensity necessarily leads to a breakdown of(45) society and social roles. Humans might beable, with our ingenuity, to create social rolesfor everyone and avoid the behavioral sink.Some critics, such as psychologist JonathanFreedam, suggested that it was not the density of(50) population that overwhelmed the mice but thelarge number of social interactions they had todeal with. Humans are able to avoid this, evenwhile living in a highly dense area.Passage 2In the 1960s, John Calhoun placed a group(55) of rats in a room and observed how the animalskilled, sexually assaulted and, eventually,cannibalized one another. Thisbehavioral deviancy led Calhoun to coin the phrase“behavioral sink.”(60) In no time, popularizers were comparingpolitically motivated street riots with rat packsand inner cities to behavioral sinks. Warningthat society was heading for either anarchy ordictatorship, Robert Ardrey, a popular science(65) journalist, remarked in 1970 on the voluntarynature of human crowding and its ill effects. Thenegative impact of crowding became a centraltenet of the voluminous literature on aggression.In extrapolating from rodents to people,(70) however, these writers were making a giant leap.Compare, for instance, the per capita murderrates with the number of people per squarekilometer in different nations. There is in fact nostatistically meaningful relation. Among free-(75) market nations, the U.S. has the highest homiciderate despite a low population density.To see how other primates respond to beingpacked together, we compared rhesus monkeysin crowded cages with those roaming free(80) on Morgan Island in South Carolina. We alsocompared chimpanzees in indoor enclosureswith those living on large forested islands.Nothing like the expected crowding effectscould be found. If anything, primates become(85) more sociable in captivity, grooming each othermore—probably in an effort to counter thepotential of conflict, which is greater the closerthey live together. Primates are excellent atconflict resolution.(90) For the future of the world this means thatcrowding by itself is perhaps not the problem itis made it out to be. Resource distribution seemsthe real issue. This was already true for Calhounsrats, the violence among them could be explained(95) by concentrated food sources and competition.Also for humans, I would worry more aboutsustainability and resource distribution thanpopulation density.Phase A: Days 1–104 (Social Adjustment): Mice are introduced (4 males and 4 females). Nests are established.Phase B: Days 105–315 (Rapid growth): Population doubles every 55 days.Male strength corresponds to frequency of reproduction. As crowding develops, immature males begin to proliferate within the population.Phase C: Days 316–560 (Stagnation): Population doubles every 145 days.Male ability to defend territory declines. Nursing females become more aggressive, even towards own offspring. By midway point in Phase C, virtually all young are prematurely rejected by their mothers. Although 20% of nest sites are unoccupied, there is severe overcrowding in other sites.Withdrawn males become more violent toward each other.Phase D: Days 561–1588 (Death): Population begins to decline on Day 561.Incidences of pregnancy decline rapidly with no young surviving. The last 1000 mice born grow up with no social skills or ability to defend territory. The males become withdrawn and obsessed with their own grooming.Q.As used in line 2, “introduced” most nearly meansa)pioneered.b)acquainted.c)inserted.d)announced.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer?.

Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.Passage 1 is adapted from Radhika Singh, “Mice Utopias and the Behavioral Sink," published July 31, 2015 in the blog of The Borgen Project (borgenproject. org). Passage 2 is adapted from Frans de Waal, “Is it Behavioral Sink or Resource Distribution?" published in Scientific American online July 21, 2010.Passage 1In 1972, behavioral researcher John Calhounintroduced four breeding pairs of mice into a box9-feet square and 4.5-feet high. It was a “perfect(5) universe:” the mice were safe from predators anddisease and given ample food and water. Theydoubled in population every 55 days.However, within a year males stoppeddefending their territory, random violence broke(10) out, and female mice attacked their own offspring.Normal social bonds and interactions completelybroke down. Infant abandonment soared, andmortality climbed. Cannibalism appeared, eventhough there was more than enough food. Fertile(15) females closed themselves off from society, andmales of reproductive age—Calhoun called themthe “beautiful ones”—did nothing but eat, sleepand groom.Calhoun called this breakdown the(20) “behavioral sink,” vand believed it came aboutwhen there were too many mice and a lack ofimportant social roles for each one to play. Evenwhen enough of the population died off so thatonly an optimal population remained, the mice(25) were not able to return to their natural behavior.This connection between a breakdown ofsocial bonds and violence was observed by EmileDurkheim in the late 19th century. In traditionalsocieties, where family expectations and religion(30) held sway, people enjoyed strong social bondsand had distinct social roles to fill. However,as they moved to cities, they found they werefighting for a place in society. In exasperation anda state of helplessness, many fell into poverty or(35) turned to crime, violence and even suicide.The fear of failing to be a productive memberof society and fulfilling social roles can also pushpeople, like the “beautiful ones,” into isolatingthemselves. For instance, Japanese “hikikomori”(40) refuse to leave their rooms, sometimes for years,because they feel shame for being unable to fulfillfamilial expectations.However, it is not clear that a high populationdensity necessarily leads to a breakdown of(45) society and social roles. Humans might beable, with our ingenuity, to create social rolesfor everyone and avoid the behavioral sink.Some critics, such as psychologist JonathanFreedam, suggested that it was not the density of(50) population that overwhelmed the mice but thelarge number of social interactions they had todeal with. Humans are able to avoid this, evenwhile living in a highly dense area.Passage 2In the 1960s, John Calhoun placed a group(55) of rats in a room and observed how the animalskilled, sexually assaulted and, eventually,cannibalized one another. Thisbehavioral deviancy led Calhoun to coin the phrase“behavioral sink.”(60) In no time, popularizers were comparingpolitically motivated street riots with rat packsand inner cities to behavioral sinks. Warningthat society was heading for either anarchy ordictatorship, Robert Ardrey, a popular science(65) journalist, remarked in 1970 on the voluntarynature of human crowding and its ill effects. Thenegative impact of crowding became a centraltenet of the voluminous literature on aggression.In extrapolating from rodents to people,(70) however, these writers were making a giant leap.Compare, for instance, the per capita murderrates with the number of people per squarekilometer in different nations. There is in fact nostatistically meaningful relation. Among free-(75) market nations, the U.S. has the highest homiciderate despite a low population density.To see how other primates respond to beingpacked together, we compared rhesus monkeysin crowded cages with those roaming free(80) on Morgan Island in South Carolina. We alsocompared chimpanzees in indoor enclosureswith those living on large forested islands.Nothing like the expected crowding effectscould be found. If anything, primates become(85) more sociable in captivity, grooming each othermore—probably in an effort to counter thepotential of conflict, which is greater the closerthey live together. Primates are excellent atconflict resolution.(90) For the future of the world this means thatcrowding by itself is perhaps not the problem itis made it out to be. Resource distribution seemsthe real issue. This was already true for Calhounsrats, the violence among them could be explained(95) by concentrated food sources and competition.Also for humans, I would worry more aboutsustainability and resource distribution thanpopulation density.Phase A: Days 1–104 (Social Adjustment): Mice are introduced (4 males and 4 females). Nests are established.Phase B: Days 105–315 (Rapid growth): Population doubles every 55 days.Male strength corresponds to frequency of reproduction. As crowding develops, immature males begin to proliferate within the population.Phase C: Days 316–560 (Stagnation): Population doubles every 145 days.Male ability to defend territory declines. Nursing females become more aggressive, even towards own offspring. By midway point in Phase C, virtually all young are prematurely rejected by their mothers. Although 20% of nest sites are unoccupied, there is severe overcrowding in other sites.Withdrawn males become more violent toward each other.Phase D: Days 561–1588 (Death): Population begins to decline on Day 561.Incidences of pregnancy decline rapidly with no young surviving. The last 1000 mice born grow up with no social skills or ability to defend territory. The males become withdrawn and obsessed with their own grooming.Q.As used in line 2, “introduced” most nearly meansa)pioneered.b)acquainted.c)inserted.d)announced.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? for SAT 2025 is part of SAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the SAT exam syllabus. Information about Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.Passage 1 is adapted from Radhika Singh, “Mice Utopias and the Behavioral Sink," published July 31, 2015 in the blog of The Borgen Project (borgenproject. org). Passage 2 is adapted from Frans de Waal, “Is it Behavioral Sink or Resource Distribution?" published in Scientific American online July 21, 2010.Passage 1In 1972, behavioral researcher John Calhounintroduced four breeding pairs of mice into a box9-feet square and 4.5-feet high. It was a “perfect(5) universe:” the mice were safe from predators anddisease and given ample food and water. Theydoubled in population every 55 days.However, within a year males stoppeddefending their territory, random violence broke(10) out, and female mice attacked their own offspring.Normal social bonds and interactions completelybroke down. Infant abandonment soared, andmortality climbed. Cannibalism appeared, eventhough there was more than enough food. Fertile(15) females closed themselves off from society, andmales of reproductive age—Calhoun called themthe “beautiful ones”—did nothing but eat, sleepand groom.Calhoun called this breakdown the(20) “behavioral sink,” vand believed it came aboutwhen there were too many mice and a lack ofimportant social roles for each one to play. Evenwhen enough of the population died off so thatonly an optimal population remained, the mice(25) were not able to return to their natural behavior.This connection between a breakdown ofsocial bonds and violence was observed by EmileDurkheim in the late 19th century. In traditionalsocieties, where family expectations and religion(30) held sway, people enjoyed strong social bondsand had distinct social roles to fill. However,as they moved to cities, they found they werefighting for a place in society. In exasperation anda state of helplessness, many fell into poverty or(35) turned to crime, violence and even suicide.The fear of failing to be a productive memberof society and fulfilling social roles can also pushpeople, like the “beautiful ones,” into isolatingthemselves. For instance, Japanese “hikikomori”(40) refuse to leave their rooms, sometimes for years,because they feel shame for being unable to fulfillfamilial expectations.However, it is not clear that a high populationdensity necessarily leads to a breakdown of(45) society and social roles. Humans might beable, with our ingenuity, to create social rolesfor everyone and avoid the behavioral sink.Some critics, such as psychologist JonathanFreedam, suggested that it was not the density of(50) population that overwhelmed the mice but thelarge number of social interactions they had todeal with. Humans are able to avoid this, evenwhile living in a highly dense area.Passage 2In the 1960s, John Calhoun placed a group(55) of rats in a room and observed how the animalskilled, sexually assaulted and, eventually,cannibalized one another. Thisbehavioral deviancy led Calhoun to coin the phrase“behavioral sink.”(60) In no time, popularizers were comparingpolitically motivated street riots with rat packsand inner cities to behavioral sinks. Warningthat society was heading for either anarchy ordictatorship, Robert Ardrey, a popular science(65) journalist, remarked in 1970 on the voluntarynature of human crowding and its ill effects. Thenegative impact of crowding became a centraltenet of the voluminous literature on aggression.In extrapolating from rodents to people,(70) however, these writers were making a giant leap.Compare, for instance, the per capita murderrates with the number of people per squarekilometer in different nations. There is in fact nostatistically meaningful relation. Among free-(75) market nations, the U.S. has the highest homiciderate despite a low population density.To see how other primates respond to beingpacked together, we compared rhesus monkeysin crowded cages with those roaming free(80) on Morgan Island in South Carolina. We alsocompared chimpanzees in indoor enclosureswith those living on large forested islands.Nothing like the expected crowding effectscould be found. If anything, primates become(85) more sociable in captivity, grooming each othermore—probably in an effort to counter thepotential of conflict, which is greater the closerthey live together. Primates are excellent atconflict resolution.(90) For the future of the world this means thatcrowding by itself is perhaps not the problem itis made it out to be. Resource distribution seemsthe real issue. This was already true for Calhounsrats, the violence among them could be explained(95) by concentrated food sources and competition.Also for humans, I would worry more aboutsustainability and resource distribution thanpopulation density.Phase A: Days 1–104 (Social Adjustment): Mice are introduced (4 males and 4 females). Nests are established.Phase B: Days 105–315 (Rapid growth): Population doubles every 55 days.Male strength corresponds to frequency of reproduction. As crowding develops, immature males begin to proliferate within the population.Phase C: Days 316–560 (Stagnation): Population doubles every 145 days.Male ability to defend territory declines. Nursing females become more aggressive, even towards own offspring. By midway point in Phase C, virtually all young are prematurely rejected by their mothers. Although 20% of nest sites are unoccupied, there is severe overcrowding in other sites.Withdrawn males become more violent toward each other.Phase D: Days 561–1588 (Death): Population begins to decline on Day 561.Incidences of pregnancy decline rapidly with no young surviving. The last 1000 mice born grow up with no social skills or ability to defend territory. The males become withdrawn and obsessed with their own grooming.Q.As used in line 2, “introduced” most nearly meansa)pioneered.b)acquainted.c)inserted.d)announced.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for SAT 2025 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.Passage 1 is adapted from Radhika Singh, “Mice Utopias and the Behavioral Sink," published July 31, 2015 in the blog of The Borgen Project (borgenproject. org). Passage 2 is adapted from Frans de Waal, “Is it Behavioral Sink or Resource Distribution?" published in Scientific American online July 21, 2010.Passage 1In 1972, behavioral researcher John Calhounintroduced four breeding pairs of mice into a box9-feet square and 4.5-feet high. It was a “perfect(5) universe:” the mice were safe from predators anddisease and given ample food and water. Theydoubled in population every 55 days.However, within a year males stoppeddefending their territory, random violence broke(10) out, and female mice attacked their own offspring.Normal social bonds and interactions completelybroke down. Infant abandonment soared, andmortality climbed. Cannibalism appeared, eventhough there was more than enough food. Fertile(15) females closed themselves off from society, andmales of reproductive age—Calhoun called themthe “beautiful ones”—did nothing but eat, sleepand groom.Calhoun called this breakdown the(20) “behavioral sink,” vand believed it came aboutwhen there were too many mice and a lack ofimportant social roles for each one to play. Evenwhen enough of the population died off so thatonly an optimal population remained, the mice(25) were not able to return to their natural behavior.This connection between a breakdown ofsocial bonds and violence was observed by EmileDurkheim in the late 19th century. In traditionalsocieties, where family expectations and religion(30) held sway, people enjoyed strong social bondsand had distinct social roles to fill. However,as they moved to cities, they found they werefighting for a place in society. In exasperation anda state of helplessness, many fell into poverty or(35) turned to crime, violence and even suicide.The fear of failing to be a productive memberof society and fulfilling social roles can also pushpeople, like the “beautiful ones,” into isolatingthemselves. For instance, Japanese “hikikomori”(40) refuse to leave their rooms, sometimes for years,because they feel shame for being unable to fulfillfamilial expectations.However, it is not clear that a high populationdensity necessarily leads to a breakdown of(45) society and social roles. Humans might beable, with our ingenuity, to create social rolesfor everyone and avoid the behavioral sink.Some critics, such as psychologist JonathanFreedam, suggested that it was not the density of(50) population that overwhelmed the mice but thelarge number of social interactions they had todeal with. Humans are able to avoid this, evenwhile living in a highly dense area.Passage 2In the 1960s, John Calhoun placed a group(55) of rats in a room and observed how the animalskilled, sexually assaulted and, eventually,cannibalized one another. Thisbehavioral deviancy led Calhoun to coin the phrase“behavioral sink.”(60) In no time, popularizers were comparingpolitically motivated street riots with rat packsand inner cities to behavioral sinks. Warningthat society was heading for either anarchy ordictatorship, Robert Ardrey, a popular science(65) journalist, remarked in 1970 on the voluntarynature of human crowding and its ill effects. Thenegative impact of crowding became a centraltenet of the voluminous literature on aggression.In extrapolating from rodents to people,(70) however, these writers were making a giant leap.Compare, for instance, the per capita murderrates with the number of people per squarekilometer in different nations. There is in fact nostatistically meaningful relation. Among free-(75) market nations, the U.S. has the highest homiciderate despite a low population density.To see how other primates respond to beingpacked together, we compared rhesus monkeysin crowded cages with those roaming free(80) on Morgan Island in South Carolina. We alsocompared chimpanzees in indoor enclosureswith those living on large forested islands.Nothing like the expected crowding effectscould be found. If anything, primates become(85) more sociable in captivity, grooming each othermore—probably in an effort to counter thepotential of conflict, which is greater the closerthey live together. Primates are excellent atconflict resolution.(90) For the future of the world this means thatcrowding by itself is perhaps not the problem itis made it out to be. Resource distribution seemsthe real issue. This was already true for Calhounsrats, the violence among them could be explained(95) by concentrated food sources and competition.Also for humans, I would worry more aboutsustainability and resource distribution thanpopulation density.Phase A: Days 1–104 (Social Adjustment): Mice are introduced (4 males and 4 females). Nests are established.Phase B: Days 105–315 (Rapid growth): Population doubles every 55 days.Male strength corresponds to frequency of reproduction. As crowding develops, immature males begin to proliferate within the population.Phase C: Days 316–560 (Stagnation): Population doubles every 145 days.Male ability to defend territory declines. Nursing females become more aggressive, even towards own offspring. By midway point in Phase C, virtually all young are prematurely rejected by their mothers. Although 20% of nest sites are unoccupied, there is severe overcrowding in other sites.Withdrawn males become more violent toward each other.Phase D: Days 561–1588 (Death): Population begins to decline on Day 561.Incidences of pregnancy decline rapidly with no young surviving. The last 1000 mice born grow up with no social skills or ability to defend territory. The males become withdrawn and obsessed with their own grooming.Q.As used in line 2, “introduced” most nearly meansa)pioneered.b)acquainted.c)inserted.d)announced.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer?.

Solutions for Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.Passage 1 is adapted from Radhika Singh, “Mice Utopias and the Behavioral Sink," published July 31, 2015 in the blog of The Borgen Project (borgenproject. org). Passage 2 is adapted from Frans de Waal, “Is it Behavioral Sink or Resource Distribution?" published in Scientific American online July 21, 2010.Passage 1In 1972, behavioral researcher John Calhounintroduced four breeding pairs of mice into a box9-feet square and 4.5-feet high. It was a “perfect(5) universe:” the mice were safe from predators anddisease and given ample food and water. Theydoubled in population every 55 days.However, within a year males stoppeddefending their territory, random violence broke(10) out, and female mice attacked their own offspring.Normal social bonds and interactions completelybroke down. Infant abandonment soared, andmortality climbed. Cannibalism appeared, eventhough there was more than enough food. Fertile(15) females closed themselves off from society, andmales of reproductive age—Calhoun called themthe “beautiful ones”—did nothing but eat, sleepand groom.Calhoun called this breakdown the(20) “behavioral sink,” vand believed it came aboutwhen there were too many mice and a lack ofimportant social roles for each one to play. Evenwhen enough of the population died off so thatonly an optimal population remained, the mice(25) were not able to return to their natural behavior.This connection between a breakdown ofsocial bonds and violence was observed by EmileDurkheim in the late 19th century. In traditionalsocieties, where family expectations and religion(30) held sway, people enjoyed strong social bondsand had distinct social roles to fill. However,as they moved to cities, they found they werefighting for a place in society. In exasperation anda state of helplessness, many fell into poverty or(35) turned to crime, violence and even suicide.The fear of failing to be a productive memberof society and fulfilling social roles can also pushpeople, like the “beautiful ones,” into isolatingthemselves. For instance, Japanese “hikikomori”(40) refuse to leave their rooms, sometimes for years,because they feel shame for being unable to fulfillfamilial expectations.However, it is not clear that a high populationdensity necessarily leads to a breakdown of(45) society and social roles. Humans might beable, with our ingenuity, to create social rolesfor everyone and avoid the behavioral sink.Some critics, such as psychologist JonathanFreedam, suggested that it was not the density of(50) population that overwhelmed the mice but thelarge number of social interactions they had todeal with. Humans are able to avoid this, evenwhile living in a highly dense area.Passage 2In the 1960s, John Calhoun placed a group(55) of rats in a room and observed how the animalskilled, sexually assaulted and, eventually,cannibalized one another. Thisbehavioral deviancy led Calhoun to coin the phrase“behavioral sink.”(60) In no time, popularizers were comparingpolitically motivated street riots with rat packsand inner cities to behavioral sinks. Warningthat society was heading for either anarchy ordictatorship, Robert Ardrey, a popular science(65) journalist, remarked in 1970 on the voluntarynature of human crowding and its ill effects. Thenegative impact of crowding became a centraltenet of the voluminous literature on aggression.In extrapolating from rodents to people,(70) however, these writers were making a giant leap.Compare, for instance, the per capita murderrates with the number of people per squarekilometer in different nations. There is in fact nostatistically meaningful relation. Among free-(75) market nations, the U.S. has the highest homiciderate despite a low population density.To see how other primates respond to beingpacked together, we compared rhesus monkeysin crowded cages with those roaming free(80) on Morgan Island in South Carolina. We alsocompared chimpanzees in indoor enclosureswith those living on large forested islands.Nothing like the expected crowding effectscould be found. If anything, primates become(85) more sociable in captivity, grooming each othermore—probably in an effort to counter thepotential of conflict, which is greater the closerthey live together. Primates are excellent atconflict resolution.(90) For the future of the world this means thatcrowding by itself is perhaps not the problem itis made it out to be. Resource distribution seemsthe real issue. This was already true for Calhounsrats, the violence among them could be explained(95) by concentrated food sources and competition.Also for humans, I would worry more aboutsustainability and resource distribution thanpopulation density.Phase A: Days 1–104 (Social Adjustment): Mice are introduced (4 males and 4 females). Nests are established.Phase B: Days 105–315 (Rapid growth): Population doubles every 55 days.Male strength corresponds to frequency of reproduction. As crowding develops, immature males begin to proliferate within the population.Phase C: Days 316–560 (Stagnation): Population doubles every 145 days.Male ability to defend territory declines. Nursing females become more aggressive, even towards own offspring. By midway point in Phase C, virtually all young are prematurely rejected by their mothers. Although 20% of nest sites are unoccupied, there is severe overcrowding in other sites.Withdrawn males become more violent toward each other.Phase D: Days 561–1588 (Death): Population begins to decline on Day 561.Incidences of pregnancy decline rapidly with no young surviving. The last 1000 mice born grow up with no social skills or ability to defend territory. The males become withdrawn and obsessed with their own grooming.Q.As used in line 2, “introduced” most nearly meansa)pioneered.b)acquainted.c)inserted.d)announced.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? in English & in Hindi are available as part of our courses for SAT.

Download more important topics, notes, lectures and mock test series for SAT Exam by signing up for free.

Here you can find the meaning of Question based on the following passages and supplementary material.Passage 1 is adapted from Radhika Singh, “Mice Utopias and the Behavioral Sink," published July 31, 2015 in the blog of The Borgen Project (borgenproject. org). Passage 2 is adapted from Frans de Waal, “Is it Behavioral Sink or Resource Distribution?" published in Scientific American online July 21, 2010.Passage 1In 1972, behavioral researcher John Calhounintroduced four breeding pairs of mice into a box9-feet square and 4.5-feet high. It was a “perfect(5) universe:” the mice were safe from predators anddisease and given ample food and water. Theydoubled in population every 55 days.However, within a year males stoppeddefending their territory, random violence broke(10) out, and female mice attacked their own offspring.Normal social bonds and interactions completelybroke down. Infant abandonment soared, andmortality climbed. Cannibalism appeared, eventhough there was more than enough food. Fertile(15) females closed themselves off from society, andmales of reproductive age—Calhoun called themthe “beautiful ones”—did nothing but eat, sleepand groom.Calhoun called this breakdown the(20) “behavioral sink,” vand believed it came aboutwhen there were too many mice and a lack ofimportant social roles for each one to play. Evenwhen enough of the population died off so thatonly an optimal population remained, the mice(25) were not able to return to their natural behavior.This connection between a breakdown ofsocial bonds and violence was observed by EmileDurkheim in the late 19th century. In traditionalsocieties, where family expectations and religion(30) held sway, people enjoyed strong social bondsand had distinct social roles to fill. However,as they moved to cities, they found they werefighting for a place in society. In exasperation anda state of helplessness, many fell into poverty or(35) turned to crime, violence and even suicide.The fear of failing to be a productive memberof society and fulfilling social roles can also pushpeople, like the “beautiful ones,” into isolatingthemselves. For instance, Japanese “hikikomori”(40) refuse to leave their rooms, sometimes for years,because they feel shame for being unable to fulfillfamilial expectations.However, it is not clear that a high populationdensity necessarily leads to a breakdown of(45) society and social roles. Humans might beable, with our ingenuity, to create social rolesfor everyone and avoid the behavioral sink.Some critics, such as psychologist JonathanFreedam, suggested that it was not the density of(50) population that overwhelmed the mice but thelarge number of social interactions they had todeal with. Humans are able to avoid this, evenwhile living in a highly dense area.Passage 2In the 1960s, John Calhoun placed a group(55) of rats in a room and observed how the animalskilled, sexually assaulted and, eventually,cannibalized one another. Thisbehavioral deviancy led Calhoun to coin the phrase“behavioral sink.”(60) In no time, popularizers were comparingpolitically motivated street riots with rat packsand inner cities to behavioral sinks. Warningthat society was heading for either anarchy ordictatorship, Robert Ardrey, a popular science(65) journalist, remarked in 1970 on the voluntarynature of human crowding and its ill effects. Thenegative impact of crowding became a centraltenet of the voluminous literature on aggression.In extrapolating from rodents to people,(70) however, these writers were making a giant leap.Compare, for instance, the per capita murderrates with the number of people per squarekilometer in different nations. There is in fact nostatistically meaningful relation. Among free-(75) market nations, the U.S. has the highest homiciderate despite a low population density.To see how other primates respond to beingpacked together, we compared rhesus monkeysin crowded cages with those roaming free(80) on Morgan Island in South Carolina. We alsocompared chimpanzees in indoor enclosureswith those living on large forested islands.Nothing like the expected crowding effectscould be found. If anything, primates become(85) more sociable in captivity, grooming each othermore—probably in an effort to counter thepotential of conflict, which is greater the closerthey live together. Primates are excellent atconflict resolution.(90) For the future of the world this means thatcrowding by itself is perhaps not the problem itis made it out to be. Resource distribution seemsthe real issue. This was already true for Calhounsrats, the violence among them could be explained(95) by concentrated food sources and competition.Also for humans, I would worry more aboutsustainability and resource distribution thanpopulation density.Phase A: Days 1–104 (Social Adjustment): Mice are introduced (4 males and 4 females). Nests are established.Phase B: Days 105–315 (Rapid growth): Population doubles every 55 days.Male strength corresponds to frequency of reproduction. As crowding develops, immature males begin to proliferate within the population.Phase C: Days 316–560 (Stagnation): Population doubles every 145 days.Male ability to defend territory declines. Nursing females become more aggressive, even towards own offspring. By midway point in Phase C, virtually all young are prematurely rejected by their mothers. Although 20% of nest sites are unoccupied, there is severe overcrowding in other sites.Withdrawn males become more violent toward each other.Phase D: Days 561–1588 (Death): Population begins to decline on Day 561.Incidences of pregnancy decline rapidly with no young surviving. The last 1000 mice born grow up with no social skills or ability to defend territory. The males become withdrawn and obsessed with their own grooming.Q.As used in line 2, “introduced” most nearly meansa)pioneered.b)acquainted.c)inserted.d)announced.Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? defined & explained in the simplest way possible. Besides giving the explanation of